Southern Min

| Southern Min | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hokkien-Taiwanese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

閩南語 / 闽南语 河洛話 / 福老話 Hō-ló-oē / Hô-ló-uē | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Koa-a books, Minnan written in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native to | China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and other areas of Southern Min and Hoklo settlement | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Region | Fujian province; the Chaozhou-Shantou (Chaoshan) area and Leizhou Peninsula in Guangdong province; extreme south of Zhejiang province; much of Hainan province (if Hainanese or Qiongwen is included); and most of Taiwan. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnicity |

Hoklo people Teochew people Hainanese people | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Native speakers | 47 million (2007)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dialects | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese characters; Latin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official status | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Official language in | None; one of the statutory languages for public transport announcements in Taiwan[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regulated by | None (The Republic of China Ministry of Education and some NGOs are influential in Taiwan) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language codes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 639-3 |

nan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glottolog |

minn1241[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Linguasphere |

79-AAA-j | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

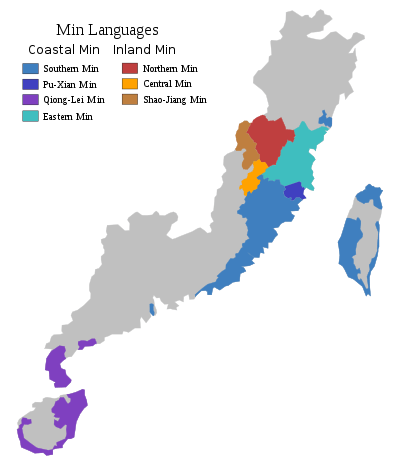

Southern Min in China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Subgroups of Southern Min in China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 闽南语 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 閩南語 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Language of Southern Min [Fujian]" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Southern Min, or Minnan (simplified Chinese: 闽南语; traditional Chinese: 閩南語), is a branch of Min Chinese spoken in Taiwan and in certain parts of China including Fujian (especially the Minnan region), eastern Guangdong, Hainan, and southern Zhejiang.[4] The Minnan dialects are also spoken by descendants of emigrants from these areas in diaspora, most notably the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. It is the largest Min Chinese branch and the most widely distributed Min Chinese subgroup.

In common parlance and in the narrower sense, Southern Min refers to the Quanzhang or Hokkien-Taiwanese variety of Southern Min originating from Southern Fujian in Mainland China. It is spoken mainly in Fujian, Taiwan, as well as certain parts of Southeast Asia. The Quanzhang variety is often called simply "Minnan Proper" (simplified Chinese: 闽南语; traditional Chinese: 閩南語). It is considered the de-facto mainstream form of Southern Min.

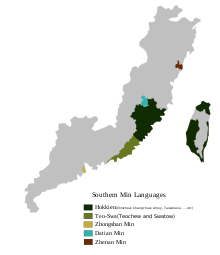

In the wider scope, Southern Min also includes other Min Chinese varieties that are linguistically related to Minnan proper (Quanzhang). Most variants of Southern Min have significant differences from the Quanzhang variety, some having limited mutual intelligibility with it, others almost none. Teochew, Longyan, and Zhenan may be said to have limited mutual intelligibility with Minnan Proper, sharing similar phonology and vocabulary to a small extent. On the other hand, variants such as Datian, Zhongshan, and Qiong-Lei have historical linguistic roots with Minnan Proper, but are significantly divergent from it in terms of phonology and vocabulary, and thus have almost no mutual intelligibility with the Quanzhang variety. Linguists tend to classify them as separate Min languages.

Southern Min is not mutually intelligible with other branches of Min Chinese nor other varieties of Chinese, such as Mandarin.

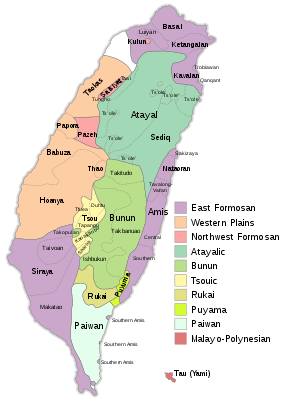

Geographic distribution

China

Southern Min dialects are spoken in Fujian, three southeastern counties of Zhejiang, the Zhoushan archipelago off Ningbo in Zhejiang, and the Chaoshan (Teo-swa) region in Guangdong. The variant spoken in Leizhou, Guangdong as well as Hainan is Hainanese and is not mutually intelligible with mainstream Southern Min or Teochew. Hainanese is classified in some schemes as part of Southern Min and in other schemes as separate. Puxian Min was originally based on the Quanzhou dialect, but over time became heavily influenced by Eastern Min, eventually losing intelligibility with Minnan.The Southern Min dialects spoken in Taiwan, collectively known as Taiwanese, Southern Min is a first language for most of the Hoklo people, the main ethnicity of Taiwan. The correspondence between language and ethnicity is not absolute, as some Hoklo have very limited proficiency in Southern Min while some non-Hoklo speak Southern Min fluently.

Southeast Asia

There are many Southern Min speakers among Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. Many ethnic Chinese immigrants to the region were Hoklo from southern Fujian and brought the language to what is now Burma, Indonesia (the former Dutch East Indies) and present-day Malaysia and Singapore (formerly British Malaya and the Straits Settlements). In general, Southern Min from southern Fujian is known as Hokkien, Hokkienese, Fukien or Fookien in Southeast Asia and is mostly mutually intelligible with Hokkien spoken elsewhere. Many Southeast Asian ethnic Chinese also originated in the Chaoshan region of Guangdong and speak Teochew language, the variant of Southern Min from that region. Philippine Hokkien is reportedly the native language of up to 98.5% of the Chinese Filipino community in the Philippines, among whom it is also known as Lan-nang or Lán-lâng-oē ("our people’s language")or 蘭人話 most likely this is during the Spanish colonial era when all Chinese are restricted within a district with ‘fencing’ and during the warring period 300bc uses this term as a separation between the local and outsider, although Hoklo people consist of only around 60% of the Chinese Filipino population.

Southern Min speakers form the majority of Chinese in Singapore, with the largest group being Minnan Proper (Hokkien-Taiwanese) and the second largest being Teochew. Despite the similarities, the two groups are rarely seen as part of the same "Minnan" Chinese subgroups.

Classification

The variants of Southern Min spoken in Zhejiang province are most akin to that spoken in Quanzhou. The variants spoken in Taiwan are similar to the three Fujian variants and are collectively known as Taiwanese.

Those Southern Min variants that are collectively known as "Hokkien" in Southeast Asia also originate from these variants. The variants of Southern Min in the Chaoshan region of eastern Guangdong province are collectively known as Teochew or Chaozhou. Teochew is of great importance in the Southeast Asian Chinese diaspora, particularly in Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Sumatra and West Kalimantan. The Philippines variant is mostly from the Quanzhou area as most of their forefathers are from the aforementioned area.

The Southern Min language variant spoken around Shanwei and Haifeng differs markedly from Teochew and may represent a later migration from Zhangzhou. Linguistically, it lies between Teochew and Amoy. In southwestern Fujian, the local variants in Longyan and Zhangping form a separate division of Minnan on their own. Among ethnic Chinese inhabitants of Penang, Malaysia and Medan, Indonesia, a distinct form based on the Zhangzhou dialect has developed. In Penang, it is called Penang Hokkien while across the Malacca Strait in Medan, an almost identical variant is known as Medan Hokkien.

Varieties

There are three major divisions of Southern Min :

- Minnan Proper (Hokkien–Taiwanese) under the Quanzhang division (泉漳片)

- Teochew under the Chaoshan division (潮汕片)

- Leizhou and Hainanese dialects under the Qiong-Lei division (琼雷片).

Quanzhang

The group of mutually intelligible Quanzhang (泉漳片) dialects, spoken around the areas of Xiamen, Quanzhou and Zhangzhou in Southern Fujian are collectively called Minnan Proper (闽南语/闽南话) or Hokkien-Taiwanese, is the mainstream form of Southern Min. It is also the widely spoken non-official regional language in Taiwan. There are two types of standard Minnan. They are classified as Traditional Standard Minnan and Modern Standard Minnan. The Traditional Standard Minnan is based on Quanzhou dialect spoken in Quanzhou, it is the dialect used in Liyuan Opera (梨园戏) and Nanying music (南音). The Modern standard forms of Minnan Proper is based on Amoy dialect spoken in the city of Xiamen and Taiwanese dialect spoken around the city of Tainan in Taiwan. Both Modern Standard forms of Minnan are a combination of Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speeches. Nowadays, Modern Standard Minnan is the dialect of minnan that is popular in Minnan dialect television programming, radio programming and Minnan songs. Most Minnan language books and Minnan dictionaries are mostly based on the pronunciation of the Modern Standard Minnan. Taiwanese in northern Taiwan tends to be based on Quanzhou dialect, whereas the Taiwanese spoken in southern Taiwan tends to be based on Zhangzhou dialect. There are minor variations in pronunciation and vocabulary between Quanzhou and Zhangzhou speech. The grammar is basically the same. Additionally, in Taiwanese Minnan, extensive contact with the Japanese language has left a legacy of Japanese loanwords.

Teo-Swa

Teochew, or Chaoshan speech (潮汕片), is a closely related variant of Minnan that includes Swatow dialect. It has limited mutual intelligibility with Quanzhang speech though they share some cognates with each other. Teochew speech is significantly different from Quanzhang speech in both pronunciation and vocabulary. It had its origins from Proto-Putian dialect (闽南语古莆田话), a sub-dialect of Proto Minnan - which is closely related to Quanzhou dialect. As the Proto-Putian dialect speaking Chinese emigrants from Putian perfecture settled on Chaoshan region, it later received influence from Zhangzhou dialect. It follows the same grammar pattern as Minnan Proper. It is marginally understood by Minnan Proper speakers to a small degree.[5]

Qiong-Lei

Qiong-Lei speech (琼雷片), is a distantly related variant of Minnan which is spoken in the Leizhou peninsula and the southern Chinese island province of Hainan. The Qiong-Lei variant of Minnan shares historical linguistic roots with Minnan Proper. However, it developed into a distinctive language of its own due to the fact that these variants are spoken in the geographic location that is relatively distant from the Southern Min region. Over time, these dialects evolved into a distinct language of its own which featured drastic changes to initial consonants, including a series of implosive consonants, that have been attributed to contact with the aboriginal languages such as Tai-Kadai languages. As a result, it has lost much of its mutual intelligibility with mainstream Minnan (Hokkien-Taiwanese). It is not understood well by speakers of mainstream Minnan. Since the late 20th century, many linguists consider this Southern Min variant as a separate Min language.

Phonology

Southern Min has one of the most diverse phonologies of Chinese varieties, with more consonants than Mandarin or Cantonese. Vowels, on the other hand, are more-or-less similar to those of Mandarin. In general, Southern Min dialects have five to six tones, and tone sandhi is extensive. There are minor variations within Hokkien, and the Teochew system differs somewhat more.

Southern Min's nasal finals consist m, n, ŋ, ~.

Writing systems

Southern Min dialects lack a standardized written language. Southern Min speakers are taught how to read Standard Chinese in school. As a result, there has not been an urgent need to develop a writing system. In recent years, an increasing number of Southern Min speakers have become interested in developing a standard writing system (either by using Chinese Characters, or using Romanized script).

History

The Min homeland of Fujian was opened to Chinese settlement by the defeat of the Minyue state by the armies of Emperor Wu of Han in 110 BC.[6] The area features rugged mountainous terrain, with short rivers that flow into the South China Sea. Most subsequent migration from north to south China passed through the valleys of the Xiang and Gan rivers to the west, so that Min varieties have experienced less northern influence than other southern groups.[7] As a result, whereas most varieties of Chinese can be treated as derived from Middle Chinese, the language described by rhyme dictionaries such as the Qieyun (601 AD), Min varieties contain traces of older distinctions.[8] Linguists estimate that the oldest layers of Min dialects diverged from the rest of Chinese around the time of the Han dynasty.[9][10] However, significant waves of migration from the North China Plain occurred:[11]

- The Uprising of the Five Barbarians during the Jin dynasty, particularly the Disaster of Yongjia in 311 AD, caused a tide of immigration to the south.

- In 669, Chen Zheng and his son Chen Yuanguang from Gushi County in Henan set up a regional administration in Fujian to suppress an insurrection by the She people.

- Wang Chao was appointed governor of Fujian in 893, near the end of the Tang dynasty, and brought tens of thousands of troops from Henan. In 909, following the fall of the Tang dynasty, his son Wang Shenzhi founded the Min Kingdom, one of the Ten Kingdoms in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Jerry Norman identifies four main layers in the vocabulary of modern Min varieties:

- A non-Chinese substratum from the original languages of Minyue, which Norman and Mei Tsu-lin believe were Austroasiatic.[12][13]

- The earliest Chinese layer, brought to Fujian by settlers from Zhejiang to the north during the Han dynasty.[14]

- A layer from the Northern and Southern Dynasties period, which is largely consistent with the phonology of the Qieyun dictionary.[15]

- A literary layer based on the koiné of Chang'an, the capital of the Tang dynasty.[16]

Comparisons with Sino-Xenic character pronunciations

Minnan (or Hokkien) can trace its origins through the Tang Dynasty, and it also has roots from earlier periods. Minnan (Hokkien) people call themselves "Tang people", (唐人, pronounced as "唐儂" Thn̂g-lâng) which is synonymous to "Chinese people". Because of the widespread influence of the Tang culture during the great Tang dynasty, there are today still many Minnan pronunciations of words shared by the Sino-xenic pronunciations of Vietnamese, Korean and Japanese languages.

| English | Han characters | Mandarin Chinese | Taiwanese Minnan[17] | Teochew | Cantonese | Korean | Vietnamese | Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Book | 冊 | Cè | Chhek/Chheh | ze1 | caak3 | Chaek (책) | Tập/Sách | Saku/Satsu/Shaku |

| Bridge | 橋 | Qiáo | Kiâu/Kiô | giê5 | kiu4 | Gyo (교) | Cầu/Kiều | Kyō |

| Dangerous | 危險 | Wēixiǎn | Guî-hiám | guîn5/nguín5 hiem2 | ngai4 him2 | Wiheom (위험) | Nguy hiểm | Kiken |

| Embassy | 大使館 | Dàshǐguǎn | Tāi-sài-koán | dai6 sái2 guêng2 | daai6 si3 gun2 | Daesagwan (대사관) | Đại Sứ Quán | Taishikan |

| Flag | 旗 | Qí | Kî | kî5 | kei4 | Gi (기) | Cờ/Kỳ | Ki |

| Insurance | 保險 | Bǎoxiǎn | Pó-hiám | Bó2-hiém | bou2 him2 | Boheom (보험) | Bảo hiểm | Hoken |

| News | 新聞 | Xīnwén | Sin-bûn | sing1 bhung6 | san1 man4 | Shinmun (신문) | Tân Văn | Shinbun |

| Student | 學生 | Xuéshēng | Ha̍k-seng | Hak8 sêng1 | hok6 saang1 | Haksaeng (학생) | Học sinh | Gakusei |

| University | 大學 | Dàxué | Tāi-ha̍k/Tōa-o̍h | dai6 hag8/dua7 oh8 | daai6 hok6 | Daehak (대학) | Đại học | Daigaku |

See also

Related languages

- Fuzhou dialect (Min Dong branch)

- Lan-nang (Philippine dialect of Minnan)

- Medan Hokkien (North-Sumatra, Indonesia dialect of Minnan)

- Penang Hokkien

- Singaporean Hokkien

- Southern Malaysia Hokkien

- Taiwanese Minnan

References

- ↑ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ↑ 大眾運輸工具播音語言平等保障法

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Minnan Chinese". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ CAI ZHU, HUANG GUO (1 October 2015). Chinese language. Xiamen: Fujian Education Publishing House. ISBN 7533469518.

- ↑ Minnan/ Southern Min at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Norman (1991), pp. 328.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 210, 228.

- ↑ Norman (1988), pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Ting (1983), pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Baxter & Sagart (2014), pp. 33, 79.

- ↑ Yan (2006), p. 120.

- ↑ Norman & Mei (1976).

- ↑ Norman (1991), pp. 331–332.

- ↑ Norman (1991), pp. 334–336.

- ↑ Norman (1991), p. 336.

- ↑ Norman (1991), p. 337.

- ↑ Iûⁿ, Ún-giân. "Tâi-bûn/Hôa-bûn Sòaⁿ-téng Sû-tián" 台文/華文線頂辭典 [Taiwanese/Chinese Online Dictionary]. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

Further reading

- Branner, David Prager (2000). Problems in Comparative Chinese Dialectology — the Classification of Miin and Hakka. Trends in Linguistics series, no. 123. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015831-0.

- Chung, Raung-fu (1996). The segmental phonology of Southern Min in Taiwan. Taipei: Crane Pub. Co. ISBN 957-9463-46-8.

- DeBernardi, Jean (1991). "Linguistic nationalism: the case of Southern Min". Sino-Platonic Papers. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. 25. OCLC 24810816.

- Chappell, Hilary, ed. (2001). Sinitic Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-829977-X. "Part V: Southern Min Grammar" (3 articles).

External links

| Min Nan Chinese edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Southern Min test of Wikibooks at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Minnan |

| Look up Minnan in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Minnan phrasebook. |

- Amoy Minnan Swadesh list (Wiktionary)

- Appendix:Sino-Tibetan Swadesh lists (Wiktionary)

- 當代泉州音字彙, a dictionary of Quanzhou speech

- Iûⁿ, Ún-giân (2006). "Tai-gi Hôa-gí Sòaⁿ-téng Sû-tián" 台文/華文線頂辭典 [On-line Taiwanese/Mandarin Dictionary] (in Chinese and Min Nan Chinese). .

- Iûⁿ, Ún-giân. 台語線頂字典 [Taiwanese Hokkien Online Character Dictionary] (in Taiwanese and Chinese).

- 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典, Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan by Ministry of Education, Republic of China (Taiwan).

- 臺灣本土語言互譯及語音合成系統, Taiwanese-Hakka-Mandarin on-line conversion

- Voyager - Spacecraft - Golden Record - Greetings From Earth - Amoy The voyager clip says: Thài-khong pêng-iú, lín-hó. Lín chia̍h-pá--bē? Ū-êng, to̍h lâi gún chia chē--ô·! 太空朋友,恁好。恁食飽未?有閒著來阮遮坐哦!

- 台語詞典 Taiwanese-English-Mandarin Dictionary

- How to Forget Your Mother Tongue and Remember Your National Language by Victor H. Mair University of Pennsylvania

- ISO 639-3 change request 2008-083, requesting to replace code nan (Minnan Chinese) with dzu (Chaozhou) and xim (Xiamen), rejected because it did not include codes to cover the rest of the group.