Amoy dialect

| Amoy/Xiamen | |

|---|---|

| Amoynese, Xiamenese | |

| 廈門話 Ē-mn̂g-ōe | |

| Native to | China, Taiwan, Japan (due to large Taiwanese communities in the Greater Tokyo and Greater Osaka areas), Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Philippines, as well as other overseas settlements of Hoklo people |

| Region | City of Xiamen (Amoy) and its surrounding metropolitan area. |

Native speakers | over 10 million (no recent data) |

|

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog |

xiam1236[1] |

| Linguasphere |

79-AAA-je > 79-AAA-jeb |

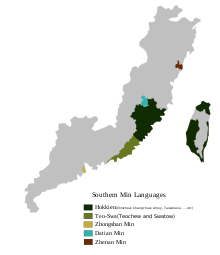

Distribution of Hokkien dialects. Amoy dialect is in magenta. | |

The Amoy dialect or Xiamen dialect (Chinese: 廈門話; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Ē-mn̂g-ōe), also known as Amoynese, Amoy Hokkien, Xiamenese or Xiamen Hokkien, is a dialect of Hokkien spoken in the city of Xiamen (historically known as "Amoy") and its surrounding metropolitan area, in the southern part of Fujian province. Currently, it is one of the most widely researched and studied varieties of Southern Min.[2] It has historically come to be one of the more standardized varieties.[3] Most present-day publications in Southern Min are mostly based on this dialect.

Spoken Amoynese and Taiwanese are both mixtures of the Quanzhou and Zhangzhou spoken dialects.[4] As such, they are very closely aligned phonologically. However, there are some subtle differences between the two, as a result of physical separation and other historical factors. The lexical differences between the two are slightly more pronounced. Generally speaking, the Southern Min dialects spoken in Xiamen, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Taiwan, Southeast Asia and Overseas Communities are mutually intelligible, with only slight differences.[5]

History

In 1842, as a result of the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, Amoy was designated as a trading port in Fujian. Amoy and Kulangsu rapidly developed, which resulted in a large influx of people from neighboring areas such as Quanzhou and Zhangzhou. The mixture of these various accents formed the basis for the Amoy dialect.

Over the last several centuries, a large number of Fujianese peoples from these same areas migrated to Taiwan during Dutch rule and Qing rule. Eventually, the mixture of accents spoken in Taiwan became popularly known as Taiwanese during Imperial Japanese rule. As in American and British English, there are subtle lexical and phonological differences between modern Taiwanese and Amoy Hokkien; however, these differences do not generally pose any barriers to communication. Amoy dialect speakers also migrated to Southeast Asia, mainly in the Philippines (where it is known as Lan-nang), Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

Special characteristics

Spoken Amoy dialect preserves many of the sounds and words from Old Chinese. However, the vocabulary of Amoy was also influenced in its early stages by the languages of the ancient Minyue peoples.[6] Spoken Amoy is known for its extensive use of nasalization.

Unlike Mandarin, Amoy dialect distinguishes between voiced and voiceless unaspirated initial consonants (Mandarin has no voicing of initial consonants). Unlike English, it differentiates between unaspirated and aspirated voiceless initial consonants (as Mandarin does too). In less technical terms, native Amoy speakers have little difficulty in hearing the difference between the following syllables:

| unaspirated | aspirated | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| bilabial stop | bo 母 | po 保 | pʰo 抱 |

| velar stop | go 俄 | ko 果 | kʰo 科 |

| voiced | voiceless | ||

However, these fully voiced consonants did not derive from the Early Middle Chinese voiced obstruents, but rather from fortition of nasal initials.[7]

Accents

A comparison between Amoy and other Southern Min languages can be found there.

Tones

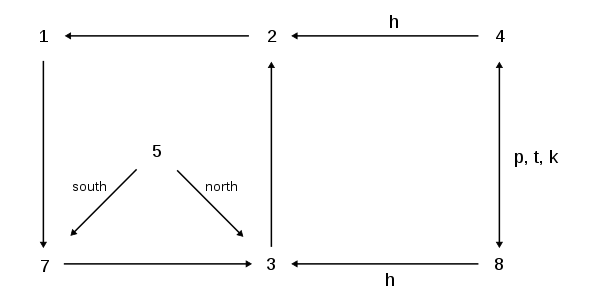

Amoy is similar to other Southern Min variants in that it makes use of five tones, though only two in checked syllables. The tones are traditionally numbered from 1 through 8, with 4 and 8 being the checked tones, but those numbered 2 and 6 are identical in most regions.

| Tone number | Tone name | Tone letter |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yin level | ˥ |

| 2 | Yin rising | ˥˧ |

| 3 | Yin falling | ˨˩ |

| 4 | Yin entering | ˩ʔ |

| 5 | Yang level | ˧˥ |

| 6=2 | Yang rising | ˥˧ |

| 7 | Yang falling | ˧ |

| 8 | Yang entering | ˥ʔ |

Tone sandhi

Amoy has extremely extensive tone sandhi (tone-changing) rules: in an utterance, only the last syllable pronounced is not affected by the rules. What an 'utterance' is, in the context of this language, is an ongoing topic for linguistic research. For the purpose of this article, an utterance may be considered a word, a phrase, or a short sentence. The diagram illustrates the rules that govern the pronunciation of a tone on each of the syllables affected (that is, all but the last in an utterance):

Literary and colloquial readings

Like other languages of Southern Min, Amoy has complex rules for literary and colloquial readings of Chinese characters. For example, the character for big/great, 大, has a vernacular reading of tōa ([tua˧]), but a literary reading of tāi ([tai˧]). Because of the loose nature of the rules governing when to use a given pronunciation, a learner of Amoy must often simply memorize the appropriate reading for a word on a case by case basis. For single-syllable words, it is more common to use the vernacular pronunciation. This situation is comparable to the on and kun readings of the Japanese language.

The vernacular readings are generally thought to predate the literary readings; the literary readings appear to have evolved from Middle Chinese. The following chart illustrates some of the more commonly seen sound shifts:

| Colloquial | Literary | Example | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [p-], [pʰ-] | [h-] | 分 | pun | hun | divide |

| [ts-], [tsʰ-], [tɕ-], [tɕʰ-] | [s-], [ɕ-] | 成 | chiâⁿ | sêng | to become |

| [k-], [kʰ-] | [tɕ-], [tɕʰ-] | 指 | kí | chí | finger |

| [-ã], [-uã] | [-an] | 看 | khòaⁿ | khàn | to see |

| [-ʔ] | [-t] | 食 | chia̍h | si̍t | to eat |

| [-i] | [-e] | 世 | sì | sè | world |

| [-e] | [-a] | 家 | ke | ka | family |

| [-ia] | [-i] | 企 | khiā | khì | to stand |

Vocabulary

- For further information, read the article: Swadesh list

The Swadesh word list, developed by the linguist Morris Swadesh, is used as a tool to study the evolution of languages. It contains a set of basic words which can be found in every language.

- The Amoy Min Nan Swadesh list

- The Sino-Tibetan Swadesh lists (Mandarin, Amoy, Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka, Burmese)

Finals

| a 阿 |

ɔ 乌 |

i 魚 |

e 火 |

o 好 |

u 母 | /ai/ 愛 | /au/ 抱 | |

| /i/- | /ia/ 命 | /io/ 后 | /iu/ 救 |

/iau/ 鸟 | ||||

| /u/- | /ua/ 花 | /ue/ 話 |

/ui/ 水 | /uai/ 歪 |

| /m̩/ 毋 | /am/ 暗 | /an/ 按 | /ŋ̍/ 黃 | /aŋ/ 港 | /ɔŋ/ 風 | |

| /im/ 心 | /iam/ 薟 | /in/ 今 | /iɛn/ 免 | /iŋ/ 英 | /iaŋ/ 雙 | iɔŋ 恭 |

| /un/ 恩 |

/uan/ 完 |

| /ap/ 十 |

/at/ 克 | /ak/ 六 | /ɔk/ 乐 | /aʔ/ 鸭 | ɔʔ 索 | oʔ 學 | /eʔ/ 欲 | /auʔ/ 落 | ãʔ | ɔ̃ʔ 乎 | /ẽʔ/ 夹 | ãiʔ | ||||||

| ip 急 | /iap/ 葉 | /it/ 必 | /iɛt/ 阅 | /ik/ 色 | /iɔk/ 祝 |

iʔ 捏 | /iaʔ 食 | ioʔ 尺 | /iuʔ/ | /ĩʔ/ 物 | iãʔ | |||||||

| /ut/ 骨 | /uat/ 越 | /uʔ/ 嗍 | /uaʔ/ 活 | /ueʔ/ 狹 | /uẽʔ/ |

| /ã/ 三 |

/ɔ̃/ 魯 | /ẽ/ 明 | /ãi/ 歹 | |||

| /ĩ/ 暝 | /iã/ 定 | /iũ/ 想 | /ãu/ 腦 | |||

| /uã/ 山 | /uĩ/ 莓 | /uãi/ |

Grammar

Amoy grammar shares a similar structure to other Chinese dialects, although it is slightly more complex than Mandarin. Moreover, equivalent Amoy and Mandarin particles are usually not cognates.

Complement constructions

Amoy complement constructions are roughly parallel to Mandarin ones, although there are variations in the choice of lexical term. The following are examples of constructions that Amoy employs.

In the case of adverbs:

- English: He runs quickly.

- Amoy: i cháu ē kín (伊走會緊)

- Mandarin: tā pǎo de kuài (他跑得快)

- Gloss: He-runs-obtains-quick.

In the case of the adverb "very":

- English: He runs very quickly.

- Amoy: i cháu chin kín (伊走真緊)

- Mandarin: tā pǎo de hěn kuài (他跑得很快)

- Gloss: He-runs-obtains-quick.

- English: He does not run quickly.

- Amoy: i cháu buē kín (伊走𣍐緊)

- Mandarin: tā pǎo bù kuài (他跑不快)

- Gloss: He-runs-not-quick

- English: He can see.

- Amoy: i khòaⁿ ē tio̍h (伊看會著)

- Mandarin: tā kàn de dào (他看得到)

- Gloss: He-see-obtains-already-achieved

For the negative,

- English: He cannot see.

- Amoy: i khòaⁿ buē tio̍h (伊看𣍐著)

- Mandarin: tā kàn bù dào (他看不到)

- Gloss: He-sees-not-already achieved

For the adverb "so," Amoy uses kah (甲) instead of Mandarin de (得):

- English: He was so startled, that he could not speak.

- Amoy: i kiaⁿ "kah" ōe tio̍h kóng boē chhut-lâi (伊驚甲話著講𣍐出來)

- Mandarin: tā xià de huà dōu shuō bù chūlái (他嚇得話都說不出來)

- Gloss: He-startled-to-the point of-words-also-say-not-come out

Negative particles

Negative particle syntax is parallel to Mandarin about 70% of the time, although lexical terms used differ from those in Mandarin. For many lexical particles, there is no single standard Hanji character to represent these terms (e.g. m̄, a negative particle, can be variously represented by 毋, 呣, and 唔), but the most commonly used ones are presented below in examples. The following are commonly used negative particles:

- m̄ (毋,伓) - is not + noun (Mandarin 不, bù)

- i m̄-sī gún lāu-bú. (伊毋是阮老母) She is not my mother.

- m̄ - does not + verb/will not + verb (Mandarin 不, bù)

- i m̄ lâi. (伊毋來) He will not come.

- verb + buē (𣍐) + particle - is not able to (Mandarin 不, bù)

- góa khòaⁿ-buē-tio̍h. (我看𣍐著) I am not able to see it.

- bē (未) + helping verb - cannot (opposite of ē 會, is able to/Mandarin 不, bù)

- i buē-hiáu kóng Eng-gú. (伊𣍐曉講英語) He can't speak English.

- helping verbs that go with buē (𣍐)

- buē-sái (𣍐使) - is not permitted to (Mandarin 不可以 bù kěyǐ)

- buē-hiáu (𣍐曉) - does not know how to (Mandarin 不会, búhuì)

- buē-tàng (𣍐當) - not able to (Mandarin 不能, bùnéng)

- mài (莫,勿爱) - do not (imperative) (Mandarin 別, bié)

- mài kóng! (莫講) Don't speak!

- bô (無) - do not + helping verb (Mandarin 不, bù)

- i bô beh lâi. (伊無欲來) He is not going to come.

- helping verbs that go with bô (無):

- beh (欲) - want to + verb; will + verb

- ài (愛) - must + verb

- èng-kai (應該) - should + verb

- kah-ì (合意) - like to + verb

- bô (無) - does not have (Mandarin 沒有, méiyǒu)

- i bô chîⁿ. (伊無錢) He does not have any money.

- bô - did not (Mandarin 沒有, méiyǒu)

- i bô lâi. (伊無來) He did not come.

- bô (無) - is not + adjective (Mandarin 不, bù)

- i bô súi. (伊無水 or 伊無媠) She is not beautiful.

- Hó (好)(good) is an exception, as it can use both m̄ and bô.

Common particles

Commonly seen particles include:

- 與 (hō·) - indicates passive voice (Mandarin 被, bèi)

- i hō· lâng phiàn khì (伊與人騙去) - They were cheated

- 共 (kā) - identifies the object (Mandarin 把, bǎ)

- i kā chîⁿ kau hō· lí (伊共錢交與你) - He handed the money to you

- 加 (ke) - "more"

- i ke chia̍h chi̍t óaⁿ (伊加食一碗) - He ate one more bowl

- 共 (kā) - identifies the object

- góa kā lí kóng (我共你講) - I'm telling you

- 濟 (choē) - "more"

- i ū khah choē ê pêng-iú (伊有較濟的朋友) - He has comparatively many friends

Romanization

A number of Romanization schemes have been devised for Amoy. Pe̍h-ōe-jī is one of the oldest and best established. However, the Taiwanese Language Phonetic Alphabet has become the romanization of choice for many of the recent textbooks and dictionaries from Taiwan.

| IPA | a | ap | at | ak | aʔ | ã | ɔ | ɔk | ɔ̃ | ə | o | e | ẽ | i | iɛn | iəŋ |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | a | ap | at | ak | ah | aⁿ | o͘ | ok | oⁿ | o | o | e | eⁿ | i | ian | eng |

| Revised TLPA | a | ap | at | ak | ah | aN | oo | ok | ooN | o | o | e | eN | i | ian | ing |

| TLPA | a | ap | at | ak | ah | ann | oo | ok | oonn | o | o | e | enn | i | ian | ing |

| BP | a | ap | at | ak | ah | na | oo | ok | noo | o | o | e | ne | i | ian | ing |

| MLT | a | ab/ap | ad/at | ag/ak | aq/ah | va | o | og/ok | vo | ø | ø | e | ve | i | ien | eng |

| DT | a | āp/ap | āt/at | āk/ak | āh/ah | ann/aⁿ | o | ok | onn/oⁿ | or | or | e | enn/eⁿ | i | ian/en | ing |

| Taiwanese kana | アア | アㇷ゚ | アッ | アㇰ | アァ | アア | オオ | オㇰ | オオ | オオ | ヲヲ | エエ | エエ | イイ | イェヌ | イェン |

| Extended bopomofo | ㄚ | ㄚㆴ | ㄚㆵ | ㄚㆶ | ㄚㆷ | ㆩ | ㆦ | ㆦㆶ | ㆧ | ㄜ | ㄛ | ㆤ | ㆥ | ㄧ | ㄧㄢ | ㄧㄥ |

| Tâi-lô | a | ap | at | ak | ah | ann | oo | ok | onn | o | o | e | enn | i | ian | ing |

| Example (traditional Chinese) | 亞 洲 |

壓 力 |

警 察 |

沃 水 |

牛 肉 |

三 十 |

烏 色 |

中 國 |

澳 洲 |

澳 洲 |

下 晡 |

醫 學 |

鉛 筆 |

英 國 | ||

| Example (simplified Chinese) | 亚 洲 |

压 力 |

警 察 |

沃 水 |

牛 肉 |

三 十 |

乌 色 |

中 国 |

澳 洲 |

澳 洲 |

下 晡 |

医 学 |

铅 笔 |

英 国 |

| IPA | iək | ĩ | ai | aĩ | au | am | ɔm | m̩ | ɔŋ | ŋ̍ | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | ɨ | (i)ũ |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | ek | iⁿ | ai | aiⁿ | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | oa | oe | oai | oan | i | (i)uⁿ |

| Revised TLPA | ik | iN | ai | aiN | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | ir | (i)uN |

| TLPA | ik | inn | ai | ainn | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | ir | (i)unn |

| BP | ik | ni | ai | nai | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | i | n(i)u |

| MLT | eg/ek | vi | ai | vai | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | oa | oe | oai | oan | i | v(i)u |

| DT | ik | inn/iⁿ | ai | ainn/aiⁿ | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | i | (i)unn/uⁿ |

| Taiwanese kana | イェㇰ | イイ | アイ | アイ | アウ | アム | オム | ム | オン | ン | ウウ | ヲア | ヲエ | ヲァイ | ヲァヌ | ウウ | ウウ |

| Extended bopomofo | ㄧㆶ | ㆪ | ㄞ | ㆮ | ㆯ | ㆰ | ㆱ | ㆬ | ㆲ | ㆭ | ㄨ | ㄨㄚ | ㄨㆤ | ㄨㄞ | ㄨㄢ | ㆨ | ㆫ |

| Tâi-lô | ik | inn | ai | ainn | au | am | om | m | ong | ng | u | ua | ue | uai | uan | ir | (i)unn |

| Example (traditional Chinese) | 翻 譯 |

病 院 |

愛 情 |

歐 洲 |

暗 時 |

阿 姆 |

王 梨 |

黃 色 |

有 無 |

歌 曲 |

講 話 |

奇 怪 |

人 員 |

豬 肉 |

舀 水 | ||

| Example (simplified Chinese) | 翻 译 |

病 院 |

爱 情 |

欧 洲 |

暗 时 |

阿 姆 |

王 梨 |

黄 色 |

有 无 |

歌 曲 |

讲 话 |

奇 怪 |

人 员 |

猪 肉 |

舀 水 |

| IPA | p | b | pʰ | m | t | tʰ | n | nŋ | l | k | ɡ | kʰ | h | tɕi | ʑi | tɕʰi | ɕi | ts | dz | tsʰ | s |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | chi | ji | chhi | si | ch | j | chh | s |

| Revised TLPA | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | zi | ji | ci | si | z | j | c | s |

| TLPA | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | zi | ji | ci | si | z | j | c | s |

| BP | b | bb | p | bb | d | t | n | lng | l | g | gg | k | h | zi | li | ci | si | z | l | c | s |

| MLT | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | ci | ji | chi | si | z | j | zh | s |

| DT | b | bh | p | m | d | t | n | nng | l | g | gh | k | h | zi | r | ci | si | z | r | c | s |

| Taiwanese kana | パア | バア | パ̣ア | マア | タア | タ̣ア | ナア | ヌン | ラア | カア | ガア | カ̣ア | ハア | チイ | ジイ | チ̣イ | シイ | サア | ザア | サ̣ア | サア |

| Extended bopomofo | ㄅ | ㆠ | ㄆ | ㄇ | ㄉ | ㄊ | ㄋ | ㄋㆭ | ㄌ | ㄍ | ㆣ | ㄎ | ㄏ | ㄐ | ㆢ | ㄑ | ㄒ | ㄗ | ㆡ | ㄘ | ㄙ |

| Tâi-lô | p | b | ph | m | t | th | n | nng | l | k | g | kh | h | tsi | ji | tshi | si | ts | j | tsh | s |

| Example (traditional Chinese) | 報 紙 |

閩 南 |

普 通 |

請 問 |

豬 肉 |

普 通 |

過 年 |

雞 卵 |

樂 觀 |

價 值 |

牛 奶 |

客 廳 |

煩 惱 |

支 持 |

漢 字 |

支 持 |

是 否 |

報 紙 |

熱 天 |

參 加 |

司 法 |

| Example (simplified Chinese) | 报 纸 |

闽 南 |

普 通 |

请 问 |

猪 肉 |

普 通 |

过 年 |

鸡 卵 |

乐 观 |

价 值 |

牛 奶 |

客 厅 |

烦 恼 |

支 持 |

汉 字 |

支 持 |

是 否 |

报 纸 |

热 天 |

参 加 |

司 法 |

| Tone name | Yin level 陰平(1) | Yin rising 陰上(2) | Yin departing 陰去(3) | Yin entering 陰入(4) | Yang level 陽平(5) | Yang rising 陽上(6) | Yang departing 陽去(7) | Yang entering 陽入(8) | High rising (9) | Neutral tone (0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | a˥ | a˥˧ | a˨˩ | ap˩ at˩ ak˩ aʔ˩ | a˧˥ | a˥˧ | a˧ | ap˥ at˥ ak˥ aʔ˥ | a˥˥ | a˨ |

| Pe̍h-ōe-jī | a | á | à | ap at ak ah | â | á | ā | a̍p a̍t a̍k a̍h | --a | |

| Revised TLPA, TLPA | a1 | a2 | a3 | ap4 at4 ak4 ah4 | a5 | a2 (6=2) | a7 | ap8 at8 ak8 ah8 | a9 | a0 |

| BP | ā | ǎ | à | āp āt āk āh | á | ǎ | â | áp át ák áh | ||

| MLT | af | ar | ax | ab ad ag aq | aa | aar | a | ap at ak ah | ~a | |

| DT | a | à | â | āp āt āk āh | ǎ | à | ā | ap at ak ah | á | å |

| Taiwanese kana (normal vowels) | アア | アア | アア | アㇷ゚ アッ アㇰ アァ | アア | アア | アア | アㇷ゚ アッ アㇰ アァ | ||

| Taiwanese kana (nasal vowels) | アア | アア | アア | アㇷ゚ アッ アㇰ アァ | アア | アア | アア | アㇷ゚ アッ アㇰ アァ | ||

| Extended bopomofo | ㄚ | ㄚˋ | ㄚ˪ | ㄚㆴ ㄚㆵ ㄚㆶ ㄚㆷ | ㄚˊ | ㄚˋ | ㄚ˫ | ㄚㆴ˙ ㄚㆵ˙ ㄚㆶ˙ ㄚㆷ˙ | ||

| Tâi-lô | a | á | à | ah | â | á (ǎ) | ā | a̍h | a̋ | --a |

| Example (traditional Chinese) |

公司 | 報紙 | 興趣 | 血壓 警察 中國 牛肉 |

人員 | 草地 | 配合 法律 文學 歇熱 |

社子 | 進去 | |

| Example (simplified Chinese) |

公司 | 报纸 | 兴趣 | 血压 警察 中国 牛肉 |

人员 | 草地 | 配合 法律 文学 歇热 |

社子 | 进去 |

See also

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Xiamen". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Lee, Alan (January 1, 2005). Tone patterns of Kelantan Hokkien and related issues in Southern Min tonology (Ph.D. in Linguistics). ProQuest. OCLC 244974990.

- ↑ Heylen, Ann (2001). "Missionary linguistics on Taiwan. Romanizing Taiwanese: codification and standardization of dictionaries in Southern Min (1837-1923)". In Ku, Wei-ying; De Ridder, Koen. Authentic Chinese Christianity : Preludes to its development (Nineteenth and twentieth centuries). Leuven: Leuven University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9789058671028.

- ↑ Niú, Gēngsǒu. 台湾河洛话发展历程 [The Historical Development of Taiwanese Hoklo]. 中国台湾网 聚焦台湾 携手两岸 (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2014-05-17.

- ↑ "Chinese, Min Nan". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ↑ "The Ancient Minyue People and the Origins of the Min Nan Language". Jinjiang Government website (in Chinese). Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ↑ "Contact-Induced Phonological Change in Taiwanese". OhioLINK.edu. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

Sources

- Huanan, Wang (2007). 愛說台語五千年 -- 台語聲韻之美 [To understand the beauty of Taiwanese] (in Chinese). ISBN 978-986-7101-47-1.

- Shunliang (2004). 華台英詞彙句式對照集 [Chinese-Taiwanese-English Lexicon] (in Chinese and English). ISBN 957-11-3822-3.

- Tang, Tingchi (1999). 閩南語語法研究試論 [Papers on Southern Min Syntax] (in Chinese and English). ISBN 957-15-0948-5.

- Douglas, Carstairs (1899) [1873]. Chinese-English dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy (2nd ed.). London: Presbyterian Church of England. OL 25126855M.

- Barclay, Thomas (1923). Supplement to Dictionary of the vernacular or spoken language of Amoy. Shanghai: The Commercial press, limited.

- MacGowan, John (1898). A manual of the Amoy colloquial (4th ed.). Amoy: Chui Keng Ton. OCLC 41546744. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

External links

| Chinese (Min Nan) edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Look up Appendix:Min Nan Swadesh list in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- {Why it is Called Amoy}, Why Minnan is called "Amoy"

- listen to the news in Amoy Min Nan (site is in Chinese script)

- Database of Pronunciations of Chinese Dialects (in English, Chinese and Japanese)

- Glossika - Chinese Languages and Dialects

- Voyager - Spacecraft - Golden Record - Greetings From Earth - Amoy, includes translation and sound clip

- (The voyager clip says: Thài-khong pêng-iú, lín-hó. Lín chia̍h-pá--bē? Ū-êng, to̍h lâi gún chia chē--ô·! 太空朋友,恁好。恁食飽未?有閒著來阮遮坐哦!)