Buryat language

| Buryat | |

|---|---|

| Buriat | |

| буряад хэлэн buryaad xelen | |

| Native to | Russia (Buryat Republic, Ust-Orda Buryatia, Aga Buryatia), northern Mongolia, China (Hulunbuir) |

| Ethnicity | Buryats, Barga Mongols |

Native speakers | (265,000 in Russia and Mongolia (2010 census); 65,000 in China cited 1982 census)[1] |

|

Mongolic

| |

| Cyrillic, Mongolian script, Vagindra script, Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

bua Buriat |

| ISO 639-3 |

bua – inclusive code BuriatIndividual codes: bxu – China Buriatbxm – Mongolia Buriatbxr – Russia Buriat |

| Glottolog |

buri1258 Buriat[2] |

| Linguasphere |

part of 44-BAA-b |

Buryat or Buriat[1][2] (/ˈbʊriæt/;[3] Buryat Cyrillic: буряад хэлэн, buryaad xelen) is a variety of the Mongolic languages spoken by the Buryats that is classified either as a language or major dialect group of Mongolian.

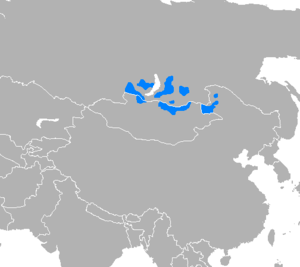

Geographic distribution

The majority of Buryat speakers live in Russia along the northern border of Mongolia where it is an official language in the Buryat Republic, Ust-Orda Buryatia and Aga Buryatia.[4] In the Russian census of 2002, 353,113 people out of an ethnic population of 445,175 reported speaking Buryat (72.3%). Some other 15,694 can also speak Buryat, mostly ethnic Russians.[5] There are at least 100,000 ethnic Buryats in Mongolia and the People's Republic of China as well.[6] Buryats in Russia have a separate literary standard, written in a Cyrillic alphabet.[7] It is based on the Russian alphabet with three additional letters: Ү/ү, Ө/ө and Һ/һ.

Dialects

The delimitation of Buryat mostly concerns its relationship to its immediate neighbors, Mongolian proper and Khamnigan. While Khamnigan is sometimes regarded as a dialect of Buryat, this is not supported by isoglosses. The same holds for Tsongol and Sartul dialects, which rather group with Khalkha Mongolian to which they historically belong. Buryat dialects are:

- Khori group east of Lake Baikal comprising Khori, Aga, Tugnui, and North Selenga dialects. Khori is also spoken by most Buryats in Mongolia and a few speakers in Hulunbuir.

- Lower Uda (Nizhneudinsk) dialect, the dialect situated furthest to the west and which shows the strongest influence by Turkic

- Alar–Tunka group comprising Alar, Tunka–Oka, Zakamna, and Unga in the southwest of Lake Baikal in the case of Tunka also in Mongolia.

- Ekhirit–Bulagat group in the Ust’-Orda National District comprising Ekhirit–Bulagat, Bokhan, Ol’khon, Barguzin, and Baikal–Kudara

- Bargut group in Hulunbuir (which is historically known as Barga), comprising Old Bargut and New Bargut[8]

Based on loan vocabulary, a division might be drawn between Russia Buriat, Mongolia Buriat and China Buriat.[9] However, as the influence of Russian is much stronger in the dialects traditionally spoken west of Lake Baikal, a division might rather be drawn between the Khori and Bargut group on the one hand and the other three groups on the other hand.[10]

Phonology

Buryat has the vowel phonemes /i, ɯ, e, a, u, ʊ, o, ɔ/ (plus a few diphthongs),[11] short /e/ being realized as [ɯ], and the consonant phonemes /b, g, d, p, t, tʰ, m, n, x, l, r/ (each with a corresponding palatalized phoneme) and /s, ʃ, z, ʒ, h, j/.[12][13] These vowels are restricted in their occurrence according to vowel harmony.[14] The basic syllable structure is (C)V(C) in careful articulation, but word-final CC clusters may occur in more rapid speech if short vowels of non-initial syllables get dropped.[15]

Stress

Lexical stress (word accent) falls on the last heavy nonfinal syllable when one exists. Otherwise, it falls on the word-final heavy syllable when one exists. If there are no heavy syllables, then the initial syllable is stressed. Heavy syllables without primary stress receive secondary stress:[16]

ˌHˈHL [ˌøːɡˈʃøːxe] "to act encouragingly" LˌHˈHL [naˌmaːˈtuːlxa] "to cause to be covered with leaves" ˌHLˌHˈHL [ˌbuːzaˌnuːˈdiːje] "steamed dumplings (accusative)" ˌHˈHLLL [ˌtaːˈruːlaɡdaxa] "to be adapted to" ˈHˌH [ˈboːˌsoː] "bet" LˈHˌH [daˈlaiˌɡaːr] "by sea" LˈHLˌH [xuˈdaːliŋɡˌdaː] "to the husband's parents" LˌHˈHˌH [daˌlaiˈɡaːˌraː] "by one's own sea" ˌHLˈHˌH [ˌxyːxenˈɡeːˌreː] "by one's own girl" LˈH [xaˈdaːr] "through the mountain" ˈLL [ˈxada] "mountain"[17]

Secondary stress may also occur on word-initial light syllables without primary stress, but further research is required. The stress pattern is the same as in Khalkha Mongolian.[16]

Writing systems

Buryat (Latin) alphabet between 1931 and 1939

| A a | B b | C c | Ç ç | D d | E e | F f | G g |

| H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | M m | N n | O o |

| Ө ө | P p | R r | S s | Ş ş | T t | U u | V v |

| X x[18] | Y y | Z z | Ƶ ƶ | ь[18] |

Buryat alphabet (Cyrillic)

| А а | Б б | В в | Г г | Д д | Е е | Ё ё | Ж ж |

| З з | И и | Й й | К к | Л л | М м | Н н | О о |

| Ө ө | П п | Р р | С с | Т т | У у | Ү ү | Ф ф |

| Х х | Һ һ | Ц ц | Ч ч | Ш ш | Щ щ | Ъ ъ | Ы ы |

| Ь ь | Э э | Ю ю | Я я |

Grammar

Buryat is an SOV language that makes exclusive use of postpositions. Buryat is equipped with eight grammatical cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, instrumental, ablative, comitative, dative-locative and a particular oblique form of the stem.[19]

Numerals

| English | Classical Mongolian | Buryat | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | One | Nig | Negen |

| 2 | Two | Hoyor | Xoyor |

| 3 | Three | Gurav | Gurban |

| 4 | Four | Duruv | Dürben |

| 5 | Five | Tav | Taban |

| 6 | Six | Zurgaa | Zurgaan |

| 7 | Seven | Doloo | Doloon |

| 8 | Eight | Naim | Nayman |

| 9 | Nine | Yoos | Yühen |

| 10 | Ten | Arav | Arban |

Notes

- 1 2 Buriat at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

China Buriat at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

Mongolia Buriat at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

Russia Buriat at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016) - 1 2 Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Buriat". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ Skribnik 2003: 102, 105

- ↑ Russian Census (2002)

- ↑ Skribnik 2003: 102

- ↑ Skribnik 2003: 105

- ↑ Skribnik 2003: 104

- ↑ Gordon (ed.) 2005

- ↑ Skribnik 2003: 102, 104

- ↑ Poppe 1960: 8

- ↑ Svantesson, Tsendina and Karlsson 2008, p. 146.

- ↑ Svantesson et al. 2005: 146; the status of [ŋ] is problematic, see Skribnik 2003: 107. In Poppe 1960's description, places of vowel articulation are somewhat more fronted.

- ↑ Skribnik 2003: 107

- ↑ Poppe 1960: 13-14

- 1 2 Walker 1997

- ↑ Walker 1997: 27-28

- 1 2 Letter established in 1937

- ↑ "Overview of the Buriat Language". Learn the Buriat Language & Culture. Transparent Language. Retrieved 4 Nov 2011.

References

- Poppe, Nicholas (1960): Buriat grammar. Uralic and Altaic series (No. 2). Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Skribnik, Elena (2003): Buryat. In: Juha Janhunen (ed.): The Mongolic languages. London: Routledge: 102-128.

- Svantesson, Jan-Olof, Anna Tsendina, Anastasia Karlsson, Vivan Franzén (2005): The Phonology of Mongolian. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Walker, Rachel (1997): Mongolian stress, licensing, and factorial typology. (Online on the Rutgers Optimality Archive website: roa.rutgers.edu/view.php3?id=184.)

Further reading

- Санжеев Г. Д. (1962). Грамматика бурятского языка. Фонетика и морфология [Sanzheev, G.D. Grammar of Buryat. Phonetics and morphology] (PDF, 23 Mb) (in Russian).

- (ru) Н. Н. Поппе, Бурят-монгольское языкознание, Л., Изд-во АН СССР, 1933

- Anthology of Buryat folklore, Pushkinskiĭ dom, 2000 (CD)

External links

| Buryat edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |