Teochew dialect

| Teo-Swa | |

|---|---|

| Chaoshan | |

| 潮州話/潮汕話 | |

| Native to | China, overseas Chinese communities |

| Region | eastern Guangdong (Chaoshan), southern Fujian (Zhao'an) |

| Ethnicity | Han Chinese (Teochew people) |

Native speakers | About 10 million in Chaoshan, 2–5 million overseas |

|

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog |

teoc1236 Teochew[1]chao1238 Chaozhou[2]chao1239 Chaoshan[3] |

| Linguasphere |

79-AAA-ji |

Teo-Swa | |

| Teochew dialect | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 潮州話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 潮州话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chaoshan dialect | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 潮汕話 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 潮汕话 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

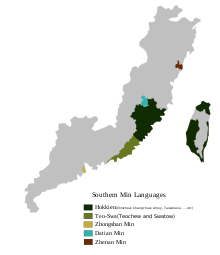

Teochew (Chinese: 潮州話 or 潮汕話; pinyin: Cháozhōuhuà or Cháoshànhuà, Chaozhou dialect: Diê⁵ziu¹ uê⁷; Shantou dialect: Dio⁵ziu¹ uê⁷) is a variant of Southern Min spoken mainly by the Teochew people in the Chaoshan region of eastern Guangdong and by their diaspora around the world. It is sometimes referred to as Chiuchow, its Cantonese name, due to the strong influence of that language over the traditionally Teochew-speaking areas.[4] It is closely related to its mainstream counterpart, Minnan Proper (Hokkien-Taiwanese), as it shares some cognates and have a highly similar phonology with it though limited mutual intelligibility exists in terms of pronunciation and vocabulary between them.

Teochew preserves many Old Chinese pronunciations and vocabulary that have been lost in some of the other modern varieties of Chinese. As such, many linguists consider Teochew one of the most conservative Chinese dialects.[5]

Classification

Teochew is a variant of the Southern Min, which in turn constitutes a part of Min Chinese, one of the seven major language groups of Chinese. As with other varieties of Chinese, it is not mutually intelligible with Mandarin, Cantonese, Shanghainese and other Chinese varieties. However, it has limited intelligibility with the Quanzhang dialects (Minnan Proper) under the greater Southern Min language, such as those of Amoy, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou and Taiwanese. Even within the Teochew dialects, there is substantial variation in phonology between different regions of Chaoshan and between different Teochew communities overseas.

The Chaoshan dialects in China be roughly divided into three sub-groups defined by physically proximate areas:

History and geography

The Chaoshan region, which includes the twin cities of Chaozhou and Shantou, is where the standard variant of Teochew (Chaoshan dialact) is spoken. Parts of the Hakka-speaking regions of Jiexi County, Dabu County and Fengshun, also contain pocket communities of Teochew speakers.

As Chaoshan was one of the major sources of Chinese emigration to Southeast Asia during the 18th to 20th centuries, a considerable Overseas Chinese community in that region is Teochew-speaking. In particular, the Teochew people settled in significant numbers in Cambodia, Thailand and Laos, where they form the largest Chinese sub-language group. Teochew-speakers form a minority among Chinese communities in Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia (especially in the states of Johor and Selangor) and Indonesia (especially in West Kalimantan on Borneo). Waves of migration from Chaoshan to Hong Kong, especially after the communist victory of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, has also resulted in the formation of a community there, although most descendants now primarily speak Cantonese and English.

Teochew speakers are also found among overseas Chinese communities in Japan and the Western world (notably in the United States, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, France and Italy), a result of both direct emigration from Chaoshan to these nations and secondary emigration from Southeast Asia.

In Singapore, due to the local government's stringent bilingual policy such as making English as the official language of education, government and commerce and the promotion of Mandarin Speak Mandarin Campaign at the expense of other Chinese varieties, many Chinese Singaporeans whose ancestral language is Teochew are converting to mainly English and Mandarin. Some of them spoke Cantonese due to the popularity of Hong Kong Cantonese entertainment media and pop songs. Some of them are assimilated into Minnan Proper (Hokkien-Taiwanese) due to the fact that Minnan Proper is the mainstream Fujian dialect and the similarities that exist between the two Min Nan variants, coupled with the recent emergence the Taiwanese Min Nan Television shows and Pop music. Teochew remains the ancestral language of many Chinese people in Singapore - Teochew people are the second largest Chinese group in Singapore, after the Hoklos (Minnan) - although English and/or Mandarin is gradually supplanting Teochew as their main language used for communication, especially amongst the younger generations.

In Thailand, particularly in the Bangkok, Teochew is still spoken among older ethnic Chinese Thai citizens; however, the younger generation tends to learn Standard Mandarin and/or Standard Cantonese as a second or third language after Thai and English.

Teochew was never popular in Chinese communities in Japan and South Korea, since most of the Teochew people who migrated to these countries are secondary immigrants from Hong Kong and Taiwan. Most of them are second-generation people from Hong Kong and Taiwan who speak Cantonese, Hokkien-Taiwanese and Mandarin, as well as Korean and Japanese, leaving Teochew to be spoken mostly by elders.

Relationship with Southern Min (Minnan Proper / Quanzhang / Hokkien-Taiwanese)

Teochew is a variant of Minnan under the greater Southern Min language. It is one of the more well known Min language varieties besides Minnan spoken in Southern Fujian and Fuzhou dialect spoken in Fuzhou capital of Fujian. Teochew culture is similar to Minnan culture. It shares the same linguistic historical roots with Minnan. It is highly phonetically similar to Minnan Proper but has low lexical similarity with it. Teochew shares some cognates with Minnan Proper, the difference is most pronounced in most vowels, some consonants and tone shifts. Some of its vocabulary and phrases are distinct from Minnan Proper. Teochew is treated separately from Minnan. Despite the closeness of the two, they are mutually intelligible to a small degree.

Although Minnan is the mainstream Southern Min language and is spoken in Teochew speaking region's closest neighbour, Southern Fujian towards the northeast, most Teochew people do not speak it and the majority see themselves as a distinct group from their mainstream counterparts in their neighbouring Southern Fujian. Most can at least understand Minnan marginally and they treat Minnan as an improper form of their own tongue. However, there are a minority group of Teochew people who speak Minnan exclusively, most of whom have had relatives and close contacts with their mainstream counterparts from their neighbouring Southern Fujian. For these Minnan speaking Teochews, Minnan is highly considered as their native language as well and they treat their hometown language as a merely accented form of Minnan. They usually have a strong sense of identity as Hoklo Minnan people and they integrate easily into the mainstream Southern Min culture.

Languages in contact

This refers to Chaozhou, the variant of Southern Min (Min Nan) spoken in China.

Mandarin

Chaozhou children are introduced to Standard Chinese as early as in kindergarten; however, Chaozhou remains the primary medium of instruction. In the early years of primary education, Mandarin becomes the sole language of instruction, although students typically continue to talk to one another in Chaozhou. Mandarin is widely understood, however minimally, by most younger Chaozhou speakers, but the elderly usually do not speak Mandarin since teaching was done in the local vernacular in the past.

Chaozhou accent in Mandarin

Native Chaozhou speakers find the neutral tone in Mandarin hardest to master. Chaozhou has lost the alveolar nasal ending [-n] and so the people often replace the sound in Mandarin with the velar nasal [-ŋ]. None of the southern Min dialects have a front rounded vowel, therefore a typical Chaozhou accent supplants the unrounded counterpart [i] for [y]. Chaozhou, like its ancient ancestor, lacks labio-dentals; people therefore substitute [h] or [hu] for [f] when they speak Mandarin. Chaozhou does not have any of the retroflex consonants in the northern dialects, so they pronounce [ts], [tsʰ], [s], and [z] instead of [tʂ], [tʂʰ], [ʂ] and [ʐ].

Hakka

Since Chao'an, Raoping and Jieyang border the Hakka-speaking region in the north, some people in these regions speak Hakka, though they can usually speak Chaozhou as well. Chaozhou people have historically had a great deal of contact with the Hakka people, but Hakka has had little, if any, influence on Chaozhou. Similarly, in Dabu and Fengshun, where the Chaozhou- and Hakka-speaking regions meet, Chaozhou is also spoken although Hakka remains the primary form of Chinese spoken there.

Cantonese

Because of the strong influence of Hong Kong soap operas, Guangdong provincial television programs and Cantonese pop songs, many young Chaoshan peoples can understand quite a lot of Cantonese even if they cannot speak it in certain degrees of fluency.

Other languages

In the mountainous area of Fenghuang (凤凰山; 鳳凰山), the She language, an endangered Hmong–Mien language, is spoken by the She people, who are an officially recognised non-Han ethnic minority. They predominantly speak Hakka and Teochew; only about 1,000 She still speak their eponymous language.

Phonetics and phonology

Consonants

Teochew, like other Southern Min varieties, is one of the few modern Sinitic languages which have voiced obstruents (stops, fricatives and affricates); however, unlike Wu and Xiang Chinese, the Teochew voiced stops and fricatives did not evolve from Middle Chinese voiced obstruents, but from nasals. The voiced stops [b] and [ɡ] and also [l] are voicelessly prenasalised [ᵐ̥b], [ᵑ̊ɡ], [ⁿ̥ɺ], respectively. They are in complementary distribution with the tenuis stops [p t k], occurring before nasal vowels and nasal codas, whereas the tenuis stops occur before oral vowels and stop codas. The voiced affricate dz, initial in such words as 字 (dzi˩), 二 (dzi˧˥), 然 (dziaŋ˥), 若 (dziak˦) loses its affricate property with some younger speakers abroad, and is relaxed to [z].

Southern Min dialects and varieties are typified by a lack of labiodentals, as illustrated below:

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m 毛 | n 年 | ŋ 雅 | ||

| Stop | aspirated | pʰ 皮 | tʰ 台 | kʰ 可 | |

| voiceless | p 比 | t 都 | k 歌 | ʔ | |

| voiced | b 米 | g 鵝/牙 | |||

| Affricate | aspirated | tsʰ 菜/樹 | |||

| voiceless | ts 書/指/食 | ||||

| Fricative | s 士/速

(d)z 爾/貳 |

h 海/系

h̃ 園/遠 [h̃ŋ] | |||

| Approximant | l 來/內 | ||||

Syllable

Syllables in Teochew contain an onset consonant, a medial glide, a nucleus, usually in the form of a vowel, but can also be occupied by a syllabic consonant like [ŋ], and a final consonant. All the elements of the syllable except for the nucleus are optional, which means a vowel or a syllabic consonant alone can stand as a fully-fledged syllable.

Onsets

All the consonants except for the glottal stop ʔ shown in the consonants chart above can act as the onset of a syllable; however, the onset position is not obligatorily occupied.

Finals

Teochew finals consist maximally of a medial, nucleus and coda. The medial can be i or u, the nucleus can be a monophthong or diphthong, and the coda can be a nasal or a stop. A syllable must consist minimally of a vowel nucleus or syllabic nasal.

| Nucleus | -a- | -e- | -o- | -ə- | -i- | -u- | -ai- | -au- | -oi- | -ou- | -ui- | -iu- | ∅- | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅- | i- | u- | ∅- | u- | ∅- | i- | ∅- | ∅- | ∅- | ∅- | u- | ∅- | ∅- | ∅- | i- | ∅- | ∅- | ||

| Coda | -∅ | a | ia | ua | e | ue | o | io | ɨ | i | u | ai | uai | au | oi | ou | iou | ui | iu | |

| -◌̃ | ã | ĩã | ũã | ẽ | ũẽ | ĩõ | ɨ̃ | ĩ | ãĩ | ũãĩ | ãũ | õĩ | õũ | ũĩ | ĩũ | |||||

| -ʔ | aʔ | iaʔ | uaʔ | eʔ | ueʔ | oʔ | ioʔ | iʔ | auʔ | oiʔ | ||||||||||

| -m | am | iam | uam | im | m̩ | |||||||||||||||

| -ŋ | aŋ | iaŋ | uaŋ | eŋ | oŋ | ioŋ | əŋ | iŋ | uŋ | ŋ̩ | ||||||||||

| -p | ap | iap | uap | ip | ||||||||||||||||

| -k | ak | iak | uak | ek | ok | iok | ək | ik | uk | |||||||||||

Tones

Citation tones

Teochew, like other Chinese varieties, is a tonal language. It has six tones (reduced to two in stopped syllables) and extensive tone sandhi.

Teochew tones Tone

numberTone name Pitch

contourDescription Sandhi 1 yin level (陰平) ˧ (3) mid 1 2 yin rising (陰上) ˥˨ (52) falling 6 3 yin departing (陰去) ˨˩˧ (213) low rising 2 or 5 4 yin entering (陰入) ˨̚ (2) low checked 8 5 yang level (陽平) ˥ (5) high 7 6 yang rising (陽上) ˧˥ (35) high rising 7 7 yang departing (陽去) ˩ (1) low 7 8 yang entering (陽入) ˦̚ (4) high checked 4

As with sandhi in other Min Nan dialects, the checked tones interchange. The yang tones all become low. Sandhi is not accounted for in the description below.

Grammar

The grammar of Teochew is similar to other Min languages, as well as some southern varieties of Chinese, especially with Hakka, Yue and Wu. The sequence 'subject–verb–object' is typical, like Standard Mandarin, although the 'subject–object–verb' form is also possible using particles.

Morphology

Pronouns

Personal pronouns

The personal pronouns in Teochew, like in other Chinese varieties, do not show case marking, therefore 我 [ua] means both I and me and 伊人 [iŋ] means they and them. The southern Min dialects, like some northern dialects, have a distinction between an inclusive and exclusive we, meaning that when the addressee is being included, the inclusive pronoun 俺 [naŋ] would be used, otherwise 阮 [ŋ]. No other southern Chinese variety has this distinction.

| Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 我 ua˥˨ | I / me | Inclusive | 俺 naŋ˥˨ | we / us |

| Exclusive | 阮 uaŋ˥˨ (uŋ˥˨ / ŋ˥˨) | we / us | |||

| 2nd person | 汝 lɨ˥˨ | you | 恁 niŋ˥˨ | you (plural) | |

| 3rd person | 伊 i˧ | he/she/it/him/her | 伊人 iŋ˧ (i˧ naŋ˥) | they/them | |

Possessive pronouns

Teochew does not distinguish the possessive pronouns from the possessive adjectives. As a general rule, the possessive pronouns or adjectives are formed by adding the genitive or possessive marker 個 [kai5] to their respective personal pronouns, as summarised below:

| Singular | Plural | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | 我個 ua˥˨ kai˥ | my / mine | Inclusive | 俺個 naŋ˥˨ kai˥ | our / ours |

| Exclusive | 阮個 uaŋ˥˨ (uŋ˥˨ / ŋ˥˨) kai˥ | ours / ours | |||

| 2nd person | 汝個 lɨ˥˨ kai˥ | your / yours | 恁個 niŋ˥˨ kai˥ | your / yours (plural) | |

| 3rd person | 伊個 i˧ kai˥ | his / his; her / hers; its / its | 伊人個 iŋ˧ (i˧ naŋ˥) kai˥ | their / theirs | |

- 本書是我個。

- [puŋ˥˨ tsɨ˧ si˧˥ ua˥˨ kai˥]

- The book is mine.

As 個 [kai˥] is the generic measure word, it may be replaced by other more appropriate classifiers:

- 我條裙

- [ua˥˨ tiou˥ kuŋ˥]

- my skirt

Demonstrative pronouns

Teochew has the typical two-way distinction between the demonstratives, namely the proximals and the distals, as summarised in the following chart:

| Proximal | Distal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Singular | 之個 [tsi˥˨ kai˥] | this | 許個 [hɨ˥˨ kai˥] | that |

| Plural | 之撮 [tsi˥˨ tsʰoʔ˦] | these | 許撮 [hɨ˥˨ tsʰoʔ˦] | those | |

| Spatial | 之塊 [tsi˥˨ ko˨˩˧] | here | 許塊 [hɨ˥˨ ko˨˩˧] | there | |

| 之內 [tsi˥˨ lai˧˥] | inside | 許內 [hɨ˥˨ lai˧˥] | inside | ||

| 之口 [tsi˥˨ kʰau˩] | outside | 許口 [hɨ˥˨ kʰau˩] | outside | ||

| Temporal | 之陣 / 當 [tsi˥˨ tsuŋ˥ / təŋ˨˩˧] | now; recently | 許陣 / 當 [hɨ˥˨ tsuŋ˥ / təŋ˨˩˧] | then | |

| Adverbial | 這生 [tse˥˨ sẽ˧] | like this | 向生 [hia˥˨ sẽ˧] | like that | |

| Degree | 之樣 [tsĩõ˨˩˧] | this | 向樣 [hĩõ˨˩˧] | that | |

| Type | 者個 [tsia˥˨ kai˥] | this kind | 向個 [hia˥˨ kai˥] | that kind | |

Interrogative pronouns

| who / whom | (底)珍 [ti tiaŋ] | |

|---|---|---|

| 底人 [ti naŋ] | ||

| what | 乜個 [miʔ kai] | |

| what (kind of) + noun | 乜 + N [miʔ] | |

| which | 底 + NUM + CL + (N) [ti] | |

| 底個 [ti kai] | ||

| where | 底塊 [ti ko] | |

| when | 珍時 [tiaŋ si] | |

| how | manner | 做呢 [tso ni] |

| state | 在些(樣) [tsai sẽ ĩõ] | |

| 乜些樣 [miʔ sẽ ĩõ] | ||

| 什乜樣 [si miʔ ĩõ] | ||

| how many | 幾 + CL + N [kui] | |

| 若多 + (CL) + (N) [dzieʔ tsoi] | ||

| how much | 若多 [dzieʔ tsoi] | |

| why | 做呢 [tso ni] | |

Numerals

| Pronunciation | Financial | Normal | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| liŋ5 | 零 | 〇 | 0 | 〇 is an informal way to represent zero, but 零 is more commonly used, especially in schools. also 空 [kang3] |

| tsek8 | 壹 | 一 | 1 | also 蜀 [tsek8] (original character) also 弌 (obsolete) also [ik4] as the last digit of a 2-or-more-digit number e.g. 二十一 [dzi6 tsap8 ik4] or days of a month e.g. 一號 [ik4 ho7] or as an ordinal number e.g. 第一 [tõĩ6 ik4] also 么(T) or 幺(S) [iou1] when used in phone numbers etc. |

| no6 | 兩(T) | 二 | 2 | also 弍 (obsolete) also 貳(T) also [dzi6] as the last digit of a 2-or-more-digit number e.g. 三十二 [sã1 tsap8 dzi6] or days of a month e.g. 二號 [dzi6 ho7] or as an ordinal number e.g. 第二 [tõĩ6 dzi6]. |

| sã1 | 叄(T) | 三 | 3 | also 弎 (obsolete) also 參 [sã1]. |

| si3 | 肆 | 四 | 4 | |

| ŋou6 | 伍 | 五 | 5 | |

| lak8 | 陸 | 六 | 6 | |

| tsʰik4 | 柒 | 七 | 7 | |

| poiʔ4 | 捌 | 八 | 8 | |

| kau2 | 玖 | 九 | 9 | |

| tsap8 | 拾 | 十 | 10 | Although some people use 什, It is not acceptable because it can be written over into 伍. |

Note: (T): Traditional characters; (S): Simplified characters.

Ordinal numbers are formed by adding 第 [tõĩ˧˥] in front of a cardinal number.

Voice

In Teochew passive construction, the agent phrase by somebody always has to be present, and is introduced by either 乞 [kʰoiʔ˦] (some speakers use [kʰəʔ] or [kʰiəʔ] instead) or 分 [puŋ˧], even though it is in fact a zero or indefinite agent as in:

- 伊分人刣掉。

- [i˧ puŋ˧ naŋ˥ tʰai˥ tiou˩]

- S/he was killed (by someone).

While in Mandarin one can have the agent introducer 被; bèi or 給; gěi alone without the agent itself, it is not grammatical to say

- * 個杯分敲掉。

- [kai˥ pue˧ puŋ˧ kʰa˧ tiou˩]

- The cup was broken.

- cf. Mandarin 杯子給打破了; bēizi gěi dǎ pòle)

Instead, we have to say:

- 個杯分人敲掉。

- [kai˥ pue˧ puŋ˧ naŋ˥ kʰa˧ tiou˩]

- The cup was broken.

Even though this 人 [naŋ˥] is unknown.

Note also that the agent phrase 分人 [puŋ˧ naŋ˥] always comes immediately after the subject, not at the end of the sentence or between the auxiliary and the past participle like in some European languages (e.g. German, Dutch)

Comparison

Comparative construction with two or more nouns

Teochew uses the construction "X ADJ 過 [kue˨˩˧] Y", which is believed to have evolved from the Old Chinese "X ADJ 于 (yú) Y" structure to express the idea of comparison:

- 伊雅過汝。

- [i˧ ŋia˥˨ kue˨˩˧ lɨ˥˨]

- She is more beautiful than you.

Cantonese uses the same construction:

- 佢靚過你。

- Keoi5 leng3 gwo3 nei5.

- She is more beautiful than you.

However, due to modern influences from Mandarin, the Mandarin structure "X 比 Y ADJ" has also gained popularity over the years. Therefore, the same sentence can be re-structured and becomes:

- 伊比汝雅。

- [i˩ pi˥˨ lɨ˥˨ ŋia˥˨]

- She is more beautiful than you.

- cf. Mandarin 她比你漂亮; tā bǐ nǐ piàoliang

Comparative construction with only one noun

It must be noted that the 過- or 比-construction must involve two or more nouns to be compared; an ill-formed sentence will be yielded when only one is being mentioned:

- * 伊雅過 (?)

Teochew is different from English, where the second noun being compared can be left out ("Tatyana is more beautiful (than Lisa)". In cases like this, the 夭-construction must be used instead:

- 伊夭雅。

- [i1 iou6 ŋia2]

- She is more beautiful.

The same holds true for Mandarin and Cantonese in that another structure needs to be used when only one of the nouns being compared is mentioned. Note also that Teochew and Mandarin both use a pre-modifier (before the adjective) while Cantonese uses a post-modifier (after the adjective).

- Mandarin

- 她比較漂亮

- tā bǐjiào piàoliang

- Cantonese

- 佢靚啲

- keoi5 leng3 di1

There are two words which are intrinsically comparative in meaning, i.e. 贏 [ĩã5] "better" and 輸 [su1] "worse". They can be used alone or in conjunction with the 過-structure:

- 只領裙輸(過)許領。

- [tsi2 nĩã2 kuŋ5 su1 kue3 hɨ2 nĩã2]

- This skirt is not as good as that one.

- 我內個電腦贏伊個好多。

- [ua2 lai6 kai7 tiaŋ6 nau2 ĩã5 i1 kai7 hoʔ2 tsoi7]

- My computer (at home) is far better than his.

Note the use of the adverbial 好多 [hoʔ2 tsoi7] at the end of the sentence to express a higher degree.

Equal construction

In Teochew, the idea of equality is expressed with the word 平 [pẽ5] or 平樣 [pẽ5 ĩõ7]:

- 只本書佮許本平重。

- [tsi2 puŋ2 tsɨ1 kaʔ4 hɨ2 puŋ2 pẽ5 taŋ6]

- This book is as heavy as that one.

- 伊兩人平平樣。

- [i1 no6 naŋ5 pẽ5 pẽ5 ĩõ7]

- They are the same. (They look the same./They're as good as each other./They're as bad as each other.)

- Lit. The two people are the same same way.

Superlative construction

To express the superlative, Teochew uses the adverb 上 [siaŋ5] or 上頂 [siaŋ5 teŋ2]. However, it should be noted that 上頂 is usually used with a complimentary connotation.

- 只間物上頂好食。

- [tsi2 kõĩ1 mueʔ8 siaŋ5 teŋ2 ho2 tsiaʔ8]

- This (restaurant) is (absolutely) the most delicious.

- 伊人對我上好。

- [i1 naŋ5 tui3 ua2 siaŋ5 ho2]

- They treat me best.

- Lit. The people treat me very well.

Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Teochew shares a lot of similarities with Cantonese because of their continuous contact with each other. Like Cantonese, Teochew has a great deal of monosyllabic words. However, ever since the standardisation of Modern Standard Chinese, Teochew has absorbed a lot of Putonghua vocabulary, which is predominantly polysyllabic. Also, Teochew varieties in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia have also borrowed extensively from Malay.

Archaic vocabulary

Teochew and other Southern Min varieties, such as Taiwanese Hokkien, preserve a good deal of Old Chinese vocabulary, such as 目 [mak] eye (Chinese: 眼睛; pinyin: yǎnjīng, Taiwanese Hokkien: 目 ba̍k), 灱 [ta] dry (Chinese: 乾; pinyin: gān, Taiwanese Hokkien: 焦 ta), and 囥 [kʰəŋ] hide (cf. Chinese: 藏; pinyin: cáng; Taiwanese Hokkien: 囥 khǹg).

Romanisation

Teochew was romanised by the Provincial Education Department of Guangdong in 1960 to aid linguistic studies and the publication of dictionaries, although Pe̍h-ōe-jī can also be used because Christian missionaries invented it for the transcription of varieties of Southern Min.

Initials

Initial consonants of Teochew, are represented in the Guangdong Romanization system as: B, BH, C, D, G, GH, H, K, L, M, N, NG, P, R, S, T, and Z.

Examples:

- B [p] - bag (北 north)

- Bh [b]- bhê (馬 horse)

- C [tsʰ] - cên (青 green), cǔi (嘴 mouth), cêng (槍 gun)

- D [t] - dio (潮 tide)

- G [k] - gio (橋 bridge)

- GH [g] - gho (鵝 goose)

- H [h] - hung (雲 cloud)

- K [kʰ] - ke (走 to go)

- L [l] - lag (六 six)

- M [m] - mêng (明 bright)

- N [n] - nang (人 person)

- NG [ŋ] - ngou (五 five)

- P [pʰ] - peng (平 peace)

- R [(d)z] - riêg/ruah (熱 hot)

- S [s] - sên (生 to be born)

- T [tʰ] - tin (天 sky)

- Z [ts] - ziu (州 region/state)

Finals

Vowels

Vowels and vowel combinations in the Teochew dialect include: A, E, Ê, I, O, U, AI, AO, IA, IAO, IO, IU, OI, OU, UA, UAI, UE, and UI.

Examples:

- A - ma (媽 mother)

- E - de (箸 chopsticks)

- Ê - sên (生 to be born)

- I - bhi (味 smell/taste)

- O - to (桃 peach)

- U - ghu (牛 cow)

Many words in Teochew are nasalized. This is represented by the letter "n" in the Guangdong Pengim system.

Example (nasalized):

- suan (山 mountain)

- cên (青 green)

Ending

Ending consonants in Teochew include M and NG as well as the stops discussed below.

Examples:

- M - iam (鹽 salt)

- NG - bhuang (萬 ten thousand)

Teochew retains many consonant stops lost in Mandarin. These stops include a labial stop: "b"; velar stop: "g"; and glottal stop: "h".

Examples:

- B - zab (十 ten)

- G - hog (福 happiness)

- H - tih (鐵 iron)

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Teochew". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Chaozhou". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Chaoshan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ baike.baidu.com/view/39085.htm Accessed 2015-06-01

- ↑ Nominalization in Asian Languages: Diachronic and typological perspectives, p. 11, Yap, FoongHa; Grunow-Hårsta, Karen; Wrona, Janick (ed.) John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2011

Sources

- Beijing da xue Zhongguo yu yan wen xue xi yu yan xue jiao yan shi. (2003). Han yu fang yin zi hui. (Chinese dialectal vocabulary) Beijing: Yu wen chu ban she (北京大學中國語言文學系語言學教研室, 2003. 漢語方音字彙. 北京: 語文出版社) ISBN 7-80184-034-8

- Cai Junming. (1991). Putonghua dui zhao Chaozhou fang yan ci hui. (Chaozhou dialectal vocabulary, contrasted with Mandarin) Hong Kong: T. T. Ng Chinese Language Research Centre (蔡俊明, 1991. 普通話對照潮州方言詞彙. 香港: 香港中文大學吳多泰中國語文研究中心) ISBN 962-7330-02-7

- Chappell, Hilary (ed.) (2001). Sinitic grammar : synchronic and diachronic perspectives. Oxford; New York: OUP ISBN 0-19-829977-X

- Chen, Matthew Y. (2000). Tone Sandhi: patterns across Chinese dialects. Cambridge, England: CUP ISBN 0-521-65272-3

- DeFrancis, John. (1984). The Chinese language: fact and fantasy. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press ISBN 0-8248-1068-6

- Li, Xin Kui. (1994). Guangdong di fang yan. (Dialects of Guangdong) Guangzhou, China: Guangdong ren min chu ban she (李新魁, 1994. 廣東的方言. 廣州: 廣東 人民出版社) ISBN 7-218-00960-3

- Li, Yongming. (1959). Chaozhou fang yan. (Chaozhou dialect) Beijing: Zhonghua. (李永明, 1959. 潮州方言. 北京: 中華)

- Lin, Lun Lun. (1997). Xin bian Chaozhou yin zi dian. (New Chaozhou pronunciation dictionary) Shantou, China: Shantou da xue chu ban she. (林倫倫, 1997. 新編潮州音字典. 汕頭: 汕頭大學出版社) ISBN 7-81036-189-9

- Norman, Jerry. [1988] (2002). Chinese. Cambridge, England: CUP ISBN 0-521-29653-6

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1986). Languages of China. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-06694-9

- Yap, FoongHa; Grunow-Hårsta, Karen; Wrona, Janick (ed.) (2011). "Nominalization in Asian Languages: Diachronic and typological perspectives". Hong Kong Polytechnic University /Oxford University : John Benjamins Publishing Company ISBN 978-9027206770

Further reading

Works on the Teochew dialect

- Josiah Goddard (1883). A Chinese and English vocabulary: in the Tie-chiu dialect (2 ed.). Shanghai: American Presbyterian Mission Press. p. 237. Retrieved 10 February 2012. (the New York Public Library) (digitized April 2, 2008)

Bibles in the Teochew dialect

- Kū-ieh sàn-bú-zṳ́ ē-kńg tshûan-tsṳ e̍k-tsò tiê-chiu pe̍h-ūe. Swatow: printed for the British and Foreign Bible Society at the English Presbyterian Mission Press. 1898. Retrieved 10 February 2012. (11 Samuel. (Tie-chiu dialect.)) (Harvard University) (digitized December 17, 2007)

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Teochew phrasebook. |

- Database of Pronunciations of Chinese Dialects (in English, Chinese and Japanese)

- Teochew People - Teochew dialect (in Chinese)

- Diojiu Bhung Gak

- Gaginang

- Glossika - Chinese Languages and Dialects

- Mogher (in Chinese, English and French)

- Omniglot

- Shantou University Chaozhou Studies Resources (in Chinese)

- Teochew Web (in Chinese and English)

- Tonal harmony and register contour in Chaozhou

- Teochew Federation Singapore