Shanghainese

| Shanghainese | |

|---|---|

|

上海話 / 上海话 Zaanhehho 上海閒話 / 上海闲话 Zaanheh-hehho 滬語 / 沪语 Hu nyy | |

| Pronunciation | [z̥ɑ̃̀héɦɛ̀ɦʊ̀], [ɦùɲý] |

| Native to | China, overseas communities |

| Region | City of Shanghai and surrounding Yangtze River Delta |

| Ethnicity | Shanghainese people |

Native speakers | 10–14 million (2013) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 |

suji |

wuu-sha | |

| Glottolog |

shan1293 Shanghainese[1] |

| Linguasphere |

79-AAA-dbb > |

| Shanghainese | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 上海话 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 上海話 | ||||||||||

| Shanghainese Romanization |

Zaanhehho [z̥ɑ̃̀héɦʊ̀] | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Shanghai language | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Shanghainese | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 上海闲话 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 上海閒話 | ||||||||||

| Shanghainese Romanization |

Shanghe Hhehho [z̥ɑ̃̀hé ɦɛ̀ɦʊ̀] | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Shanghai speech | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Hu language | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 沪语 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 滬語 | ||||||||||

| Shanghainese Romanization | [ɦuɲy] | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Hu (Shanghai) language | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

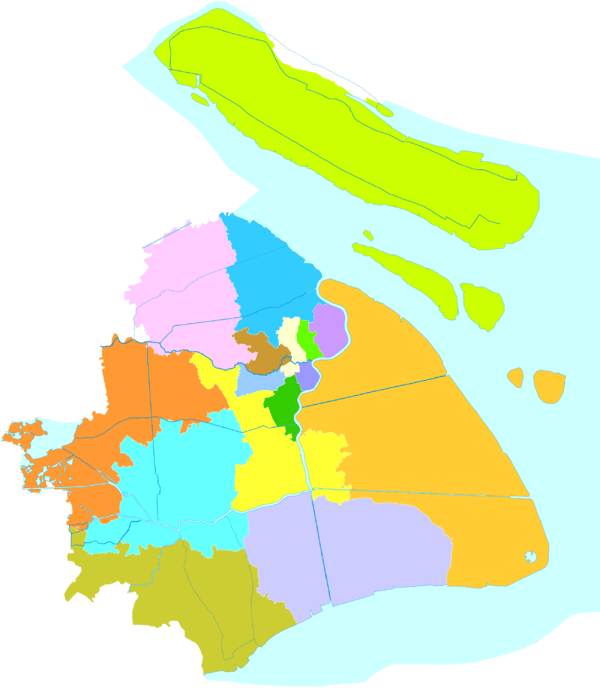

The Shanghainese language, also known as the Shanghai dialect, Hu language or Hu dialect, is a variety of Wu Chinese spoken in the central districts of the City of Shanghai and its surrounding areas. It is classified as part of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Shanghainese, like other Wu variants, is mutually unintelligible with other varieties of Chinese, such as Mandarin.[2]

Shanghainese belongs to the Taihu Wu subgroup, and contains vocabulary and expressions from the entire Taihu Wu area of southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang. With nearly 14 million speakers, Shanghainese is also the largest single form of Wu Chinese. It serves as the lingua franca of the entire Yangtze River Delta region.

Shanghainese is rich in vowels [i y ɪ ʏ ei ø ɛ ə ɐ a ɑ ɔ ɤɯ o ʊ u] (twelve of which are phonemic) and in consonants. Like other Taihu Wu dialects, Shanghainese has voiced initials [b d ɡ ɦ z v dʑ ʑ]: neither Cantonese nor Mandarin has voiced initial stops or affricates. The Shanghainese tonal system is also significantly different from other Chinese varieties, sharing more similarities with the Japanese pitch accent, with two level tonal contrasts (high and low), whereas Cantonese and Mandarin are typical of contour tonal languages.

History

Shanghai did not become a regional center of commerce until it was opened to foreign investment during the late Qing dynasty. Consequently, languages and dialects spoken around Shanghai had long been subordinate to those spoken around Jiaxing and later Suzhounese. In the late 19th century, most vocabulary of the Shanghai area had been a hybrid between Southern Jiangsu and Ningbonese.[3] Since the 1850s, owing to the growth of Shanghai's economy, Shanghainese has become one of the fastest-developing languages of the Wu Chinese subgroup, undergoing rapid changes and quickly replacing Suzhounese as the prestige dialect of the Yangtze River Delta region. It underwent sustained growth that reached a hiatus in the 1930s during the Republican era, when migrants arrived in Shanghai and immersed themselves in the local tongue.

After 1949, the government imposed Mandarin (Putonghua) as the official language of the whole nation of China. The dominance and influence of Shanghainese began to wane slightly. Since Chinese economic reform began in 1978, especially, Shanghai became home to a great number of migrants from all over the country. Due to the national prominence of Mandarin, learning Shanghainese was no longer necessary for migrants, because those educated after the 1950s could generally communicate in Mandarin. However, Shanghainese remained a vital part of the city's culture and retained its prestige status within the local population. In the 1990s, it was still common for local radio and television broadcasts to be in Shanghainese. In 1995, the TV series Sinful Debt featured extensive Shanghainese dialogue; when it was broadcast outside Shanghai (mainly in adjacent Wu-speaking provinces) Mandarin subtitles were added. The Shanghainese TV series Lao Niang Jiu (Old Uncle) was broadcast from 1995 to 2007 [4] and was popular among Shanghainese residents. Shanghainese programming has since slowly declined amid regionalist/localist accusations.

From 1992 onward, Shanghainese use was discouraged in schools,[5] and many children native to Shanghai can no longer speak Shanghainese.[6] In addition, Shanghai's emergence as a cosmopolitan global city consolidated the status of Mandarin as the standard language of business and services, at the expense of the local language.[3]

Since 2005, new movements have emerged to protect Shanghainese from fading away. At municipal legislative discussions in 2005, former Shanghai opera actress Ma Lili moved to "protect" the language, stating that she was one of the few remaining Shanghai opera actresses who still retained authentic classic Shanghainese pronunciation in their performances. Shanghai's former party boss Chen Liangyu, a native Shanghainese himself, reportedly supported her proposal.[3] There have been talks of re-integrating Shanghainese into pre-kindergarten education, because many children are unable to speak any Shanghainese. A citywide program was introduced by the city government's language committee in 2006 to record native speakers of different Shanghainese varieties for archival purposes and, by 2010, many Shanghainese-language programs were running.[7]

The Shanghai government has begun to reverse its course and seek fluent speakers of authentic Shanghainese, but only two out of thirteen recruitment stations have found Traditional Shanghainese speakers; the rest of the 14 million people of Shanghai speak modern Shanghainese, and it has been predicted that local variants will be wiped out. Professor Qian Nairong is working on efforts to save the language.[8][9] In response to criticism, Qian reminds people that Shanghainese was once fashionable, saying, "the popularization of Mandarin doesn't equal the ban of dialects. It doesn't make Mandarin a more civilized language either. Promoting dialects is not a narrow-minded localism, as it has been labeled by some netizens".[10] The singer and composer Eheart Chen sings many of his songs in Shanghainese instead of Mandarin to preserve the language.[11]

Since 2006, the Modern Baby Kindergarten in Shanghai has prohibited all of its students from speaking anything but Shanghainese on Fridays to preserve the language amongst younger speakers.[12][13] In 2011, Professor Qian said that the sole remaining speakers of real Shanghainese are a group of Shanghainese peoples over the age of 60 and native citizens who have little outside contact, and he strongly urges that Shanghainese be taught in the regular school system from kindergarten all the way to elementary, saying it is the only way to save Shanghainese, and that attempts to introduce it in university courses and operas are not enough.[14]

Fourteen native Shanghainese speakers had audio recordings made of their Shanghainese on May 31, 2011. They were selected based on accent purity, way of pronunciation and other factors.[15]

Intelligibility and variations

Shanghainese is not mutually intelligible with any language or dialect of Mandarin. It is around 50% intelligible (with 28.9% lexical similarity) with the Mandarin, heard in Beijing. Modern Shanghainese, however, has been heavily influenced by modern Mandarin and other Chinese languages, such as Cantonese. That makes the Shanghainese spoken by young people in the city different, sometimes significantly, from that spoken by the older population and also that inserting Mandarin, Cantonese or both into Shanghainese sentences during everyday conversation is very common, at least for young people. Like most subdivisions of Chinese, it is easier for a local speaker to understand Mandarin than it is for a Mandarin speaker to understand the local language.

Shanghainese is part of the larger Wu subgroup of Chinese languages. It is somewhat similar to the speech of neighboring cities of Ningbo and Suzhou. People mingling between those areas do not need to code-switch to Mandarin when they speak to each other. However, there are noticeable tonal and phonological changes, which do not impede intelligibility. As the dialect continuum of Wu continues to further distances, however, significant changes occur in phonology and lexicon to the point that it is no longer possible to converse intelligibly. Most Shanghainese speakers find that by Wuxi, differences become significant and that the Wuxi dialect would take weeks to months for a Shanghainese-speaker to learn fully. Similarly, Hangzhou dialect is understood by most Shanghainese-speakers, but it is considered "rougher" and does not have as much glide and flow in comparison. The language evolved in and around Taizhou, Zhejiang, where it becomes difficult for a Shanghainese speaker to comprehend. Wenzhounese, spoken in the southernmost part of Zhejiang province, is considered part of the Wu group but mutually unintelligible with Shanghainese.

Shanghainese-speakers also cannot understand Cantonese, Southern Min (such as Hokkien-Taiwanese), and any other language in any other group of Chinese.

Phonology

Following conventions of Chinese syllable structure, Shanghainese syllables can be divided into initials and finals. The initial occupies the first part of the syllable. The final occupies the second part of the syllable and can be divided further into an optional medial and an obligatory rime (sometimes spelled rhyme). Tone is also a feature of the syllable in Shanghainese.[16]:6–16 Syllabic tone, which is typical to the other Sinitic languages, has largely become verbal tone in Shanghainese.

Initials

| Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | tenuis | p | t̪ | k | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | t̪ʰ | kʰ | |||

| voiced | b | d̪ | ɡ | |||

| Affricate | tenuis | t͡s | t͡ɕ | |||

| aspirated | t͡sʰ | t͡ɕʰ | ||||

| voiced | d͡ʑ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɕ | h | |

| voiced | v | z | ʑ | ɦ | ||

| Lateral | l | |||||

Shanghainese has a set of tenuis, voiceless aspirated and voiced plosives and affricates, as well as a set of voiceless and voiced fricatives. Alveolo-palatal initials are also present in Shanghainese.

Voiced stops are phonetically voiceless with slack voice phonation in stressed, word initial position.[17] This phonation (often referred to as murmur) also occurs in zero onset syllables, syllables beginning with fricatives, and syllables beginning with sonorants. These consonants are true voiced in intervocalic position.[18]

Finals

The table below lists the vowel nuclei of Shanghainese[19]

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | |||

| Close | /i/ | /y/ | /u, o/ | |

| Mid | /ɛ/ | /ø/ | /ə/ | /ɔ/ |

| Open | /a/ | /ɑ/ | ||

| Diphthong | /ei, ɤɯ/ | |||

The following chart lists all possible finals (medial + nucleus + coda) in Shanghainese represented in IPA.[20][16]:11

| Coda | Open | Nasal | Glottal stop | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial | ∅ | j | w | ∅ | j | w | ∅ | j | w | |

| Nucleus | u | u | ||||||||

| i | i | |||||||||

| o | o | |||||||||

| y | y | |||||||||

| ei | ei | wei | ||||||||

| ɤɯ | ɤɯ | jɤɯ | ||||||||

| ə | əŋ | wəŋ | əʔ | wəʔ | ||||||

| ɛ | ɛ | jɛ | wɛ | ɪɲ | ɪʔ | |||||

| ɔ | ɔ | jɔ | ʊŋ | jʊŋ | ʊʔ | jʊʔ | ||||

| ø | ø | jø | wø | ʏɲ | ʏʔ | |||||

| a | a | ja | wa | ã | jã | wã | ɐʔ | jɐʔ | wɐʔ | |

| ɑ | ɑ̃ | jɑ̃ | wɑ̃ | |||||||

- Syllabic continuants: [z̩] [m̩] [ŋ̩] [ɚ]

The transcriptions used above are broad and the following points are of note when pertaining to actual pronunciation:[19]

- [u] and [o] are pronounced with similar tongue position, but the former is pronounced with compressed lip rounding while the latter is pronounced with protruded lip rounding ([ɯ̽ᵝ] and [ʊ] respectively).

- The vowel pairs [a, ɐ], [ɛ, ɪ], [ɔ, ʊ] and [ø, ʏ] are each pronounced nearly identically ([ɐ], [e], [o̞] and [ø] respectively) despite having different conventional transcriptions.

- /j/ is pronounced [ɥ] before rounded vowels.

The Middle Chinese [-ŋ] rimes are retained, while [-n] and [-m] are either retained or have disappeared in Shanghainese. Middle Chinese [-p -t -k] rimes have become glottal stops, [-ʔ].[21]

Tones

Shanghainese has five phonetically distinguishable tones for single syllables said in isolation. These tones are illustrated below in Chao tone names. In terms of Middle Chinese tone designations, the yin tone category has three tones (yinshang and yinqu tones have merged into one tone), while the yang category has two tones (the yangping, yangshang, and yangqu have merged into one tone).[22][16]:17

| Ping (平) | Shang (上) | Qu (去) | Ru (入) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yin (阴) | 52 (T1) | 34 (T2) | 44ʔ (T4) | |

| Yang (阳) | 14 (T3) | 24ʔ (T5) | ||

The conditioning factors which led to the yin–yang split still exist in Shanghainese, as they do in other Wu dialects: yang tones are only found with voiced initials [b d ɡ z v dʑ ʑ m n ɲ ŋ l ɦ], while the yin tones are only found with voiceless initials.

The ru tones are abrupt, and describe those rimes which end in a glottal stop /ʔ/. That is, both the yin–yang distinction and the ru tones are allophonic (dependent on syllabic structure). Shanghainese has only a two-way phonemic tone contrast,[23] falling vs rising, and then only in open syllables with voiceless initials.

Tone sandhi

Tone sandhi is a process whereby adjacent tones undergo dramatic alteration in connected speech. Similar to other Northern Wu dialects, Shanghainese is characterized by two forms of tone sandhi: a word tone sandhi and a phrasal tone sandhi.

Word tone sandhi in Shanghainese can be described as left-prominent and is characterized by a dominance of the first syllable over the contour of the entire tone domain. As a result, the underlying tones of syllables other than the leftmost syllable, have no effect on the tone contour of the domain. The pattern is generally described as tone spreading (T1-4) or tone shifting (T5, except for 4- and 5-syllable compounds, which can undergo spreading or shifting). The table below illustrates possible tone combinations.

| Tone | One syllable | Two syllables | Three syllables | Four syllables | Five syllables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 52 | 55 22 | 55 44 22 | 55 44 33 22 | 55 44 33 33 22 |

| T2 | 34 | 33 44 | 33 44 22 | 33 44 33 22 | 33 44 33 33 22 |

| T3 | 14 | 11 44 | 11 44 11 | 11 44 33 11 | 11 44 33 22 11 |

| T4 | 44 | 33 44 | 33 44 22 | 33 44 33 22 | 33 44 33 22 22 |

| T5 | 24 | 11 24 | 11 11 24 | 11 22 22 24 22 44 33 11 |

11 11 11 11 24 22 44 33 22 11 |

As an example, in isolation, the two syllables of the word for China are pronounced with T1 and T4: /tsʊŋ52/ and /kwəʔ44/. However, when pronounced in combination, T1 from /tsʊŋ/ spreads over the compound resulting in the following pattern /tsʊŋ55kwəʔ22/. Similarly, the syllables in a common expression for foolish have the following underlying phonemic and tonal representations: /zəʔ24/ (T5), /sɛ52/ (T1), and /ti34/ (T2). However, the syllables in combination exhibit the T5 shifting pattern where the first-syllable T5 shifts to the last syllable in the domain: /zəʔ11sɛ11ti24/.[16]:38–46

Phrasal tone sandhi in Shanghainese can be described as right-prominent and is characterized by a right syllable retaining its underlying tone and a left syllable receiving a mid-level tone based on the underlying tone's register. The table below indicates possible left syllable tones in right-prominent compounds.[16]:46–47

| Tone | Underlying Tone | Neutralized Tone |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 52 | 44 |

| T2 | 34 | 44 |

| T3 | 14 | 33 |

| T4 | 44 | 44 |

| T5 | 24 | 22 |

For instance, when combined, /ma14/ and /tɕjɤɯ34/ become /ma33tɕjɤɯ34/ (buy wine).

Sometimes meaning can change based on whether left-prominent or right-prominent sandhi is used. For example, /tsʰɔ34/ and /mi14/ when pronounced /tsʰɔ33mi44/ (i.e., with left-prominent sandhi) means fried noodles. When pronounced /tsʰɔ44mi14/ (i.e., with right-prominent sandhi), it means to fry noodles.[16]:35

Common words and phrases

Note: Chinese characters for Shanghainese are not standardized and are provided for reference only. IPA transcription is for the Middle Period of modern Shanghainese (中派上海话), pronunciation of those between 20 and 60 years old.

| Translation | IPA | Chinese character Transliteration |

|---|---|---|

| Shanghainese (language) | [zɑ̃.hɛ ɦɛ.ɦo] | 上海闲话 or 上海言话(上海閒話 or 上海言話) |

| Shanghainese (people) | [zɑ̃.hɛ.ɲɪɲ] | 上海人 |

| I | [ŋu] | 我、吾 |

| we or I | [ɐʔ.la] | 阿拉) |

| he/she | [ɦi] | 渠(佢, 伊, 其) |

| they | [ɦi.la] | 渠拉(佢拉, 伊拉) |

| you (sing.) | [nʊŋ] | 侬(儂) |

| you (plural) | [na] | 倷 (modern Mandarin-based approximation: 㑚) |

| hello | [nʊŋ.hɔ] | 侬好(儂好) |

| good-bye | [tsɛ.ɦwei] | 再会(再會) |

| thank you | [ʑja.ja.nʊŋ] or [ʑja.ʑja.nʊŋ] | 谢谢侬(謝謝儂) |

| sorry | [tei.vəʔ.tɕʰi] | 对勿起(對勿起) |

| but, however | [dɛ.z̩], [dɛ.z̩.ni] | 但是, 但是呢 |

| please | [tɕʰɪɲ] | 请(請) |

| that one | [ɛ.tsa], [i.tsa] | 埃只, 伊只(埃隻, 伊隻) |

| this one | [ɡəʔ.tsa] | 箇只(箇隻) |

| there | [ɛ.ta], [i.ta] | 埃𡍲, 伊𡍲 |

| over there | [ɛ.mi.ta], [i.mi.ta] | 埃面𡍲, 伊面𡍲 |

| here | [ɡəʔ.ta] | 搿𡍲 |

| to have | [ɦjɤɯ.təʔ] | 有得 |

| to exist, here, present | [lɐʔ.hɛ] | 徕許, 勒許 |

| now, current | [ɦi.zɛ] | 现在(現在) |

| what time is it? | [ɦi.zɛ tɕi.ti tsʊŋ] | 现在几点钟?(現在幾點鐘?) |

| where | [ɦa.li.ta], [sa.di.fɑ̃] | 何里𡍲(何裏𡍲), 啥地方 |

| what | [sa.ɦəʔ] | 啥个 |

| who | [sa.ɲɪɲ] or [ɦa.li.ɦwei] | 啥人, 何里位 |

| why | [ɦwei.sa] | 为啥(為啥) |

| when | [sa.zən.kwɑ̃] | 啥辰光 |

| how | [na.nən], [na.nən.ka] | 哪能 (哪恁), 哪能介 (哪恁介) |

| how much? | [tɕi.di] | 几钿?(幾鈿?) |

| yes | [ɛ] | 哎 |

| no | [m̩], [vəʔ.z̩], [m̩.məʔ], [vjɔ] | 呒, 勿是, 呒没, 覅(嘸, 勿是, 嘸沒, 覅) |

| telephone number | [di.ɦo ɦɔ.dɤɯ] | 电话号头(電話號頭) |

| home | [ʊʔ.li] | 屋里(屋裏) |

| Come to our house and play. | [tɔ ɐʔ.la ʊʔ.li.ɕjɑ̃ lɛ bəʔ.ɕjɐ̃] | 到阿拉屋里向来孛相(白相)!(到阿拉屋裏向來孛相!) |

| Where's the restroom? | [da.sɤɯ.kɛ ləʔ.ləʔ ɦa.li.ta] | 汏手间勒勒何里𡍲?(汏手間勒勒何裏𡍲?) |

| Have you eaten dinner? | [ɦja.vɛ tɕʰɪʔ.ku.ləʔ va] | 夜饭吃过了𠲎?(夜飯喫過了𠲎?) |

| I don't know | [ŋu vəʔ.ɕjɔ.təʔ] | 我勿晓得.(我勿曉得.) |

| Do you speak English? | [nʊŋ ɪɲ.vən kɑ̃.təʔ.lɛ va] | 侬英文讲得来𠲎?(儂英文講得來𠲎?) |

| I adore you | [ŋu ɛ.mu nʊŋ] | 我爱慕侬.(我愛慕儂!) |

| I like you a lot | [ŋu lɔ hwø.ɕi nʊŋ əʔ] | 我老欢喜侬个!(我老歡喜儂个) |

| news | [ɕɪɲ.vən] | 新闻(新聞) |

| dead | [ɕi.tʰəʔ.ləʔ] | 死脱了 |

| alive | [ɦwəʔ.ləʔ.hɛ] | 活勒嗨(活着) |

| a lot | [tɕjɔ.kwɛ] | 交关 |

| inside, within | [li.ɕjɑ̃] | 里向 |

| outside | [ŋa.dɤɯ] | 外頭 |

| How are you? | [nʊŋ hɔ va] | 侬好𠲎?(儂好𠲎?) |

Literary and vernacular pronunciations

| 字 | Pinyin | English translation | Literary | Vernacular |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 家 | jiā | house | tɕia˥˨ | ka˥˨ |

| 顏 | yán | face | ɦiɪ˩˩˧ | ŋʱɛ˩˩˧ |

| 櫻 | yīng | cherry | ʔiŋ˥˨ | ʔɐ̃˥˨ |

| 孝 | xiào | filial piety | ɕiɔ˧˧˥ | hɔ˧˧˥ |

| 學 | xué | learning | ʱjɐʔ˨ | ʱʊʔ˨ |

| 物 | wù | thing | vəʔ˨ | mʱəʔ˨ |

| 網 | wǎng | web | ʱwɑŋ˩˩˧ | mʱɑŋ˩˩˧ |

| 鳳 | fèng | male phoenix | voŋ˩˩˧ | boŋ˩˩˧ |

| 肥 | féi | fat | vi˩˩˧ | bi˩˩˧ |

| 日 | rì | sun | zəʔ˨ | ɲʱiɪʔ˨ |

| 人 | rén | person | zən˩˩˧ | ɲʱin˩˩˧ |

| 鳥 | niǎo | bird | ʔɲiɔ˧˧˥ | tiɔ˧˧˥ |

Plural pronouns

The first-person pronoun is suffixed with 伲 [ɲi˨˧] as in "我伲" [ŋu˨˨.ɲi˦˦], and third-person with 拉 [la˥˧]), but the second-person plural is a separate root, 㑚 [nʌ˨˧].[24]

Writing

Chinese characters are used to write Shanghainese. Romanization of Shanghainese was first developed by Protestant English and American Christian missionaries in the 19th century, including Joseph Edkins.[25] Usage of this romanization system was mainly confined to translated Bibles for use by native Shanghainese, or English-Shanghainese dictionaries, some of which also contained characters, for foreign missionaries to learn Shanghainese. A system of phonetic symbols similar to Chinese characters called "New Phonetic Character" were also developed by in the 19th century by American missionary Tarleton Perry Crawford.[26]

Shanghainese is sometimes written informally using homophones: "lemon" (ningmeng), written 檸檬 in Standard Chinese, may be written 人門 (person-door) in Shanghainese; and "yellow" (huang黄) may be written 王 (king) rather than standard 黃. These are not homophones in Mandarin, but are homophones in Shanghainese. There are also some homophones in Mandarin which are not homophonic in Shanghainese, e.g. 做, 作 and 坐.[27]

Protestant missionaries in the 1800s created the Shanghainese Phonetic Symbols to write Shanghainese phonetically. The symbols are a syllabary similar to the Japanese Kana system. The system has not been used and is only seen in a few historical books.[28][29]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Shanghainese". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Chinese languages". britannica.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018.

- 1 2 3 China Newsweek Archived March 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chinese Wikipedia page of Lao Niang Jiu 老娘舅, Wikipedia .

- ↑ Yin Yeping (July 31, 2011). "60 years of Putonghua and English drown out local tongues". Global Times. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013.

- ↑ Zat Liu (August 20, 2010). "Is Shanghai's local dialect, and culture, in crisis?". CNN GO. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Call goes out: Language, please". Shanghai Daily. April 6, 2010. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Shanghai struggles to save disappearing dialect". CNN GO. November 22, 2010. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- ↑ Tiffany Ap (November 18, 2010). "That ain't Shanghainese you're speaking". shanghaiist. Archived from the original on March 28, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ↑ Tracy You (June 3, 2010). "Word wizard: The man bringing Shanghainese back to the people". CNN GO. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- ↑ Tracy You (July 26, 2010). "Eheart Chen: Shanghai's modern rocker with a nostalgic soul". CNN GO. Archived from the original on July 31, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- ↑ Ni Dandan (May 16, 2011). "Dialect faces death threat". Global Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

we arranged Shanghai Day on Fridays to promote the language and local culture

- ↑ Jia Feishang (May 13, 2011). "Stopping the local dialect becoming derelict". Shanghai Daily. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ↑ Miranda Shek (February 2, 2011). "Local dialect in danger of vanishing". Global Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ↑ Liang Yiwen (May 30, 2011). "14 Shanghainese selected for dialect recording". Shanghai Daily. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Zhu, Xiaonong (2006). A Grammar of Shanghai Wu. Lincom.

- ↑ Ladefoged, Peter, Maddieson, Ian. The Sounds of the World's Languages. Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, p. 64-66.

- ↑ Zhu, Xiaonong S. Shanghai Tonetics. Lincom Europa, 1999, p. 12.

- 1 2 Chen & Gussenhoven (2015)

- ↑ Zhu, Xiaonong S. Shanghai Tonetics. Lincom Europa, 1999, p. 14-17.

- ↑ Svantesson, Jan-Olof. "Shanghai Vowels," Lund University, Department of Linguistics, Working Papers, 35:191-202

- ↑ Chen, Zhongmin. Studies in Dialects in the Shanghai Area. Lincom Europa, 2003, p. 74.

- ↑ Introduction to Shanghainese. Pronunciation (Part 3 - Tones and Pitch Accent) Archived March 1, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Graham Thurgood, Randy J. LaPolla (2003). Graham Thurgood, Randy J. LaPolla, ed. The Sino-Tibetan languages. Volume 3 of Routledge language family series (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 86. ISBN 0-7007-1129-5. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ↑ Edkins, Joseph (1853). Grammar of the Shanghai Dialect.

- ↑ https://serica.blog/2012/12/10/new-phonetic-character/

- ↑ Wm. V. Hannas (1997). Asia's orthographic dilemma. University of Hawaii Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-8248-1892-X. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

Non-Mandarin speakers take their own shortcuts, such as 王 (Shanghai) wang "king" for 黃 wang "yellow" (pronounced Huáng in Mandarin) or 人門 (Shanghai) ningmeng (lit.) "person" and "door" for 檸檬 ningmeng "lemon," not to mention hundreds of unique forms and usages devised popularly that have no application to Mandarin at all. There is nothing new about this phenomenon. For at least two millennia, there have been two orthographies in China: the one formally sanctioned by lexicographers and the state, and a popular tradition used informally by people in their everyday lives.

() - ↑ "December - 2012 - SERICA". oldchinesebooks.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014.

- ↑ Lodwick, Kathleen L. (May 10, 1868). "The Chinese recorder". Shanghai [etc.] T. Chu [etc.] Archived from the original on May 13, 2016 – via Internet Archive.

Sources

- Lance Eccles, Shanghai dialect: an introduction to speaking the contemporary language. Dunwoody Press, 1993. ISBN 1-881265-11-0. 230 pp + cassette. (An introductory course in 29 units).

- Xiaonong Zhu, A Grammar of Shanghai Wu. LINCOM Studies in Asian Linguistics 66, LINCOM Europa, Munich, 2006. ISBN 3-89586-900-7. 201+iv pp.

Further reading

- Chen, Yiya; Gussenhoven, Carlos (2015), "Shanghai Chinese", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 45 (3): 321–327, doi:10.1017/S0025100315000043

- John A. Silsby, Darrell Haug Davis (1907). Complete Shanghai syllabary with an index to Davis and Silsby's Shanghai vernacular dictionary and with the Mandarin pronunciation of each character. American Presbyterian Mission Press. p. 150. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Joseph Edkins (1868). A grammar of colloquial Chinese: as exhibited in the Shanghai dialect (2 ed.). Presbyterian mission press. p. 225. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Shanghai Christian vernacular society (1891). Syllabary of the Shanghai vernacular: Prepared and published by the Shanghai Christian vernacular society. American Presbyterian mission press. p. 94. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Rev.John Macgowan (1868). Collection Of Phrases In The Shanghai Dialect (2 ed.). The London Missionary Society. p. 113. Archived from the original on April 15, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Gilbert McIntosh (1908). Useful phrases in the Shanghai dialect: With index-vocabulary and other helps (2 ed.). American Presbyterian mission press. p. 113. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Joseph Edkins (1869). A vocabulary of the Shanghai dialect. Presbyterian mission press. p. 151. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Charles Ho, George Foe (1940). Shanghai dialect in 4 weeks: with map of Shanghai. Chi Ming Book Co.press. p. 125. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- John Alfred Silsby (1911). Introduction to the study of the Shanghai vernacular. American Presbyterian Mission Press. p. 53. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- R. A. Parker (1923). Introduction Lessons in the Shanghai dialect: in romanized and character, with key to pronunciation. Shanghai. p. 265. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Pott, F. L. Hawks (Francis Lister Hawks), 1864-1947 | The ...

- Francis Lister Hawks Pott (1907). Lessons in the Shanghai dialect. Shanghai: Printed at the American Presbyterian mission press.

- Francis Lister Hawks Pott; Frank Joseph Rawlinson (1915). 滬語開路 = Conversational exercises in the Shanghai dialect / Hu yu kai lu = Conversational exercises in the Shanghai dialect. Shanghai: Shanghai mei hua shu guan.

- Francis Lister Hawks Pott (1924). Lessons in the Shanghai dialect (revised ed.). Printed at the Commercial Press. p. 174. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- Francis Lister Hawks Pott (1924). Lessons in the Shanghai dialect. Commercial Press.

- An English-Chinese vocabulary of the Shanghai dialect (2 ed.). Printed at the American Presbyterian Mission Press. 1913. p. 593. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- "Shanghai steps up efforts to save local language" (Archive). CNN. March 31, 2011.

External links

| Wu edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shanghai dialect. |

- Shanghainese audio lesson series: Audio lessons with accompanying dialogue and vocabulary study tools

- Shanghai Dialect: Resources on Shanghai dialect including a Web site (in Japanese) that gives common phrases with sound files

- Shanghainese-Mandarin Soundboard: A soundboard (requires Flash) of common Mandarin Chinese phrases with Shanghainese equivalents.

- Wu Association

- IAPSD | International Association for Preservation of the Shanghainese Dialect

- Recordings of Shanghainese are available through Kaipuleohone, including talking about entertainment and food, and words and sentences