Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms | |||||||||||||||

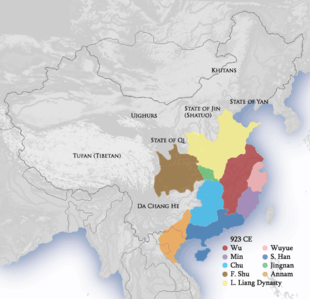

The Later Liang (yellow) and contemporary kingdoms | |||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 五代十國 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 五代十国 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | |||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BC | |||||||

| Xia dynasty c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC | |||||||

| Shang dynasty c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC | |||||||

| Zhou dynasty c. 1046 – 256 BC | |||||||

| Western Zhou | |||||||

| Eastern Zhou | |||||||

| Spring and Autumn | |||||||

| Warring States | |||||||

| IMPERIAL | |||||||

| Qin dynasty 221–206 BC | |||||||

| Han dynasty 206 BC – 220 AD | |||||||

| Western Han | |||||||

| Xin dynasty | |||||||

| Eastern Han | |||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | |||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | |||||||

| Jin dynasty 265–420 | |||||||

| Western Jin | |||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | ||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | |||||||

| Sui dynasty 581–618 | |||||||

| Tang dynasty 618–907 | |||||||

| (Second Zhou dynasty 690–705) | |||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–960 |

Liao dynasty 907–1125 | ||||||

| Song dynasty 960–1279 |

|||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | ||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | ||||||

| Yuan dynasty 1271–1368 | |||||||

| Ming dynasty 1368–1644 | |||||||

| Qing dynasty 1644–1912 | |||||||

| MODERN | |||||||

| Republic of China 1912–1949 | |||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | |||||||

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period was an era of political upheaval in 10th-century Imperial China. Five states quickly succeeded one another in the Central Plain, and more than a dozen concurrent states were established elsewhere, mainly in South China. It was the last prolonged period of multiple political division in Chinese imperial history.[1]

Traditionally, the era started with the fall of the Tang dynasty in 907 AD and ended with the founding of the Song dynasty in 960. Many states had been de facto independent kingdoms long before 907. After the Tang had collapsed, the kings who controlled the Central plain crowned themselves as emperors. War between kingdoms occurred frequently to gain control of the central plain for legitimacy and then over the rest of China. The last of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms states, the Northern Han, was not vanquished until 979.

States

Background

Towards the end of the Tang, the imperial government granted increased powers to the jiedushi, the regional military governors. The Huang Chao Rebellion weakened the imperial government, and by the early 10th century the jiedushi commanded de facto independence from its authority. In the last decades of the dynasty, they were not even appointed by the court any more, but developed hereditary systems, from father to son or from patron to protégé. They had their own armies rivalling the "palace armies" and amassed huge wealth, as testified by their sumptuous tombs.[2] Thus ensued the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Important Jiedushi

- Zhu Wen at Bianzhou (modern Kaifeng, Henan), precursor to Later Liang

- Li Keyong and Li Cunxu at Taiyuan (modern Taiyuan, Shanxi), precursor to Later Tang

- Liu Rengong and Liu Shouguang at Youzhou (modern Beijing), precursor to Yan

- Li Maozhen at Fengxiang (modern Fengxiang County, Shaanxi province), precursor to Qi

- Luo Shaowei at Weibo (modern Daming County, Hebei province)

- Wang Rong at Zhenzhou (modern Zhengding County, Hebei province)

- Wang Chuzhi at Dingzhou (modern Dingzhou, Hebei)

- Yang Xingmi at Yangzhou (modern Yangzhou, Jiangsu), precursor to Wu

- Qian Liu at Hangzhou (modern Hangzhou, Zhejiang), precursor to Wuyue

- Ma Yin at Tanzhou (modern Changsha, Hunan), precursor to Chu

- Wang Shenzhi at Fuzhou (modern Fuzhou, Fujian), precursor to Min

- Liu Yin at Guangzhou (modern Guangzhou, Guangdong), precursor to Southern Han

- Wang Jian at Chengdu (modern Chengdu, Sichuan), precursor to Former Shu

Five Dynasties

Later Liang

During the Tang Dynasty, the warlord Zhu Wen held the most power in southern China. Although he was originally a member of Huang Chao's rebel army, he took on a crucial role in suppressing the Huang Chao Rebellion. For this function, he was awarded the Xuanwu Jiedushi title. Within a few years, he had consolidated his power by destroying neighbours and forcing the move of the imperial capital to Luoyang, which was within his region of influence. In 904, he executed Emperor Zhaozong of Tang and made his 13-year-old son a subordinate ruler. Three years later, he induced the boy emperor to abdicate in his favour. He then proclaimed himself emperor, thus beginning the Later Liang.

Later Tang

During the final years of the Tang Dynasty, rival warlords declared independence in the provinces they governed—not all of which recognized the emperor's authority. Li Cunxu and Liu Shouguang (劉守光) fiercely fought the regime forces to conquer northern China; Li Cunxu succeeded. He defeated Liu Shouguang (who had proclaimed a Yan Empire in 911) in 915, and declared himself emperor in 923; within a few months, he brought down the Later Liang regime. Thus began the Shatuo Later Tang — the first in a long line of conquest dynasties. After reuniting much of northern China, in 925 Cunxu conquered the Former Shu, a regime that had been set up in Sichuan.

Later Jin

The Later Tang had a few years of relative calm, followed by unrest. In 934, Sichuan again asserted independence. In 936, Shi Jingtang, a Shatuo jiedushi from Taiyuan, was aided by the ethnic-Khitan Liao dynasty in a rebellion against the Later Tang. In return for their aid, Shi Jingtang promised annual tribute and the Sixteen Prefectures (modern northern Hebei and Beijing) to the Khitans. The rebellion succeeded; Shi Jingtang became emperor in this same year.

Not long after the founding of the Later Jin, the Khitans came to regard the emperor as a proxy ruler for China proper. In 943, the Khitans declared war and within three years seized the capital, Kaifeng, marking the end of Later Jin. But while they had conquered vast regions of China, the Khitans were unable or unwilling to control those regions and retreated from them early in the next year.

Later Han

To fill the power vacuum, the jiedushi Liu Zhiyuan entered the imperial capital in 947 and proclaimed the advent of the Later Han, establishing a third successive Shatuo reign. This was the shortest of the five dynasties. Following a coup in 951, General Guo Wei, a Han Chinese, was enthroned, thus beginning the Later Zhou. However, Liu Chong, a member of the Later Han imperial family, established a rival Northern Han regime in Taiyuan and requested Khitan aid to defeat the Later Zhou.

Later Zhou

After the death of Guo Wei in 951, his adopted son Chai Rong succeeded the throne and began a policy of expansion and reunification. In 954, his army defeated combined Khitan and Northern Han forces, ending their ambition of toppling the Later Zhou. Between 956 and 958, forces of Later Zhou conquered much of Southern Tang, the most powerful regime in southern China, which ceded all the territory north of the Yangtze in defeat. In 959, Chai Rong attacked the Liao in an attempt to recover territories ceded during the Later Jin. After many victories, he succumbed to illness.

In 960, the general Zhao Kuangyin staged a coup and took the throne for himself, founding the Northern Song Dynasty. This is the official end of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. During the next two decades, Zhao Kuangyin and his successor Zhao Kuangyi defeated the other remaining regimes in China proper, conquering Northern Han in 979, and reunifying China completely in 982.

Northern Han

Though considered one of the ten kingdoms, the Northern Han was based in the traditional Shatuo stronghold of Shanxi. It was created after the last of three dynasties created by Shatuo Turks fell to the Han-governed Later Zhou in 951. With the protection of the powerful Liao, the Northern Han maintained nominal independence until the Song Dynasty wrested it from the Khitan in 979.

Ten Kingdoms

Unlike the dynasties of northern China, which succeeded one another in rapid succession, the regimes of South China were generally concurrent, each controlling a specific geographical area. These were known as "The Ten Kingdoms".

Wu

The Kingdom of Wu (902–937) was established in modern-day Jiangsu, Anhui, and Jiangxi. It was founded by Yang Xingmi, who became a Tang Dynasty military governor in 892. The capital was initially at Guangling (present-day Yangzhou) and later moved to Jinling (present-day Nanjing). The kingdom fell in 937 when it was taken from within by the founder of the Southern Tang.

Wuyue

The Kingdom of Wuyue was the longest-lived (907–978) and among the most powerful of the southern states. Wuyue was known for its learning and culture. It was founded by Qian Liu, who set up his capital at Xifu (modern-day Hangzhou). It was based mostly in modern Zhejiang province but also held parts of southern Jiangsu. Qian Liu was named the Prince of Yue by the Tang emperor in 902; the Prince of Wu was added in 904. After the fall of the Tang Dynasty in 907, he declared himself king of Wuyue. Wuyue survived until the eighteenth year of the Song dynasty, when Qian Shu surrendered to the expanding dynasty.

Min

The Kingdom of Min (909–945) was founded by Wang Shenzhi, who named himself the Prince of Min with its capital at Changle (present-day Fuzhou). One of Shenzhi’s sons proclaimed the independent state of Yin in the northeast of Min territory. The Southern Tang took that territory after the Min asked for help. Despite declaring loyalty to the neighboring Wuyue, the Southern Tang finished its conquest of Min in 945.

Southern Han

The Southern Han (917–971) was founded in Guangzhou (also known as Canton) by Liu Yan. His brother, Liu Yin, was named regional governor by the Tang court. The kingdom included Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan.

Chu

The Chu (927–951) was founded by Ma Yin with the capital at Changsha. The kingdom held Hunan and northeastern Guangxi. Ma was named regional military governor by the Tang court in 896, and named himself the Prince of Chu with the fall of the Tang in 907. This status as the Prince of Chu was confirmed by the Later Tang in 927. The Southern Tang absorbed the state in 951 and moved the royal family to its capital in Nanjing, although Southern Tang rule of the region was temporary, as the next year former Chu military officers under the leadership of Liu Yan seized the territory. In the waning years of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, the region was ruled by Zhou Xingfeng.

Northern Han

The Northern Han was founded by Liu Min (劉旻), formerly known as Liu Chong (劉崇), and lasted from 951 to 979. It has the capital at Taiyuan.

Jingnan (also known as Nanping)

The smallest of the southern states, Jingnan (924–963), was founded by Gao Jichang. It was based in Jiangling and held two other districts southwest of present-day Wuhan in Hubei. Gao was in the service of the Later Liang (the successor of the Tang in North China). Gao’s successors claimed the title of King of Nanping after the fall of the Later Liang in 924. It was a small and weak kingdom, and thus tried to maintain good relations with each of the Five Dynasties. The kingdom fell to advancing armies of the Song in 963.

Former Shu

Former Shu (907–25) was founded after the fall of the Tang Dynasty by Wang Jian, who held his court in Chengdu. The kingdom held most of present-day Sichuan, western Hubei, and parts of southern Gansu and Shaanxi. Wang was named military governor of western Sichuan by the Tang court in 891. The kingdom fell when his son surrendered in the face of an advance by the Later Tang in 925.

Later Shu

The Later Shu (935–965) is essentially a resurrection of the previous Shu state that had fallen a decade earlier to the Later Tang. Because the Later Tang was in decline, Meng Zhixiang found the opportunity to reassert Shu’s independence. Like the Former Shu, the capital was at Chengdu and it basically controlled the same territory as its predecessor. The kingdom was ruled well until forced to succumb to Song armies in 965.

Southern Tang

The Southern Tang (937–975) was the successor state of Wu as Li Bian (Emperor Liezu) took the state over from within in 937. Expanding from the original domains of Wu, it eventually took over Yin, Min, and Chu, holding present-day southern Anhui, southern Jiangsu, much of Jiangxi, Hunan, and eastern Hubei at its height. The kingdom became nominally subordinate to the expanding Song in 961 and was invaded outright in 975, when it was formally absorbed into Song China.

Transitions between kingdoms

Although more stable than northern China as a whole, southern China was also torn apart by warfare. Wu quarrelled with its neighbours, a trend that continued as Wu was replaced with Southern Tang. In the 940s Min and Chu underwent internal crises which Southern Tang handily took advantage of, destroying Min in 945 and Chu in 951. Remnants of Min and Chu, however, survived in the form of Qingyuan Jiedushi and Wuping Jiedushi for many years after. With this, Southern Tang became the undisputedly most powerful regime in southern China. However, it was unable to defeat incursions by the Later Zhou between 956 and 958, and ceded all of its land north of the Yangtze River.

The Song dynasty, established in 960, was determined to reunify China. Jingnan and Wuping Jiedushi were swept away in 963, Later Shu in 965, Southern Han in 971, and Southern Tang in 975. Finally, Wuyue and Qingyuan Jiedushi gave up their land to Northern Song in 978, bringing all of southern China under the control of the central government.

In common with other periods of fragmentation, the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period resulted in a division between northern and southern China. The greater stability of the Ten Kingdoms, especially the longevity of Wu Yue and Southern Han, would contribute to the development of distinct regional identities within China. The distinction was reinforced by the Old History and the New History. Written from the northern viewpoint, these chronicles organized the history around the Five Dynasties (the north), presenting the Ten Kingdoms (the south) as illegitimate, self-absorbed and indulgent.[2]

Culture

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period turned away from the international cultural mood of the Tang dynasty and appears as a transition towards the solidified national culture of the Song dynasty.[3] Throughout the period, there was marked cultural and economic growth, rather than decline.[1]

Although short, the period saw cultural innovations in different areas. Pottery saw the appearance of "white ceramics." In painting, the "varied landscape" of China was inspired by Taoism. It emphasized the sacredness of mountains as places between heaven and earth and depicted the natural world as a source of harmony.[4]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. |

- Old History of the Five Dynasties

- Annam (Chinese province)

- Family trees of the emperors of the Five Dynasties

- Chinese sovereign

- Liao dynasty

- Conquest of Southern Tang by Song

- Zizhi Tongjian

- Islam during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period

References

- 1 2 Glen Dudbridge (2013). A Portrait of Five Dynasties China: From the Memoirs of Wang Renyu (880-956). Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780191749537. Dudbridge actually quotes Reischauer's Ennin's Travels.

- 1 2 Xiu Ouyang (2004). Historical Records of the Five Dynasties. Translated by Richard L. Davis. Columbia University Press. pp. LV–LXV. ISBN 9780231128278. The information was taken from Richard L. Davis's introduction.

- ↑ The Culture of China. Britannica Educational Publishing. 2011. p. 245. ISBN 9781615301836.

- ↑ "Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms". Museum of Chinese Art and Ethnography, Parma.

Further reading

- Davis, Richard L. (2015). From Warhorses to Ploughshares: The Later Tang Reign of Emperor Mingzong. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789888208104.

- Dudbridge, Glen (2013). A Portrait of Five Dynasties China: From the Memoirs of Wang Renyu (880-956). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199670680.

- Hung, Hing Ming (2014). Ten States, Five Dynasties, One Great Emperor: How Emperor Taizu Unified China in the Song Dynasty. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62894-072-5.

- Kurz, Johannes L. (2011). China's Southern Tang Dynasty (937-976). Routledge. ISBN -9780415454964.

- Lorge, Peter, ed. (2011). Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. The Chinese University Press. ISBN 962996418X.

- Ouyang Xiu (2004) [1077]. Historical Records of the Five Dynasties. (transl. Richard L. Davis). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12826-6.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1954). Empire of Min: A South China Kingdom of the Tenth Century. Tuttle Publishing.

- Wang Gungwu (1963). The Structure of Power in North China During the Five Dynasties. Stanford University Press.

- Wang Hongjie (2011). Power and Politics in Tenth-Century China: The Former Shu Regime. Cambria Press. ISBN 1604977647.

| Preceded by Tang dynasty |

Dynasties in Chinese history 907–960 |

Succeeded by Song dynasty Liao dynasty |