Malayo-Polynesian languages

| Malayo-Polynesian | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Southeast Asia, the Pacific, Madagascar |

| Linguistic classification |

Austronesian

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Malayo-Polynesian |

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-5 | poz |

| Glottolog | mala1545[1] |

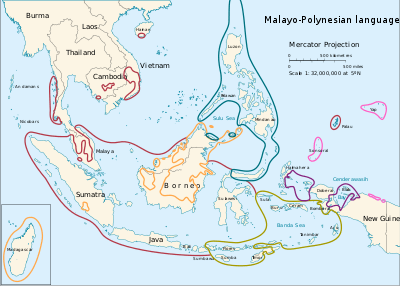

The western sphere of Malayo-Polynesian languages. (The bottom three are Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian)

| |

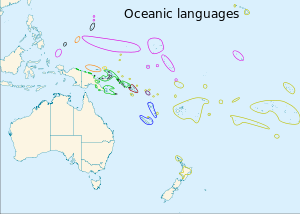

The branches of the Oceanic languages:

The black ovals at the northwestern limit of Micronesia are the Sunda–Sulawesi languages called Palauan and Chamorro. The black circles in with the green are offshore Papuan languages. | |

The Malayo-Polynesian languages are a subgroup of the Austronesian languages, with approximately 385.5 million speakers. The Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken by the Austronesian people of the island nations of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Ocean, with a smaller number in continental Asia, going well into the Malay peninsula. Cambodia and Vietnam serve as the northwest geographic outlier. On the northernmost geographical outlier does not pass beyond the north of Pattani, which is located in southern Thailand. Malagasy is spoken in the island of Madagascar located off the eastern coast of Africa in the Indian Ocean. Part of the language family shows a strong influence of Sanskrit and particularly Arabic as the Western part of the region has been a stronghold of Hinduism, Buddhism, and, since the 10th century, Islam.

Two morphological characteristics of the Malayo-Polynesian languages are a system of affixation and the reduplication (repetition of all or part of a word, such as wiki-wiki) to form new words. Like other Austronesian languages they have small phonemic inventories; thus a text has few but frequent sounds. The majority also lack consonant clusters (e.g., [str] in English). Most also have only a small set of vowels, five being a common number.

Languages

The Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian languages are spoken by about 230 million people and include Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Sundanese, Javanese, Buginese, Balinese, Acehnese; and also the Oceanic languages, including Tolai, Gilbertese, Fijian, and Polynesian languages such as Hawaiian, Māori, Samoan, Tahitian, and Tongan. Malay is also the native language in Singapore and Brunei.

The Philippine languages are the most linguistically archaic branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language family, and are spoken by around 100 million people between Orchid Island Taiwan, the entire Philippine archipelago, and Sulawesi Indonesia. Philippine languages include Tagalog (Filipino), Cebuano, Ilokano, Hiligaynon, Central Bikol, Waray, and Kapampangan, each with at least three million speakers.

In Northern Borneo, the most widely spoken language is Kadazan-Dusun, with over 200,000+ speakers and Lundayeh Language is the one of the minority language in the southerwest of Sabah and in the northern of Sarawak.

Classification

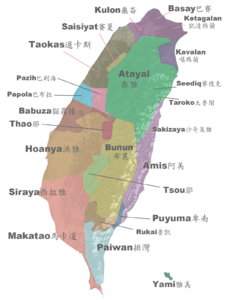

Relation to Austronesian languages on Taiwan

The Malayo-Polynesian languages share several phonological and lexical innovations with the eastern Formosan languages, including the leveling of proto-Austronesian *t, *C to /t/ and *n, *N to /n/, a shift of *S to /h/, and vocabulary such as *lima "five" which are not attested in other Formosan languages. However, it does not align with any one branch.

Internal classification

Malayo-Polynesian consists of a large number of small local language clusters, with the one exception being Oceanic, the only large group which is universally accepted; its parent language Proto-Oceanic has been reconstructed in all aspects of its structure (phonology, lexicon, morphology and syntax). All other large groups within Malayo-Polynesian are controversial.

Blust (1993)

The most influential proposal for the internal subgrouping of the Malayo-Polynesian languages was made Robert Blust who presented several papers advocating a division into two major branches, viz. Western Malayo-Polynesian and Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian.[2]

Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian is widely accepted as a subgroup, although some objections have been raised against its validity as a genetic subgroup.[3][4] On the other hand, Western Malayo-Polynesian is now generally held (including by Blust himself) to be an umbrella term without genetic relevance. Taking into account the Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian hypothesis, the Malayo-Polynesian languages can be divided into the following subgroups (proposals for larger subgroups are given below):[5]

- Philippine languages

- Sama–Bajaw languages

- North Bornean languages

- Kayan–Murik languages

- Land Dayak languages

- Barito languages (including Malagasy)

- Moken language

- Malayo-Chamic languages

- Northwest Sumatran languages (probably including the aberrant Enggano language)

- Rejang language

- Lampung language

- Sundanese language

- Javanese language

- Madurese language

- Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages

- Celebic languages

- South Sulawesi languages

- Palauan language

- Chamorro language

- Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages

- Central Malayo-Polynesian languages

- Sumba–Flores languages

- Flores–Lembata languages

- Selaru languages

- Kei–Tanimbar languages

- Aru languages

- Central Maluku languages

- Timoric languages (also called Timor–Babar languages)

- Kowiai language

- Teor-Kur language

- Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages

- South Halmahera–West New Guinea languages

- Oceanic languages (approximately 450 languages)

- Central Malayo-Polynesian languages

The position of the recently "rediscovered" Nasal language (spoken on Sumatra) is still unclear, but it shares most features of its lexicon and phonological history with either Lampung or Rejang.[6]

Malayo-Sumbawan

The Malayo-Sumbawan languages are a proposal by Adelaar (2005) which unites the Malayo-Chamic languages, the Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa languages, Madurese and Sundanese into a single subgroup based on phonological and lexical evidence.[7]

Greater North Borneo

The Greater North Borneo hypothesis, which unites all languages spoken on Borneo except for the Barito languages together with the Malayo-Chamic languages, Rejang and Sundanese into a single subgroup, was first proposed by Blust (2010) and further elaborated by Smith (2017).[8][9]

- Greater North Borneo

Because of the inclusion of Malayo-Chamic and Sundanese, Greater North Borneo is incompatible with the Malayo-Sumbawan proposal, which latter is explicitly rejected by Blust. The Greater North Borneo subgroup is based solely on lexical evidence.

Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian

Zobel (2002) proposes a Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian subgroup, based on putative shared innovations in the Austronesian alignment and syntax found throughout Indonesia apart from much of Borneo and the north of Sulawesi. This subgroup comprises the languages of the Greater Sunda Islands (Malayo-Chamic, Northwest Sumatran, Lampung, Sundanese, Javanese, Madurese, Bali-Sasak-Sumbawa) and most of Sulawesi (Celebic, South Sulawesi), Palauan, Chamorro and the Central–Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages.[10] This hypothesis is one of the few attempts to link certain Western Malayo-Polynesian languages with the Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian languages in a higher intermediate node, but has received little further scholarly attention.

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Malayo-Polynesian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Blust, R. (1993). Central and Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian. Oceanic Linguistics, 32(2), 241-293.

- ↑ Ross, Malcolm (2005), "Some current issues in Austronesian linguistics", in D.T. Tryon, ed., Comparative Austronesian Dictionary, 1, 45-120. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- ↑ Donohue, M., & Grimes, C. (2008). Yet More on the Position of the Languages of Eastern Indonesia and East Timor. Oceanic Linguistics, 47(1), 114-158.

- ↑ Adelaar, K. Alexander, and Himmelmann, Nikolaus. 2005. The Austronesian languages of Asia and Madagascar. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Anderbeck, Karl; Aprilani, Herdian (2013). The Improbable Language: Survey Report on the Nasal Language of Bengkulu, Sumatra. SIL Electronic Survey Report. SIL International.

- ↑ Adelaar, A. (2005). Malayo-Sumbawan. Oceanic Linguistics, 44(2), 357-388.

- ↑ Blust, R. (2010). The Greater North Borneo Hypothesis. Oceanic Linguistics, 49(1), 44-118.

- ↑ Smith, Alexander. 2017. The Languages of Borneo: A Comprehensive Classification. PhD Dissertation: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

- ↑ Fay Wouk and Malcolm Ross (ed.), 2002. The history and typology of western Austronesian voice systems. Australian National University.