Malay language

| Malay | |

|---|---|

| Bahasa Melayu / بهاس ملايو | |

| Native to | Indonesia, Malaysia, East Timor, Brunei, Singapore, Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands |

| Ethnicity | Malays |

Native speakers |

77 million (2007)[1] Total: 250–300 million (2009)[2] |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | |

|

Latin (Malay alphabet) | |

|

Manually Coded Malay Sistem Isyarat Bahasa Indonesia | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in |

(Local Malay enjoys the status of a regional language in Sumatra and Kalimantan (Borneo) apart from the national normative standard of Indonesian) |

| Regulated by |

Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa; Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (Institute of Language and Literature); Majlis Bahasa Brunei-Indonesia-Malaysia (Brunei–Indonesia–Malaysia Language Council – MABBIM) (a trilateral joint-venture) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

ms |

| ISO 639-2 |

may (B) msa (T) |

| ISO 639-3 |

msa – inclusive codeIndividual codes: kxd – Brunei Malayind – Indonesianzsm – Malaysianjax – Jambi Malaymeo – Kedah Malaykvr – Kerincixmm – Manado Malaymin – Minangkabaumui – Musizmi – Negeri Sembilanmax – North Moluccanmfa – Pattani Malay |

| Glottolog |

indo1326 partial match[4] |

| Linguasphere |

31-MFA-a |

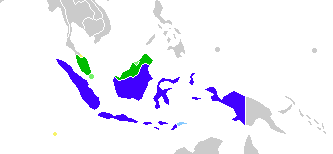

Indonesia

Malaysia

Singapore and Brunei, where Malay is an official language

East Timor, where Indonesian is a working language

Southern Thailand and the Cocos Isl., where other varieties of Malay are spoken | |

Malay (/məˈleɪ/;[5] Malay: Bahasa Melayu بهاس ملايو) is a major language of the Austronesian family spoken in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. A language of the Malays, it is spoken by 290 million people[6] across the Strait of Malacca, including the coasts of the Malay Peninsula of Malaysia and the eastern coast of Sumatra in Indonesia, and has been established as a native language of part of western coastal Sarawak and West Kalimantan in Borneo. It is also used as a trading language in the southern Philippines, including the southern parts of the Zamboanga Peninsula, the Sulu Archipelago and the southern predominantly Muslim-inhabited municipalities of Bataraza and Balabac in Palawan.

As the Bahasa Kebangsaan, or Bahasa Nasional ("national language") of several states, Standard Malay has various official names. In Malaysia, it is designated as either Bahasa Malaysia ("Malaysian language") or Bahasa Melayu ("Malay language"). In Singapore and Brunei, it is called Bahasa Melayu ("Malay language"); and in Indonesia, an autonomous normative variety called Bahasa Indonesia ("Indonesian language") is designated the Bahasa Persatuan/Pemersatu ("unifying language"/lingua franca). However, in areas of central to southern Sumatra where vernacular varieties of Malay are indigenous, Indonesians refer to it as Bahasa Melayu and consider it one of their regional languages.

Standard Malay, also called Court Malay, was the literary standard of the pre-colonial Malacca and Johor Sultanates, and so the language is sometimes called Malacca, Johor or Riau Malay (or various combinations of those names) to distinguish it from the various other Malayan languages. According to Ethnologue 16, several of the Malayan varieties they currently list as separate languages, including the Orang Asli varieties of Peninsular Malay, are so closely related to standard Malay that they may prove to be dialects. There are also several Malay trade and creole languages which are based on a lingua franca derived from Classical Malay as well as Macassar Malay, which appears to be a mixed language.

Origin

Malay historical linguists agree on the likelihood of the Malay homeland being in western Borneo stretching to the Bruneian coast.[7] A form known as Proto-Malay was spoken in Borneo at least by 1000 BCE and was, it has been argued, the ancestral language of all subsequent Malayan languages. Its ancestor, Proto-Malayo-Polynesian, a descendant of the Proto-Austronesian language, began to break up by at least 2000 BCE, possibly as a result of the southward expansion of Austronesian peoples into Maritime Southeast Asia from the island of Taiwan.[8]

History

.pdf.jpg)

The history of the Malay language can be divided into five periods: Old Malay, the Transitional Period, the Malacca Period (Classical Malay), Late Modern Malay and modern Malay. It is not clear that Old Malay was actually the ancestor of Classical Malay, but this is thought to be quite possible.[9]

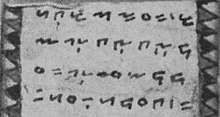

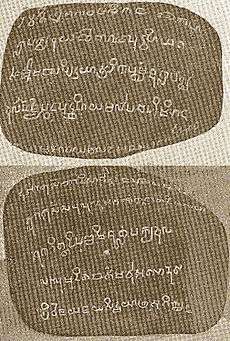

Old Malay was influenced by the Sanskrit literary language of Classical India and a scriptural language of Hinduism and Buddhism. Sanskrit loanwords can be found in Old Malay vocabulary. The earliest known stone inscription in the Old Malay language was found in Sumatra, written in the Pallava variety of the Grantha alphabet[10] and dates back to 7th century – known as the Kedukan Bukit inscription, it was discovered by the Dutchman M. Batenburg on November 29, 1920 at Kedukan Bukit, South Sumatra, on the banks of the Tatang, a tributary of the Musi River. It is a small stone of 45 by 80 centimetres (18 by 31 in).

The earliest surviving manuscript in Malay is the Tanjong Tanah Law in post-Pallava letters. This 14th-century pre-Islamic legal text produced in the Adityawarman era (1345–1377) of Dharmasraya, a Hindu-Buddhist kingdom that arose after the end of Srivijayan rule in Sumatra. The laws were for the Minangkabau people, who today still live in the highlands of Sumatra.

The Malay language came into widespread use as the lingua franca of the Malacca Sultanate (1402–1511). During this period, the Malay language developed rapidly under the influence of Islamic literature. The development changed the nature of the language with massive infusion of Arabic, Tamil and Sanskrit vocabularies, called Classical Malay. Under the Sultanate of Malacca the language evolved into a form recognisable to speakers of modern Malay. When the court moved to establish the Johor Sultanate, it continued using the classical language; it has become so associated with Dutch Riau and British Johor that it is often assumed that the Malay of Riau is close to the classical language. However, there is no closer connection between Malaccan Malay as used on Riau and the Riau vernacular.[11]

One of the oldest surviving letters written in Malay is a letter from Sultan Abu Hayat of Ternate, Maluku Islands in present-day Indonesia, dated around 1521–1522. The letter is addressed to the king of Portugal, following contact with Portuguese explorer Francisco Serrão.[12] The letters show sign of non-native usage; the Ternateans used (and still use) the unrelated Ternate language, a West Papuan language, as their first language. Malay was used solely as a lingua franca for inter-ethnic communications.[12]

Classification and related languages

Malay is a member of the Austronesian family of languages, which includes languages from Southeast Asia and the Pacific Ocean, with a smaller number in continental Asia. Malagasy, a geographic outlier spoken in Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, is also a member of this language family. Although each language of the family is mutually unintelligible, their similarities are rather striking. Many roots have come virtually unchanged from their common ancestor, Proto-Austronesian language. There are many cognates found in the languages' words for kinship, health, body parts and common animals. Numbers, especially, show remarkable similarities.

Within Austronesian, Malay is part of a cluster of numerous closely related forms of speech known as the Malayan languages, which were spread across Malaya and the Indonesian archipelago by Malay traders from Sumatra. There is disagreement as to which varieties of speech popularly called "Malay" should be considered dialects of this language, and which should be classified as distinct Malay languages. The vernacular of Brunei—Brunei Malay—for example, is not readily intelligible with the standard language, and the same is true with some varieties on the Malay Peninsula such as Kedah Malay. However, both Brunei and Kedah are quite close.[13]

The closest relatives of the Malay languages are those left behind on Sumatra, such as the Minangkabau language, with 5.5 million speakers on the west coast.

Writing system

Malay is now written using the Latin script (Rumi), although an Arabic script called Arab Melayu or Jawi also exists. Rumi is official in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Malay uses Hindu-Arabic numerals.

Rumi and Jawi are co-official in Brunei only. Names of institutions and organisations have to use Jawi and Rumi (Latin) scripts. Jawi is used fully in schools, especially the Religious School, Sekolah Agama, which is compulsory during the afternoon for Muslim students aged from around 6–7 up to 12–14.

Efforts are currently being undertaken to preserve Jawi in rural areas of Malaysia, and students taking Malay language examinations in Malaysia have the option of answering questions using Jawi.

The Latin script, however, is the most commonly used in Brunei and Malaysia, both for official and informal purposes.

Historically, Malay has been written using various scripts. Before the introduction of Arabic script in the Malay region, Malay was written using the Pallava, Kawi and Rencong scripts; these are still in use today, such as the Cham alphabet used by the Chams of Vietnam and Cambodia. Old Malay was written using Pallava and Kawi script, as evident from several inscription stones in the Malay region. Starting from the era of kingdom of Pasai and throughout the golden age of the Malacca Sultanate, Jawi gradually replaced these scripts as the most commonly used script in the Malay region. Starting from the 17th century, under Dutch and British influence, Jawi was gradually replaced by the Rumi script.[14]

Extent of use

Malay is spoken in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, East Timor, Singapore, parts of Thailand[15] and southern Philippines. Indonesia regulates its own normative variety of Malay, while Malaysia and Singapore use the same standard.[16] Brunei, in addition to Standard Malay, uses a distinct vernacular dialect called Brunei Malay. In East Timor, Indonesian is recognised by the constitution as one of the two working languages (the other being English), alongside the official languages of Tetum and Portuguese.[17] The extent to which Malay is used in these countries varies depending on historical and cultural circumstances. Malay is the national language in Malaysia by Article 152 of the Constitution of Malaysia, and became the sole official language in Peninsular Malaysia in 1968 and in East Malaysia gradually from 1974. English continues, however, to be widely used in professional and commercial fields and in the superior courts. Other minority languages are also commonly used by the country's large ethnic minorities. The situation in Brunei is similar to that of Malaysia. In the Philippines, Malay is spoken by a minority of the Muslim population residing in Mindanao (specifically the Zamboanga Peninsula) and the Sulu Archipelago. However, they mostly speak it in a form of creole resembling Sabah Malay. Historically, it was the primary trading language of the archipelago prior to Spanish occupation. Indonesian is spoken by the overseas Indonesian community in Davao City, and functional phrases are taught to members of the Philippine Armed Forces and to students.

Phonology

Malay, like most Austronesian languages, is not a tonal language.

Consonants

The consonants of Malaysian[18] and also Indonesian[19] are shown below. Non-native consonants that only occur in borrowed words, principally from Arabic and English, are shown in brackets.

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |||

| Plosive/Affricate | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | (ʔ) | |

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | ɡ | |||

| Fricative | voiceless | (f) | (θ) | s | (ʃ) | (x) | h |

| voiced | (v) | (ð) | (z) | (ɣ) | |||

| Approximant | central | j | w | ||||

| lateral | l | ||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

Orthographic note: The sounds are represented orthographically by their symbols as above, except:

- /ð/ is 'z', the same as the /z/ sound (only occurs in Arabic loanwords originally containing the /ð/ sound, but the writing is not distinguished from Arabic loanwords with /z/ sound, and this sound must be learned separately by the speakers).

- /ɲ/ is 'ny'

- /ŋ/ is 'ng'

- /θ/ is represented as 's', the same as the /s/ sound (only occurs in Arabic loanwords originally containing the /θ/ sound, but the writing is not distinguished from Arabic loanwords with /s/ sound, and this sound must be learned separately by the speakers). Previously (before 1972), this sound was written 'th' in Standard Malay (not Indonesian)

- the glottal stop /ʔ/ is final 'k' or an apostrophe ' (although some words have this glottal stop in the middle, such as rakyat)

- /tʃ/ is 'c'

- /dʒ/ is 'j'

- /ʃ/ is 'sy'

- /x/ is 'kh'

- /j/ is 'y'

Loans from Arabic:

- Phonemes which occur only in Arabic loans may be pronounced distinctly by speakers who know Arabic. Otherwise they tend to be replaced with native sounds.

| Distinct | Assimilated | Example |

|---|---|---|

| /x/ | /k/, /h/ | khabar, kabar "news" |

| /ð/ | /d/, /l/ | redha, rela "good will" |

| /zˁ/ | /l/, /z/ | lohor, zuhur "noon (prayer)" |

| /ɣ/ | /ɡ/, /r/ | ghaib, raib "hidden" |

| /ʕ/ | /ʔ/ | saat, sa'at "second (time)" |

Vowels

Malay originally had four vowels, but in many dialects today, including Standard Malay, it has six.[18] The vowels /e, o/ are much less common than the other four.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open | a |

Orthographic note: both /e/ and /ə/ are written as 'e'. This means that there are some homographs, so perang can be either /pəraŋ/ ("war") or /peraŋ/ ("blond") (but in Indonesia perang with /e/ sound is also written as pirang).

Some analyses regard /ai, au, oi/ as diphthongs.[20][21] However, [ai] and [au] can only occur in open syllables, such as cukai ("tax") and pulau ("island"). Words with a phonetic diphthong in a closed syllable, such as baik ("good") and laut ("sea"), are actually two syllables. An alternative analysis therefore treats the phonetic diphthongs [ai], [au] and [oi] as a sequence of a monophthong plus an approximant: /aj/, /aw/ and /oj/ respectively.[22]

There is a rule of vowel harmony: the non-open vowels /i, e, u, o/ in bisyllabic words must agree in height, so hidung ("nose") is allowed but *hedung is not.[23]

Grammar

Malay is an agglutinative language, and new words are formed by three methods: attaching affixes onto a root word (affixation), formation of a compound word (composition), or repetition of words or portions of words (reduplication). Nouns and verbs may be basic roots, but frequently they are derived from other words by means of prefixes, suffixes and circumfixes.

Malay does not make use of grammatical gender, and there are only a few words that use natural gender; the same word is used for he and she or for his and her. There is no grammatical plural in Malay either; thus orang may mean either "person" or "people". Verbs are not inflected for person or number, and they are not marked for tense; tense is instead denoted by time adverbs (such as "yesterday") or by other tense indicators, such as sudah "already" and belum "not yet". On the other hand, there is a complex system of verb affixes to render nuances of meaning and to denote voice or intentional and accidental moods.

Malay does not have a grammatical subject in the sense that English does. In intransitive clauses, the noun comes before the verb. When there is both an agent and an object, these are separated by the verb (OVA or AVO), with the difference encoded in the voice of the verb. OVA, commonly but inaccurately called "passive", is the basic and most common word order.

Borrowed words

The Malay language has many words borrowed from Arabic (in particular religious terms), Sanskrit, Tamil, Persian, Portuguese, Dutch, Sinitic languages and more recently, English (in particular many scientific and technological terms).

Examples

Despite the different vocabulary used by the two standard versions of the language, Malay speakers should be able to understand the translated passages below.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

| English | Indonesian language | Malaysian language |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Declaration of Human Rights | Pernyataan Umum tentang Hak Asasi Manusia | Perisytiharan Hak Asasi Manusia sejagat |

| Article 1 | Pasal 1 | Perkara 1 |

| All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. | Semua orang dilahirkan merdeka dan mempunyai martabat dan hak-hak yang sama. Mereka dikaruniai akal dan hati nurani dan hendaknya bergaul satu sama lain dalam semangat persaudaraan. | Semua manusia dilahirkan bebas dan sama rata dari segi maruah dan hak-hak. Mereka mempunyai pemikiran dan perasaan hati dan hendaklah bergaul dengan semangat persaudaraan. |

Basic phrases in Malay

In Malaysia and Indonesia, to greet somebody with "Selamat pagi" or "Selamat sejahtera" would be considered very formal, and the borrowed word "Hi" would be more usual among friends; similarly "Bye-bye" is often used when taking one's leave. However, if you're a Muslim and the Malay person you're talking to is also a Muslim, it would be more appropriate to use the Islamic greeting of 'Assalamualaikum'. Muslim Malays, especially in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, rarely use 'Selamat pagi' (Good morning), 'Selamat tengah hari (Good "early" afternoon), 'Selamat petang' (Good "late" afternoon/evening),'Selamat malam' (Good night) or 'Selamat tinggal / Selamat jalan' (Good bye) when talking to one another.

| Malay Phrase | IPA | English Translation |

| Selamat datang | /səlamat dataŋ/ | Welcome (used as a greeting) |

| Selamat jalan | /səlamat dʒalan/ | Have a safe journey (equivalent to "goodbye", used by the party staying) |

| Selamat tinggal | /səlamat tiŋɡal/ | Have a safe stay (equivalent to "goodbye", used by the party leaving) |

| Terima kasih | /tərima kasih/ | Thank you |

| Sama-sama | /samə samə/ | You are welcome |

| Selamat pagi | /səlamat paɡi/ | Good morning |

| Selamat petang | /səlamat pətaŋ/ | Good afternoon/evening (note that 'Selamat petang' must not be used at night as in English. Usually Indonesian say selamat sore or good afternoon from 3 PM to 5 PM and selamat petang is for 6 PM. |

| Selamat sejahtera | /səlamat sədʒahtərə/ | For a general greeting, use 'Selamat sejahtera') Greetings (formal). This greeting is rarely used however, and would be unheard of, especially in Singapore. Its usage might be awkward for the receiver. But it is still used in schools, as a greeting between students and teachers. |

| Selamat malam | /səlamat malam/ | Good night |

| Jumpa lagi | See you again | |

| Siapakah nama awak/kamu?/Nama kamu siapa? | What is your name? | |

| Nama saya ... | My name is ... (Followed immediately by the name: for example, if one's name was Munirah, then one would introduce oneself by saying "Nama saya Munirah", which translates to "My name is Munirah".) | |

| Apa khabar? | How are you? / What's up? (literally, "What news?") | |

| Khabar baik | Fine, (lit.good news) | |

| Saya sakit | I'm sick | |

| Ya | /jə/ | Yes |

| Tidak ("tak" colloquially) | No | |

| Aku (Saya) cinta kepadamu (awak) | I love you (romantic love. In romantic situations, use informal "aku" instead of "saya" for "I". And "kamu" or just "-mu" for "You". In romance, in immediate family communication and in songs, informal pronouns are used). In Malay language, appropriate personal pronouns must be used depending on (1) whether the situation is formal or informal, (2) the social status of the people around the speaker and (3) the relationship of the speaker with the person spoken to and/or with people around the speaker. For learners of Malay language, it is advised that they stick to formal personal pronouns when speaking Malay to Malays and Indonesians. The speaker risks being considered as rude if they use informal personal pronouns in inappropriate situations. | |

| Saya benci awak/kamu | I hate you | |

| Saya suka... | I like... | |

| Saya tidak faham/paham (or simply "tak faham" colloquially) | I do not understand (or simply "don't understand" colloquially) | |

| Saya tidak tahu (or "tak tau" colloquially) | I do not know (or "don't know" colloquially) | |

| (Minta) maaf | I apologise ('minta' is to request i.e. "do forgive") | |

| Tumpang/numpang tanya | "May I ask...?" (used when trying to ask something) | |

| Tolong | Help | |

| Apa | What | |

| Siapa | Who | |

| Bila / Kapan | When | |

| Bagaimana | How | |

| makan | Eat | |

| minum | Drink | |

| Tiada/tidak ada | Nothing, none, don't have |

See also

- Varieties of Malay

- Jawi, an Arabic alphabet for Malay

- Comparison of standard Malaysian and Indonesian

- Indonesian language

- Languages of Indonesia

- List of English words of Malay origin

- Malajoe Batawi

- Malaysian English, the English used formally in Malaysia.

- Malaysian language

References

- ↑ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ↑ Uli, Kozok (10 March 2012). "How many people speak Indonesian". University of Hawaii at Manoa. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

James T. Collins (Bahasa Sanskerta dan Bahasa Melayu, Jakarta: KPG 2009) gives a conservative estimate of approximately 200 million, and a maximum estimate of 250 million speakers of Malay (Collins 2009, p. 17).

- ↑ "Kedah MB defends use of Jawi on signboards". The Star. 26 August 2008. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Indonesian Archipelago Malay". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ 10 million in Malaysia, 5 million in Indonesia as "Malay" plus 250 million as "Indonesian", etc.

- ↑ K. Alexander Adelaar, "Where does Malay come from? Twenty years of discussions about homeland, migrations and classifications", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 160 (2004), No. 1, Leiden, pp. 1-30

- ↑ Andaya, Leonard Y (2001), "The Search for the 'Origins' of Melayu" (PDF), Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, University of Singapore, 32 (3), doi:10.1017/s0022463401000169

- ↑ Wurm, Stephen; Mühlhäusler, Peter; Tryon, Darrell T. (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas: Vol I: Maps. Vol II: Texts. Walter de Gruyter. p. 677. ISBN 978-3-11-081972-4.

- ↑ "Bahasa Melayu Kuno". Bahasa-malaysia-simple-fun.com. 15 September 2007. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ↑ Sneddon, James N. (2003). The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society. UNSW Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-86840-598-8.

- 1 2 Sneddon, James N. (2003). The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society. UNSW Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-86840-598-8.

- ↑ Ethnologue 16 classifies them as distinct languages, ISO3 kxd and meo, but states that they "are so closely related that they may one day be included as dialects of Malay".

- ↑ Malay (Bahasa Melayu). Retrieved 30 August 2008.

- ↑ "Malay Can Be 'Language Of Asean' | Local News". Brudirect.com. 24 October 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ↑ Salleh, Haji (2008). An introduction to modern Malaysian literature. Kuala Lumpur: Institut Terjemahan Negara Malaysia Berhad. pp. xvi. ISBN 978-983-068-307-2.

- ↑ "East Timor Languages". www.easttimorgovernment.com.

- 1 2 Clynes, Adrian; Deterding, David (12 July 2011). "Standard Malay (Brunei)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 41 (02): 259–268. doi:10.1017/S002510031100017X. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2014. .

- ↑ Soderberg, Craig D.; Olson, Kenneth S. (2008). "Indonesian". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 38 (2): 209–213. doi:10.1017/S0025100308003320. ISSN 1475-3502.

- ↑ Asmah Haji, Omar (1985). Susur galur bahasa Melayu. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- ↑ Ahmad, Zaharani (1993). Fonologi generatif: teori dan penerapan. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- ↑ Clynes, Adrian (1997). "On the Proto-Austronesian "Diphthongs"". Oceanic Linguistics. 36 (2): 347–361. doi:10.2307/3622989. JSTOR 3622989.

- ↑ Adelaar, K. A. (1992). Proto Malayic: the reconstruction of its phonology and parts of its lexicon and morphology (PDF). Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. doi:10.15144/pl-c119. ISBN 0858834081. OCLC 26845189.

Further reading

- Adelaar, K., "Where does Malay come from? Twenty years of discussions about homeland, migrations and classifications", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 160 (2004), no: 1, Leiden, 1-30

- Edwards, E. D., and C. O. Blagden. 1931. "A Chinese Vocabulary of Malacca Malay Words and Phrases Collected Between A. D. 1403 and 1511 (?)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London 6 (3). Cambridge University Press, School of Oriental and African Studies: 715–49.

- C. O. B. 1939. "Corrigenda and Addenda: A Chinese Vocabulary of Malacca Malay Words and Phrases Collected Between A. D. 1403 and 1511 (?)". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London 10 (1). Cambridge University Press.

- Vladimir Braginsky (18 March 2014). Classical Civilizations of South-East Asia. Routledge. pp. 366–. ISBN 978-1-136-84879-7.

External links

| Malay edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malay language. |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Malay. |

- Adelaar, K., "Where does Malay come from? Twenty years of discussions about homeland, migrations and classifications", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 160 (2004), no: 1, Leiden, 1-30

- The list of Malay words and list of words of Malay origin at Wiktionary, the free dictionary and Wikipedia's sibling project

- Swadesh list of Malay words

- Digital version of Wilkinson's 1926 Malay-English Dictionary

- Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu, online Malay language database provided by the Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka

- Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia dalam jaringan (Online Great Dictionary of the Indonesian Language published by Pusat Bahasa, in Indonesian only)

- Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (Institute of Language and Literature Malaysia, in Malay only)

- The Malay Spelling Reform, Asmah Haji Omar, (Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society, 1989-2 pp. 9–13 later designated J11)

- Malay Chinese Dictionary

- Malay English Dictionary

- Malay English Translation