Tocharians

"Tocharian donors", 6th-century AD fresco from the Kizil Caves | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

|

Tarim Basin in 1st millennium AD (modern Xinjiang, China) | |

| Languages | |

| Tocharian languages | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism and Manichaeism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Iranians, Afanasevo |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

The Tocharians or Tokharians (/təˈkɛəriənz/ or /təˈkɑːriənz/) were Indo-European peoples who inhabited the medieval oasis city-states on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China) in ancient times.

The Tocharian languages, a branch of the Indo-European family, are known from manuscripts from the 6th to 8th centuries AD. The name "Tocharian" was given to them by modern scholars, who identified their speakers with a people who inhabited Bactria from the 2nd century BC, and were known in ancient Greek sources as the Tókharoi (Latin Tochari). This identification is generally considered erroneous, but the name "Tocharian" remains the most common term for the languages and their speakers.

Agricultural communities first appeared in the oases of the northern Tarim circa 2000 BC. (The earliest Tarim mummies, which may not be connected to the Tocharians, date from c. 1800 BC.) Some scholars have linked these communities to the Afanasevo culture found earlier (c. 3500–2500 BC) in Siberia, north of the Tarim.

By the 2nd century BC, these settlements had developed into city states, overshadowed by nomadic peoples to the north and Chinese empires to the east. These cities, the largest of which was Kucha, also served as way stations on the branch of the Silk Road that ran along the northern edge of the Taklamakan desert.

From the 8th century AD, the Uyghurs – speakers of a Turkic language from the Kingdom of Qocho – settled in the region. The peoples of the Tarim city states intermixed with the Uyghurs, whose Old Uyghur language spread through the region. The Tocharian languages are believed to have become extinct during the 9th century.

Names

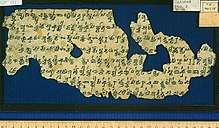

Around the beginning of the 20th century, archaeologists recovered a number of manuscripts from oases in the Tarim Basin written in two closely related but previously unknown Indo-European languages. Another text recovered from the same area, a Buddhist work in Old Turkic, included a colophon stating that the text had been translated from Sanskrit via a toxrï language, which Friedrich W. K. Müller guessed was one of the newly discovered languages.[1]

Müller called the languages "Tocharian" (German Tocharisch), linking this toxrï with the ethnonym Tókharoi (Ancient Greek: Τόχαροι, Ptolemy VI, 11, 6, 2nd century AD) applied by Strabo to one of the Scythian tribes that overran the Greco-Bactrian kingdom (present day Afghanistan-Pakistan) in the second half of the 2nd century BC.[lower-alpha 1] This term was itself derived from Indo-Iranian (cf. Old Persian tuxāri-, Khotanese ttahvāra, and Sanskrit tukhāra), the source of the term "Tokharistan" usually referring to 1st millennium Bactria, as well as the Takhar province of Afghanistan. The Tókharoi are often identified by modern scholars with the Yuezhi of Chinese historical accounts, who founded the Kushan Empire.[2][3] These people are now known to have spoken Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language that is quite distinct from the Tocharian languages, and Müller's identification is now a minority position among scholars. Nevertheless, "Tocharian" remains the standard term for the languages of the Tarim Basin manuscripts and for the people who produced them.[1][4]

The name of Kucha in Tocharian B was Kuśi, with adjectival form kuśiññe. The word may be derived from Proto-Indo-European *keuk "shining, white".[5] The Tocharian B word akeññe may have referred to people of Agni, with a derivation meaning "borderers, marchers".[6] One of the Tocharian A texts has ārśi-käntwā as a name for their own language, so that ārśi may have meant "Agnean", though "monk" is also possible.[7]

Languages

The Tocharian languages are known from around 7600 documents dating from about 400 to 1200 AD, found at 30 sites in the northeast Tarim area.[8] The manuscripts are written in two distinct, but closely related, Indo-European languages, conventionally known as Tocharian A and Tocharian B.[9]

Tocharian A (Agnean or East Tocharian) was found in the northeastern oases known to the Tocharians as Ārśi, later Agni (i.e. Chinese Yanqi; modern Karasahr) and Turpan (including Khocho or Qočo; known in Chinese as Gaochang). Some 500 manuscripts have been studied in detail, mostly coming from Buddhist monasteries. Many authors take this to imply that Tocharian A had become a purely literary and liturgical language by the time of the manuscripts, but it may be that the surviving documents are unrepresentative.[10]

Tocharian B (Kuchean or West Tocharian) was found at all the Tocharian A sites and also in several sites further west, including Kuchi (later Kucha). It appears to have still been in use in daily life at that time.[11] Over 3200 manuscripts have been studied in detail.[10]

The languages had significant differences in phonology, morphology and vocabulary, making them mutually unintelligible.[12][13] Tocharian A shows innovations in the vowels and nominal inflection, whereas Tocharian B has changes in the consonants and verbal inflection. Many of the differences in vocabulary between the languages concern Buddhist concepts, which may suggest that they were associated with different Buddhist traditions.[12]

The differences indicate that they diverged from a common ancestor between 500 and 1000 years before the earliest documents, that is, some time in the 1st millennium BC.[14] Common Indo-European vocabulary retained in Tocharian includes words for herding, cattle, sheep, pigs, dogs, horses, textiles, farming, wheat, gold, silver, and wheeled vehicles.[15]

Prakrit documents from 3rd century Krorän, Andir and Niya on the southeast edge of the Tarim Basin contain around 100 loanwords and 1000 proper names that cannot be traced to an Indic or Iranian source.[16] Thomas Burrow suggested that they come from a variety of Tocharian, dubbed Tocharian C or Kroränian, which may have been spoken by at least some of the local populace.[17] Burrow's theory is widely accepted, but the evidence is meagre and inconclusive, and some scholars favour alternative explanations.[8]

Settlement of the Tarim basin

The Taklamakan Desert is roughly oval in shape, about 1,000 km long and 400 km wide, surrounded on three sides by high mountains. The main part of the desert is sandy, surrounded by a belt of gravel desert.[18] The desert is completely barren, but in the late spring the melting snows of the surrounding mountains feed streams, which have been altered by human activity to create oases with mild microclimates and supporting intensive agriculture.[18] On the northern edge of the basin, these oases occur in small valleys before the gravels.[18] On the southern edge, they occur in alluvial fans on the edge of the sand zone. Isolated alluvial fan oases also occur in the gravel deserts of the Turpan Depression to the east of the Taklamakan.[19] From around 2000 BC, these oases supported Bronze Age settled agricultural communities of steadily increasing sophistication.[20]

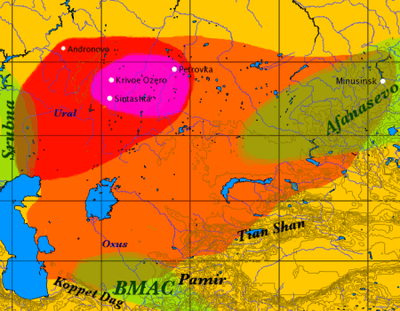

The necessary irrigation technology was first developed during the 3rd millennium BC in the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) to the west of the Pamir mountains, but it is unclear how it reached the Tarim.[21][22] The staple crops, wheat and barley, also originated in the west.[23] J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair argue that the Tarim was first settled by Tocharian-speakers from the Afanasevo culture to the north, who occupied the northern and eastern edges of the basin. The Afanasevo culture (c. 3500–2500 BC) displays cultural and genetic connections with the Indo-European-associated cultures of the Central Asian steppe yet predates the specifically Indo-Iranian-associated Andronovo culture (c. 2000–900 BC) enough to account for the isolation of the Tocharian languages from Indo-Iranian linguistic innovations like satemization.[24]

The oldest of the Tarim mummies, bodies preserved by the desert conditions, date from 2000 BC and were found on the eastern edge of the Tarim basin. They seem to be Caucasoid types with light-colored hair.[25] A genetic study of remains from the oldest layer of the Xiaohe Cemetery found that the maternal lineages were a mixture of east and west Eurasian types, while all the paternal lineages were of west Eurasian type.[26] It is unknown whether they are connected with the frescoes painted at Tocharian sites more than two millennia later, which also depict light eyes and hair color.

Later, groups of nomadic pastoralists moved from the steppe into the grasslands to the north and northeast of the Tarim. They were the ancestors of peoples later known to Chinese authors as the Wusun and Yuezhi.[27] At least some of them spoke Iranian languages,[27] but a minority of scholars suggest that the Yuezhi were Tocharian speakers.[28][29]

During the 1st millennium BC, a further wave of immigrants, the Saka speaking Iranian languages, arrived from the west and settled along the southern rim of the Tarim.[30] They are believed to be the source of Iranian loanwords in Tocharian languages, particularly related to commerce and warfare.[31]

Oasis states

.svg.png)

The first record of the oasis states is found in Chinese histories. The Book of Han lists 36 statelets in the Tarim basin in the last two centuries BC.[32] These oases served as waystations on the trade routes forming part of the Silk Road passing along the northern and southern edges of the Taklamakan desert.[33] The largest were Kucha with 81,000 inhabitants and Agni (Yanqi or Karashar) with 32,000.[34] Chinese histories give no evidence of ethnic changes in these cities between that time and the period of the Tocharian manuscripts from these sites.[35] Situated on the northern edge of the Tarim, these small urban societies were overshadowed by nomadic peoples to the north and Chinese empires to the east. They conceded tributary relations with the larger powers when required, and acted independently when they could.[36]

Xiongnu and Han empire

In 177 BC, the Xiongnu drove the Yuezhi from western Gansu, causing most of them to flee west to the Ili Valley and then to Bactria. The Xiongnu then overcame the Tarim statelets, which became a vital part of their empire.[37] The Chinese Han dynasty determined to weaken their Xiongnu enemies by depriving them of this area.[38] This was achieved in a series of campaigns beginning in 108 BC and culminating in the establishment of the Protectorate of the Western Regions in 60 BC.[39] The Han government used a range of tactics, including plots to assassinate local rulers, direct attacks on a few states (e.g. Kucha in 65 BC) to cow the rest, and the massacre of the population of Luntai (80 km east of Kucha) when they resisted.[40] The Han controlled the Tarim states intermittently until their final withdrawal in 150 AD.[41][42]

Flourishing of the oasis states

Kucha, the largest of the oasis cities, was ruled by the Bai family, sometimes autonomously and sometimes as vassals of outside powers.[43] The government included some 30 named posts below the king, with all but the highest-ranking titles occurring in pairs of left and right. Other states had similar structures, though on a smaller scale.[44] The Book of Jin says of the city:

They have a walled city and suburbs. The walls are threefold. Within are Buddhist temples and stupas numbering a thousand. The people are engaged in agriculture and husbandry. The men and women cut their hair and wear it at the neck. The prince's palace is grand and imposing, glittering like an abode of the gods.

The inhabitants grew red millet, wheat, rice, legumes, hemp, grapes and pomegranates, and reared horses, cattle, sheep and camels.[46] They also extracted a wide range of metals and minerals from the surrounding mountains.[47] Handicrafts included leather goods, fine felts and rugs.[47]

The Kushan Empire expanded into the Tarim during the 2nd century, bringing Buddhism, Kushan art, Sanskrit as a liturgical language and Prakrit as an administrative language (in the southern Tarim states).[48] With these Indic languages came scripts, including the Brahmi script (later adapted to write Tocharian) and the Kharosthi script.[49]

From the 3rd century, Kucha became a centre of Buddhist studies. Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese by Kuchean monks, the most famous of whom was Kumārajīva (344–412/5).[50][41] Captured by Lü Guang of the Later Liang in an attack on Kucha in 384, Kumārajīva learned Chinese during his years of captivity in Gansu. In 401, he was brought to the Later Qin capital of Chang'an, where he remained as head of a translation bureau until his death in 413.[45][51]

The Kizil Caves lie 65 km west of Kucha, and contain over 236 Buddhist temples. Their murals date from the 3rd to the 8th century.[52] Many of these murals were removed by Albert von Le Coq and other European archaeologists in the early 20th century, and are now held in European museums, but others remain in their original locations.[53]

An increasingly dry climate in the 4th and 5th centuries led to the abandonment of several of the southern cities, including Niya and Krorän, with a consequent shift of trade from the southern route to the northern one.[54] Confederations of nomadic tribes also began to jostle for supremacy. The northern oasis states were conquered by Rouran in the late 5th century, leaving the local leaders in place. The Rouran were replaced in the mid-6th century by the Turks, who then split into western and eastern khaganates. The Bai family continued to rule Kucha, as vassals of the Western Turks[55] The oldest surviving texts in Tocharian date from this period, and deal with a wide variety of administrative, religious and everyday topics.[56] They also include travel passes, small slips of poplar wood giving the size of the permitted caravans for officials at the next station along the road.[57]

Tang conquest and aftermath

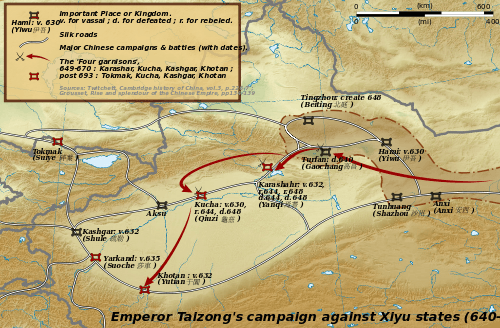

In the 7th century, Emperor Taizong of Tang China, having overcome the Eastern Turks, sent his armies west to attack the Western Turks and the oasis states.[58] The first oasis to fall was Turfan, which was captured in 630 and annexed as part of China.[59]

Next to the west lay the city of Agni, which had been a tributary of the Tang since 632. Alarmed by the nearby Chinese armies, Agni stopped sending Tribute to China and formed an alliance with the Western Turks. They were aided by Kucha, who also stopped sending tribute. The Tang captured Agni in 644, defeating a Western Turk relief force, and made the king resume tribute. When that king was deposed by a relative in 648, the Tang sent an army under the Turk general Ashina She'er to install a compliant member of the local royal family.[60] Ashina She'er continued to capture Kucha, and made it the headquarters of the Tang Protectorate General to Pacify the West. Kuchean forces recaptured the city and killed protector-general, Guo Xiaoke, but it fell again to Ashina She'er, who had 11,000 of the inhabitants executed in reprisal for the killing of Guo.[61] The Tocharian cities never recovered from the Tang conquest.[62]

The Tang lost the Tarim basin to the Tibetan Empire in 670, but regained it in 692, and continued to rule there until it was recaptured by the Tibetans in 792.[63] The ruling Bai family of Kucha are last mentioned in Chinese sources in 787.[64] There is little mention of the region in Chinese sources for the 9th and 10th centuries.[65]

The Uyghur Khaganate took control of the northern Tarim in 803. After their capital in Mongolia was sacked by the Kirghiz in 840, they established a new state, the Kingdom of Qocho with its capital at Gaochang (near Turfan) in 866.[66] Over centuries of contact and intermarriage, the cultures and populations of the pastoralist rulers and their agriculturalist subjects blended together.[67] The Uighurs abandoned their state religion of Manichaeism in favour of Buddhism, and adopted the agricultural lifestyle and many of the customs of the oasis-dwellers.[68] The Tocharian language gradually disappeared as the urban population switched to the Old Uyghur language.[69]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Most of the Scythians, beginning from the Caspian Sea, are called Dahae Scythae, and those situated more towards the east Massagetae and Sacae; the rest have the common appellation of Scythians, but each separate tribe has its peculiar name. All, or the greatest part of them, are nomads. The best known tribes are those who deprived the Greeks of Bactriana, the Asii, Pasiani, Tochari, and Sacarauli, who came from the country on the other side of the Iaxartes, opposite the Sacae and Sogdiani" (Strabo, 11-8-2)

References

- 1 2 Tocharian Online: Series Introduction Archived 2015-06-29 at the Wayback Machine., Todd B. Krause and Jonathan Slocum, University of Texas as Austin.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 270–297.

- ↑ Beckwith (2009), pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Mallory & Adams (1997), p. 509.

- ↑ Adams (2013), p. 198.

- ↑ Adams (2013), pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Adams (2013), p. 57.

- 1 2 Mallory (2015), pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Winter (1998), p. 154.

- 1 2 Mallory (2015), p. 4.

- ↑ Kim, Ronald (2012). "Introduction to Tocharian" (PDF). p. 30.

- 1 2 Winter (1998), p. 155.

- ↑ Mallory (2015), p. 7.

- ↑ Mallory (2015), pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Mallory (2015), pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 277–278.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 278–279.

- 1 2 3 Chen & Hiebert (1995), p. 247.

- ↑ Chen & Hiebert (1995), p. 248.

- ↑ Chen & Hiebert (1995), pp. 250–272.

- ↑ Chen & Hiebert (1995), p. 245.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 262, 269.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 269.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 294–296, 317–318.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Li et al. (2010).

- 1 2 Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 318.

- ↑ John E. Hill (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome. Booksurge Publishing. p. 311. ISBN 1-4392-2134-0.

- ↑ Beckwith (2009), pp. 84, 380–383.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 268, 318.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 310–311, 318.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 66.

- ↑ Millward (2007), p. 6.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 68, 72.

- ↑ Mallory & Adams (1997), p. 591.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 72.

- ↑ Yü (1986), pp. 405, 407.

- ↑ Yü (1986), p. 407.

- ↑ Yü (1986), pp. 409–411.

- ↑ Loewe (1979), p. 49.

- 1 2 Hansen (2012), p. 66.

- ↑ Millward (2007), pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), pp. 66, 75.

- ↑ Di Cosmo (2000), p. 398.

- 1 2 Millward (2007), p. 28.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 73.

- 1 2 Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 74.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 97.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 115.

- ↑ Walter (1998), pp. 5–9.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), p. 68.

- ↑ Walter (1998), pp. 21–17.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), pp. 61–65.

- ↑ Millward (2007), p. 26.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), p. 75.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), p. 76.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), p. 77.

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), p. 220.

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), p. 225.

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), p. 226.

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), pp. 226, 228.

- ↑ Wechsler (1979), p. 228.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), p. 80.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 272.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), pp. 272–273.

- ↑ Hansen (2012), p. 108.

- ↑ Millward (2007), p. 48.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 101.

- ↑ Mallory & Mair (2000), p. 273.

- Adams, Douglas Q. (2013), A Dictionary of Tocharian B (2nd ed.), Rodopi, ISBN 978-90-420-3671-0.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009), Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Asia from the Bronze Age to the Present, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-15034-5.

- Chen, Kwang-tzuu; Hiebert, Fredrik T. (1995), "The late prehistory of Xinjiang in relation to its neighbors", Journal of World Prehistory, 9 (2): 243–300, doi:10.1007/bf02221840, JSTOR 25801077.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2000), "Ancient city-states of the Tarim Basin", in Hansen, Mogens Herman, A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures, Copenhagen: Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, pp. 393–407, ISBN 978-87-7876-177-4.

- Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-195-15931-8.

- Li, Chunxiang; Li, Hongjie; Cui, Yinqiu; Xie, Chengzhi; Cai, Dawei; Li, Wenying; Mair, Victor H.; Xu, Zhi; Zhang, Quanchao; Abuduresule, Idelis; Jin, Li; Zhu, Hong; Zhou, Hui (2010), "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age", BMC Biology, 8 (15), doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-15, PMC 2838831, PMID 20163704.

- Loewe, Michael (1979), "Introduction", in Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus, China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 BC – AD 23, Brill, pp. 1–70, ISBN 978-90-04-05884-2.

- Mallory, J.P. (2015), "The problem of Tocharian origins: an archaeological perspective" (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers (259).

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Mallory, J.P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000), The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-05101-6.

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- Walter, Mariko Namba (1998), "Tocharian Buddhism in Kucha: Buddhism of Indo-European Centum Speakers in Chinese Turkestan before the 10th Century C.E." (PDF), Sino-Platonic Papers, 85.

- Wechsler, Howard J. (1979), "T'ai-tsung (reign 624–49) the consolidator", in Twitchett, Denis, Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part 1, The Cambridge History of China, 3, Cambridge University Press, pp. 188–241, ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Winter, Werner (1998), "Tocharian", in Ramat, Giacalone Anna; Ramat, Paolo, The Indo-European languages, London: Routledge, pp. 154–168, ISBN 978-0-415-06449-1.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986), "Han foreign relations", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C.–A.D. 220, The Cambridge History of China, 1, Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–462, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

Further reading

Note: Recent discoveries have rendered obsolete some of René Grousset's classic The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, published in 1939, which, however, still provides a broad background against which to assess more modern detailed studies.

- Baldi, Philip. 1983. An Introduction to the Indo-European Languages. Carbondale. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland. 1999. The Mummies of Ürümchi. London. Pan Books.

- Beekes, Robert. 1995. Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. Philadelphia. John Benjamins.

- Hemphill, Brian E. and J.P. Mallory. 2004. "Horse-mounted invaders from the Russo-Kazakh steppe or agricultural colonists from Western Central Asia? A craniometric investigation of the Bronze Age settlement of Xinjiang" in American Journal of Physical Anthropology vol. 125 pp 199ff.

- Lane, George S. 1966. "On the Interrelationship of the Tocharian Dialects," in Ancient Indo-European Dialects, eds. Henrik Birnbaum and Jaan Puhvel. Berkeley. University of California Press.

- Walter, Mariko Namba 1998 "Tocharian Buddhism in Kucha: Buddhism of Indo-European Centum Speakers in Chinese Turkestan before the 10th Century C.E." Sino-Platonic Papers 85.

- Xu, Wenkan 1995 "The Discovery of the Xinjiang Mummies and Studies of the Origin of the Tocharians" The Journal of Indo-European Studies, Vol. 23, Number 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 1995, pp. 357–369.

- Xu, Wenkan 1996 "The Tokharians and Buddhism" In: Studies in Central and East Asian Religions 9, pp. 1–17.

External links

- Tocharian alphabet at omniglot.com

- Tocharian alphabet

- Modern studies are developing a Tocharian dictionary.

- Mark Dickens, 'Everything you always wanted to know about Tocharian'.

- A dictionary of Tocharian B by Douglas Q. Adams (Leiden Studies in Indo-European 10), xxxiv, 830 pp., Rodopi: Amsterdam – Atlanta, 1999.

- Žhivko Voynikov (Bulgaria). SOME ANCIENT CHINESE NAMES IN EAST TURKESTAN AND CENTRAL ASIA AND THE TOCHARIAN QUESTION