Yazidis

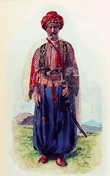

Yazidis on the mountain of Sinjar, Iraqi–Syrian border, 1920s. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 500,000–1,200,000[1][2][3] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 650,000[4] | |

| 100,000–120,000[5][6][7] | |

| 70,000[8][9] | |

| 40,586 (2010 census)[10] | |

| 35,272 (2011 census)[11] | |

| 12,174 (2014 census)[12] | |

| 7,000[7] | |

| 118 (2011 census)[13] | |

| 45 (2009 census)[14] | |

| 16 (2015 census)[15] | |

| 15 (2016 census)[12] | |

| 4 (2018 official statistics)[16] | |

| 1 (2015 census)[17] | |

| Religions | |

| Yazidism[18]:196 | |

| Languages | |

| Northern Kurdish (Latin script)[19] | |

| Yazidism | |

|---|---|

| Type | Syncretic |

| Classification | Ethnoreligious group |

| Mir | Tahseen Said |

| Baba Sheikh | Khurto Hajji Ismail |

| Headquarters | Ain Sifni |

| Other name(s) | Êzidî, Yazdani |

The Yazidis, or Yezidis (/jəˈziːdiːz/ (![]()

The Yazidis are monotheists,[36]:71[43][44][45] believing in God as creator of the world, which he has placed under the care of seven holy beings or angels, the chief of whom is Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel. The Peacock Angel, as world-ruler, causes both good and bad to befall individuals, and this ambivalent character is reflected in myths of his own temporary fall from God's favour, before his remorseful tears extinguished the fires of his hellish prison and he was reconciled with God.[46]

This belief has been linked by some people to Sufi mystical reflections on Iblis, who also refused to prostrate to Adam, despite God's express command to do so.[47] Because of this similarity to the Sufi tradition of Iblis, some followers of other monotheistic religions of the region identify the Peacock Angel with their own unredeemed evil spirit Satan,[48]:29[36] which has incited centuries of persecution of the Yazidis as "devil worshippers".[49][50] Persecution of Yazidis has continued in their home communities within the borders of modern Iraq, under fundamentalist Sunni Muslim revolutionaries.[51]

Beginning in August 2014, the Yazidis were targeted by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in its campaign to rid Iraq and its neighbouring countries of non-Islamic influences.[52]

Demographics

Historically, the Yazidis lived primarily in communities located in present-day Iraq, Turkey, and Syria and also had significant numbers in Armenia, Georgia, and Iran. However, events since the end of the 20th century have resulted in considerable demographic shift in these areas as well as mass emigration.[7] As a result, population estimates are unclear in many regions, and estimates of the size of the total population vary.[1]

Iraq

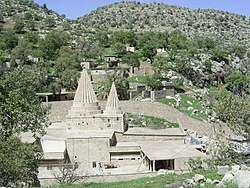

The majority of the Yazidi population lives in Iraq, where they make up an important minority community.[1] Estimates of the size of these communities vary significantly, between 70,000 and 500,000. They are particularly concentrated in northern Iraq in the Nineveh Province. The two biggest communities are in Shekhan, northeast of Mosul and in Sinjar, at the Syrian border 80 kilometres (50 mi) west of Mosul. In Shekhan is the shrine of Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir at Lalish. In the early 1900s most of the settled population of the Western Desert were Yazidi.[53] During the 20th century, the Shekhan community struggled for dominance with the more conservative Sinjar community.[1] The demographic profile has probably changed considerably since the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003 and the fall of Saddam Hussein's government.[1]

_10.jpg)

According to the Human Rights Watch, Yazidis were under the Arabisation process of Saddam Hussein between 1970 and 2003. In 2009, some Yazidis who had previously lived under the Arabisation process of Saddam Hussein complained about the political tactics of the Kurdistan Regional Government that were intended to make Yazidis identify themselves as Kurds.[54][55] A report from Human Rights Watch (HRW), in 2009, declares that to incorporate disputed territories in northern Iraq—particularly the Nineveh province—into the Kurdish region, the KDP authorities had used KRG's political and economical resources to make Yazidis identify themselves as Kurds. The HRW report also criticises heavy-handed tactics."[56]

While geographically located in Kurdish regions, Yazidi do not self-identify as Kurdish.[57] There has been a dispute as to whether Yazidi are Kurdish.[36]:48[58]:219[59] Additionally, the Soviet Union considered the Yazidis to be Kurds, as does Sharaf Khan Bidlisi's Sheref-nameh of 1597, which cites seven of the Kurdish tribes as being at least partly Yazidi, and Kurdish tribal confederations as containing substantial Yazidi sections.[60] Modern Yazidi communities disagree with this classification.

According to the UNCHR reports, it is disputed, even among the community itself as well as among Kurds, whether Yazidis are ethnically Kurds or form a distinct ethnic group.[61]

The Yazidis' cultural practices are observably Kurdish, and almost all speak Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish).[62]

Syria

Yazidis in Syria live primarily in two communities, one in the Al-Jazira area and the other in the Kurd-Dagh.[1] Population numbers for the Syrian Yazidi community are unclear. In 1963, the community was estimated at about 10,000, according to the national census, but numbers for 1987 were unavailable.[63] There may be between about 12,000 and 15,000 Yazidis in Syria today,[1][64] though more than half of the community may have emigrated from Syria since the 1980s.[7] Estimates are further complicated by the arrival of as many as 50,000 Yazidi refugees from Iraq during the Iraq War.[7]

Georgia

The Yazidi population in Georgia has been dwindling since the 1990s, mostly due to economic migration to Russia and the West. According to a census carried out in 1989, there were over 30,000 Yazidis in Georgia; according to the 2002 census, however, only around 18,000 Yazidis remained in Georgia. However, by other estimates, the community fell from around 30,000 people to fewer than 5,000 during the 1990s.[7] Today they number as little 6,000 by some estimates, including recent refugees from Sinjar in Iraq, who fled to Georgia following persecution by ISIL.[65] On 16 June 2015, Yazidis celebrated the opening of a temple and a cultural centre named after Sultan Ezid in Varketili, a suburb of Tbilisi. This is the third such temple in the world after those in Iraqi Kurdistan and Armenia.[65]

Armenia

According to the 2011 census, there are 35,272 Yazidis in Armenia, making them Armenia's largest ethnic minority group.[66] Ten years earlier, in the 2001 census, 40,620 Yazidis were registered in Armenia.[67] They form majority in Armavir province of Armenia.[68]Media have estimated the number of Yazidis in Armenia to be between 30,000 and 50,000. Most of them are the descendants of refugees who fled to Armenia in order to escape the persecution that they had previously suffered during Ottoman rule, including a wave of persecution which occurred during the Armenian Genocide, when many Armenians found refuge in Yazidi villages.[69]

There is a Yazidi temple, called Ziarat in the village of Aknalich in the region of Armavir. Construction on a new Yazidi temple in Aknalich, called "Quba Mere Diwan," is underway. The temple is slated to become the largest Yazidi temple in the world and is privately funded by Mirza Sloian, a Yazidi businessman based in Moscow who is originally from the Armavir region.[70]

Turkey

The Kurdish Yazidi community of Turkey declined precipitously during the 20th century. By 1982, the community had decreased to about 30,000, and in 2009 there were fewer than 500. Most of them have immigrated to Europe, particularly Germany; those who remain reside primarily in their former heartland of Tur Abdin.[1]

Western Europe

This mass emigration has resulted in the establishment of large Yazidi diaspora communities abroad. The most significant of these is in Germany, which now has a Yazidi community of more than 100,000 living primarily in Hannover, Bielefeld, Celle, Bremen, Bad Oeynhausen, Pforzheim and Oldenburg.[39] Most are from Turkey and, more recently, Iraq and live in the western states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Lower Saxony.[1] Since 2008, Sweden has seen sizeable growth in its Yazidi emigrant community, which had grown to around 4,000 by 2010,[7] and a smaller community exists in the Netherlands.[1] Other Yazidi diaspora groups live in Belgium, Denmark, France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Australia; these have a total population of probably less than 5,000.[1]

Feleknas Uca, a Yazidi Member of the European Parliament for Germany's Party of Democratic Socialism, was the world's only Yazidi parliamentarian until the Iraqi legislature was elected in 2005. European Yazidis have contributed to the academic community, such as Khalil Rashow in Germany and Jalile Jalil in Austria.

In May 2012, four members of a Yazidi family living in Detmold, Germany were convicted for having murdered their sister in a so-called "honour killing" and sentenced to terms ranging from four-and-a-half years to life in prison. The victim was 18-year-old Arzu Özmen (also spelled Ozmen outside Germany), who fell in love with a German journeyman baker and ran away from her family, violating the exogamy taboo. In November 2011, her siblings abducted her, and brother Osman killed her with two shots in the head.[71]

Origins

The Yazidi people speak Kurmanji Kurdish[59] and adhere to the religion Yazidism. Their cultural practices are observed in Kurdish, which is also the language of almost all the orally transmitted religious traditions of the Yazidis.[72] Although the Yazidis speak mostly in Kurdish, their exact origin is a matter of dispute among scholars, even among the community itself as well as among Kurds, whether they are ethnically Kurds or form a distinct ethnic group.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81] In Armenia, the Yazidis are recognized as a distinct ethnic group.[82][83][84]

The Yazidis' own name for themselves is Êzidî or Êzîdî or, in some areas, Dasinî (the latter, strictly speaking, is a tribal name). Western scholars derive the name from the Umayyad Caliph Yazīd ibn Muʿāwiya (Yazid I), who is revered by Yazidis as Sultan Ezi.[85] Earlier scholars and many Yazidis derive it from Old Iranian yazata, Middle Persian yazad 'divine being'.[86]

One of the important figures of Yazidism is 'Adī ibn Musafir, who is said to be of Umayyad descent. Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir settled in the valley of Laliş (some 58 kilometres (36 mi) northeast of Mosul) in the Yazidi mountains in the early 12th century and founded the 'Adawiyya Sufi order. He died in 1162, and his tomb at Laliş is a focal point of Yazidi pilgrimage and the principal Yazidi holy site.[87] Yazidism has many influences: Sufi influence and imagery can be seen in the religious vocabulary, especially in the terminology of the Yazidis' esoteric literature, but much of the theology is non-Islamic. Its cosmogony apparently has many points in common with those of ancient Iranian religions blended with elements of pre-Islamic ancient Mesopotamian religious traditions and Zoroastrianism.[32] It is also believed that Yazidism is a branch of Yazdânism, the pre-Islamic, native religion of the Kurds. Early writers attempted to describe Yazidi origins, broadly speaking, in terms of Islam, or Persian, or sometimes even "pagan" religions; however, research published since the 1990s has shown such an approach to be simplistic.[1] The origin of Yazidism is now usually seen by scholars as a complex process of syncretism, whereby the belief system and practices of a local faith had a profound influence on the religiosity of adherents and caused it to deviate from Islamic norms relatively soon after the death of its founder.

Another theory of Yazidi origins is given by the Persian scholar Al-Shahrastani. According to Al-Shahrastani, the Yezidis are the followers of Yezîd bn Unaisa, who kept friendship with the first Muhakkamah before the Azariḳa. The first Muhakkamah is an appellative applied to the Muslim schismatics called Al-Ḫawarij. Accordingly, it might be inferred that the Yezidis were originally a Ḫarijite sub-sect. Yezid bn Unaisa moreover, is said to have been in sympathy with the Ibadis, a sect founded by 'Abd-Allah Ibn Ibaḍ."[88]

Genetics

Modern-day Assyrians and Yazidis from Northern Iraq have a stronger genetic continuity with the original Mesopotamian people. The northern Iraqi Syriac and Yazidi populations were found in the middle of a genetic continuum between the Near East and Southeastern Europe.[89]

Religious beliefs

Yazidis are monotheists,[43] believing in one God, who created the world and entrusted it into the care of a Heptad of seven Holy Beings, often known as Angels or heft sirr (the Seven Mysteries). The names of these beings or angels are Azaz'il, Gabra'il (Jabra'il), Mikha'il, Rafa'il (Israfil), Dadra'il, Azrafil and Shamkil (Shemna'il) [90] Preeminent among these is Tawûsê Melek (frequently known as "Melek Taus" in English publications), the Peacock Angel[91][51] (identified with one of these Angels). Tawûsê Melek is often identified by Christians and Muslims with Satan. According to claims in Encyclopedia of the Orient,

The reason for the Yazidis' reputation of being devil worshipers is connected to the other name of Melek Taus, Shaytan, the same name the Koran has for Satan.[92]

Yazidis, however, believe Tawûsê Melek is not a source of evil or wickedness. They consider him to be the leader of the archangels, not a fallen angel.[48][36]

The Yazidis of Kurdistan have been called many things, most notoriously 'devil-worshippers,' a term used both by unsympathetic neighbours and fascinated Westerners. This sensational epithet is not only deeply offensive to the Yazidis themselves, but quite simply wrong."[93] Non-Yazidis have associated Melek Taus with Shaitan (Islamic/Arab name) or Satan, but Yazidis find that offensive and do not actually mention that name.[93]

Tawûsê Melek, the Peacock Angel

The Yazidis believe in a divine triad, like the Alawites.[94]:3 The original god of the Yazidis is considered to be remote and inactive in relation to his creation.[95] His first emanation is Tawûsê Melek, who functions as the ruler of the world. The second hypostasis of this trinity is Sheikh Adî. The third is Sultan Ezid. These are the three hypostases of the one God. The identity of these three is sometimes blurred, with Sheikh Adî considered to be a manifestation of Tawûsê Melek and vice versa. The same also applies to Sultan Ezid. Besides the triad, the second peculiar feature of Yazidi belief is the similarity between Tawûsê Melek and the Abrahamic Satan (the Islamic Iblīs). A popular Yazidi story narrates the fall of Tawûsê Melek and his subsequent rejection by humanity, with the exception of the Yazidis.[94]:21–22

The Kitêba Cilwe "Book of Illumination", which claims to be the words of Tawûsê Melek, and which presumably represents Yazidi belief, states that he allocates responsibilities, blessings, and misfortunes as he sees fit and that it is not for the race of Adam to question him. Sheikh Adî believed that the spirit of Tawûsê Melek was the same as his own, perhaps as a reincarnation. He is reported to have said:

I was present when Adam was living in Paradise, and also when Nemrud threw Abraham in fire. I was present when God said to me: 'You are the ruler and Lord on the Earth'. God, the compassionate, gave me seven earths and throne of the heaven.

Yazidi accounts of creation differ from that of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. They believe that God first created Tawûsê Melek from his own (God's) illumination (Ronahî) and the other six archangels were created later. God ordered Tawûsê Melek not to bow to other beings. Then God created the other archangels and ordered them to bring him dust (Ax) from the Earth (Erd) and build the body of Adam. Then, God gave life to Adam from his own breath and instructed all archangels to bow to Adam. The archangels obeyed except for Tawûsê Melek. In answer to God, Tawûsê Melek replied, "How can I submit to another being! I am from your illumination while Adam is made of dust." Then, God praised him and made him the leader of all angels and his deputy on the Earth. (This probably furthers what some see as a connection to the Islamic Shaytan, as according to the Quran, he too refused to bow to Adam at God's command, though in this case it is seen as being a sign of Shaytan's sinful pride.) Hence, the Yazidis believe that Tawûsê Melek is the representative of God on the face of the Earth and comes down to the Earth on the first Wednesday of Nisan (April). Yazidis hold that God created Tawûsê Melek on this day and celebrate it as New Year's Day. Yazidis argue that the order to bow to Adam was only a test for Tawûsê Melek, since if God commands anything then it must happen. (Bibe, dibe). In other words, God could have made him submit to Adam, but gave Tawûsê Melek the choice as a test. They believe that their respect and praise for Tawûsê Melek is a way to acknowledge his majestic and sublime nature. This idea is called "Knowledge of the Sublime" (Zanista Ciwaniyê). Şêx Adî has observed the story of Tawûsê Melek and believed in him.[96]

Descendants of Adam

One of the key creation beliefs held by Yazidis is that they are the descendants of Adam through his son Shehid bin Jer rather than Eve.[92] The Yazidis believe that before Adam and Eve copulated with each other for the first time, Tawûsê Melek encouraged them to see if they could reproduce on their own. He had the couple place their reproductive fluids in jars and store them for several months. When each jar was opened several months later, Eve's was found to contain vermin and insects, and Adam's was found to have contained a beautiful baby boy, Shehid bin Jer.[97] This lovely child, known as son of Jar grew up to marry a houri and became the ancestor of the Yazidis. Therefore, the Yazidis regard themselves as descending from Adam alone, while other humans are descendants of both Adam and Eve.[98][94]:33 This is the reason given for Yazidis being exclusively endogamous; clans do not intermarry with non-Yazidis and accept no converts to Yazidism. A severe punishment for breaking this rule is expulsion, which is also effectively excommunication as the soul of the exilee is forfeit.

Reincarnation

A belief in the reincarnation of lesser Yazidi souls also exists. Like the Ahl-e Haqq, the Yazidis use the metaphor of a change of garment to describe the process, which they call kiras guhorîn in Kurmanji (changing the garment). Spiritual purification of the soul can be attained via continual reincarnation within the faith group, but it can also be halted by means of expulsion from the Yazidi community; this is the worst possible fate, since the soul's spiritual progress halts and conversion back into the faith is impossible.[35] Alongside this notion of continuous rebirth, Yazidi theology also includes descriptions of heaven and hell, with hell extinguished, and other traditions incorporating these ideas into a belief system that includes reincarnation.[92]

Yazidi holy texts

The Yazidi holy books are claimed to be the Kitêba Cilwe (Book of Revelation) and the Mishefa Reş (Black Book). However, scholars generally agree that the manuscripts of both books published in 1911 and 1913 were forgeries written by non-Yazidis in response to Western travellers' and scholars' interest in the Yazidi religion; the material in them is consistent with authentic Yazidi traditions, however.[85] True texts of those names may have existed, but remain obscure. The real core texts of the religion that exist today are the hymns known as qawls; they have also been orally transmitted during most of their history, but are now being collected with the assent of the community, effectively transforming Yazidism into a scriptural religion.[85] The qawls are full of cryptic allusions and usually need to be accompanied by čirōks or 'stories' that explain their context.[85]

Organisation

Yazidi society is hierarchical. The secular leader of the world's Yazidi is a hereditary emir or prince, and the current emir is Prince Tahseen Said.[99] A chief sheikh, the Baba Sheikh, heads the religious hierarchy of the Yazidis, and the current Sheikh is Khurto Hajji Ismail.[100] The Yazidis are strictly endogamous; members of the three Yazidi castes, the murids, sheikhs, and pirs, marry only within their group. Marriage outside the caste is considered a sin punishable by death to restore lost honour.[26]

Religious practices

Prayers

Yazidis have five daily prayers:[97]

Nivêja berîspêdê (the Dawn Prayer), Nivêja rojhilatinê (the Sunrise Prayer), Nivêja nîvroyê (the Noon Prayer), Nivêja êvarî (the Afternoon Prayer), Nivêja rojavabûnê (the Sunset Prayer). However, most Yezidis observe only two of these, the sunrise and sunset prayers.

Worshipers should turn their face toward the sun, and for the noon prayer, they should face toward Laliş. Such prayer should be accompanied by certain gestures, including kissing the rounded neck (gerîvan) of the sacred shirt (kiras). The daily prayer services must not be performed in the presence of outsiders and are always performed in the direction of the sun. Wednesday is the holy day, but Saturday is the day of rest.[97][101]

Calendar and festivals

According to the Yezidi calendar, April 2012 marked the beginning of their year 6,762 (thereby year 1 would have been in 4,750 BC in the Gregorian calendar).[102]

The Yazidi New Year falls in Spring, on the first Wednesday of April (somewhat later than the Equinox). There is some lamentation by women in the cemeteries, to the accompaniment of the music of the Qewals, but the festival is generally characterized by joyous events: the music of dehol (drum) and zorna (shawm), communal dancing and meals, the decorating of eggs.

Similarly, the village Tawaf, a festival held in the spring in honour of the patron of the local shrine, has secular music, dance, and meals in addition to the performance of sacred music. Another important festival is the Tawûsgeran (circulation of the peacock) where Qewals and other religious dignitaries visit Yazidi villages, bringing the senjaq, sacred images of a peacock made from brass symbolizing Tawûsê Melek. These are venerated, taxes are collected from the pious, sermons are preached and holy water distributed.

The greatest festival of the year for ordinary Yazidis is the Cejna Cemaiya "Feast of the Assembly" at Laliş, the annual seven-day pilgrimage to the tomb of Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir (Şêx Adî) in Laliş, north of Mosul, Iraq.[97][103] The festival, which is celebrated from 23 Aylūl (September) to 1 Tashrīn (October), is an important time for social contact and affirmation of identity.[104]

If possible, Yazidis make at least one pilgrimage to Laliş during their lifetime, and those living in the region try to attend at least once a year for the autumn Feast of the Assembly. A sacred microcosm of the world, as it were, it contains not only many shrines dedicated to the koasasas (reincarnations of the seven holy beings in human form),[105] but a number of other landmarks corresponding to other sites or symbols of significance in other faiths, including Pirra selat "Serat Bridge" and a mountain called Mt. Arafat. The two sacred springs are called Zamzam and Kaniya Sipî "The White Spring". During the celebration, Yazidis bathe in the river, wash figures of Tawûsê Melek and light hundreds of lamps in the tombs of Şêx Adî and other saints. They sacrifice an ox, which is one reason they have been connected to Mithraism, in addition to the presence of the dog and serpent in their iconography. The sacrifice of the ox is meant to declare the arrival of fall and to ask for precipitation during winter to bring back life to the Earth in the next spring. Moreover, in astrology, the ox is the symbol of Tashrīn.

The religious centre of the event is the belief in an annual gathering of the Heptad in the holy place at this time. Rituals practised include the sacrifice of a bull at the shrine of Şêx Shams and the practice of sema.

Purity and taboos

The Yazidis' concern with religious purity and their reluctance to mix elements perceived to be incompatible is shown in not only their caste system but also various taboos affecting everyday life. The purity of Earth, Air, Fire and Water is protected by a number of taboos, e.g. against spitting on earth, water or fire. Some discourage spitting or pouring hot water on the ground because they believe that spirits or souls that may be present would be harmed or offended by such actions if they happen to be hit by the discarded liquid.

Too much contact with non-Yazidis is also considered polluting. In the past, Yazidis avoided military service which would have led them to live among Muslims and were forbidden to share such items as cups or razors with outsiders. A resemblance to the external ear may lie behind the taboo against eating head lettuce, whose name koas resembles Yazidi pronunciations of koasasa. Additionally, lettuce grown near Mosul is thought by some Yazidis to be fertilised with human waste, which may contribute to the idea that it is unsuitable for consumption. However, in a BBC interview in April 2010, a senior Yazidi authority stated that ordinary Yazidis may eat what they want, but holy men refrain from certain vegetables (including cabbage) because "they cause gases".[107]

Customs

Children are baptised at birth and circumcision is not required, but is practised by some due to regional customs.[108] Dead are buried in conical tombs immediately after death and buried with hands crossed. Yazidis are predominantly monogamous, but chiefs may be polygamous, having more than one wife.

Western perceptions

As the Yazidis hold religious beliefs that are mostly unfamiliar to outsiders, many non-Yazidi people have written about them and ascribed to their beliefs facts that have dubious historical validity. The Yazidis, perhaps because of their secrecy, also have a place in modern occultism.

In Theosophy

The Theosophical Society, in its electronic version of the Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary states:

Yezidis (Arabic) [possibly from Persian yazdan god; or the 2nd Umayyad Caliph, Yazid (r. 680–683); or Persian city Yezd] A sect dwelling principally in Iraq, Armenia, and the Caucasus, who call themselves Dasni. Their religious beliefs take on the characteristics of their surrounding peoples, inasmuch as, openly or publicly, they regard Mohammed as a prophet, and Jesus Christ as an angel in human form. Points of resemblance are found with ancient Zoroastrian and Assyrian religion. The principal feature of their worship, however, is Satan under the name of Muluk-Taus. However, it is not the Christian Satan, nor the devil in any form; their Muluk-Taus is the hundred- or thousand-eyed cosmic wisdom, pictured as a bird (the peacock).[109]

The Theosophical Society believes that Sanat Kumara is the "Lord (or Ruler) of the World".[110] Just as with Yazidi beliefs about the Peacock Angel, outsiders have, at times, viewed the Theosophical Society as worshiping Satan, due to the similarities between Sanat Kumara and the Biblical Lucifer and/or Satan.[111] Similarly, the Theosophist Mark Pinkham explicitly attempts to link the Yazidi myth of the Peacock Angel to Christ.[112] The Peacock Angel's higher self was represented by Christ, the historical Jesus being Sananda Kumara, Sanat Kumara's brother. Pinkham's claim is that Tawûsê Melek and the Theosophical Sanat Kumara are more or less the same individual and that upon the fall of the Peacock Angel, evil entered the world, causing duality to enter Tawûsê Melek's being. The Angel's fallen state was represented by his being called Satan and his outcast nature. However, Pinkham states that the Angel will eventually succeed in redeeming himself, thereby symbolically returning as Christ. The redemption of the Peacock Angel therefore serves as the redemption of the entire world and the ushering in of the eternal kingdom of God. Pinkham claims that for this reason, the Yazidis refuse to refer to Tawûsê Melek as Satan, as this would introduce time and duality into his being, and mean they must acknowledge Tawûsê Melek's eventual and predestined redemption, wherein he merges with Christ (his higher self).

The distinction between the Theosophical belief and the classic Yazidi belief, is that the office of “Lord of the World,” is merely an initiation taken by an individual soul. Every individual who takes the ninth initiation also rules the world, and will in some sense experience a fall or incarnation, a la Tawûsê Melek or Satan. The ninth initiation, in Theosophy, is the last initiation available on Earth and there is only one individual on Earth on the ninth initiation at a time.[113]

The Theosophical schema does not include the existence of higher initiations that exist above the ninth one. The only “thing” above the “Lord of the World” is the “Trinity of the Logos,” a divine and limitless entity that resides inside the sun.[114] However, the Earthly representative of the Logos, is the “Ruler of the World,” which would square with the Yazidi claim that Tawûsê Melek is an emanation of God, but not God himself. A sect of the Ahl-i Haqq, who tend to deify ‘Ali, believe that Tawûsê Melek is merely an incarnation of ‘Ali and serves as his representative on Earth.[94]:31 Furthmore, the Alawites tend to associate ‘Ali with the sun.[115][116][117]

In Western literature

_p454_GATE_OF_YEZEEDI_TEMPLE_SHEIKH_ADI.jpg)

In William Seabrook's book Adventures in Arabia, the fourth section, starting with Chapter 14, is devoted to the "Yezidees" and is titled "Among the Yezidees". He describes them as "a mysterious sect scattered throughout the Orient, strongest in North Arabia, feared and hated both by Moslem and Christian, because they are worshippers of Satan." In the three chapters of the book, he completely describes the area, including the fact that this territory, including their holiest city of Sheik-Adi, was not part of "Irak".[118]

George Gurdjieff wrote about his encounters with the Yazidis several times in his book Meetings with Remarkable Men, mentioning that they are considered to be "devil worshippers" by other ethnicities in the region. Also, in Peter Ouspensky's book "In Search of the Miraculous", he describes some strange customs that Gurdjieff observed in Yezidi boys: "He told me, among other things, that when he was a child he had often observed how Yezidi boys were unable to step out of a circle traced round them on the ground" (p. 36)

Idries Shah, writing under the pen-name Arkon Daraul, in the 1961 book Secret Societies Yesterday and Today, describes discovering a Yazidi-influenced secret society in the London suburbs called the "Order of the Peacock Angel." Shah claimed Tawûsê Melek could be understood, from the Sufi viewpoint, as an allegory of the higher powers in humanity.[119]

In H.P. Lovecraft's story "The Horror at Red Hook", some of the murderous foreigners are identified as belonging to "the Yezidi clan of devil-worshippers".[120]

In Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series novel The Letter of Marque, set during the Napoleonic wars, there is a Yazidi character named Adi. His ethnicity is referred to as "Dasni".

A fictional Yazidi character of note is the super-powered police officer King Peacock of the Top 10 series (and related comics).[121] He is portrayed as a kind, peaceful character with a broad knowledge of religion and mythology. He is depicted as conservative, ethical, and highly principled in family life. An incredibly powerful martial artist, he is able to perceive and strike at his opponent's weakest spots, a power that he claims is derived from communicating with Malek Ta'us.

The Yazidis play a significant role in the thriller Genesis Secret, by Tom Knox, which was an international best-seller in 2006, published in 23 languages. In the book, the Yazidis are portrayed as ancient guardians of the megalithic site, Gobekli Tepe, in Kurdish Turkey.

In US Army memoirs

In her memoir of her service with an intelligence unit of the US Army's 101st Airborne Division in Iraq during 2003 and 2004, Kayla Williams (2005) records being stationed in northern Iraq near the Syrian border in an area inhabited by "Yezidis". According to Williams, some Yezidis were Kurdish-speaking but did not consider themselves Kurds and expressed to her a fondness for America and Israel. She was able to learn only a little about the nature of their religion: she thought it very ancient, and concerned with angels. She describes a mountain-top Yezidi shrine as "a small rock building with objects dangling from the ceiling" and alcoves for the placement of offerings. She reported that local Muslims considered the Yezidis to be devil worshippers.

In an October 2006 article in The New Republic, Lawrence F. Kaplan echoes Williams's sentiments about the enthusiasm of the Yazidis for the American occupation of Iraq, in part because the Americans protect them from oppression by militant Muslims and the nearby Kurds. Kaplan notes that the peace and calm of Sinjar is virtually unique in Iraq: "Parents and children line the streets when U.S. patrols pass by, while Yazidi clerics pray for the welfare of U.S. forces."[122]

Tony Lagouranis comments on a Yazidi prisoner in his book Fear Up Harsh: An Army Interrogator's Dark Journey through Iraq:

There's a lot of mystery surrounding the Yazidi, and a lot of contradictory information. But I was drawn to this aspect of their beliefs: Yazidi don't have a Satan. Malak Ta'us, an archangel, God's favorite, was not thrown out of heaven the way Satan was. Instead, he descended, saw the suffering and pain of the world, and cried. His tears, thousands of years' worth, fell on the fires of hell, extinguishing them. If there is evil in the world, it does not come from a fallen angel or from the fires of hell. The evil in this world is man-made. Nevertheless, humans can, like Malak Ta'us, live in this world but still be good.[123]

Persecution of Yazidis

The belief of some followers of other monotheistic religions of the region that the Peacock Angel equates with their own unredeemed evil spirit Satan,[48]:29[36] has incited centuries of persecution of the Yazidis as "devil worshippers".[49][50]

Under the Ottoman Empire

A large Yazidi community existed in Syria, but they declined due to persecution by the Ottoman Empire.[124][125] Several punitive expeditions were organized against the Yazidis by the Ottoman governors (Wāli) of Diyarbakir, Mosul and Baghdad. The objective of these persecutions was the forced conversion of Yazidis to the Sunni Hanafi Islam of the Ottoman Empire.[126]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In post-invasion Iraq

On 7 April 2007 a crowd of up to 2,000 Yazidi stoned a 17-year-old Iraqi of the Yazidi faith Du'a Khalil Aswad to death.[127][128] Rumours that the stoning was connected to her alleged conversion to Islam prompted reprisals against Yazidis by Sunnis, including the 2007 Mosul massacre. In August 2007, some 500 Yazidis were killed in a coordinated series of bombings in Qahtaniya that became the deadliest suicide attack since the Iraq War began. In August 2009, at least 20 people were killed and 30 wounded in a double suicide bombing in northern Iraq, an Iraqi Interior Ministry official said. Two suicide bombers with explosive vests carried out the attack at a cafe in Sinjar, west of Mosul. In Sinjar, many townspeople are members of the Yazidi minority.[129]

By the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL)

In 2014, with the territorial gains of the Salafist militant group calling itself the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) there was much upheaval in the Iraqi Yazidi population. ISIL captured Sinjar in August 2014 following the withdrawal of Peshmerga troops of Masoud Barzani, forcing up to 50,000 Yazidis to flee into the nearby mountainous region.[130] In early August the town of Sinjar was nearly deserted as Kurdish Peshmerga forces were no longer able to keep ISIL forces from advancing. ISIL had previously declared the Yazidis to be devil worshippers and had taken the two nearby small oil fields and the town of Zumar as part of a plan to try to seize Mosul's hydroelectric dam.[131] Up to 200,000 people (including an estimated 40,000 Yazidi[132]) fled the city before it was captured by ISIL forces, giving rise to fears of a humanitarian tragedy.[131] Alongside the local Yazidis fleeing Sinjar were Yazidis (and Shiites) who fled to the city a month earlier when ISIL captured the town of Tal Afar.[131][52]

Most of the population fleeing Sinjar retreated by trekking up nearby mountains with the ultimate goal of reaching Dohuk in Iraqi Kurdistan (normally a five-hour drive by car). Concerns for the elderly and those of fragile health were expressed by the refugees, who told reporters of their lack of water. Reports coming from Sinjar stated that sick or elderly Yazidi who could not make the trek were being executed by ISIL. Yazidi parliamentarian Haji Ghandour told reporters that "In our history, we have suffered 72 massacres. We are worried Sinjar could be a 73rd."[131] UN groups say at least 40,000 members of the Yazidi sect, many of them women and children, had taken refuge in nine locations on Mount Sinjar, a craggy, 1,400 m (4,600 ft) high ridge identified in local legend as the final resting place of Noah's ark, facing slaughter at the hands of jihadists surrounding them below if they fled or death by dehydration if they stayed.[133] Between 20,000 and 30,000 Yazidis, most of them women and children, besieged by ISIL, escaped from the mountain after the People's Protection Units (YPG) and Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) intervened to stop ISIL and opened a humanitarian corridor for them,[134] helping them cross the Tigris into Rojava.[135] Some Yazidis minority were later escorted back to Iraqi Kurdistan by Peshmerga and YPG forces, Kurdish officials have said.[136][137]

Their plight received international media coverage,[138] which led United States President Barack Obama to authorise humanitarian airdrops of meals and water to thousands of Yazidi and Christian religious minorities trapped on Sinjar mountain. President Obama also authorised "targeted airstrikes" against Islamic militants in support of the beleaguered religious minority, and to protect American military personnel in northwest Iraq.[139][140] American humanitarian assistance began on 7 August 2014,[141] with the UK Royal Air Force subsequently contributing to the relief effort.[142] At an emergency meeting in London, Australian prime minister Tony Abbott also pledged humanitarian support,[143] while European nations resolved to join the US in helping to arm Peshmerga fighters aiding the Yazidis with more advanced weaponry.[144]

Later PKK and YPG fighters with Peshmergas and support of the US airstrikes helped the rest of the trapped Yazidis to escape from the mountain.[137][145][146] One relief worker in the evacuation operation described the conditions on Mount Sinjar as "a genocide", having witnessed hundreds of corpses.[135] Yazidi girls in Iraq allegedly raped by ISIL fighters have committed suicide by jumping to their death from Mount Sinjar, as described in a witness statement.[147] In Sinjar, ISIL destroyed a Shiite shrine and demanded that the remaining population convert to their version of Islam, pay jizya (a religious tax) or be executed.

Captured women are treated as sex slaves or spoils of war, some are driven to suicide. Women and girls who convert to Islam are sold as brides, those who refuse to convert are tortured, raped and eventually murdered. Babies born in the prison where the women are held are taken from their mothers to an unknown fate.[148][149] Nadia Murad, a Yazidi human rights activist and 2018 Nobel Peace Prize winner was kidnapped and used as a sex slave by the ISIL in 2014.[150]

Haleh Esfandiari from the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars has highlighted the abuse of local women by ISIL militants after they have captured an area. "They usually take the older women to a makeshift slave market and try to sell them. The younger girls ... are raped or married off to fighters", she said, adding, "It's based on temporary marriages, and once these fighters have had sex with these young girls, they just pass them on to other fighters."[151] Speaking of Yazidi women captured by ISIL, Nazand Begikhani said "[t]hese women have been treated like cattle... They have been subjected to physical and sexual violence, including systematic rape and sex slavery. They've been exposed in markets in Mosul and in Raqqa, Syria, carrying price tags."[152] Dr. Widad Akrawi said that ISIL uses slavery and rape as weapons of war.[153]

In September 2014, Defend International launched a worldwide campaign entitled "Save The Yazidis: The World Has To Act Now" to raise awareness about the tragedy of the Yazidis in Sinjar and to co-ordinate activities related to intensifying efforts aimed at rescuing Yazidi and Christian women and girls captured by ISIL.[154] In October 2014 the United Nations reported that more than 5,000 Yazidis had been murdered and 5,000 to 7,000 (mostly women and children) had been abducted by the ISIL.[155][156] In the same month, President of Defend International dedicated her 2014 International Pfeffer Peace Award to the Yazidis.[157][158][159][160][161][162] She asked the international community to make sure that the victims are not forgotten; they should be rescued, protected, fully assisted and compensated fairly.[154]

ISIS has, in their digital magazine Dabiq, explicitly claimed religious justification for enslaving Yazidi women.[163][164][165][166][167] According to The Wall Street Journal, ISIL appeals to apocalyptic beliefs and claims "justification by a Hadith that they interpret as portraying the revival of slavery as a precursor to the end of the world".[168] In December 2014, Amnesty International published a report.[169][170] Despite the oppression Yazidis' women have sustained, they have appeared on the news as examples of retaliation. They have received training and taken positions at the frontlines of the fighting, making up about a third of the Kurd–Yazidi coalition forces, and have distinguished themselves as soldiers.[171][172]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Allison, Christine (2004-02-20). "Yazidis i: General". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

There are probably some 200,000–300,000 Yazidis worldwide.

- ↑ "Yezidi". Adherents.com. Retrieved 2008-03-31. Cites estimates between 100,000 and 700,000.

- ↑ "Deadly Iraq sect attacks kill 200". BBC News. 2007-08-15. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ Iraq Yezidis: A Religious and Ethnic Minority Group Faces Repression and Assimilation Archived 9 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine., aina.org, 25 September 2005.

- ↑ Jakob, Christian. "Jesiden in Deutschland: Das Trauma der Vorfahren". die Tageszeitung (in German). Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ↑ Hür, Kemal. "Die Religion der Yeziden" (in German). Deutschlandradio Kultur. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Megalommatis, Muhammad Shamsaddin (28 February 2010). "Dispersion of the Yazidi Nation in Syria, Turkey, Armenia, Georgia and Europe: Call for UN Action". American Chronicle. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Yazidi in Syria Between acceptance and marginalization" (PDF). KurdWatch. kurdwatch.org. p. 4. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ↑ Andrea Glioti (18 October 2013). "Yazidis Benefit From Kurdish Gains in Northeast Syria". al-monitor. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ↑ "Приложение 2. Hациональный состав населения по субъектам Российской Федерации". Statistics of Russia (in Russian). Statistics of Russia. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "2011 Armenian census" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- 1 2 "Population by national and/or ethnic group, sex and urban/rural residence". Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Detailed tables - National regional data". Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "u:Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь" (PDF). Statistics of Belarus. p. 5. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Таблица 5.2-1 Население (городское, сельское) по национальности, полу" (PDF) (in Russian). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības (Datums=01.01.2018)" (PDF) (in Latvian). Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ↑ "4.5. Национальности или их самоназвания по самоопределению населения По республике южная осетия" (PDF) (in Russian). p. 128. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ↑ Husseini, Rana (2012). "Chapter 15. The Historical and Religious Seeds of 'Honor'". In Clark, Kelly James. Abraham's Children: Liberty and Tolerance in an Age of Religious Conflict. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18333-7. OCLC 809235956.

- ↑ "What language do the Yazidis speak?" (in Russian). Cognitive journal ШколаЖизни. 2012-06-04. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- ↑ "YAZIDIS i. GENERAL – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ "Yazidi - definition of Yazidi in English | Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ "Yazidis - BRITANNICA". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ↑ Allison, Christine (2001). The Yezidi Oral Tradition in Iraqi Kurdistan. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780700713974.

- ↑ Spät, Eszter (1985). The Yezidis. Saqi. ISBN 9780863565939.

- ↑ Russell, Jesse; Cohn, Ronald (2012). Yazidi. Book on Demand. ISBN 9785512175170.

- 1 2 3 Attewill, Fred (15 August 2007). "Background: the Yezidi". The Guardian.

- ↑ Burjus, Ahmed Khudida. "Yazidis are Ethno-Religious group, NOT Kurds".

- ↑ Asatrian, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014-09-03). The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. Routledge. ISBN 9781317544289.

- ↑ Non-State Violent Actors and Social Movement Organizations: Influence, Adaptation, and Change. Emerald Group Publishing. 2017-04-26. ISBN 9781787147287.

- ↑ Guest (2012-11-12). Survival Among The Kurds. Routledge. ISBN 9781136157363.

- ↑ Murad, Nadia; Krajeski, Jenna (2017). The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State. Tim Duggan Books. ISBN 9781524760434.

- 1 2 Eckardt, Frank; Eade, John (2011-01-01). The Ethnically Diverse City. BWV Verlag. p. 73. ISBN 978-3-8305-1641-5.

- ↑ Philip G. Kreyenbroek. "Yezidism in Europe". Retrieved 2015-12-25.

- ↑ Palmer, Michael D.; Burgess, Stanley M. (2012-03-12). The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Religion and Social Justice. John Wiley & Sons. p. 405. ISBN 978-1-4443-5536-9. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- 1 2 Darke, Diana; Leutheuser, Robert (8 August 2014). "Who, What, Why: Who are the Yazidis?". Magazine Monitor, BBC News.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Açikyildiz, Birgül (2014). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. London: I.B. Tauris & Company. ISBN 978-1-784-53216-1. OCLC 888467694.

- ↑ "Marriage and family - Yezidis". www.everyculture.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- ↑ Gidda, Mirren. "Everything You Need to Know About the Yazidis". TIME.com. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- 1 2 Gezer, Özlem (23 October 2014). "From Germany to Iraq: One Yazidi Family's War on Islamic State". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "UNHCR's Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylum-seekers". Refworld. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (April 2009). "Page 173: It further said that it had received reports that members of minority groups were allegedly forced to identify themselves as Kurdish or Arab in order to obtain access to education or health services.". UNHCR Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylum-Seekers. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

- ↑ Smith, Crispin M.I.; Shadarevian, Vartan (May 2017). "Ethno-Religious Groups". Wilting in the Kurdish Sun: The Hopes and Fears of Religious Minorities in Northern Iraq (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. pp. 20–24.

Page 20: Kurdish officials frequently put pressure on Yezidis to identify as Kurds. For some Yezidis this is an affront that they believe threatens the existence of the Yezidi people. Regardless, rights should not be attached to ethnic identity or religious affiliation.

- 1 2

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, by Barbara A. West, Infobase Publishing, January 1, 2009 – "... the ancient Yezidi religion (monotheist with elements of nature worship) ..." p. 53

- ↑ Religious Freedom in the World, by Paul A. Marshall, Rowman & Littlefield, 2000 – "The Ezidi ('Yezidi') religion, a monotheistic faith ..." p. 212

- ↑ Empson, R.H.W. (1928). The Cult of the Peacock Angel. London: H.F. & G. Witherby. p. 184.

In connection with the Yezidi beliefs in Shaitan, Melak Ta'us and Hell, there is a consideration which may be of great important in the inquiry into the memories conveyed in the term Melak Ta'us. In modern Yezidi belief there is no Hell, as it was extinguished by the weeping of a diseased child, who cried into a yellow (asfar) jar for seven years, and this was emptied over the fire of Hell and extinguished them. This child is variously named Abrik Shautha and Ibrik al-Asfar (the Yellow). A variant of the legend says it was the weeping of Shaitan during his seven thousand years of exile in Hell that extinguished the fires. With reference to these legends it has been suggested that Melak Ta'us is a memory of Ta'uz, said to be a form of the very ancient Babylonian hero-god Tammuz, and it is to be remembered that weeping for the terrible legendary sufferings in the seven forms of death to which he was subjected is a prominent feature in the ceremonies once celebrated in connection with Tammuz.

- ↑ Asatrian and Arakelova 2014, 26–29

- 1 2 3 van Bruinessen, Martin (1992). "Chapter 2: Kurdish society, ethnicity, nationalism and refugee problems". In Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan. The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 26–52. ISBN 978-0-415-07265-6. OCLC 919303390.

The Peacock Angel (Malak Tawus) whom they worship may be identified with Satan, but is to them not the lord of Evil as he is to Muslims and Christians

- 1 2 Li, Shirley (8 August 2014). "A Very Brief History of the Yazidi and What They're Up Against in Iraq". The Atlantic.

- 1 2 Jalabi, Raya (11 August 2014). "Who are the Yazidis and why is Isis hunting them?". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Thomas, Sean (19 August 2007). "The Devil worshippers of Iraq". The Daily Telegraph.

- 1 2 "Who Are the Yazidi, and Why Is ISIS Targeting Them?". NBC News. 8 August 2014.

- ↑ "Question of the Frontier Between Turkey and Iraq" (PDF). Geneva: League of Nations. 20 August 1925. p. 49.

they are ... are almost the only settled population in the Western desert.

- ↑ "On Vulnerable Ground". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ Ghanim, David (2011-09-30). Iraq's Dysfunctional Democracy. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39801-8.

- ↑ Ghanim, David. Iraq's Dysfunctional Democracy. p. 34.

- ↑ "لقاء الامير تحسين بك على قناة العربية" (Video). Al Arabiya. 17 October 2014.

- ↑ Foltz, Richard (2013). Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present. London, England: Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-780-74307-3. OCLC 839388544.

- 1 2 Yazidis i. General, iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ Brennan, Shane; Herzog, Marc. "Turkey and the Politics of National Identity: Social, Economic and Cultural Transformation". New York: I.B.Tauris, 2014. ISBN 978-1-78076-539-6.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "UNHCR's Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylum-seekers". Refworld: 76–82. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ "YAZIDIS". 20 December 2015.

- ↑ Federal Research Division. Syria. "Chapter 5: Religious Life". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ Commins, David Dean (2004). Historical Dictionary of Syria. Scarecrow Press. p. 282. ISBN 0-8108-4934-8. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Yazidi temple, third in the world, opened in Tbilisi". DFWatch. 2015-06-19. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ↑ "2011 Armenian census" (PDF). National Statistical Service. 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "De Jure Population (Urban, Rural) by Age and Ethnicity" (PDF). National Statistical Service. 2001. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ↑ https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yazidis_in_Armenia

- ↑ http://armenianweekly.com/2014/08/27/confronting-yezidid-genocide/

- ↑ Sherwood, Harriet (2016-07-25). "World's largest Yazidi temple under construction in Armenia". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ "The Role of the Father – Honor Killing Verdict Has Prosecutors Wanting More (English)". Der Spiegel. 2012-05-24. Retrieved 2012-05-27.

- ↑ Betts, Robert Brenton (2013). The Sunni-Shi'a Divide: Islam's Internal Divisions and Their Global Consequences.

- ↑ "UNHCR's Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Needs of Iraqi Asylum-Seekers" (PDF). p. 11.

- ↑ Stafford, R.S. The Tragedy of the Assyrians. p. 15.

- ↑ Smith, Andrew Phillip. The Gnostics: History * Tradition * Scriptures * Influence.

- ↑ Concise encyclopedia of the Middle East. 1973. p. 325.

- ↑ Dalyan, Dogan, Murat Gokhan, Cabir. "An Overview of 19th Century Yezidi Women" (Who Are the Yezidis?): 114.

- ↑ A History of the Arab Peoples: Updated Edition. 2013.

- ↑ O'Leary, Carole A. "The Kurds of Iraq: Recent History, Future Prospects" (PDF). Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Armenia Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments.

- ↑ Levinson, David (1998). Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook. p. 203.

- ↑ Serinci, Deniz (28 May 2014). "The Yezidis of Armenia Face Identity Crisis over Kurdish Ethnicity". Rudaw Media Network.

- ↑ Green, Emma (13 August 2014). "The Yazidis, a People Who Fled". The Atlantic.

Recently, Yazidis in Armenia tried to establish themselves as an independent, non-Kurdish ethnic group for political reasons...

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | UNHCR's Eligibility Guidelines for Assessing the International Protection Needs of Iraqi Asylum-seekers". Refworld. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- 1 2 3 4 "Encyclopaedia Iranica: Yazidis". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ↑ P.G. Kreyenbroek, "Yazīdī" in Encyclopedia of Islam, s.v.

- ↑ Late Antique Motifs in Yezidi Oral Tradition by Eszter Spät. Ch. 9 "The Origin Myth of the Yezidis" section "The Myth of Shehid Bin Jer" (p. 347)

- ↑ Joseph 1919, pp. 119–21

- ↑ "Consequently, despite corresponding to isolated and homogenous populations, contemporary Syriacs and Yazidis from Northern Iraq may in fact have a stronger continuity with the original genetic stock of the Mesopotamian people, which possibly provided the basis for the ethnogenesis of various subsequent Near Eastern populations.

the Northern Iraqi Syriac and Yazidi populations from the current study were found to position in the middle of a genetic continuum between the Near East and Southeastern Europe." http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0187408 - ↑ https://www.academia.edu/10772192/The_Cults_of_the_Angels_The_Indigenous_Religions_of_Kurdistan

- ↑ Asher-Schapiro, Avi (11 August 2014). "Who Are the Yazidis, the Ancient, Persecuted Religious Minority Struggling to Survive in Iraq?". National Geographic.

- 1 2 3 4 Kjeilen, Tore. "Yazidism". Encyclopaedia. LookLex. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

Malak Taus filled 7 jars of tears through 7,000 years. His tears were used to extinguish the fire in hell. Therefore, there is no hell in Yazidism.

- 1 2 Allison C 1998 The Evolution of Yazidi Religion From Spoken Word to Written Scripture. ISIM Newsletter. https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/bitstream/handle/1887/16757/ISIM_1_The_Evolution_of_the_Yezidi_Religion_From_Spoken_Word_to_Written_Scripture.pdf?sequence=1

- 1 2 3 4 Asatryan, Garnik S.; Arakelova, Victoria (2014). The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and Their Spirit World. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-1-317-54429-6. OCLC 890090566.

p. 3: A careful analysis of the Yezidi triad will show its component deities to be unambiguous manifestations of the one god worshipped by adherents. … The Yezidi triad comprises the following: Malak-Tawus, the Peacock-Angel (in the Yezidi imagination being featured as a bird, a peacock or a cock, and sometimes even a dove); Sheikh ‘Adi (Seyx ‘Adi = Sheikh ‘Adi bin Musafir, a historical personality, the founder of the proto-Yezidi community, as an old man); and Sultan Yezid (Silt’an Ezid, as a youth). All three characters are manifestations of god – xwade (or xwadi, xuda, the term deriving from the New Pers. xuday). pp. 21-22: A little star fell from heaven, said an ancient Yezidi legend, and hid in the depth of the then still dark earth. … That beam, that particle of endless light, was the great and glorious Melak-Tauz [sic!]; … he believed and hoped that a spark of the better light that had been brought by him would not be extinguished even among cruel and corrupt people, and the bright hope did not deceive Melak-Tauz. There came about kind people, pure in heart, who had preserved the unextinguished spark of endless light falling on earth as a bright start of heaven; they recognized and welcomed Melak-Tauz, … Those people were the Yezidis; until now they go after Melak-Tauz, hated and cursed by the whole world. p. 31: Malak-Tawusis believe that ‘Ali had existed before the Creation as Perfect (Absolute) Light (nur-e mutlaq). Four servitor Angels were created from ‘Ali's pure essence … Israil from his tongue, and Malak-Amin (i.e. Malak-Tawus) as the reincarnation of ‘Ali (dun-e ‘Ali). p. 33: This verse is interesting because it features the concept of the Yezidis having originated from Adam directly, rather from his union with Eve, as is the case with all the rest of mankind.

- ↑ "The Cult of Angels". Kurdistanica. July 17, 2008.

The Cult believes in a boundless, all encompassing, yet fully detached "Universal Spirit" (Haq), whose only involvement in the material world has been his primeval manifestation as a supreme avatar who after coming into being himself, created the material universe. (Haq, incidentally, is not derived from the Arabic homophone haqq, meaning "truth," as commonly and erroneously believed.) The Spirit has stayed out of the affairs of the material world except to contain and bind it together within his essence. The prime avatar who became the Creator is identified as the Lord God in all branches of the Cult except Yezidism, as discussed below.

- ↑ "Yezidi Reformer: Sheikh Adi". The Truth about the Yezidis. YezidiTruth.org, A Humanitarian Organization, Sedona, Arizona. Archived from the original on 20 March 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Yezidi Religious Tradition". YezidiTruth.org.

- ↑ Allison, Christine (2001). The Yazidi Oral Tradition in Iraq. Psychology Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-7007-1397-2. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Assyrian International Newsagency (AINA), ''Iraqi Yazidi MP: We Are Being Butchered Under the Banner of 'There is No God But Allah'". AINA. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ↑ Salih, "Islamic Extremists Pose New Risks for Religious Minorities in Iraq", New York Times, 24 June 2014.

- ↑ MacFarquhar, Neill (2003-01-03). "Bashiqa Journal: A Sect Shuns Lettuce and Gives the Devil His Due". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

Yazidis pray three times a day, at dawn, midday and sunset, facing the direction of the sun each time. 'The sun is very holy to us,' said Walid Abu Khudur, the stocky, bearded guardian of the temple built in honor of a holy man here. 'It is like the eye of God, so we pray toward it.'... They have adopted Christian rituals like baptism and a smattering of practices from Islam ranging from circumcision to removal of their shoes inside their temples. The importance of fire as a divine manifestation comes from Zoroastrianism, the ancient Iranian faith that forms the core of Yazidi beliefs. Indeed their very name is likely taken from an old Persian word for angel.

- ↑ Yazidis celebrate New Year in Iraq, Al Jazeera (YouTube), 28 April 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Hedges, Chris (31 May 1993). "Sheik Adi Journal; Satan's Alive and Well, but the Sect May Be Dying". The New York Times.

The Yazidis, who are part of Iraq's Yazidi minority, had 100 of 150 villages demolished during the counterinsurgency operation against the Kurdish rebel movement that reached its peak in 1988. The campaign, which moved hundreds of thousands of people to collective villages, saw 4,000 Yazidi villages dynamited into rubble. ... The sect follows the teachings of Sheik Adi, a holy man who died in 1162, and whose crypt lies in the shrine in the Lalish Valley, about 15 miles [24 km] east of Mosul. The shrine's graceful, fluted spires poke above the trees and dominate the fertile valley. ... Like Zoroastrians they venerate fire, the sun and the mulberry tree. They believe in the transmigration of souls, often into animals. The sect does not accept converts and banishes anyone who marries outside the faith. Yazidis are forbidden to disclose most of their rituals and beliefs to nonbelievers.

- ↑ Allison, Christine. YAZIDIS. Encyclopædia Iranica (1996). New York. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ↑ http://www.yezidisinternational.org/abouttheyezidipeople/religion/. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ Lair, Patrick (19 January 2008). "Conversation with a Yazidi Kurd". eKurd Daily. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ "Richness of Iraq's minority religions revealed", BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Page 363 https://archive.org/stream/sixmonthsinasyr00parrgoog/sixmonthsinasyr00parrgoog_djvu.txt

- ↑ "Yezidis". Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary. Theosophical University Press. 1999.

- ↑ Leadbeater, C.W. The Masters and the Path. Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1925 (Reprint: Kessinger Publishing, 1997) Pages 296–299

- ↑ "The Eternal Youth: Thoughts on Sanat Kumara". Aleph's Heretical Domain. April 21, 2014.

Some people, mostly Christians, equate Sanat Kumara with Lucifer/Satan, perhaps due to the fact that in Theosophical lore, Sanat Kumara arrived to Earth from Venus, just as Lucifer was associated with the morning star (Venus), as well as Sanat Kumara being referred to as King of the World or Lord of the World.

- ↑ Pinkham, Mark Amaru (2002). The Truth Behind the Christ Myth: The Redemption of the Peacock Angel. Adventures Unlimited Press.

- ↑ Leadbeater, C.W. (2007). The Masters and the Path. Cosimo, Inc.

- ↑ Blavatsky, H. P. (1968 [1889]). The Key to Theosophy. London: Theosophical Publishing House.

- ↑ Procházka, Stephan (September 2015). "The Alawis". Oxford Research Encyclopedias.

The deity is comparable to the sun in that He radiates light and heat forever.

- ↑ Christensen-Ernst, Jørgen (2012). Antioch on the Orontes. Hamilton Books. p. 146.

They expect to regain their former status, making themselves deserving this by living as good Nusayris during consecutive rebirths, eventually ending up as stars or perfect souls in heaven. Ali himself is the sun.

- ↑ Lyde, Samuel (1860). The Asian Mystery. p. 138.

From this reverence for light, since the sun is the light of lights, Ali is supposed to reside in the sun and in the eyes of the sun, from which he is said to appear; and when they pray, according to the Ansairee catechism, they turn their faces toward the sun.

- ↑ Seabrook, W.B., Adventures in Arabia, Harcourt, Brace, and Company (1927).

- ↑ Shah, Idries (1964). The Sufis. Anchor Doubleday. pp. 437–38. ISBN 0-385-07966-4.

- ↑ Lovecraft, H.P., The Complete Fiction, Barnes & Noble, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4351-2296-3

- ↑ Moore, Alan and Ha, Gene (1999–2000) Top Ten issues 1–12,

- ↑ Kaplan, Lawrence F. (2007-10-31). "Sinjar Diarist: Devil's Advocates". The New Republic. 235 (4790): 34.

- ↑ Lagouranis, Tony (2007). Fear Up Harsh: An Army Interrogator's Dark Journey through Iraq. New American Library. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-451-22112-4.

- ↑ Commins, David Dean. Historical Dictionary of Syria. Scarecrow Press. p. 282. ISBN 0-8108-4934-8.

- ↑ Ghareeb, Edmund A. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Iraq. Scarecrow Press. p. 248. ISBN 0-8108-4330-7.

- ↑ Hastings, James (2003). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 18. Kessinger. p. 769. ISBN 0-7661-3695-7.

- ↑ "Video Captures Stoning of Kurdish Teenage Girl". 2007-04-25.

- ↑ Lattimer, Mark (13 December 2007). "Freedom lost". The Guardian.

- ↑ "At least 20 killed in Iraq blast". CNN.com International. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ↑ "Isil militants execute dozens from Yazidi minority". Gulf News. 2014-08-05. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- 1 2 3 4 Morris, Loveday (3 August 2014). "Families flee as Islamic State extremists seize another Iraqi town, pushing back the Kurds". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Bram Janssen & Sameer N. Yacoub (4 August 2014). "Iraq Air Force to Back Kurds Fighting Islamists". Associated Press. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Chulov, Martin (6 August 2014). "40,000 Iraqis stranded on mountain as Isis jihadists threaten death". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Kurds rescue Yazidis from Iraqi mountain". Al Jazeera. 10 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- 1 2 "Thousands of Yazidis 'still trapped' on Iraq mountain". BBC News. 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Siddique, Haroon (10 August 2014). "20,000 Iraqis besieged by ISIL escape from mountain after US air strikes". The Guardian.

- 1 2 Hadid, Diaa; Mroue, Bassem (12 August 2014). "Syrian Kurdish Fighters Rescue Stranded Yazidis". Associated Press.

In a dusty camp here, Iraqi refugees have new heroes: Syrian Kurdish fighters who battled militants to carve out an escape route for tens of thousands trapped on a mountaintop. While the U.S. and Iraqi militaries struggle to aid the starving members of Iraq's Yazidi minority with supply drops from the air, the Syrian Kurds took it on themselves to rescue them. The move underlined how they—like Iraqi Kurds—are using the region's conflicts to establish their own rule. For the past few days, fighters have been rescuing Yazidis from the mountain, transporting them into Syrian territory to give them first aid, food and water, and returning some to Iraq via a pontoon bridge. [...] The U.N. estimated around 50,000 Yazidis fled to the mountain. But by Sunday, Kurdish officials said at least 45,000 had crossed through the safe passage, leaving thousands more behind and suggesting the number of stranded was higher.

- ↑ "Iraqi Yazidis: 'If we move they will kill us'". Al Jazeera. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Obama, Barack (7 August 2014). "Statement by the President". Whitehouse.gov.

- ↑ Cooper, Helene; Landler, Mark; Rubin, Alissa J. (7 August 2014). "Obama Allows Limited Airstrikes on ISIS". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Obama authorises Iraq air strikes on Islamist fighters". BBC World News. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "Britain's RAF makes second aid drop to Mount Sinjar Iraqis trapped by Isis – video". The Guardian. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "Iraq crisis: Tony Abbott says Australia's role in Iraq only humanitarian 'at this stage'; UN calls for 'urgent' international action". ABC News. 13 August 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ "Europe pledges aid, equipment to Iraq". ABC News. 12 August 2014. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ "A U.S.-designated terrorist group is saving Yazidis and battling the Islamic State". Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ↑ "The Drama of Sinjar: Escaping the Islamic State in Iraq". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ↑ Ahmed, Havidar (14 August 2014). "The Yezidi Exodus, Girls Raped by ISIS Jump to their Death on Mount Shingal". Rudaw Media Network. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Islamic State crisis: Yazidi anger at Iraq's forgotten people". BBC News. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "IS in Iraq: Yazidi women raped, murdered and sold as brides - Christian News on Christian Today". Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Alter, Charlotte (20 Dec 2015). "A Yezidi Woman Who Escaped ISIS Slavery Tells Her Story". Time Magazine. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ Brekke, Kira (8 September 2014). "ISIS Is Attacking Women, And Nobody Is Talking About It". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ Ivan Watson, "'Treated like cattle': Yazidi women sold, raped, enslaved by ISIS", CNN, 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "Dr Widad Akrawi Interviewed at RojNews: How should the international community classify the systematic massacre of the Yezidi civilians in Sinjar by IS jihadists that included taking Yezidi girls as sex slaves". Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- 1 2 "Save The Yazidis: The World Has To Act Now". Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ↑ Steve Hopkins, "Full horror of the Yazidis who didn't escape Mount Sinjar: UN confirms 5,000 men were executed and 7,000 women are now kept as sex slaves," Daily Mail, 14 October 2014

- ↑ Richard Spencer, "Isil carried out massacres and mass sexual enslavement of Yazidis, UN confirms", The Daily Telegraph, 14 October 2014.

- ↑ "Dr Widad Akrawi awarded International Pfeffer Peace Prize". Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Dr Akrawi Dedicated Peace Award to Yezidis, Christians and Kobane". Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Dr. Widad Akrawi Barış ödülünü Kobanê ve Şengal'e adadı" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Peace award dedicated to Kobanî and Şengal". Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Dr. Widad Akrawi Xelata Aştiyê pêşkêşî Kobanê û Şengalê hat kirin" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Xelata Aştiyê diyarî Kobanê hat kirin" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ Reuters, "Islamic State Seeks to Justify Enslaving Yazidi Women and Girls in Iraq", Newsweek, 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Athena Yenko, "Judgment Day Justifies Sex Slavery Of Women – ISIS Out With Its 4th Edition Of Dabiq Magazine," International Business Times-Australia, 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Allen McDuffee, "ISIS Is Now Bragging About Enslaving Women and Children," The Atlantic, 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Salma Abdelaziz, "ISIS states its justification for the enslavement of women", CNN, 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Richard Spencer, "Thousands of Yazidi women sold as sex slaves 'for theological reasons', says ISIS", The Daily Telegraph, 13 October 2014.

- ↑ Nour Malas, "Ancient Prophecies Motivate Islamic State Militants: Battlefield Strategies Driven by 1,400-year-old Apocalyptic Ideas", The Wall Street Journal, 18 November 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ↑ "Islamic State: Yazidi women tell of sex-slavery trauma". BBC News. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sex slavery 'pushes ISIL victims to suicide'", Al Jazeera, 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Dirik, Dilar (August 21, 2015). "From Genocide to Resistance: Yazidi Women Fight Back". Newsgroup: www.teleSURtv.net/english. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ↑ Barbarani, Sofia (September 2, 2014). "'Islamic State tore our families apart. Now we're fighting back'. Meet the Kurdish women's resistance army". Newsgroup: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

Further reading

- Açıkyıldız, Birgül (2014). The Yezidis: The History of a Community, Culture and Religion. London: I.B. Tauris & Company. ISBN 978-1-784-53216-1. OCLC 888467694.

- Cumont, Franz (1911). The Oriental Religions in Roman Paganism. Chicago, IL: Open Court Publishing. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-0-486-20321-8. OCLC 670375427.

- Drower, E.S. (1941). Peacock Angel; Being Some Account of Votaries of a Secret Cult and Their Sanctuaries. London: John Murray. OCLC 4821609.

- Haji, Salman H., Pharmacist, Lincoln NE US

- Husseini, Rana (2012). "Chapter 15. The Historical and Religious Seeds of 'Honor'". In Clark, Kelly James. Abraham's Children: Liberty and Tolerance in an Age of Religious Conflict. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18333-7. OCLC 809235956.

- Joseph, Isya (January 1909). "Yezidi Texts". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 25 (2): 111–156. doi:10.1086/369616. JSTOR 527914.

- Omarkhali, Khanna; Xankî, Kovan (2009). Metodeka analîza qewlên Êzdiyan: li ser mesela qewlê Omer Xala û Hesen Çinêrî=A Method of the Analysis of the Yezidi Qewls: On the example of the Religious Hymn of Omar Khala and Hesin Chineri (in Kurdish). Beyoğlu, İstanbul: Avesta Basın Yayın. ISBN 978-9-944-38293-9. OCLC 703443917.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. (1995). "Yezidism -- Its Background, Observances, and Textual Tradition". Texts and Studies in Religion (in Kurdish with English translations). Lewiston, Queenston and Lampeter, NY: Edwin Mellen Press. 62. OCLC 31377794. ISBN 978-0-773-49004-8

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Kartal, Z.; Omarkhali, Kh.; Rashow, Kh. Jindy (2009). Yezidism in Europe: Different Generations Speak About Their Religion. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-06060-8. OCLC 554952854.

- Kurdoev, K.K. "Ob alfavite ezidskikh religioznykh knig" (Report on the alphabet of the Yezidi religious books). Pis'mennye pamiatniki i problemy istorii kul'tury narodov Vostoka. VIII godichnaia nauchnaia sessiia LO IV AN SSSR. Leningrad, 1972, pp. 196–199. In Russian.

- Kurdoev, K.K. "Ob avtorstve i iazyke religioznykh knig kurdov XI–XII vv. predvaritel'noe soobshchenie" (Preliminary report on the Yezidi religious books of the eleventh-twelfth centuries: their author and language). VII godichnaia nauchnaia sessiia LO IV AN SSSR. Leningrad, 1971, pp. 22–24. In Russian.

- Marie, A. 1911. "La découverte récente des deux livres sacrés des Yêzîdis". Anthropos, 1911/VI, 1. pp. 1–39.

- Menzel, Th. "Yazidi, Yazidiya" in Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- Omarkhali, Kh. "Yezidizm. Iz glubini tisyachaletiy" (Yezidism. From the early millennia). Sankt Peterburg, 2005. In Russian.

- Omarkhali, Kh. "Yezidism: Society, Symbol, Observance". Istanbul, 2007. In Kurdish.

- Reshid, T. Yezidism: historical roots, International Journal of Yezidi Studies, January 2005.

- Reshid, R., Etnokonfessionalnaya situasiya v sovremennom Kurdistane. Moskva-Sankt-Peterburg: Nauka, 2004, p. 16. In Russian.

- Rodziewicz, A., Yezidi Eros. Love as The Cosmogonic Factor and Distinctive Feature of The Yezidi Theology in The Light of Some Ancient Cosmogonies, Fritillaria Kurdica, 2014/3,41, pp. 42–105.

- Rodziewicz, A., Tawus Protogonos: Parallels between the Yezidi Theology and Some Ancient Greek Cosmogonies, Iran and the Caucasus, 2014/18,1, pp. 27–45.

- Wahbi, T., Dînî Caranî Kurd, Gelawej Journal, N 11–12, Baghdad, 1940, pp. 51–52. In Kurdish.

- Williams, Kayla, and Michael E. Staub. 2005. Love My Rifle More Than You. W.W. Norton, New York. ISBN 0-393-06098-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yazidism. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Les Ezidis de France

- Yazda – A Global Yazidi Organization

- Yezidi Web (via the Wayback Machine)

- "Being Yezidi", on Yezidi identity politics in Armenia, by Onnik Krikorian, first published by Transitions Online (2004).

- The Beginning of the Universe, photos and a description of Yezidi life in Lalish, Iraq, by Michael J. Totten (22 February 2006).

- "Armenia: Yezidi Identity Battle" by Onnik Krikorian, in Yerevan, Institute for War & Peace Reporting (2 November 2006).

- Rubin, Alissa J. (2007-10-14). "Persecuted Sect in Iraq Avoids Its Shrine". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-08-04.