Religion in Russia

Religion in Russia (2012)[1]

Religion in Russia is diverse with Christianity, especially Orthodoxy, being the most widely professed faith, but with significant minorities of Irreligious people, Muslims and Pagans . A 1997 law on religion recognises the right to freedom of conscience and creed to all the citizenry, the spiritual contribution of Orthodox Christianity to the history of Russia, and respect to "Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Judaism and other religions and creeds which constitute an inseparable part of the historical heritage of Russia's peoples",[3] including ethnic religions or Paganism, either preserved or revived.[4] According to the law, any religious organisation may be recognised as "traditional" if it was already in existence before 1982, and each newly founded religious group has to provide its credentials and re-register yearly for fifteen years, and, in the meantime until eventual recognition, stay without rights.[3]

The Russian Orthodox Church, though its influence is thin in Siberia and southern Russia, where there has been a "remarkable revival of pre-Christian religion",[5] acts as the de facto if not de jure privileged religion of the state, claiming the right to decide which other religions or denominations are to be granted the right of registration.[3] Some Protestant churches which were already in existence before the Russian Revolution have been unable to re-register, and the Catholic Church has been forbidden to develop its own territorial jurisdictions.[6] According to some Western observers, respect for freedom of religion by Russian authorities has declined since the late 1990s and early 2000s.[7][8] Activities of the Jehovah's Witnesses are currently banned in Russia.

Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 there has been a revival and spread of Siberian shamanism,[9] and the emergence of Hindu[10] and new religious movements throughout Russia. There has been an "exponential increase in new religious groups and alternative spiritualities", Eastern religions and Neopaganism, even among self-defined "Christians"—a term which has become a loose descriptor for a variety of eclectic views and practices.[11] Russia has been defined by the scholar Eliot Borenstein as the "Southern California of Europe" because of such a blossoming of new religious movements, and the latter are perceived by the Russian Orthodox Church as competitors in a "war for souls".[11]

History

Before the tenth century, Russians practised Slavic religion. As recalled by the Primary Chronicle, Orthodox Christianity was made the state religion of Kievan Rus' in 987 by Vladimir the Great, who opted for it among other possible choices as it was the religion of the Byzantine Empire. Since then, religion, mysticism and statehood remained intertwined elments in Russia's identity.[12] The Russian Orthodox Church, perceived as the glue consolidating the nation, accompanied the expansion of the Russian Empire in the eighteenth century. Czar Nicholas I's ideology, under which the empire reached its widest extent, proclaimed "Orthodoxy, autocracy and nation" (Pravoslavie, samoderzhavie, narodnost') as its foundations. The dominance of the Russian Orthodox Church was sealed by law, and, as the empire incorporated peoples of alternative creeds, religions were tied to ethnicities to skirt any issue of integration. Until 1905, only the Russian Orthodox Church could engage in missionary activity to convert non-Orthodox people, and apostasy was treated as an offense punishable by law. Catholicism, Islam and other religions were tolerated only among outsider (inoroditsy) peoples but forbidden from spreading among Russians.[13]

Throughout the history of early and imperial Russia there were, however, religious movements which posed a challenge to the monopoly of the Russian Orthodox Church and put forward stances of freedom of conscience, namely the Old Believers—who separated from the Russian Orthodox Church after Patriarch Nikon's reform in 1653 (the Raskol)—, and Spiritual Christianity (or Molokanism).[14] It is worth noting that the Russian Orthodox Church itself never forbade personal religious experience and speculative mysticism, and Gnostic elements had become embedded in Orthodox Christianity since the sixth century, and later strengthened by the popularity of Jakob Böhme's thought in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Orthodox seminaries.[15]

By the end of the eighteenth century, dvoeverie ("double faith"), popular religion which preserved Slavic pantheism under a Christianised surface, found appreciation among intellectuals who tried to delineate Russian distinctiveness against the West.[15] At the dawn of the twentieth century, esoteric and occult philosophies and movements, including Spiritualism, Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Hermeticism, Russian cosmism and others, became widespread.[16] At the same time the empire had begun to make steps towards the recognition of the multiplicity of religions that it had come to encompass, but they came to an abrupt end with the Russian Revolution in 1917.[17] After the revolution, the Russian Orthodox Church lost its privileges, as did all minority religions, and the new state verged towards an atheist official ideology.[17] Under the Soviet Union, the Russian Orthodox Church lived periods of repression and periods of support and cooptation by the state.[18] Despite the policies of state atheism, censuses reported a high religiosity among the population; in 1929, 80% of the population were believers, and in 1937 two-thirds described themselves as believers, of whom three-fourths as Orthodox Christians.[19] The Russian Orthodox Church was supported under Joseph Stalin in the 1940s, after the Second World War, then heavily suppressed under Nikita Khrushchev in the 1960s, and then revived again by the 1980s.[18] While it was legally reconstituted only in 1949,[20] throughout the Soviet period the church functioned as an arm of the KGB; many hierarchs of the post-Soviet church were former KGB agents, as demonstrated by the opening of KGB archives in the 1990s.[21]

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1987–1991, the Russian Orthodox Church has struggled to regain its erstwhile monopoly of religious life, despite it and other Christian churches which existed since before the Revolution have found themselves in a radically transformed context characterised by a religious pluralism unknown before 1917.[17] During the Soviet period, religious barriers were shattered, as religions were no longer tied to ethnicity and family tradition, and an extensive displacement of peoples took place. This, together with the more recent swift ongoing development of communications, has resulted in an unprecedented mingling of different religious cultures.[17]

_2.jpg) Saint George and the Dragon, 16th-century icon from Pskov.

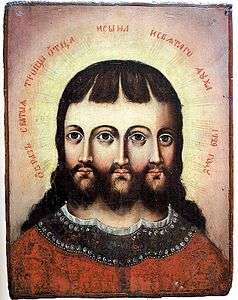

Saint George and the Dragon, 16th-century icon from Pskov. The Trinity (1729), icon by an unknown artist from Tobolsk.

The Trinity (1729), icon by an unknown artist from Tobolsk.

.jpg) Group of Molokans, 1870s.

Group of Molokans, 1870s. Circle of young atheists at a school in Murom, 1930s.

Circle of young atheists at a school in Murom, 1930s.

Study approaches

In the study of religions in Russia, the "ethnic principle" is based on the assumption that the entire number of people belonging to a given ethnic group are adherents of that group's traditional religion. This principle is often used to estimate the magnitude of very small groups, for instance Finnish Lutheranism at 63,000, assuming that all the 34,000 Finns and 28,000 Estonians of Russia are believers in their historical religion; or German Lutheranism at 400,000, assuming that all Germans in Russia believe in their historical religion. However, whether for small or larger groups, this approach may lead to gross mistakes.[22]

The ethnic principle is sometimes misused to deliberately inflate the prevalence of certain religions, especially the larger ones, for political aims. For instance, Islamic and Orthodox leaders routinely claim that their religions have respectively 20 million and 120 million adherents in Russia, by counting all the individuals belonging to the ethnic groups which historically belonged to these religions.[22] By applying the ethnic principle, people who are indifferent to religion or are outspokenly atheists, those who have converted to a different faith to that assigned by nationality, and people who participate in religions which historically have not been associated to specific ethnic groups in Russia—namely Old Believers, new Russian converts to Protestantism, Catholicism and Eastern religions, and others—are automatically excluded from the calculations.[22]

Another criterion to count religious populations in Russia is that of "religious observance". Based on this principle, very few Russians would be religious. It has been found that between 0.5% and 2% of people in big cities attend Easter services, and overall just between 2% and 10% of the total population (3 to 15 million people) are actively practising Orthodox Christians. The proportion of practising Muslims among ethnic groups which are historically Islamic is larger, 10% to 40% depending on the group, and yet smaller than any assumption based on the ethnic principle.[23]

The most accurate criterion to count religious populations in Russia is that of "self-identification", which allows to count also those people who identify themselves with a given religion but do not actually practise it. This principle provides a picture of how much given ideas and outlooks are widespread among the people.[24] Nevertheless, it has been noted that different people often give different meanings to the same identity markers; for instance, large percentages of people who self-identify as "Orthodox" have been found to believe that God is a "life force", to believe in reincarnation, astral connections, and other New Age ideas.[25]

Another method that has sometimes been used to determine the magnitude of religions in Russia is to count the number of their officially registered organisations. Such criterion, however, leads to inaccurate assumptions for various reasons. There is not the same arithmetic relationship between religions' number of local organisations and the number of their believers, as different religions have different organisational structures. Furthermore, different religions have different attitudes towards the registration of their organisations, and secular authorities register some without difficulties while hinder the registration of others. For instance, the Russian Orthodox Church is eager to register its communities when they are still at the embryonal stage, and many of them are actually inactive; the Old Believers traditionally do not consider registration as essential, and some branches reject it in principle; and Protestant churches have the largest number of unregistered congregations, probably around ten thousand, most of them extremely small groups, and while many denominations discourage registration, they often also face a negative disposition from secular authorities.[26]

Demographics

In August 2012 the first large-scale survey and mapping of religions in Russia based on self-identification was published in the Arena Atlas, an extension of the 2010 Census, with data on seventy-nine out of eighty-three of the federal subjects of Russia.[1][2] On a rounded total population of 142,800,000 the survey found that 66,840,000 people, or 47.1% of the total population, were Christians.[1] Among them, 58,800,000 or 41% of the population were believers in the Russian Orthodox Church, 5,900,000 or 4.1% were Christians without any denomination, 2,100,000 or 1.5% were believers in Orthodox Christianity without belonging to any church or (a smaller minority) belonging to non-Russian Orthodox churches (including Armenian and Georgian), 400,000 or 0.2% were Orthodox Old Believers, 300,000 or 0.2% were Protestants, and 140,000 (less than 0.1%) were Catholics.[1] Among the non-Christians, 9,400,000 or 6.5% of the population were Muslims (including Sunni Islam, Shia Islam, and a majority of unaffiliated Muslims), 1,700,000 or 1.2% were Pagans (including Rodnovery, Uatsdin, and other religions) or Tengrists (Turco-Mongol shamanic religions and new religions), 700,000 or 0.5% were Buddhists (mostly of the Tibetan schools), 140,000 or 0.1% were Hindus (including Krishnaites), and 140,000 were religious Jews.[1] Among the not religious population, 36,000,000 people or 25% declared to "believe in God (or in a higher power)" but to "not profess any particular religion", 18,600,000 or 13% were atheists, and 7,900,000 or 5.5% did not state any religious, spiritual or atheist belief.[1]

Chronological statistics

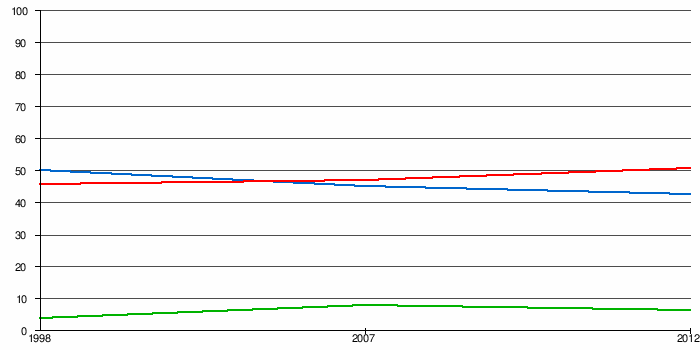

| Religion | 1998[27] | 2007[28] | 2012[1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Eastern Orthodox Christianity | 74,278,513 | 50.3 | 64,262,304 | 45.0 | 61,003,924 | 42.6 |

| Islam | 5,906,840 | 4.0 | 11,424,409 | 8.0 | 9,308,110 | 6.5[lower-alpha 2] |

| None, spiritual and minorities | 67,485,647 | 45.7 | 67,118,406 | 47.0 | 72,889,665 | 50.9 |

| Total population | 147,671,000 | 142,805,120 | 143,201,700 | |||

Line chart

Religions by ethnic group

| Russian Orthodox | Other Orthodox | Old Believers | Protestants | Catholics | Pentecostals | Simply Christians | Spiritual but not religious | Atheists | Simply Muslims | Sunni Muslims | Shia Muslims | Pagans / Tengrists | Buddhists | Religious Jews | Hindus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic Russians | 46 | 1.5 | <1 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | 27 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tatars | 5 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 9 | 55 | 3 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | <1 |

| Ukrainians | 45 | 2 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 0 | 7 | 26 | 12 | <1 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chuvashes | 58 | 4 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 22 | 8 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bashkirs | 1 | 0 | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 11 | 43 | 6 | <1 | 2 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

| Armenians | 35 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1.8 | 0 | 13 | 25 | 7 | 1 | <1 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Avars | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 24 | 66 | <1 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mordvins | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 14 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Germans | 18 | 2 | 0 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 1.2 | 5 | 34 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethnic Jews | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 25 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 0 |

| Kazakhs | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 7 | 54 | 7 | 1.1 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | <1 |

| Belarusians | 46 | 4.6 | 1.4 | <1 | 1.3 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <1 |

| All Russians | 41.1 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 4.1 | 25.2 | 13.0 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

Other surveys

- In 2016, Ipsos Global Trends, a multi-nation survey held by Ipsos and based on approximately 1,000 interviews, found that Christianity is the religion of 63% of the working-age, internet connected population of Russia; 62% stated they were Orthodox Christians, and 1% stated they were Catholic.[29] While 21% stated they were not religious, and 1% stated they were Muslims.[29]

- In 2015, the Pew Research Center estimated that 71% of Russians were Orthodox Christians, 15% were not religious, 10% were Muslim, 2% were Christians of other denominations, and 1% belonged to other religions.[30] At the same time, the centre published data from the European Social Survey 2004–2012 showing that the proportion of Orthodox Christians in Russia remained stable between 41% just after 2004, 46–50% around 2008, and 45% around 2012.[31]

- In 2015, the International Social Survey Programme estimated that 79.4% of Russians were Christians (78.3% Orthodox, 0.9% Catholics and 0.2% Protestants), 14.0% were not religious, 6.2% were Muslims, 0.1% were religious Jews, 0.1% were Hindus, and 0.3% belonged to other religions.[32]

- In 2018, according to a study jointly conducted by London's St Mary's University's Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society and the Institut Catholique de Paris, and based on data from the European Social Survey 2014–2016, Christianity is declining in Russia like in Western Europe. Among the 16 to 29 years-old Russians, 41% were Christians (40% Orthodox and 1% Protestant), 10% were of other religions (9% Muslim and 1% other), and 49% were not religious.[33]

- In 2013, the Russian Public Opinion Foundation estimated that 64% of Russians were Christians, 6% were Muslims, 25% were not religious and 4% were unsure about their belief.[34]

- In 2013, the Russian Academy of Sciences estimated that 79% of Russians were Orthodox Christians, 4% were Muslims, 9% were spiritual but not identifying themselves with any religion and 7% were atheists.[35]

- In 2012, the Levada Center estimated that 76% of Russians were Christians (74% Orthodox, 1% Catholic and 1% Protestant), 7% were Muslims, 1% were religious Jews, 10% were not religious, 5% were atheists and 2% were unsure about their belief.[36]

- In 2011, the Pew Research Center estimated that 73.6% of Russians were Christians.[37]

- In 2006, a survey conducted by the Japanese company Dentsu found that 47.5% of Russians were Orthodox Christians, 48.1% were not religious, and 4.4% belonged to other religions.[38]

- According to the Russian Analytical Centre for Sociology of Interethnic and Regional Relations (ISPI), the proportion of believers of the two largest religions in Russia remained stable between 1993 and 2000; Orthodox Christianity fluctuated between 46% in 1993, over 50% in the mid-1990s, and 49% in 2000, while Islam fluctuated between 7% in 1993 and 9% in 2000.[39]

Religions

Abrahamic religions

Christianity

Christianity was the religious self-identification of 47.1% of the Russian population in 2012.[1] Orthodox Christianity is the dominant religion of the country, and, besides it, Old Believers and Lutheranism also have had a considerable role in the multiethnic history of Russia. Evangelicalism and Catholicism (among Russians) are relatively recent additions to Christianity in Russia.[40]

Orthodox Christianity

Orthodox Christian believers constituted 42.6% of the total population of Russia in 2012. Most of them were members of the Russian Orthodox Church, while small minorities were Old Believers and Orthodox Christian believers who either did not belong to any church or belonged to non-Russian Orthodox churches (including the Armenian Apostolic Church and the Georgian Orthodox Church). Unaffiliated Orthodox Christians or non-Russian Orthodox Christians were 1.5% (2,100,000) of the total population. Minor Orthodox Christian churches are represented among ethnic minorities of Ukrainians, Georgians and Armenians. Unaffiliated Orthodox Christians and minorities of non-Russian Orthodox Christians comprised over 4% of the population in Tyumen Oblast (9%), Irkutsk Oblast (6%), the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (6%), Chelyabinsk Oblast (5%), Astrakhan Oblast (4%) and Chuvashia (4%).[1]

Russian Orthodoxy

In 2012, 58,800,000 people or 41% of the total population of Russia declared to believe in the Russian Orthodox Church. It was the religion of 21% to 40% of the population in most of the federal subjects of the country, with peaks of 41% to over 60% in Western Russia, including 41% to 60% in Yamalia and Perm Krai and over 60% in Kursk Oblast (69%), Voronezh Oblast (62%), Lipetsk Oblast (71%), Tambov Oblast (78%), Penza Oblast (63%), Ulyanovsk Oblast (61%), Mordovia (69%) and Nizhny Novgorod Oblast (69%).[1]

The contemporary Russian Orthodox Church (the Moscow Patriarchate; Russkaia Pravoslavnaia Tserkov'), despite it legally dates back only to 1949, claims to be the direct successor of the pre-revolutionary Orthodox Russian Church (Pravoslavnaia Rossiskaia Tserkov'). They have a slightly different name reflecting the distinction between Russkiy, ethnic Russians, and Rossiyane, citizens of Russia whether ethnic Russians or belonging to other ethnic groups. There are also a variety of small Orthodox Christian churches which claim as well to be the direct successors of the pre-revolutionary religious body, including the Russian Orthodox Catholic Church and the Russian Orthodox Autonomous Church. There have often been disputes between these churches and the Russian Orthodox Church over the reappropriation of disused churches, with the Russian Orthodox Church winning most cases thanks to the complicity of secular authorities.[20]

Old Believers

The Old Believers constituted 0.2% (400,000) of the total population of the country in 2012, with proportions higher than 1% only in Smolensk Oblast (1.6%), the Altai Republic (1.2%), Magadan Oblast (1%) and Mari El (1%).[1] The Old Believers are the religious group which experienced the most dramatic decline since the end of the Russian Empire and throughout the Soviet Union. In the final years of the empire they constituted 10% of the population of Russia, while today their number has shrunk to far less than 1% and there are few descendants of Old Believers' families who feel a cultural link with the faith of their ancestors.[41]

Old Believers' Church of Saint Nicholas on Tverskaya Square, Moscow.

Old Believers' Church of Saint Nicholas on Tverskaya Square, Moscow._02.jpg) Old Believers' Church of the Archangel Michael in Mikhailovskaya Sloboda.

Old Believers' Church of the Archangel Michael in Mikhailovskaya Sloboda.

.jpg) Armenian Church of the Holy Saviour in Derbent.

Armenian Church of the Holy Saviour in Derbent.- Armenian Church of Saint Catherine in Saint Petersburg.

Catholicism

Catholicism was the religion of 140,000 Russian citizens, about 0.1% of the total population, in 2012. They are concentrated in Western Russia with numbers ranging between 0.1% and 0.7% in most of the federal subjects of that region.[1] The number of "ethnic Catholics" in Russia, that is to say Poles and Germans, and smaller minorities, is continually declining due to emigration and secularisation. At the same time there has been a discrete rise of ethnic Russian converts to the Catholic Church.[24]

The Archdiocese of Moscow administers the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church in Russia. Further suffragan bishoprics exist in Irkutsk, Novosibirsk and Saratov. The Diocese of Irkutsk is in fact the largest Catholic bishopric on earth, covering an area of 9,960,000 squared kilometres. Almost all Russian Catholics adhere to the Latin Rite. However, the Catholic Church recognises the extremely small Russian Greek Catholic Church as a Byzantine Rite church sui juris ("of its own jurisdiction") in full communion with the Catholic Church.

Catholic Church of the Immaculate Heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Kemerovo.

Catholic Church of the Immaculate Heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Kemerovo. Catholic Church of the Nativity in Magadan.

Catholic Church of the Nativity in Magadan. Catholic Church of the Holy Trinity in Tobolsk.

Catholic Church of the Holy Trinity in Tobolsk.- Catholic Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross in Kazan.

Protestantism and other Christians

Various denominations of Protestantism, both historical and Evangelical, as well as Pentecostalism, were the religion of 0.2% (300,000) of the population of Russia in 2012. Their number was slightly more than 1% only in Tuva (1.8%), Udmurtia (1.4%) and the Altai Republic (1%).[1] Lutheranism has been on a continuous decline among Finnish and German ethnic minorities, while it has seen some Russian converts, so that some traditionally Finnish churches, like the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Ingria, today have more Russian than Finnish believers.[24] Adventists, Baptists, Methodists and Pentecostals are of relatively recent introduction, having at most 120 years of history in Russia.[41]

People who considered themselves Christians without affiliation to any church or denomination formed 4.1% (5,900,000) of the population, with numbers ranging between 1% to 8% in most of Russia's federal subjects, and over 8% only in Nenetia (14%), North Ossetia–Alania (10%), Tver Oblast (9%) and the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (9%).[1] Jehovah's Witnesses were estimated to have 255,000 believers in Russia in the mid-2000s.[42]

Pentecostal worship in Murmansk.

Pentecostal worship in Murmansk.

Seventh-day Adventist church in Nizhny Novgorod.

Seventh-day Adventist church in Nizhny Novgorod. Lutheran Church of Saint Anne in Saint Petersburg.

Lutheran Church of Saint Anne in Saint Petersburg.

Islam

Islam is the second largest religion in Russia after Orthodox Christianity.[1] It is the historicaly dominant religion among some Caucasian ethnic groups (notably the Chechens, the Ingush and the Adyghe), and some Turkic peoples (notably the Tatars and the Bashkirs).[1]

In 2012, Muslims in Russia were 9,400,000 or 6.5% of the total population. However, the Arena Atlas did not survey the populations of two federal subjects with Islamic majorities which together had a population of nearly 2 million, namely Chechnya and Ingushetia,[1] thus the total number of Muslims may be slightly larger. Among these Muslims, 6,700,000 or 4.6% of the total population of Russia were not affiliated with any Islamic schools and branches. This is mainly because it is not essential for Muslims to be affiliated with any specific sect or organisation. Those who are unaffiliated are mostly Sunni Muslims. These unaffiliated Muslims constitute significant percentages of over 10% in Kabardino-Balkaria (49%), Bashkortostan (38%), Karachay-Cherkessia (34%), Tatarstan (31%), Yamalia (13%), Orenburg Oblast (11%), Adygea (11%) and Astrakhan Oblast (11%). Most of the regions of Siberia have an unaffiliated Muslim population of 1% to 2%.[1]

Sunni Islam was the religion of 2,400,000 of the Muslims, or 1.6% of the total population of Russia. It had significant following of more than 10% of the population only in Dagestan (49%) and Karachay-Cherkessia (13%). Percentages higher than 2% are found in Kabardino-Balkaria (5%), Yugra (Khantia-Mansia) (5%), Yamalia (4%), Astrakhan Oblast (3%), Chelyabinsk Oblast (3%) and Tyumen Oblast (2%). Yakutia had a population of Sunnis ranging between 1% and 2%. Many other federal subjects had a Muslim population of 0.1% to 0.9%.[1] Shia Islam, otherwise, was a branch of 300,000 people, or 0.2% of the total population of Russia. It was primarily represented in Dagestan (2%), Adygea (1%), Karachay-Cherkessia (1%), Kabardino-Balkaria (1%), Novgorod Oblast (1%), Penza Oblast (1%), Tatarstan (1%) and Yugra (1%).[1]

The federal subjects of Russia with an Islamic absolute majority—more than 50%—were Chechnya, Ingushetia, Dagestan (82.6%), Kabardino-Balkaria (55.4%) and Tatarstan (55%). Significant percentages (over 5%) were found in Karachay-Cherkessia (48.0%), Bashkortostan (38.6%), Yamalia (17.4%), Astrakhan Oblast (14.6%), Adygea (12.6%), Orenburg Oblast (13.9%) and Yugra (10.9%).[1]

Mosque in Dzerzhinsk.

Mosque in Dzerzhinsk.

Mosque in Kinzebulatovo.

Mosque in Kinzebulatovo. Mosque in Kuluyevo, along the Miass River, in Chelyabinsk.

Mosque in Kuluyevo, along the Miass River, in Chelyabinsk.

Judaism

In 2012 there were 140,000 religious Jews in Russia,[1] while the number of ethnic Jews was significantly larger. Indeed, most ethnic Jews in Russia are not Jewish by religion, Judaism being the religion of just a minority of ethnic Jews; most of them are atheists and not religious, many are Christians, and a significant proportion of them are Buddhists.[43] In 2012, only 13% of ethnic Jews believed in Judaism, 13% were Orthodox Christians, 4% simply Christians, 27% atheists, 25% spiritual but not religious, 4% Buddhists and 3% Pagans.[1] Religious Jews were mostly concentrated in Kamchatka Krai (0.4%), Saint Petersburg (0.4%), Kursk Oblast (0.4%), Khabarovsk Krai (0.3%), Stavropol Krai (0.3%), Buryatia (0.2%), the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (0.2%), Kalmykia (0.2%) and Kabardino-Balkaria (0.2%).[1]

Ethnic and shamanic religions, Paganism and Tengrism

Paganism and Tengrism, counted together as "traditional religions of the forefathers"[2] were the third-largest religious group after Christianity and Islam, with 1,700,000 believers or 1.2% of the total population of Russia in 2012.[1] These religions are protected under the 1997 law, whose commentary specifies that "other religions and creeds which constitute an inseparable part of the historical heritage of Russia's peoples" also applies to "ancient Pagan cults, which have been preserved or are being revived".[4] Tengrism is a term which encompasses the traditional ethnic and shamanic religions of the Turkic and Mongolic peoples, and modern movements reviving them in Russia. Paganism in Russia is primarily represented by the revival of the ethnic religions of the Russians (Slavic), the Ossetians (Scythian), but also by those of Caucasian and Finno-Ugric ethnic minorities.

In 2012, Rodnovery, Caucasian Neopaganism, and Ossetian Uatsdin were represented by significant numbers of believers in North Ossetia–Alania (29%), Karachay-Cherkessia (12%), Kabardino-Balkaria (3%), Orenburg Oblast (over 3%), Kemerovo Oblast (over 3%), 2% to 3% in Dagestan, Astrakhan Oblast, Kaluga Oblast, Tyumen Oblast, Irkutsk Oblast and Magadan Oblast. The Slavic Native Faith was also present in many of the federal subjects of Western Russia in percentages ranging between 1% and 2%.[1]

The Slavic Native Faith (Rodnovery) alone represented 44% of the followers of the "traditional religions of the forefathers", thus approximately 750,000 people.[2] Rodnover organisations include the Union of Slavic Rodnover (Native Faith) Communities headquartered in Kaluga. The Moscow Community was the first to be registered by the state in 1994. Russian Rodnovers believe in Rod, the supreme God, and in lesser deities who include Perun and Dazhbog. Russian centers of Rodnovery are situated also in Dolgoprudny, Pskov and other cities, and Moscow has several shrines.[44]

Uralic Neopaganism is practised by Finno-Ugric ethnic minorities (primarily the Mari, the Mordvins, the Udmurts and the Komi). Among these peoples, Paganism survived as an unbroken tradition throughout the Soviet period.[4] The Mari Native Faith was practised by 6% of the population of Mari El in 2012.[1] Other studies reported a higher proportion of 15%.[45] Paganism was practised by between 2% and 3% of the population of Udmurtia (Udmurt Vos) and Perm Krai, and by between 1% and 2% of the population of the Komi Republic.[1]

Paganism is supported by the governments of some federal subjects, for instance Mari El. Although Paganism often faces the hostility of the Orthodox clergy, Patriarch Alexy II stressed that Protestant missionaries pose a greater danger than ethnic religions, and the latter should be respected.[46] Pagans have faced violence in some Islamic regions of the Caucasus. For instance, Aslan Tsipinov was murdered by Islamists in 2010, in Kabardino-Balkaria. Months before his death, Tsipinov was intimated by the extremists to stop his work of popularisation of Circassian (Kabardian) Pagan rituals.[47]

Tengrism and Turco-Mongol shamanic religions are found primarily in Siberia and the Russian Far East. In 2012, 13% of the inhabitants of the Altai Republic believed in indigenous religions—which include Burkhanism or "White Faith"[48]—, like 13% in Yakutia, 8% in Tuva, 3% in Kalmykia, between 2% and 3% in Khakassia, Buryatia and Kamchatka.[1] The Arena Atlas did not count the population of Chukotka, where much of the Chukchi practise their indigenous religion.[49]

Fire ceremony for Ysyakh, the Yakut New Year.

Fire ceremony for Ysyakh, the Yakut New Year. Aal Luuk Mas, Yakut world tree, symbolising the three levels of reality.

Aal Luuk Mas, Yakut world tree, symbolising the three levels of reality. Yakut ritual dance in circle.

Yakut ritual dance in circle.- Buryat shaman Budazhap Shiretorov, head of the Altan Serge religious community.

A dom archi (дом арчы) or archi djete (арчы дьиэтэ), a Tengrist church in Yakutsk.

A dom archi (дом арчы) or archi djete (арчы дьиэтэ), a Tengrist church in Yakutsk.

Mordvin ritual performance.

Mordvin ritual performance. College of Mari priests (kart).

College of Mari priests (kart). Russian Rodnover shrine in Kaluga.

Russian Rodnover shrine in Kaluga.

Eastern religions

Buddhism

In 2012, Buddhism was practised by 700,000 people in Russia, or 0.5% of the total population.[1] It is the traditional religion of some Turkic and Mongolic ethnic groups in Russia (the Kalmyks, the Buryats and the Tuvans). In 2012 it was the religion of 62% of the total population of Tuva, 38% of Kalmykia and 20% of Buryatia.[1] Buddhism also has believers accounting for 6% in Zabaykalsky Krai, primarily consisting in ethnic Buryats, and of 0.5% to 0.9% in Tomsk Oblast and Yakutia. Buddhist communities may be found in other federal subjects of Russia, between 0.1% and 0.5% in Sakhalin Oblast, Khabarovsk Krai, Amur Oblast, Irkutsk Oblast, Altay, Khakassia, Novosibirsk Oblast, Tomsk Oblast, Tyumen Oblast, Orenburg Oblast, Arkhangelsk Oblast, Murmansk Oblast, Moscow and Moscow Oblast, Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast, and in Kaliningrad Oblast.[1] In cities like Moscow, Saint Petersburg and Samara, often up to 1% of the population identify as Buddhists.[42]

Buddhism in Russia is almost exclusively of the Tibetan Vajrayana schools, especially Gelug but increasingly also Nyingma and Kagyu (Diamond Way Buddhism). There are many Russian converts, and the newer schools have been often criticised by representatives of the Gelug as the result of a Russianised (Rossiysky) Buddhism and of Western Buddhist missionaries.[51]

Kalmyk Burkhan Bakshin Altan Sume in Elista.

Kalmyk Burkhan Bakshin Altan Sume in Elista.- Pavilions of the Buryat Ivolginsky Datsan in Ivolginsk.

- Visitors at Ustuu-Huree, a Tuvan Buddhist monastery in Chadan.

Datsan Gunzechoinei in Saint Petersburg, the northernmost Buddhist temple in Russia.

Datsan Gunzechoinei in Saint Petersburg, the northernmost Buddhist temple in Russia.

Hinduism

Hinduism, especially in the forms of Krishnaism, Vedism and Tantrism, but also in other forms, has gained a following among Russians since the end of the Soviet period,[10] primarily through the missionary work of itinerant gurus and swamis, and organisations like the International Society for Krishna Consciousness and the Brahma Kumaris. The Tantra Sangha originated in Russia itself. The excavation of an ancient idol representing Vishnu in the Volga region in 2007 fueled the interest for Hinduism in Russia.[52]

However, Russian Hindus face the hostility of the Russian Orthodox Church. In 2011, prosecutors in Tomsk unsuccessfully tried to outlaw the Bhagavad-Gītā As It Is, the central text of the Krishnaite movement, on charge of extremism.[53] Russian Krishnaites in Moscow have long struggled for the construction of a large Krishna temple in the capital, which would compensate premises which were assigned to them in 1989 and later confiscated for municipal construction plans; the allocation of land for the temple has been repeatedly hindered and delayed, and Archbishop Nikon of Ufa asked the secular authorities to prevent the construction "in the very heart of Orthodox Russia" of an "idolatrous heathen temple to Krishna".[54] In August 2016, the premises of the Divya Loka monastery, a Vedic monastery founded in 2001 in Nizhny Novgorod, were dismantled by local authorities after having been declared illegal in 2015.[55]

Hinduism in Russia was practised by 140,000 people, or 0.1% of the total population, in 2012. It constituted 2% of the population in the Altai Republic, 0.5% in Samara Oblast, 0.4% in Khakassia, Kalmykia, Bryansk Oblast, Kamchatka, Kurgan Oblast, Tyumen Oblast, Chelyabinsk Oblast, 0.3% in Sverdlovsk Oblast, 0.2% to 0.3% in Yamalia, Krasnodar Krai, Stavropol Krai, Rostov Oblast, Sakhalin Oblast, and 0.1% to 0.2% in other federal subjects.[1]

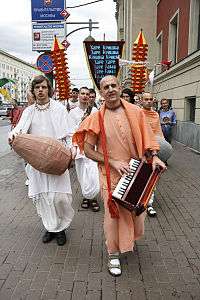

Hindus in Moscow celebrating Ratha Yatra.

Hindus in Moscow celebrating Ratha Yatra. Crowds celebrating Ratha Yatra in Moscow.

Crowds celebrating Ratha Yatra in Moscow. Hare Krishna devotees in the streets of Moscow.

Hare Krishna devotees in the streets of Moscow. Hare Krishna devotees distributing vegetarian meals.

Hare Krishna devotees distributing vegetarian meals.

Taoism

Taoism started to be disseminated in Russia after the end of the Soviet Union, particularly through the work of Master Alex Anatole, a Russian himself and Taoist priest, founder of the Center of Traditional Taoist Studies, which has been active in Moscow since 2002.[56] Another branch present in Russia is Wuliu Taoism, headquartered in Saint Petersburg since 2007.[57]

New religious and spiritual movements

In modern Russia, "all kinds of occult, Pagan and pseudo-Christian faiths are widespread". Some of them are "disciplined organisations with a well-defined membership".[42] The scholars of religion Sergei Filatov and Roman Lunkin, estimated in the mid-2000s that well-organised new religious movements had about 300,000 members. Nevertheless, well-organised movements constitute only "a drop in the 'new religious' ocean". Most of them are indeed "amorphous, eclectic and fluid",[42] difficult to measure, concerned with health, healing, and lifestyle, made up of fragments borrowed from Eastern religions like Buddhism, Hinduism and yoga. According to Filatov and Lunkin, these movements, albeit mostly unorganised, represent a "self-contained system" rather than a "transitional stage on the way to some other religion".[58]

Native new religious movements of Russia are Fourth Way, Rerikhism, Ivanovism, Ringing Cedars' Anastasianism, and others. Rerikhism, which was started before the perestroika, is a paradigmatic example of a movement which adapts Eastern religious beliefs to the conditions of contemporary Russia. It is not a centrally structured movement, but takes the form of a dust of clubs and associations.[58] Another movement, Ivanovism, is a system of healing through cold and relationship between humanity and nature founded by the mystic Porfiry Ivanov (1898–1983), called "messenger of the Cosmos" by his followers. His disciples, the Ivanovites, are recognisable by their lightweight clothing and sandals worn in winter.[59] Western Theosophical Society, Anthroposophical Society and other movements are also represented. Other movements rely upon astrology, which is believed by about 60% of Russians, emphasising the imminent start of the Age of Aquarius, the end of the world as it is currently known, and the formation of a superior "Aquarian race".[58]

- International Center of the Roerichs in Moscow.

Mother of the World (1924), Nicholas Roerich.

Mother of the World (1924), Nicholas Roerich. Agni Yoga (1928–1930), Nicholas Roerich.

Agni Yoga (1928–1930), Nicholas Roerich.- Golod pyramid under construction in Bolshoye Sidelnikovo, Sverdlovsk Oblast.

Church of Scientology in Moscow.

Church of Scientology in Moscow.

Freedom of religion

According to some Western commentators, respect for freedom of religion by secular authorities has declined in Russia since the late 1990s and early 2000s.[7][8] In 2006, a Mari Pagan priest, Vitaly Tanakov, was successfully convicted of extremism and sentenced to 120 hours of compulsory labour for having published a politico-religious tract, A Priest Speaks (Onajeng Ojla), which in 2009 was added to the federal list of material deemed "extremist".[60] In 2011 there was an unsuccessful attempt to ban the Bhagavad-Gītā As It Is on the same charge.[53] In August 2016, the premises of a Vedic monastery founded in 2001 in Nizhny Novgorod were demolished by local authorities after having been declared illegal in 2015.[61] It has been observed that the categories of "extremist" and "totalitarian sect" have been consistently used to try to outlaw religious groups which the Russian Orthodox Church classifies as "not traditional", including the newest Protestant churches and Jehovah's Witnesses.[62] There is a ban of Jehovah's Witnesses activities in Russia.[63]

In 2017, a report from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom stated that: "The Russian government views independent religious activity as a major threat to social and political stability, an approach inherited from the Soviet period".[64] Thus, for the first time, the USCIRF classified Russia as one of the world's worst violators of freedom of religion, a "country of particular concern" under the International Religious Freedom Act. The report also affirmed that Russia "is the sole state to have not only continually intensified its repression of religious freedom ..., but also to have expanded its repressive policies. ...Those policies, ranging from administrative harassment to arbitrary imprisonment to extrajudicial killing, are implemented in a fashion that is systematic, ongoing, and egregious".[64]

Bhagavad Gita trial

.jpg)

In 2011, a group linked to the Russian Orthodox Church demanded a ban of the Bhagavad-Gītā As It Is, the book of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, in Tomsk Oblast, on charge of extremism. The case was eventually dismissed by the federal judge on 28 December 2011.[65]

The Russian ambassador Alexander Kadakin condemned the "madmen" who sought the ban, and underlined that Russia is a secular country.[66] To protest the attempted ban, 15,000 Indians in Moscow, and followers of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness throughout Russia, appealed to the government of India asking an intervention to resolve the issue.[67] The move triggered strong protests by members of the Parliament of India who wanted the government to take a strong position. The final court hearing in Tomsk was then scheduled on 28 December, after the court agreed to seek the opinion of the Tomsk ombudsman on human rights and of Indologists from Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[68]

See also

![]()

Notes

- ↑ Including Old Believers (0.2%), Protestantism (0.2%), and Catholicism (0.1%).

- 1 2 The Sreda Arena Atlas 2012 did not count the populations of two Muslim-majority federal subjects of Russia, namely Chechnya and Ingushetia, which together had a population of nearly 2 million, thus the proportion of Muslims may be slightly underestimated.[1]

- ↑ The category included Rodnovers accounting for 44%, Hinduists accounting for 0.1%, and other Pagan religions and Siberian Tengrists and shamans accounting for the rest.[2]

- ↑ Including Judaism (0.1%) and other unspecified religions.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 "Арена: Атлас религий и национальностей" [Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities] (PDF). Среда (Sreda). 2012. See also the results' main interactive mapping and the static mappings: "Religions in Russia by federal subject" (Map). Ogonek. 34 (5243). 27 August 2012. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. The Sreda Arena Atlas was realised in cooperation with the All-Russia Population Census 2010 (Всероссийской переписи населения 2010) and the Russian Ministry of Justice (Минюста РФ).

- 1 2 3 4 Filina, Olga Filina (30 August 2012). "Mapping Russia's Religious Landscape". Russia Beyond. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 Bourdeaux 2003, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 Fagan 2013, p. 127.

- ↑ Bourdeaux 2003, p. 46.

- ↑ Bourdeaux 2003, pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 Uzzell 2000, p. 168: "Religious freedom grew steadily in Russia from about the mid-1980s to approximately 1993. ... The real religious freedom that existed in practice was ... a result of the turmoil and chaos of the early 1990s, which prevented the Russian elite from keeping a steady hand on things. That hand is firmer now, and there has been a steady deterioration of religious freedom over the past five years. In 1994, the first provincial law restricting the rights of religious minorities was passed, in Tula, about two hundred miles south of Moscow. About one-third of Russia's provinces have passed similar laws since then, and in 1997 the national government passed a law explicitly distinguishing between first-class 'religious organizations' and second-class 'religious groups', which have far fewer rights".

- 1 2 Knox 2008, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Kharitonova 2015, passim.

- 1 2 Tkatcheva 1994, passim.

- 1 2 Bennett 2011, pp. 27–28; Borenstein 1999, p. 441.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, p. 1.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 Rosenthal 1997, p. 10.

- ↑ Rosenthal 1997, pp. 135 ff, 153 ff, 185 ff.

- 1 2 3 4 Fagan 2013, p. 3.

- 1 2 Balzer 2015, pp. 6–11.

- ↑ Balzer 2015, p. 7.

- 1 2 Fagan 2013, p. 129.

- ↑ Armes, Keith (1993). "Chekists in Cassocks: The Orthodox Church and the KGB" (PDF). Demokratisatsiya (4). pp. 72–83. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 Filatov & Lunkin 2006, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Filatov & Lunkin 2006, pp. 40–43.

- 1 2 3 Filatov & Lunkin 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Filatov & Lunkin 2006, p. 40.

- ↑ Filatov & Lunkin 2006, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Balzer 2015, p. 12: reports data from a research held by the Russian Ministry of Education in 1998.

- ↑ European Social Survey 2007–2009. Data reported in Kreko, Peter; Szabados, Krisztian (2 April 2010). "Terror Attacks: Enflaming Right-Wing Extremism Among Russians and Muslim Minority". Political Capital – Policy Research and Consulting Institute. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Religion, Ipsos Global Trends". Ipsos. 2017. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. About Ipsos Global Trends survey

- ↑ "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe" (PDF). Pew Research Center. 10 May 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2017.

- ↑ "In recent years, Orthodox shares fairly stable". Pew Research Center. 8 May 2017. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017.

- ↑ "Country-specific religious affiliation or denomination: Russia - weighted". International Social Survey Programme: Work Orientations IV - ISSP 2015 (6770). doi:10.4232/1.12848 – via GESIS.

- ↑ Bullivant, Stephen (2018). "Europe's Young Adults and Religion: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014-16) to inform the 2018 Synod of Bishops" (PDF). St Mary's University's Benedict XVI Centre for Religion and Society; Institut Catholique de Paris. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Ценности: религиозность" [Values: Religiosity] (in Russian). Фонд Общественное Мнение, ФОМ (Public Opinion Foundation). 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Dobrynina, Yekaterina (15 January 2013). "Вера и надежды: Социологи выяснили, каким богам россияне молятся и во что по-настоящему верят" [Faith and hope: Sociologists have found out what kind of gods Russians are praying to and what they actually believe in]. Rossiyskaya Gazeta (in Russian).

- ↑ "В России 74% православных и 7% мусульман" [In Russia, 74% are Orthodox and 7% Muslims] (in Russian). Levada Center. 17 December 2012. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012.

- ↑ "Global Christianity – A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Christian Population". Pew Research Center. 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "世界60カ国価値観データブック" [Sixty World Countries' Values Databook]. Dentsu. 9 June 2006.

- ↑ Analytical Center for Sociology of Interethnic and Regional Relations (ISPI). Data reported in Kon, Roman Mikhailovich (2008). "Динамика и тенденции развития сект в России [Dynamics and trends in the development of sects in Russia]". Введение в сектоведение [Introduction to Sectology]. Nizhny Novgorod Theological Seminary. ISBN 9785903657094.

- ↑ Balzer 2015, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 Filatov & Lunkin 2006, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 Filatov & Lunkin 2006, p. 38.

- ↑ Filatov & Lunkin 2006, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Rodoslav; Smagoslav; Rudiyar (22 June 2001). "Московская Славянская Языческая Община" [Moscow Slavic Pagan Community]. paganism.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ↑ von Twickel, Nikolaus (7 July 2009). "Europe's Last Pagans Worship in Mari-El Grove". The St. Petersburg Times (1489). Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, p. 128.

- ↑ Dzutsati, Valery (3 January 2011). "High-profile Murders in Kabardino-Balkaria Underscore the Government's Inability to Control Situation in the Republic". Eurasia Daily Monitor. 8 (1). Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ↑ Balzer 2015, pp. 245–246.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, p. 148.

- ↑ Grechin, B. S. (2016). "Апология русского буддизма" [Apology of Russian Buddhism] (PDF) (in Russian). Yaroslavl: Sangye Chho Ling. ISBN 9781311551276. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2017.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ "Ancient Vishnu idol found in Russian town". The Times of India. 4 January 2007. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011.

- 1 2 Fagan 2013, p. 168.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, p. 99.

- ↑ Sibireva, Olga; Verkhovsky, Alexander (10 May 2017). "Freedom of Conscience in Russia: Restrictions and Challenges in 2016". SOVA - Center for Information and Analysis. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018.

- ↑ "Official website of the Centre of Traditional Taoist Studies".

- ↑ "Official website of Wuliu Taoism in Saint Petersburg".

- 1 2 3 Filatov & Lunkin 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ Rosenthal 1997, pp. 199, 368.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, p. 166.

- ↑ Sibireva, Olga; Verkhovsky, Alexander (10 May 2017). "Freedom of Conscience in Russia: Restrictions and Challenges in 2016". SOVA - Center for Information and Analysis. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018.

- ↑ Fagan 2013, pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Bennetts, Marc (23 May 2018). "Russia is rounding up Jehovah's Witnesses — Are other groups next?". Newsweek. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- 1 2 "USCIRF Countries of Particular Concern (CPC): Russia" (PDF). U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. 26 April 2017.

- ↑ "Gita row: Russia court refuses to ban Bhagvad Gita". NDTV. 28 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012.

- ↑ "Declare Bhagavad Gita as national book, demands BJP". Hindustan Times. 20 December 2011. Archived from the original on 20 December 2011.

- ↑ "Gita row snowballs, India raises issue at 'highest levels'". The Economic Times. 20 December 2011. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012.

- ↑ "Gita ban: Russian court suspended verdict till 28 December". The Statesman. Press Trust of India. 19 December 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012.

Sources

- Balzer, Marjorie Mandelstam (2015). Religion and Politics in Russia: A Reader. Routledge. ISBN 9781317461128.

- Bennett, Brian P. (2011). Religion and Language in Post-Soviet Russia. Routledge. ISBN 9781136736131.

- Borenstein, Eliot (1999). "Suspending Disbelief: "Cults" and Postmodernism in Post-Soviet Russia"". In Barker, Adele Marie. Consuming Russia: Popular Culture, Sex, and Society Since Gorbachev. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822323136.

- Bourdeaux, Michael (2003). "Trends in Religious Policy". Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. Taylor and Francis. pp. 46–52. ISBN 9781857431377.

- Fagan, Geraldine (2013). Believing in Russia: Religious Policy After Communism. Routledge. ISBN 9780415490023.

- Filatov, Sergei; Lunkin, Roman (2006). "Statistics on Religion in Russia: The Reality behind the Figures" (PDF). Religion, State & Society. 34 (1). Routledge. doi:10.1080/09637490500459875. ISSN 0963-7494.

- Kharitonova, Valentina (2015). "Revived Shamanism in the Social Life of Russia" (PDF). Folklore. 62. FB and Media Group of LM. pp. 37–54. doi:10.7592/FEJF2015.62. ISSN 1406-0949.

- Knox, Zoe (2008). "Religious Freedom in Russia: The Putin Years". In Steinberg, Mark D.; Wanner, Catherine. Religion, Morality, and Community in Post-Soviet Societies. Indiana University Press. pp. 281–314. ISBN 9780253220387.

- Rosenthal, Bernice Glatzer, ed. (1997). The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801483318.

- Tkatcheva, Anna (1994). "Neo-Hindu Movements and Orthodox Christianity in Post-Communist Russia". India International Centre Quarterly. 21 (2/3). pp. 151–162. JSTOR 23003642.

- Uzzell, Lawrence (2000). "Advancing Freedom of Belief in Russia". In Vanden Heuvel, William. The Future of Freedom in Russia. Templeton Foundation Press. ISBN 9781890151430.

External links

- Online "The Reference Book on All Religious Branches and Communities in Russia by Dr. Igor Popov (in Russian)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)