Baltic languages

| Baltic | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Balts |

| Geographic distribution | Northern Europe |

| Linguistic classification |

Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | bat |

| Linguasphere | 54= (phylozone) |

| Glottolog |

None east2280 (East Baltic)[1] prus1238 (Prussian)[2] |

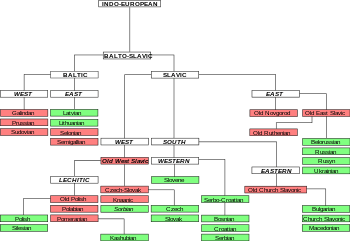

The Baltic languages belong to the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. Baltic languages are spoken by the Balts, mainly in areas extending east and southeast of the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe.

Scholars usually regard them as a single language family divided into two groups: Western Baltic (containing only extinct languages) and Eastern Baltic (containing two living languages, Lithuanian and Latvian). The range of the Eastern Baltic linguistic influence once possibly reached as far as the Ural Mountains, but this hypothesis has been questioned.[3][4][5]

Old Prussian, a Western Baltic language that became extinct in the 18th century, ranks as the most archaic of the Baltic languages.[6]

Although morphologically related, the Lithuanian, Latvian and, particularly, Old Prussian vocabularies differ substantially from one another, and as such they are not mutually intelligible, mainly due to a substantial number of false friends, and foreign words, borrowed from surrounding language families, which are used differently.

Branches

The Baltic languages are generally thought to form a single family with two branches, Eastern and Western. However, these two branches are sometimes classified as independent branches of Balto-Slavic.[2]

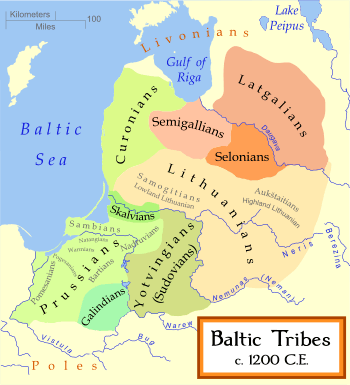

Western Baltic languages †

- (Western) Galindian †

- Old Prussian †

- Sudovian (Yotvingian) †

- ? Skalvian † (unattested)

Eastern Baltic languages

- Latvian (~2–2.5 million speakers, whereof ~1.39 million native speakers, 0.5–1 million ethnic Russian speakers, 0.15 million others)

- Lithuanian (~3.9 million speakers)

- Selonian †

- Semigallian †

- Old Curonian (sometimes considered Western Baltic) †

Dniepr Baltic languages †

- (Eastern) Galindian (the language of the Eastern Galindians, also known by its name in Russian: Голядь Golyad') †[7]

(† — extinct language)

Prehistory and history

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

|

|

It is believed that the Baltic languages are among the most archaic of the currently remaining Indo-European languages, despite their late attestation.

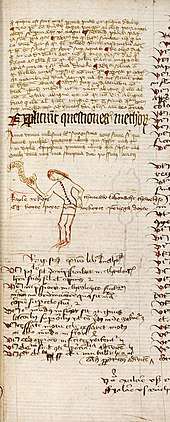

Although the various Baltic tribes were mentioned by ancient historians as early as 98 B.C., the first attestation of a Baltic language was about 1350, with the creation of the Elbing Prussian Vocabulary, a German to Prussian translation dictionary. Lithuanian was first attested in a hymnal translation in 1545; the first printed book in Lithuanian, a Catechism by Martynas Mažvydas was published in 1547 in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia). Latvian appeared in a hymnal in 1530 and in a printed Catechism in 1585.

One reason for the late attestation is that the Baltic peoples resisted Christianization longer than any other Europeans, which delayed the introduction of writing and isolated their languages from outside influence.

With the establishment of a German state in Prussia, and the eradication or flight of much of the Baltic Prussian population in the 13th century, the remaining Prussians began to be assimilated, and by the end of the 17th century, the Prussian language had become extinct.

During the years of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795), official documents were written in Polish, Ruthenian and Latin.

After the Partitions of Commonwealth, most of the Baltic lands were under the rule of the Russian Empire, where the native languages or alphabets were sometimes prohibited from being written down or used publicly in a Russification effort (see Lithuanian press ban for the ban in force from 1865 to 1904).

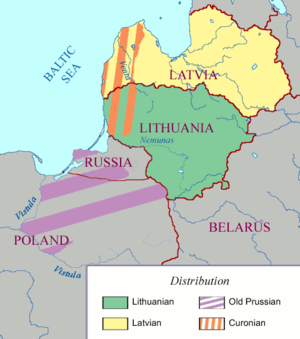

Geographic distribution

Speakers of modern Baltic languages are generally concentrated within the borders of Lithuania and Latvia, and in emigrant communities in the United States, Canada, Australia and the countries within the former borders of the Soviet Union.

Historically the languages were spoken over a larger area: west to the mouth of the Vistula river in present-day Poland, at least as far east as the Dniepr river in present-day Belarus, perhaps even to Moscow, and perhaps as far south as Kiev. Key evidence of Baltic language presence in these regions is found in hydronyms (names of bodies of water) that are characteristically Baltic. The use of hydronyms is generally accepted to determine the extent of a culture's influence, but not the date of such influence.

The Mordvinic languages, spoken mainly along western tributaries of the Volga, show several dozen loanwords from one or more Baltic languages. These may have been mediated by contacts with the Eastern Balts along the river Oka.[8]

The eventual expansion of the use of Slavic languages in the south and east, and Germanic languages in the west, reduced the geographic distribution of Baltic languages to a fraction of the area that they formerly covered. The Russian geneticist Oleg Balanovsky speculated that there is a predominance of the assimilated pre-Slavic substrate in the genetics of East and West Slavic populations, according to him the common genetic structure which contrasts East Slavs and Balts from other populations may suggest that the pre-Slavic substrate of the East Slavs consists most significantly of Baltic-speakers, which predated the Slavs in the cultures of the Eurasian steppe according to archaeological references he cites.[9]

Though Estonia is included among the Baltic states due to its location, Estonian is a Uralic language and is not related to the Baltic languages, which are Indo-European.

Comparative linguistics

Genetic relatedness

The Baltic languages are of particular interest to linguists because they retain many archaic features, which are believed to have been present in the early stages of the Proto-Indo-European language.[10] However, linguists have had a hard time establishing the precise relationship of the Baltic languages to other languages in the Indo-European family.[11] Several of the extinct Baltic languages have a limited or nonexistent written record, their existence being known only from the records of ancient historians and personal or place names. All of the languages in the Baltic group (including the living ones) were first written down relatively late in their probable existence as distinct languages. These two factors combined with others have obscured the history of the Baltic languages, leading to a number of theories regarding their position in the Indo-European family.

The Baltic languages show a close relationship with the Slavic languages, and are grouped with them in a Balto-Slavic family by most scholars. This family is considered to have developed from a common ancestor, Proto-Balto-Slavic. Later on, several lexical, phonological and morphological dialectisms developed, separating the various Balto-Slavic languages from each other.[12][13] Although it is generally agreed that the Slavic languages developed from a single more-or-less unified dialect (Proto-Slavic) that split off from common Balto-Slavic, there is more disagreement about the relationship between the Baltic languages.

The traditional view is that the Balto-Slavic languages split into two branches, Baltic and Slavic, with each branch developing as a single common language (Proto-Baltic and Proto-Slavic) for some time afterwards. Proto-Baltic is then thought to have split into East Baltic and West Baltic branches. However, more recent scholarship has suggested that there was no unified Proto-Baltic stage, but that Proto-Balto-Slavic split directly into three groups: Slavic, East Baltic and West Baltic.[14][15] Under this view, the Baltic family is paraphyletic, and consists of all Balto-Slavic languages that are not Slavic. This would imply that Proto-Baltic, the last common ancestor of all Baltic languages, would be identical to Proto-Balto-Slavic itself, rather than distinct from it. In the 1960s Vladimir Toporov and Vyacheslav Ivanov made the following conclusions about the relationship between the Baltic and Slavic languages: a) Proto-Slavic language formed from the peripheral-type Baltic dialects; b) Slavic linguistic type formed later from the Baltic languages structural model; c) the Slavic structural model is a result of the Baltic languages structural model transformation. These scholars’ theses do not contradict the Baltic and Slavic languages closeness and from a historical perspective specify the Baltic-Slavic languages evolution.[16][17]

Finally, there is a minority of scholars who argue that Baltic descended directly from Proto-Indo-European, without an intermediate common Balto-Slavic stage. They argue that the many similarities and shared innovations between Baltic and Slavic are due to several millennia of contact between the groups, rather than shared heritage.[18]

Thracian hypothesis

The Baltic-speaking peoples likely encompassed an area in Eastern Europe much larger than their modern range: as in the case of the Celtic languages of Western Europe, they were reduced with invasions, exterminations and assimilations. Studies in comparative linguistics point to genetic relationship between the languages of the Baltic family and the following extinct languages:

The Baltic classification of Dacian and Thracian has been proposed by the Lithuanian scientist Jonas Basanavičius, who insisted this is the most important work of his life and listed 600 identical words of Balts and Thracians.[25][26] His theory included Phrygian in the related group, but this did not find support and was disapproved among other authors, such as Ivan Duridanov, whose own analysis found Phrygian completely lacking parallels in either Thracian or Baltic languages.[27]

The Bulgarian linguist Ivan Duridanov, who improved the most extensive list of toponyms, in his first publication claimed that Thracian is genetically linked to the Baltic languages[20] and in the next one he made the following classification:"The Thracian language formed a close group with the Baltic (resp. Balto-Slavic), the Dacian and the "Pelasgian" languages. More distant were its relations with the other Indo-European languages, and especially with Greek, the Italic and Celtic languages, which exhibit only isolated phonetic similarities with Thracian; the Tokharian and the Hittite were also distant. "[27] Of about 200 reconstructed Thracian words by Duridanov most cognates (138) appear in the Baltic languages, mostly in Lithuanian, followed by Germanic (61), Indo-Aryan (41), Greek (36), Bulgarian (23), Latin (10) and Albanian (8). The cognates of the reconstructed Dacian words in his publication are found mostly in the Baltic languages, followed by Albanian. Parallels have enabled linguists, using the techniques of comparative linguistics, to decipher the meanings of several Dacian and Thracian placenames with, they claim, a high degree of probability. Of 74 Dacian placenames attested in primary sources and considered by Duridanov, a total of 62 have Baltic cognates, most of which were rated "certain" by Duridanov.[28] For a big number of 300 Thracian geographic names most parallels were found between Thracian and Baltic geographic names in the study of Duridanov.[27][29][27] According to him the most important impression make the geographic cognates of Baltic and Thracian "the similarity of these parallels stretching frequently on the main element and the suffix simultaneously, which makes a strong impression".[29][20]

Some scholars,[30] including Toparov,[31] have found many linguistic similarities between Baltic and ancient Balkan languages pointing to the many close parallels between Dacian and Thracian placenames and those of the Baltic language-zone. A number of possible parallels of the Thracian ethnonym in Lithuania were not found in any other country, including the former capital Trakai (cf. Lith. Trakai, meaning "Thracians"), Trakininkai, Trakiškiai, Trakiškiemiai, Traksėda and others.[32] Other Slavic authors noted that Dacian and Thracian have much in common with Baltic onomastics and explicitly not in any similar way with Slavic onomastics, including cognates and parallels of lexical isoglosses, which implies a recent common ancestor.[33]

After creating a list of names of rivers and personal names with a high number of parallels, the Romanian linguist Mircea M. Radulescu classified the Daco-Moesian and Thracian as Baltic languages expanding to the south and also proposed such classification for Illyrian.[23] The German linguist Schall attributed a South Baltic classification to the Dacian language.[22] The Venezuelan-Lithuanian historian Jurate Rosales classifies Dacian and Thracian as Baltic languages.[21] The Czech archaeologist Kristian Turnvvald classified such languages as Danubian Baltic.[34]

The American linguist Harvey Mayer refers to both Dacian and Thracian as Baltic languages. Mayer claims that he extracted an unambiguous evidence for regarding Dacian and Thracian as more tied to Lithuanian than to Latvian.[19] In his first publication he claims to have sufficient evidence for classifying them as Baltoidic or at least "Baltic-like," if not exactly, Baltic dialects or languages[35][19] still maintaining a genetic link within a common language family. In the next and final publication he refers to them as South or East Baltic languages[36][19] and classifies Dacians and Thracians as "Balts by extension".[37] "Finally, I label Thracian and Dacian as East Baltic...The fitting of special Dacian and Thracian features (which I identified from Duridanov’s listings) into Baltic isogloss patterns so that I identified Dacian and Thracian as southeast Baltic. South Baltic because, like Old Prussian, they keep unchanged the diphthongs ei, ai, en, an (north Baltic Lithuanian and Latvian show varying percentages of ei, ai to ie, and en, an to ę, ą (to ē, ā) in Lithuanian, to ie, uo in Latvian). East Baltic because the Dacian word žuvete (now in Rumanian spelled juvete) has ž, not z as in west Baltic, and the Thracian word pušis (the Latin-Greek transcription shows pousis which, I believe, reflects -š-.) with zero grade puš- as in Lithuanian pušìs rather than with e-grade *peuš- as in Prussian peusē. Zero grade in this word is east Baltic, e-grade here is west Baltic, while the other word for “pine, evergreen”, preidē (Prussian and Dacian), priede (Latvian), is marginal in Lithuanian matched by no *peus- in Latvian."[36] In regards to other languages, he claims that Albanian is a descendant of Illyrian and escaped any heavy Baltic influence of Thracian.[37]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "East Baltic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Prussian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Marija Gimbutas 1963. The Balts. London : Thames and Hudson, Ancient peoples and places 33.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory, "Fatyanovo-Balanovo Culture", Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997

- ↑ David W. Anthony, "The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World", Princeton University Press, 2007

- ↑ Ringe, D., Warnow, T., Taylor, A., 2002. Indo-European and computational cladistics. Trans. Philos. Soc. 100, 59–129.

- ↑ Dini, P.U. (2000). Baltų kalbos. Lyginamoji istorija. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 61. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- ↑ Grünthal, Riho (2012). "Baltic loanwords in Mordvin" (PDF). A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia 266. pp. 297–343.

- ↑ П, Балановский О. "Генофонд Европы" (in Russian). KMK Scientific Press.

Прежде всего, это преобладание в славянских популяциях дославянского субстрата — двух ассимилированных ими генетических компонентов – восточноевропейского для западных и восточных славян и южноевропейского для южных славян...Можно с осторожностью предположить, что ассимилированный субстратмог быть представлен по преимуществу балтоязычными популяциями. Действительно, археологические данные указыва ют на очень широкое распространение балтских групп перед началом расселения славян. Балтскийсубстрату славян (правда, наряду с финно-угорским) выявляли и антропологи. Полученные нами генетические данные — и на графиках генетических взаимоотношений, и по доле общих фрагментов генома — указывают, что современные балтские народы являются ближайшими генетически ми соседями восточных славян. При этом балты являются и лингвистически ближайшими род ственниками славян. И можно полагать, что к моменту ассимиляции их генофонд не так сильно отличался от генофонда начавших свое широкое расселение славян. Поэтому если предположить,что расселяющиеся на восток славяне ассимилировали по преимуществу балтов, это может объяснить и сходство современных славянских и балтских народов друг с другом, и их отличия от окружающих их не балто-славянских групп Европы...В работе высказывается осторожное предположение, что ассимилированный субстрат мог быть представлен по преимуществу балтоязычными популяциями. Действительно, археологические данные указывают на очень широкое распространение балтских групп перед началом расселения славян. Балтский субстрат у славян (правда, наряду с финно-угорским) выявляли и антропологи. Полученные в этой работе генетические данные — и на графиках генетических взаимоотношений, и по доле общих фрагментов генома — указывают, что современные балтские народы являются ближайшими генетическими соседями восточных славян.

- ↑ Marija Gimbutas (1963). The balts, by marija gimbutas. Thames and hudson. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ Ancient Indo-European Dialects. University of California Press. pp. 139–151. GGKEY:JUG4225Y4H2. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory (1 April 1991). In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27616-7. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ Kortlandt, Frederik (2009), Baltica & Balto-Slavica, p. 5,

Though Prussian is undoubtedly closer to the East Baltic languages than to Slavic, the characteristic features of the Baltic languages seem to be either retentions or results of parallel development and cultural interaction. Thus I assume that Balto-Slavic split into three identifiable branches, each of which followed its own course of development.

- ↑ Derksen, Rick (2008), Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon, p. 20,

I am not convinced that it is justified to reconstruct a Proto-Baltic stage. The term Proto-Baltic is used for convenience’s sake.

- ↑ Dini, P.U. (2000). Baltų kalbos. Lyginamoji istorija. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 143. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- ↑ Бирнбаум Х. О двух направлениях в языковом развитии // Вопросы языкознания, 1985, № 2, стр. 36

- ↑ Hans Henrich Hock; Brian D. Joseph (1996). Language history, language change, and language relationship: an introduction to historical and comparative linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 53. ISBN 978-3-11-014784-1. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mayer 1996.

- 1 2 3 4 Duridanov 1969.

- 1 2 3 JŪRATĖ STATKUTĖ DE ROSALES EUROPOS ŠAKNYS IR MES, LIETUVIAI, pp. 43-70 (PDF).

- 1 2 Schall H., Sudbalten und Daker. Vater der Lettoslawen. In:Primus congressus studiorum thracicorum. Thracia II. Serdicae, 1974, S. 304, 308, 310

- 1 2 3 Radulescu M., The Indo-European position of lllirian, Daco-Mysian and Thracian: a historic Methodological Approach, 1987

- ↑ Dras. J. Basanavičius. Apie trakų prygų tautystę ir jų atsikėlimą Lietuvon

- ↑ Balts and Goths: the missing link in European history. Vydūnas Youth Fund.

- ↑ Daskalov, Roumen; Vezenkov, Alexander. Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume Three: Shared Pasts, Disputed Legacies. BRILL. ISBN 9789004290365.

- 1 2 3 4 Duridanov 1976.

- ↑ Duridanov 1969, pp. 95-96.

- 1 2 Duridanov 1985.

- ↑ Vyčinienė, Daiva. "RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN LITHUANIAN AND BALKAN SCHWEBUNGS-DIAPHONIE: INTERDISCIPLINARY SEARCH KEY". p. 122.

- ↑ Топаров В.Н., К фракийско-балтийским язьiковим параллелям. Балканское язьiкознание, М., 1973, s. 51, 52

- ↑ "Lietuvių tautos kilmės teorijų sąvadas". jurbarkopuslapiai.lt (in Lithuanian).

- ↑ ON. Trubachev, ‘Linguistics and ethnogenesis of the Slavs: the ancient Slavs as evi- denced by etymology and onomastics,’ journal oj'Inaeruropean Studies 13 (1985), pp. 203—256, here p. 215. On the other hand, certain isoglosses, particularly lexical ones, in Balkan Slavic languages have cognates in Baltic, but not in East Slavic languages. See D. Brozovic, ‘Doseljenje slavena i njihovi dodiri sa starosjediocima u svjetlu lingvistickih istraiivanja’ [The settlement of the Slavs and their contacts with the native population in the light of linguistic studies], in Simpozijum ‘Treaslavenski etnit‘lei elemenii na Balkanu u etnogenezi juinih Slovena”, odrian 24—26. oktobra 1968 u Mostaru [Symposium on Pre-Slavic ethnic elements on the Balkans and the ethnognesis of Southern Slavs; Mostar, 24–26 October 1968], ed. A. Benac (Sarajevo: Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine, 1969), 1313- 129—140, here pp. 151-152

- ↑ Turnvvald K., Die Balten des vorgeschichtlichen Mitteleuropas, Riga, 1968

- ↑ Mayer 1992.

- 1 2 Mayer 1999.

- 1 2 Mayer 1997.

References

- "Lithuania 1863-1893: Tsarist Russification and the Beginnings of the Modern Lithuanian National Movement - Strazas". www.lituanus.org. Retrieved 2017-10-05.

- Ernst Fraenkel (1950) Die baltischen Sprachen, Carl Winter, Heidelberg, 1950

- Joseph Pashka (1950) Proto Baltic and Baltic languages

- Lituanus Linguistics Index (1955–2004) provides a number of articles on modern and archaic Baltic languages

- Mallory, J. P. (1991) In Search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. New York: Thames and Hudson ISBN 0-500-27616-1

- Algirdas Girininkas (1994) "The monuments of the Stone Age in the historical Baltic region", in: Baltų archeologija, N.1, 1994 (English summary, p. 22). ISSN 1392-0189

- Algirdas Girininkas (1994) "Origin of the Baltic culture. Summary", in: Baltų kultūros ištakos, Vilnius: "Savastis" ISBN 9986-420-00-8"; p. 259

- Edmund Remys (2007) "General distinguishing features of various Indo-European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian", in: Indogermanische Forschungen; Vol. 112. Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter

- Mayer, H.E. (1992). "Dacian and Thracian as southern Baltoidic". Lituanus. Defense Language Institute, United States Department of Defense. 38 (2). ISSN 0024-5089.

- Mayer, H.E. (1996). "SOUTH BALTIC". Lituanus. 42 (2).

- Mayer, H.E. (1997). "BALTS AND CARPATHIANS". Lituanus. 43 (2).

- Duridanov, I. (1969). Die Thrakisch- und Dakisch-Baltischen Sprachbeziehungen.

- Duridanov, I. (1976). Ezikyt na Trakite.

- Duridanov, I. (1985). Die Sprache der Thraker.

- Mayer, H.E. (1999). "Dr. Harvey E. Mayer, February 1999".

Literature

- Stafecka, A. & Mikuleniene, D., 2009. Baltu valodu atlants: prospekts = Baltu kalbu atlasas: prospektas = Atlas of the Baltic languages: a prospect, Vilnius: Lietuvių kalbos institutas; Riga: Latvijas Universitates Latviesu valodas instituts. ISBN 9789984742496

External links

- Baltic Online from the University of Texas at Austin