Persian people

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 49,312,834 (61–65% of the total population)[1][2] | |

| Languages | |

| Persian, and closely related languages. | |

| Religion | |

| Primarily Shia Islam, as well as Irreligion, Christianity, the Bahá'í faith, Sunni Islam, Sufism, and Zoroastrianism. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranian peoples. | |

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group that make up over half the population of Iran.[3][2] They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language,[4][5][6] as well as closely related languages.[7]

The ancient Persians were a nomadic branch of the ancient Iranian population that entered the territory of modern-day Iran by the early 10th century BC.[8][9] Together with their compatriot allies, they established and ruled some of the world's most powerful empires,[10][11] well-recognized for their massive cultural, political, and social influence covering much of the territory and population of the ancient world.[12][13][14] Throughout history, the Persians have contributed greatly to various forms of art and science,[15][16][17] and own one of the world's most prominent literatures.[18]

In contemporary terminology, people of Persian heritage native specifically to present-day Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan are referred to as Tajiks, whereas those in the eastern Caucasus (primarily the present-day Republic of Azerbaijan), albeit heavily assimilated, are referred to as Tats.[19][20] However, historically, the terms Tajik, Tat, and Persian were synonymous and were used interchangeably,[19] and many of the most influential Persian figures hailed from outside Iran's present-day borders to the northeast in Central Asia and Afghanistan and to a lesser extent to the northwest in the Caucasus proper.[21][22]

Ethnonym

Etymology

The English term Persian derives from Latin Persia, itself deriving from Greek Persís (Περσίς),[23] a Hellenized form of Old Persian Pārsa (𐎱𐎠𐎼𐎿).[24] In the Bible, it is given as Parás (Hebrew: פָּרָס)—sometimes Paras uMadai (פרס ומדי; "Persia and Media")—within the books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemya.

A Greek folk etymology connected the name to Perseus, a legendary character in Greek mythology. Herodotus recounts this story,[25] devising a foreign son, Perses, from whom the Persians took the name. Apparently, the Persians themselves knew the story,[26] as Xerxes I tried to use it to suborn the Argives during his invasion of Greece, but ultimately failed to do so.

History of usage

Although Persis was originally one of the provinces of ancient Iran,[27] varieties of this term (e.g. Persia) were adopted through Greek sources and used as an official name for all of Iran for many years.[28] Thus, in the Western world, the term Persian came to refer to all inhabitants of the country.[28]

Some medieval and early modern Islamic sources also used cognates of the term Persian to refer to various Iranian peoples, including the speakers of the Khwarezmian language,[29] the Mazanderani language,[30] and the Old Azeri language.[31] 10th-century Iraqi historian Al-Masudi refers to Pahlavi, Dari and Azari as dialects of the Persian language.[32] In 1333, medieval Moroccan traveler and scholar Ibn Battuta referred to the people of Kabul as a specific sub-tribe of Persians.[33] Lady Mary (Leonora Woulfe) Sheil, in her observation of Iran during the Qajar era, describes Persians, Kurds, and Leks to identify themselves as "descendants of the ancient Persians".[20]

On March 21, 1935, the former king of Iran, Reza Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty, issued a decree asking the international community to use the term Iran, the native name of the country, in formal correspondence. However, the term Persian is still historically used to designate the predominant population of the Iranian peoples living in the Iranian cultural continent.[34][35][36][37]

History

The earliest known written record attributed to the Persians is from the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, an Assyrian inscription from the mid-9th century BC,[38][39] found at Nimrud. The inscription mentions Parsua (presumed to mean "border" or "borderland")[40] as a tribal chiefdom (860–600 BC) in modern-day western Iran.[41][42]

The ancient Persians were a nomadic branch of the Iranian population that, in the early 10th century BC, settled to the northwest of modern-day Iran.[8][9][43][44] They were initially dominated by the Assyrians for much of the first three centuries after arriving in the region. However, they played a major role in the downfall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[45][46] The Medes, another branch of this population, founded the unified empire of Media as the region's dominant cultural and political power in c. 625 BC.[10] Meanwhile, the Persian dynasty of the Achaemenids formed a vassal state to the central Median power. In c. 552 BC, the Achaemenids began a revolution which eventually led to the conquest of the empire by Cyrus II in c. 550 BC. They spread their influence to the rest of what is called the Iranian Plateau, and assimilated with the non-Iranian indigenous groups of the region, including the Elamites and the Mannaeans.[47][48][49]

.svg.png)

At its greatest extent, the Achaemenid Empire stretched from parts of Eastern Europe in the west, to the Indus Valley in the east, making it the largest empire the world had yet seen.[11] The Achaemenids developed the infrastructure to support their growing influence, including the creation of Pasargadae and the opulent city of Persepolis.[50] The empire extended as far as the limits of the Greek city states in modern-day mainland Greece, where the Persians and Athenians influenced each other in what is essentially a reciprocal cultural exchange.[51] Its legacy and impact on the kingdom of Macedon was also notably huge,[13] even for centuries after the withdrawal of the Persians from Europe following the Greco-Persian Wars.[13] The empire collapsed in 330 BC following the conquests of Alexander the Great, but reemerged shortly after as the Parthian Empire.

During the Achaemenid era, Persian colonists settled in Asia Minor.[52] In Lydia (the most important Achaemenid satrapy), near Sardis, there was the Hyrcanian plain, which, according to Strabo, got its name from the Persian settlers that were moved from Hyrcania.[53] Similarly near Sardis, there was the plain of Cyrus, which further signified the presence of numerous Persian settlements in the area.[54] In all these centuries, Lydia and Pontus were reportedly the chief centers for the worship of the Persian gods in Asia Minor.[54] According to Pausanias, as late as the second century AD, one could witness rituals which resembled the Persian fire ceremony at the towns of Hyrocaesareia and Hypaepa.[54] Mithridates III of Cius, a Persian nobleman and part of the Persian ruling elite of the town of Cius, founded the Kingdom of Pontus in his later life, in northern Asia Minor.[55][56] At the peak of its power, under the infamous Mithridates VI the Great, the Kingdom of Pontus also controlled Colchis, Cappadocia, Bithynia, the Greek colonies of the Tauric Chersonesos, and for a brief time the Roman province of Asia. After a long struggle with Rome in the Mithridatic Wars, Pontus was defeated; part of it was incorporated into the Roman Republic as the province Bithynia and Pontus, and the eastern half survived as a client kingdom.

Following the Macedonian conquests, the Persian colonists in Cappadocia and the rest of Asia Minor were cut off from their co-religionists in Iran proper, but they continued to practice the Zoroastrian faith of their forefathers.[57] Strabo, who observed them in the Cappadocian Kingdom in the first century BC, records (XV.3.15) that these "fire kindlers" possessed many "holy places of the Persian Gods", as well as fire temples.[57] Strabo, who wrote during the time of Augustus (r. 63 BC-14 AD), almost three hundred years after the fall of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, records only traces of Persians in western Asia Minor; however, he considered Cappadocia "almost a living part of Persia".[58]

Until the Parthian era, the Iranian identity had an ethnic, linguistic, and religious value. However, it did not yet have a political import.[59] Parthian, a mutually intelligible language with Middle Persian,[60] became an official language of the Parthian Empire. It had influences on Persian,[61][62][63] as well as a major influence on the neighboring Armenian language.

By the time of the Sassanian Empire, a national culture which was fully aware of being Iranian took shape, partially motivated by restoration and revival of the wisdom of "the old sages" (Middle Persian: dānāgān pēšēnīgān).[59] Other aspects of this national culture included the glorification of a great heroic past and an archaizing spirit.[59] Throughout the period, the Iranian identity reached its height in every aspect.[59] Middle Persian, which is the immediate ancestor of Modern Persian and a variety of other Iranian dialects,[61][64][65] became the official language of the empire[66] and was greatly diffused among Iranians.[59]

The Parthians and the Sasanians would also extensively interact with the Romans culturally. The Roman–Persian wars and the Byzantine–Sasanian wars would shape the landscape of Western Asia, Europe, the Caucasus, North Africa, and the Mediterranean Basin for centuries. For a period of over 400 years, the neighboring Byzantines and Sasanians were recognized as the two leading powers in the world.[67][68][69]

The intermingling of Persians, Medes, Parthians, Bactrians, and indigenous "pre-Iranian" people of Iran (including the Elamites) gained more ground, and a homogeneous Iranian identity was created to the extent that all were just called Iranians, irrespective of clannish affiliations and regional linguistic or dialectal alterities. Furthermore, the process of incomers' assimilation which had been started with the Greeks, continued in the face of Arab, Mongol, and Turkic invasions and proceeded right up to Islamic times.[47][70]

Anthropology

In modern-day Iran, Persians make up the majority of the population.[3] They speak the western varieties of modern Persian,[71] which also serves as the country's official language.[72]

Persian language

The Persian language and its various varieties are part of the western group of the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. Modern Persian is classified as a continuation of Middle Persian, the official religious and literary language of the Sasanian Empire, itself a continuation of Old Persian, which was spoken by the time of the Achaemenid Empire.[73][74][75]

Old Persian is one of the oldest Indo-European languages attested in original texts.[76] Examples of Old Persian have been found in present-day Iran, Armenia, Romania (Gherla),[77][78] Iraq, Turkey, and Egypt.[79][80] The oldest attested text written in Old Persian is from the Behistun Inscription.[81]

Related groups

There are several ethnic groups and communities which are either ethnically or linguistically related to the Persian people, living predominantly in Iran, and also within Afghanistan, the Caucasus, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkey, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and the United Arab Emirates.[82]

The Lurish people, living primarily in the western regions of Iran, are an ethnic Iranian people often associated with Persians and Kurds.[83] They speak various dialects of the Lurish language, which are closely related to the Middle Persian language.[84][85]

Concentrated in Azerbaijan, Armenia and Russia (Dagestan), the Caucasian Tat people are another ethnic Iranian people whose mother tongue—the Tat language—is considered a variant of the Persian language. Their origin is traced to the merchants who settled in the region by the time of the Sasanian Empire.[86]

The Hazaras, making up the third largest ethnic group in Afghanistan,[87][88][89] are a Persian-speaking people speaking a variety of Persian called Hazaragi,[90][91] which is more precisely a part of the Dari dialect continuum (one of the two main languages of Afghanistan),[92] and is mutually intelligible with Dari.[93]

The Aimaqs are a semi-nomadic Persian-speaking people found mostly in western Afghanistan.[94] They mainly speak a variety of Persian called Aimaq, which is close to the Khorasani and Dari varieties.[95]

Culture

From the early inhabitants of Persis, to the Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sasanian empires, to the neighboring Greek city states,[96] the kingdom of Macedon,[13] the caliphates and the Islamic world,[97][16] all the way to modern-day Iran and Western Europe, and such far places as those found in India,[98] Asia,[17] and Indonesia, Persian culture has been either recognized, incorporated, adopted, or celebrated.[97][99] This is due mainly to geopolitical conditions, and its intricate relationship with the ever-changing political arena once as dominant as the Achaemenid Empire.

Art

The artistic heritage of the Persians is eclectic, and includes major contributions from both the east and the west. Persian art borrowed heavily from the indigenous Elamite civilization and Mesopotamia, and later from the Hellenistic civilization. In addition, due to the central location of Greater Iran, it has served as a fusion point between eastern and western traditions.

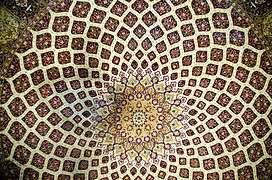

Persians have contributed in various forms of art, including carpet-waving, calligraphy, miniature-painting, illustrated manuscripts, glasswork, lacquer-work, khatam (a native form of marquetry), metalwork, pottery, mosaic, and textile design.[15]

- Ancient Iranian goddess Anahita depicted on a Sasanian silver vessel. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland.

Literature

The Persian language is known to have one of the world's oldest literatures,[18] with prominent medieval poets such as Ferdowsi (author of Šāhnāme, Greater Iran's national epic), Rudaki, Rumi, Hafez Shirazi, Saadi Shirazi, Nizami Ganjavi, Omar Khayyam, and Attar of Nishapur.

Not all Persian literature is written in Persian, as some consider works written by Persians in other languages—such as Arabic and Greek—to be included. At the same time, not all literature written in Persian is written by ethnic Persians or Iranians, as Turkic, Caucasian, and Indic poets and writers have also used the Persian language in the environment of Persianate cultures.

Prominent writers such as Sadegh Hedayat, Forough Farrokhzad, Ahmad Shamlou, Simin Daneshvar, Mehdi Akhavan-Sales and Parvin E'tesami have also had major contributions to contemporary Persian literature.

Architecture

The most prominent examples of ancient Persian architecture are the work of the Achaemenids hailing from Persis. The quintessential feature of Achaemenid architecture was its eclectic nature, with elements from Median architecture, Assyrian architecture, and Asiatic Greek architecture all incorporated.[100] Achaemenid architectural heritage, beginning with the expansion of the empire around 550 BC, was a period of artistic growth that left a legacy ranging from Cyrus the Great's solemn tomb at Pasargadae to the structures at Persepolis, and such historical sites as Naqsh-e Rustam.[101]

During the Sasanian era, multiple architectural projects took place, some of which are still existing, including the Palace of Ardeshir, the Sarvestan Palace, the castle fortifications in Derbent (located in North Caucasus, now part of Russia), and the reliefs at Taq Bostan. The Bam Citadel, a massive structure at 1,940,000 square feet (180,000 m2) constructed on the Silk Road in Bam, is from around the 5th century BC.[102]

Ruins of the Tachara, Persepolis.

Ruins of the Tachara, Persepolis. The Tomb of Cyrus, Pasargadae.

The Tomb of Cyrus, Pasargadae. The Sasanian reliefs at Taq Bostan.

The Sasanian reliefs at Taq Bostan.

Modern contemporary architectural projects influenced by the ancient Achaemenid architecture include the Tomb of Ferdowsi erected under the reign of Reza Shah in Tus, the Azadi Tower erected in 1971 at a square in Tehran, and the Dariush Grand Hotel located on Kish Island in the Persian Gulf.

Gardens

Xenophon, in his Oeconomicus,[103] states:

"The Great King [Cyrus II]...in all the districts he resides in and visits, takes care that there are paradeisos ("paradise", from Avestan pairidaēza) as they [Persians] call them, full of the good and beautiful things that the soil produce."

For the Achaemenid monarchs, gardens assumed an important place.[103] Persian gardens utilized the Achaemenid knowledge of water technologies,[104] as they utilized aqueducts, earliest recorded gravity-fed water rills, and basins arranged in a geometric system. The enclosure of this symmetrically arranged planting and irrigation, by an infrastructure such as a building or a palace created the impression of "paradise".[105] Parthians and Sasanians later added their own modifications to the original Achaemenid design.[103] Later on, the quadripartite design (čārbāq) of Persian gardens was reinterpreted within the Muslim world.

Today, examples of these traditional gardens can be seen in such places as the Tomb of Hafez, Golshan Garden, Qavam House, Eram Garden, Shazdeh Garden, Fin Garden, Tabatabaei House, and the Borujerdis House.

Music

According to the accounts reported by Xenophon, a great number of singers were present at the Achaemenid court. However, little information is available from the music of that era. The music scene of the Sasanian Empire has a more available and detailed documentation than the earlier periods, and is especially more evident within the context of Zoroastrian musical rituals.[106] In general, Sasanian music was influential, and was later adopted in the subsequent eras.[107]

Iranian music, as a whole, utilizes a variety of musical instruments that are unique to the region, and has remarkably evolved since the ancient and medieval times. In traditional Sasanian music, the octave was divided into seventeen tones. By the end of the 13th century, Iranian music also maintained a twelve interval octave, which resembled the western counterparts.[108]

Traditional instruments used in Iranian music include the bowed spike-fiddle kamanche, the goblet drum tonbak, the end-blown flute ney, the large frame drum daf, the hammered dulcimer santur, and the four long-necked lutes tar, dotar, setar, and tanbur. The European string instrument violin is also used, with an alternative tuning preferred by Iranian musicians.

Carpets

Carpet weaving is an essential part of the Persian culture,[109] and Persian rugs are said to be one of the most detailed hand-made works of art.

Achaemenid rug and carpet artistry is well recognized. Xenophon describes the carpet production in the city of Sardis, stating that the locals take pride in their carpet production. A special mention of Persian carpets is also made by Athenaeus of Naucratis in his Deipnosophistae, as he describes a "delightfully embroidered" Persian carpet with "preposterous shapes of griffins".[110]

The Pazyryk carpet—a Scythian pile-carpet dating back to the 4th century BC, which is regarded the world's oldest existing carpet—depicts elements of Assyrian and Achaemenid design, including stylistic references to the stone slab designs found in Persian royal buildings.[110]

A Persian carpet kept at the Louvre.

A Persian carpet kept at the Louvre. Detail of a Persian carpet.

Detail of a Persian carpet. An Isfahan rug.

An Isfahan rug.

Observances

One of the most renowned traditions observed by the Persians is the festival of Nowruz. Considered the national New Year of the Iranian peoples, the festival of Nowruz has its roots in ancient Iranian traditions, and has been recognized within UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.[111]

Other traditional celebrations such as Charshanbe Suri, Sizde be Dar, and the Night of Yalda are also widely observed by the Persian people.

References

- ↑ United States Central Intelligence Agency(CIA) (April 28, 2011). "The World Fact Book – Iran". CIA. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- 1 2 Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. "Ethnic Groups and Languages of Iran" (PDF). Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- 1 2 "The World Factbook - Iran". Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Beck, Lois (2014). Nomads in Postrevolutionary Iran: The Qashqa'i in an Era of Change. Routledge. p. xxii. ISBN 978-1317743866.

(...) an ethnic Persian; adheres to cultural systems connected with other ethnic Persians

- ↑ Samadi, Habibeh; Nick Perkins (2012). Martin Ball; David Crystal; Paul Fletcher, eds. Assessing Grammar: The Languages of Lars. Multilingual Matters. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-84769-637-3.

- ↑ Fyre, R. N. (March 29, 2012). "IRAN v. PEOPLES OF IRAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

The largest group of people in present-day Iran are Persians (*q.v.) who speak dialects of the language called Fārsi in Persian, since it was primarily the tongue of the people of Fārs.

- ↑ Coon, C.S. "Demography and Ethnography". Iran. Encyclopaedia of Islam. IV. E.J. Brill. pp. 10–8.

The Lurs speak an aberrant form of Archaic Persian (...)

- 1 2 "Persian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- 1 2 David Sacks; Oswyn Murray; Lisa R. Brody (2005). Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world. Infobase Publishing. p. 256 (at the right portion of the page).

- 1 2 "Media". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- 1 2 Sacks, David; Murray, Oswyn; Brody, Lisa R. (2005). Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World. Facts On File. p. 256 (at the right portion of the page). ISBN 978-0-8160-5722-1.

- ↑ Farr, Edward (1850). History of the Persians. Robert Carter. pp. 124–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Roisman & Worthington 2011, p. 345.

- ↑ Durant, Will (1950). Age of Faith. Simon and Schuster. p. 150.

Repaying its debt, Sasanian art exported it forms and motives eastward into India, Turkestan, and China, westward into Syria, Asia Minor, Constantinople, the Balkans, Egypt, and Spain.

- 1 2 Burke, Andrew; Elliot, Mark (2008). Iran. Lonely Planet. pp. 295 & 114–5 (for architecture) and pp. 68–72 (for arts).

- 1 2 Hovannisian, Richard G.; Sabagh, Georges (1998). The Persian Presence in the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–83.

- 1 2 Spuler, Bertold; Marcinkowski, M. Ismail (2003). Persian Historiography & Geography. Pustaka Nasional Pte Ltd.

- 1 2 Arberry, Arthur John (1953). The Legacy of Persia. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-19-821905-9.

- 1 2 "TAJIK i. THE ETHNONYM: ORIGINS AND APPLICATION". Encyclopædia Iranica. July 20, 2009.

By mid-Safavid times the usage tājik for 'Persian(s) of Iran' may be considered a literary affectation, an expression of the traditional rivalry between Men of the Sword and Men of the Pen. Pietro della Valle, writing from Isfahan in 1617, cites only Pārsi and ʿAjami as autonyms for the indigenous Persians, and Tāt and raʿiat 'peasant(ry), subject(s)' as pejorative heteronyms used by the Qezelbāš (Qizilbāš) Torkmān elite. Perhaps by about 1400, reference to actual Tajiks was directed mostly at Persian-speakers in Afghanistan and Central Asia; (...)

- ↑ Ostler, Nicholas (2010). The Last Lingua Franca: English Until the Return of Babel. Penguin UK. pp. 1–352. ISBN 978-0141922218.

Tat was known to have been used at different times to designate Crimean Goths, Greeks and sedentary peoples generally, but its primary reference came to be the Persians within the Turkic domains. (...) Tat is nowadays specialized to refer to special groups with Iranian languages in the west of the Caspian Sea.

- ↑ Nava'i, Ali Shir (tr. & ed. Robert Devereaux) (1996). Muhakamat al-lughatain. Leiden: Brill. p. 6.

- ↑ Starr, S. F. (2013). Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Περσίς. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Persia". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Herodotus. "61". Histories. Book 7.

- ↑ Herodotus. "150". Histories. Book 7.

- ↑ Wilson, Arnold. "The Middle Ages: Fars". The Persian Gulf (RLE Iran A). p. 71.

- 1 2 Axworthy, Michael. Iran: What Everyone Needs to Know. p. 16.

- ↑ For example, Abu Rayhan Biruni, a native speaker of the Eastern Iranian language Khwarezmian mentions in his Āthār al-bāqiyah ʻan al-qurūn al-xāliyah that "the people of Khwarizm, they are a branch of the Persian tree." See Abu Rahyan Biruni, "Athar al-Baqqiya 'an al-Qurun al-Xaliyyah" ("Vestiges of the past: chronology of ancient nations"), Tehran, Miras-e-Maktub, 2001. Original Arabic of the quote: "و أما أهل خوارزم، و إن کانوا غصنا ً من دوحة الفُرس"(pg 56)

- ↑ The language used in the ancient Marzbānnāma was, in the words of the 13th-century historian Sa'ad ad-Din Warawini, "the language of Ṭabaristan and old, original Persian (fārsī-yi ḳadīm-i bāstān)" See Kramers, J.H. "Marzban-nāma." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Ed: P. Bearman, Th. Bianqui,, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007. Brill Online. November 18, 2007 <http://www.brillonline.nl/subscriber/entry?entry=islam_SIM-4990>

- ↑ The language of Tabriz, being an Iranian language during the time of Qatran Tabrizi, was not the standard Khurasani Parsi-ye Dari. Qatran Tabrizi(11th century) has an interesting couplet mentioning this fact: Mohammad-Amin Riahi. “Molehaazi darbaareyeh Zabaan-I Kohan Azerbaijan”(Some comments on the ancient language of Azerbaijan), ‘Itilia’at Siyasi Magazine, volume 181–182.

- ↑ Al Mas'udi (1894). De Goeje, M.J., ed. Kitab al-Tanbih wa-l-Ishraf (in Arabic). Brill. pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Ibn Battuta (2004). Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354. Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 0-415-34473-5.

We travelled on to Kabul, formerly a vast town, the site of which is now occupied by a village inhabited by a tribe of Persians called Afghans. They hold mountains and defiles and possess considerable strength, and are mostly highwaymen. Their principal mountain is called Kuh Sulayman. It is told that the prophet Sulayman [Solomon] ascended this mountain and having looked out over India, which was then covered with darkness, returned without entering it.

- ↑ "Iran". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Persian entry in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. August 13, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition (2000). "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ↑ Bausani, Alessandro. The Persians, from the earliest days to the twentieth century. 1971, Elek. ISBN 978-0-236-17760-8

- ↑ Abdolhossein Zarinkoob "Ruzgaran : tarikh-e Iran az aghaz ta soqut-e saltnat-e Pahlevi" pp. 37

- ↑ Bahman Firuzmandi "Mad, Hakhamaneshi, Ashkani, Sasani" pp. 155

- ↑ Gershevitch,, Ilya; Bayne Fisher, William; A. Boyle, J. (1985). The Cambridge History of Iran. II (reissue, illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780521200912.

- ↑ Eduljee, K D. "Zoroastrian Heritage The Zagros". 2012. The Heritage Site. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ↑ Gershevitch,, Ilya; Bayne Fisher, William; A. Boyle, J. (1985). The Cambridge History of Iran. II (reissue, illustrated, reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 9780521200912.

- ↑ Stearns, Peter N (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6 ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/ Bartleby.com.

The Medes and the Persians, c.1500-559

- ↑ Bahman Firuzmandi "Mad, Hakhamanishi, Ashkani, Sasani" pp. 20

- ↑ Grant, R G. Battle a Visual Journey Through 5000 Years of Combat. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2005 pg 19.

- ↑ F Leo Oppenheim – Ancient Mesopotamia

- 1 2 Lands of Iran Archived 2009-02-15 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia Iranica (July 25, 2005) (retrieved March3, 2008)

- ↑ Iran. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05 Archived 2009-03-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Bahman Firuzmandi "Mad, Hakhamanishi, Ashkani, Sasani" pp. 12–19

- ↑ Gates, Charles (2003). Ancient cities: the archaeology of urban life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Psychology Press. p. 186.

- ↑ Margaret Christina Miller (2004). Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge University Press. p. 243.

- ↑ Raditsa 1983, p. 105.

- ↑ Raditsa 1983, pp. 102, 105.

- 1 2 3 Raditsa 1983, p. 102.

- ↑ McGing 1986, p. 15.

- ↑ Van Dam 2002, p. 17.

- 1 2 Boyce 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Raditsa 1983, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 GHERARDO GNOLI, "IRANIAN IDENTITY" in Encyclopaedia Iranica". Excerpt 1: " All this evidence shows that the name arya Iranian was a collective definition, denoting peoples (Geiger, pp. 167 f.; Schmitt, 1978, p. 31) who were aware of belonging to the one ethnic stock, speaking a common language, and having a religious tradition that centered on the cult of Ahura Mazdā.". Excerpt 2: "The inscriptions of Darius I (see DARIUS iii) and Xerxes, in which the different provinces of the empire are listed, make it clear that, between the end of the 6th century and the middle of the 5th century B.C.E., the Persians were already aware of belonging to the ariya “Iranian” nation (see ARYA and ARYANS). Darius and Xerxes boast of belonging to a stock which they call “Iranian”: they proclaim themselves “Iranian” and “of Iranian stock,” ariya and ariya čiça respectively, in inscriptions in which the Iranian countries come first in a list that is arranged in a new hierarchical and ethno-geographical order, compared for instance with the list of countries in Darius’s inscription at Behistun" Excerpt 3: "Although, up until the end of the Parthian period, Iranian identity had an ethnic, linguistic, and religious value, it did not yet have a political import. The idea of an “Iranian” empire or kingdom is a purely Sasanian one". Excerpt 4:"It was in the Sasanian period, then, that the pre-Islamic Iranian identity reached the height of its fulfilment in every aspect: political, religious, cultural, and linguistic (with the growing diffusion of Middle Persian). Its main ingredients were the appeal to a heroic past that was identified or confused with little-known Achaemenid origins (Yarshater, 1971; Daryaee, 1995), and the religious tradition, for which the Avesta was the chief source.". Also accessed online at: in May, 2011

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica: ""Middle Persian [Sassanian Pahlava] and Parthian were doubtlessly similar enough to be mutually intelligible." (Enc.Brit.vol.22,2003, p.627)

- 1 2 Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier, Peter Trudgill, "Sociolinguistics Hsk 3/3 Series Volume 3 of Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society", Walter de Gruyter, 2006. 2nd edition. pg 1912. Excerpt: "Middle Persian, also called Pahlavi is a direct continuation of old Persian, and was used as the written official language of the country." "However, after the Moslem conquest and the collapse of the Sassanids, Arabic became the dominant language of the country and Pahlavi lost its importance, and was gradually replaced by Dari, a variety of Middle Persian, with considerable loan elements from Arabic and Parthian."

- ↑ Windfuhr, G. (1989), “New West Iranian,” R. Schmitt (ed.), Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum, Wiesbaden: 251-62.

- ↑ Asatrian, G. (1995), “Dimli”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition.

- ↑ Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2006). Encyclopedia Iranica,"Iran, vi. Iranian languages and scripts, "new Persian, is "the descendant of Middle Persian" and has been "official language of Iranian states for centuries", whereas for other non-Persian Iranian languages "close genetic relationships are difficult to establish" between their different (Middle and Modern) stages. Modern Yaḡnōbi belongs to the same dialect group as Sogdian, but is not a direct descendant; Bactrian may be closely related to modern Yidḡa and Munji (Munjāni); and Wakhi (Wāḵi) belongs with Khotanese."

- ↑ Gilbert Lazard: The language known as New Persian, which usually is called at this period (early Islamic times) by the name of Dari or Farsi-Dari, can be classified linguistically as a continuation of Middle Persian, the official religious and literary language of Sassanian Iran, itself a continuation of Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenids. Unlike the other languages and dialects, ancient and modern, of the Iranian group such as Avestan, Parthian, Soghdian, Kurdish, Balochi, Pashto, etc., Old Middle and New Persian represent one and the same language at three states of its history. It had its origin in Fars (the true Persian country from the historical point of view) and is differentiated by dialectical features, still easily recognizable from the dialect prevailing in north-western and eastern Iran. In Lazard, Gilbert 1975, "The Rise of the New Persian Language" in Frye, R. N., The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 4, pp. 595–632, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Benjamin W. Fortson, "Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction", John Wiley and Sons, 2009. pg 242: " Middle Persian was the official language of the Sassanian dynasty"

- ↑ (Shapur Shahbazi 2005)

- ↑ Norman A. Stillman The Jews of Arab Lands pp 22 Jewish Publication Society, 1979 ISBN 0827611552

- ↑ International Congress of Byzantine Studies Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Byzantine Studies, London, 21–26 August 2006, Volumes 1–3 pp 29. Ashgate Pub Co, September 30, 2006 ISBN 075465740X

- ↑ "History of Iran". Iranologie.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ↑ "Subfamily: Farsic", Glottolog

- ↑ "Iran". University of Cambridge. Archived from the original on September 18, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ↑ Lazard, Gilbert 1975, "The Rise of the New Persian Language" in Frye, R. N., The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 4, pp. 595–632, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. "The language known as New Persian, which usually is called at this period (early Islamic times) by the name of Dari or Farsi-Dari, can be classified linguistically as a continuation of Middle Persian, the official religious and literary language of Sassanian Iran, itself a continuation of Old Persian, the language of the Achaemenids. Unlike the other languages and dialects, ancient and modern, of the Iranian group such as Avestan, Parthian, Soghdian, Kurdish, Balochi, Pashto, etc., Old Persian, Middle and New Persian represent one and the same language at three states of its history. It had its origin in Fars (the true Persian country from the historical point of view) and is differentiated by dialectical features, still easily recognizable from the dialect prevailing in north-western and eastern Iran."

- ↑ Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier, Peter Trudgill, "Sociolinguistics Hsk 3/3 Series Volume 3 of Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society", Walter de Gruyter, 2006. 2nd edition. pg 1912. Excerpt: "Middle Persian, also called Pahlavi is a direct continuation of old Persian, and was used as the written official language of the country." "However, after the Moslem conquest and the collapse of the Sassanids, the Pahlavi language was gradually replaced by Dari, a variety of Middle Persian, with considerable loan elements from Arabic and Parthian."

- ↑ Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2006). Encyclopedia Iranica, "Iran, vi. Iranian languages and scripts, "new Persian, is "the descendant of Middle Persian" and has since been "official language of Iranian states for centuries", whereas for other non-Persian Iranian languages "close genetic relationships are difficult to establish" between their different (Middle and Modern) stages. Modern Yaḡnōbi belongs to the same dialect group as Sogdian, but is not a direct descendant; Bactrian may be closely related to modern Yidḡa and Munji (Munjāni); and Wakhi (Wāḵi) belongs with Khotanese."

- ↑ (Skjærvø 2006, vi(2). Documentation. Old Persian.)

- ↑ Kuhrt 2013, p. 197.

- ↑ Schmitt 2000, p. 53.

- ↑ Roland G. Kent, Old Persian, 1953

- ↑ Kent, R. G.: "Old Persian: Grammar Texts Lexicon", page 6. American Oriental Society, 1950.

- ↑ (Schmitt 2008, pp. 80–1)

- ↑ "SociolinguistEssex X – 2005" (PDF). Essex University. 2005. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-14. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- ↑ Frye, Richard N. (1983). Handbuch der Altertumswissenschaft, Part 3, Volume 7. Beck. p. 29. ISBN 978-3406093975.

- ↑ Don Stillo, "Isfahan-Provincial Dialects" in Encyclopedia Iranica, Excerpt: "While the modern SWI languages, for instance, Persian, Lori-Bak_tia-ri and others, are derived directly from Old Persian through Middle Persian/Pahlavi"

- ↑ C.S. Coon, "Iran:Demography and Ethnography" in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume IV, E.J. Brill, pp 10,8.

- ↑ Vladimir Minorsky (1958). A history of Sharvan and Darband in the 10th - 11th centuries. Heffer.

- ↑ "Afghanistan: 31,822,848 (July 2014 est.) @ 9% (2014)". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ↑ Kamal Hyder reports (12 Nov 2011). "Hazara community finds safe haven in Peshawar". Aljazeer English. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Ethnic Groups of Afghanistan". Library of Congress Country Studies on Afghanistan. 1997. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ "HAZĀRA iv. Hazāragi dialect". Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ "Attitudes towards Hazaragi". Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ Schurmann, Franz (1962) The Mongols of Afghanistan: An Ethnography of the Moghôls and Related Peoples of Afghanistan Mouton, The Hague, Netherlands, page 17, OCLC 401634

- ↑ "Attitudes Towards Hazaragi". Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ↑ Janata, A. "AYMĀQ". In Ehsan Yarshater. Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). United States: Columbia University.

- ↑ "Aimaq". World Culture Encyclopedia. everyculture.com. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ Grote (1899). Greece: I. Legendary Greece: II. Grecian history to the reign of Peisistratus at Athens. 12. P. F. Collier. p. 106.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - 1 2 Lapidus, Ira Marvin (2002). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 127.

- ↑ Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 17.

- ↑ Miller, Margaret Christina (2004). Athens and Persia in the Fifth Century BC: A Study in Cultural Receptivity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 243–251.

- ↑ Charles Henry Caffin (1917). How to study architecture. Dodd, Mead and Company. p. 80.

- ↑ Marco Bussagli (2005). Understanding Architecture. I.B.Tauris. p. 211.

- ↑ Rafie Hamidpour D E Dabfe, Rafie Hamidpour (2010). Land of Lion, Land of Sun. AuthorHouse. p. 54.

- 1 2 3 Penelope Hobhouse; Erica Hunningher; Jerry Harpur (2004). Gardens of Persia. Kales Press. pp. 7–13.

- ↑ L. Mays (2010). Ancient Water Technologies. Springer. pp. 95–100.

- ↑ Mehdi Khansari; M. Reza Moghtader; Minouch Yavari (2004). Persian Garden: Echoes Of Paradise. Mage Publishers.

- ↑ (Lawergren 2009) iv. First millennium C.E. (1) Sasanian music, 224-651.

- ↑ Seyyed Hossein Nasr (1987). Islamic art and spirituality. SUNY Press. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Janet M. Green; Josephine Thrall (1908). The American history and encyclopedia of music. I. Squire. pp. 55–58.

- ↑ Mary Beach Langton (1904). How to know oriental rugs, a handbook. D. Appleton and Company. pp. 57–59.

- 1 2 Ronald W. Ferrier (1989). The Arts of Persia. Yale University Press. pp. 118–120.

- ↑ UNCESCO (2009). "Intangible Heritage List". Retrieved March 9, 2011.

Sources

- Ansari, Ali M. (2014). Iran: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199669349.

- Boyce, Mary (2001). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415239028.

- McGing, B.C. (1986). The Foreign Policy of Mithridates VI Eupator, King of Pontus. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004075917.

- Raditsa, Leo (1983). "Iranians in Asia Minor". In Yarshater, Ehsan. The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3 (1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139054942.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2010). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 1-4051-7936-8.

- Roisman, Joseph; Worthington, Ian (2011). A Companion to Ancient Macedonia. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 1-4443-5163-X.

- Van Dam, Raymond (2002). Kingdom of Snow: Roman Rule and Greek Culture in Cappadocia. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812236811.