Painted Grey Ware culture

.png)

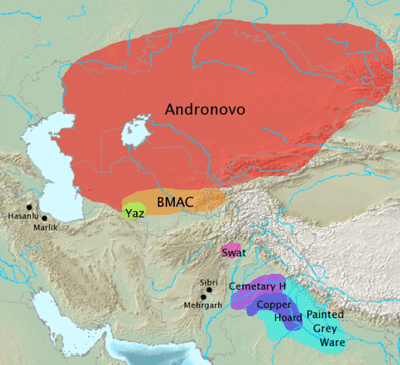

The Painted Grey Ware culture (PGW) is an Iron Age Indian culture of the western Gangetic plain and the Ghaggar-Hakra valley on the Indian subcontinent, lasting from roughly 1200 BCE to 600 BCE.[1][2][3] It is a successor of the Black and red ware culture (BRW) within this region, and contemporary with the continuation of the BRW culture in the eastern Gangetic plain and Central India.[4]

Characterized by a style of fine, grey pottery painted with geometric patterns in black,[5] the PGW culture is associated with village and town settlements, domesticated horses, ivory-working, and the advent of iron metallurgy.[6] Total number of PGW sites discovered so far is more than 1100.[7] Although most PGW sites were small farming villages, "several dozen" PGW sites emerged as relatively large settlements that can be characterized as towns; the largest of these were fortified by ditches or moats and embankments made of piled earth with wooden palisades, albeit smaller and simpler than the elaborate fortifications which emerged in large cities after 600 BCE.[8]

The PGW Culture probably corresponds to the middle and late Vedic period, i.e., the Kuru-Panchala kingdom, the first large state in South Asia after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization.[9][10] It is succeeded by Northern Black Polished Ware from c. 700-500 BCE, associated with the rise of the great mahajanapada states and of the Magadha Empire.

Overview

The PGW culture cultivated rice, wheat, and barley, and domesticated cattle, sheep, pigs, and horses. Houses were built of wattle-and-daub, mud, or bricks, ranging in size from small huts to large houses with many rooms. There is a clear settlement hierarchy, with a few central towns that stand out amongst numerous small villages. Some sites, including Jakhera in Uttar Pradesh, demonstrate a “fairly evolved, proto-urban or semi-urban stage” of this culture, with evidence of social organization and trade, including ornaments of gold, copper, ivory, and semi-precious stones, storage bins for surplus grain, stone weights, paved streets, water channels and embankments.[11]

Arts and crafts of the PGW people are represented by ornaments (made from terracotta, stone, faience, and glass), human and animal figurines (made from terracotta) as well as "incised terracotta discs with decorated edges and geometric motifs" which probably had "ritual meaning," perhaps representing symbols of deities.[12] There are a few stamp seals with geometric designs but no inscription, contrasting with both the prior Harappan seals and the subsequent Brahmi-inscribed seals of the Northern Black Polished Ware culture.[13]

At Bhagwanpura in the Kurukshetra district of Haryana, excavations have revealed an overlap between the late Harappan and Painted Grey Ware cultures, large houses that may have been elite residences, and fired bricks that may have been used in Vedic altars.[14]

Fresh surveys by archaeologist Vinay Kumar Gupta suggest Mathura was the largest PGW site around 375 hectares in area.[15] Among the largest sites is also the recently excavated Ahichatra, with at least 40 hectares of area in PGW times along with evidence of early construction of the fortification which goes back to PGW levels.[16] Two periods of PGW were identified recently at Ahichhatra, the earliest from 1500 to 800 BCE, and the Late from 800 to 400 BCE.[17]

Towards the end of the period, many of the PGW settlements grew into the large towns and cities of the Northern Black Polished Ware period.[18]

Interpretations

In the 1950s, archaeologist B.B. Lal associated Hastinapura, Mathura, Ahichatra, Kampilya, Barnava, Kurukshetra and other sites of PGW culture with the Mahabharata period. Furthermore, he pointed out that the Mahabharata mentions a flood and a layer of flooding debris was found in Hastinapura. However, B.B. Lal considered his theories to be provisional and based upon a limited body of evidence, and he later reconsidered his statements on the nature of this culture (Kenneth Kennedy 1995). B.B. Lal confirms that Mahabharata is associated with PGW sites in a recent 2012 presentation at the International Seminar on Mahabharata held by Draupadi Trust and gives a date to c. 900 BCE for the War recounted in the Mahabharata.[19]

The pottery style of this culture is different from the pottery of the Iranian Plateau and Afghanistan (Bryant 2001). In some sites, PGW pottery and Late Harappan pottery are contemporaneous.[20] The archaeologist Jim Shaffer (1984:84-85) has noted that "at present, the archaeological record indicates no cultural discontinuities separating Painted Grey Ware from the indigenous protohistoric culture." However, the continuity of pottery styles may be explained by the fact that pottery was generally made by indigenous craftsmen even after the Indo-Aryan migration.[21] According to Chakrabarti (1968) and other scholars, the origins of the subsistence patterns (e.g. rice use) and most other characteristics of the Painted Grey Ware culture are in eastern India or even Southeast Asia.[note 1]

In 2013, the University of Cambridge and Banaras Hindu University excavated at Alamgirpur near Delhi, where they found a period overlap between the later part of the Harappan phase (with a "noticeable slow decline in quality") and the earliest PGW levels; Sample OxA-21882 showed a calibrated radiocarbon dating from 2136 BCE to 1948 BCE, but seven other samples from the overlap phase that were submitted for dating failed to give a result.[22] A team of the Archaeological Survey of India led by B.R. Mani and Vinay Kumar Gupta collected charcoal samples from Gosna, a site 6 km east of Mathura across the Yamuna river, where two of the radiocarbon dates from the PGW deposit came out to be 2160 BCE and 2170 BCE, but they mention that "there is a possibility that the cultural horizon which is now regarded as belonging to the P.G.W. period might turn out to be as belonging to a period with only plain grey ware."[23]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2005-09-06.

- ↑ Douglas Q. Adams (January 1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 310–. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ↑ Kailash Chand Jain (1972). Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-81-208-0824-9.

- ↑ Franklin Southworth, Linguistic Archaeology of South Asia (Routledge, 2005), p.177

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=WGUz01yBumEC&pg=PA357

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=tzU3RIV2BWIC&pg=PA414

- ↑ Vikrama, Bhuvan & Daljeet Singh, 2014."Classification of Motifs on Painted Grey Ware", in Pracyabodha, Indian Archaeology and Tradition, Vol.2, Delhi, pp. 223-229

- ↑ James Heitzman, The City in South Asia (Routledge, 2008), pp.12-13

- ↑ Geoffrey Samuel, (2010) The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press, pp. 45–51

- ↑ Michael Witzel (1989), Tracing the Vedic dialects in Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes ed. Caillat, Paris, 97–265.

- ↑ Upinder Singh (2009), A History of Ancient and Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Delhi:Longman, pp. 246–248

- ↑ J.M. Kenoyer (2006), "Cultures and Societies of the Indus Tradition. In Historical Roots" in the Making of ‘the Aryan’, R. Thapar (ed.), pp. 21–49. New Delhi, National Book Trust.

- ↑ Kenoyer (2006)

- ↑ Kenoyer (2006)

- ↑ Vinay Gupta, Early Settlement of Mathura : An Archaeological Perspective, An Occasional paper published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, N. Delhi

- ↑ http://www.educationtimes.com/article/290/20130917201309171524062507304cdb3/What-Lies-Beneath.html

- ↑ http://www.currentscience.ac.in/cs/Volumes/109/07/1293.pdf CURRENT SCIENCE, VOL. 109, NO. 7, 10 OCTOBER 2015, p. 1301

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-01. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ↑ http://es.slideshare.net/sfih108/mahabharata-historicity-prof-b-b-lal

- ↑ Shaffer, Jim. 1993, Reurbanization: The eastern Punjab and beyond. In Urban Form and Meaning in South Asia: The Shaping of Cities from Prehistoric to Precolonial Times, ed. H. Spodek and D.M. Srinivasan.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ Singh, R.N., Cameron Petrie et al. (2013)."Recent Excavations at Alamgirpur, Meerut District: A Preliminary Report" in Man and Environment 38(1), pp. 32-54 https://www.academia.edu/8246061/Received_Recent_Excavations_at_Alamgirpur_Meerut_District_A_Preliminary_Report_Indian_Society_for_Prehistoric_and_Quaternary_Studies

- ↑ Gupta, Vinay Kumar, (2014)."Early Settlement of Mathura: An Archaeological Perspective" in History and Society, New Series 41, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi, pp. 1-37 https://www.academia.edu/7025503/Early_Settlement_of_Mathura_An_Archaeological_Perspective_An_Occasional_paper_published_by_Nehru_Memorial_Museum_and_Library_N._Delhi

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513777-9.

- Chakrabarti, D.K. 1968. The Aryan hypothesis in Indian archaeology. Indian Studies Past and Present 4, 333-358.

- Jim Shaffer. 1984. The Indo-Aryan Invasions: Cultural Myth and Archaeological Reality. In: J.R. Lukak. The People of South Asia. New York: Plenum. 1984.

- Kennedy, Kenneth 1995. “Have Aryans been identified in the prehistoric skeletal record from South Asia?”, in George Erdosy, ed.: The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia, p. 49-54.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Painted Grey Ware. |