Haplogroup N (mtDNA)

| Haplogroup N | |

|---|---|

| |

| Possible time of origin | ~71,000 YBP[1][1] |

| Possible place of origin | Asia[2][3][4][5][6] or East Africa[7][8] |

| Ancestor | L3 |

| Descendants | N1'5, N2, N8, N9, N10, N11, N13, N14, N21, N22, A, I, O, R, S, X, Y, W |

| Defining mutations | 8701, 9540, 10398, 10873, 15301[9] |

Haplogroup N is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) clade. A macrohaplogroup, its descendant lineages are distributed across many continents. Like its sibling macrohaplogroup M, macrohaplogroup N is a descendant of the haplogroup L3.

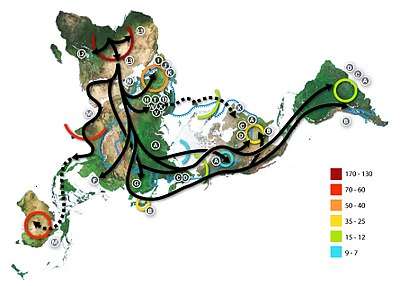

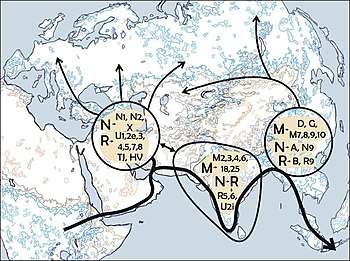

All mtDNA haplogroups found outside of Africa are descendants of either haplogroup N or its sibling haplogroup M. M and N are the signature maternal haplogroups that define the theory of the recent African origin of modern humans and subsequent early human migrations around the world. The global distribution of haplogroups N and M indicates that there was likely at least one major prehistoric migration of humans out of Africa, with both N and M later evolving outside the continent.[5]

Origins

There is widespread agreement in the scientific community concerning the African ancestry of haplogroup L3 (haplogroup N's parent clade).[10] However, whether or not the mutations which define haplogroup N itself first occurred within Asia or Africa has been a subject for ongoing discussion and study.[10]

The out of Africa hypothesis has gained generalized consensus. However, many specific questions remain unsettled. To know whether the two M and N macrohaplogroups that colonized Eurasia were already present in Africa before the exit is puzzling.

Torroni et al. 2006 state that Haplogroups M, N and R occurred somewhere between East Africa and the Persian Gulf.[11]

Also related to the origins of haplogroup N is whether ancestral haplogroups M, N and R were part of the same migration out of Africa, or whether Haplogroup N left Africa via the Northern route through the Levant, and M left Africa via Horn of Africa. This theory was suggested because haplogroup N is by far the predominant haplogroup in Western Eurasia, and haplogroup M is absent in Western Eurasia, but is predominant in India and is common in regions East of India. However, the mitochondrial DNA variation in isolated "relict" populations in southeast Asia and among Indigenous Australians supports the view that there was only a single dispersal from Africa. Southeast Asian populations and Indigenous Australians all possess deep rooted clades of both haplogroups M and N.[12] The distribution of the earliest branches within haplogroups M, N, and R across Eurasia and Oceania therefore supports a three-founder-mtDNA scenario and a single migration route out of Africa.[13] These findings also highlight the importance of Indian subcontinent in the early genetic history of human settlement and expansion.[14]

Asian origin hypothesis

The hypothesis of Asia as the place of origin of haplogroup N is supported by the following:

- Haplogroup N is found in all parts of the world but has low frequencies in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to a number of studies, the presence of Haplogroup N in Africa is most likely the result of back migration from Eurasia.[4]

- The oldest clades of macrohaplogroup N are found in Asia and Australia.

- It would be paradoxical that haplogroup N had traveled all the distance to Australia or New World yet failed to affect other populations within Africa besides North Africans and Horn Africans.

- N1 is the only sub-clade of haplogroup N that has been observed in Africa. However N1a is the only one in East Africa: this haplogroup is even younger and is not restricted to Africa, N1a has also been detected in Southern Siberia and was found in a 2,500-year-old Scytho-Siberian burial in the Altai region.[15]

- The mitochondrial DNA variation in isolated "relict" populations in southeast Asia supports the view that there was only a single dispersal from Africa.[12] The distribution of the earliest branches within haplogroups M, N, and R across Eurasia and Oceania provides additional evidence for a three-founder-mtDNA scenario and a single migration route out of Africa.[13] These findings also highlight the importance of Indian subcontinent in the early genetic history of human settlement and expansion.[14] Therefore, N’s history is similar to M and R which have their most probably origin in South Asia.

African origin hypothesis

According to Toomas Kivisild "the lack of L3 lineages other than M and N in India and among non-African mitochondria in general suggests that the earliest migration(s) of modern humans already carried these two mtDNA ancestors, via a departure route over the Horn of Africa.[7]

Distribution

Haplogroup N is derived from the ancestral L3 macrohaplogroup, which represents the migration discussed in the theory of the recent African origin of modern humans. Haplogroup N is the ancestral haplogroup to almost all clades today distributed in Europe and Oceania, as well as many found in Asia and the Americas. It is believed to have arisen at a similar time to haplogroup M. Haplogroup N subclades like haplogroup U6 are also found at high to low frequencies in northwest and northeast Africa due to a back migration from Europe or Asia during the Paleolithic ca. 46,000 ybp, the estimated age of the basal U6* clade.[16]

The haplogroup N descendant lineage U6 has been found among Iberomaurusian specimens at the Taforalt site, which date from the Epipaleolithic.[17] The N1b subclade has been observed in an individual belonging to the Mesolithic Natufian culture.[18] Additionally, haplogroup N has been found among ancient Egyptian mummies excavated at the Abusir el-Meleq archaeological site in Middle Egypt, which date from the Pre-Ptolemaic/late New Kingdom, Ptolemaic, and Roman periods.[19]

The N1 subclade has also been found in various fossils that were analysed for ancient DNA, including specimens associated with the Starčevo (N1a1a1, Alsónyék-Bátaszék, Mérnöki telep, 1/3 or 33%), Linearbandkeramik (N1a1a1a3, Szemely-Hegyes, 1/1 or 100%; N1a1b/N1a1a3/N1a1a1a2/N1a1a1/N1a1a1a, Halberstadt-Sonntagsfeld, 6/22 or ~27%), Alföld Linear Pottery (N1a1a1, Hejőkürt-Lidl, 1/2 or 50%), Transdanubian Late Neolithic (N1a1a1a, Apc-Berekalja, 1/1 or 100%), Protoboleráz (N1a1a1a3, Abony, Turjányos-dűlő, 1/4 or 25%), and Iberia Early Neolithic cultures (N1a1a1, Els Trocs, 1/4 or 25%).[20]

In popular science

In the book The Real Eve, Stephen Oppenheimer refers to haplogroup N as "Nasreen" as haplogroup N may have arisen near the Persian Gulf. In his popular book The Seven Daughters of Eve, Bryan Sykes named the originator of this mtDNA haplogroup "Naomi".

Subgroups distribution

Haplogroup N's derived clades include the macro-haplogroup R and its descendants, and haplogroups A, I, S, W, X, and Y.

The rare basal haplogroup N* has been found among fossils belonging to the Cardial and Epicardial culture (Cardium pottery) and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B.[21]

Basal N* now occurs at its highest frequencies among the Soqotri (24.3%).[22]

Undifferentiated haplogroup N is especially common in the Horn of Africa, constituting around 20% of maternal lineages among Somalis.[23] It is also found at low frequencies among Algerians and Reguibate Sahrawi.[24]

- Haplogroup N1'5

- Haplogroup N2

- Haplogroup N2a – small clade found in West Europe.[29]

- Haplogroup W[30] – found in Western Eurasia and South Asia[31]

- Haplogroup N8 – found in China.[32]

- Haplogroup N9 – found in Far East.[25]

- Haplogroup N9a – East Asia, Southeast Asia and Central Asia.

- Haplogroup N9b – found in Japan and the lower basin of the Amur River.

- Haplogroup Y[33] – found especially among Nivkhs, Ulchs, Negidals, Ainus, and the population of Nias Island, with a moderate frequency among other Tungusic peoples, Koreans, Mongols, Koryaks, Itelmens, Chinese, Japanese, Tajiks, Island Southeast Asians (including Taiwanese aborigines), and some Turkic peoples[15]

- Haplogroup N10 – found in China and Southeast Asia.[32]

- Haplogroup N11 – found in China and the Philippines.[34]

- Haplogroup O or N12- found among indigenous Australians and the Floresians of Indonesia.

- Haplogroup N13 – indigenous Australians[35]

- Haplogroup N14 – indigenous Australians[36]

- Haplogroup N21 – In ethnic Malays from Malaysia and Indonesia.[37]

- Haplogroup N22 – Southeast Asia and Japan[38]

- Haplogroup A[39] – found in Central and East Asia, as well as among Native Americans.

- Haplogroup S[40] – extended among indigenous Australians

- Haplogroup X[41] – found most often in Western Eurasia, but also present in the Americas.[25]

- Haplogroup X1 – found primarily in North Africa as well as in some populations of the Levant, notably among the Druze

- Haplogroup X2 – found in Western Eurasia, Siberia and among Native Americans

- Haplogroup R[42] – a very extended and diversified macro-haplogroup.

Additionally, there are some unnamed N* lineages in South Asia, among indigenous Australians and the Ket people of central Siberia.[25]

Subclades

Tree

This phylogenetic tree of haplogroup N subclades is based on the paper by Mannis van Oven and Manfred Kayser Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation[9] and subsequent published research.

See also

|

Phylogenetic tree of human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mitochondrial Eve (L) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L0 | L1–6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M | N | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CZ | D | E | G | Q | O | A | S | R | I | W | X | Y | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C | Z | B | F | R0 | pre-JT | P | U | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HV | JT | K | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H | V | J | T | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- 1 2 Soares, Pedro; Ermini, Luca; Thomson, Noel; Mormina, Maru; Rito, Teresa; Röhl, Arne; Salas, Antonio; Oppenheimer, Stephen; MacAulay, Vincent; Richards, Martin B. (2009). "Correcting for Purifying Selection: An Improved Human Mitochondrial Molecular Clock". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 84 (6): 740–59. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.001. PMC 2694979. PMID 19500773.

- ↑ MacAulay, V.; Hill, C; Achilli, A; Rengo, C; Clarke, D; Meehan, W; Blackburn, J; Semino, O; et al. (2005). "Single, Rapid Coastal Settlement of Asia Revealed by Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genomes". Science. 308 (5724): 1034–36. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1034M. doi:10.1126/science.1109792. PMID 15890885.

Haplogroup L3 (the African clade that gave rise to the two basal non-African clades, haplogroups M and N) is 84,000 years old, and haplogroups M and N themselves are almost identical in age at 63,000 years old, with haplogroup R diverging rapidly within haplogroup N 60,000 years ago.

- ↑ Richards, Martin; Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Kivisild, Toomas; Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006). "A Model for the Dispersal of Modern Humans out of Africa". In Bandelt, Hans-Jürgen; Macaulay, Vincent; Richards, Martin. Human Mitochondrial DNA and the Evolution of Homo sapiens. Nucleic Acids and Molecular Biology. 18. pp. 225–65. doi:10.1007/3-540-31789-9_10. ISBN 978-3-540-31788-3.

subclades. L3b d, L3e and L3f, for instance, are clearly of African origin, whereas haplogroup N is of apparently Eurasian origin

- 1 2 Gonder, M. K.; Mortensen, H. M.; Reed, F. A.; De Sousa, A.; Tishkoff, S. A. (2006). "Whole-mtDNA Genome Sequence Analysis of Ancient African Lineages". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (3): 757–68. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl209. PMID 17194802.

- 1 2 Olivieri, A.; Achilli, A.; Pala, M.; Battaglia, V.; Fornarino, S.; Al-Zahery, N.; Scozzari, R.; Cruciani, F.; Behar, D. M.; Dugoujon, J.-M.; Coudray, C.; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. S.; Semino, O.; Bandelt, H.-J.; Torroni, A. (2006). "The mtDNA Legacy of the Levantine Early Upper Palaeolithic in Africa". Science. 314 (5806): 1767–70. Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1767O. doi:10.1126/science.1135566. PMID 17170302.

The scenario of a back-migration into Africa is supported by another feature of the mtDNA phylogeny. Haplogroup M's Eurasian sister clade, haplogroup N, which has a very similar age to M and no indication of an African origin

- 1 2 3 Abu-Amero, Khaled K; Larruga, José M; Cabrera, Vicente M; González, Ana M (2008). "Mitochondrial DNA structure in the Arabian Peninsula". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8: 45. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-45. PMC 2268671. PMID 18269758.

- 1 2 Kivisild T, Rootsi S, Metspalu M, et al. (2003). "The genetic heritage of the earliest settlers persists both in Indian tribal and caste populations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (2): 313–32. doi:10.1086/346068. PMC 379225. PMID 12536373. "Also, the lack of L3 lineages other than M and N in India and among non-African mitochondria in general suggests that the earliest migration(s) of modern humans already carried these two mtDNA ancestors, via a departure route over the horn of Africa."

- ↑ Kivisild; et al. (2007). "Genetic Evidence of Modern Human Dispersals in South Asia". The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia.

- 1 2 van Oven M, Kayser M (2009). "Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation". Human Mutation. 30 (2): E386–94. doi:10.1002/humu.20921. PMID 18853457.

- 1 2 González, Ana M; Larruga, José M; Abu-Amero, Khaled K; Shi, Yufei; Pestano, José; Cabrera, Vicente M (2007). "Mitochondrial lineage M1 traces an early human backflow to Africa". BMC Genomics. 8: 223. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-223. PMC 1945034. PMID 17620140.

- ↑ Torroni, A; Achilli, A; MacAulay, V; Richards, M; Bandelt, H (2006). "Harvesting the fruit of the human mtDNA tree". Trends in Genetics. 22 (6): 339–45. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.001. PMID 16678300.

- 1 2 MacAulay, V.; Hill, C; Achilli, A; Rengo, C; Clarke, D; Meehan, W; Blackburn, J; Semino, O; et al. (2005). "Single, Rapid Coastal Settlement of Asia Revealed by Analysis of Complete Mitochondrial Genomes". Science. 308 (5724): 1034–36. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1034M. doi:10.1126/science.1109792. PMID 15890885.

- 1 2 3 Palanichamy MG, Sun C, Agrawal S, et al. (2004). "Phylogeny of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup N in India, based on complete sequencing: implications for the peopling of South Asia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (6): 966–78. doi:10.1086/425871. PMC 1182158. PMID 15467980.

- 1 2 Maji, Suvendu; Krithika, S.; Vasulu, T. S. (2008). "Distribution of Mitochondrial DNA Macrohaplogroup N in India with Special Reference to Haplogroup R and its Sub-Haplogroup U" (PDF). International Journal of Human Genetics. 8 (1–2): 85–96.

- 1 2 3 4 Derenko, M; Malyarchuk, B; Grzybowski, T; Denisova, G; Dambueva, I; Perkova, M; Dorzhu, C; Luzina, F; Lee, H; Vanecek, Tomas; Villems, Richard; Zakharov, Ilia (2007). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA in Northern Asian Populations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 81 (5): 1025–41. doi:10.1086/522933. PMC 2265662. PMID 17924343.

- ↑ Hervella, M.; et al. (2016). "The mitogenome of a 35,000-year-old Homo sapiens from Europe supports a Paleolithic back-migration to Africa". Scientific Reports. 6: 25501. Bibcode:2016NatSR...625501H. doi:10.1038/srep25501. PMC 4872530. PMID 27195518.

- ↑ Bernard Secher; Rosa Fregel; José M Larruga; Vicente M Cabrera; Phillip Endicott; José J Pestano; Ana M González (2014). "The history of the North African mitochondrial DNA haplogroup U6 gene flow into the African, Eurasian and American continents". Scientific Reports. 14: 109. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-14-109.

- 1 2 Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (2016). "The genetic structure of the world's first farmers". bioRxiv 059311.

- ↑ Schuenemann, Verena J.; et al. (2017). "Ancient Egyptian mummy genomes suggest an increase of Sub-Saharan African ancestry in post-Roman periods". Nature Communications. 8: 15694. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815694S. doi:10.1038/ncomms15694. PMC 5459999. PMID 28556824.

- ↑ Lipson, Mark; et al. (2017). "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers". Nature. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ↑ Fernández, Eva; et al. (2014). "Ancient DNA analysis of 8000 BC near eastern farmers supports an early neolithic pioneer maritime colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands". PLoS Genetics. 10 (6): e1004401. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401. PMC 4046922. PMID 24901650.

- ↑ Černý, Viktor; et al. (2009). "Out of Arabia—the settlement of island Soqotra as revealed by mitochondrial and Y chromosome genetic diversity" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 138 (4): 439–47. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20960. PMID 19012329. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Non, Amy. "Analyses of Genetic Data Within an Interdisciplinary Framework to Investigate Recent Human Evolutionary History and Complex Disease" (PDF). University of Florida. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ↑ Asmahan Bekada; Lara R. Arauna; Tahria Deba; Francesc Calafell; Soraya Benhamamouch; David Comas (September 24, 2015). "Genetic Heterogeneity in Algerian Human Populations". PLoS ONE. 10 (9): e0138453. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1038453B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138453. PMC 4581715. PMID 26402429. Retrieved 12 May 2016. ; S5 Table

- 1 2 3 4 Ian Logan's mtDNA site

- ↑ A. Stevanovitch; A. Gilles; E. Bouzaid; R. Kefi; F. Paris; R. P. Gayraud; J. L. Spadoni; F. El-Chenawi; E. Béraud-Colomb (January 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Diversity in a Sedentary Population from Egypt". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (1): 23–39. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00057.x. PMID 14748828. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- 1 2 Sebastian Lippold, Hongyang Xu, Albert Ko, Anne Butthof, Mingkun Li, Gabriel Renaud, Roland Schröder, and Mark Stoneking, "Human paternal and maternal demographic histories: insights from high-resolution Y chromosome and mtDNA sequences." bioRxiv posted online January 13, 2014. doi:10.1101/001792

- ↑ "Haplogroups I & N". Ianlogan.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Turchi, Chiara; Buscemi, Loredana; Previderè, Carlo; Grignani, Pierangela; Brandstätter, Anita; Achilli, Alessandro; Parson, Walther; Tagliabracci, Adriano; Ge.f.i., Group (2007). "Italian mitochondrial DNA database: results of a collaborative exercise and proficiency testing". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 122 (3): 199–204. doi:10.1007/s00414-007-0207-1. PMID 17952451.

- ↑ "Haplogroup W". Ianlogan.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Metspalu M, Kivisild T, Metspalu E, et al. (2004). "Most of the extant mtDNA boundaries in south and southwest Asia were likely shaped during the initial settlement of Eurasia by anatomically modern humans". BMC Genetics. 5: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-5-26. PMC 516768. PMID 15339343.

- 1 2 Kong, Qing-Peng et al 2011, Large-Scale mtDNA Screening Reveals a Surprising Matrilineal Complexity in East Asia and Its Implications to the Peopling of the Region.

- ↑ "Haplogroup Y". Ianlogan.co.uk. 2009-09-22. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Gunnarsdóttir, Ellen et al 2010, High-throughput sequencing of complete human mtDNA genomes from the Philippines

- ↑ "Hudjashov". Ianlogan.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ Pierson MJ, Martinez-Arias R, Holland BR, Gemmell NJ, Hurles ME, Penny D (2006). "Deciphering past human population movements in Oceania: provably optimal trees of 127 mtDNA genomes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (10): 1966–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl063. PMC 2674580. PMID 16855009.

- ↑ Hill, C.; Soares, P.; Mormina, M.; MacAulay, V.; Meehan, W.; Blackburn, J.; Clarke, D.; Raja, J. M.; Ismail, P.; Bulbeck, D.; Oppenheimer, S.; Richards, M. (2006). "Phylogeography and Ethnogenesis of Aboriginal Southeast Asians". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 23 (12): 2480–91. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl124. PMID 16982817.

- ↑ Adrien Rieux, Anders Eriksson, Mingkun Li, et al., "Improved Calibration of the Human Mitochondrial Clock Using Ancient Genomes." Mol Biol Evol (2014) doi:10.1093/molbev/msu222

- ↑ "Haplogroup A". Ianlogan.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ "Haplogroup S". Ianlogan.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ "Haplogroup X". Ianlogan.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ↑ "Haplogroup R*". Ianlogan.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haplogroup N (mtDNA). |

- Haplogroup N

- Mannis van Oven's – mtDNA subtree N

- Spread of Haplogroup N, from National Geographic

- Hudjashov, G.; Kivisild, T.; Underhill, P. A.; Endicott, P.; Sanchez, J. J.; Lin, A. A.; Shen, P.; Oefner, P.; Renfrew, C.; Villems, R.; Forster, P. (2007). "Revealing the prehistoric settlement of Australia by Y chromosome and mtDNA analysis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (21): 8726–30. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8726H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702928104. PMC 1885570. PMID 17496137.

- Katherine Borges' The Haplogroup N mtDNA Study at Family Tree DNA

- General

- Ian Logan's Mitochondrial DNA Site