Scythian religion

Scythian religion refers to the mythology, ritual practices and beliefs of the Scythians, an ancient Iranian people who dominated Central Asia and the Pontic-Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe throughout Classical Antiquity. What little is known of the religion is drawn from the work of the 5th century Greek historian and ethnographer Herodotus. Scythian religion is assumed to have been related to the earlier Proto-Indo-Iranian religion, and to have influenced later Slavic, Hungarian and Turkic mythologies, as well as some contemporary Eastern Iranian and Ossetian traditions. It has several similarities to the still extant Iranian Zoroastrian religion.

Archaeological context

The primary archaeological context of horse sacrifice are burials, notably chariot burials, but graves with horse remains reach from the Eneolithic well into historical times. Herodotus describes the execution of horses at the burial of a Scythian king, and Iron Age kurgan graves known to contain horses number in the hundreds.

The Scythians had some reverence for the stag, which is one of the most common motifs in their artwork, especially at funeral sites (see, for example, the Pazyryk burials). Herodotus describes deer as being sacrificed exclusively to Tabiti, leading some researchers to suspect an influence of siberian deer goddess cults in Scythian religion.[2]

Pantheon

According to Herodotus, the Scythians worshipped a pantheon of seven gods and goddesses (heptad), which he equates with Greek divinities of Classical Antiquity following the interpretatio graeca. He mentions eight deities in particular, the eighth being worshipped by the Royal Scythians, and gives the Scythian names for seven of them as follows:[3]

Animal sacrifice

The mode of Scythian animal sacrifice was, in the opinion of Herodotus, relatively simple. Sacrificial animals included various kinds of livestock, though the most prestigious offering was considered to be the horse. The pig, on the other hand, was never offered in sacrifice, and apparently the Scythians were loath to keep swine within their lands.[5] Herodotus describes the Scythian manner of sacrifice as follows:

The victim stands with its fore-feet tied, and the sacrificing priest stands behind the victim, and by pulling the end of the cord he throws the beast down; and as the victim falls, he calls upon the god to whom he is sacrificing, and then at once throws a noose round its neck, and putting a small stick into it he turns it round and so strangles the animal, without either lighting a fire or making any first offering from the victim or pouring any libation over it: and when he has strangled it and flayed off the skin, he proceeds to boil it. [...] Then when the flesh is boiled, the sacrificer takes a first offering of the flesh and of the vital organs and casts it in front of him.[6]

Worship of "Scythian Ares"

Although Tabiti was apparently the most important deity in the Scythian pantheon, the worship accorded to the deity Herodotus refers to as "Ares" was unique. He notes that "it is not their custom [...] to make images, altars or temples to any except Ares, but to him it is their custom to make them".[6] He describes the construction of the altar and the subsequent sacrifice as follows:

In each district of the several governments they have a temple of Ares set up in this way: bundles of brushwood are heaped up for about three furlongs in length and in breadth, but less in height; and on the top of this there is a level square made, and three of the sides rise sheer but by the remaining one side the pile may be ascended. Every year they pile on a hundred and fifty wagon-loads of brushwood, for it is constantly settling down by reason of the weather. Upon this pile of which I speak each people has an ancient iron sword set up, and this is the sacred symbol of Ares. To this sword they bring yearly offerings of cattle and of horses; and they have the following sacrifice in addition, beyond what they make to the other gods, that is to say, of all the enemies whom they take captive in war they sacrifice one man in every hundred, not in the same manner as they sacrifice cattle, but in a different manner: for they first pour wine over their heads, and after that they cut the throats of the men, so that the blood runs into a bowl; and then they carry this up to the top of the pile of brushwood and pour the blood over the sword. This, I say, they carry up; and meanwhile below by the side of the temple they are doing thus: they cut off all the right arms of the slaughtered men with the hands and throw them up into the air, and then when they have finished offering the other victims, they go away; and the arm lies wheresoever it has chanced to fall, and the corpse apart from it.[5]

According to Tadeusz Sulimirski, this form of worship continued among the descendants of the Scythians, the Alans, through to the 4th century CE.[7]; this tradition may be reflected in Jordanes' assertion that Attila was able to assert his authority over the Scythians through his possession of the "Sword of Mars"[8].

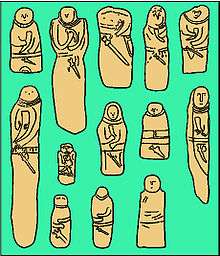

In spite of this, however, a variety of goddess figurines are present in kurgans.[9][10][11]

Enarei

The Enarei were a privileged caste of hereditary priests which played an important political role in Scythian society as they were believed to have received the gift of prophesy directly from the goddess Argimpasa.[12] The method employed by the Enarei differed from that practised by traditional Scythian diviners: whereas the latter used a bundle of willow rods, the Enarei used strips cut from the bark of the linden tree (genus tilia) to tell the future. The Enarei were also noted for dressing themselves in the clothes of women, a custom which Herodotus understands as being reflected in the title ena-rei, glossing this as ἀνδρό-γυνοι or "man-women".[12]

Connection to Zoroastrianism

As an Iranian religion, the practises of the Scythians bear some similarities with modern Zoroastrianism. The supposed relevance of a Hestia-analogue has been interpreted as a shared veneration of the sacred fire (see also: Atar), and the lack of iconography is similar to modern Zoroastrian rejections of visual representations of Ahura Mazda.[13]

See also

Notes

- ↑ redrawn from B. A. Rybakov, Язычество древней Руси ("Paganism of Ancient Rus", 1987, fig. 7).

- ↑ Esther Jacobson, The Deer Goddess of Ancient Siberia: A Study in the Ecology of Belief, BRILL, 01/01/1993

- ↑ Macaulay (1904:314). Cf. also Rolle (1980:128–129); Hort (1827:188–190).

- ↑ West, M. L. Indo-European Poetry and Myth. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- 1 2 Macaulay (1904:315).

- 1 2 Macaulay (1904:314).

- ↑ Sulimirski (1985:158–159).

- ↑ Geary (1994:63).

- ↑

- ↑ Mozolevskiî, B. M. 1979. Tovsta mogila. Kiev: Naukova dumka.

- ↑ Bessonova, S. S. 1983. Religioznïe predstavleniia skifov. Kiev: Naukova dumka

- 1 2 Macaulay (1904:317); Christian (1998:148).

- ↑ Mary Boyce, A History of Zoroastrianism: Volume II: Under the Achaemenians, BRILL, 1982

References

- Christian, David (1998). A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Volume I: Inner Eurasia from Prehistory to the Mongol Empire. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-18321-3. pg. 148.

- Geary, Patrick J. (1994). "Chapter 3. Germanic Tradition and Royal Ideology in the Ninth Century: The Visio Karoli Magni". Living with the Dead in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8014-8098-0.

- Hort, W. Jillard (1827). The New Pantheon: An Introduction to the Mythology of the Ancients. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green. pp. 188–190.

- Macaulay, G. C. (1904). The History of Herodotus, Vol. I. London: Macmillan & Co. pp. 313–317.

- Rolle, Renate (1980). The World of the Scythians. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06864-5. pp. 128–129.

- Sulimirski, T. (1985). "The Scyths" in: Fisher, W. B. (Ed.) The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 2: The Median and Achaemenian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20091-1. pp. 158–159.