Blond

Blond or fair hair is a hair color characterized by low levels of the dark pigment eumelanin. The resultant visible hue depends on various factors, but always has some yellowish color. The color can be from the very pale blond (caused by a patchy, scarce distribution of pigment) to reddish "strawberry" blond or golden-brownish ("sandy") blond colors (the latter with more eumelanin). Because hair color tends to darken with age, natural blond hair is generally very rare in adulthood. Naturally-occurring blond hair is primarily found in populations of northern European descent and is believed to have evolved to enable more efficient synthesis of vitamin D, due to northern Europe's lower levels of sunlight. Blond hair has also developed in other populations, although it is usually not as common, and can be found among natives of the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and Fiji, among the Berbers of North Africa, and among some Asians.

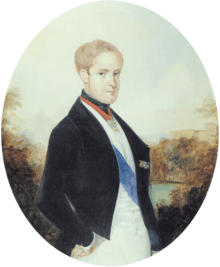

In human culture, blond hair has long been associated with female beauty. Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty, was reputed to have blond hair. In ancient Greece and Rome, blond hair was frequently associated with prostitutes, who dyed their hair using saffron dyes in order to attract customers. The Greeks stereotyped Thracians and slaves as blond and the Romans associated blondness with the Celts and the Germans to the north. In western Europe during the Middle Ages, long, blond hair was idealized as the paragon of female beauty. The Norse goddess Sif and the medieval heroine Iseult were both significantly portrayed as blond and, in medieval artwork, Eve, Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin Mary are often shown with blond hair. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, scientific racists categorized blond hair and blue eyes as characteristics of the supreme Nordic race. In contemporary western culture, blonde women are often negatively stereotyped as sexually attractive, but unintelligent.

Etymology, spelling, and grammar

Origins and meanings

The word "blond" is first documented in English in 1481[1] and derives from Old French blund, blont, meaning "a colour midway between golden and light chestnut".[2] It gradually eclipsed the native term "fair", of same meaning, from Old English fæġer, causing "fair" later to become a general term for "light complexioned". This earlier use of "fair" survives in the proper name Fairfax, from Old English fæġer-feahs meaning "blond hair".

The word "blond" has two possible origins. Some linguists say it comes from Medieval Latin blundus, meaning "yellow", from Old Frankish blund which would relate it to Old English blonden-feax meaning "grey-haired", from blondan/blandan meaning "to mix" (Cf. blend). Also, Old English beblonden meant "dyed", as ancient Germanic warriors were noted for dyeing their hair. However, linguists who favor a Latin origin for the word say that Medieval Latin blundus was a vulgar pronunciation of Latin flavus, also meaning "yellow". Most authorities, especially French, attest to the Frankish origin. The word was reintroduced into English in the 17th century from French, and was for some time considered French; in French, "blonde" is a feminine adjective; it describes a woman with blond hair.[3]

Usage

"Blond", with its continued gender-varied usage, is one of few adjectives in written English to retain separate masculine and feminine grammatical genders. Each of the two forms, however, is pronounced identically. American Heritage's Book of English Usage propounds that, insofar as "a blonde" can be used to describe a woman but not a man who is merely said to possess blond(e) hair, the term is an example of a "sexist stereotype [whereby] women are primarily defined by their physical characteristics."[4] The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) records that the phrase "big blond beast" was used in the 20th century to refer specifically to men "of the Nordic type" (that is to say, blond-haired).[5] The OED also records that blond as an adjective is especially used with reference to women, in which case it is likely to be spelt "blonde", citing three Victorian usages of the term. The masculine version is used in the plural, in "blonds of the European race",[5] in a citation from 1833 Penny cyclopedia, which distinguishes genuine blondness as a Caucasian feature distinct from albinism.[6]

By the early 1990s, "blonde moment" or being a "dumb blonde" had come into common parlance to mean "an instance of a person, esp. a woman... being foolish or scatter-brained."[7] Another hair color word of French origin, brunet(te) (from the same Germanic root that gave "brown"), functions in the same way in orthodox English. The OED gives "brunet" as meaning "dark-complexioned" or a "dark-complexioned person", citing a comparative usage of brunet and blond to Thomas Henry Huxley in saying, "The present contrast of blonds and brunets existed among them."[8] "Brunette" can be used, however, like "blonde", to describe a mixed-gender populace. The OED quotes Grant Allen, "The nation which resulted... being sometimes blonde, sometimes brunette."[9]

"Blond" and "blonde" are also occasionally used to refer to objects that have a color reminiscent of fair hair. For example, the OED records its use in 19th-century poetic diction to describe flowers, "a variety of clay ironstone of the coal measures", "the colour of raw silk",[5] a breed of ray, lager beer, and pale wood.[10]

Varieties

Various subcategories of blond hair have been defined to describe the different shades and sources of the hair color more accurately. Common examples include the following:

- ash-blond:[11] ashen or grayish blond.

- bleached blond, bottle blond, or peroxide blond:[12] terms used to refer to artificially colored blond hair.

- blond/flaxen:[13][14] when distinguished from other varieties, "blond" by itself refers to a light but not whitish blond, with no traces of red, gold, or brown; this color is often described as "flaxen".

- dirty blond[15] or dishwater blond:[16] dark blond with flecks of golden blond and brown.

- golden blond: a darker to rich, golden-yellow blond (found mostly in Northeastern Europe, i.e., Russia, Estonia).

- honey blond: dark iridescent blond.

- platinum blond[17] or towheaded:[18][19] whitish-blond; almost all platinum blonds are children, although it is found on people in Northern Europe. "Platinum blond" is often used to describe bleached hair, while "towheaded" generally refers to natural hair color.

- sandy blond:[20][21] grayish-hazel or cream-colored blond.

- strawberry blond[22] or Venetian blond: reddish blond[23][24][25][26][27]

- yellow: yellow-blond ("yellow" can also be used to refer to hair which has been dyed yellow).

A woman with long blond hair

A woman with long blond hair A young man with light blond hair

A young man with light blond hair A woman with long, dark blond hair from behind

A woman with long, dark blond hair from behind

Evolution of blond hair

Natural lighter hair colors occur most often in Europe and less frequently in other areas.[28] In Northern European populations, the occurrence of blond hair is very frequent. The hair color gene MC1R has at least seven variants in Europe, giving the continent a wide range of hair and eye shades. Based on a genetic research carried out at three Japanese universities, the date of the genetic mutation that resulted in blond hair in Europe has been isolated to about 11,000 years ago during the last ice age.[29]

A typical explanation found in the scientific literature for the evolution of light hair is related to the evolution of light skin, and in turn the requirement for vitamin D synthesis and northern Europe's seasonal less solar radiation.[30] Lighter skin is due to a low concentration in pigmentation, thus allowing more sunlight to trigger the production of vitamin D. In this way, high frequencies of light hair in northern latitudes are a result of the light skin adaptation to lower levels of solar radiation, which reduces the prevalence of rickets caused by vitamin D deficiency. The darker pigmentation at higher latitudes in certain ethnic groups such as the Inuit is explained by a greater proportion of seafood in their diet and by the climate which they live in, because in the polar climate there is more ice or snow on the ground, and this reflects the solar radiation onto the skin, making this environment lack the conditions for the person to have blond, brown or red hair, light skin and blue, grey or green eyes.

An alternative hypothesis was presented by Canadian anthropologist Peter Frost, who claims blond hair evolved very quickly in a specific area at the end of the last ice age by means of sexual selection.[31] According to Frost, the appearance of blond hair and blue eyes in some northern European women made them stand out from their rivals, and more sexually appealing to men, at a time of fierce competition for scarce males.[31][32]

The derived allele of KITLG associated with blond hair in modern Europeans is present in several individuals of the Ancient North Eurasian (ANE) lineage, and is recorded in Mesolithic Eastern Europe as associated with the Eastern European Hunter-Gatherer (EHG) lineage derived from ANE. The earliest known individual with the derived allele is the ANE Afontova Gora 3 individual, dated to 14,700 years ago.[33] Ancient DNA of ANE or "steppe" ancestry is found in Mesolithic Northern Europe.

A 2014 study reported seven Mesolithzic hunter-gatherers found at Motala, southern Sweden, dated to 7,700 years ago, as the earliest known individuals in whom the modern Scandinavian phenotype, combining light skin, blue eyes and blond hair, was combined. These individuals had light skin gene alleles in SLC24A5 and SLC45A2, and HERC2/OCA2 alleles associated with blue eyes (also contributes to lighter skin and blond hair).[34] Light pigmentation traits had thus already existed in pre-Indo-European Europeans, since at least the later Mesolithic.[35] Later individuals with Yamnaya ancestry, by contrast, were predominantly dark-eyed (brown), dark-haired and had a skin colour that was moderately light, though somewhat darker than that of the average modern European.[36]

It is possible that blond hair evolved more than once. A 2012 study published in Science reported a distinct genetic origin of blond hair in people from the Solomon Islands in Melanesia, associated with an amino acid change in TYRP1 produced blond hair.[37][38]

Prevalence

Blond hair is most common in light-skinned infants and children,[39] so much so that the term "baby blond" is often used for very light colored hair. Babies may be born with blond hair even among groups where adults rarely have blond hair, although such natural hair usually falls out quickly. Blond hair tends to turn darker with age, and many children's blond hair turns light, medium, dark brown or black before or during their adult years.[39] Because blond hair tends to turn brunette with age, natural blond hair is rare in adulthood;[40][41] according to the sociologist Christie Davies, only around five percent of adults in Europe and North America are naturally blond.[40] A study conducted in 2003 concluded that only four percent of American adults are naturally blond.[41] Nonetheless, a significant majority of Caucasian women (perhaps as high as three in four) dye their hair blond, a significantly higher percentage than for any other hair color.[40][42]

Europe

Blond hair is most common in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea countries, where true blondism is believed to have originated. The pigmentation of both hair and eyes is lightest around the Baltic Sea, and darkness increases regularly and almost concentrically around this region.[43]

In France, according to a source published 1939, blondism is more common in Normandy, and less common in the Pyrenees and the Mediterranean seacoast; 26% of French population has blond or light brown hair.[44] A 2007 study of French females showed that by then roughly 20% were blonde, although half of these blondes were fully fake. Roughly ten percent of French females are natural blondes, of which 60% bleach their hair to a lighter tone of blond.[45]

In Portugal, an average 11% of the population shows traces of blondism, peaking at 14.3–15.1% blond people in Póvoa de Varzim in northern Portugal.[46][47] In northern Spain, 17% of the population shows traces of blondism, but in southern Spain just 2% of the people are blond.[48] In Italy, a study of Italian men conducted by Ridolfo Livi between 1859 and 1863 on the records of the National Conscription Service showed that 8.2% of Italian men exhibited blond hair. Blondism frequency varies among regions from 12.6% in Veneto, to 1.7% in Sardinia.[49] In a more detailed study from the 20th-century geneticist Renato Biasutti,[50] the regional contrasts of blondism frequency are better shown, with a greater occurrence in the northern regions where the figure could be over 20%, and a lesser occurrence in the south such as Sardinia where the frequency was less than 2.4%. With the exception of Benevento and the surrounding area where various shades of blond hair were present in 10%–14.9% of the population, other southern regions averaged between 2.5% and 7.4%.[51]

Africa

Blondism is a common sight among Berbers of North Africa, especially in the Rif and Kabyle region. Blondism frequency varies among Berbers from 1% among Jerban Berbers and 4% among Mozabite Berbers and Shawia Berbers, to 11% among Kabyle Berbers.[52] In South Africa where there is a significant population of whites, mainly from Dutch and English ancestry, blond people may account for 3-4% of the South African population.

A number of blond naturally mummified bodies of common people (i.e. not proper mummies) dating to Roman times have been found in the Fagg El Gamous cemetery in Egypt. "Of those whose hair was preserved 54% were blondes or redheads, and the percentage grows to 87% when light-brown hair color is added."[53] Excavations have been ongoing since the 1980s. Burials seem to be clustered by hair-colour.[54]

Oceania

Aboriginal Australians, especially in the west-central parts of the continent, have a high frequency of natural blond-to-brown hair. Blondness is also found in some other parts of the South Pacific, such as the Solomon Islands,[37][38] Vanuatu, and Fiji, again with higher incidences in children. Blond hair in Melanesians is caused by an amino acid change in the gene TYRP1.[37] This mutation is at a frequency of 26% in the Solomon Islands and is absent outside of Oceania.[37]

Asia

Blond hair can be found in any region of Asia, including West Asia, East Asia, Central Asia, and South Asia. In these parts of Asia, blond hair is generally seen among children and usually turns into a shade of dark brown in adulthood. Environmental factors, such as sun exposure and nutrition status, often contribute to changes in hair color in Asia.[55] Genetic research published in 2014, 2015 and 2016 found that Yamnaya Proto-Indo-Europeans, who migrated to Europe in the early Bronze Age were overwhelmingly dark-eyed (brown) and dark-haired, and had a skin colour that was moderately light, though somewhat darker than that of the average modern European.[36] While light pigmentation traits had already existed in pre-Indo-European Europeans (both farmers and hunter-gatherers), long-standing philological attempts to correlate them with the arrival of Indo-Europeans from the steppes were misguided.[35]

According to genetic studies, Yamnaya Proto-Indo-European migration to Europe led to Corded Ware culture, where Yamnaya Proto-Indo-Europeans mixed with "Scandinavian hunter-gatherer" women who carried genetic alleles HERC2/OCA2, which causes a combination of blue eyes and blond hair.[56][57][34] Proto-Indo-Iranians who split from Corded Ware culture formed the Andronovo culture and are believed to have spread genetic alleles HERC2/OCA2 that cause blond hair to parts of West Asia, Central Asia and South Asia.[57] Genetic analysis in 2014 also found that people of the Afanasevo culture which flourished in the Altai Mountains were genetically identical to Yamnaya Proto-Indo-Europeans and that they did not carry genetic alleles for blond hair or light eyes.[58][56][57] The Afanasevo culture was later replaced by a second wave of Indo-European invaders from the Andronovo culture, who were a product of Corded Ware admixture that took place in Europe, and carried genetic alleles that cause blond hair and light eyes.[58][56][57] In 2009 and 2014, genomic study of Tarim mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin in present-day Xinjiang, China, showed that they were also a product of a Corded Ware admixture and were genetically closer to the Andronovo culture (which split from Corded Ware culture)[57] than to the Yamnaya culture or Afanasevo culture.[59][58]

Today, higher frequencies of light hair in Asia are more prevalent among Pamiris, Kalash, Nuristani and Uyghur children than in adult populations of these ethnic groups.[60] About 75% of Russia is geographically considered North Asia; however, the Asian portion of Russia contributes to only an estimate of 20% of Russia's total population.[61] North Asia's population has an estimate of 1-19% with light hair.[62][63] From the times of the Russian Tsardom of the 17th century through the Soviet Union rule in the 20th century, many ethnic Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Latvians, and Estonians were settled in or exiled en masse to Siberia and Central Asia. Blond hair is often seen in these groups, whereas the indigenous peoples are more likely to be dark haired.[64][65][66] For instance, their descendants currently contribute to an estimated 25% of Kazakhstan's total population.[67]

Americas

Many actors and actresses in Latin America and Hispanic United States have blond hair, blue eyes, and pale skin.[68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76]

Historical cultural perceptions

Ancient Greece

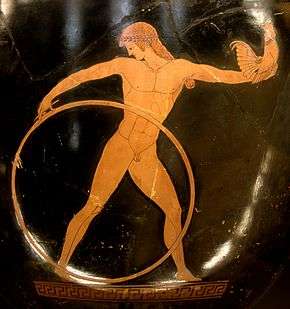

Right image: Ganymede, a Trojan youth, rolling a hoop, Attic vase c. 500 BC.

Most people in ancient Greece had dark hair and, as a result of this, the Greeks found blond hair immensely fascinating.[77] In the Homeric epics, Menelaus the king of the Spartans is, together with some other Achaean leaders, portrayed as blond.[78] Other blond characters in the Homeric poems are Peleus, Achilles, Meleager, Agamede, and Rhadamanthys.[78] Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love and beauty, was often described as golden-haired and portrayed with this color hair in art.[79] Aphrodite's master epithet in the Homeric epics is Χρυσεη (Khryseē), which means "golden".[80] The traces of hair color on Greek korai probably reflect the colors the artists saw in natural hair;[81] these colors include a broad diversity of shades of blond, red, and brown.[81] The minority of statues with blond hair range from strawberry blond up to platinum blond.[81]

Sappho of Lesbos (c. 630-570 BC) wrote that purple-colored wraps as headdress were good enough, except if the hair was blond: "...for the girl who has hair that is yellower than a torch [it is better to decorate it] with wreaths of flowers in bloom."[82] Sappho also praises Aphrodite for her golden hair, stating that since gold metal is free from rust, the goddess's golden hair represents her freedom from ritual pollution.[80] Sappho's contemporary Alcman of Sparta praised golden hair as one of the most desirable qualities of a beautiful woman,[80] describing in various poems "the girl with the yellow hair" and a girl "with the hair like purest gold."[80]

In the fifth century BC, the sculptor Pheidias may have depicted the Greek goddess of wisdom Athena's hair using gold in his famous statue of Athena Parthenos, which was displayed inside the Parthenon.[83] The Greeks thought of the Thracians who lived to the north as having reddish-blond hair.[84] Because many Greek slaves were captured from Thrace, slaves were stereotyped as blond or red-headed.[84] "Xanthias" (Ξανθίας), meaning "reddish blond", was a common name for slaves in ancient Greece[84][85] and a slave by this name appears in many of the comedies of Aristophanes.[85]

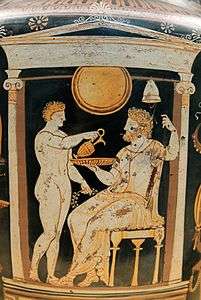

The most famous statue of Aphrodite, the Aphrodite of Knidos, sculpted in the fourth century BC by Praxiteles, represented the goddess's hair using gold leaf[86] and contributed to the popularity of the image of Aphrodite as a blonde goddess.[87] Greek prostitutes frequently dyed their hair blond using saffron dyes or colored powders.[88] Blond dye was highly expensive, took great effort to apply, and smelled repugnant,[88] but none of these factors inhibited Greek prostitutes from dying their hair.[88] As a result of this and the natural rarity of blond hair in the Mediterranean region, by the fourth century BC, blond hair was inextricably associated with prostitutes.[88] The comic playwright Menander (c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) protests that "no chaste woman ought to make her hair yellow."[88] At another point, he deplores blond hair dye as dangerous: "What can we women do wise or brilliant, who sit with hair dyed yellow, outraging the character of gentlewomen, causing the overthrow of houses, the ruin of nuptials, and accusations on the part of children?"[88] Historian and Egyptologist Joann Fletcher asserts that the Macedonian ruler Alexander the Great and members of the Macedonian-Greek Ptolemaic dynasty of Hellenistic Egypt had blond hair, such as Arsinoe II and Berenice II.[89] Historian Michael Grant notes that Ptolemy II Philadelphus, pharaoh and husband to Queen Arsinoe II, also had blond hair.[90]

The male figure of the Etruscan sarcophagus known as the Sarcophagus of the Spouses (Louvre, Paris), 520–510 BC

The male figure of the Etruscan sarcophagus known as the Sarcophagus of the Spouses (Louvre, Paris), 520–510 BC The goddess Hera (according to the description on the cup); tondo of an Attic white-ground kylix from Vulci, c. 470 BC

The goddess Hera (according to the description on the cup); tondo of an Attic white-ground kylix from Vulci, c. 470 BC Terracotta vase in the shape of Dionysus' head, c. 410 BC; on display in the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, housed in the Stoa of Attalus

Terracotta vase in the shape of Dionysus' head, c. 410 BC; on display in the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, housed in the Stoa of Attalus- Pottery vessel of Aphrodite in a shell; from Attica, Classical Greece, discovered at Phanagoria, Taman Peninsula (Bosporan Kingdom, southern Russia), early 4th century BC, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

- An ancient Greek pottery (terracotta) figurine from Taras (modern Taranto), Magna Graecia, Altes Museum

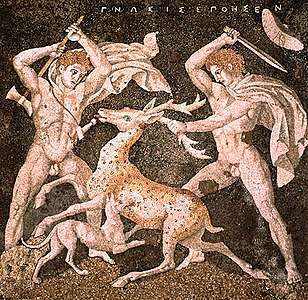

Alexander the Great (left), wearing a kausia and fighting an Asiatic lion with his friend Craterus (detail); late 4th-century BC mosaic from Pella[91]

Alexander the Great (left), wearing a kausia and fighting an Asiatic lion with his friend Craterus (detail); late 4th-century BC mosaic from Pella[91]- Apulian red-figure Oinochoe with Lid by the Ganymed Painter (Oinochoe) and Armidale Painter (Lid): head in a calyx between tendrils. About 340–310 BC. Antikensammlung Kiel.

- Detail of a krater with volutes in terracotta; Greek art from Southern Italy, c. 330–320 BC.

- A Gnathia-style ceramic vessel from ancient Magna Graecia (Apulia, Italy), depicting a blond winged youth with a Phrygian cap, with lion head spouts, by the "Toledo" painter, c. 300 BC

Woman's head on an alabastron in gnathia style; Apulian vase painting, Magna Graecia, Antikensammlung Kiel

Woman's head on an alabastron in gnathia style; Apulian vase painting, Magna Graecia, Antikensammlung Kiel Color reconstruction of statue of a young girl from the Parthenon in Athens, 520 BC. Based on analysis of trace pigments.

Color reconstruction of statue of a young girl from the Parthenon in Athens, 520 BC. Based on analysis of trace pigments..jpg) Reconstructed polychromy of a vase-shaped tombstone from Athens, c. 330 BC, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Reconstructed polychromy of a vase-shaped tombstone from Athens, c. 330 BC, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen The Greek goddess Artemis. Color reconstruction of a 1st-century AD statue found in Pompeii. Reconstructed using analysis of trace pigments. It was an imitation of Greek statues of the 6th century BC.

The Greek goddess Artemis. Color reconstruction of a 1st-century AD statue found in Pompeii. Reconstructed using analysis of trace pigments. It was an imitation of Greek statues of the 6th century BC. The Treu Head, 2nd century AD. Color reconstruction of marble head of likely a goddess. The head was found at the Esquiline Hill, Rome, and preserves numerous colour traces.

The Treu Head, 2nd century AD. Color reconstruction of marble head of likely a goddess. The head was found at the Esquiline Hill, Rome, and preserves numerous colour traces.

Roman Empire

.jpg)

On the right: detail of athletic women in the "bikini girls" mosaic of the Villa Romana del Casale, Roman Sicily, 4th century AD

During the early years of the Roman Empire, blond hair was associated with prostitutes.[92] The preference changed to bleaching the hair blond when Greek culture, which practiced bleaching, reached Rome, and was reinforced when the legions that conquered Gaul returned with blond slaves.[93] Sherrow also states that Roman women tried to lighten their hair, but the substances often caused hair loss, so they resorted to wigs made from the captives' hair.[94] According to Francis Owens, Roman literary records describe a large number of well-known Roman historical personalities as blond.[95]

Juvenal wrote in a satirical poem that Messalina, Roman empress of noble birth, would hide her black hair with a blond wig for her nightly visits to the brothel: sed nigrum flavo crinem abscondente galero intravit calidum veteri centone lupanar.[96] In his Commentary on the Aeneid of Virgil, Maurus Servius Honoratus noted that the respectable matron was only black haired, never blonde.[97] In the same passage, he mentioned that Cato the Elder wrote that some matrons would sprinkle golden dust on their hair to make it reddish-color. Emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161 – 169 AD) was said to sprinkle gold-dust on his already "golden" blond hair to make it even blonder and brighter.[98] Commodus (r. 177-192), son of Marcus Aurelius (a co-emperor with Lucius Verus), likewise had naturally curly blond hair.[99]

From an ethnic point of view, Roman authors associated blond and red hair with the Gauls and the Germans: e.g., Virgil describes the hair of the Gauls as "golden" (aurea caesaries),[100] Tacitus wrote that "the Germans have fierce blue eyes, red-blond hair (rutilae comae), huge (tall) frames";[101] in accordance with Ammianus, almost all the Gauls were "of tall stature, fair and ruddy".[102] Celtic and Germanic peoples of the provinces, among the free subjects called peregrini, served in Rome's armies as auxilia, such as the cavalry contingents in the army of Julius Caesar.[103] Some became Roman citizens as far back as the 1st century BC, following a policy of Romanization of Gaul and Lesser Germania.[104] Sometimes entire Celtic and Germanic tribes were granted citizenship, such as when emperor Otho granted citizenship to all of the Lingones in 69 AD.[105]

By the 1st century BC, the Roman Republic had expanded its control into parts of western Germany, and by 85 AD the provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superior were formally established there.[106] Yet as late as the 4th century AD, Ausonius, a poet and tutor from Burdigala, wrote a poem about an Alemanni slave girl named Bissula, who he had recently freed after she'd been taken as a prisoner of war in the campaigns of Valentinian I, noting that her adopted Latin language marked her as a woman of Latium yet her blond-haired, blue-eyed appearance ultimately signified her true origins from the Rhine.[107] Further south, the Iberian peninsula was originally inhabited by Celtiberians outside of Roman control. The gradual Roman conquest of Iberia was completed by the early 1st century AD.[108] The Romans established provinces such as Hispania Terraconensis that were inhabited largely by Gallaeci, whose red and blond-haired descendants (which also include those of Visigothic origins) have continued to inhabit northern areas of Spain such as Galicia and Portugal into the modern era.[108]

.jpg) Fresco depicting a seated woman, from the Villa Arianna at Stabiae, 1st century AD

Fresco depicting a seated woman, from the Villa Arianna at Stabiae, 1st century AD

Remnants of a Roman bust of a youth with a blond beard, perhaps depicting Roman emperor Commodus (r. 177–192), National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Remnants of a Roman bust of a youth with a blond beard, perhaps depicting Roman emperor Commodus (r. 177–192), National Archaeological Museum, Athens- A blond man in a Roman fresco from Klagenfurt, Austria, Landesmuseum für Kärnten

Roman mosaic depicting a feminine personification, from the Boathouse of Psyche in Daphne (suburb of Antioch), beginning of 3rd century AD, Louvre Museum

Roman mosaic depicting a feminine personification, from the Boathouse of Psyche in Daphne (suburb of Antioch), beginning of 3rd century AD, Louvre Museum- A boy holding a platter of fruits and what may be a bucket of crabs, in a kitchen with fish and squid, on the June panel from a mosaic depicting the months (3rd century)[109]

A mosaic of young boys hunting from the Villa Romana del Casale, Roman Sicily, 4th century AD

A mosaic of young boys hunting from the Villa Romana del Casale, Roman Sicily, 4th century AD A Roman fresco depicting the goddess Diana hunting, 4th century AD, from the Via Livenza hypogeum in Rome

A Roman fresco depicting the goddess Diana hunting, 4th century AD, from the Via Livenza hypogeum in Rome

Achilles being adored by princesses of Skyros, from a mythological scene in which Odysseus (Ulysses) discovers him dressed as a woman and hiding among the princesses at the royal court of Skyros. A late Roman mosaic from La Olmeda, Spain, 4th–5th centuries AD

Achilles being adored by princesses of Skyros, from a mythological scene in which Odysseus (Ulysses) discovers him dressed as a woman and hiding among the princesses at the royal court of Skyros. A late Roman mosaic from La Olmeda, Spain, 4th–5th centuries AD

Medieval Europe

.jpg)

Medieval Scandinavian art and literature often places emphasis on the length and color of a woman's hair,[110] considering long, blond hair to be the ideal.[110] In Norse mythology, the goddess Sif has famously blond hair, which some scholars have identified as representing golden wheat.[111] In the Old Norse Gunnlaug Saga, Helga the Beautiful, described as "the most beautiful woman in the world", is said to have hair that is "as fair as beaten gold" and so long that it can "envelope her entirely".[110] In the Poetic Edda poem Rígsþula, the blond man Jarl is considered to be the ancestor of the dominant warrior class. In Northern European folklore, supernatural beings value blond hair in humans. Blond babies are more likely to be stolen and replaced with changelings, and young blonde women are more likely to be lured away to the land of the beings.[112]

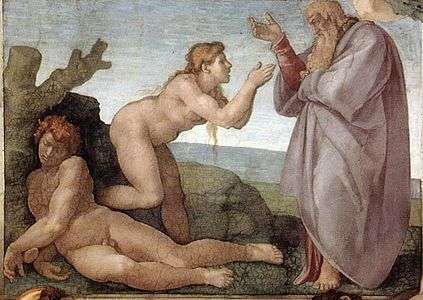

The Scandinavians were not the only ones to place strong emphasis on the beauty of blond hair;[110] the French writer Christine de Pisan writes in her book The Treasure of the City of Ladies (1404) that "there is nothing in the world lovelier on a woman's head than beautiful blond hair."[110] In medieval artwork, female saints are often shown with long, shimmering blond hair, which emphasizes their holiness and virginity.[113] At the same time, however, Eve is often shown with long, blond hair, which frames her nude body and draws attention to her sexual attractiveness.[92][114] In medieval Gothic paintings of the crucifixion of Jesus, the figure of Mary Magdalene is shown with long, blond hair, which flows down her back unbound in contrast to most of the women in the scenes, who are shown with dark hair, normally covered by a scarf.[115] In the older versions of the story of Tristan and Iseult, Tristan falls in love with Iseult after seeing only a single lock of her long, blond hair.[116] In fact, Iseult was so closely associated with blondness that, in the poems of Chrétien de Troyes, she is called "Iseult le Blonde".[116] In Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (written from 1387 until 1400), the knight describes the beautiful Princess Emily in his tale, stating, "yclothed was she fressh, for to devyse:/Hir yellow heer was broided in a tresse/Behinde hir bak, a yerde long, I gesse" (lines 1048-1050).[116]

Because of blond hair's relative commonness in northern Europe, especially among children, folk tales from these regions tend to feature large numbers of blond protagonists.[92][117] Although these stories may not have been seen by their original tellers as idealizing blond hair,[117] when they are read in cultures outside of northern Europe where blond hair "has rarity value", they may seem to connote that blond hair is a sign of special purity.[117]

During the medieval period, Spanish ladies preferred to dye their hair black, yet by the time of the Renaissance in the 16th century the fashion (imported from Italy) was to dye their hair blond or red.[118]

Fourteenth-century painting by Giusto de' Menabuoi of Adam and Eve being expelled from Eden by an angel, showing all three as blond

Fourteenth-century painting by Giusto de' Menabuoi of Adam and Eve being expelled from Eden by an angel, showing all three as blond International Gothic showing Mary Magdalene covered by her long, blond hair as she is lifted by angels in SS. Johns' Cathedral in Toruń

International Gothic showing Mary Magdalene covered by her long, blond hair as she is lifted by angels in SS. Johns' Cathedral in Toruń

_2.jpg) Adam and Eve (1507) by Albrecht Dürer, showing Eve with blond hair

Adam and Eve (1507) by Albrecht Dürer, showing Eve with blond hair The Creation of Eve (1508 - 1512) by Michelangelo, showing Eve as blond

The Creation of Eve (1508 - 1512) by Michelangelo, showing Eve as blond

Early twentieth-century racism

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, blond hair, blue eyes, a tall stature, a long head, and an angled nose were deemed by scientific racists as hallmarks of the so-called "master race".[119][120] In the nineteenth century, this race was usually referred to as the "Germanic race",[119] but after the turn of the twentieth century, it came to be more commonly known as the "Nordic race".[119] German and Scandinavian scientists and academics throughout the early part of the twentieth century studied racial typology to the point of obsession[121] and debated the features of the Nordic race extensively.[121]

In the 1920s, the eugenicist Eugen Fischer invented the Fischer hair color table (Fischer Haarfarbentafel) to scientifically document hair color, which consisted of twenty-six bundles of cellulose fiber coated in non-fading colors attached to a palette and labeled with numbers.[122] Lighter colors were given higher numbers and darker ones were given lower numbers, with the distinction between "blond" and "brown" being set between seven and eight.[123] Fischer was a passionate supporter of Nazi eugenics and warned that miscegenation would result in the deterioration of modern civilization.[124] Dispute over the exact distinction between blond and brown hair was a heated debate among Norwegian anthropologists during this period,[125] with Halfdan Bryn arguing that the distinction should instead be set between six and seven.[126]

By the end of the 1920s, the International Federation of Eugenics Organizations (IFEO), the leading international eugenics organization, became increasingly dominated by proponents of the racial hygiene movement,[127] who sought to turn the organization into "Blond International", which would be "aimed at the purification and propagation of the Nordic race."[127] After the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933, racial anthropology based on the ideas of genetic superiority and racial psychology "became increasingly hegemonic in Germany."[127] The Nazis revered blond hair as a quality of the herrenrasse ("master race").[120]

The idea of racial superiority, which once dominated the field of anthropology, has now been completely and unanimously rejected by modern scientists.[128] Modern scientists have also rejected the assertions and beliefs of pre-World War II racialists.[129] Classification of race based on physical characteristics such as hair color is seen as a "flawed, pseudo-scientific relic of the past."[128] Many modern scientists dispute whether the concept of "race" is even a useful classification for human beings at all.[129]

Modern cultural stereotypes

Sexuality

In contemporary popular culture, blonde women are stereotyped as being more sexually attractive to men than women with other hair colors.[93] For example, Anita Loos popularized this idea in her 1925 novel Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.[93] Some women have reported they feel other people expect them to be more fun-loving after having lightened their hair.[93]

_(14577821128).jpg)

Madonna popularized the short bleached blond haircut after the release of her third studio album, True Blue, and influenced both the 1980s fashion scene as well as many future female musicians like Christina Aguilera, Lady Gaga, and Miley Cyrus.[130]

Intelligence

.jpg)

Originating in Europe, the "blonde stereotype" is also associated with being less serious or less intelligent.[93] Blonde jokes are a class of jokes based on the stereotype of blonde women as unintelligent.[93][131] In Brazil, this extends to blonde women being looked down, as reflected in sexist jokes, as also sexually licentious.[132] It is believed the originator of the dumb blonde was an eighteenth-century blonde French prostitute named Rosalie Duthé whose reputation of being beautiful but dumb inspired a play about her called Les Curiosites de la Foire (Paris 1775).[93] Blonde actresses have contributed to this perception; some of them include Marilyn Monroe, Judy Holliday, Jayne Mansfield, and Goldie Hawn during her time at Laugh-In.[93]

The British filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock preferred to cast blonde women for major roles in his films as he believed that the audience would suspect them the least, comparing them to "virgin snow that shows up the bloody footprints", hence the term Hitchcock blonde.[133] This stereotype has become so ingrained it has spawned counter-narratives, such as in the 2001 film Legally Blonde in which Elle Woods, played by Reese Witherspoon, succeeds at Harvard despite biases against her beauty and blond hair.[93]

In the 1950s, the American actress Marilyn Monroe's screen persona centered on her blond hair and the stereotypes associated with it, especially dumbness, naïveté, sexual availability and artificiality.[134] She often used a breathy, childish voice in her films, and in interviews gave the impression that everything she said was "utterly innocent and uncalculated", parodying herself with double entendres that came to be known as "Monroeisms".[135] For example, when she was asked what she had on in the 1949 nude photo shoot, she replied, "I had the radio on".[136] Monroe often wore white to emphasize her blondness, and drew attention by wearing revealing outfits that showed off her figure.[137] Although Monroe's typecast screen persona as a dim-witted but sexually attractive blonde was a carefully crafted act, audiences and film critics believed it to be her real personality and did not realize that she was only acting.[138]

The notion that blonds are less intelligent is not grounded in fact. A 2016 study of 10,878 Americans found that both women and men with natural blond hair had IQ scores similar to the average IQ of non-blond white Americans, and that white women with natural blond hair in fact had a higher average IQ score (103.2) than white women with brown hair (102.7), red hair (101.2), or black hair (100.5). Although many consider blonde jokes to be harmless, the author of the study stated the stereotype can have serious negative effects on hiring, promotion and other social experiences.[139][140] Rhiannon Williams of The Telegraph writes that dumb blonde jokes are "one of the last 'acceptable' forms of prejudice".[141]

See also

- Science

- Society

References

- ↑ "blonde|blond, adj. and n.". OED Online. March 2012. Oxford University Press. Web. 17 May 2012.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Blond (Adj.)." Online Etymology Dictionary. Web. Archived 2014-08-01 at the Wayback Machine. 17 May 2012.

- ↑ Origin of "blonde" Archived 2008-10-09 at the Wayback Machine., from Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ "5. Gender: Sexist Language and Assumptions § 2. blond / brunet". The American Heritage Book of English Usage. A Practical and Authoritative Guide to Contemporary English. Bartleby.com. 1996. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "blonde, blond, a. and n." The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 5 Aug. 2010.

- ↑ Penny cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, s.v. Albinos. Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain, 1833).

- ↑ "blonde, blond, a. and n." The Oxford English Dictionary. June 2006 [draft editions]. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 5 Aug. 2010

- ↑ "brunet, a. and n." The Oxford English Dictionary. June 2006 [draft editions]. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 5 Aug. 2010

- ↑ "brunette, n. and a." The Oxford English Dictionary. June 2006 [draft editions]. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 5 Aug. 2010.

- ↑ "blonde, blond, a. and n." The Oxford English Dictionary. Additions Series 1997. OED Online. Oxford University Press. 5 Aug. 2010.

- ↑ "Ash-blond". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2009-04-24.

- ↑ "Peroxide blond". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16.

- ↑ "Flaxen". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.). Yahoo! Education. 2000. Archived from the original on 2007-05-12. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Flaxen". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2009-04-24.

- ↑ "Dirty blond". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16.

- ↑ "Dishwater blonde". Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31.

- ↑ "Platinum blonde". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29.

- ↑ "Towhead". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.). Yahoo! Education. 2000. Archived from the original on 2008-06-26. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Towhead". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2009-04-24.

- ↑ "Sandy". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.). Yahoo! Education. 2000. Archived from the original on 2005-04-10. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Sandy". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2009-04-22.

- ↑ "Strawberry blond". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fourth ed.). Yahoo! Education. 2000. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ Nenarokoff-Van Burek, Anne (2013). Ariadne's Thread: The Women in My Family. FriesenPress. ISBN 9781460207192. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ Davydov, Denis Vasilʹevič (1999). Troubetzkoy, Gregory, ed. In the Service of the Tsar Against Napoleon: The Memoirs of Denis Davidov, 1806-1814. Greenhill Books/Lionel Leventhal, Limited. ISBN 9781853673733. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ Sutherland, Daniel E. (March 1, 2000). The Expansion of Everyday Life, 1860-1876. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 9781610751452. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ Browne, Ray Broadus; Kreiser, Lawrence A. (January 1, 2003). The Civil War and Reconstruction. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313313257. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ France, Anatole (2010). Works of Anatole France. MobileReference. ISBN 9781607785422. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Cavegirls were first blondes to have fun" Archived 2006-05-13 at the Wayback Machine., from The Times. Note, the end of the Times article reiterates the disappearing blonde gene hoax; the online version replaced it with a rebuttal.

- ↑ Dobson, Roger; Taher, Abul (2006-02-26). "A corrected version of "Cavegirls were first blondes to have fun"". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ Robins, Ashley H. Biological Perspectives on Human Pigmentation. Cambridge University Press, 1991, pp. 195–208.

- 1 2 Abstract: "European hair and eye colour: A case of frequency-dependent sexual selection?" from Evolution and Human Behavior, Volume 27, Issue 2, Pages 85-103 (March 2006)

- ↑ "Frost: Why Do Europeans Have So Many Hair and Eye Colors?". cogweb.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-08-25. Retrieved 2016-08-21.

- ↑ Mathieson et al., The Genomic History Of Southeastern Europe, bioRxiv, (19 September 2017), doi:10.1101/135616 = Nature vol. 555, 197–203 (8 March 2018), doi:10.1038/nature25778.

- 1 2 Skoglund, P.; Malmström, H. "Genomic diversity and admixture differs for Stone-Age Scandinavian foragers and farmers". Science. 344: 747–750. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..747S. doi:10.1126/science.1253448.

- 1 2 Wilde, Sandra; Timpson, Adrian. "Direct evidence for positive selection of skin, hair, and eye pigmentation in Europeans during the last 5,000 years". PNAS. 111: 4832–4837. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4832W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1316513111. PMC 3977302.

- 1 2 Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I. "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522: 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- 1 2 3 4 Kenny, Eimear E.; Timpson, Nicholas J. (4 May 2012). "Melanesian Blond Hair Is Caused by an Amino Acid Change in TYRP1". Science. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- 1 2 Corbyn, Zoë (3 May 2012). "Blonde hair evolved more than once". Nature.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012.

- 1 2 Ridley, Matt. Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature. Published by HarperCollins, 2nd ed. 2003, pp. 293–294.

- 1 2 3 Davies 2011, p. 73.

- 1 2 Russell-Cole, Wilson & Hall 2013, p. 52.

- ↑ Russell-Cole, Wilson & Hall 2013, pp. 51-53.

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza, L., Menozzi, P. and Piazza, A. (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Coon, Carleton S. The Races of Europe.

France as a whole finds but 4 per cent of black and near-black hair color, 23 per cent of dark brown, 43 per cent of medium brown, 14 per cent of light brown, 12 per cent of various degrees of blond, and some 4 per cent of reddish-brown and red. (...)

The regional distribution of hair color in France follows closely that of stature. Although the position of the French in regard to hair pigmentation is intermediate between blond and black, the diagonal line from Mont St. Michel to Orleans, Lyons, and the Italian border divides the country into a northeastern quadrant, in which the hair is somewhat lighter than medium, and a southwestern, in which it is somewhat darker. High ratios of black and very dark brown hair are found not in the typically Alpine country, but along the slope of the Pyrenees, in Catalan-speaking country, and on the Mediterranean seacoast. Blond hair is commonest along the Channel, in regions settled by Saxons and Normans, in Burgundy and the country bordering Switzerland, and down the course of the Rhône. In northern France it seems to follow upstream the rivers which empty into the Channel. The hair color of the departments occupied by Flemish speakers, and of others directly across the Channel from England in Normandy, seems to be nearly as light as that in the southern English counties; the coastal cantons of Brittany are lighter than the inland ones, and approximate a Cornish condition. In the same way, the northeastern French departments are probably as light-haired as some of the provinces of southern Germany.|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "5 millions de blondes en France, dont 50% de fausses". ladepeche.fr. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Tamagnini Eusebio: "A Pigmentacao dos Portugueses". Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra. Instituto de Antropologia Portuguesa, 1936. Contribuicoes para o Estudo da Antropologia Portuguesa. Vol. VI, no. 2, 1936 pp. 121–197.

- ↑ Mendes Correa: American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Vol 2, 1919.

- ↑ Coon, Carleton S. The Races of Europe. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

In Spain, as a whole, some 29 per cent of the male population has black hair, some 68 per cent dark brown, while traces of blondism are visible in 17 per cent. (...) As in southern Spain, the skin color is evenly divided between a light brown, 45 per cent, and brunet-white, 45 per cent, while pinkish-white skins are found in only one-tenth of the population. Again as in Spain, the prevailing hair color is dark brown, which amounts to 68 per cent of the total; blond and red hair is limited to 2 per cent.

- ↑ Livi, Ridolfo (1921). Antropometria Militare. Risultati Ottenuti Dallo Spoglio Dei Fogli Sanitarii Dei Militari Dello Classi 1859-63. Turin: Nabu Press.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Biasutti, Renato (1941). Razze e popoli della Terra. Turin: Union Tipografico-Editrice.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-19. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ↑ "(Chapter XI, section 13) Eastern Barbary, Algeria and Tunisia". SNPA. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ↑ C. Wilfred Griggs, "Excavating a Christian Cemetery Near Selia, in the Fayum Region of Egypt" Archived 2015-06-04 at the Wayback Machine., in Excavations at Seila, Egypt, ed. C. Wilfred Griggs, (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 74–84.

- ↑ "Egyptian Cemetery May Contain a Million Mummies History" Archived 2015-03-26 at the Wayback Machine., December 19, 2014

- ↑ Gray, John (1977), The World of Hair, A Scientific Companion. Macmillan Press Limited

- 1 2 3 Wilde 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Allentoft 2015.

- 1 2 3 Haak 2015.

- ↑ Keyser, Christine; Sikora, Caroline. "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Springer (journal). 522: 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507.

- ↑ Shoumatoff, Nicholas; Shoumatoff, Nina (2000). Around the Roof of the World. University of Michigan Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-472-08669-3.

- ↑ Vishnevsky, Anatoly. (15 August 2000). "Replacement Migration: Is it a solution for Russia?" (PDF). Expert Group Meeting on Policy Responses to Population Ageing and Population Decline /UN/POP/PRA/2000/14. United Nations Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. pp. 6,10.

- ↑ Gene Pool and Gene Geography of Population: Vol. 1. Nauka. 2000. ISBN 5020258237.

- ↑ Balaresque, Patricia; Bowden, Georgina R.; Adams, Susan M.; Leung, Ho-Yee; King, Turi E.; et al. (2010). Penny, David, ed. "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for European Paternal Lineages". PLOS Biology. Public Library of Science. 8 (1): e1000285. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285. PMC 2799514. PMID 20087410. Archived from the original on August 5, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ "The results of the national population census in 2009". Agency of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 12 November 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ↑ Flynn, Moya (1994). Migrant resettlement in the Russian Federation: Reconstructing homes and homelands. ISBN 1843311178.

- ↑ Ramet, S. Petra (1993). Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521416436.

- ↑ Robert Greenall, "Russians left behind in Central Asia" Archived 2013-09-11 at the Wayback Machine., BBC News, 23 November 2005

- ↑ Quinonez, Ernesto (2003-06-19). "Y Tu Black Mama Tambien". Archived from the original on 2008-10-27. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ "Washington Post: Breaking News, World, US, DC News & Analysis". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "LatinoLA - Forum :: Blonde, Blue-Eyed, Euro-Cute Latinos on Spanish TV". LatinoLA. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Latinos not reflected on Spanish TV". www.vidadeoro.com. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "What are Telenovelas? – Hispanic Culture". bellaonline.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Racial Bias Charged On Spanish-language Tv". sun-sentinel.com. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ ":: BlackElectorate.com ::". www.blackelectorate.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Jones, Vanessa E. (2004-08-19). "Pride or Prejudice?". Boston.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-12. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ↑ POV (23 January 1999). "Film Description - Corpus - POV - PBS". pbs.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Pitman 2003, p. 12.

- 1 2 Myres, John Linton (1967). Who were the Greeks?, pp. 192-199. University of California Press.

- ↑ Pitman 2003, pp. 9-10.

- 1 2 3 4 Pitman 2003, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Stieber 2004, pp. 66-68.

- ↑ Stieber 2004, p. 156.

- ↑ Eddy 1977, pp. 107–11.

- 1 2 3 Marshall 2006, p. 148.

- 1 2 Olson 1992, pp. 304–319.

- ↑ Pitman 2003, pp. 9-10, 14-15.

- ↑ Pitman 2003, pp. 9-11, 14-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pitman 2003, p. 11.

- ↑ Fletcher 2008, pp. 87, 246-247, see image plates and captions.

- ↑ Grant 1992, p. 5.

- ↑ Olga Palagia (2000). "Hephaestion's Pyre and the Royal Hunt of Alexander," in A.B. Bosworth and E.J. Baynham (eds), Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198152873, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 Sherrow 2006, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sherrow 2006, p. 149.

- ↑ Victoria Sherrow, For Appearance' Sake: The Historical Encyclopedia of Good Looks, Beauty, and Grooming, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 136, Google Books

- ↑ " (Francis Owen,The Germanic people; their Origin Expansion & Culture", 1993 Barnes & Noble Books ISBN 0-88029-579-1, page 49.)

- ↑ "Juvenal, Satires, book 2, Satura VI". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Maurus Servius Honoratus, Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil, SERVII GRAMMATICI IN VERGILII AENEIDOS LIBRVM QUARTVM COMMENTARIVS, line 698". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Michael Grant (1994). The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10754-7, pp 27-28.

- ↑ Colin Wells (2004) [1984, 1992]. The Roman Empire. Second Edition (sixth reprint edition). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-77770-0, p 255.

- ↑ "P. Vergilius Maro, Aeneid, Book 8, line 630". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Cornelius Tacitus, Germany and its Tribes, chapter 4". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ "Ammianus Marcellinus, Rerum Gestarum, Book XV, chapter 12, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, Adrian (2000). Roman Warfare. Edited by John Keegan. Cassell, p. 126.

- ↑ Rüger, C. (2004) [1996]. "Germany". In Alan K. Bowman; Edward Champlin; Andrew Lintott. The Cambridge Ancient History: X, The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C. - A.D. 69. 10 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 523–526. ISBN 0-521-26430-8.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annales I.78

- ↑ Rüger, C. (2004) [1996]. "Germany". In Alan K. Bowman; Edward Champlin; Andrew Lintott. The Cambridge Ancient History: X, The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C. - A.D. 69. 10 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 527–528. ISBN 0-521-26430-8.

- ↑ Wolfram, Herwig (1997) [1990]. The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. Translated by Thomas Dunlap. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08511-6. p. 65.

- 1 2 James B. Minahan (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: a Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Westport and London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-30984-1, p. 278.

- ↑ J. Carson Webster, The Labors of the Months in Antique and Mediaeval Art to the End of the Twelfth Century, Studies in the Humanities 4 (Northwestern University Press, 1938), p. 128. In the collections of the Hermitage Museum.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Milliken 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1965). Gods and Myths of Northern Europe, page 84. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- ↑ Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures, "Golden Hair", p194. ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ↑ Milliken 2012, pp. 41-43.

- ↑ Milliken 2012, p. 100.

- ↑ Schiller 1971, pp. 154–158.

- 1 2 3 Milliken 2012, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Six 2014, pp. 75-76.

- ↑ Eric V. Alvarez (2002). "Cosmetics in Medieval and Renaissance Spain", in Janet Pérez and Maureen Ihrie (eds), The Feminist Encyclopedia of Spanish Literature, A-M. 153-155. Westport and London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29346-5, p. 154

- 1 2 3 4 Kyllingstad 2014, p. xiii.

- 1 2 3 Lichtman 2012, p. 120.

- 1 2 Kyllingstad 2014, pp. xiii-xiv.

- ↑ Lichtman 2012, p. 176.

- ↑ Lichtman 2012, pp. 176-177.

- ↑ Lichtman 2012, pp. 111-112.

- ↑ Lichtman 2012, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ Lichtman 2012, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 Kyllingstad 2014, p. 112.

- 1 2 Kyllingstad 2014, p. xiv.

- 1 2 Kyllingstad 2014, pp. xiv-xv.

- ↑ "Madonna's Influence on Fashion". Archived from the original on 2018-02-26.

- ↑ Thomas 1997, pp. 277–313.

- ↑ Revista Anagrama, Universidade de São Paulo, Stereotypes of women in blonde jokes pp. 6-8 Archived 2015-11-21 at the Wayback Machine., version 1, edition 2, 2007

- ↑ Allen, Richard (2007). Hitchcock's Romantic Irony. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13574-0.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, pp. 21–26, 181–185.

- ↑ Dyer 1986, pp. 33–34; Churchwell 2004, pp. 25, 57–58; Banner 2012, p. 185; Hall 2006, p. 489.

- ↑ Banner 2012, p. 194.

- ↑ Churchwell 2004, p. 25; Banner 2012, pp. 246–250.

- ↑ Banner 2012, pp. 273–276.

- ↑ http://www.health.com/mind-body/scientists-debunk-dumb-blonde-myth

- ↑ https://news.osu.edu/news/2016/03/21/blond-intelligence/

- ↑ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/womens-life/10436508/Why-I-hate-dumb-blonde-jokes.html

Bibliography

- Banner, Lois (2012), Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox, Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-1-4088-3133-5

- Churchwell, Sarah (2004), The Many Lives of Marilyn Monroe, Granta Books, ISBN 978-0-312-42565-4

- Davies, Christie (2011), Jokes and Targets, Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-22302-9

- Dyer, Richard (1986), Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-31026-1

- Eddy, Samuel (1977), "The Gold in the Athena Parthenos", American Journal of Archaeology, 81 (1): 107–11, doi:10.2307/503656, JSTOR 503656

- Fletcher, Joann (2008), Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend, New York: Harper, ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7.

- Grant, Michael (1992) [1972], Cleopatra, Edison, NJ: Barnes and Noble Books, ISBN 978-0880297257 .

- Hall, Susan G. (2006), American Icons: An Encyclopedia of the People, Places, and Things that Have Shaped Our Culture, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-98429-8

- Kyllingstad, Jon Røyne (2014), Measuring the Master Race: Physical Anthropology in Norway, 1890-1945, Cambridge, England: Open Book Publishers, ISBN 978-1-909254-57-2

- Lichtman, Loy (2012), "Reflection 10: Pamela Anderson, Durer and Herrenvolk", in Ryan, Maureen, Reflections on Learning, Life and Work: Completing Doctoral Studies in Mid and Later Life and Career, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, Boston, Massachusetts, and Tapei, Taiwan: Sense Publishers, ISBN 978-94-6209-025-5

- Marshall, C. W. (2006), The Stagecraft and Performance of Roman Comedy, Cambridge, England: Cambirdge Unviversity Press, ISBN 978-0-521-86161-8

- Milliken, Roberta (2012), Ambiguous Locks: An Iconology of Hair in Medieval Art and Literature, Jefferson, North Carolina and London, England: MacFarlane & Company, Inc., Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7864-4870-8

- Olson, S. Douglas (January 1992), "Names and Naming in Aristophanic Comedy", The Classical Quarterly, The Classical Association, 42 (2): 304–319, JSTOR 639409

- Pitman, Joanna (2003), On Blondes, New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury, ISBN 1-58234-402-7

- Russell-Cole, Kathy; Wilson, Midge; Hall, Ronald E. (2013) [1992], The Color Complex: The Politics of Skin Color in a New Millennium, New York City, New York: Anchor Books, A Division of Random House, Inc., ISBN 978-0-307-74423-4

- Schiller, Gertud (1971), Iconography of Christian Art, I, London, England: Lund Humphries, ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- Sherrow, Victoria (2006), "Hair color", Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History, Westport, Connecticut and London, England, ISBN 0-313-33145-6

- Six, Abigail Lee (2014), "Chapter Five: Spinning Straw into Gold: Blond Hair and the Autobiographical Illusion in the Fiction of Esther Tusquets", in Molinaro, Nina L.; Pertusa-Seva, Inmaculada, Esther Tusquets: Scholarly Correspondences, Cambridge, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4438-5908-0

- Stieber, Mary (2004), The Poetics of Appearance in the Attic Korai, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, ISBN 9780292701809

- Thomas, Jeannie B. (1997). "Dumb Blondes, Dan Quayle, and Hillary Clinton: Gender, Sexuality, and Stupidity in Jokes". The Journal of American Folklore. 110 (437): 277–313. doi:10.2307/541162.

External links

| Look up blond in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blond hair. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blond hair in art. |