Mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA)[3] is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is only a small portion of the DNA in a eukaryotic cell; most of the DNA can be found in the cell nucleus and, in plants and algae, also in plastids such as chloroplasts.

In humans, the 16,569 base pairs of mitochondrial DNA encode for only 37 genes.[4] Human mitochondrial DNA was the first significant part of the human genome to be sequenced. In most species, including humans, mtDNA is inherited solely from the mother.[5][6]

Since animal mtDNA evolves faster than nuclear genetic markers,[7][8][9] it represents a mainstay of phylogenetics and evolutionary biology. It also permits an examination of the relatedness of populations, and so has become important in anthropology and biogeography.

Origin

Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA are thought to be of separate evolutionary origin, with the mtDNA being derived from the circular genomes of the bacteria that were engulfed by the early ancestors of today's eukaryotic cells. This theory is called the endosymbiotic theory. Each mitochondrion is estimated to contain 2–10 mtDNA copies.[10] In the cells of extant organisms, the vast majority of the proteins present in the mitochondria (numbering approximately 1500 different types in mammals) are coded for by nuclear DNA, but the genes for some, if not most, of them are thought to have originally been of bacterial origin, having since been transferred to the eukaryotic nucleus during evolution.[11]

The reasons why mitochondria have retained some genes are debated. The existence in some species of mitochondrion-derived organelles lacking a genome[12] suggests that complete gene loss is possible, and transferring mitochondrial genes to the nucleus has several advantages.[13] The difficulty of targeting remotely-produced hydrophobic protein products to the mitochondrion is one hypothesis for why some genes are retained in mtDNA;[14] colocalisation for redox regulation is another, citing the desirability of localised control over mitochondrial machinery.[15] Recent analysis of a wide range of mtDNA genomes suggests that both these features may dictate mitochondrial gene retention.[11]

Mitochondrial inheritance

In most multicellular organisms, mtDNA is inherited from the mother (maternally inherited). Mechanisms for this include simple dilution (an egg contains on average 200,000 mtDNA molecules, whereas a healthy human sperm was reported to contain on average 5 molecules[16][17] ), degradation of sperm mtDNA in the male genital tract, in the fertilized egg, and, at least in a few organisms, failure of sperm mtDNA to enter the egg. Whatever the mechanism, this single parent (uniparental inheritance) pattern of mtDNA inheritance is found in most animals, most plants and in fungi as well.

Female inheritance

In sexual reproduction, mitochondria are normally inherited exclusively from the mother; the mitochondria in mammalian sperm are usually destroyed by the egg cell after fertilization. Also, most mitochondria are present at the base of the sperm's tail, which is used for propelling the sperm cells; sometimes the tail is lost during fertilization. In 1999 it was reported that paternal sperm mitochondria (containing mtDNA) are marked with ubiquitin to select them for later destruction inside the embryo.[18] Some in vitro fertilization techniques, particularly injecting a sperm into an oocyte, may interfere with this.

The fact that mitochondrial DNA is maternally inherited enables genealogical researchers to trace maternal lineage far back in time. (Y-chromosomal DNA, paternally inherited, is used in an analogous way to determine the patrilineal history.) This is usually accomplished on human mitochondrial DNA by sequencing the hypervariable control regions (HVR1 or HVR2), and sometimes the complete molecule of the mitochondrial DNA, as a genealogical DNA test.[19] HVR1, for example, consists of about 440 base pairs. These 440 base pairs are then compared to the control regions of other individuals (either specific people or subjects in a database) to determine maternal lineage. Most often, the comparison is made to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence. Vilà et al. have published studies tracing the matrilineal descent of domestic dogs to wolves.[20] The concept of the Mitochondrial Eve is based on the same type of analysis, attempting to discover the origin of humanity by tracking the lineage back in time.

mtDNA is highly conserved, and its relatively slow mutation rates (compared to other DNA regions such as microsatellites) make it useful for studying the evolutionary relationships—phylogeny—of organisms. Biologists can determine and then compare mtDNA sequences among different species and use the comparisons to build an evolutionary tree for the species examined. However, due to the slow mutation rates it experiences, it is often hard to distinguish between closely related species to any large degree, so other methods of analysis must be used.

The mitochondrial bottleneck

Entities undergoing uniparental inheritance and with little to no recombination may be expected to be subject to Muller's ratchet, the accumulation of deleterious mutations until functionality is lost. Animal populations of mitochondria avoid this buildup through a developmental process known as the mtDNA bottleneck. The bottleneck exploits stochastic processes in the cell to increase in the cell-to-cell variability in mutant load as an organism develops: a single egg cell with some proportion of mutant mtDNA thus produces an embryo where different cells have different mutant loads. Cell-level selection may then act to remove those cells with more mutant mtDNA, leading to a stabilisation or reduction in mutant load between generations. The mechanism underlying the bottleneck is debated,[21][22][23][24] with a recent mathematical and experimental metastudy providing evidence for a combination of random partitioning of mtDNAs at cell divisions and random turnover of mtDNA molecules within the cell.[25]

Male inheritance

Doubly uniparental inheritance of mtDNA is observed in bivalve mollusks. In those species, females have only one type of mtDNA (F), whereas males have F type mtDNA in their somatic cells, but M type of mtDNA (which can be as much as 30% divergent) in germline cells.[26] Paternally inherited mitochondria have additionally been reported in some insects such as fruit flies,[27][28] honeybees,[29] and periodical cicadas.[30]

Male mitochondrial inheritance was recently discovered in Plymouth Rock chickens.[31] Evidence supports rare instances of male mitochondrial inheritance in some mammals as well. Specifically, documented occurrences exist for mice,[32][33] where the male-inherited mitochondria were subsequently rejected. It has also been found in sheep,[34] and in cloned cattle.[35] It has been found in a single case in a human male.[36]

Although many of these cases involve cloned embryos or subsequent rejection of the paternal mitochondria, others document in vivo inheritance and persistence under lab conditions.

Mitochondrial donation

An IVF technique known as mitochondrial donation or mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT) results in offspring containing mtDNA from a donor female, and nuclear DNA from the mother and father. In the spindle transfer procedure, the nucleus of an egg is inserted into the cytoplasm of an egg from a donor female which has had its nucleus removed, but still contains the donor female's mtDNA. The composite egg is then fertilized with the male's sperm. The procedure is used when a woman with genetically defective mitochondria wishes to procreate and produce offspring with healthy mitochondria.[37] The first known child to be born as a result of mitochondrial donation was a boy born to a Jordanian couple in Mexico on 6 April 2016.[38]

Structure

Circular versus linear

In most multicellular organisms, the mtDNA – or mitogenome – is organized as a circular, covalently closed, double-stranded DNA. But in many unicellular (e.g. the ciliate Tetrahymena or the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) and in rare cases also in multicellular organisms (e.g. in some species of Cnidaria) the mtDNA is found as linearly organized DNA. Most of these linear mtDNAs possess telomerase-independent telomeres (i.e. the ends of the linear DNA) with different modes of replication, which have made them interesting objects of research, as many of these unicellular organisms with linear mtDNA are known pathogens.[39]

In mammals

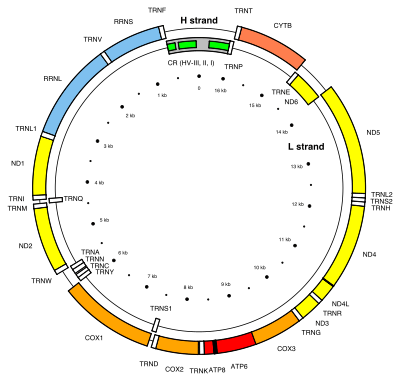

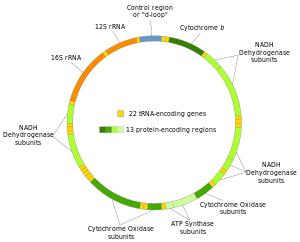

For human mitochondrial DNA (and probably for that of metazoans in general), 100–10,000 separate copies of mtDNA are usually present per somatic cell (egg and sperm cells are exceptions). In mammals, each double-stranded circular mtDNA molecule consists of 15,000–17,000[40] base pairs. The two strands of mtDNA are differentiated by their nucleotide content, with a guanine-rich strand referred to as the heavy strand (or H-strand) and a cytosine-rich strand referred to as the light strand (or L-strand). However, confusion of labeling of these strands is widespread, and appears to originate with a identification of the majority coding strand as the heavy in one influential article in 1999.[41] The light strand encodes 28 genes, and the heavy strand encodes 9 genes for a total of 37 genes.[4] Of the 37 genes, 13 are for proteins (polypeptides), 22 are for transfer RNA (tRNA) and two are for the small and large subunits of ribosomal RNA (rRNA).[42] The human mitogenome contains overlapping genes (ATP8 and ATP6 as well as ND4L and ND4: see the human mitochondrial genome map), a feature that is rare in animal genomes. The 37-gene pattern is also seen among most metazoans, although in some cases one or more of these genes is absent and the mtDNA size range is greater.

| Gene | Type | Product | Positions in the mitogenome |

Strand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT-ATP8 | protein coding | ATP synthase, Fo subunit 8 (complex V) | 08,366–08,572 (overlap with MT-ATP6) | L |

| MT-ATP6 | protein coding | ATP synthase, Fo subunit 6 (complex V) | 08,527–09,207 (overlap with MT-ATP8) | L |

| MT-CO1 | protein coding | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit 1 (complex IV) | 05,904–07,445 | L |

| MT-CO2 | protein coding | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit 2 (complex IV) | 07,586–08,269 | L |

| MT-CO3 | protein coding | Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit 3 (complex IV) | 09,207–09,990 | L |

| MT-CYB | protein coding | Cytochrome b (complex III) | 14,747–15,887 | L |

| MT-ND1 | protein coding | NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 1 (complex I) | 03,307–04,262 | L |

| MT-ND2 | protein coding | NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 2 (complex I) | 04,470–05,511 | L |

| MT-ND3 | protein coding | NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 3 (complex I) | 10,059–10,404 | L |

| MT-ND4L | protein coding | NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 4L (complex I) | 10,470–10,766 (overlap with MT-ND4) | L |

| MT-ND4 | protein coding | NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 4 (complex I) | 10,760–12,137 (overlap with MT-ND4L) | L |

| MT-ND5 | protein coding | NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 5 (complex I) | 12,337–14,148 | L |

| MT-ND6 | protein coding | NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 6 (complex I) | 14,149–14,673 | H |

| MT-RNR2 | protein coding | Humanin | — | — |

| MT-TA | transfer RNA | tRNA-Alanine (Ala or A) | 05,587–05,655 | H |

| MT-TR | transfer RNA | tRNA-Arginine (Arg or R) | 10,405–10,469 | L |

| MT-TN | transfer RNA | tRNA-Asparagine (Asn or N) | 05,657–05,729 | H |

| MT-TD | transfer RNA | tRNA-Aspartic acid (Asp or D) | 07,518–07,585 | L |

| MT-TC | transfer RNA | tRNA-Cysteine (Cys or C) | 05,761–05,826 | H |

| MT-TE | transfer RNA | tRNA-Glutamic acid (Glu or E) | 14,674–14,742 | H |

| MT-TQ | transfer RNA | tRNA-Glutamine (Gln or Q) | 04,329–04,400 | H |

| MT-TG | transfer RNA | tRNA-Glycine (Gly or G) | 09,991–10,058 | L |

| MT-TH | transfer RNA | tRNA-Histidine (His or H) | 12,138–12,206 | L |

| MT-TI | transfer RNA | tRNA-Isoleucine (Ile or I) | 04,263–04,331 | L |

| MT-TL1 | transfer RNA | tRNA-Leucine (Leu-UUR or L) | 03,230–03,304 | L |

| MT-TL2 | transfer RNA | tRNA-Leucine (Leu-CUN or L) | 12,266–12,336 | L |

| MT-TK | transfer RNA | tRNA-Lysine (Lys or K) | 08,295–08,364 | L |

| MT-TM | transfer RNA | tRNA-Methionine (Met or M) | 04,402–04,469 | L |

| MT-TF | transfer RNA | tRNA-Phenylalanine (Phe or F) | 00,577–00,647 | L |

| MT-TP | transfer RNA | tRNA-Proline (Pro or P) | 15,956–16,023 | H |

| MT-TS1 | transfer RNA | tRNA-Serine (Ser-UCN or S) | 07,446–07,514 | H |

| MT-TS2 | transfer RNA | tRNA-Serine (Ser-AGY or S) | 12,207–12,265 | L |

| MT-TT | transfer RNA | tRNA-Threonine (Thr or T) | 15,888–15,953 | L |

| MT-TW | transfer RNA | tRNA-Tryptophan (Trp or W) | 05,512–05,579 | L |

| MT-TY | transfer RNA | tRNA-Tyrosine (Tyr or Y) | 05,826–05,891 | H |

| MT-TV | transfer RNA | tRNA-Valine (Val or V) | 01,602–01,670 | L |

| MT-RNR1 | ribosomal RNA | Small subunit : SSU (12S) | 00,648–01,601 | L |

| MT-RNR2 | ribosomal RNA | Large subunit : LSU (16S) | 01,671–03,229 | L |

In plants

Great variation in mtDNA gene content and size exists among fungi and plants, although there appears to be a core subset of genes that are present in all eukaryotes (except for the few that have no mitochondria at all).[11] Some plant species have enormous mitochondrial genomes, with Silene conica mtDNA containing as many as 11,300,000 base pairs.[43] Surprisingly, even those huge mtDNAs contain the same number and kinds of genes as related plants with much smaller mtDNAs.[44] The genome of the mitochondrion of the cucumber (Cucumis sativus) consists of three circular chromosomes (lengths 1556, 84 and 45 kilobases), which are entirely or largely autonomous with regard to their replication.[45]

In protists

The smallest mitochondrial genome sequenced to date is the 5,967 bp mtDNA of the parasite Plasmodium falciparum.[46][47]

Genome diversity

There are six main genome types found in mitochondrial genomes, classified by their structure (e.g. circular versus linear), size, presence of introns or plasmid like structures, and whether the genetic material is a singular molecule or collection of homogeneous or heterogeneous molecules.[48]

Animals

There is only one mitochondrial genome type found in animal cells. This genome usually contains one circular molecule with between 11–28 kbp of genetic material (type 1).[48]

Plants and fungi

There are three different genome types found in plants and fungi. The first type is a circular genome that has introns (type 2) and may range from 19 to 1000 kbp in length. The second genome type is a circular genome (about 20–1000 kbp) that also has a plasmid-like structure (1 kb) (type 3). The final genome type that can be found in plant and fungi is a linear genome made up of homogeneous DNA molecules (type 5).

Protists

Protists contain the most diverse mitochondrial genomes, with five different types found in this kingdom. Type 2, type 3 and type 5 mentioned in the plant and fungal genomes also exists in some protist, as well as two unique genome types. The first of these is a heterogeneous collection of circular DNA molecules (type 4) and the final genome type found in protists is a heterogeneous collection of linear molecules (type 6). Genome types 4 and 6 both range from 1–200 kbp in size.

Endosymbiotic gene transfer, the process of genes that were coded in the mitochondrial genome being transferred to the cell's main genome likely explains why more complex organisms, such as humans, have smaller mitochondrial genomes than simpler organisms, such as protists.

| Genome Type[48] | Kingdom | Introns | Size | Shape | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Animal | No | 11–28 kbp | Circular | Single molecule |

| 2 | Fungi, Plant, Protista | Yes | 19–1000 kbp | Circular | Single molecule |

| 3 | Fungi, Plant, Protista | No | 20–1000 kbp | Circular | Large molecule and small plasmid like structures |

| 4 | Protista | No | 1–200 kbp | Circular | Heterogeneous group of molecules |

| 5 | Fungi, Plant, Protista | No | 1–200 kbp | Linear | Homogeneous group of molecules |

| 6 | Protista | No | 1–200 kbp | Linear | Heterogeneous group of molecules |

Replication

Mitochondrial DNA is replicated by the DNA polymerase gamma complex which is composed of a 140 kDa catalytic DNA polymerase encoded by the POLG gene and two 55 kDa accessory subunits encoded by the POLG2 gene.[49] The replisome machinery is formed by DNA polymerase, TWINKLE and mitochondrial SSB proteins. TWINKLE is a helicase, which unwinds short stretches of dsDNA in the 5′ to 3′ direction.[50] All these polypeptides are encoded in the nuclear genome.

During embryogenesis, replication of mtDNA is strictly down-regulated from the fertilized oocyte through the preimplantation embryo.[51] The resulting reduction in per-cell copy number of mtDNA plays a role in the mitochondrial bottleneck, exploiting cell-to-cell variability to ameliorate the inheritance of damaging mutations.[25] At the blastocyst stage, the onset of mtDNA replication is specific to the cells of the trophectoderm.[51] In contrast, the cells of the inner cell mass restrict mtDNA replication until they receive the signals to differentiate to specific cell types.[51]

Transcription

In animal mitochondria, each DNA strand is transcribed continuously and produces a polycistronic RNA molecule. Between most (but not all) protein-coding regions, tRNAs are present (see the human mitochondrial genome map). During transcription, the tRNAs acquire their characteristic L-shape that gets recognized and cleaved by specific enzymes. With the mitochondrial RNA processing, individual mRNA, rRNA, and tRNA sequences are released from the primary transcript.[52] Folded tRNAs therefore act as secondary structure punctuations.[53]

Mutations and disease

Susceptibility

The concept that mtDNA is particularly susceptible to reactive oxygen species generated by the respiratory chain due to its proximity remains controversial.[54] mtDNA does not accumulate any more oxidative base damage than nuclear DNA.[55] It has been reported that at least some types of oxidative DNA damage are repaired more efficiently in mitochondria than they are in the nucleus.[56] mtDNA is packaged with proteins which appear to be as protective as proteins of the nuclear chromatin.[57] Moreover, mitochondria evolved a unique mechanism which maintains mtDNA integrity through degradation of excessively damaged genomes followed by replication of intact/repaired mtDNA. This mechanism is not present in the nucleus and is enabled by multiple copies of mtDNA present in mitochondria [58] The outcome of mutation in mtDNA may be an alteration in the coding instructions for some proteins,[59] which may have an effect on organism metabolism and/or fitness.

Genetic illness

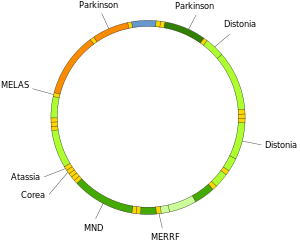

Mutations of mitochondrial DNA can lead to a number of illnesses including exercise intolerance and Kearns–Sayre syndrome (KSS), which causes a person to lose full function of heart, eye, and muscle movements. Some evidence suggests that they might be major contributors to the aging process and age-associated pathologies.[60] Particularly in the context of disease, the proportion of mutant mtDNA molecules in a cell is termed heteroplasmy. The within-cell and between-cell distributions of heteroplasmy dictate the onset and severity of disease [61] and are influenced by complicated stochastic processes within the cell and during development.[25][62]

Mutations in mitochondrial tRNAs can be responsible for severe diseases like the MELAS and MERRF syndromes.[63]

Mutations in nuclear genes that encode proteins that mitochondria use can also contribute to mitochondrial diseases. These diseases do not follow mitochondrial inheritance patterns, but instead follow Mendelian inheritance patterns.[64]

Use in disease diagnosis

Recently a mutation in mtDNA has been used to help diagnose prostate cancer in patients with negative prostate biopsy.[65][66]

Relationship with aging

Though the idea is controversial, some evidence suggests a link between aging and mitochondrial genome dysfunction.[67] In essence, mutations in mtDNA upset a careful balance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and enzymatic ROS scavenging (by enzymes like superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and others). However, some mutations that increase ROS production (e.g., by reducing antioxidant defenses) in worms increase, rather than decrease, their longevity.[54] Also, naked mole rats, rodents about the size of mice, live about eight times longer than mice despite having reduced, compared to mice, antioxidant defenses and increased oxidative damage to biomolecules.[68] Once, there was thought to be a positive feedback loop at work (a 'Vicious Cycle'); as mitochondrial DNA accumulates genetic damage caused by free radicals, the mitochondria lose function and leak free radicals into the cytosol. A decrease in mitochondrial function reduces overall metabolic efficiency.[69] However, this concept was conclusively disproved when it was demonstrated that mice, which were genetically altered to accumulate mtDNA mutations at accelerated rate do age prematurely, but their tissues do not produce more ROS as predicted by the 'Vicious Cycle' hypothesis.[70] Supporting a link between longevity and mitochondrial DNA, some studies have found correlations between biochemical properties of the mitochondrial DNA and the longevity of species.[71] Extensive research is being conducted to further investigate this link and methods to combat aging. Presently, gene therapy and nutraceutical supplementation are popular areas of ongoing research.[72][73] Bjelakovic et al. analyzed the results of 78 studies between 1977 and 2012, involving a total of 296,707 participants, and concluded that antioxidant supplements do not reduce all-cause mortality nor extend lifespan, while some of them, such as beta carotene, vitamin E, and higher doses of vitamin A, may actually increase mortality.[74]

Neurodegenerative diseases

Increased mtDNA damage is a feature of several neurodegenerative diseases.

The brains of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease have elevated levels of oxidative DNA damage in both nuclear DNA and mtDNA, but the mtDNA has approximately 10-fold higher levels than nuclear DNA.[75] It has been proposed that aged mitochondria is the critical factor in the origin of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease.[76]

In Huntington’s disease, mutant huntingtin protein causes mitochondria dysfunction involving inhibition of mitochondrial electron transport, higher levels of reactive oxygen species and increased oxidative stress.[77] Mutant huntingtin protein promotes oxidative damage to mtDNA, as well as nuclear DNA, that may contribute to Huntington’s disease pathology.[78]

The DNA oxidation product 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) is a well-established marker of oxidative DNA damage. In persons with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the enzymes that normally repair 8-oxoG DNA damages in the mtDNA of spinal motor neurons are impaired.[79] Thus oxidative damage to mtDNA of motor neurons may be a significant factor in the etiology of ALS.

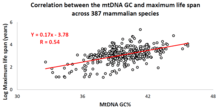

Correlation of the mtDNA base composition with animals lifespan

Over the past decade, an Israeli research group led by Professor Vadim Fraifeld has shown that extraordinarily strong and significant correlations exist between the mtDNA base composition and animal species-specific maximum life spans.[80][81][82] As demonstrated in their work, higher mtDNA guanine + cytosine content (GC%) strongly associates with longer maximum life spans across animal species. An additional astonishing observation is that the mtDNA GC% correlation with the maximum life spans is independent of the well-known correlation between animal species metabolic rate and maximum life spans. The mtDNA GC% and resting metabolic rate explain the differences in animal species maximum life spans in a multiplicative manner (i.e., species maximum life span = their mtDNA GC% * metabolic rate).[81] To support the scientific community in carrying out comparative analyses between mtDNA features and longevity across animals, a dedicated database was built named MitoAge.[83]

Relationship with non-B (non-canonical) DNA structures

Deletion breakpoints frequently occur within or near regions showing non-canonical (non-B) conformations, namely hairpins, cruciforms and cloverleaf-like elements.[84] Moreover, there is data supporting the involvement of helix-distorting intrinsically curved regions and long G-tetrads in eliciting instability events. In addition, higher breakpoint densities were consistently observed within GC-skewed regions and in the close vicinity of the degenerate sequence motif YMMYMNNMMHM.[85] Recently (2017) was found that all mitochodrial genomes sequenced so far contain many of inverted repeats necessary for cruciform DNA formation and these loci are particularly enriched in replication origin sites, D-loops and stem loops.[86]

Use in identification

Unlike nuclear DNA, which is inherited from both parents and in which genes are rearranged in the process of recombination, there is usually no change in mtDNA from parent to offspring. Although mtDNA also recombines, it does so with copies of itself within the same mitochondrion. Because of this and because the mutation rate of animal mtDNA is higher than that of nuclear DNA,[87] mtDNA is a powerful tool for tracking ancestry through females (matrilineage) and has been used in this role to track the ancestry of many species back hundreds of generations.

The rapid mutation rate (in animals) makes mtDNA useful for assessing genetic relationships of individuals or groups within a species and also for identifying and quantifying the phylogeny (evolutionary relationships; see phylogenetics) among different species. To do this, biologists determine and then compare the mtDNA sequences from different individuals or species. Data from the comparisons is used to construct a network of relationships among the sequences, which provides an estimate of the relationships among the individuals or species from which the mtDNAs were taken. mtDNA can be used to estimate the relationship between both closely related and distantly related species. Due to the high mutation rate of mtDNA in animals, the 3rd positions of the codons change relatively rapidly, and thus provide information about the genetic distances among closely related individuals or species. On the other hand, the substitution rate of mt-proteins is very low, thus amino acid changes accumulate slowly (with corresponding slow changes at 1st and 2nd codon positions) and thus they provide information about the genetic distances of distantly related species. Statistical models that treat substitution rates among codon positions separately, can thus be used to simultaneously estimate phylogenies that contain both closely and distantly related species[63]

Mitochondrial DNA was admitted into evidence for the first time ever in a United States courtroom in 1996 during State of Tennessee v. Paul Ware.[88]

In the 1998 United States court case of Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Patricia Lynne Rorrer,[89] mitochondrial DNA was admitted into evidence in the State of Pennsylvania for the first time.[90][91] The case was featured in episode 55 of season 5 of the true crime drama series Forensic Files (season 5).

Mitochondrial DNA was first admitted into evidence in California, United States, in the successful prosecution of David Westerfield for the 2002 kidnapping and murder of 7-year-old Danielle van Dam in San Diego: it was used for both human and dog identification.[92] This was the first trial in the U.S. to admit canine DNA.[93]

The remains of King Richard III were identified by comparing his mtDNA with that of two matrilineal descendants of his sister.[94]

History

Mitochondrial DNA was discovered in the 1960s by Margit M. K. Nass and Sylvan Nass by electron microscopy as DNase-sensitive threads inside mitochondria,[95] and by Ellen Haslbrunner, Hans Tuppy and Gottfried Schatz by biochemical assays on highly purified mitochondrial fractions.[96]

Mitochondrial sequence databases

Several specialized databases have been founded to collect mitochondrial genome sequences and other information. Although most of them focus on sequence data, some of them include phylogenetic or functional information.

- MitoSatPlant: Mitochondrial microsatellites database of viridiplantae.[97]

- MitoBreak: the mitochondrial DNA breakpoints database.[98]

- MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: a mitochondrial genome database of fish.[99] See also Cawthorn et al.[100]

- MitoZoa 2.0: a database for comparative and evolutionary analyses of mitochondrial genomes in Metazoa.[101] (no longer available)

- InterMitoBase: an annotated database and analysis platform of protein-protein interactions for human mitochondria.[102] (apparently last updated in 2010, but still available)

- Mitome: a database for comparative mitochondrial genomics in metazoan animals[103] (no longer available)

- MitoRes: a resource of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes and their products in metazoa[104] (apparently no longer being updated)

Mitochondrial mutation databases

Several specialized databases exist that report polymorphisms and mutations in the human mitochondrial DNA, together with the assessment of their pathogenicity.

See also

- Archaeogenetics of the Near East

- Clade

- CoRR hypothesis

- Haplogroup

- Heteroplasmy

- Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup

- Human mitochondrial genetics

- Mitochondrial disease

- Mitochondrial DNA (journal)

- Mitochondrial Eve

- Mitochondrial rCRS

- Paternal mtDNA transmission

- Single origin theory

- Supercluster (genetic)

- TIM/TOM complex

- Genetic history of Africa (disambiguation)

- Genetic history of Europe

- Genetic history of the British Isles

- Genetic history of the Iberian Peninsula

- Genetic history of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Genetic history of Italy

- Genetic history of North Africa

- Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia

References

- ↑ Siekevitz P (1957). "Powerhouse of the cell". Scientific American. 197 (1): 131–40. Bibcode:1957SciAm.197a.131S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0757-131.

- ↑ Iborra, Francisco J; Kimura, Hiroshi; Cook, Peter R (2004). "The functional organization of mitochondrial genomes in human cells". BMC Biology. 2: 9. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-2-9. PMC 425603. PMID 15157274.

- ↑ Sykes, B (10 September 2003). "Mitochondrial DNA and human history". The Human Genome. Wellcome Trust. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- 1 2 Anderson, S.; Bankier, A. T.; Barrell, B. G.; de Bruijn, M. H. L.; Coulson, A. R.; Drouin, J.; Eperon, I. C.; Nierlich, D. P.; Roe, B. A.; Sanger, F.; Schreier, P. H.; Smith, A. J. H.; Staden, R.; Young, I. G. (1981). "Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome". Nature. 290 (5806): 457–65. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..457A. doi:10.1038/290457a0. PMID 7219534.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial DNA: The Eve Gene". Bradshaw Foundation. Bradshaw Foundation. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ Avise, John C. (2000). Phylogeography: The history and formation of species. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674666380.

- ↑ Boursot, P.; Bonhomme, F. (1986-01-01). "Génétique et évolution du génome mitochondrial des Métazoaires". Génétique, sélection, évolution. 18: 73. doi:10.1186/1297-9686-18-1-73. ISSN 1297-9686. PMC 2713894. PMID 22879234.

- ↑ Delsuc, Frédéric; Stanhope, Michael J.; Douzery, Emmanuel J. P. (2003-08-01). "Molecular systematics of armadillos (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae): contribution of maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear genes". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 28 (2): 261–75. doi:10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00111-8. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 12878463.

- ↑ Hassanin, Alexandre; An, Junghwa; Ropiquet, Anne; Nguyen, Trung Thanh; Couloux, Arnaud (2013-03-01). "Combining multiple autosomal introns for studying shallow phylogeny and taxonomy of Laurasiatherian mammals: Application to the tribe Bovini (Cetartiodactyla, Bovidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 66 (3): 766–75. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.11.003. ISSN 1095-9513. PMID 23159894.

- ↑ Wiesner, Rudolf J.; Rüegg, J.Caspar; Morano, Ingo (1992). "Counting target molecules by exponential polymerase chain reaction: Copy number of mitochondrial DNA in rat tissues". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 183 (2): 553–9. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(92)90517-O. PMID 1550563.

- 1 2 3 Johnston, Iain G.; Williams, Ben P. (2016). "Evolutionary Inference across Eukaryotes Identifies Specific Pressures Favoring Mitochondrial Gene Retention". Cell Systems. 2 (2): 101–11. doi:10.1016/j.cels.2016.01.013. PMID 27135164.

- ↑ van der Giezen, Mark; Tovar, Jorge; Clark, C. Graham (2005). "Mitochondrion‐Derived Organelles in Protists and Fungi". A Survey of Cell Biology. International Review of Cytology. 244. pp. 175–225. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(05)44005-X. ISBN 978-0-12-364648-4. PMID 16157181.

- ↑ Adams, Keith L; Palmer, Jeffrey D (2003). "Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: gene loss and transfer to the nucleus". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 29 (3): 380–95. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00194-5. PMID 14615181.

- ↑ Björkholm, Patrik; Harish, Ajith; Hagström, Erik; Ernst, Andreas M.; Andersson, Siv G. E. (2015). "Mitochondrial genomes are retained by selective constraints on protein targeting". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (33): 10154–61. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11210154B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421372112. PMC 4547212. PMID 26195779.

- ↑ Allen, John F. (2015). "Why chloroplasts and mitochondria retain their own genomes and genetic systems: Colocation for redox regulation of gene expression". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (33): 10231–8. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11210231A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1500012112. PMC 4547249. PMID 26286985.

- ↑ Wolff, J N; Gemmell, N J (2008). "Lost in the zygote: the dilution of paternal mtDNA upon fertilization". Heredity. 101 (5): 429–34. doi:10.1038/hdy.2008.74. PMID 18685570.

- ↑ Gabriel, Maria San; Chan, Sam W.; Alhathal, Naif; Chen, Junjian Z.; Zini, Armand (2012). "Influence of microsurgical varicocelectomy on human sperm mitochondrial DNA copy number: A pilot study". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 29 (8): 759–64. doi:10.1007/s10815-012-9785-z. PMC 3430774. PMID 22562241.

- ↑ Schatten, Gerald; Sutovsky, Peter; Moreno, Ricardo D.; Ramalho-Santos, João; Dominko, Tanja; Simerly, Calvin (1999). "Development: Ubiquitin tag for sperm mitochondria". Nature. 402 (6760): 371–72. Bibcode:1999Natur.402..371S. doi:10.1038/46466. PMID 10586873. Discussed in: Travis, John (2000). "Mom's Eggs Execute Dad's Mitochondria". Science News. 157: 5. doi:10.2307/4012086. JSTOR 4012086. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007.

- ↑ "Hiring a DNA Testing Company Genealogy". Family Search. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-02.

- ↑ Vila, C.; Savolainen, P; Maldonado, J. E.; Amorim, I. R.; Rice, J. E.; Honeycutt, R. L.; Crandall, K. A.; Lundeberg, J; Wayne, R. K. (1997). "Multiple and Ancient Origins of the Domestic Dog". Science. 276 (5319): 1687–89. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID 9180076.

- ↑ Gilbert, M. Thomas P.; Wolff, Jonci N.; White, Daniel J.; Woodhams, Michael; White, Helen E.; Gemmell, Neil J. (2011). "The Strength and Timing of the Mitochondrial Bottleneck in Salmon Suggests a Conserved Mechanism in Vertebrates". PLoS ONE. 6 (5): e20522. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620522W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020522. PMC 3105079. PMID 21655224.

- ↑ Cree, Lynsey M; Samuels, David C; de Sousa Lopes, Susana Chuva; Rajasimha, Harsha Karur; Wonnapinij, Passorn; Mann, Jeffrey R; Dahl, Hans-Henrik M; Chinnery, Patrick F (2008). "A reduction of mitochondrial DNA molecules during embryogenesis explains the rapid segregation of genotypes". Nature Genetics. 40 (2): 249–54. doi:10.1038/ng.2007.63. PMID 18223651.

- ↑ Cao, Liqin; Shitara, Hiroshi; Horii, Takuro; Nagao, Yasumitsu; Imai, Hiroshi; Abe, Kuniya; Hara, Takahiko; Hayashi, Jun-Ichi; Yonekawa, Hiromichi (2007). "The mitochondrial bottleneck occurs without reduction of mtDNA content in female mouse germ cells". Nature Genetics. 39 (3): 386–90. doi:10.1038/ng1970. PMID 17293866.

- ↑ Wai, Timothy; Teoli, Daniella; Shoubridge, Eric A (2008). "The mitochondrial DNA genetic bottleneck results from replication of a subpopulation of genomes". Nature Genetics. 40 (12): 1484–88. doi:10.1038/ng.258. PMID 19029901.

- 1 2 3 Johnston, Iain G; Burgstaller, Joerg P; Havlicek, Vitezslav; Kolbe, Thomas; Rülicke, Thomas; Brem, Gottfried; Poulton, Jo; Jones, Nick S (2015). "Stochastic modelling, Bayesian inference, and new in vivo measurements elucidate the debated mtDNA bottleneck mechanism". eLife. 4: e07464. doi:10.7554/eLife.07464. PMC 4486817. PMID 26035426.

- ↑ Passamonti, Marco; Ghiselli, Fabrizio (2009). "Doubly Uniparental Inheritance: Two Mitochondrial Genomes, One Precious Model for Organelle DNA Inheritance and Evolution". DNA and Cell Biology. 28 (2): 79–89. doi:10.1089/dna.2008.0807. PMID 19196051.

- ↑ Kondo, Rumi; Matsuura, Etsuko T.; Chigusa, Sadao I. (1992). "Further observation of paternal transmission of Drosophila mitochondrial DNA by PCR selective amplification method". Genetical Research. 59 (2): 81–84. doi:10.1017/S0016672300030287. PMID 1628820.

- ↑ Wolff, J N; Nafisinia, M; Sutovsky, P; Ballard, J W O (2013). "Paternal transmission of mitochondrial DNA as an integral part of mitochondrial inheritance in metapopulations of Drosophila simulans". Heredity. 110 (1): 57–62. doi:10.1038/hdy.2012.60. PMC 3522233. PMID 23010820.

- ↑ Meusel, Michael S.; Moritz, Robin F. A. (1993). "Transfer of paternal mitochondrial DNA during fertilization of honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) eggs". Current Genetics. 24 (6): 539–43. doi:10.1007/BF00351719. PMID 8299176.

- ↑ Fontaine, Kathryn M.; Cooley, John R.; Simon, Chris (2007). "Evidence for Paternal Leakage in Hybrid Periodical Cicadas (Hemiptera: Magicicada spp.)". PLoS ONE. 2 (9): e892. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..892F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000892. PMC 1963320. PMID 17849021.

- ↑ Alexander, Michelle; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Molak, Martyna; Barnett, Ross; Carlborg, Örjan; Dorshorst, Ben; Honaker, Christa; Besnier, Francois; Wahlberg, Per; Dobney, Keith; Siegel, Paul; Andersson, Leif; Larson, Greger (2015). "Mitogenomic analysis of a 50-generation chicken pedigree reveals a rapid rate of mitochondrial evolution and evidence for paternal mtDNA inheritance". Biology Letters. 11 (10): 20150561. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0561. PMC 4650172. PMID 26510672.

- ↑ Gyllensten, Ulf; Wharton, Dan; Josefsson, Agneta; Wilson, Allan C. (1991). "Paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in mice". Nature. 352 (6332): 255–57. Bibcode:1991Natur.352..255G. doi:10.1038/352255a0. PMID 1857422.

- ↑ Shitara, Hiroshi; Hayashi, Jun-Ichi; Takahama, Sumiyo; Kaneda, Hideki; Yonekawa, Hiromichi (1998). "Maternal Inheritance of Mouse mtDNA in Interspecific Hybrids: Segregation of the Leaked Paternal mtDNA Followed by the Prevention of Subsequent Paternal Leakage". Genetics. 148 (2): 851–57. PMC 1459812. PMID 9504930.

- ↑ Zhao, X; Li, N; Guo, W; Hu, X; Liu, Z; Gong, G; Wang, A; Feng, J; Wu, C (2004). "Further evidence for paternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in the sheep (Ovis aries)". Heredity. 93 (4): 399–403. doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800516. PMID 15266295.

- ↑ Steinborn, Ralf; Zakhartchenko, Valeri; Jelyazkov, Jivko; Klein, Dieter; Wolf, Eckhard; Müller, Mathias; Brem, Gottfried (1998). "Composition of parental mitochondrial DNA in cloned bovine embryos". FEBS Letters. 426 (3): 352–56. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00350-0. PMID 9600265.

- ↑ Schwartz, Marianne; Vissing, John (2002). "Paternal Inheritance of Mitochondrial DNA". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (8): 576–80. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa020350. PMID 12192017.

- ↑ Frith, Maxine (14 October 2003). "Ban on scientists trying to create three-parent baby". The Independent.

- ↑ Roberts, Michelle (2016-09-27). "First 'three person baby' born using new method". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- ↑ Nosek, Jozef; Tomáška, L'Ubomı́r; Fukuhara, Hiroshi; Suyama, Yoshitaka; Kováč, Ladislav (1998). "Linear mitochondrial genomes: 30 years down the line". Trends in Genetics. 14 (5): 184–88. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(98)01443-7. PMID 9613202.

- ↑ Balaresque, Patricia; Bowden, Georgina R.; Adams, Susan M.; Leung, Ho-Yee; King, Turi E.; Rosser, Zoë H.; Goodwin, Jane; Moisan, Jean-Paul; Richard, Christelle; Millward, Ann; Demaine, Andrew G.; Barbujani, Guido; Previderè, Carlo; Wilson, Ian J.; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Jobling, Mark A. (2010). "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for European Paternal Lineages". PLoS Biology. 8 (1): e1000285. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000285. PMC 2799514. PMID 20087410.

- ↑ Barroso Lima, Nicholas Costa; Prosdocimi, Francisco (2017-01-27). "The heavy strand dilemma of vertebrate mitochondria on genome sequencing age: number of encoded genes or G + T content?". Mitochondrial DNA Part A. 29 (2): 300–302. doi:10.1080/24701394.2016.1275603. ISSN 2470-1394.

- 1 2 Homo sapiens mitochondrion, complete genome. "Revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS): accession NC_012920", National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved on 20 February 2017.

- ↑ Sloan, D.B.; Alverson, A.J.; Chuckalovcak, J.P.; Wu, M.; McCauley, D.E.; Palmer, J.D.; Taylor, D.R. (2012). "Rapid evolution of enormous, multichromosomal genomes in flowering plant mitochondria with exceptionally high mutation rates". PLoS Biol. 10 (1): e1001241. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001241.

- ↑ Ward, Bernard L.; Anderson, Robert S.; Bendich, Arnold J. (1981). "The mitochondrial genome is large and variable in a family of plants (Cucurbitaceae)". Cell. 25 (3): 793–803. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(81)90187-2. PMID 6269758.

- ↑ Alverson, Andrew J; Rice, Danny W; Dickinson, Stephanie; Barry, Kerrie; Palmer, Jeffrey D (2011). "Origins and Recombination of the Bacterial-Sized Multichromosomal Mitochondrial Genome of Cucumber". The Plant Cell. 23 (7): 2499–513. doi:10.1105/tpc.111.087189. JSTOR 41433488. PMC 3226218. PMID 21742987.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)" (PDF). Integrated DNA Technologies.

- ↑ Tyagi, Suchi; Pande, Veena; Das, Aparup (2014-02-19). "Whole Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of an Indian Plasmodium falciparum Field Isolate". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 52 (1): 99–103. doi:10.3347/kjp.2014.52.1.99. ISSN 0023-4001.

- 1 2 3 Kolesnikov, A. A.; Gerasimov, E. S. (2012). "Diversity of Mitochondrial Genome Organization". Biochemistry Moscow. 77 (13): 1424–35. doi:10.1134/S0006297912130020. PMID 23379519.

- ↑ Yakubovskaya, E.; Chen, Z.; Carrodeguas, J. A.; Kisker, C.; Bogenhagen, D. F. (2005). "Functional Human Mitochondrial DNA Polymerase Forms a Heterotrimer". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (1): 374–82. doi:10.1074/jbc.M509730200. PMID 16263719.

- ↑ Jemt, E.; Farge, G.; Backstrom, S.; Holmlund, T.; Gustafsson, C. M.; Falkenberg, M. (2011). "The mitochondrial DNA helicase TWINKLE can assemble on a closed circular template and support initiation of DNA synthesis". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (21): 9238–49. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr653. PMC 3241658. PMID 21840902.

- 1 2 3 St. John, J. C.; Facucho-Oliveira, J.; Jiang, Y.; Kelly, R.; Salah, R. (2010). "Mitochondrial DNA transmission, replication and inheritance: A journey from the gamete through the embryo and into offspring and embryonic stem cells". Human Reproduction Update. 16 (5): 488–509. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq002. PMID 20231166.

- ↑ Falkenberg, Maria; Larsson, Nils-Göran; Gustafsson, Claes M. (2007-06-19). "DNA Replication and Transcription in Mammalian Mitochondria". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 76 (1): 679–99. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.152028.

- ↑ Ojala, Deanna; Montoya, Julio; Attardi, Giuseppe (1981-04-09). "tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria". Nature. 290 (5806): 470–74. Bibcode:1981Natur.290..470O. doi:10.1038/290470a0. PMID 7219536.

- 1 2 Alexeyev, Mikhail F. (2009). "Is there more to aging than mitochondrial DNA and reactive oxygen species?". FEBS Journal. 276 (20): 5768–87. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07269.x. PMC 3097520. PMID 19796285.

- ↑ Anson, R. Michael; Hudson, Edgar; Bohr, Vilhelm A. (2000). "Mitochondrial endogenous oxidative damage has been overestimated". FASEB Journal. 14 (2): 355–60. PMID 10657991.

- ↑ Thorslund, Tina; Sunesen, Morten; Bohr, Vilhelm A.; Stevnsner, Tinna (2002). "Repair of 8-oxoG is slower in endogenous nuclear genes than in mitochondrial DNA and is without strand bias". DNA Repair. 1 (4): 261–73. doi:10.1016/S1568-7864(02)00003-4. PMID 12509245.

- ↑ Guliaeva, NA; Kuznetsova, EA; Gaziev, AI (2006). "Белки, ассоциированные с митохондриальной ДНК, защищают ее от воздействия рентгеновского излучения и перекиси водорода" [Proteins associated with mitochondrial DNA protect it against the action of X-rays and hydrogen peroxide]. Biofizika (in Russian). 51 (4): 692–97. PMID 16909848.

- ↑ Alexeyev, M.; Shokolenko, I.; Wilson, G.; Ledoux, S. (2013). "The Maintenance of Mitochondrial DNA Integrity – Critical Analysis and Update". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 5 (5): a012641. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a012641. PMC 3632056. PMID 23637283.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2010). "Mutation". In Monosson, E.; Cleveland, C. J. Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington DC: National Council for Science and the Environment.

- ↑ Ledoux, Susan P.; Alexeyev, Mikhail F.; Wilson, Glenn L. (2004). "Mitochondrial DNA and aging". Clinical Science. 107 (4): 355–64. doi:10.1042/CS20040148. PMID 15279618.

- ↑ Burgstaller, J. P.; Johnston, I. G.; Poulton, J. (2015). "Mitochondrial DNA disease and developmental implications for reproductive strategies". Molecular Human Reproduction. 21 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1093/molehr/gau090. PMC 4275042. PMID 25425607.

- ↑ Burgstaller, Joerg Patrick; Johnston, Iain G.; Jones, Nick S.; Albrechtová, Jana; Kolbe, Thomas; Vogl, Claus; Futschik, Andreas; Mayrhofer, Corina; Klein, Dieter; Sabitzer, Sonja; Blattner, Mirjam; Gülly, Christian; Poulton, Joanna; Rülicke, Thomas; Piálek, Jaroslav; Steinborn, Ralf; Brem, Gottfried (2014). "mtDNA Segregation in Heteroplasmic Tissues Is Common In Vivo and Modulated by Haplotype Differences and Developmental Stage". Cell Reports. 7 (6): 2031–41. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.020. PMC 4570183. PMID 24910436.

- 1 2 Taylor, Robert W.; Turnbull, Doug M. (2005). "Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease". Nature Reviews Genetics. 6 (5): 389–402. doi:10.1038/nrg1606. PMC 1762815. PMID 15861210.

- ↑ Angelini, C; Bello, L; Spinazzi, M; Ferrati, C (1 November 2016). "Mitochondrial disorders of the nuclear genome". Acta Myologica. 28 (1): 16–23. ISSN 1128-2460. PMC 2859630. PMID 19772191.

- ↑ Reguly, Brian; Jakupciak, John P.; Parr, Ryan L. (2010). "3.4 kb mitochondrial genome deletion serves as a surrogate predictive biomarker for prostate cancer in histopathologically benign biopsy cores". Canadian Urological Association Journal. 4 (5): E118–22. PMC 2950771. PMID 20944788.

- ↑ Robinson, K; Creed, J; Reguly, B; Powell, C; Wittock, R; Klein, D; Maggrah, A; Klotz, L; Parr, R L; Dakubo, G D (2010). "Accurate prediction of repeat prostate biopsy outcomes by a mitochondrial DNA deletion assay". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 13 (2): 126–31. doi:10.1038/pcan.2009.64. PMID 20084081.

- ↑ de Grey, Aubrey. The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging (PDF). ISBN 1-57059-564-X.

- ↑ Lewis, Kaitlyn N.; Andziak, Blazej; Yang, Ting; Buffenstein, Rochelle (2013). "The Naked Mole-Rat Response to Oxidative Stress: Just Deal with It". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 19 (12): 1388–99. doi:10.1089/ars.2012.4911. PMC 3791056. PMID 23025341.

- ↑ Shigenaga, M. K.; Hagen, T. M.; Ames, B. N. (1994). "Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 91 (23): 10771–78. Bibcode:1994PNAS...9110771S. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. JSTOR 2365473. PMC 45108. PMID 7971961.

- ↑ Trifunovic, A.; Hansson, A.; Wredenberg, A.; Rovio, A. T.; Dufour, E.; Khvorostov, I.; Spelbrink, J. N.; Wibom, R.; Jacobs, H. T.; Larsson, N.-G. (2005). "Somatic mtDNA mutations cause aging phenotypes without affecting reactive oxygen species production". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (50): 17993–98. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10217993T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508886102. JSTOR 4152716. PMC 1312403. PMID 16332961.

- ↑ Aledo, Juan Carlos; Li, Yang; De Magalhães, João Pedro; Ruíz-Camacho, Manuel; Pérez-Claros, Juan Antonio (2011). "Mitochondrially encoded methionine is inversely related to longevity in mammals". Aging Cell. 10 (2): 198–207. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00657.x. PMID 21108730.

- ↑ Ferrari, Carlos K. B. (2004). "Functional foods, herbs and nutraceuticals: Towards biochemical mechanisms of healthy aging". Biogerontology. 5 (5): 275–89. doi:10.1007/s10522-004-2566-z. PMID 15547316.

- ↑ Taylor, Robert W (2005). "Gene therapy for the treatment of mitochondrial DNA disorders". Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 5 (2): 183–94. doi:10.1517/14712598.5.2.183. PMID 15757380.

- ↑ Bjelakovic, Goran; Nikolova, Dimitrinka; Gluud, Christian (2013). "Antioxidant Supplements to Prevent Mortality". JAMA. 310 (11): 1178–79. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.277028. PMID 24045742.

- ↑ Wang J, Xiong S, Xie C, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA (May 2005). "Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in Alzheimer's disease". J. Neurochem. 93 (4): 953–62. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03053.x. PMID 15857398.

- ↑ Bonda DJ, Wang X, Lee HG, Smith MA, Perry G, Zhu X (April 2014). "Neuronal failure in Alzheimer's disease: a view through the oxidative stress looking-glass". Neurosci Bull. 30 (2): 243–52. doi:10.1007/s12264-013-1424-x. PMC 4097013. PMID 24733654.

- ↑ Liu Z, Zhou T, Ziegler AC, Dimitrion P, Zuo L (2017). "Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications". Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017: 2525967. doi:10.1155/2017/2525967. PMC 5529664. PMID 28785371.

- ↑ Ayala-Peña S (September 2013). "Role of oxidative DNA damage in mitochondrial dysfunction and Huntington's disease pathogenesis". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 62: 102–10. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.017. PMC 3722255. PMID 23602907.

- ↑ Kikuchi H, Furuta A, Nishioka K, Suzuki SO, Nakabeppu Y, Iwaki T (April 2002). "Impairment of mitochondrial DNA repair enzymes against accumulation of 8-oxo-guanine in the spinal motor neurons of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Acta Neuropathol. 103 (4): 408–14. doi:10.1007/s00401-001-0480-x. PMID 11904761.

- ↑ Lehmann, Gilad; Budovsky, Arie; Muradian, K. Muradian; Fraifeld, Vadim E. (2006). "Mitochondrial genome anatomy and species-specific lifespan". Rejuvenation Res. 9 (2): 223–26. doi:10.1089/rej.2006.9.223. PMID 16706648.

- 1 2 Lehmann, Gilad; Segal, Elena; Muradian, K. Muradian; Fraifeld, Vadim E. (2008). "Do mitochondrial DNA and metabolic rate complement each other in determination of the mammalian maximum longevity?". Rejuvenation Res. 11 (2): 409–17. doi:10.1089/rej.2008.0676. PMID 18442324.

- ↑ Lehmann, Gilad; Muradian, K. Muradian; Fraifeld, Vadim E. (2013). "Telomere length and body temperature-independent determinants of mammalian longevity?". Front Genet. 4 (111). doi:10.3389/fgene.2013.00111. PMC 3680702. PMID 23781235.

- ↑ Toren, Dmitri; Barzilay, Thomer; Tacutu, Robi; Lehmann, Gilad; Muradian, Khachik K.; Fraifeld, Vadim E. (2016). "MitoAge: a database for comparative analysis of mitochondrial DNA, with a special focus on animal longevity". Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1): D1262–5. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv1187. PMC 4702847. PMID 26590258.

- ↑ Damas, J; Carneiro, J; Goncalves, J; Stewart, JB; Samwels, DC; Amorim, A; Pereira, F (2012). "Mitochondrial DNA deletions are associated with non-B DNA conformations". Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (16): 7606–621. doi:10.1093/nar/gks500. PMC 3439893. PMID 22661583.

- ↑ Bielas, Jason H.; Oliveira, Pedro H.; Lobato da Silva, Cláudia; Cabral, Joaquim M. S. (2013). "An Appraisal of Human Mitochondrial DNA Instability: New Insights into the Role of Non-Canonical DNA Structures and Sequence Motifs". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e59907. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...859907O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059907. PMC 3612095. PMID 23555828.

- ↑ Cechova, Jana.; Lysek, Jiri.; Bartas, Martin; Brazda, Vaclav (2017). "Complex analyses of inverted repeats in mitochondrial genomes revealed their importance and variability". Bioinformatics. 34. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btx729.

- ↑ Brown, W. M.; George, M.; Wilson, A. C. (1979). "Rapid evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 76 (4): 1967–71. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.1967B. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.4.1967. JSTOR 69636. PMC 383514. PMID 109836.

- ↑ Davis, C. Leland (1998). "Mitochondrial DNA: State of Tennessee v. Paul Ware" (PDF). Profiles in DNA. 1 (3): 6–7.

- ↑ Court case name listed in the appeal. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Defense lawyer. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ↑ Garlicki, Debbie (11 March 1998). "DNA Tests Got Rorrer Life In Jail". The Morning Call.

- ↑ "Judge allows DNA in Samantha Runnion case," Associated Press, 18 February 2005. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ↑ "Canine DNA Admitted In California Murder Case," Pit Bulletin Legal News, 5 December 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (4 February 2013). "Richard III: DNA confirms twisted bones belong to king". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ↑ Nass, M. M. K.; Nass, S (1963). "Intramirochondrial Fibers With DNA Characteristics: I. Fixation and Electron Staining Reactions". The Journal of Cell Biology. 19 (3): 593–611. doi:10.1083/jcb.19.3.593. PMC 2106331. PMID 14086138.

- ↑ Schatz, G.; Haslbrunner, E.; Tuppy, H. (1964). "Deoxyribonucleic acid associated with yeast mitochondria". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 15 (2): 127–32. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(64)90311-0. PMID 26410904.

- ↑ Kumar, Manjeet; Kapil, Aditi; Shanker, Asheesh (2014). "Mito Sat Plant: Mitochondrial microsatellites database of viridiplantae". Mitochondrion. 19: 334–37. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2014.02.002. PMID 24561221.

- ↑ Damas, J.; Carneiro, J.; Amorim, A.; Pereira, F. (2013). "Mito Break: The mitochondrial DNA breakpoints database". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (Database issue): D1261–68. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt982. PMC 3965124. PMID 24170808.

- ↑ Iwasaki, W.; Fukunaga, T.; Isagozawa, R.; Yamada, K.; Maeda, Y.; Satoh, T. P.; Sado, T.; Mabuchi, K.; Takeshima, H.; Miya, M.; Nishida, M. (2013). "Mito Fish and Mito Annotator: A Mitochondrial Genome Database of Fish with an Accurate and Automatic Annotation Pipeline". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (11): 2531–40. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst141. PMC 3808866. PMID 23955518.

- ↑ Cawthorn, Donna-Mareè; Steinman, Harris Andrew; Corli Witthuhn, R. (2011). "Establishment of a mitochondrial DNA sequence database for the identification of fish species commercially available in South Africa". Molecular Ecology Resources. 11 (6): 979–91. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03039.x. PMID 21689383.

- ↑ d'Onorio De Meo, P.; d'Antonio, M.; Griggio, F.; Lupi, R.; Borsani, M.; Pavesi, G.; Castrignano, T.; Pesole, G.; Gissi, C. (2011). "Mito Zoa 2.0: A database resource and search tools for comparative and evolutionary analyses of mitochondrial genomes in Metazoa". Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (Database issue): D1168–72. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1144. PMC 3245153. PMID 22123747.

- ↑ Gu, Zuguang; Li, Jie; Gao, Song; Gong, Ming; Wang, Junling; Xu, Hua; Zhang, Chenyu; Wang, Jin (2011). "Inter Mito Base: An annotated database and analysis platform of protein-protein interactions for human mitochondria". BMC Genomics. 12: 335. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-335. PMC 3142533. PMID 21718467.

- ↑ Lee, Y. S.; Oh, J.; Kim, Y. U.; Kim, N.; Yang, S.; Hwang, U. W. (2007). "Mitome: Dynamic and interactive database for comparative mitochondrial genomics in metazoan animals". Nucleic Acids Research. 36 (Database issue): D938–42. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm763. PMC 2238945. PMID 17940090.

- ↑ Catalano, Domenico; Licciulli, Flavio; Turi, Antonio; Grillo, Giorgio; Saccone, Cecilia; d'Elia, Domenica (2006). "Mito Res: A resource of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes and their products in Metazoa". BMC Bioinformatics. 7: 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-7-36. PMC 1395343. PMID 16433928.

External links