Rollins Pass

| Rollins Pass | |

|---|---|

Riflesight Notch trestle on Rollins Pass | |

| Elevation | 11,676.79 ft (3,559 m)[1] |

| Traversed by |

|

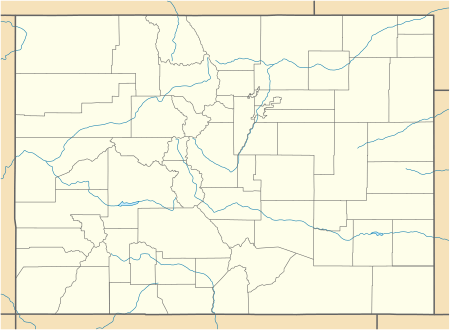

| Location | Boulder, Gilpin, and Grand counties, Colorado, U.S. |

| Range | Front Range |

| Coordinates | 39°56′03″N 105°40′58″W / 39.93417°N 105.68278°WCoordinates: 39°56′03″N 105°40′58″W / 39.93417°N 105.68278°W[1] |

| Topo map | USGS East Portal |

Colorado | |

|

Rollinsville and Middle Park Wagon Road / Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway Hill Route Historic District | |

| Area | 436.3 acres (176.6 ha) |

| Built | 1873 |

| Built by | Rollins, John Q.A. |

| NRHP reference # | 80000881, 97001114[8] |

| Added to NRHP | Tuesday, September 30, 1980 |

Rollins Pass, elevation 11,676.79 ft (3,559.09 m), is a mountain pass and active archaeological site[9] in the Southern Rocky Mountains of north-central Colorado in the United States. The pass is located on and traverses the Continental Divide of the Americas at the crest of the Front Range southwest of Boulder and is located approximately five miles east and opposite the resort in Winter Park—in the general area between Winter Park and Rollinsville. Rollins Pass is at the boundaries of Boulder, Gilpin, and Grand counties. Over the past 10,000 years,[9] the pass provided a route over the Continental Divide between the Atlantic Ocean watershed of South Boulder Creek (in the basin of the South Platte River) with the Pacific Ocean watershed of the Fraser River, a tributary of the Colorado River.

Rollins Pass was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1980[8] and is listed as one of the most endangered sites in Colorado.[2]:117

Naming

Rollins Pass is the sole, official name recognized by both the United States Geological Survey and the United States Board on Geographic Names (BGN); a decision card was issued on Wednesday, December 7, 1904.[10] The pass was first known as Boulder Pass[2]:8—one of two variant names accepted by the BGN—the other being Rogers Pass.[11]

In Grand County, Rollins Pass is given the sobriquet of Corona Pass, named for the apex station at the summit, Corona.[2]:8 However, it is inconsistent, as well as atypical, to refer to mountain passes by the names of their apex stations. Fremont Pass, for example, is not named Climax Pass; nor is La Veta Pass referred to as Fir Pass.[12]

Elevation

The elevation of '11,660 feet' commonly attributed to Rollins Pass (note the McClure sketch later in this article) "reflects what might have been an original survey value obtained during either the late wagon road era or early railroad construction…. The actual benchmarked survey elevation value of the summit of Rollins Pass is 11,671 feet (NGVD29), obtained during a 1952 second-order level line run from State Bridge to Denver by the US Coast and Geodetic Survey (predecessor to the National Geodetic Survey). When adjusted to NAVD88, the elevation is, without doubt, 11,676.79 feet."[2]:64

Description

Rollins Pass has been in continuous use for millennia: first as an internationally significant game drive complex that was hand-constructed and used by Paleo-Indians more than 10,000 years ago through the mid-19th century;[9] followed by nearly two decades as a wagon road from 1862–1880; as a rail route (under survey, construction, and later operational) from 1880 to 1928; as a primitive automobile road from 1936 to 1956; and for the past 62 years—from 1956 through present day—as a motor vehicle road.

The pass is traversed by Paleo-Indian (Native American) game drive complexes,[2]:8 hiking trails, including the Continental Divide Trail; an airway radial (V8),[3] a 10" Xcel Energy high-pressure natural gas pipeline,[4][5][6][7] and two roads:

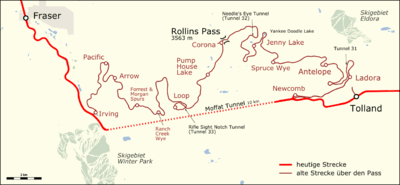

- The first dirt road is the Rollinsville and Middle Park Wagon Road, created in the early 1860s and this route predates the rail line. This road employed much of what would later become Rollins Pass. This original wagon route, now called the Boulder Wagon Road, took a steep counterclockwise route up Guinn Mountain encircling Yankee Doodle Lake before continuing to head west/northwest to proceed over the summit and down into the Middle Park valley near present-day Winter Park and Fraser, Colorado.

- The second dirt road is mostly the former roadbed of the Denver, Northwestern, and Pacific Railway, that later became the Denver and Salt Lake Railway. This high-altitude railroad grade was part of the Moffat Road and this route was replaced (and later abandoned) by the opening of the Moffat Tunnel in 1928; the rails and ties were removed from Rollins Pass in 1936; however, some rail segments as well as ties, made of pine, oak, and walnut, can still be seen, along with planking used for snowsheds.[13][14][2]:124

Geology

The Front Range was created by the Laramide Orogeny, the last of three major mountain-building events, which occurred between 70 and 40 million years ago. Tectonic activity during the Cenozoic Era changed the Ancestral Rocky Mountains via block uplift, eventually forming the Rocky Mountains as they exist today. The geologic make-up of Rollins Pass and the surrounding areas were also affected by deformation and erosion during the Cenozoic Era. Many sedimentary rocks from the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras exist in the basins surrounding the pass.

History

Rollins Pass as a prehistoric Paleo-Indian hunting complex

Paleo-Indians (early Native Americans) were the first to utilize Rollins Pass as a natural, low crossing over the Continental Divide for the purposes of communal hunting of large game, including bighorn sheep and elk.[15] There are more than 96 documented game drives, including the Olson game drive, found largely above timberline and near the summits of multiple mountain ridges. Handmade rock walls drove prey toward hunters waiting in blinds. These unique high-altitude constructs were built, refined, and continually used over millennia.[16][17] Currently the game drives are being studied by Colorado State University archaeology graduate and PhD students led by Dr. Jason M. LaBelle, the associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at the Center for Mountain and Plains Archaeology in Fort Collins, Colorado. The game drives built on—and over—Rollins Pass have international significance.[9]

The Olson game drive

The Olson site (5BL147) is a multi-component rock walled game drive and is but one part of a much larger game drive complex located on Rollins Pass. Byron Olson and James Benedict conducted work at the site in the late-1960s. Present-day archaeology teams built on Olson and Benedict's work to expand the overview of the site using modern techniques. As of 2013, at least 45 blinds as well as 1,307 meters of rock walls are present across the Olson site; the purposes of which were to funnel game upslope to waiting hunters. Both radiocarbon and lichenometric dating suggest occupation by Native Americans spanning the last 3,200 years, with diagnostic tools suggesting even older use of the site, dating back to more than 10,000 years ago.[9]

Other significant game drives

Game drives at other locations on Rollins Pass yield hundreds of additional blinds and miles of rock walls.[18]

Rollins Pass as a late-prehistoric and historic Native American route

Rollins Pass has a documented history as a migratory route, hunting trail, and battlefield among the late prehistoric and contact-period Indians of Colorado.[19]

The Indians, both Ute and Arapahoe, used Rollins Pass. While it is possible to ride a horse across the Range at almost any point except some of the higher and rougher peaks, the Indians were as much interested as the white man in seeking a good grade. Instead of wagons they used teepee poles as drag-poles for transportation of supplies and papooses, and it was necessary that they follow easy grades and broad level country, wherever practical.

— Edgar McMechen, Romantic History of Rollins Pass, Municipal Facts, Volume VI, numbers 8 & 9

Rollins Pass as an historic wagon road

The first recorded use of the pass by a wagon train was in 1862, nearly 14 years before Colorado became a state.[20] Rollins Pass is named for John Quincy Adams Rollins, a Colorado pioneer from a family of pioneers,[2]:18 who constructed a toll wagon road over the pass in the 1873,[21] providing a route between the Colorado Front Range and Middle Park.[22][23]

John Quincy Adams Rollins

John Q.A. Rollins was born on Sunday, June 16, 1816 in Gilmanton, New Hampshire and was the son of a New England minister.[24][25] Rollins is described as being a strong man and an extensive character, popular with almost everybody whom he did not owe and his one predominating fault was his failure to pay his debts. Newspapers cited that he was so careless about his credit that he could not keep track of all his creditors, and in turn, they had trouble keeping track of him.[26] Rollins died on Wednesday, June 20, 1894 and is buried in Colorado's oldest operating cemetery, Riverside, in block 5, lot 12. His simple tombstone reads, "John Q.A. Rollins | Colorado Pioneer of Rollinsville and Rollins Pass."[2]:18 Colonel Rollins' newspaper obituary mentions, "No man in Northern Colorado was better known nor counted more warm friends than John Q.A. Rollins."[27]

Middle Park and South Boulder Wagon Road Company

Rollins received approval for his toll wagon road on Tuesday, February 6, 1866. The Council and House of Representatives of Colorado Territory passed an act signed by the governor approving the wagon road as the "Middle Park and South Boulder Wagon Road Company." Records reflect the incorporators as "John Q.A. Rollins, Perley Dodge, Frederic C. Weir."[2]:21[24] Yet, the "Rollins road" through Boulder Pass was not completed until the first half of August 1873.[28][29][30][31][32] While the newspaper articles cited "wagons can now be taken over this route without the slightest trouble,"[28] other articles countered, "the trail... is splendid for horses but fearful for wagons"[33] and "the rocks, mud-holes, bogs, creeks, boulders and sidling ledges of that road, can only be appreciated by being seen, the only wonder is that a wagon can be taken over at all."[34] Other articles were a bit more grim, referring to the wagon road as a "little more than the rocky ridge of a precipice along which lurked death and disaster."[35] Newspaper records reflect on Friday, June 12, 1874, James Harvey Crawford along with his wife, Margaret Emerine Bourn Crawford,[36] made pioneer history as the first (nonindigenous) couple to cross Rollins Pass by wagons, and Mrs. Crawford is credited as the first woman to cross the pass. That day held many challenges, including a two-hour blizzard, "which was of terrific violence" and she remarked in a newspaper article, "the bumping was so hard I thought I was nearly dead."[37] As there was no formal road constructed from "Yankee Doodle Camp on up, only an Indian trail, she and the children had been left behind while her husband took the wagon pulled by a pair of mules, a team of horses and a yoke of oxen on up and camped. Then he came back for her with the team and the running gear only of the wagon, and she had to hold the children on someway, despite the dreadful bumping"[38][39] with the "wagon almost standing on end."[40]

The pass was used heavily in the latter half of the 19th century by settlers and at one time as many as 12,000 cattle at a time were driven over the pass.[41][42] The wagon road had one tollgate and the following rate structure: “For each vehicle drawn by two animals, two dollars and fifty cents; for each additional two animals, twenty-five cents; each vehicle drawn by one animal, one dollar and fifty cents; horse and rider and pack animals, twenty-five cents; loose stock, five cents per head . . . horse with rider, or pack animal with pack, ten cents.” The cost for nonpayment of a toll was the same as causing intentional damage to the road: $25.[2]:22

According to the manuscript of Martin Parsons, "Twistin Dogies Tails Over Rollins Pass", each summer, Mr. Rollins would “build a cribbing of logs… and would fill the center with rocks and earth, which helped reduce the grade between the hills.” The original log cribbing can be seen today on the narrow ridge of Guinn Mountain, north of Yankee Doodle Lake.

The road began to fall out of use and into disrepair in 1880, approximately one year before early railroading attempts over the pass begun.[21][43][44]

Mining efforts on Guinn Mountain at Yankee Doodle Lake

Guinn Mountain, encircling Yankee Doodle Lake, was used for mining from the early 1870s through the establishment of the railroad in 1904.

This area held “five patented lode claims, one patented placer claim, several prospect pits and the dump of one caved adit.” This caved adit, once 365-feet-long,[45] then lengthened to 850-feet,[46] is still shown as a mine on United States Geological Survey topographic maps as the Blue Stones Mine.[47][48][49] This tunnel exposed a "five-foot vein of ore varying in values from $16 to $25 per ton."[46]

It was concluded that the “Guinn Mountain area has little or no economic potential.” Further, “ten samples collected in the area contained only negligible amounts of any metal. Samples from the Avalon placer claim, located on the South Fork [of] Middle Boulder Creek north of Guinn Mountain, and from the creek bottom were collected and panned; no gold was found.”

Rollins Pass as an historic railroad route

Early railroad endeavors

There were multiple prior efforts to build a railroad over Rollins Pass in the 19th century and all attempts were met with impassable engineering challenges, financing issues, or both: GHS, Jefferson, & Boulder County Railroad and Wagon Road (A.N. Rogers’ line) in 1867; U.P. in 1866; Kansas Pacific in 1869; Colorado Railroad (B. & M. subsidiary) in 1884—two tunnels located; Denver, Utah & Pacific in 1881 (construction started and tunnel located).[2]:27 The remains of the latter tunneling attempt can still be seen on the northern slope of the rock wall at Yankee Doodle Lake and the detritus from the attempted excavation of the tunnel was placed at the northernmost part of the lake where pulverized granite tailings can be seen rising out of the water.[14] These tailings were definitively from the 1880s tunneling efforts as they are not visible in the early stereoscopic images from the wagon road era of Yankee Doodle Lake; further, the attempted tunnel was not part of the later rail line that ultimately summited Rollins Pass.[2]:20

The Moffat Road over Rollins Pass

In the early 20th century, David Moffat, a Denver banker, established the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway with the intention of building a railroad from Denver toward Salt Lake City, Utah by way of a tunnel under the Continental Divide.[52][53][54][55] However, the railway only reached Craig, Colorado. This entire line from Denver to Craig was known as the Moffat Road.[2]:9

The line included a 23-mile stretch over the top of the Continental Divide, at Rollins Pass, with a two to four percent grade and switchbacks along many sections; the result was one of the highest adhesion (non-cog) standard-gauge railroads ever constructed in North America.[2]:9 This corridor over Rollins Pass was always intended to be temporary until what would later become the Moffat Tunnel was constructed and opened; therefore this overmountain route was constructed as cheaply as possible: using wooden trestles instead of iron bridges or high fills and wyes instead of turntables. Construction of this route was exceptionally dangerous and deadly: in a single day, 60 Swedish workers were killed when a powder charge exploded prematurely during the construction of Needle’s Eye Tunnel.[56]

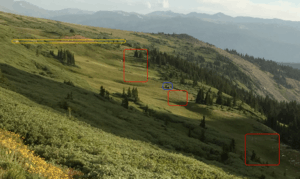

Along this route were three tunnels: Tunnel #31 (Sphinx Head Rock), Tunnel #32 (Needle's Eye Tunnel), and Tunnel #33 (the Loop Tunnel at Riflesight Notch).[57] All three tunnels today are either completely caved in or have had multiple partial cave-ins. Other notable landmarks on the route included the Riflesight Notch Loop, located at Spruce Mountain:[58] a 1.5 mile loop where trains crossed over a trestle, made a ~90 degree gradual turn to descend 150 feet, and passed through Tunnel #33 underneath the trestle.[59]

A rail station, Corona, was established at the summit of the pass, with a red brick dining hall, weather station, power station, and lodging. In summers, the train ride from Denver to Corona was advertised as a trip, "from sultry heat to Colorado's north pole;" tourists could stand in snowdrifts in the middle of July or August.[60][61][62][63][64][65] Tours launched from the Moffat Depot,[66] a small building constructed in the Georgian Revival style, featuring two-story tall windows, intricate exterior brickwork, and roofline pommels.[67] This building, located several city blocks northwest from Denver Union Station, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976,[68] and laid dormant for many decades after it was shuttered in 1947;[69] in 2015, it was made the focal point of a senior living community center, after it was meticulously restored.

Weather and operational difficulties

Despite the fact that the line was enclosed in almost continuous snowsheds (wooden tunnels) near the summit of the pass, trains were often stranded for several days (and in some cases up to 30 days)[70] during heavy snowstorms because snow could fall or be blown through the wood planking of the sheds. Delays affected the timeliness of both newspaper and postal mail deliveries. Coal smoke and toxic gasses collected in the snowsheds causing temporary blindness, loss of consciousness, and sometimes death.[14][70] Workers on the Moffat Road had an adage: "There's winter and then there's August."[14] It was these heavy snowstorms that led to the financial demise of the Moffat Road and served as the incentive for construction of a permanent railroad tunnel through the Rocky Mountains and into Middle Park.

Following scuba dives, no evidence exists that locomotive or wreck debris rests at the bottom of Yankee Doodle Lake or Jenny Lake.[2] However, many derailments, wrecks of Mallet locomotives, and/or the loss of portions of rail manifests occurred on both sides of the pass:[59]

| Side of Rollins Pass | Specific location | Equipment involved | Crew deaths | Passenger deaths† | Crew injuries | Passenger injuries | Date | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | on a curve just above Antelope | Mallet No. 201, 10 coal cars, and caboose[71][72][73][74] | 4 | N/A | 1 | - | January 1910 | brake failure |

| East | unknown | rotary[75] | - | N/A | - | - | February 1913 | derailment |

| East | near Jenny Lake | rotary and several cars[75] | - | N/A | - | - | March 1913 | avalanche |

| East | Dixie siding | box car with stuck brake[76] | 1 | N/A | - | - | November 1913 | fall |

| East | Bogen sheds near Jenny Lake | rotary[77][78][79][80] | 1 | N/A | 2 | - | January 1915 | brake failure |

| West | Ranch Creek Wye | freight train[81] | - | N/A | - | - | December 1915 | derailment |

| West | Old Camp Six | 12 loaded coal cars, Mallet helper, caboose[82][83] | 0 | N/A | 0 | - | January 1917 | brake failure |

| West | Arrow | Engine 120 and the caboose from the rollback, above[82] | 0 | N/A | 0 | - | January 1917 | brake failure |

| West | Ranch Creek Wye | passenger train and rotary collision[84] | - | N/A | 2+ | 1 (first passenger injury)[85] | April 1917 | damaged rail leading to a collision |

| East | Spruce | freight train extra 118 and multiple coal cars[86][87] | 1 | N/A | 3 | - | April 1917 | brake failure |

| East | inside Needle's Eye Tunnel | freight train[88] | 0 | N/A | 0 | - | October 1917 | derailment |

| East | Yankee Doodle Lake | rotary and engine[89][90][91] | 3 | N/A | 2+ | - | December 1917 | avalanche |

| West | snowsheds at Corona | freight train[92] | 0 | N/A | 0 | - | October 1918 | derailment |

| East | unknown | wooden gondola railcar[2]:118 | 0 | N/A | 0 | - | 1909-1929 | derailment |

| East | Antelope | two engines and 10-23 coal cars[93][94][95][96][97][98] | 2 | N/A | - | - | December 1922 | brake failure and fatigue |

| West | Riflesight Notch Loop | Mallet No. 208 and tender[99][100][101] | 4 | N/A | 2 | - | February 1922 | avalanche |

| West | Ranch Creek Wye | two coaches[102] | - | N/A | - | - | July 1923 | derailment |

| West | Riflesight Notch Loop | Mallet No. 210 | - | N/A | - | - | 1924 | derailment |

| West | snowsheds at Corona | passenger train No. 2 and caboose[103][104] | 0 | N/A | 0 | - | October 1925 | fire |

The Moffat Tunnel

Several locations for the Moffat Tunnel were scouted prior to the selection of the present-day location; one possible location was identified at high altitude between Yankee Doodle Lake and the Forest Lakes.[106]

Plans to build a longer tunnel at a lower elevation were better planned and financed; the single-track Moffat Tunnel opened just south of Rollins Pass on Sunday, February 26, 1928. The Moffat Tunnel eliminated 10,800 degrees of curvature along the Rollins Pass route; the tunnel resulted in considerable time savings as well as money that was used for snow removal atop Rollins Pass.[105] After the first year of operations, an annual report to stockholders showed "marked savings in operating costs" by 24.86%. Savings were seen in other areas, including in fuel reductions ($89,074.45 savings; $1.3 million in 2018 when adjusted for inflation[107]), engine servicing ($156,188.89 savings); whereas gross tons per train hour increased by 34.84%.[108]

After the Moffat Tunnel opened, the tracks over Rollins Pass remained in place and were maintained at least as late as July 1929[109] as an emergency route. This emergency route was needed only once[110] for a several day-long closure: on Thursday, July 25, 1929, dry rot of wooden timbers caused a collapse and 75 feet of rock caved-in and blocked the Moffat Tunnel near the East Portal. It took until Tuesday, July 30, 1929 for the tunnel to be cleared of debris.[111][112] Permission to dismantle the rails on Rollins Pass was granted by the Interstate Commerce Commission on Saturday, May 18, 1935[110] and the rails were removed the following summer: the west side was cleared by Tuesday, August 11, 1936, and the east side 14 days later; contractors toiled non-stop, including overnight to remove both the rails and ties.[2]:67 A wye on the passing siding at the East Portal of the Moffat Tunnel is currently utilized for short-turning some modern services and marks the spot where the Rollins Pass line, if it still existed, would have merged into the modern route.

The route through the Moffat Tunnel became part of the mainline across Colorado for the Denver and Salt Lake Railroad, later the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, and now the Union Pacific Railroad. The Moffat Tunnel continues to be used for both the Amtrak's California Zephyr that provides service between Chicago, Illinois and Emeryville, California as well as for the seasonal Ski Train that operated between Denver and Winter Park from 1940 to 2009; in March 2015 and from 2017–present, the service was rebranded the Winter Park Express.

The pioneer bore used to originally construct the Moffat Tunnel was later converted into the Moffat Water Tunnel by Denver Water.[113]

Rollins Pass as an air route and navigational waypoint

In the era of powered flight, Rollins Pass provides an attractive way to cross the Continental Divide between west and east at a relatively low point for aircraft. Not only does the enroute airway radial, Victor Eight, cross the pass; but a rotating airway beacon was established in the mid-to-late 1940s and first appeared on aeronautical sectional charts in March 1948 as a star, indicating a beacon.[114][115] The beacon and its supporting infrastructure have since been removed due to the introduction of the Low-Frequency Radio Range systems to replace visual navigational aids. The rough road that was once used to service and reach Beacon Peak at the Continental Divide, branches off of the Rollins Pass road, and is closed to all forms of motorized traffic per the current Motor Vehicle Use Maps.

Rollins Pass as an historic automobile road

Plans to convert Rollins Pass into an historic automobile road were first published in November 1949.[116] Several years later, on Saturday, September 1, 1956, Colorado lieutenant governor, Steve McNichols, opened Rollins Pass as a non-vital and seasonal recreational road.[2]:104 Each summer, from 1956-1979, Rollins Pass served as a complete road over the mountain pass for automobiles until a rock fall in Needle's Eye Tunnel in 1979 closed the path over the pass. In 1989, after several engineering studies and structural strengthening of Needle's Eye Tunnel were accomplished, the complete road was re-opened only to close permanently, due to another rockfall, in July 1990.[117][118]

Rollins Pass as a natural gas pipeline route

In the mid-1990s, Rollins Pass was closed for the installation of a 10-inch diameter Xcel Energy high-pressure natural gas pipeline.[119] The pipeline, not under marker,[120] still is in existence and uses the low pass to reach the Front Range by loosely following County Road 8 in Fraser, utilizing much of Ranch Creek towards the Middle Fork of Ranch Creek below Mount Epworth, climbing the pass near Ptarmigan Point, and following much of the old railbed past Corona at the summit of Rollins Pass. The pipeline continues across the railbed towards and under the twin trestles, down the old wagon route on the spine of Guinn Mountain, and then towards Eldora.[121]

Artifacts

Preservation of both prehistoric and the historic record

A majority of Rollins Pass is located within the boundaries of two national forests—Roosevelt National Forest and Arapaho National Forest—and as such, is federal land.[122] The Archaeological Resources Protection Act along with the Antiquities Act, among other federal and cultural laws, protects and makes it illegal to collect artifacts, including but not limited to: arrowheads, horseshoes, buttons, cans, glass or ceramic bottles, dishware and utensils, coal, railroad spikes, and telegraph poles from Rollins Pass. All artifacts—from the prehistoric to the historic‡—on the pass are objects of antiquity and are being studied and documented by universities and government agencies.[2]:12 The material record of Rollins Pass is illegally carried away each year in the backpacks of well-intentioned visitors who want a souvenir.[122][2]:12 Each artifact has important scientific and cultural value and theft harms the historical record.[122] Visitors are encouraged to preserve the area for future generations by leaving items in place and sharing photographs and GPS coordinates (if available) with researchers dedicated to telling the story of Rollins Pass and a web resource has been setup to aid with this project.[2]:127[123]

Enforcement

United States Forest Service Law Enforcement personnel and staff routinely patrol and enforce natural and cultural resources on Rollins Pass as well as in other areas within the National Forest System.[124][125]

Artifacts affecting the road prism

On both sides of Rollins Pass, the road prism contains both prehistoric and historic artifacts buried under the surface. Any improvements to the rough road through regrading, including paving, would first require extensive sectional archaeological excavations by the United States Forest Service. In several places, on or just under the surface, historical artifacts are covered with geotextile stabilization fabrics having characteristics that match the soil and permeability of the existing roadbed.[2]:119

Ghost towns, settlements, and gravesites

There are several ghost towns on or near Rollins Pass, the four most notable being Arrow, Corona, Eldora and the East Portal construction camp, and Tolland.[42][126] There are also at least a half-dozen other established settlements, dating back to both the wagon road and railroad eras, scattered across Rollins Pass.[2]

There are also several historic gravesites across Rollins Pass. One granite headstone at Arrow reads, "R.M. Smith | June 28, 1842 | Nov. 12, 1909." One marker near the Eldora Ski Area states that it holds two members of John C. Frémont's third expedition in 1845-1846, although this is disputed.[127][128]

Environment

Leave No Trace

Rollins Pass has unique floral, faunal, and riparian zones that spread across multiple Colorado counties; to best preserve the native environment of Rollins Pass, leave no trace and trail ethics apply to all visitors.[131] Trundling is discouraged for safety and environmental concerns as well as to preserve artifacts.[132][2]:125

Flora

Rollins Pass consists of several distinct floral environments including lodgepole pine and quaking aspen at lower elevations, and krummholz at tree line. Above tree line, the landscape consists largely of small perennial wildflowers, cryptobiotic soils, and alpine tundra. The latter being extremely fragile and if damaged, can take hundreds of years to recover.[129][130] Leaving the trail can cause erosion, land degradation, possible species extinction, and habitat destruction[130] and it is for these reasons vehicles, including off-road vehicles, are not allowed to leave the established road.[133][134] There are at least two marked revegetation areas on Rollins Pass: one at Yankee Doodle Lake; the other at the summit leading to the historic dining hall foundation.

Pine beetle epidemic

The mountain pine beetle epidemic, beginning in 1996 and continuing through present day, affects many forested areas in Colorado, including those on Rollins Pass. One out of every 14 trees in Colorado is dead.[135][136][137] Trees affected by the beetles contain 10 times less water than a healthy tree and crown fires can quickly spread.[138][139]

Fauna

The top predator in the area are black bears (Ursus americanus), generally below timberline; however, they occasionally venture above the krummholz. The bears prey on bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) and mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus), as well as yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris) in the region. Above timberline, pikas (Ochotona princeps) are common. At or below timberline, both elk (Cervus canadensis) and mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) are common. The presence of migratory bighorn sheep and other large game is the reason why Native Americans constructed sprawling yet intricate game drive complexes on Rollins Pass.[9]

The porcupine can be seen at all elevations on Rollins Pass, including at (and above) the summit. The porcupine begins its rounds at sunset, as it is nocturnal; this member of the rodent family also has the ability to adroitly climb trees.[2]:113

Among birds, the white-tailed ptarmigan (Lagopus leucurus) are present on Rollins Pass, especially above treeline. Their seasonal camouflage is effective in the summer against the exposed blocks of granite as well as against snow in the winter, rendering them virtually undetectable. Brown-capped rosy finches (Leucosticte australis), rock wrens (Salpinctes obsoletus), and pipits are also seen or heard at timberline and near the summit.

Riparian zones

Nutrient-rich ecosystems exist on Rollins Pass where water, and bodies of water, meet the alpine and subalpine tundras.[140]

Lakes

There are three lakes on the west side of Rollins Pass: Deadman's Lake, Pumphouse Lake, and Corona Lake. On the east side of Rollins Pass are King Lake, Yankee Doodle Lake, and Jenny Lake. Historically, Yankee Doodle Lake was referred to as Lake Jennie by John Quincy Adams Rollins, but modern archaeologists have re-interpreted this to be the modern day Yankee Doodle Lake;[2]:20 the railroad and period newspapers occasionally referred to this lake as Dixie Lake.[141] Also in the vicinity: Bob Lake, Betty Lake, the Forest Lakes, Skyscraper Reservoir, Lost Lake, and Woodland Lake.[142]

Creeks and rivers

On the west side, in addition to the Fraser River at the start of Rollins Pass are the following creeks: the South Fork of Ranch Creek, the Middle Fork of Ranch Creek (fed by Deadman's Lake), and Ranch Creek (fed by Pumphouse and Corona Lakes). On the east side of Rollins Pass, the South Fork of the Middle Boulder Creek is fed by Bob and Betty Lakes and Jenny Creek is fed by both Jenny and Yankee Doodle Lakes; further downstream, Antelope Creek feeds into Jenny Creek. The South Boulder Creek runs at the start of Rollins Pass on the eastern side; but first flows through Buttermilk Falls, a large 550-foot-long waterfall, near King Lake, visible from the summit of Rollins Pass.[2]:65[142]

Improvements

A summer 2006 project led by the United States Forest Service and having the participation of both environmental and user groups saw improvements made to wetlands, lakeshore, and upland habitats at Yankee Doodle Lake and Jenny Creek.[143][144] Fencing was installed to restrict vehicle travel to designated routes and improve degraded areas.[145] Before work could begin, sectional excavations by archaeologists took place to document the wagon road era settlements of the "Town of Yankee Doodle at Lake Jennie," located at present day Yankee Doodle Lake.[2]:20

Wildfires

In the summers, wildfire danger increases due to various environmental factors: low moisture, lightning strikes, high winds, and human-caused factors. As the pass is a recreational area, wildfires can also be caused by unmanaged, unattended, and/or uncontrolled campfires.

Fire restrictions

At present, the entirety of Rollins Pass is covered by Stage 1 Fire Restrictions:

Nature caused

- On Saturday, August 3, 1996, a lightning strike caused one of the eastern-most wooden trestles near the summit to catch fire; the blaze was extinguished by fire crews before the trestle’s integrity could be compromised.[152][153] The wooden trestle was likely saved by the use of coal-tar creosote applied to treat and preserve the wood, as part of the Bethell process.[2]:83

Human or equipment caused

- On September 27, 1915, Mart Wolf, owner of the Elk Creek Saloon, set fire to his establishment in the town of Arrow on the west side of Rollins Pass in the hopes of collecting $1,000 of insurance money. Due to high winds, the fire quickly spread and Arrow was all but snuffed out of existence.[2]:54–55[154][155][156]

- On Wednesday, October 30, 1918, a fire fanned by 40-mile-per-hour winds claimed several snowsheds and buildings at Corona, including the destruction of the Weather Bureau's observation station.[2]:38[157][158]

- In 1923, a train caused a wildfire on the east side of Rollins Pass on Giant's Ladder.[2]:80

- On Thursday, October 15, 1925, passenger train No. 2, including caboose, was completely destroyed by a fire in the Corona snowshed; the fire consumed about 400–500 feet of snowshed.[103][104]

- On Wednesday, January 26, 1927, the town of Rollinsville was nearly destroyed by a fire believed to have been started by a spark from a locomotive. Five buildings were destroyed and 20 guests in the Rollinsville hotel lost their personal belongings when the hotel burned to the ground.[159]

- On Wednesday, August 4, 2010, a plane crash on the east side of the pass caused a small wildfire.[160]

Climate

Seasons

Winter

Arctic conditions are prevalent during the winter, with sudden blizzards, high winds, and deep snowpack. High country overnight trips require gear suitable for −35° Fahrenheit or below. The subalpine region does not begin to experience spring-like conditions until June. Wildflowers bloom from late June to early August.[161]

Summer

Due to high-elevation above timberline in a backcountry setting, there is neither lightning protection nor lightning mitigation from sudden thunderstorms resulting in a high-risk, extremely dangerous situation for visitors.[162] The most suitable—but not best—refuge available from electrical storms would be in a metal-topped vehicle as it would serve as a mobile Faraday cage.[163]

Weather equipment and historical records

Historical

During the railroad era, a United States Weather Bureau observation station was mounted atop the large water tank at the townsite of Corona. Records show "the prevailing wind direction was west, the lowest temperature recorded was −30° Fahrenheit (in February 1910), and the most monthly snowfall was in March 1912 with 72.5 inches of snow."[2]:45

Present day

A small, solar-powered weather station exists on the west side of Rollins Pass, located above Ptarmigan Point.

Atmospheric pressure

While temperature, humidity, and other factors influence atmospheric pressure, the atmospheric pressure on the summit measures roughly 457 Torr (mmHg); while a standard atmospheric pressure measured at sea level is 760 Torr. At this pressure, many people, especially out-of-town visitors, can suffer from rapid dehydration and altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness.[164] Acute mountain sickness can progress to high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) or high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), both of which are potentially fatal.

Avalanches

Human-triggered and natural avalanches are possible anywhere on the pass and there have been three notable avalanches—all at Yankee Doodle Lake—on Rollins Pass:

Railroad era

- On Tuesday, January 27, 1914, sliding snow from Tunnel #32 "completely covered the track for a long distance" caused a multi-day blockage at or near Yankee Doodle Lake.[165]

- On Monday, December 10, 1917, an avalanche near Yankee Doodle Lake swept a rotary and assisting engine 150 feet off of the tracks. The engineer of the assisting engine was "scalded about the head so badly that the bones of the face were exposed and he is not expected to live." Other railroad workers died and several were injured.[89]

Post-railroad era

Backcountry skiers, snowshoers, and snowmobilers are advised to check daily avalanche forecasts, practice diligent terrain management, and always carry and know how to use rescue gear, including Emergency Position-Indicating Radio Beacons (EPIRBs).[166]

On Wednesday, November 28, 2001, two highly-experienced backcountry skiers triggered a sizable hard-slab avalanche. From the accident report, "The avalanche released from a southeast-facing slope and fell 600 vertical feet and stopped by crashing through the 10-inch thick ice of Yankee Doodle Lake. The displaced water resulted in a surge 10-12 feet tall along the south shore." The avalanche pushed both men into the lake and one survivor was sent 190 feet into the center of the lake. The survivor, suffering from hypothermia and frostbite, hiked to five miles to the Eldora Mountain Resort where he sought help.[167] The search involved ground crews, air crews, avalanche rescue dogs, and trained dive-rescuers with specialized rubber suits. The body of the second skier was found 91 feet offshore. Both skiers were well-equipped, including having avalanche transceivers.[168][169] Following the accident, each year in December, the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group holds a Joe Despres Memorial Dry Land Transceiver Training to include practices for using transceivers, along with avalanche courses and backcountry seminars.[170][171][172][173]

Access

General information and seasonal recreation

Rollins Pass is managed by the United States Forest Service as a recreational location and can be accessed from roads on both west and east sides. The entire road is unpaved (dirt and rock), has no guardrails, and has a speed limit of 20 MPH.[175] Current-year Motor Vehicle Use Maps (MVUMs) should be reviewed to determine which trails and roads are open to vehicles. Violators are subject to fines up to $5,000—"regardless of the presence or absence of signs" and operating a vehicle in wilderness areas is prohibited.[176][177][178][174][179]

There are no facilities, shops, restrooms, water fountains, trash receptacles, nor shelters located on either side of the pass.[180] The only exception is the Ärestua Hut, located on the northern side of Guinn Mountain at 11,000 feet on the east side of Rollins Pass. The small hut was constructed 49 years ago and is open year-round.[181][182] A series of hand-constructed stone windbreaks exist above timberline north of Needle's Eye Tunnel—these structures date to the railroad era on Rollins Pass and are not prehistoric. These windbreaks currently lack upper coverings or roofs and serve only as aerodynamic dampeners for wind and wind gusts.[183]

Winter

Both sides of the pass can be traveled by snowmobile when at least six inches of snow cover the road in the winter—generally beginning in late November or early December and lasting through early April.[184]

Spring

Both sides of the pass are closed in spring—including several weeks in June—to any form of motorized traffic: snowmobiles, automobiles, ATVs, or motorcycles for the prevention of road damage.[180]

Summer

Both sides of the pass can be traveled—in good weather—by motorized vehicles in the summer. Rollins Pass is scheduled open for vehicular summer traffic from June 15 through November 15; however, it is generally not possible given typical snowfall accumulations and slower melt rates in southerly-shaded areas, to drive higher than Sunnyside or Ptarmigan Point on the western side, or Yankee Doodle Lake on the eastern side before early-to-mid July.[185][186] The first high-country snowstorms bring fierce winds and create impassible snow drifts that are not plowed; this effectively puts higher landmarks—including the summit—out of reach as soon as late September or early October. On average, the near-annual existence of snow at or above timberline, ensures the road is only passable less than 90 days per year.[2]:10

Summer usage of the pass is currently classified as 'heavy' by the United States Forest Service; as such, parking can be very limited at designated parking sites.[185] While the route mostly has gentle grades with switchbacks between two and four percent and does not contain loose gravel, four-wheel drive higher-clearance vehicles fare better than two-wheel drive vehicles, particularly in certain technical sections: some areas on the east side have up to a 17.63% grade; the west side has some areas with a 15% grade.[187][188] In narrow sections, the vehicle heading downhill must yield to the vehicle traveling uphill.[189]

From the north or south (along the Continental Divide Trail)

The Continental Divide Trail crosses the summit of Rollins Pass from south to north; the trail bisects the former wye at Corona and takes hikers through the Indian Peaks Wilderness past the dining hall foundation at the summit.

From the east (near Rollinsville & Tolland)

The road up the pass on the eastern side from the Peak to Peak Highway (State Highway 119) begins at the East Portal road running west, parallel to South Boulder Creek and the current Union Pacific Railroad tracks, to the East Portal of the Moffat Tunnel, and then rises on the abandoned railroad grade from Giant's Ladder to the closed Needle's Eye Tunnel. From Rollinsville to East Portal, the road is an all-weather gravel road, with several chattery washboard sections, that can be traveled by regular automobiles. However, beginning at East Portal, at the formal start of Rollins Pass road (Forest Service Road 117), the road prism becomes very rough due to sustained sections of angular cobbles and potholes, the latter being several feet in size. The road has a level 2 road maintenance status described as "assigned to roads open for use by high-clearance vehicles" that includes the following attributes: "surface smoothness is not a consideration" and is "not suitable for passenger cars."[190][191][192][179]

This former railroad bed is open for 11.7 miles; two miles past Jenny Lake, there is a concrete-filled steel road gate with large rocks and berms approximately one half-mile before Needle's Eye Tunnel.[193][59] A rough trail continues around either side of the tunnel for nonmotorized transportation; the road is open for hiking and mountain biking beyond the barricaded portal of the tunnel toward the summit.

A majority of the lower portion of the east side of the pass is posted private property with no trespassing off either side of the road as the properties belong to Tolland Ranch, LLC and the Zarlengo Family Partnership, LLP as well as smaller land segments belonging to other entities.[194] Shortly before the Spruce Wye, the land ownership transitions to the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forest where it remains uninterrupted up to and including the summit and surrounding areas.

From the west (near Winter Park)

The road up the pass (County Road 80) on the western side from Winter Park starts from U.S. Highway 40 in Winter Park and has several sections of angular cobbles and potholes of varying dimensions, some several feet in size. The road has a level 2 road maintenance status described as "assigned to roads open for use by high-clearance vehicles" that includes the following attributes: "surface smoothness is not a consideration" and is "not suitable for passenger cars."[190][191]

The road is open for 14.4 miles and terminates at the summit parking area.[178] Exactly 0.15 miles before reaching the summit, capable vehicles can turn right onto County Road 80 and continue via Forest Service Road 501—this rough road rises above and bypasses the summit for another 1.8 miles before dead-ending overhead Yankee Doodle Lake at Guinn Mountain.[59]

A majority of the lower portion of the west side of the pass is private property belonging to Arrowhead Winter Park Investors, LLC and the Denver, City & County Board of Water Commissioners, known more commonly as Denver Water.[195] Shortly after the ghost town of Arrow and several miles before what was the Ranch Creek Wye, the land ownership transitions to the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forest where it remains uninterrupted up to and including the summit and surrounding areas.

Guided tours

- Winter: Guided winter snowmobile tours follow much of the summer road from Arrow and terminate shortly after Sunnyside (located further uphill and past the Riflesight Notch trestle). Winter tours "top out at nearly 12,000 feet"[196] but do not go higher than Ptarmigan Point and do not reach the summit at 11,676.79 feet.

- Summer: Guided summer off-road tours are also conducted on the west side of Rollins Pass; however, all tours are conducted on-road using off-road capable vehicles and any off-roading is strictly prohibited.[197]

Incidents and accidents

Due to hairpin turns, steep terrain, and inclement weather, there have been several incidents[198] and accidents, some fatal on or near the Rollins Pass road:

Non-motorized

- On Tuesday, March 19, 1968, a young hiker was rescued near the Riflesight Notch trestle after hiking from East Portal to Winter Park without snowshoes, skis, or adequate clothing.[199]

- On Wednesday, July 18, 2012, a woman was injured after losing her footing and sliding 200 feet down a snowfield where she crashed into rocks at the bottom of the slope. The injured woman was taken via a Flight for Life helicopter to Denver.[200]

- On Sunday, February 4, 2018, a backcountry skier fell, sustained multiple injuries—including broken bones, and became unconscious. His friend was able to phone for emergency services but a helicopter could not land due to 70 MPH winds and blowing snow. Rescuers could not arrive until 10 hours later.[201][202][203][204]

- On Saturday, August 4, 2018, a backcountry skier fell approximately 300 feet down Skyscraper Glacier on Rollins Pass, impacted rocks, and became unconscious. Search and rescue services were mobilized and the 23-year-old skier was able to hike back to the summit.[205]

Motorized

- On Saturday, October 8, 2011, a car crashed into the South Boulder Creek off of Rollins Pass road, the driver was pronounced dead at the scene and the passenger was taken to the hospital.[206]

- On Monday, February 18, 2013, a snowmobiler on the west side of Rollins Pass, lost control of his machine on a groomed trail and struck a tree where he was pronounced dead by search and rescue services.[207]

- On Sunday, August 16, 2015, two girls on ATVs, ages 11 and 12, went over a 150-foot cliff on Rollins Pass road; requiring the services of both an ambulance and a medical evacuation by helicopter.[208][209]

- On Saturday, May 5, 2018, search and rescue services were called for an ATV rollover accident on the east side of Rollins Pass.[210]

- There are several motor vehicles that have wrecked on Rollins Pass; yet these instances appear to have been done deliberately as no news articles seem to be associated with these wrecks. Four wrecks are still visible on the east side of Rollins Pass—one car and one snowmobile on the first leg of Giant's Ladder near the start of the Rollins Pass road; one car near Guinn Mountain closer to the summit; and one ATV directly off the summit, downslope from the old pergola, on the eastern side of the Continental Divide (recovered in mid-September 2018). On the west side of the pass, a wrecked snowmobile can still be found at the southern slopes of Mount Epworth near the shores of Deadman's Lake.[211]

Route and closures

The complete pass is open and accessible for snowshoeing, fatbiking, backcountry skiing, and cross-country skiing in the winter and to hikers, bicyclists, and horseback riders in the summer.[212][213][180][214][215][216][169][167][172][217]

For visitors in motor vehicles wishing to access and retrace the old railroad line, the majority of the route or right-of-way over the pass is open and intact with several exceptions.[218] Some of the railroad trestles have deteriorated (at Riflesight Notch), have been destroyed (trestle #72.83 on the west side, by the FAA [then the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA)] in 1953),[2]:83 or have been dismantled (trestles #51.00 and #54.48 on the east side). Per the current Motor Vehicle Use Maps, all extant trestles on the pass are closed to any form of motorized traffic, including motorcycles. Two railroad tunnels on Rollins Pass are completely caved-in: Tunnel #31 (Sphinx Head Rock) and Tunnel #33 (the Loop Tunnel at Riflesight Notch).[219][59] Closures also include sections leading to Tunnel #32, Needle's Eye Tunnel—a 170-foot-long[2]:120 high-altitude railroad tunnel used through 1928. The tunnel was open to automobiles from 1956-1979 for seasonal and inessential purposes. In 1979, the tunnel was closed due to rock falls; following a geologic engineering study in 1981, a Mine Safety and Health Administration study in 1985, engineering design work in 1986, and repair work in August 1987,[220] the tunnel was re-opened in 1989.[2]:10[221] The following year, in July 1990, several thousand pounds of rock fell from the crown of the tunnel, injuring a United States Navy veteran and Denver firefighter resulting in a below-knee amputation.[222][2]:10[223][224] Since then, the tunnel was sealed by Boulder County along with the United States Forest Service and rockfalls continue to occur at both the crown and shoulder of the tunnel.[2]:120[225] In November 1990, the post-accident engineering report cited restoration errors and faulty work: design specifications were not consistently followed, rock bolts were incorrectly spaced, and gravity and seasonal temperature variations were also listed as factors in the accident.[226]

In 2002, the James Peak Wilderness and Protection Area Act (Public Law 107-216) was passed by Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush. The act amended the Colorado Wilderness Act of 1993 and designated lands within both the Arapaho National Forest and the Roosevelt National Forest as the James Peak Wilderness area and added lands to the Indian Peaks Wilderness, establishing these lands as federally protected territory. The act contained an administrative provision:

If requested by one or more of the Colorado Counties of Grand, Gilpin, and Boulder, the Secretary shall provide technical assistance and otherwise cooperate with respect to repairing the Rollins Pass road in those counties sufficiently to allow two-wheel-drive vehicles to travel between Colorado State Highway 119 and U.S. Highway 40. If this road is repaired to such extent, the Secretary shall close the motorized roads and trails on Forest Service land indicated on the map entitled ‘Rollins Pass Road Reopening: Attendant Road and Trail Closures’, dated September 2001.[227]

To date, no repairs have been made: Gilpin and Grand counties have requested to open the road; however, the difficulties and expenses of making improvements to the road, including coordination of maintenance and re-introduced liabilities—coupled with intractable disputes surrounding the 1990 accident in the tunnel, have become contentious and ongoing issues.[228][192][229]

Aviation

Airway Victor Eight

Rollins Pass is traversed by a low altitude enroute airway radial, Victor Eight, the width of the airway is 4 nautical miles on either side of the centerline which skirts the summit of the pass.[230][3][114] Pilots have recommended to avoid the area in bad weather due to extreme downdrafts, mountain waves, and turbulence on the east side of the pass.[231][232]

Emergency landing zone

A non-illuminated summer emergency backcountry helicopter landing zone exists at the summit, placed sometime between September 1999 and October 2005.[233]

Rotating airway light beacon (Beacon 82)

A rotating airway light beacon (Beacon 82 on aeronautical charts), was placed very near the summit of Rollins Pass atop what was then later termed Beacon Peak, in the mid-to-late 1940s at an approximate elevation of 12,080 feet.[234][235] The glass-domed lighted beacon rotated six times per minute, marking the airway between Los Angeles and Denver, and it held a two-million candlepower electric lamp with a 24-inch parabolic reflector.[236] The beacon was removed in the late-1960s and is currently in storage (not on display) at the Pioneer Village Museum in Hot Sulphur Springs, Colorado; however an 11 foot by 9 foot concrete foundation remains at the top of the peak along with the leg stubs used for the beacon's lattice tower.

Accidents and incidents

There have been many documented airplane and helicopter crashes on and near Rollins Pass:

- On Sunday, August 21, 1949, two people were killed instantly when their plane crashed on Rollins Pass.[237]

- On Wednesday, January 6, 1954, a single engine airplane—a Beechcraft C35—with a tail number of N792D, crashed on a shoulder of Guinn Mountain near Yankee Doodle Lake on the east side of Rollins Pass.[238]

- On Saturday, March 3, 1962, a Beechcraft 35 with a tail number of N430B, crashed near Rollins Pass close to Jenny Creek.[239]

- On Tuesday, March 6, 1962, a Bell UH-1 Iroquois military helicopter with a tail number of AF91635, crashed near Rollins Pass close to Jenny Creek.[239]

- On Friday, January 24, 1964, a single engine airplane, with a tail number of N4351N, crashed in turbulent, cloudy, and stormy conditions near the Riflesight Notch Loop on Rollins Pass. One pilot and three passengers of the Cessna 195 were killed on impact and recovery did not occur until August 20 that year.[240]

- On Monday, July 11, 1966, a nonscheduled operation of an Alamo Airways De Havilland 104-6A, with a tail number of N1563V, impacted a mountainside in turbulent, cloudy, and stormy conditions on Rollins Pass. The crash of this dual engine plane occurred upslope of Deadman's Lake, opposite Mount Epworth at the crest of the Continental Divide.[241] Two crew and one passenger were killed.[242]

- On Saturday, January 3, 1970, a Cessna 172 with a tail number of N7104A, crashed into an alpine lake at "11,700 [sic] feet" near Rollins Pass, killing both aboard.[243][239]

- On Tuesday, December 14, 1971, a single engine AT6 trainer crashed near Rollins Pass, killing the pilot.[244][245][246][247]

- On Wednesday, December 30, 1998, a single engine airplane—a Piper PA-28 Cherokee—made an unplanned forced landing on the east side of Rollins Pass in the midst of extreme wind and low visibility conditions. A cross-country skier was able to phone for a rescue, conducted by snowmobile, of the two passengers and one pilot who were injured; yet all three survived and were released from the hospital that evening.[216][248][249][250][251]

- On Sunday, July 30, 2006, a single engine airplane, with a tail number of N5232X, crashed in clear conditions on Rollins Pass, approximately equidistant from Bob, Betty, and King Lakes.[252] The two occupants of the 1969 American Champion 7KCAB were killed on impact.[253][254]

- On Wednesday, August 4, 2010, a single engine airplane, with a tail number of N8974A, crashed in clear conditions on Rollins Pass, near Jenny Creek, southeast of Yankee Doodle Lake. All three occupants of the 1951 Beechcraft C35 airplane were killed on impact.[160][255]

In popular culture

Film, music, and books

- Country music artist, Tracy Byrd, recorded a music video for the 1996 single, Big Love, which featured sights on the west side of Rollins Pass, including: Ptarmigan Point, Mount Epworth, Deadman’s Lake, Riflesight Notch trestle, and more. The album cover pictures the artist himself in front of a scenic backdrop that can be seen at the summit of Rollins Pass, looking northeast; the back of the album features the artist holding his guitar while seated on a rock outcropping near the railroad-era dining hall foundation at the summit.[256]

- The Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer 1925 silent film, The White Desert, starring Claire Windsor as Robinette McFarlane and Pat O'Malley as Barry Houston was filmed on Rollins Pass in the winter of 1922 and released to the public on Monday, May 4, 1925. The film features moving pictures of long trains ascending Riflesight Notch trestle and of rotary snowplows in action between Ptarmigan Point and the summit. The railroad imagery is displayed only at both the beginning and the end of the movie with dramatic scenes (mostly indoor or pseudo-outdoor) and both dialogue intertitles and expository intertitles filling most of the film's runtime. The film is considered to be rare and has historical significance due to the footage of trains and rotaries operating on Rollins Pass.[257]††

- The 1928 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer silent drama film, The Trail of '98, was filmed in part on Rollins Pass as well as inside the Moffat Tunnel using specialized lighting. The film was directed by Clarence Brown and starred Harry Carey as Jack Locasto.[258][259][260][261][262][263][264][265][266][267][268][269]

- In the late 1920s, movie producers scouted Rollins Pass as a possible location for a third film.[270]

- On Saturday, November 3, 2012, Colorado State University archaeology professor Dr. Jason M. LaBelle and colleague Dr. Pete Seel debuted their documentary film, Stone and Steel at the Top of the World which describes the ancient hunters of the Colorado high country as well as the Moffat Road railway. As part of a Rollins Pass Mini-Film Fest event held at Colorado State University, the documentary was shown prior to a rare screening of The White Desert in Fort Collins, Colorado. This occasion marked the first time Reginald Barker's silent film had been shown since 1978.[271]

- On Saturday, May 12, 2018, Colorado State University archaeology professor Dr. Jason M. LaBelle along with the authors of multiple archaeological and research-based publications[272] on Rollins Pass, B. Travis Wright MPS and Kate Wright MBA, held a book launch event and presentation for Rollins Pass titled, Rollins Pass: Through the Lens of Time that included an encore screening of Dr. LaBelle's documentary film, Stone and Steel at the Top of the World as well as a rare screening of The White Desert at the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Littleton, Colorado.[273] At the event, as a central part of the authors' founding movement preserverollinspass.org, the authors discussed their efforts to build a GPS database of prehistoric and historic artifacts that will be made available for the benefit of archaeologists and land managers. They also revealed The John Trezise Archive for Rollins Pass Imagery—the "world's largest collection of Rollins Pass imagery for non-commercial use that is crowd-sourced, completely searchable and available to the public, and secured from loss."[274][275]

- The 2018 Peak to Peak Chorale's spring musical told "the tale of a train trapped for days by a spring blizzard atop Rollins Pass in the 1900s." The singers, musicians, and actors portrayed the passengers and crew that departed from The Stage Stop (in Rollinsville, Colorado) and became stranded when a huge rotary snowplow stopped working.[272]

Places and landmarks

- Some ski runs (and two chairlifts) at the nearby Winter Park Resort are named after Rollins Pass itself (Rollins Ridge, Corona Way), features on Rollins Pass (Riflesight Notch, Rainbow Cut, Needle's Eye, Phantom Bridge, Sunnyside), or are inspired by general railroad terminology (Runaway, Trestle, Boiler, Coupler, Railbender, Derailer, Sidetrack, Gandy Dancer, Iron Horse, Golden Spike, Brakeman, Vista Dome, Roundhouse, Zephyr).[276]

- Winter Park Resort's summer downhill mountain bike park is called Trestle.[277]

- Some of Winter Park Resort's buildings and services infrastructure are named after features on Rollins Pass (Mount Epworth), the neighboring Moffat Tunnel (West Portal), and general railroad terminology (Zephyr).[278]

- Two ski runs at the nearby Eldora Ski Resort are named after Rollins Pass: Corona and Corona Road along with the Corona Lift chairlift.[279]

Recreation

- For the past 52 years—since July 1966, the Epworth Cup has been one of the nation's longest-running downhill skiing races held annually in early-to-mid July on Mount Epworth.[119][280][281]

- On Thursday, May 10, 2018, it was announced that the Indian Peaks Traverse, a 60+ mile single-track trail open only to "hikers, bi[cyclists], horseback riders and any other form of non-motorized transport" will traverse a portion of Rollins Pass and is slated for a soft-opening in 2022.[282][283]

Science and archaeology

- In July 2016, the United States Forest Service held a Passport in Time project on Rollins Pass where volunteers joined "Heritage Program staff from the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests/Pawnee National Grassland (ARP) for an archaeological survey along the known trajectory of Moffat [R]oad."[284][2]:121

See also

Notes

- †.^ No passenger lives were lost during the years Rollins Pass served as a railroad; the Passenger deaths column reflects this fact with a value of N/A for each row.[2]:68

- ‡.^ For archaeology projects where federal laws apply, patterned cultural activity or features older than 50 years are considered historic.[285]

- ††.^ Otto Perry's Moffat Route DVD, released on July 13, 2006, contains select rotary footage from The White Desert.

References

- 1 2 "Rollins Pass". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Wright, B. Travis; Wright, Kate (2018). Rollins Pass. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1467127714.

- 1 2 3 "SkyVector: Flight Planning / Aeronautical Charts". skyvector.com.

- 1 2 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- 1 2 "BEFORE THE PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF COLORADO * * * * * - PDF". docplayer.net.

- 1 2 "Evaluation" (PDF). www.phmsa.dot.gov.

- 1 2 "NPMS Public Viewer". pvnpms.phmsa.dot.gov.

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 LaBelle, Jason M. & Pelton, Spencer R. "Communal hunting along the Continental Divide of Northern Colorado: Results from the Olson game drive (5BL147)", 2013

- ↑

- ↑ "GNIS Detail - Rollins Pass". geonames.usgs.gov.

- ↑ "Quillen: Name that pass". April 15, 2010.

- ↑ Griswold, P.R. "The Moffat Road"

- 1 2 3 4 Bollinger, Rev. Edward T., "Rails that climb"

- ↑ "Rollins Pass Game Traps". Atlas Obscura.

- ↑ "Presentation explores hunting practices of Native Americans".

- ↑ Faris, Peter (February 14, 2015). "Rock Art Blog: STONE BLINDS AND DRIVELINES - ROLLINS PASS, CO:".

- ↑ "Data" (PDF). dspace.library.colostate.edu.

- ↑ Alford, Paul (March 25, 2008). "Yankee Doodle Lake OHV Repairs Project Monitoring and the Preliminary Testing of 5BL370.1". United States Forest Service. Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests and Pawnee National Grassland: 1–32.

- ↑ "Colorado became the 38th state to join the Union, August 1, 1876".

- 1 2 "BLM Cultural Resource Series: Colorado-Cultural Resources Series No. 2 (Chapter 6)". www.nps.gov.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot October 10, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot March 21, 1940 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 "Steamboat Pilot November 1, 1945 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot December 26, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot February 20, 1918 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Boulder Daily Camera June 22, 1894 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 "Trinidad Enterprise August 15, 1873 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Daily Register Call July 1, 1873 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Golden Weekly Globe August 9, 1873 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot June 30, 1926 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain News July 22, 1870 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Colorado Springs Gazette July 29, 1876 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Daily Register Call September 19, 1872 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot June 4, 1924 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot June 15, 1939 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot July 4, 1930 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot June 15, 1939 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot June 4, 1924 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot September 6, 1922 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Rollins Pass and the Moffat Tunnel". EllensPlace.net. February 26, 1928. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Microsoft Word - Report Cover_Final.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot April 14, 1955 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Rollins or Corona - What shall it be called? - Grand County History Stories". stories.grandcountyhistory.org.

- ↑ The Mining American, Volume 46. Industrial Reporter Company. 1902. p. 338.

- 1 2 Mining Reporter, Volume 54. Mining Reporter Publishing Company. 1906. p. 501.

- ↑ A., Horton, John D. San Juan, Carma (April 30, 2018). "Prospect- and Mine-Related Features from U.S. Geological Survey 7.5- and 15-Minute Topographic Quadrangle Maps of the United States". mrdata.usgs.gov. doi:10.5066/F78W3CHG.

- ↑ https://store.usgs.gov/assets/MOD/StoreFiles/DenverPDFs/24K/CO/CO_East_Portal_1958_geo.pdf

- ↑ "The National Map - Advanced Viewer". viewer.nationalmap.gov.

- ↑ "Summit of Rollin's Pass :: Lithograph Collection". Digitalcollections.ppld.org. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Acclaimed Western Photographers ~ Louis Charles McClure". denverlibrary.org. September 22, 2014.

- ↑ "Leadville Daily Herald July 19, 1884 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Colorado Transcript April 22, 1926 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Aspen Daily Times October 29, 1891 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Oak Creek Times October 6, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot October 8, 1953 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Estes Park Trail May 4, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Locomotive Engineers Journal". Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers. July 30, 2018 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bollinger, E. T. & Crossen, Forrest "The Moffat Road (Former 'Hill' Route): A Self-Guiding Auto Tour"

- ↑ "Tourists rode train to 'the top of the world'".

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot July 26, 1911 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot September 22, 1909 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Yampa Leader July 24, 1925 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot April 7, 1909 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Yampa Leader July 24, 1925 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot November 6, 1947 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Restored Moffat depot part of luxury residences for seniors in Denver". March 2, 2015.

- ↑ "NPGallery Asset Detail". Npgallery.nps.gov. 1976-10-22. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Moffat Station, Denver Colorado".

- 1 2 "Info" (PDF). www.rockymtnrrclub.org.

- ↑ "Middle Park Times". Middle Park Times. June 3, 1910. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel January 21, 1910 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Aspen Democrat-Times January 20, 1910 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Montrose Daily Press January 20, 1910 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 "Moffat County Courier March 6, 1913 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel November 28, 1913 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Middle Park Times January 22, 1915 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Moffat County Courier January 21, 1915 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot January 20, 1915 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Moffat County Courier January 21, 1915 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Craig Empire December 29, 1915 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 "Middle Park Times January 19, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Routt County Republican January 19, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel April 6, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Craig Empire April 11, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "DRGW.Net - ICC472". www.drgw.net.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel April 27, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Oak Creek Times October 26, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 "Moffat County Courier December 13, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Oak Creek Times December 21, 1917 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot December 26, 1940 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Craig Empire November 6, 1918 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel January 19, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Yampa Leader March 2, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Moffat County Bell December 29, 1922 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Oak Creek Times March 3, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel March 2, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Craig Courier December 28, 1922 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel February 24, 1922 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Moffat County Bell February 24, 1922 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Craig Courier February 23, 1922 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel July 6, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 "Yampa Leader". Yampa Leader. October 16, 1925. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- 1 2 "Steamboat Pilot". Steamboat Pilot. October 21, 1925. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- 1 2

- ↑ "Routt County Sentinel January 24, 1919 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "US Inflation Calculator". US Inflation Calculator.

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot June 7, 1929 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Holy Cross Trail July 6, 1929 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 "Craig Empire Courier May 22, 1935 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Craig Empire July 31, 1929 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Railway Age". Simmons-Boardman. July 1, 1929 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Title and blank for printing.doc" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- 1 2 "Chart_Users_Guide.book" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Denver, CO - March 1948".

- ↑ "Steamboat Pilot November 3, 1949 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Rollins Pass 4x4 Trail - Colorado - Off-Road Magazine". September 27, 2006.

- 1 2 "Epworth competition is serious only about the enjoyment of ski racing". July 13, 2014.

- ↑ "PHMSA: Stakeholder Communications: Markers". primis.phmsa.dot.gov.

- ↑ "NPMS Public Viewer". pvnpms.phmsa.dot.gov.

- 1 2 3 "Brochure" (PDF). www.chicora.org.

- ↑ "Contact an Archaeologist - Preserve Rollins Pass".

- ↑ "Law Enforcement and Investigations - US Forest Service". www.fs.fed.us.

- ↑ "Wildland fires: Inside an investigation".

- ↑ Guyer, John Brownlee (1995). Rails over Hell Hill [The Moffat Road] (Motion picture (1950s)). Rollins Pass, Colorado: Wainwright, Arthur E.

- ↑ "Dead men at Boulder County's Eldora tell conflicting tales".

- ↑ "Search continues for identities of 'Fremont's men'".

- 1 2

- 1 2 3

- ↑ "Arapaho & Roosevelt National Forests Pawnee National Grassland - Forest Lakes Trailhead". United States Forest Service.

- ↑ "Look Before You Trundle - Outside Online". outsideonline.com. July 7, 2011.

- ↑ "WTG: East Rollins Pass - Stay The Trail". staythetrail.clubexpress.com.

- ↑ "WTG: South Sulphur / West Rollins Pass - Stay The Trail". staythetrail.clubexpress.com.

- ↑ "It's not your imagination. More trees than ever are standing dead in Colorado forests". February 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Documents" (JPG).

- ↑ "Forest Health: Mountain Pine Beetle - Rocky Mountain National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- ↑ "Mountain pine beetle effects on fire behavior – Research Highlights - US Forest Service Research & Development". www.fs.fed.us.

- ↑ "Field guide to diseases & insects of the Rocky Mountain Region" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Riparian Areas Environmental Uniqueness, Functions, and Values | NRCS". Nrcs.usda.gov. 1996-08-11. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Palisade Tribune May 25, 1923 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- 1 2 E.J. Young (2012-02-10). "Geologic map of the East Portal Quadrangle, Boulder, Gilpin, and Grand counties, Colorado". Pubs.er.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Rising Sun/USFS To Protect Jenny Creek Wetlands". August 23, 2006.

- ↑ "Louisville Times August 30, 2006 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection". www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ↑ "fall2006.pub" (PDF). Retrieved 2018-07-30.

- ↑ "Stage 1 Fire Restrictions - Grand County Emergency Information Portal". gcemergency.com.

- 1 2 "Data" (PDF). www.fs.usda.gov.

- ↑ "Fire Bans & Danger". www.coemergency.com.