Breckenridge, Colorado

| Breckenridge, Colorado | |

|---|---|

| Home Rule Municipality | |

Main Street in Breckenridge | |

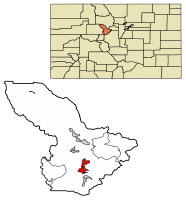

Location of Breckenridge in Summit County, Colorado | |

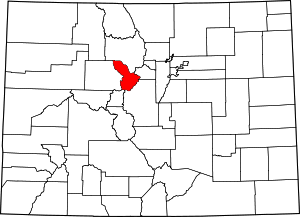

Breckenridge, Colorado Location in the contiguous United States | |

| Coordinates: 39°29′59″N 106°02′36″W / 39.499619°N 106.043292°WCoordinates: 39°29′59″N 106°02′36″W / 39.499619°N 106.043292°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Colorado |

| County | Summit County[2] |

| Established | November 1859 as Breckinridge |

| Incorporated | March 3, 1880[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Home Rule Municipality[2] |

| • Mayor | Eric Mamula |

| Area[4] | |

| • Total | 5.99 sq mi (15.52 km2) |

| • Land | 5.99 sq mi (15.52 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 9,600 ft (2,926 m) |

| Population (2010)[5] | |

| • Total | 4,540 |

| • Estimate (2016)[6] | 4,896 |

| • Density | 817.23/sq mi (315.54/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP code | 80424[7] |

| Area code(s) | 970 |

| FIPS code | 08-08400 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0204681 |

| Website | www.townofbreckenridge.com |

Breckenridge is a Home Rule Municipality that is the county seat and the most populous municipality of Summit County, Colorado, United States.[8] The town population was 4,540 at the 2010 United States Census. The town also has many part-time residents, as many people have vacation homes in the area. The town is located at the base of the Tenmile Range.

Since ski trails were first cut in 1961, Breckenridge Ski Resort has made the town a popular destination for skiers. Summer in Breckenridge attracts outdoor enthusiasts with hiking trails, wildflowers, fly-fishing in the Blue River, mountain biking, nearby Lake Dillon for boating, white water rafting, alpine slides, and many shops and restaurants up and down Main Street. The historic buildings along Main Street with their clapboard and log exteriors add to the charm of the town. Since 1981, Breckenridge hosts the Breckenridge Festival of Film in September.[9][10] In January each year in the 21st century there is a Backcountry Film Festival.[11] That is held about the same time as the Ullr Fest, a week of celebrating snow and honoring the Norse god Ullr.[12] There are many summer activities, including an annual Fourth of July parade.

Name

The town of Breckenridge was formally created in November 1859 by General George E. Spencer. Spencer chose the name "Breckinridge" after John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, 14th Vice President of the United States, in the hopes of flattering the government and gaining a post office. Spencer succeeded in his plan and a post office was built in Breckinridge; it was the first post office between the Continental Divide and Salt Lake City, Utah.

However, when the Civil War broke out in 1861, the former vice president sided with the Confederates (as a brigadier general) and the pro-Union citizens of Breckenridge decided to change the town's name. The first i was changed to an e, and the town's name has been spelled Breckenridge ever since.[13]

History

Prospectors entered what is now Summit County (then part of Utah Territory) during the Pikes Peak Gold Rush of 1859, soon after the placer gold discoveries east of Breckenridge near Idaho Springs. Breckenridge was founded to serve the miners working rich placer gold deposits discovered along the Blue River. Placer gold mining was soon joined by hard rock mining, as prospectors followed the gold to its source veins in the hills. Gold in some upper gravel benches east of the Blue River was recovered by hydraulic mining. Gold production decreased in the late 1800s, but revived in 1908 by gold dredging operations along the Blue River and Swan River. The Breckenridge mining district is credited with production of about one million troy ounces (about 31,000 kilograms) of gold.[14] The gold mines around Breckenridge are all shut down, although some are open to tourist visits. The characteristic gravel ridges left by the gold dredges can still be seen along the Blue River and Snake River, and the remains of a dredge are still afloat in a pond off the Swan River.

Notable among the early prospectors was Edwin Carter, a log cabin naturalist who decided to switch from mining to collecting wildlife specimens. His log cabin, built in 1875, still stands today and has been recently renovated by the Breckenridge Heritage Alliance with interactive exhibits and a small viewing room with a short creative film on his life and the early days around Breckenridge.

Harry Farncomb found the source of the French Gulch placer gold on Farncomb Hill in 1878. His strike, Wire Patch, consisted of alluvial gold in wire, leaf and crystalline forms. By 1880, he owned the hill. Farncomb later discovered a gold vein, which became the Wire Patch Mine. Other vein discoveries included Ontario, Key West, Boss, Fountain, and Gold Flake.[15]:57

The Breckenridge Heritage Alliance reports that in the 1930s, a women's group in Breckenridge stumbled upon an 1880s map that failed to include Breckenridge. They speculated that Breckenridge had never been officially annexed into the United States, and was thus still considered "No Man's Land". This was completely false—official US maps did include Breckenridge—but these women created an incredibly clever marketing campaign out of this one map. In 1936 they invited the Governor of Colorado to Breckenridge to raise a flag at the Courthouse officially welcoming Breckenridge into the union—and he came. There was a big party, and the entire event/idea of Breckenridge being left off the map made national news. The "No Man's Land" idea later morphed into a new theme of Breckenridge being referred to as "Colorado's Kingdom", and the theme of the town's independent spirit is still celebrated to today during the annual "Kingdom Days" celebrations every June.

In December 1961, skiing was introduced to Breckenridge when several trails were cut on the lower part of Peak 8, connected to town by Ski Hill Road. In the 50-plus years since, Breckenridge Ski Resort gradually expanded onto Peak 9 and Peak 10 on the south end of town, and Peak 7 and Peak 6 to the northwest of town.

On November 3, 2009, voters passed ballot measure 2F by a nearly 3 to 1 margin (73%), which legalized marijuana possession for adults. The measure allows possession of up to an ounce of marijuana and also decriminalizes the possession of marijuana-related paraphernalia. Possession became legal January 1, 2010. Possession was still illegal by state law, however, until the passage of Colorado Amendment 64 in 2012. The measure was written mainly to be symbolic.[16]

Geography

Breckenridge is located at 39°29′11″N 106°02′37″W / 39.486445°N 106.043516°W.[17] According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 4.9 square miles (13 km2), all of it land. The ski area has a total area of 4.5 square miles (12 km2) of land. The elevation of Breckenridge is 9600 feet (2926 m) above sea level.

Climate

Breckenridge's climate is considered to be high-alpine with the tree line ending at 11,500 feet (3,500 m). The average humidity remains around 30% throughout the year.[18] At the elevation of the weather station, the climate could be described as a variety of a subarctic climate since summer means are above 50 °F (10 °C) in spite of the very cool nights. Winter lows are quite severe, but the days averaging around the freezing mark somewhat moderates mean temperatures.

| Climate data for Breckenridge, Colorado (1893–1978) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

71 (22) |

61 (16) |

69 (21) |

78 (26) |

85 (29) |

86 (30) |

90 (32) |

86 (30) |

77 (25) |

69 (21) |

60 (16) |

90 (32) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 29.6 (−1.3) |

30.2 (−1) |

36.7 (2.6) |

44.3 (6.8) |

53.4 (11.9) |

65.2 (18.4) |

70.2 (21.2) |

70.3 (21.3) |

63.9 (17.7) |

51.8 (11) |

40.4 (4.7) |

30.2 (−1) |

48.9 (9.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 0.4 (−17.6) |

1.2 (−17.1) |

8.4 (−13.1) |

16.6 (−8.6) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

37.3 (2.9) |

36.6 (2.6) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

10.2 (−12.1) |

0.4 (−17.6) |

18.1 (−7.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −40 (−40) |

−37 (−38) |

−38 (−39) |

−35 (−37) |

−6 (−21) |

3 (−16) |

10 (−12) |

22 (−6) |

7 (−14) |

−11 (−24) |

−26 (−32) |

−36 (−38) |

−40 (−40) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.49 (37.8) |

1.67 (42.4) |

1.79 (45.5) |

1.94 (49.3) |

1.67 (42.4) |

1.37 (34.8) |

2.39 (60.7) |

2.32 (58.9) |

1.48 (37.6) |

1.27 (32.3) |

1.37 (34.8) |

1.49 (37.8) |

20.26 (514.6) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 21.7 (55.1) |

21.5 (54.6) |

23.6 (59.9) |

23.2 (58.9) |

10.7 (27.2) |

1.8 (4.6) |

0.1 (0.3) |

0.0 (0) |

3.3 (8.4) |

12.6 (32) |

21.8 (55.4) |

23.3 (59.2) |

163.6 (415.5) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[19] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 51 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,657 | 3,149.0% | |

| 1900 | 976 | — | |

| 1910 | 834 | −14.5% | |

| 1920 | 796 | −4.6% | |

| 1930 | 436 | −45.2% | |

| 1940 | 381 | −12.6% | |

| 1950 | 296 | −22.3% | |

| 1960 | 393 | 32.8% | |

| 1970 | 548 | 39.4% | |

| 1980 | 818 | 49.3% | |

| 1990 | 1,285 | 57.1% | |

| 2000 | 2,408 | 87.4% | |

| 2010 | 4,540 | 88.5% | |

| Est. 2016 | 4,896 | [6] | 7.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[21] | |||

As of the census of 2000, there were 2,408 people, 1,081 households, and 380 families residing in the town. The population density was 486.4 people per square mile (187.8/km²). There were 4,270 housing units at an average density of 862.6 per square mile (333.1/km²). The racial makeup of the town was 95.56% White, 0.37% African American, 0.33% Native American, 1.04% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 1.12% from other races, and 1.54% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 5.44% of the population.

There were 1,081 households out of which 13.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 27.9% were married couples living together, 4.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 64.8% were non-families. 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 0.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.16 and the average family size was 2.61.

In the town, the population was spread out with 11.1% under the age of 18, 22.8% from 18 to 24, 45.3% from 25 to 44, 18.7% from 45 to 64, and 2.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females, there were 160.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 164.2 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $43,938, and the median income for a family was $52,212. Males had a median income of $29,571 versus $27,917 for females. The per capita income for the town was $29,675. About 5.2% of families and 8.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 1.7% of those under age 18 and none of those age 65 or over.

For 2009 the average price for a single family home in the Breckenridge area is $1,035,806 with a sold price per square foot of $314.00. For multifamily properties the average price is $560,689 with a sales price per square foot of $440. Land sales prices averaged $373,067.[22]

Events

Breckenridge holds public events throughout the year.

Winter

Every January, the International Snow Sculpture Championships are held in Breckenridge, where sculptors from around the world compete to create works of art from twenty ton blocks of snow. The annual winter Ullr Fest parade pays homage to the Norse god of snow Ullr. The Backcountry Film Fest began in the 21st century, which happens in January.[11] That is held about the same time as the Ullr Fest.[12]

Since winter of 2008-2009, the Freeway Terrain Park on Peak 8 hosts the Winter Dew Tour in December, featuring the biggest names in extreme snowboarding and skiing. Other events held on the mountain include the annual Imperial Challenge, Breck's version of a triathlon, The 5 Peaks, North America's longest ski mountaineering race, the Breck Ascent Series, with races up the mountain, as well as other competitions, festivals, and the annual Spring Fever month-long celebration at the end of the ski season with festivities and other celebrations around spring skiing.[23]

Summer and Fall

During the summer, Breckenridge is host to the National Repertory Orchestra and the Breckenridge Music Institute. Concerts are scheduled three to four nights a week. Full orchestra, ensembles, and contemporary artists perform at the Riverwalk Center, downtown near the Blue River. Several art fairs come to Breckenridge every summer, attracting many local artists and buyers. The town also puts on an annual Fourth of July celebration, featuring a parade in the morning and fireworks at night. In September each year since 1981, the Breckenridge Festival of film is held.[9][10]

Outdoor summer activities

Common activities include mountain biking and road biking, hiking, and fly fishing. For mountain biking, Breckenridge hosts innumerable trails such as the Peaks trail which connects Breckenridge and Frisco and the Flume Loops which explore the Highlands Area. The 9-mile (14 km) tarmaced Breckenridge to Frisco bike track parallels Highway 9 and is a popular ride. The large number of passes in Summit County also attract road bikers. Many biking and running races are held in the area during the summer months. The nearby fourteener Quandary Peak gains the most attention for hikers. Fly fishing is also popular. During the summer, a fun park is operated at Peak 8 base, connected to town by the BreckConnect Gondola, including such activities as zipline rides, the GoldRunner coaster, an Alpine Slide, Jeep tours, and scenic rides on the Colorado SuperChair.[24]

Notable people

Notable individuals who were born in or have lived in Breckenridge include:

- Edwin Carter (c.1830-1900), miner, naturalist[25]

- Jeff Cravath (1903-1953), football coach[26]

- John Lewis Dyer (1812-1901), Methodist circuit rider[27]

- Barney Ford (1822-1902), Colorado businessman and civil-rights pioneer

- Arielle Gold (1996- ), Olympic bronze medalist snowboarder[28]

- Taylor Gold (1993- ), Olympic snowboarder[28]

- Al Jourgensen (1958- ), singer-songwriter, producer[29]

- Heather McPhie (1984- ), U.S. Olympic freestyle/moguls skier[30]

- Monique Merrill (1969- ), mountain biker, ski mountaineer[31]

- J. R. Moehringer (1964- ), novelist, reporter[32]

- Helen Rich (1894-1971), novelist and journalist[33]

- Betsy Sodaro (1984- ), actress, comedian[34]

- Pete Swenson (1967- ), ski mountaineer[35]

- Belle Turnbull (1881-1970), poet[33]

- Katie Uhlaender (1984- ), U.S. Olympic skeleton racer[36]

- Codi Seaboldt (1992- ), Former Lacrosse Player & Coordinator, Marketing and Operations[37]

In popular culture

Breckenridge was the filming location of the 1989 comedy National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation and the town stood in for Aspen in Dumb and Dumber. Also, the music video for Tequila by Dan and Shay was filmed there.

See also

References

- ↑ "2014 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Places". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- 1 2 "Active Colorado Municipalities". State of Colorado, Department of Local Affairs. Archived from the original on 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ↑ "Colorado Municipal Incorporations". State of Colorado, Department of Personnel & Administration, Colorado State Archives. 2004-12-01. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- ↑ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 25, 2017.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". 2012 Population Estimate. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "ZIP Code Lookup". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original (JavaScript/HTML) on September 3, 2007. Retrieved September 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-06-15. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 1 2 "37th Annual Breckenridge Film Festival". Without A Box. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- 1 2 "About the Breck Film Fest". Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- 1 2 "Backcountry Film Festival returns Jan. 21 to Breckenridge". Summit Daily. Summit County, Colorado. January 11, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- 1 2 Donnell, Mackenzie (December 19, 2016). "Ullr Fest in Breckenridge". Best of Breckenridge. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Town History, Gold Dust to White Gold". Special Features. Town of Breckenridge. Archived from the original on 2007-02-09. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ A. H. Koschman and M. H. Bergendahl (1968) Principal Gold-Producing Districts of the United States. US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 610, p.116-117

- ↑ Voynick, S.M., 1992, Colorado Gold, Missoula: Mountain Press Publishing Company, ISBN 0878424555

- ↑ "Breckenridge Votes to Legalize Pot". CBS. 2009-11-03. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ http://townofbreckenridge.com/index.aspx?page=368

- ↑ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ↑ https://www.infoplease.com/science-health/weather/colorado-temperature-extremes

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Breckenridge Real Estate". General Market Reports. Andrew Biggin. Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2009-12-22.

- ↑ "Breckenridge Snow Sculptures". Breckenridge Real Estate – Snow Sculptures. Ron Shelton. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ↑ "What To Do". Breckenridge Resort Chamber. Retrieved September 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Edwin Carter Discovery Center". Breckenridge Heritage Alliance. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "Jeff Cravath". IMDb. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "Father Dyer United Methodist Church". fatherdyer.org. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- 1 2 Foltz, Sebastian (2015-03-06). "Steamboat Olympic snowboarders Taylor and Arielle Gold at home in Breckenridge". Summit Daily. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ Murphy, Tom (2012-06-12). "Ministry's Al Jourgensen on his ties to Colorado: living in Breckenridge, attending Greeley High School and his ill-fated attempt at a rodeo career". Westword. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ Frame, Andy (2005-04-09). "McPhie wins Landon Sawyer Bump Bash". Summit Daily. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ McClean, Page (2015-07-25). "Life on Two Wheels: Globetrotting with former adventure racer Monique Merrill". Summit Daily. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ Clarke, Norm (2010-01-05). "AN 'OPEN' DISCUSSION WITH JR MOEHRINGER". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- 1 2 Beaton, Gail M. (2012). Colorado Women: A History (book)

|format=requires|url=(help). Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 978-1607321958. - ↑ Porter IV, Miles (2012-08-30). "Hey, Spike! offers a plethora of personalities". Summit Daily. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ Lapides, Katie (2011-02-10). "Colorado's randonee king: Pete Swenson". Summit Daily. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "Katie Uhlaender". Team USA. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- ↑ "Codi Seaboldt". Codi Seaboldt. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

External links

![]()