Mont-Saint-Michel

| Le Mont-Saint-Michel | ||

|---|---|---|

| Commune | ||

The center of the commune (the mount itself) of Le Mont-Saint-Michel seen from the Couesnon. | ||

| ||

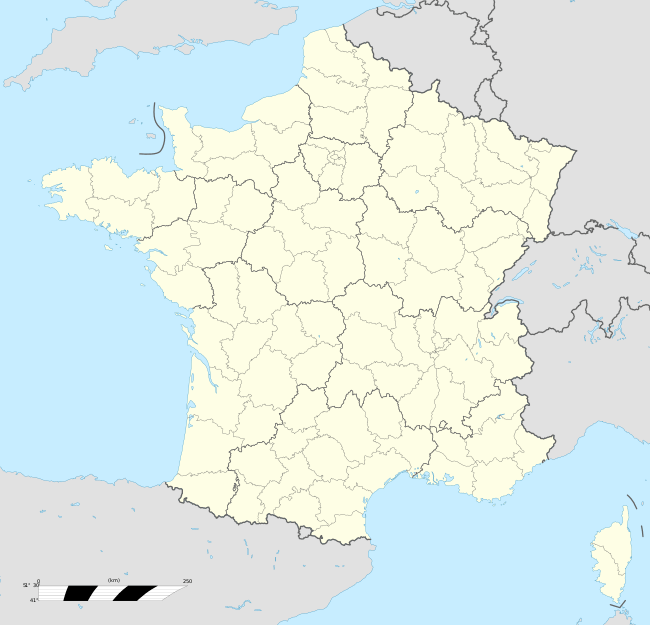

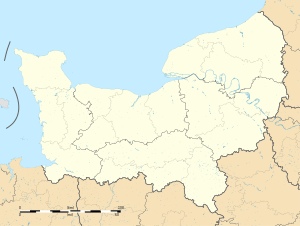

Le Mont-Saint-Michel Location within Normandy region  Le Mont-Saint-Michel | ||

| Coordinates: 48°38′10″N 1°30′41″W / 48.636°N 1.5114°WCoordinates: 48°38′10″N 1°30′41″W / 48.636°N 1.5114°W | ||

| Country | France | |

| Region | Normandy | |

| Department | Manche | |

| Arrondissement | Avranches | |

| Canton | Pontorson | |

| Intercommunality | Pontorson - Le Mont-Saint-Michel | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2014-2020) | Yann Galton | |

| Area1 | 0.97 km2 (0.37 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015)2 | 50 | |

| • Density | 52/km2 (130/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 50353 /50116 | |

| Elevation | 5–80 m (16–262 ft) | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

| UNESCO World Heritage site | |

|---|---|

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, vi |

| Reference | 80 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Area | 6,560 ha |

| Buffer zone | 57,510 ha |

Le Mont-Saint-Michel[1] (pronounced [mɔ̃ sɛ̃ mi.ʃɛl]; Norman: Mont Saint Miché, English: Saint Michael's Mount) is an island and mainland commune in Normandy, France.

The island[2] is located about one kilometer (0.6 miles) off the country's northwestern coast, at the mouth of the Couesnon River near Avranches and is 7 hectares (17 acres) in area. The mainland part of the commune is 393 hectares (971 acres) in area so that the total surface of the commune is 400 hectares (988 acres).[3][4]

As of 2015, the island has a population of 50.[5]

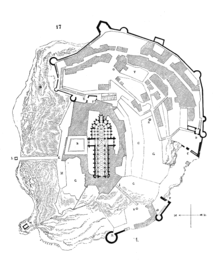

The island has held strategic fortifications since ancient times and since the 8th century AD has been the seat of the monastery from which it draws its name. The structural composition of the town exemplifies the feudal society that constructed it: on top, God, the abbey and monastery; below, the great halls; then stores and housing; and at the bottom, outside the walls, houses for fishermen and farmers.

The commune's position — on an island just a few hundred metres from land — made it accessible at low tide to the many pilgrims to its abbey, but defensible as an incoming tide stranded, drove off, or drowned would-be assailants. The Mont remained unconquered during the Hundred Years' War; a small garrison fended off a full attack by the English in 1433.[6] The reverse benefits of its natural defence were not lost on Louis XI, who turned the Mont into a prison. Thereafter the abbey began to be used regularly as a jail during the Ancien Régime.

One of France's most recognizable landmarks, visited by more than 3 million people each year, the Mont Saint-Michel and its bay are on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.[7] Over 60 buildings within the commune are protected in France as monuments historiques.[8]

Geography

Formation

Now a rocky tidal island, the Mont occupied dry land in prehistoric times. As sea levels rose, erosion reshaped the coastal landscape, and several outcrops of granite emerged in the bay, having resisted the wear and tear of the ocean better than the surrounding rocks. These included Lillemer, the Mont Dol, Tombelaine (the island just to the north), and Mont Tombe, later called Mont Saint-Michel.

Mont Saint-Michel consists of leucogranite which solidified from an underground intrusion of molten magma about 525 million years ago, during the Cambrian period, as one of the younger parts of the Mancellian granitic batholith.[9] (Early studies of Mont Saint-Michel by French geologists sometimes describe the leucogranite of the Mont as "granulite", but this granitic meaning of granulite is now obsolete).[10]

The Mont has a circumference of about 960 m (3,150 ft) and its highest point is 92 m (302 ft) above sea level.[11]

Tides

The tides can vary greatly, at roughly 14 metres (46 ft) between highest and lowest water marks. Popularly nicknamed "St. Michael in peril of the sea" by medieval pilgrims making their way across the flats, the mount can still pose dangers for visitors who avoid the causeway and attempt the hazardous walk across the sands from the neighbouring coast.

Polderisation and occasional flooding have created salt marsh meadows that were found to be ideally suited to grazing sheep. The well-flavoured meat that results from the diet of the sheep in the pré salé (salt meadow) makes agneau de pré-salé (salt meadow lamb), a local specialty that may be found on the menus of restaurants that depend on income from the many visitors to the mount.

Tidal island

The connection between the Mont Saint-Michel and the mainland has changed over the centuries. Previously connected by a tidal causeway uncovered only at low tide, this was converted into a raised causeway in 1879, preventing the tide from scouring the silt around the mount. The coastal flats have also been polderised to create pastureland, decreasing the distance between the shore and the island, and the Couesnon River has been canalised, reducing the dispersion of the flow of water. These factors all encouraged silting-up of the bay.

On 16 June 2006, the French prime minister and regional authorities announced a €164 million project (Projet Mont-Saint-Michel)[12] to build a hydraulic dam using the waters of the Couesnon and the tides to help remove the accumulated silt, and to make Mont Saint-Michel an island again. The construction of the dam began in 2009. The project also includes the removal of the causeway and its visitor car park. Since 28 April 2012, the new car park on the mainland has been located 2.5 kilometres (1.6 miles) from the island. Visitors can walk or use shuttles to cross the causeway.

On 22 July 2014, the new bridge by architect Dietmar Feichtinger was opened to the public. The light bridge allows the waters to flow freely around the island and improves the efficiency of the now operational dam. The project, which cost €209 million, was officially opened by President François Hollande.[13]

On rare occasions, tidal circumstances produce an extremely high "supertide". The new bridge was completely submerged on 21 March 2015 by the highest sea level for at least 18 years, as crowds gathered to snap photos.[14]

History

The original site was founded by an Irish hermit, who gathered a following from the local community. Mont Saint-Michel was used in the sixth and seventh centuries as an Armorican stronghold of Gallo-Roman culture and power until it was ransacked by the Franks, thus ending the trans-channel culture that had stood since the departure of the Romans in 460. From roughly the fifth to the eighth century, Mont Saint-Michel belonged to the territory of Neustria and, in the early ninth century, was an important place in the marches of Neustria.

.jpg)

Before the construction of the first monastic establishment in the 8th century, the island was called Mont Tombe (Latin: tumba). According to a legend, the archangel Michael appeared in 708 to Aubert of Avranches, the bishop of Avranches, and instructed him to build a church on the rocky islet.[15]

Unable to defend his kingdom against the assaults of the Vikings, the king of the Franks agreed to grant the Cotentin peninsula and the Avranchin, including Mont Saint-Michel traditionally linked to the city of Avranches, to the Bretons in the Treaty of Compiègne (867). This marked the beginning of a brief period of Breton possession of the Mont. In fact, these lands and Mont Saint-Michel were never really included in the duchy of Brittany and remained independent bishoprics from the newly created Breton archbishopric of Dol. When Rollo confirmed Franco as archbishop of Rouen, these traditional dependences of the Rouen archbishopric were retained in it.

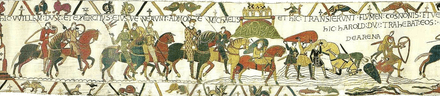

The mount gained strategic significance again in 933 when William I Longsword annexed the Cotentin Peninsula from the weakened Duchy of Brittany. This made the mount definitively part of Normandy, and is depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, which commemorates the 1066 Norman conquest of England. Harold Godwinson is pictured on the tapestry rescuing two Norman knights from the quicksand in the tidal flats during a battle with Conan II, Duke of Brittany. Norman ducal patronage financed the spectacular Norman architecture of the abbey in subsequent centuries.

In 1067 the monastery of Mont Saint-Michel gave its support to William the Conqueror in his claim to the throne of England. This he rewarded with properties and grounds on the English side of the Channel, including a small island off the southwestern coast of Cornwall which was modelled after the Mount and became a Norman priory named St Michael's Mount of Penzance.

During the Hundred Years' War, the Kingdom of England made repeated assaults on the island but were unable to seize it due to the abbey's improved fortifications. The English initially besieged the Mont in 1423–24, and then again in 1433–34 with English forces under the command of Thomas de Scales, 7th Baron Scales. Two wrought-iron bombards that Scales abandoned when he gave up his siege are still on site. They are known as les Michelettes. Mont Saint-Michel's resolute resistance inspired the French, especially Joan of Arc.

When Louis XI of France founded the Order of Saint Michael in 1469, he intended that the abbey church of Mont Saint-Michel become the chapel for the Order, but because of its great distance from Paris, his intention could never be realised.

The wealth and influence of the abbey extended to many daughter foundations, including St. Michael's Mount in Cornwall. However, its popularity and prestige as a centre of pilgrimage waned with the Reformation, and by the time of the French Revolution there were scarcely any monks in residence. The abbey was closed and converted into a prison, initially to hold clerical opponents of the republican regime. High-profile political prisoners followed, but by 1836, influential figures — including Victor Hugo — had launched a campaign to restore what was seen as a national architectural treasure. The prison was finally closed in 1863, and the mount was declared a historic monument in 1874. Mont Saint-Michel and its bay were added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in 1979, and it was listed with criteria such as cultural, historical, and architectural significance, as well as human-created and natural beauty.[7]

Abbey design

In the 11th century, William of Volpiano, the Italian architect who had built Fécamp Abbey in Normandy, was chosen by Richard II, Duke of Normandy, to be the building contractor. He designed the Romanesque church of the abbey, daringly placing the transept crossing at the top of the mount. Many underground crypts and chapels had to be built to compensate for this weight; these formed the basis for the supportive upward structure that can be seen today. Today Mont Saint-Michel is seen as a building of Romanesque architecture.

Robert de Thorigny, a great supporter of Henry II of England (who was also Duke of Normandy), reinforced the structure of the buildings and built the main façade of the church in the 12th century. In 1204, Guy of Thouars, regent for the Duchess of Brittany, as vassal of the King of France, undertook a siege of the Mount. After having set fire to the village and having massacred the population, he was obliged to beat a retreat under the powerful walls of the abbey. Unfortunately, the fire which he himself lit extended to the buildings, and the roofs fell prey to the flames. Horrified by the cruelty and the exactions of his Breton ally, Philip Augustus offered Abbot Jordan a grant for the construction of a new Gothic architectural set which included the addition of the refectory and cloister.[16]

Charles VI is credited with adding major fortifications to the abbey-mount, building towers, successive courtyards, and strengthening the ramparts.

Development

- 10th century

- 11th to 12th century

- 17th to 18th century

- 19th to 21st century

Administration

The islet belongs to the French commune of Le Mont-Saint-Michel, in the département of Manche, in Normandy. Population (1999): 46. The nearest major town, with an SNCF train station, is Pontorson. Le Mont-Saint-Michel belongs to the Organization of World Heritage Cities.

Mont Saint-Michel has also been the subject of traditional jealousy from the Bretons. Bretons claim that since the Couesnon River marks the traditional boundary between Normandy and Brittany, it is only because the river has altered its course over the centuries that the mount is on the Norman side of the border. This legend amuses the area's inhabitants, who state that the border is not located on the Couesnon River itself but on the mainland, 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) to the west, at the foot of the solid mass of Saint-Brelade.

Population

| Historical population of Le Mont-Saint-Michel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| From the year 1962 on: No double counting—residents of multiple communes (e.g. students and military personnel) are counted only once.

Since 2004, as for any city with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, censuses are every five years, in years ending in 1 and 6 for this city,[17] other counts are from annual population surveys. Source: EHESS[18] and Insee[19] · [20] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1956–1962 | 1962–1968 | 1968–1975 | 1975–1982 | 1982–1990 | 1990–1999 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| xx | 13 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 4 |

| 1956–1962 | 1962–1968 | 1968–1975 | 1975–1982 | 1982–1990 | 1990–1999 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| xx | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

Up to 20,000 people visit the city during the summer months. Among the 43 inhabitants as of 2006, 5 were monks and 7 nuns.

The Monastic Fraternities of Jerusalem

Since 24 June 2001, following the appeal addressed to them in 2000 by Bishop Jacques Fihey, Bishop of Coutances and Avranches[21], a community of monks and nuns of the Monastic Fraternities of Jerusalem, sent from the mother-house of St-Gervais-et-St-Protais in Paris, have been living as a community on Mont Saint-Michel. They replaced the Benedictine monks who returned to the Mount in 1966. They are tenants of the centre for national monuments and are not involved in the management of the abbey.

The community has seven sisters and four brothers. They live the mission that the Church has entrusted to them in their own charism of being "in the heart of the world" to be "in the heart of God". Their life revolves around prayer, work and fraternal life.[22] The community meets four times a day to recite the liturgical office in the abbey itself (or in the crypt of Notre-Dame des Trente Cierges in winter). In this way, the building keeps its original purpose as a place of prayer and singing the glory of God. The presence of the community attracts many visitors and pilgrims who come to join in the various liturgical celebrations.

In 2012, the community undertook the renovation of a house on the Mount, the Logis Saint-Abraham, which is used as a guest house for pilgrims on retreat.

People and places of note

- Robert of Torigni, famous abbot of the Mount;

- Guillaume de Saint Pair, monk of the abbey and author of the novel Mont Saint-Michel;

- The Duke of Chartres (later Louis-Philippe I) came to demolish the "iron cage";

- Mathurin Bruneau, shoemaker, rogue, and fake Louis XVII, prisoner in 1821-1822;

- Louis Auguste Blanqui, political prisoner in the Mount;

- Armand Barbès, political prisoner in the Mount;

- Monsignor Bravard, restorer of the abbey;

- La Mère Poulard, famous omelet restaurant;

- Émile Couillard, writer, historian of the Mount, and abbot of the Mont-Saint-Michel abbey.

Economy

Le Mont-Saint-Michel has long "belonged" to some families who shared the businesses in the town, and succeeded to the village administration. Tourism is the main and even almost unique source of income of the commune. There are about fifty shops for 3 million tourists, while only 25 people sleep every night on the Mount (monks included), except in hotels. Nowadays, the main institutions of the city are shared by:

- Eric Vannier, owner of the group the Mère Poulard (holding half of restaurants, shops, hotels and three museums);

- Jean-Yves Vételé, CEO of Sodetour (five hotels, a supermarket and shops -all extramural-, including Mercury Barracks);

- Patrick Gaul, former elected official, hotelier and intramural restaurateur;

- Independent merchants

Twin towns and sister cities

- Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima, Japan, where Itsukushima Shrine—another island-temple and UNESCO World Heritage Site—is located.[23][24][25]

Historically, Mont Saint-Michel was the Norman counterpart of St Michael's Mount in Cornwall, UK, which was given to the Benedictines, religious order of Mont-Saint-Michel, by Edward the Confessor in the 11th century. The two mounts share the same tidal island characteristics and the same conical shape, though St Michael's Mount is much smaller.[26]

In popular culture

- In 1904, the American intellectual Henry Adams privately published Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres[27] celebrating the unity of medieval society, especially as represented in the great cathedrals of France.

- French composer Claude Debussy frequented the island and possibly drew inspiration from not only the legend of the mythical city of Ys, but also Mont Saint-Michel's cathedral for his piano prelude La Cathédrale Engloutie.[28]

- 1991: Mindwalk[29]

- 1995: the island is the capital of the reign of Benoic in the Bernard Cornwell's novel The Winter King. The site is called Ynys Trebes at the time of the story.[30]

- 2003: Mont Saint-Michel was the inspiration for the design of Minas Tirith in the film The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King.[31]

- 2010: Mont Saint-Michel served as the artistic inspiration for the Disney hit Tangled. The castle and surrounding town are easily recognizable.[32]

- 2011: The design of Dark Souls location New Londo Ruins is inspired by Mont Saint-Michel.[33]

- 2012: The film To the Wonder features Mont-Saint-Michel as the primary image of the film. The protagonist and his lover are featured in the rose garden as the Prelude to Wagner's Parsifal plays. The lovers are shown along the beach, as the liminal space of the monastery and the sea acts as a symbol of their love.

See also

References

- ↑ With two hyphens and the French article "Le" ahead, because it is the name of a commune, not a hill.

- ↑ By far, the most famous part of the commune, known as the "Mont Saint-Michel" or the "Mount Saint-Michel", with only one hyphen and the name "Mont" untied, because it precisely means the hill, a geologic element, in this case an island.

- ↑ Institut géographique national (IGN) (ed.). "Commune of Le Mont-Saint-Michel's territory (scale 1:34110), the two mainland zones (enclaves) are visible, surrounded by a yellow line : one on the west of the Couesnon River is a relatively big one (387 ha), the other one on the east of the Couesnon River is a tiny one (6 ha)". geoportail.gouv.fr. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ "Communal limits : the three areas (two of them are on the mainland and the third one is the island itself) are each surrounded by an orange line". openstreetmap.org. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ "Insee – Populations légales 2009 – 50353-Le Mont-Saint-Michel". insee.fr. 2012. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "Mont Saint-Michel". xenophongroup.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- 1 2 "UNESCO". UNESCO. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ French government website Archived 12 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. (in French)

- ↑ L'Homer, A.; et al. (1999). Notice explicative, Carte géologique de la France (1/50 000), feuille Baie du mont-Saint-Michel (208) (PDF) (in French). Orléans: BRGM. ISBN 2-7159-1208-0. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2015.

- ↑ "Carnets géologique de Philippe Glangeaud - Glossaire" (in French). Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ Chantal Bonnot-Courtois, La Baie du Mont-Saint-Michel et l'estuaire de la Rance: environnements sédimentaires, aménagements et évolution récente. Editor Technip. 2002. pages 15–20

- ↑ "Official website of the restoring operation of the Mont Saint-Michel's maritime character". www.projetmontsaintmichel.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ "Mont Saint-Michel reclaims its island status". rfi.

- ↑ Galimberti, Katy (31 March 2015). "PHOTOS: Supertide Turns Mont Saint-Michel Into Island in a Once in 18-Year Spectacle". AccuWeather. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia: Mont-St-Michel". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1911. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Adams, Henry (1913). Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres: A Study of Thirteenth-Century Unity. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 37–38.

- ↑ "Département de la Manche". Insee.fr. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- ↑ "Le Mont-Saint-Michel - Notice Communale". Cassini.ehess.fr. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "Historique des populations par commune depuis le recensement de 1962". Insee.fr. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "Insee - Populations légales 2006 - 50353-Le Mont-Saint-Michel". Insee.fr. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ "Mont Saint Michel facts". Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Mont Saint Michel facts". Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ↑ "Le Mont-Saint-Michel – Jumelage" (in French). Wikimanche.fr. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Nishihiroshima Times". L-co.co.jp. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ "Miyajima Grand Hotel Info". Miyajima-arimoto.co.jp. 16 May 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- ↑ Henderson, Charles (1925). Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Oscar Blackford. pp. 160–61.

- ↑ Adams, Henry (1904). Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres. self-published. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016.

- ↑ Debussy's: La Cathedrale Engloutie

- ↑ "Mindwalk (Philosophical Films)". University of Tennessee at Martin. Philfilms.utm.edu. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ↑ Cornwell, Bernard (2015). The Winter King. Brazil: Record. pp. 273–314. ISBN 9788501061140.

- ↑ "Making Of" featurette on The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Extended Edition DVD.

- ↑ "10 Real Life Locations That Inspired Disney Films". Buzzfeed. buzzfeed.com. 20 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017.

- ↑ "Translation of the Design Works Interview with Hidetaka Miyazaki". Giant Bomb. giantbomb.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mont-Saint-Michel. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mont-Saint-Michel. |

- Mont-Saint-Michel Celebrates 1,300 yrs of History

- Mont Saint-Michel between history and legends

- Official Mont-Saint-Michel Tourist site (English version)

- Virtual recreation of Mont St. Michel in Second Life

- Pano at 360° of Mont St Michel

- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Mont Saint-Michel | Art Atlas

- INSEE population figures

.svg.png)