Ivermectin

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Stromectol, Soolantra cream |

| AHFS/Drugs.com |

Monograph (antiparasitic) FDA Professional Drug Information (rosacea) |

| MedlinePlus | a607069 |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | by mouth, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 93% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP450) |

| Elimination half-life | 18 hours |

| Excretion | Feces; <1% urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.067.738 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

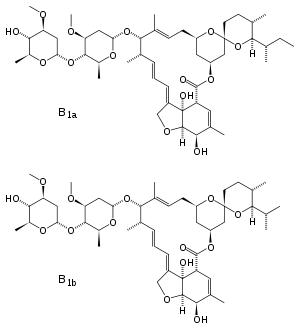

| Formula |

C 48H 74O 14 (22,23-dihydroavermectin B1a) C 47H 72O 14 (22,23-dihydroavermectin B1b) |

| Molar mass | 875.10 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Ivermectin is a medication that is effective against many types of parasites.[1] It is used to treat head lice,[2] scabies,[3] river blindness,[4] strongyloidiasis,[5] and lymphatic filariasis, among others.[6] It can be either applied to the skin or taken by mouth.[2] The eyes should be avoided.[2]

Common side effects include red eyes, dry skin, and burning skin.[2] It is unclear if it is safe for use during pregnancy, but is likely acceptable for use during breastfeeding.[7] It is in the avermectin family of medications and works by causing an increase in permeability of cell membrane resulting in paralysis and death of the parasite.[2]

Ivermectin was discovered in 1975 and came into medical use in 1981.[6][8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[9] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.12 for a course of treatment.[10] In the United States it costs $25–50 for a 50ml bottle suitable for about 25 doses.[11][5] In other animals it is used to prevent and treat heartworm among other diseases.[1]

Medical uses

Ivermectin is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic agent, traditionally against parasitic worms and other multicellular parasites. It is mainly used in humans in the treatment of onchocerciasis (river blindness), but is also effective against other worm infestations (such as strongyloidiasis, ascariasis, trichuriasis, filariasis and enterobiasis), and some epidermal parasitic skin diseases, including scabies.

Ivermectin is currently being used to help eliminate river blindness (onchocerciasis) in the Americas, and to stop transmission of lymphatic filariasis and onchocerciasis around the world in programs sponsored by the Carter Center using ivermectin donated by Merck.[12][13][14] The disease is common in 30 African countries, six Latin American countries, and Yemen.[15] The drug rapidly kills microfilariae, but not the adult worms. A single oral dose of ivermectin, taken annually for the 10–15-year lifespan of the adult worms, is all that is needed to protect the individual from onchocerciasis.[16]

Arthropod

More recent evidence supports its use against parasitic arthropods and insects:

- Mites such as scabies:[17][18][19] It is usually limited to cases that prove to be resistant to topical treatments or that present in an advanced state (such as Norwegian scabies).[19]

- Lice:[20][21] Ivermectin lotion (0.5%) is FDA-approved for patients six months of age and older.[22] After a single, 10-minute application of this formulation on dry hair, 78% of subjects were found to be free of lice after two weeks.[23] This level of effectiveness is equivalent to other pediculicide treatments requiring two applications.[24]

- Bed bugs:[25] Early research shows that the drug kills bed bugs when taken by humans at normal doses. The drug enters the human bloodstream and if the bedbugs bite during that time, they will die in a few days.

Rosacea

An ivermectin cream has been approved by the FDA, as well as in Europe, for the treatment of inflammatory lesions of rosacea. The treatment is based upon the hypothesis that parasitic mites of the genus Demodex play a role in rosacea. In a clinical study, ivermectin reduced lesions by 83% over 4 months, as compared to 74% under a metronidazole standard therapy.[26][27][28]

Contraindications

Ivermectin is contraindicated in children under the age of five, or those who weigh less than 15 kilograms (33 pounds)[29] and those who are breastfeeding, and have a liver or kidney disease.[30]

Side effects

The main concern is neurotoxicity, which in most mammalian species may manifest as central nervous system depression, and consequent ataxia, as might be expected from potentiation of inhibitory GABA-ergic synapses.

Dogs with defects in the P-glycoprotein gene (MDR1), often collie-like herding dogs, can be severely poisoned by ivermectin.

Since drugs that inhibit CYP3A4 enzymes often also inhibit P-glycoprotein transport, the risk of increased absorption past the blood-brain barrier exists when ivermectin is administered along with other CYP3A4 inhibitors. These drugs include statins, HIV protease inhibitors, many calcium channel blockers, and glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone, lidocaine, and the benzodiazepines.[31]

For dogs, the insecticide spinosad may have the effect of increasing the potency of ivermectin.[32]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Ivermectin and other avermectins (insecticides most frequently used in home-use ant baits) are macrocyclic lactones derived from the bacterium Streptomyces avermitilis. Ivermectin kills by interfering with nervous system and muscle function, in particular by enhancing inhibitory neurotransmission.

The drug binds to glutamate-gated chloride channels (GluCls) in the membranes of invertebrate nerve and muscle cells, causing increased permeability to chloride ions, resulting in cellular hyper-polarization, followed by paralysis and death.[2][33] GluCls are invertebrate-specific members of the Cys-loop family of ligand-gated ion channels present in neurons and myocytes.

Pharmacokinetics

Ivermectin can be given by mouth, topically, or via injection. It does not readily cross the blood–brain barrier of mammals due to the presence of P-glycoprotein,[34] (the MDR1 gene mutation affects function of this protein). Crossing may still become significant if ivermectin is given at high doses (in which case, brain levels peak 2–5 hours after administration). In contrast to mammals, ivermectin can cross the blood–brain barrier in tortoises, often with fatal consequences.

Ecotoxicity

Field studies have demonstrated the dung of animals treated with ivermectin supports a significantly reduced diversity of invertebrates, and the dung persists longer.[35]

History

The discovery of the avermectin family of compounds, from which ivermectin is chemically derived, was made by Satoshi Ōmura of Kitasato University, Tokyo and William C. Campbell of the Merck Institute for Therapeutic research. Ōmura identified avermectin from the bacterium Streptomyces avermitilis. Campbell purified avermectin from cultures obtained from Ōmura and led efforts leading to the discovery of ivermectin, a derivative of greater potency and lower toxicity.[36] Ivermectin was introduced in 1981.[37] Half of the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to Campbell and Ōmura for discovering avermectin, "the derivatives of which have radically lowered the incidence of river blindness and lymphatic filariasis, as well as showing efficacy against an expanding number of other parasitic diseases".[38]

Brand names

Ivermectin is available as a generic prescription drug in the U.S. in a 3 mg tablet formulation.[39] It is also sold under the brand names Heartgard, Sklice[40] and Stromectol[41] in the United States, Ivomec worldwide by Merial Animal Health, Mectizan in Canada by Merck, Iver-DT[42] in Nepal by Alive Pharmaceutical and Ivexterm in Mexico by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International. In Southeast Asian countries, it is marketed by Delta Pharma Ltd. under the trade name Scabo 6. The formulation for rosacea treatment is sold as Soolantra. While in development, it was assigned the code MK-933 by Merck.[43]

Veterinary use

In veterinary medicine ivermectin is used against many intestinal worms (but not tapeworms), most mites, and some lice. It is not effective for eliminating ticks, flies, flukes, or fleas. Eggs and larvae mature and come back to the host. It is effective against larval heartworms, but not against adult heartworms, though it may shorten their lives. The dose of the medicine must be very accurately measured as it is very toxic in over-dosage. It is sometimes administered in combination with other medications to treat a broad spectrum of animal parasites. Some dog breeds (especially the Rough Collie, the Smooth Collie, the Shetland Sheepdog, and the Australian Shepherd), though, have a high incidence of a certain mutation within the MDR1 gene (coding for P-glycoprotein); affected animals are particularly sensitive to the toxic effects of ivermectin.[44][45] Clinical evidence suggests kittens are susceptible to ivermectin toxicity.[46] A 0.01% ivermectin topical preparation for treating ear mites in cats (Acarexx) is available.

Ivermectin is sometimes used as an acaricide in reptiles, both by injection and as a diluted spray. While this works well in some cases, care must be taken, as several species of reptiles are very sensitive to ivermectin. Use in turtles is particularly contraindicated.

Research

Ivermectin is also being studied as a potential antiviral agent against the viruses chikungunya and yellow fever.[47]

A 2012 Cochrane review found weak evidence suggesting that ivermectin could result in the reduction of chorioretinal lesions and prevent loss of vision in people with onchocerciasis.[48]

In 2013, this antiparasitic drug was demonstrated as a novel ligand of farnesoid X receptor (FXR),[49][50] a therapeutic target for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease.[51]

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs: Small and Large Animal (4 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2015. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-323-24486-2. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Ivermectin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on January 3, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ↑ Panahi, Y; Poursaleh, Z; Goldust, M (2015). "The efficacy of topical and oral ivermectin in the treatment of human scabies". Annals of Parasitology. 61 (1): 11–6. PMID 25911032.

- ↑ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery a History. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Richard J. (2014). Tarascon pocket pharmacopoeia : 2014 deluxe lab-pocket edition (15th ed.). Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 422. ISBN 978-1-284-05399-9. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016.

- 1 2 Mehlhorn, Heinz (2008). Encyclopedia of parasitology (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 646. ISBN 978-3-540-48994-8. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016.

- ↑ "Ivermectin Levels and Effects while Breastfeeding". Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ↑ Vercruysse, edited by J.; Rew, R.S. (2002). Macrocyclic lactones in antiparasitic therapy. Oxon, UK: CABI Pub. p. Preface. ISBN 978-0-85199-840-4. Archived from the original on January 31, 2016.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 13, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Ivermectin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Ivomec Injection 1% 50ml Btl".

- ↑ The Carter Center. "River Blindness (Onchocerciasis) Program". Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- ↑ The Carter Center. "Lymphatic Filariasis Elimination Program". Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2008.

- ↑ WHO. "African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control". Archived from the original on September 22, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ↑ United Front Against Riverblindness. "Onchocerciasis or Riverblindness". Archived from the original on August 26, 2007.

- ↑ United Front Against Riverblindness. "Control of Riverblindness". Archived from the original on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ Brooks PA, Grace RF (August 2002). "Ivermectin is better than benzyl benzoate for childhood scabies in developing countries". J Paediatr Child Health. 38 (4): 401–4. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00015.x. PMID 12174005.

- ↑ Victoria J, Trujillo R (2001). "Topical ivermectin: a new successful treatment for scabies". Pediatr Dermatol. 18 (1): 63–5. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018001063.x. PMID 11207977.

- 1 2 Strong M, Johnstone PW (2007). Strong, Mark, ed. "Interventions for treating scabies". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD000320. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000320.pub2. PMID 17636630.

- ↑ Dourmishev AL; Dourmishev LA; Schwartz RA (December 2005). "Ivermectin: pharmacology and application in dermatology". International Journal of Dermatology. 44 (12): 981–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02253.x. PMID 16409259.

- ↑ Strycharz JP; Yoon KS; Clark JM (January 2008). "A new ivermectin formulation topically kills permethrin-resistant human head lice (Anoplura: Pediculidae)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 45 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[75:ANIFTK]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-2585. PMID 18283945.

- ↑ "Sklice lotion" Archived May 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ David M. Pariser, M.D.; Terri Lynn Meinking, Ph.D.; Margie Bell, M.S.; William G. Ryan, B.V.Sc. (November 1, 2012). "Topical 0.5% Ivermectin Lotion for Treatment of Head Lice". New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (18): 1687–1693. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1200107. PMID 23113480.

- ↑ Study shows ivermectin ending lice problem in one treatment, Los Angeles Times, November 5, 2012

- ↑ DONALD G. MCNEIL JR. (December 31, 2012). "Pill Could Join Arsenal Against Bedbugs". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Galderma Receives FDA Approval of Soolantra (Ivermectin) Cream for Rosacea Archived January 22, 2015, at the Wayback Machine."

- ↑ "SOOLANTRA- ivermectin cream (NDC Code(s): 0299-3823-30, 0299-3823-45, 0299-3823-60)". DailyMed. December 2014. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Galderma Announces Positive Outcome of European Decentralised Procedure for Approval of Soolantra (ivermectin) Cream 10mg/g for Rosacea Patients". Galderma. March 27, 2015. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ↑ Dourmishev AL; Dourmishev LA; Schwartz RA (December 2005). "Ivermectin: pharmacology and application in dermatology". International Journal of Dermatology. 44 (12): 981–988. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02253.x. PMID 16409259.

- ↑ Heukelbach, J; Winter, B; Wilcke, T; Muehlen, M; Albrecht, S; de Oliveira, FA; Kerr-Pontes, LR; Liesenfeld, O; Feldmeier, H (August 2004). "Selective mass treatment with ivermectin to control intestinal helminthiases and parasitic skin diseases in a severely affected population". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82 (8): 563–71. PMC 2622929. PMID 15375445.

- ↑ Goodman and Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 11th edition, pages 122, 1084–1087.

- ↑ "COMFORTIS® and ivermectin interaction Safety Warning Notification". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Archived from the original on August 29, 2009.

- ↑ Yates DM, Wolstenholme AJ (August 2004). "An ivermectin-sensitive glutamate-gated chloride channel subunit from Dirofilaria immitis". Int. J. Parasitol. 34 (9): 1075–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.04.010. PMID 15313134.

- ↑ Borst P, Schinkel AH (June 1996). "What have we learnt thus far from mice with disrupted P-glycoprotein genes?". European Journal of Cancer. 32 (6): 985–990. doi:10.1016/0959-8049(96)00063-9.

- ↑ Iglesias LE, Saumell CA, Fernández AS, et al. (December 2006). "Environmental impact of ivermectin excreted by cattle treated in autumn on dung fauna and degradation of faeces on pasture". Parasitology Research. 100 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1007/s00436-006-0240-x. PMID 16821034.

- ↑ Fisher MH, Mrozik H (1992). "The chemistry and pharmacology of avermectins". Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 32: 537–53. doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.002541. PMID 1605577.

- ↑ W. C. CAMPBELL; R. W. BURG; M. H. FISHER; R. A. DYBAS (June 26, 1984). "1". Pesticide Synthesis Through Rational Approaches. ACS Symposium Series. 255. American Chemical Society. pp. 5–20. doi:10.1021/bk-1984-0255.ch001. ISBN 978-0-8412-1083-7.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2015" (PDF). Nobel Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ↑ U.S. FDA. "Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA): 204154". Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ "SKLICE- ivermectin lotion (NDC Code(s): 49281-183-71)". DailyMed. February 2012. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ↑ "STROMECTOL- ivermectin tablet (NDC Code(s): 0006-0032-20)". DailyMed. May 2010. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- ↑ Adhikari, Santosh (May 27, 2014). "ALIVE PHARMACEUTICAL (P) LTD.: Iver-DT". ALIVE PHARMACEUTICAL (P) LTD. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ↑ Pampiglione S; Majori G; Petrangeli G; Romi R (1985). "Avermectins, MK-933 and MK-936, for mosquito control". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 79 (6): 797–9. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(85)90121-X. PMID 3832491.

- ↑ "MDR1 FAQs" Archived December 13, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Australian Shepherd Health & Genetics Institute, Inc.

- ↑ "Multidrug Sensitivity in Dogs" Archived June 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., Washington State University's College of Veterinary Medicine

- ↑ Frischke H, Hunt L (April 1991). "Suspected ivermectin toxicity". Canadian Veterinary Journal. 32 (4): 245. PMC 1481314. PMID 17423775.

- ↑ Varghese FS; et al. (Feb 2016). "Discovery of berberine, abamectin and ivermectin as antivirals against chikungunya and other alphaviruses". Antiviral Res. 126: 117–24. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.12.012. PMID 26752081.

- ↑ Ejere HO, Schwartz E, Wormald R, Evans JR (2012). "Ivermectin for onchocercal eye disease (river blindness)". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 8 (8): CD002219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002219.pub2. PMC 4425412. PMID 22895928.

- ↑ Carotti A, Marinozzi M, Custodi C, Cerra B, Pellicciari R, Gioiello A, Macchiarulo A (2014). "Beyond bile acids: targeting Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) with natural and synthetic ligands". Curr Top Med Chem. 14 (19): 2129–42. doi:10.2174/1568026614666141112094058. PMID 25388537.

- ↑ Jin, L; Feng, X; Rong, H; Pan, Z; Inaba, Y; Qiu, L; Zheng, W; Lin, S; Wang, R; Wang, Z; Wang, S; Liu, H; Li, S; Xie, W; Li, Y (2013). "The antiparasitic drug ivermectin is a novel FXR ligand that regulates metabolism". Nature Communications. 4: 1937. doi:10.1038/ncomms2924. PMID 23728580.

- ↑ Kim, Sun-Gi; Kim, Byung-Kwon; Kim, Kyumin; Fang, Sungsoon (17 May 2017). "Bile Acid Nuclear Receptor Farnesoid X Receptor: Therapeutic Target for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease". Endocrinology and Metabolism. 31 (4): 500–504. doi:10.3803/EnM.2016.31.4.500. ISSN 2093-596X. PMC 5195824. PMID 28029021.

External links

- Stromectol

- The Carter Center River Blindness (Onchocerciasis) Control Program

- Mectizan Donation Program

- American NGDO Treating River Blindness

- MERCK. 25 Years: The MECTIZAN® Donation ProgramArchived October 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- Trinity College Dublin. Prof William Campbell – The Story of Ivermectin

- "IVERMECTIN- ivermectin tablet (NDC Code(s): 42799-806-01)". DailyMed. November 2014. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- "ivermectin (Rx) Stromectol". Medscape. WebMD. Retrieved November 1, 2015.