Fenethylline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.115.827 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

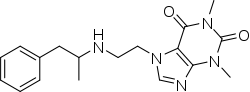

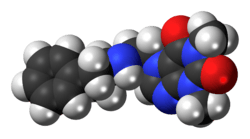

| Formula | C18H23N5O2 |

| Molar mass | 341.408 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Fenethylline (BAN, USAN) is a codrug of amphetamine and theophylline which behaves as a prodrug to both of the aforementioned drugs. It is also spelled phenethylline and fenetylline (INN); other names for it are amphetamin

History

Fenethylline was first synthesized by the German Degussa AG in 1961 and used for around 25 years as a milder alternative to amphetamine and related compounds.[3] Although there are no FDA-approved indications for fenethylline, it was used in the treatment of "hyperkinetic children" (what would now be referred to as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) and, less commonly, for narcolepsy and depression. One of the main advantages of fenethylline was that it does not increase blood pressure to the same extent as an equivalent dose of amphetamine and so could be used in patients with cardiovascular conditions.[4]

Fenethylline was considered to have fewer side effects and less potential for abuse than amphetamine. Nevertheless, fenethylline was listed in 1981 as a schedule I controlled substance in the US, and it became illegal in most countries in 1986 after being listed by the World Health Organization for international scheduling under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, even though the actual incidence of fenethylline abuse was quite low.[4]

Pharmacology

The fenetylline molecule results when theophylline is covalently linked with amphetamine via an alkyl chain.[5]

Fenethylline is metabolized by the body to form two drugs, amphetamine (24.5% of oral dose) and theophylline (13.7% of oral dose), both of which are active stimulants. The physiological effects of fenethylline therefore seem to result from a combination of these two compounds,[6][7] although this is not entirely clear.[4]

Abuse and illegal trade

Abuse of fenethylline of the brand name Captagon is most common in Arab countries and counterfeit versions of the drug continue to be available despite its illegality.[8][9] In 2017 captagon was the most popular narcotic in the Arabian peninsula.[10]

Many of these counterfeit "Captagon" tablets actually contain other amphetamine derivatives that are easier to produce, but are pressed and stamped to look like Captagon pills. Some counterfeit Captagon pills analysed do contain fenethylline however, indicating that illicit production of this drug continues to take place .

Fenethylline is a popular drug in Western Asia, and is allegedly used by militant groups in Syria.[11] It is manufactured locally in a cheap and simple process and it sells for between $5 and $20 per pill.[12] According to some leaks, militant groups also export the drug in exchange for weapons and cash.[13][14] According to Abdelelah Mohammed Al-Sharif, secretary general of the National Committee for Narcotics Control and assistant director of Anti-Drug and Preventative Affairs, 40% of the drug users who fall in the 12–22 age group in Saudi Arabia are addicted to fenethylline.[15]

On 26 October 2015, a member of the Saudi royal family, Prince Abdel Mohsen Bin Walid Bin Abdulaziz, and four others were detained in Beirut on charges of drug trafficking after airport security discovered two tons of Captagon (fenethylline) pills and some cocaine on a private jet scheduled to depart for the Saudi capital of Riyadh.[16][17][18] The following month, Agence France Press reported that the Turkish authorities had seized 2 tonnes of Captagon during raids in the Hatay region on the Syrian border. The pills, almost 11 million of them, had been produced in Syria and were being shipped to countries in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf.[19]

On 31 December 2015 the Lebanese Army announced that it had discovered two large scale drug production workshops in the north of the country. Large quantities of Captagon pills were seized. Two days earlier three tons of Captagon and hashish were seized at Beirut airport. The drugs were concealed in school desks being exported to Egypt.[20]

The drug is playing a role in the Syrian civil war.[21][22] The production and sale of fenethylline generates large revenues which are likely used to fund weapons, as well as combatants on different sides using the stimulant to keep them fighting.[22][23][24]

References to the drug were found on a mobile phone used by Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, a French-Tunisian who killed 84 civilians in Nice on Bastille Day, 2016.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ Dictionary of Organic Compounds. CRC Press. pp. 3140–. ISBN 978-0-412-54090-5.

- ↑ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 431–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ↑ Kristen, G; Schaefer, A; von Schlichtegroll, A (1986). "Fenetylline: Therapeutic use, misuse and/or abuse". Drug and alcohol dependence. 17 (2–3): 259–71. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(86)90012-8. PMID 3743408.

- 1 2 3 Maria Katselou (2016). "Fenethylline (Captagon) Abuse – Local Problems from an Old Drug Become Universal". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 119 (2): 133–140. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12584.

- ↑ Bernd Nickel; et al. (1986). "Fenetylline: New results on pharmacology, metabolism and kinetics". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 17 (2–3): 235–257. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(86)90011-6.

- ↑ Theodore Ellison et al. (1970): The metabolic fate of 3H-fenethylline in man. In: European Journal of Pharmacology. 13, p. 123. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(70)90192-5

- ↑ Alabdalla, M. A. (2005). "Chemical characterization of counterfeit captagon tablets seized in Jordan". Forensic Science International. 152 (2–3): 185–8. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.08.004. PMID 15978343.

- ↑ "2011 Global Assessment of Amphetamine-Type Stimulants" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- ↑ "Le Captagon®, arme principale des jihadistes". Reseau Voltaire.

- ↑ "A new drug of choice in the Gulf". The Economist. 18 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Todd, Brian; McConnell, Dugald (21 November 2015). "Syria fighters may be fueled by amphetamines". CNN. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ Holley, Peter (19 November 2015). "The tiny pill fueling Syria's war and turning fighters into superhuman soldiers". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Colin Freeman (12 January 2014). "Syria's civil war being fought with fighters high on drugs". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Stephen Kalin (12 January 2014). "Insight: War turns Syria into major amphetamines producer, consumer". Reuters. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ "'40% of young Saudi drug addicts taking Captagon'". Arab News. Jeddah. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Spencer, Richard (26 October 2015). "Saudi prince held after seizure of two tonnes of amphetamines at Beirut airport". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Baker, Graeme (26 October 2015). "Saudi prince arrested in Lebanon trying to smuggle two tonnes of amphetamine pills out of the country by private jet". The Independent. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Vinograd, Cassandra; Kassem, Mustafa (26 October 2015). "Saudi Royal, Four Others Detained in Beirut Captagon Bust". NBC News. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (20 November 2015). "Turkey seizes 11 million pills of 'Syria war drug': Reports". The Times of India. Istanbul. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ↑ The Daily Star (Lebanon): Tuesday raids in east Lebanon netted 800kg of hash:police and Lebanese Army busts two drug factories

- ↑ https://www.vox.com/world/2015/11/20/9769264/captagon-isis-drug

- 1 2 Henley, Jon (13 January 2014). "Captagon: the amphetamine fuelling Syria's civil war". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ↑ "Insight - War turns Syria into major amphetamines producer, consumer". Reuters UK. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Baker, Aryn. "Syria's Breaking Bad: Are Amphetamines Funding the War?". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ CNN, Ray Sanchez. "Attacker in Nice plotted for months with 'accomplices'". CNN. Retrieved 2016-07-21.