Demodex

| Demodex | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Trombidiformes |

| Family: | Demodicidae |

| Genus: | Demodex Owen, 1843[1] |

| Type species | |

| Acarus folliculorum Simon, 1842 | |

| Species | |

| |

Demodex is a genus of tiny mites that live in or near hair follicles of mammals.

Around 65 species of Demodex are known.[2] Two species live on humans: Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis, both frequently referred to as eyelash mites. Different species of animals host different species of Demodex. Demodex canis lives on the domestic dog. Infestation with Demodex is common and usually does not cause any symptoms, although occasionally some skin diseases can be caused by the mites. Demodex is derived from Greek δημός dēmos "fat" and δήξ dēx, "woodworm".[3]

D. folliculorum and D. brevis

D. folliculorum and D. brevis are typically found on humans. D. folliculorum was first described in 1842 by Simon; D. brevis was identified as separate in 1963 by Akbulatova. D. folliculorum is found in hair follicles, while D. brevis lives in sebaceous glands connected to hair follicles. Both species are primarily found in the face, near the nose, the eyelashes, and eyebrows, but also occur elsewhere on the body.

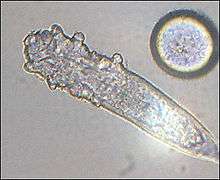

The adult mites are only 0.3–0.4 mm (0.012–0.016 in) long, with D. brevis slightly shorter than D. folliculorum.[4] Each has a semitransparent, elongated body that consists of two fused segments. Eight short, segmented legs are attached to the first body segment. The body is covered with scales for anchoring itself in the hair follicle, and the mite has pin-like mouthparts for eating skin cells and oils (sebum) which accumulate in the hair follicles. The mites can leave the hair follicles and slowly walk around on the skin, at a speed of 8–16 mm (0.31–0.63 in) per hour, especially at night, as they try to avoid light.[4] The mites are transferred between hosts through contact with hair, eyebrows, and the sebaceous glands of the face.

Females of D. folliculorum are larger and rounder than males. Both male and female Demodex mites have a genital opening, and fertilization is internal.[5] Mating takes place in the follicle opening, and eggs are laid inside the hair follicles or sebaceous glands. The six-legged larvae hatch after three to four days, and the larvae develop into adults in about seven days. The total lifespan of a Demodex mite is several weeks.

Health issues

Older people are much more likely to carry the mites; about a third of children and young adults, half of adults, and two-thirds of elderly people carried them.[6] The lower rate in children may be because children produce less sebum. Recently, a study of 29 adults (18 and over) in North Carolina, US, found that 70% of those 18 years of age carried mites, and that all adults over 18 (n = 19) carried them.[7] This study (using a DNA detection method, more sensitive than traditional sampling and observation by microscope), along with several studies of cadavers, suggests that previous work might have underestimated the mites' prevalence. However, the small sample size and small geographical area involved prevent drawing broad conclusions from these data.

Demodicosis

Demodex were considered commensals but are now considered parasitic. However, in the vast majority of cases the mites go unobserved without any adverse symptoms, though in certain cases (usually related to a suppressed immune system, caused by stress or illness), mite populations can dramatically increase. This results in a condition known as demodicosis or Demodex mite bite, characterised by itching, inflammation, and other skin disorders. Blepharitis (inflammation of the eyelids) can be also caused by Demodex mites.[8][9]

Research

Research about human infection by Demodex mites is ongoing:[10][11][12][13]

- Evidence of a correlation between Demodex infection and acne vulgaris exists, suggesting it might play a role in promoting acne.[12]

- Several preliminary studies suggesting an association between mite infection and rosacea.[14][15]

D. canis

The natural host of Demodex canis is the domestic dog. Although it can temporarily infect humans, D. canis mites cannot survive on the human skin and therefore will die shortly after exposure and are considered not to be zoonotic. Naturally, the D. canis mite has a commensal relationship with the dog and therefore under normal conditions does not produce any clinical signs or disease. The escalation of a commensal D. canis infestation into one requiring clinical attention usually involves complex immune factors. Under normal health conditions the mite can live within the dermis of the dog without causing any harm to the animal.

However, whenever an immunosuppressive condition is present and the dog's immune system (which normally ensures that the mite population cannot escalate to an infestation that can damage the dermis of the host) is compromised, it allows the mites to proliferate. As they continue to infest the host, clinical signs begin to become apparent and demodicosis/demodectic mange/red mange is diagnosed.

Demodicosis can manifest as lesions of two types: squamous, which causes dry alopecia and thickening of the skin, and pustular, which is the more severe form, causing secondary infection (usually by Staphylococcus), resulting in the characteristic numerous red pustules and wrinkling of the skin. Demodicosis can follow immunosuppressive conditions or treatments, or may be related to a genetic immune deficiency. Also, certain breeds—such as the Dalmatian, the American Bulldog, and the American Pit Bull Terrier—appear to be more susceptible.[16]

Since D. canis is a part of the natural fauna on a canine's skin, the mite is not considered to be contagious. All dogs receive an initial exposure from their mother during nursing. The immune system of the animal under most all healthy conditions keeps the population of the mite in check and therefore subsequent exposure to dogs possessing clinical demodectic mange does not increase an animal's chance of developing demodicosis. Since demodicosis is usually the result of an immune deficiency, it is not uncommon for subsequent infestations after treatment to occur.

References

- ↑ Owen, [Richard] (1843). "Lecture XIX. Arachnida". Lectures on Comparative Anatomy. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 252.

- ↑ Yong, Ed (August 31, 2012). "Everything you never wanted to know about the mites that eat, crawl, and have sex on your face". Not Exactly Rocket Science. Discover. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ "Demodex". Medical Dictionary (medicine.academic.ru).

- 1 2 Rufli, T.; Mumcuoglu, Y. (1981). "The hair follicle mites Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis: biology and medical importance. A review". Dermatologica. 162 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1159/000250228. PMID 6453029.

- ↑ Rush, Aisha (2000). "Demodex folliculorum". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ Sengbusch, H. G.; Hauswirth, J. W. (1986). "Prevalence of hair follicle mites, Demodex folliculorum and D. brevis (Acari: Demodicidae), in a selected human population in western New York, USA". Journal of Medical Entomology. 23 (4): 384–388. doi:10.1093/jmedent/23.4.384. PMID 3735343.

- ↑ Thoemmes, Megan S.; Fergus, Daniel J.; Urban, Julie; Trautwein, Michelle; Dunn, Robert R.; Kolokotronis, Sergios-Orestis (27 August 2014). "Ubiquity and Diversity of Human-Associated Demodex Mites". PLoS ONE. 9 (8): e106265. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106265. PMC 4146604. PMID 25162399.

- ↑ Marcinowska, Z; Kosik-Bogacka, D; Lanocha-Arendarczyk, N; Czepita, D; Lanocha, A (2015). "[Demodex folliculorum and demodex brevis]". Pomeranian journal of life sciences. 61 (1): 108–14. doi:10.21164/pomjlifesci.62. PMID 27116866.

- ↑ Lindsey, Kristina; Matsumara, Sueko; Hatel, Elham; Akpek, Esen K. (16 May 2012). "Interventions for chronic blepharitis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD00556. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005556.pub2. PMC 4270370. PMID 22592706.

- ↑ Liu, Jingbo; Sheha, Hosam; Tseng, Scheffer C. G. (October 2010). "Pathogenic role of Demodex mites in blepharitis". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 10 (5): 505–510. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833df9f4. PMC 2946818. PMID 20689407.

- ↑ Zhao, Ya-e; Peng, Yan; Wang, Xiang-lan; Wu, Li-ping; Wang, Mei; Yan, Hu-ling; Xiao, Sheng-xiang (December 2011). "Facial dermatosis associated with Demodex: a case-control study". Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B. 12 (8): 1008–1015. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1100179. PMC 3232434. PMID 22135150.

- 1 2 Zhao, Ya-e; Hu, Li; Wu, Li-ping; Ma, Jun-xian (March 2012). "A meta-analysis of association between acne vulgaris and Demodex infestation". Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B. 13 (3): 192–202. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1100285. PMC 3296070. PMID 22374611.

- ↑ "2011-2012 Annual Evidence Update on Acne vulgaris" (PDF). University of Nottingham Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology. 2012. p. 10. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- ↑ MacKenzie, Debora (August 30, 2012). "Rosacea may be caused by mite faeces in your pores". New Scientist. Retrieved August 30, 2012.

- ↑ Jarmuda, Stanisław; O'Reilly, Niamh; Żaba, Ryszard; Jakubowicz, Oliwia; Szkaradkiewicz, Andrzej; Kavanagh, Kevin (August 2012). "The potential role of Demodex folliculorum mites and bacteria in the induction of rosacea". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 61: 1504–10. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.048090-0. PMID 22933353.

- ↑ Urquhart, G. M. (1996). Veterinary Parasitology (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-632-04051-3.

16. Shipstone, Michael. "Antiparasitics for Integumentary Disease: Ivermectin," http://www.merckvetmanual.com/pharmacology/systemic-pharmacotherapeutics-of-the-integumentary-system/antiparasitics-for-integumentary-disease#v3331036

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Demodex. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Demodex |

- Demodex, an inhabitant of human hair follicles, and a mite which we live with in harmony, by M. Halit Umar, published in the May 2000 edition of Micscape Magazine, includes several micrographs

- Demodicosis, an article by Manolette R Roque, MD

- Demodetic Mange in Dogs, by T. J. Dunn, Jr. DVM