Grand Central Terminal

Grand Central Terminal  | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metro-North Railroad terminal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) The Main Concourse, 2015 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location |

89 East 42nd Street at Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°45′10.08″N 73°58′35.48″W / 40.7528000°N 73.9765222°WCoordinates: 40°45′10.08″N 73°58′35.48″W / 40.7528000°N 73.9765222°W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by |

Midtown TDR Ventures (leased to Metro-North Railroad) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line(s) | Park Avenue Main Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms |

44 high-level platforms (43 island platforms, 1 side platform) (6 tracks with Spanish solution) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 56 (30 on upper level, 26 on lower level), 43 in use for passenger service | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connections |

MTA New York City Subway: at Grand Central–42nd Street | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platform levels | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Disabled access | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | GCT, NYG[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fare zone | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website |

Official website | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1871 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1913, 1994–2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Grand Central Terminal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Grand Central Terminal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Built | 1903 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect |

Reed and Stem; Warren and Wetmore | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NRHP reference # |

75001206 83001726 (increase) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Significant dates | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Added to NRHP |

January 17, 1975 August 11, 1983 (increase)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated NHL | December 8, 1976[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Designated NYCL | August 2, 1967 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

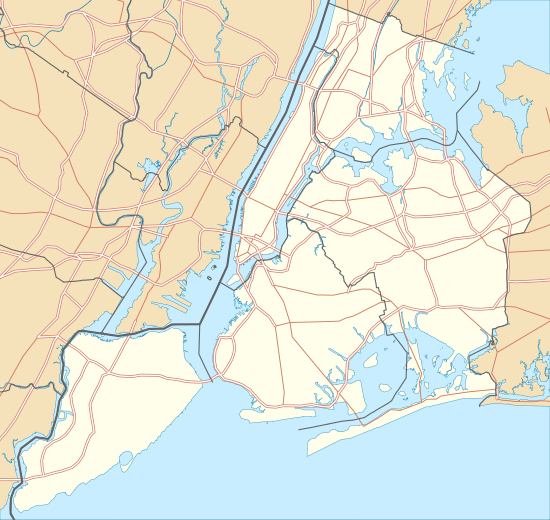

Grand Central Terminal Location within New York City  Grand Central Terminal Grand Central Terminal (New York)  Grand Central Terminal Grand Central Terminal (the US) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

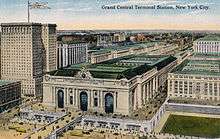

Grand Central Terminal (GCT; also referred to as Grand Central Station or simply as Grand Central) is a commuter railroad terminal at 42nd Street and Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City, United States. The terminal serves commuters traveling on the Metro-North Railroad to Westchester, Putnam, and Dutchess counties in New York, as well as to Fairfield and New Haven counties in Connecticut. The terminal also contains a connection to the New York City Subway at Grand Central–42nd Street.

Grand Central Terminal's distinctive architecture and interior design have earned it several landmark designations, including as a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The terminal is one of the world's most visited tourist attractions, with 21.9 million visitors in 2013, excluding train and subway passengers.

Grand Central Terminal was built by and named for the New York Central Railroad in the pinnacle of American long-distance passenger rail travel. Until 1991, the terminal also served Amtrak, which consolidated all of its services at nearby Pennsylvania Station upon completion of the Empire Connection. Limited Amtrak service also served the station during the summer of 2017, as well as all New York-bound Amtrak service not using the Northeast Corridor in summer 2018, because of construction around Penn Station. The East Side Access project, which will bring Long Island Rail Road service to the terminal, is expected to be completed in late 2022.

Grand Central covers 48 acres (19 ha) and has 44 platforms, more than any other railroad station in the world. Its platforms, all below ground, serve 30 tracks on the upper level and 26 on the lower, though only 43 tracks are currently in use for passenger service. The total number of tracks along platforms and in rail yards exceeds 100 as most previous tracks that are not in regular use are used for the rail yard. Unlike other Metro-North stations, Grand Central Terminal is not owned by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, but by a private company known as Midtown TDR Ventures.

Naming

Although the terminal has been officially called "Grand Central Terminal" since the present structure opened, it has "always been more colloquially and affectionately known as Grand Central Station", a name of one of the earlier railroad stations on the same site.[4][5][N 1] "Grand Central Station" is the name of the nearby U.S. Post Office station at 450 Lexington Avenue,[6] but may also refer to the Grand Central–42nd Street subway station that is located next to the terminal. The name was also used for the renovated Grand Central Depot, from 1900 until its demolition in 1903.

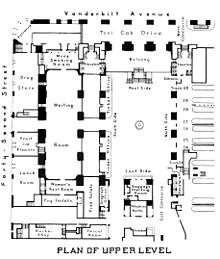

Layout

The tracks are numbered according to their location in the terminal building. The upper-level tracks are numbered 11 to 42 east to west. Tracks 22 and 31 were removed in the late 1990s to build concourses for Grand Central North. Track 12 was removed to expand the platform between tracks 11 and 13 and track 14 is only used for loading a garbage train. The lower level has 27 tracks, numbered 100 to 126, east to west; currently, only tracks 102–112, and 114–116 are used for passenger service. Odd-numbered tracks are usually on the east side (right side facing north) of the platform; even-numbered tracks on the west.

Grand Central Terminal has both monumental spaces and meticulously crafted detail, especially on its facade.[7] In a February 2013 BBC News article, historian David Cannadine described it as one of the most majestic buildings of the twentieth century.[8] In 2013, Grand Central Terminal hosted 21.6 million visitors, putting it among the ten most-visited tourist attractions in the world.[9]

Its interior has restaurants, such as the Oyster Bar, and various fast food outlets, including a Shake Shack,[10][11] surrounding the Dining Concourse on the level below the Main Concourse, as well as delis, bakeries, and a gourmet and fresh food market. There is an annex of the New York Transit Museum. The 40-plus retail stores include newsstands and chain stores, including a Starbucks coffee shop, a Rite Aid pharmacy and, since December 2011, an Apple Store.[12][13]

Grand Central Terminal's 49-acre (20 ha) basements are among the largest in the city.[14] This includes M42, a "secret" sub-basement under the terminal that contains the AC-to-DC converters used to supply DC traction current to the tracks. The exact location of M42 is a closely guarded secret and does not appear on maps, though it has been shown on the History Channel program Cities of the Underworld and a National Geographic special. Two of the original rotary converters were not removed in the late 20th century when solid-state ones took over their job, and they remain as a historical record. During World War II, this facility was closely guarded because its sabotage would have impaired troop movement on the Eastern Seaboard.[14][15][16] It is said that any unauthorized person entering the facility during the war risked being shot on sight; the rotary converters could have easily been crippled by a bucket of sand.[17] Abwehr (a German espionage service) sent two spies to sabotage it; they were arrested by the FBI before they could strike.[14]

The terminal building primarily uses granite, so the building emits radiation.[18] People who work full-time in the station receive an average dose of 525 mrem/year, more than permitted in nuclear power facilities.[19][20]

Midtown TDR Ventures has owned the station since 2006, when Argent Ventures transferred ownership of the station.[21] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the state agency that is the parent of Metro-North, holds a lease until 2274.[22]

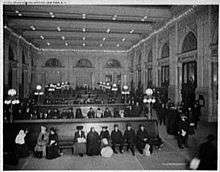

Main Concourse

The Main Concourse is the center of Grand Central. At 275 ft (84 m) long by 120 ft (37 m) wide by 125 ft (38 m) high,[23][24][25]:74 the cavernous Main Concourse is usually filled with bustling crowds. and is often used as a meeting place.[26] The ticket booths are here, although many now stand unused or have been repurposed since the introduction of ticket vending machines.[26] The large American flag was hung in Grand Central Terminal a few days after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. The main information booth is in the center of the concourse.[26] The four-faced brass clock on top of the information booth, perhaps the most recognizable icon of Grand Central, was designed by Henry Edward Bedford and cast in Waterbury, Connecticut.[26] Each of the four clock faces is made from opalescent glass (now often called opal glass or milk glass), though urban legend has it that the faces are made of opal and that Sotheby's and Christie's have estimated their value to be between $10 million and $20 million. A 1954 New York Times article[27] on the restoration of the clock notes that "Each of the glass faces was twenty-four inches in diameter...." Within the marble and brass pagoda lies a "secret" door that conceals a spiral staircase leading to the lower-level information booth.

Outside the station, the 13-foot (4.0 m) clock in front of the Grand Central façade facing 42nd Street contains the world's largest example of Tiffany glass. It is surrounded by the Glory of Commerce sculptural group, which includes representations of Minerva, Hercules, and Mercury. The sculptures were designed by French sculptor Jules-Felix Coutan and carved by the John Donnelly Company. At its unveiling in 1914, the 48-foot-high (15 m) trio was considered the largest sculptural group in the world.

The upper-level tracks are reached from the Main Concourse or from various hallways and passages branching off from it. On the east side of the Main Concourse is a cluster of food purveyor shops called Grand Central Market.

Display board

The original blackboard with arrival and departure information by Track 36 was replaced by an electromechanical display in the main concourse over the ticket windows that displayed times and track numbers of arriving and departing trains.[28] Dubbed a Solari board after its Italian manufacturer, it contained rows of flip panels that displayed train information, and became a New York institution, as its many displays would flap simultaneously to reflect changes in train schedules, an indicator of just how busy Grand Central was. A small example of this type of device hangs in the Museum of Modern Art as an example of outstanding industrial design.

The flap-board destination sign was replaced with high-resolution mosaic LCD modules[29] also manufactured by Solari Udine. Similar modules are now also used on the trains, both on the sides to display the destination, and on the interior to display the time, next station, station stops, and other passenger information.

For safety reasons, every train at Grand Central Terminal departs one minute later than its posted departure time. The extra minute is intended to encourage passengers rushing to catch trains at the last minute to slow down. According to The Atlantic, Grand Central Terminal has the lowest rate of slips, trips, and falls on its marble floors, compared to all other stations in the U.S. with similar flooring.[30]

In December 2017, as part of the Customer Service Initiative, the MTA awarded contracts to replace the display boards and public announcement systems at Grand Central Terminal, as well as at 20 other Metro-North stations in New York State. The next-train departure time screens will be replaced with LED signs, and new cables, announcement systems, and security cameras would also be installed.[31]

Ceiling

The Main Concourse has an elaborately decorated astronomical ceiling,[32]:57 conceived in 1912 by Warren with his friend, French portrait artist Paul César Helleu, and executed by James Monroe Hewlett and Charles Basing of Hewlett-Basing Studio, with Helleu consulting.[33] Corps of astronomers and painting assistants worked with Hewlett and Basing. The original ceiling was replaced in the late 1930s to correct falling plaster.

There is a small dark circle amid the stars above the image of Pisces. In a 1957 attempt to counteract feelings of insecurity spawned by the Soviet launch of Sputnik, an American Redstone missile was set up in the Main Concourse. With no other way to erect the missile, the hole was cut to allow a cable to be lowered to lift the rocket into place. Historical preservation dictated that this hole remain (as opposed to being repaired) as a testament to the many uses of the Terminal over the years.

By the 1980s, the ceiling was obscured by decades of what was thought to be coal and diesel smoke. Spectroscopic examination revealed that it was mostly tar and nicotine from tobacco smoke. A 12-year restoration effort, completed in autumn 1996, restored the ceiling to its original design. A single dark patch above the Michael Jordan Steakhouse was left untouched by renovators to remind visitors of the grime that once covered the ceiling.

The starry ceiling is astronomically inaccurate in a complicated way. While the stars within some constellations appear correctly as they would from earth, other constellations are reversed left-to-right, as is the overall arrangement of the constellations on the ceiling. For example, Orion is correctly rendered, but the adjacent constellations Taurus and Gemini are reversed both internally and in their relation to Orion, with Taurus near Orion's raised arm where Gemini should be. One possible explanation is that the overall ceiling design might have been based on the medieval custom of depicting the sky as it would appear to God looking in at the celestial sphere from outside, but that would have reversed Orion as well. A more likely explanation is partially mistaken transcription of the sketch supplied by Columbia Astronomy professor Harold Jacoby. Though the astronomical inconsistencies were noticed promptly by a commuter in 1913, they have not been corrected in any of the subsequent renovations of the ceiling.[34]

Dining Concourse and lower level tracks

The Dining Concourse, below the Main Concourse and connected to it by numerous stairs, ramps, and escalators, provides access to the lower-level tracks. It has central seating and lounge areas, surrounded by restaurants. Among them is the Oyster Bar, the oldest business within Grand Central, whose decor includes vaults of Guastavino tile.

Vanderbilt Hall and Campbell Apartment

.jpg)

Vanderbilt Hall, named for the family that built and owned the station, serves as the entrance area from 42nd Street at Pershing Square. It sits next to the Main Concourse. Formerly the main waiting room for the terminal, it is now used for the annual Christmas Market and special exhibitions, and is rented for private events.

The Campbell Apartment is an elegantly restored cocktail lounge, just south of the 43rd Street/Vanderbilt Avenue entrance, that attracts a mix of commuters and tourists. It was at one time the office of 1920s tycoon John W. Campbell and replicates the galleried hall of a 13th-century Florentine palace.[35][36]

Vanderbilt Tennis Club and former studios

From 1939 to 1964, CBS Television occupied a large portion of the terminal building, particularly above the main waiting room. The space contained two production studios (41 and 42), two "program control" facilities (43 and 44), network master control, and facilities for local station WCBS-TV. In 1958, the world's first major videotape operations facility opened in a former rehearsal room on the seventh floor of the main terminal building. The facility used 14 Ampex VR-1000 videotape recorders. Douglas Edwards with the News broadcast from there for several years, covering among other events John Glenn's 1962 Mercury-Atlas 6 space flight. Edward R. Murrow's "See It Now" originated from Grand Central, including his famous broadcasts on Senator Joseph McCarthy. The Murrow broadcasts were recreated in George Clooney's movie Good Night, and Good Luck, although the CBS News and corporate offices were not actually in the same building as the film implies. The long-running panel show "What's My Line?" was first broadcast from the GCT studios, as were "The Goldbergs" and "Mama". The facility's operations were later moved to the CBS Broadcast Center.[37][38]

In 1966, the former studio space was converted to Vanderbilt Tennis Club, a sports club with two tennis courts.[39][37][38] It was once deemed as the most expensive place to play tennis, with tenants charged $58 an hour to play, until financial troubles forced the club to lower its fees to $40 an hour.[40] The club is so named because it is above the Vanderbilt Hall. Real estate magnate Donald Trump bought the club in 1984 after discovering the space while renovating the terminal's exterior.[41] Trump operated the club until 2009. The space is currently occupied by a conductor lounge and a smaller sports facility with a single tennis court.[37][38]

Subway station

The subway platforms at Grand Central are reached from the Main Concourse. Built by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT), the subway station consists of platforms for three lines, now operated by the MTA as part of the New York City Subway.

The IRT 42nd Street Shuttle platforms were originally an express stop on the original IRT subway, opened in 1904.[42] When the IRT Lexington Avenue Line was extended uptown in 1918, the original tracks were converted to shuttle use.[43] One track remains connected to the downtown Lexington Avenue local track but the connection is not in revenue service.[44] A fire in the 1960s destroyed much of the shuttle station, and it was later rebuilt.[45] There are also two other platform levels. The Lexington Avenue Line's platforms are located under the southeastern corner of the Metro-North terminal building, to the east of and at a lower level than the shuttle platforms.[46] The platforms are sometimes called the "diagonal station" because they are oriented 45° from the rest of the Manhattan street grid.[47] The IRT Flushing Line platform is deeper than the IRT Lexington Avenue Line's platforms because it is part of the Steinway Tunnel, which descends under the East River to the east of Grand Central. It opened in 1915, three years before the Lexington Avenue Line platforms did.[48]

Grand Central North

Grand Central North, opened on August 18, 1999, provides access to Grand Central from 45th Street, 47th Street, and 48th Street.[49] It is connected to the Main Concourse through two long hallways that run parallel to the tracks on the upper level: the 1,000-foot (300 m) Northwest Passage and 1,200-foot (360 m) Northeast Passage.[50] Entrances are at the northeast corner of East 47th Street and Madison Avenue (Northwest Passage), northeast corner of East 48th Street and Park Avenue (Northeast Passage), and on the east and west sides of 230 Park Avenue (Helmsley Building) between 45th and 46th Streets. A fifth entrance opened in early 2012 on the south side of 47th Street between Park and Lexington Avenues.[51] The 47th Street passage provides access to the upper level tracks and the 45th Street passage provides access to the lower-level tracks. Elevator access is available to the 47th Street (upper level) passage from street level on the north side of E. 47th Street, between Madison and Vanderbilt Avenues. There is no elevator access to the actual train platforms from Grand Central North; handicapped access is provided through the main terminal.

Throughout these passages, there is an Arts for Transit mosaic installation by Ellen Driscoll, an artist from Brooklyn.[50]

The entrances to Grand Central North were originally open from 6:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. Monday through Friday and 9 a.m. to 9:30 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. In summer 2006, Grand Central North was closed on weekends, with the MTA citing low usage and the need to save money.[52] Before it was closed, about 6,000 people used Grand Central North on a typical weekend,[53] and about 30,000 on weekdays.

Ideas for a northern entrance to Grand Central had been discussed since at least the 1970s. Construction on Grand Central North lasted from 1994 to 1999 and cost $75 million.[50] Delays were attributed to the incomplete nature of the original blueprints of Grand Central and previously undiscovered groundwater beneath East 45th Street. As of 2007, the passages are not air-conditioned.

The passages in the terminal are the Metro-North Railroad upper level; the Northwest and Northeast passages; the cross-passages at 47th and 45th Streets; and the Metro-North Railroad lower level.

Platforms and tracks

The terminal has the most platforms in any railway station in the world, with 44 platforms.[54][55] As of 2016, there are 67 tracks in regular passenger use, serving the Metro-North.[56] The upper level has 42 tracks, including ten tracks currently used only for storage. A balloon loop track encircles 40 of these tracks.[57] The lower level has 27 tracks circled by several balloon loops.[58] Tracks 116–125 on the Metro-North's lower level are being demolished to make room for the Long Island Rail Road concourse being built under the Metro-North station as part of the East Side Access project.[59]

East Side Access is building an additional four platforms and eight tracks numbered 201–204 and 301–304 in two double-decked caverns 100-foot-deep (30 m) underneath the ground.[60] The new LIRR station will have four tracks and two platforms in each of two caverns, and each cavern would contain two tracks and one platform on each level. A concourse will be located between the LIRR's two track levels.[61][62]

Underneath the Waldorf-Astoria (and connected to Grand Central via the tracks) is a private platform, Track 61, which was built mainly for former United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[63] He would travel into the city using his personal train into Track 61, then take a specially designed elevator to the surface. It has been used occasionally since Roosevelt's death.[64][65] This platform was part of the original design of the Waldorf Astoria.[17][32]:67 It was mentioned in The New York Times in 1929 and first used by General Pershing in 1938.[66]

History

Three buildings serving essentially the same function have stood on this site. The current building's large and imposing scale was intended by New York Central to compete, and compare favorably in the public eye, with its archrival, the Pennsylvania Railroad and its now-destroyed Pennsylvania Station (1910–1963), itself an architectural masterpiece.

Grand Central Depot

Grand Central Depot brought the trains of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad, and the New York and New Haven Railroad together in one large station. The station was designed by John B. Snook and financed by Cornelius Vanderbilt. Grand Central Depot first opened in October 1871. The original plan was for the Harlem Railroad to start using it on October 9, 1871 (moving from their 27th Street depot), the New Haven Railroad on October 16, and the Hudson River Railroad on October 23, with the staggering done to minimize confusion. However, the Hudson River Railroad did not move to it until November 1, which puts the other two dates in doubt.[67][68][69][70]

The head house containing passenger service areas and railroad offices was an "L" shape with a short leg running east-west on 42nd Street and a long leg running north-south on Vanderbilt Avenue. The train shed, north and east of the head house, had three innovations in U.S. practice: the platforms were elevated to the height of the cars, the roof was a balloon shed with a clear span over all of the tracks, and only passengers with tickets were allowed on the platforms (a rule enforced by ticket examiners). The Harlem, Hudson, and New Haven trains were initially in different stations that were adjacent to each other, which created chaos in baggage transfer. The combined Grand Central Depot serviced all three railroads.[70]

Grand Central Station

Between 1899 and 1900, the head house was renovated extensively.[23][24] It was expanded from three to six stories with an entirely new façade, on plans by railroad architect Bradford Gilbert. The train shed was kept, but the tracks that previously continued south of 42nd Street were removed and the train yard reconfigured in an effort to reduce congestion and turn-around time for trains.[71] The reconstructed building was renamed Grand Central Station.[23][24]

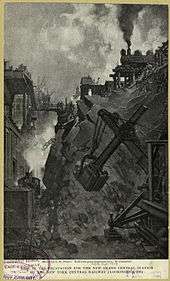

On January 8, 1902, a fatal train crash occurred in the Park Avenue Tunnel, north of the station. A southbound train had overrun several signals and collided with another southbound train, killing 15 people and injuring many more.[23][24][72] This event prompted William J. Wilgus, the chief engineer of New York Central, to think about alternatives to running a large railway yard in a growing metropolis.[23][24]

On December 22 of that year, Wilgus wrote a letter to New York Central president W. H. Newman, recommending that Grand Central Station, which served steam trains at the time, be completely replaced with a terminal for electric trains. Wilgus stated that electric trains were cleaner, faster, and cheaper to repair.[23][24] In addition, real estate could be built over the 16-block open cut in which Grand Central Station was located. Wilgus proposed a 12-story, 2,300,000-square-foot (210,000 m2) building over the terminal to offset the cost of the station, for a total profit of $2.3 million per year from rents.[23][24] The terminal was to cost $35 million and New York Central made most of its profit from freight, but the railroad's board of directors, including Cornelius Vanderbilt II, William K. Vanderbilt, William Rockefeller, and J. P. Morgan, approved the project on June 30, 1903.[23][24]

Replacement

Between 1903 and 1913, the entire building was torn down in phases and replaced by the current Grand Central Terminal. It was to be the biggest terminal in the world, both in the size of the building and in the number of tracks.[23][24] Before construction even started, objections were raised about the fact that dozens of buildings, on a 17-acre (6.9 ha) plot of land, had to be razed to build the terminal. Wilgus was to head the project.[23][24] Wilgus started to figure out ways to build the new terminal efficiently.[23][24] His solution was to demolish the old Grand Central Station and build the new terminal in sections, while some station operations were shifted to the Grand Central Palace Hotel for a while. This doubled the cost of construction, but obviated the need to suspend all rail service for the duration of construction.[23][24]

Design competition

Across town, Pennsylvania Station was being built by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which had started building its station and the North River Tunnels in 1901.[23][24] Wilgus wanted the new Grand Central Terminal's design to compete with Penn Station's similarly grand design, which was being built by McKim, Mead & White. Therefore, in 1903, New York Central set up a design competition to decide the firms who would design the new terminal. Wilgus already had abstract concepts for the new terminal and knew some design flaws in the old depot that he wanted to remove in the new terminal.[23][24]

Although many architects and firms entered the competition, only two won—Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore. Reed & Stem, from St. Paul, Minnesota, had won the contract in part because of their experience designing railway stations, and in part because one of the partners, Allen Stem, was Wilgus's brother-in-law. Similarly, Warren & Wetmore, the architects of the New York Yacht Club building, had Whitney Warren, the cousin of William Vanderbilt, as one of its partners.[23][24] Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore entered an agreement to act as the associated architects of Grand Central Terminal in February 1904. Reed & Stem were responsible for the overall design of the station, while Warren and Wetmore added architectural details and the Beaux-Arts style.[23][24] Charles Reed was appointed the chief executive for the collaboration between the two firms, and he promptly appointed Alfred T. Fellheimer as head of the combined design team. The team, called Associated Architects of Grand Central Terminal, had a tense relationship due to constant design disputes.[23][24] Warren & Wetmore's plan, for instance, removed the potentially-profitable tower above the terminal as well as vehicular viaducts around the depot.[23][24]

Construction

The construction project was enormous. About 3,200,000 cubic yards (2,400,000 m3) of the ground were excavated at depths of up to 10 floors, with 1,000 cubic yards (760 m3) of debris being removed from the site on 300 cars every day. The average construction site was 45 feet (14 m) deep, with the lower level being 40 feet (12 m) below ground.[23][24] Over 10,000 workers were assigned to put 118,597 short tons (107,589 t) of steel and 33 miles (53 km) of track inside the final structure. In addition, a 0.5-mile-long (0.80 km), 6-foot-wide (1.8 m) drainage tube was sunk 65 feet (20 m) under the ground to the East River.[23][24]

In 1906–7, the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad and the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad electrified their tracks with third rail on the approaches to Grand Central Terminal. This allowed electric trains to enter the then-future Grand Central Terminal upon its completion.[23][24] On September 30, 1906, the first electric train departed for the soon-to-be-demolished Grand Central Station from Highbridge, Bronx.[23][24]

To accommodate ever-growing rail traffic into the restricted Midtown area, Wilgus took advantage of the recent electrification technology to propose a novel scheme: a bi-level station below ground. Arriving trains would go underground under Park Avenue, and proceed to an upper-level incoming station if they were mainline trains, or to a lower-level platform if they were suburban trains.[23][24] In addition, turning loops within the station itself obviated complicated switching moves to bring back the trains to the coach yards for servicing. Departing mainline trains reversed into upper-level platforms in the conventional way.[23][24] New track infrastructure allowed maximum train speeds of 52 miles per hour (84 km/h), as well as a massive four-floor, 400-lever signal tower to control the suburban trains.[23][24]

Burying electric trains underground brought an additional advantage to the railroads: the ability to sell above-ground air rights over the tracks and platforms for real-estate development. The result of this was the creation of several blocks worth of prime real estate in Manhattan, which were then sold for a large sum of money. In addition, the terminal itself contains support structures for a possible future tower to be built above it.[23][24] The terminal also did away with bifurcating Park Avenue by introducing a "circumferential elevated driveway" that allowed Park Avenue traffic to traverse around the building and over 42nd Street without encumbering nearby streets. The building was also designed to accommodate reconnecting both segments of 43rd Street by going through the concourse had the City of New York demanded it.[23][24]

The last train left Grand Central Station at midnight on June 5, 1910, and workers promptly began demolishing the old station.[23][24] Plans for the new terminal were filed in January 1911. At the time, the proposals for Grand Central Terminal were spread out among 55 architects' drawings, marking one of the most comprehensive sets of plans that had ever been submitted to the New York City Department of Buildings.[73]

On December 20, 1910, a gas explosion at the station killed 10 people and injured 117 more.[74]

On February 2, 1913, the new terminal was opened, with passengers boarding the first train at one minute past midnight.[75][23][24][76][77] Within sixteen hours of opening, there were an estimated 150,000 visitors.[23][24]

Innovations

Grand Central Terminal was much larger than Penn Station, although the latter had been the first to open.[23][24] The former had 70-acre (28 ha) railyards, while the latter had only 28-acre (11 ha). Grand Central had 46 tracks and 30 platforms, more than twice Penn Station's 21 tracks and 11 platforms. In addition, the $43 million Grand Central Terminal had twice as much masonry and steel than Penn Station did, with another $800,000 for a roof that could potentially support a skyscraper in the future.[23][24] The new terminal also had a balloon loop for trains to turn around without reversing out of the station. The station building was 800 feet (240 m) long, 300 feet (91 m) wide, and 105 feet (32 m) high.[78]

Designers of the new terminal also tried to make it as comfortable as possible. To that end, amenities included an oak-floored waiting room for women, attended to by maids; a shoeshine room, also for women; a room with telephones; a salon with gender-separated portions; a dressing room, with maids available for a fee; and a men's barbershop for men, containing a public portion with barbers from many cultures, as well as a rentable private portion.[77][23][24] As part of the plans, Grand Central was also going to have two concourses, one on each level. The "outbound" concourse would have a 15,000-person capacity while the "inbound" concourse would have an 8,000-person capacity. A waiting room adjoining each concourse could fit another 5,000 people.[78] Brochures advertised the new Grand Central Terminal as a tourist-friendly space where "[t]imid travelers may ask questions with no fear of being rebuffed by hurrying trainmen, or imposed upon by hotel runners, chauffeurs or others in blue uniforms"; a safe and welcoming place for people of all cultures, where "special accommodations are to be provided for immigrants and gangs of laborers"; and a general tourist attraction "where one delights to loiter, admiring its beauty and symmetrical lines — a poem in stone".[23][24]

"Grand Central Zone"

The construction of Grand Central created a mini-city called the "Grand Central Zone", which stretched from 42nd to 51st Streets between Madison and Lexington Avenues. This area included the Commodore, Biltmore, Roosevelt, Marguery, Chatham, Barclay, Park Lane and Waldorf Astoria Hotels, luxury apartment houses along Park Avenue, and various new office buildings. Prestigious apartment and office buildings were erected around Grand Central, which turned the area into the most desirable commercial office district in Manhattan.[79][80][81] It spurred construction throughout the neighborhood in the 1920s, including that of skyscrapers such as the Chrysler Building.

In 1928, New York Central built its headquarters in a 34-story building (now called the Helmsley Building) straddling Park Avenue on the north side of the Terminal.

Grand Central Art Galleries

From 1922 to 1958, Grand Central Terminal was the home of the Grand Central Art Galleries, which were established by John Singer Sargent, Edmund Greacen, Walter Leighton Clark, and others.[82] The founders had sought a location in Manhattan that was central and easily accessible, and Alfred Holland Smith, president of New York Central, made the top of the terminal available. A 10-year lease[83] was signed, and the galleries, together with the railroad company, spent more than $100,000 to prepare the space.[84] The architect was William Adams Delano, best known for designing Yale Divinity School's Sterling Quadrangle.

At their opening, the galleries extended over most of the terminal's sixth floor, 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2), and offered eight main exhibition rooms, a foyer gallery, and a reception area.[85] A total of 20 display rooms were planned for what was intended as "... the largest sales gallery of art in the world".[84] The official opening was March 22, 1923,[85] and featured paintings by Sargent, Charles W. Hawthorne, Cecilia Beaux, Wayman Adams, and Ernest Ipsen. Sculptors included Daniel Chester French, Herbert Adams, Robert Aitken, Gutzon Borglum, and Frederic MacMonnies. The event attracted 5,000 people and received a glowing review from The New York Times.

A year after they opened, the galleries established the Grand Central School of Art, which occupied 7,000 square feet (650 m2) on the seventh floor of the east wing of the terminal. The school was directed by Sargent and Daniel Chester French. Its first-year teachers included painters Jonas Lie and Nicolai Fechin, sculptor Chester Beach, illustrator Dean Cornwell, costume designer Helen Dryden, and muralist Ezra Winter.[86][87] The Grand Central School of Art remained in the east wing until 1944.[88]

The Grand Central Art Galleries remained in the terminal until 1958, when they moved to the Biltmore Hotel.[89] They remained at the Biltmore for 23 years, until it was converted into an office building.[90] When the Biltmore was demolished in 1981, they moved to 24 West 57th Street.[91] They ceased operations in 1994.

Musical performances

Beginning during the Christmas season of 1928 and continuing on certain holidays until 1958, an organist performed in Grand Central's North Gallery. The organist was Mary Lee Read, who initially performed on a borrowed Hammond organ. Grand Central management eventually bought an organ and a set of chimes for the station and began paying Read an annual retainer.[92] In addition to the weeks before Christmas, Read played during the weeks before Thanksgiving and Easter and on Mother's Day. On one Easter, a choir composed of Works Progress Administration employees performed with her.[92] Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, she attempted to lift spirits by playing "The Star-Spangled Banner", which brought the main concourse to a standstill. The stationmaster subsequently asked her to avoid selections that would cause passengers to miss their trains, and Read became known as the only organist in New York who was forbidden to play the United States' national anthem.[92] On September 7, 2018, Paul McCartney performed a secret live show at Grand Central Terminal on the premiere date of his new album Egypt Station.[93]

Proposals for demolition and towers

In 1947, over 65 million people, or equivalent to 40% of the United States' population at the time, traveled through Grand Central. However, railroad traffic soon declined with competition from highways and intercity airline traffic.

Grand Central was designed to support a tower built above it. In 1954, William Zeckendorf proposed replacing Grand Central with an 80-story, 4,800,000-square-foot (450,000 m2) tower, 500 feet (150 m) taller than the Empire State Building. I. M. Pei created a pinched-cylinder design that took the form of a glass cylinder with a wasp waist. The plan was abandoned. In 1955, Erwin S. Wolfson made his first proposal for a tower north of the Terminal replacing the Terminal's six-story office building. A revised Wolfson plan was approved in 1958 and the Pan Am Building (now the MetLife Building) was completed in 1963 even though that section of the superstructure was not designed to support a tower above it.

Although the Pan Am Building's completion averted the terminal's imminent destruction, New York Central continued its precipitous decline. In 1968, facing bankruptcy, it merged with the Pennsylvania Railroad to form the Penn Central Railroad. The Pennsylvania Railroad was in its own precipitous decline, and in 1964, despite efforts to save the ornate Penn Station from destruction, the station was demolished and completely rebuilt to make way for an office building and the new Madison Square Garden. In 1968, Penn Central unveiled plans to build over Grand Central a tower even bigger than the Pan Am Building. The Marcel Breuer design would have used the existing building's tower support structure but would have destroyed the facade and the Main Waiting Room. The plans drew huge opposition, most prominently from Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis:

Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud monuments, until there will be nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? If they are not inspired by the past of our city, where will they find the strength to fight for her future? Americans care about their past, but for short term gain they ignore it and tear down everything that matters. Maybe... this is the time to take a stand, to reverse the tide, so that we won't all end up in a uniform world of steel and glass boxes.[94]

— Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Six months before the Breuer plans were unveiled, however, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated Grand Central a city "landmark". Penn Central was unable to secure permission from the Commission to execute either of Breuer's two blueprints. The railroad sued the city, alleging a taking.[95] The resulting case, Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City (1978), was the first time that the Supreme Court ruled on a matter of historic preservation. The Court saved the terminal, holding that New York City's Landmarks Preservation Act did not constitute a "taking" of Penn Central's property under the Fifth Amendment and was a reasonable use of government land-use regulatory power.

Penn Central went into bankruptcy in 1970 in what was then the biggest corporate bankruptcy in American history. Most of its railroad operations were taken over by Conrail in 1976, but Penn Central retained title to Grand Central Terminal. When Penn Central reorganized as American Premier Underwriters (APU) in 1994, it retained ownership of Penn Central. In turn, APU was absorbed by American Financial Group).

Restorations and expansion

1970s restoration

Grand Central and the surrounding neighborhood fell on hard times during the financial collapse of its host railroads and the near bankruptcy of New York City itself.

In 1975, Donald Trump bought the Commodore Hotel to the east of the terminal for $10 million and then worked out a deal with Jay Pritzker to transform it into one of the first Grand Hyatt hotels.[96] Trump negotiated various tax breaks and, in the process, agreed to renovate the exterior of the terminal.[97] The complementary masonry from the Commodore was covered with a mirror-glass "slipcover" façade – the masonry still exists underneath. In the same deal, Trump optioned Penn Central's rail yards on the Hudson River between 59th and 72nd Streets that eventually became Trump Place, the biggest private development in New York City.

In order to improve passenger flow, a new passageway at Grand Central was opened in May 1975.[98]

On September 11, 1976, a group of Croatian nationalists planted a bomb in a coin locker at Grand Central Terminal. The group also hijacked a plane. After stating their political demands, they revealed the location and provided the instructions for disarming the Grand Central Terminal bomb. The disarming operation was not executed properly and the resulting explosion wounded over 30 and killed one NYPD bomb squad specialist.[99][100]

The Grand Hyatt opened in 1980 and the neighborhood immediately began a transformation.[101] Trump sold his half-share in the hotel for $142 million in 1996.[102]

Throughout this period, the interior of Grand Central was dominated by huge billboard advertisements, with perhaps the most famous being the giant Kodak Colorama photos that ran along the entire east side, and the Westclox "Big Ben" clock over the south concourse.

Metro-North operation and 1990s restoration

Amtrak announced that it would stop service to the station in 1988.[103] The final Amtrak train stopped at the station on April 7, 1991, upon the completion of the Empire Connection, which allowed trains from Albany, Toronto, and Montreal to use Penn Station. Previously, travelers had to change stations via subway, bus, or cab. Since then, Grand Central has mostly served Metro-North Railroad, except for limited Empire Service Amtrak trains in the summer of 2017 and all Empire Service trains for summer of 2018, with the addition of the Maple Leaf, Ethan Allen Express, and Adirondack train services.[104][105]

In 1988, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), the Metro-North's operator, commissioned a study of the Grand Central Terminal. The report found that parts of the terminal could be turned into a retail area, and the balconies could be used for "high-quality" restaurants. This would increase the terminal's annual retail and advertising revenue from $8 million to $17 million. At the time, more than 80 million subway and Metro-North passengers used Grand Central Terminal every year, but eight of 73 storefronts were empty, and almost three-quarters of leases were set to expire by 1990.[106] The MTA signed a 280-year lease in 1994. The agency announced a renovation of terminal, in January 1995. The $113.8 million renovation would be the most extensive rehabilitation to the terminal since its opening in 1913. Of the projected cost, $30 million was to come from the Metro-North's capital allocation, while the other $84 million was to be raised through the sale of bonds. The MTA expected that the terminal's renovation would be completed in 1998, and that the retail space would net $13 million in annual revenue in 1999, which would increase to $17.5 million in 2009.[107]

During this renovation, all billboards were removed and the station was restored. These renovations were mostly finished in 1998, though some of the minor refits (such as replacement of electromechanical train information displays with electronic displays at track entries) were not completed until 2000. The most striking effect was the restoration of the Main Concourse ceiling, revealing the painted skyscape and constellations. The original baggage room, later converted into retail space and occupied for many years by Chemical Bank, was removed, and replaced with a mirror image of the West Stairs. Although the baggage room had been designed by the original architects, the restoration architects found evidence that a set of stairs mirroring those to the West was originally intended for that space. Other modifications included a complete overhaul of the Terminal's superstructure and the replacement of the electromechanical Omega Board train arrival/departure display with a purely electronic display that was designed to fit into the architecture of the Terminal aesthetically. The original quarry in Tennessee was located and reopened specifically to provide matching stone to replace damaged stone and for the new East Staircase. Each piece of new stone is labeled with its installation date and the fact that it was not a part of the original Terminal building.

The exterior was again cleaned and restored, starting with the west facade on Vanderbilt Avenue and gradually working counterclockwise. The project involved cleaning the facade, rooftop light courts, and statues; filling in cracks, repointing stones on the facade, restoring the copper roof and the building's cornice, repairing the large windows of the Main Concourse, and removing the remaining blackout paint applied to the windows during World War II. The result of the restoration, which was completed in 2007, was a cleaner, more attractive, and structurally sound exterior, and the windows now allow much more light into the Main Concourse.

Centennial

Midtown TDR Ventures, LLC, an investment group controlled by Argent Ventures,[108] purchased the station from American Financial in December 2006.[109] As part of the transaction the lease with the MTA was renegotiated through February 28, 2274. The MTA pays $2.24 million in rent and has an option to buy the station and tracks in 2017, although Argent could extend the date another 15 years to 2032.[108] The transferable air rights remain the property of Midtown TDR Ventures.

On February 1, 2013, numerous displays, performances and events were held to celebrate the terminal's centennial.[110][111]

In 2014, the One Vanderbilt supertall skyscraper was proposed for a site to the west of Grand Central Terminal, across Vanderbilt Avenue.[112] Demolition of the existing buildings on the site began in 2015.[113] The official groundbreaking was in October 2016[114] and the building is expected to be completed in 2020.[115] Its construction includes an underground connection to Grand Central Terminal.[114]

Long Island Rail Road access

.jpg)

The MTA is in the midst of a large-scale project to bring Long Island Rail Road trains into the terminal via the East Side Access Project. The project was spurred by a study that showed that more than half of LIRR riders work closer to Grand Central than to the current terminus at Penn Station.[116] The East Side Access has resulted in major blasting work under Grand Central Terminal. Since March 2007, about 1000 workers have completed more than 2,400 controlled blasts ending about October 4, 2013.[117]

A new bi-level, eight-track tunnel with four platforms was excavated under Park Avenue, more than 90 feet (27 m) below the Metro-North tracks and more than 140 feet (43 m) below the surface. Reaching the street from the lowest level, more than 175 feet (53 m) deep, will take about 10 minutes.[118] There will also be a new 350,000-square-foot retail and dining concourse.[119] It will initially be accessed via stairwells, 22 elevators, and 47 escalators connecting to Grand Central's existing food court, in comparison to the 19 escalators in the remainder of the LIRR system.[120] The MTA plans to build and open additional entrances at 45th, 46th, and 48th streets.[121] The escalators would be up to 180 feet (55 m) long. The escalators and elevators are to be partially privately operated, one of the only such instances in the entire MTA system.[120]

LIRR trains will access Park Avenue via the existing lower level of the 63rd Street Tunnel, connecting to its main line running through Sunnyside Yard in Queens. Extensions were added on both the Manhattan and Queens sides.

Cost estimates jumped from $4.4 billion in 2004 to $6.4 billion in 2006. The MTA said that some small buildings on the route in Manhattan will be torn down to make way for air vents.[122] Cardinal Edward Egan criticized the plan, noting concerns about the tracks, which will largely be on the west side of Park Avenue, and their impact on St. Patrick's Cathedral.[122] The new LIRR terminal will be open in December 2023.[123]

Influence on design of transit centers

Grand Central Terminal was an innovation in transit-hub design and continues to influence designers. One new concept was the use of ramps, rather than staircases, to conduct passengers and luggage through the facility. Another was wrapping Park Avenue around the Terminal above the street, creating a second level for picking up and dropping off passengers.

Grand Central Terminal was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976.[3][124][125]

Among the buildings modeled on Grand Central's design is the Poughkeepsie station, on Metro-North's Hudson Line in Poughkeepsie, New York. It was also designed by Warren & Wetmore and opened in 1918.[126]

Sister stations

Grand Central has a "sister station" agreement with Tokyo Station in Japan[127] and Hsinchu TRA station in Taiwan.[128]

In popular culture

Many film and television productions have included scenes shot at Grand Central Terminal. Kyle McCarthy, who handles production at Grand Central, said, "Grand Central is one of the quintessential New York places. Whether filmmakers need an establishing shot of arriving in New York or transportation scenes, the restored landmark building is visually appealing and authentic."[129]

The Terminal is the setting for Fiona Davis's 2018 historical fiction novel, "The Masterpiece."

In American vocabulary, the term Grand Central Station can be used to refer to a busy and overcrowded place.[130]

See also

- Architecture of New York City

- Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City

- Pennsylvania Station (New York City)

- Track 61 (New York City), a private track under Grand Central Terminal

- Transportation in New York City

References

Explanatory notes

- ↑ A railroad "terminal" such as Grand Central Terminal, the former Reading Terminal in Philadelphia, and the Los Angeles Union Passenger Terminal is a facility at the end of a rail line, which trains enter and depart in the same direction. A railroad station, such as Pennsylvania Station on the West Side, 30th Street Station in Philadelphia, and Union Station in Washington, D.C., is a facility along one or more contiguous rail lines, which trains can enter and depart in different directions.

Citations

- ↑ National Railroad Passenger Corporation. "New York, New York Grand Central Terminal". Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ↑ National Park Service (2007-01-23). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "Grand Central Station". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 11, 2007. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007.

- ↑ Middleton, William D. "Grand Central: The World's Greatest Railway Terminal", San Marino, California: Golden West Books (1977) p. 7

- ↑ Cannadine, David. "A Point of View: Grand Central, the world's loveliest station", BBC, February 8, 2013, accessed May 8, 2014

- ↑ https://tools.usps.com/go/POLocatorDetailsAction!input.action?locationTypeQ=all&address=10017-9998+&radius=1&locationType=po&locationID=1365295&locationName=GRAND+CENTRAL&address2=&address1=450+LEXINGTON+AVE+FL+2&city=NEW+YORK&state=NY&zip5=10017&zip4=9998&latitude=40.7533805&longitude=- 73.974724

- ↑ Dunlap, David (March 5, 2014). "At Trade Center Transit Hub, Vision Gives Way to Reality". The New York Times.

- ↑ Cannadine, David (February 8, 2013). "A Point of View: Grand Central, the world's loveliest station". BBC News. Retrieved February 8, 2013.

- ↑ Ann Shields (November 10, 2014). "The World's 50 Most Visited Tourist Attractions". Travel+Lesiure. Retrieved July 18, 2015.

- ↑ Haughney, Christine (July 25, 2011). "More Crowded Crowds: Grand Central to Welcome Apple and Shake Shack". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ↑ Hugh Merwin (October 2, 2013). "7 Things You Should Know About Shake Shack Grand Central, Opening Saturday". GrubStreet. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Apple Store Grand Central Opens Friday, December 9" (Press release). Apple. December 7, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Grand Central Terminal Directory Listing". Grand Central Terminal. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "The Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal". Untapped Cities.

- ↑ "New York". Cities of the Underworld. Season 1. Episode 107. June 4, 2007. History. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ Inside Grand Central. National Geographic Video. 2005. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- 1 2 "Neglected and rusting deep below Grand Central station, the armoured train that helped heroic Roosevelt keep his polio secret". Daily Mail. March 4, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Nuclear Radiation and Health Effects". World Nuclear Association. December 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ↑ Formerly Utilized Sites Remedial Action Program (August 1998). "Radiation in the Environment". US Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ↑ Gale, Robert Peter; Lax, Eric (2013). Radiation: What It Is, What You Need to Know. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 190. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ↑ "37587 – Decision". www.stb.dot.gov.

- ↑ "Air Rights Make Deals Fly". New York Post.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Roberts, Sam (January 18, 2013). "The Birth of Grand Central Terminal". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Sam Roberts (January 22, 2013). Grand Central: How a Train Station Transformed America. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4555-2595-9.

- ↑ Solomon, Brian; Mike Schafer (2007). New York Central Railroad. Saint Paul, MN: MBI and Voyageur Press. ISBN 9780760329283. OCLC 85851554.

- 1 2 3 4 "One Place Really Is as Busy as Grand Central Station: The Cliche Has the New York Terminal's Name Wrong, but Its Character Just Right". Los Angeles Times. (November 24, 1985). Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Schumach, Murray (January 20, 1954). "Central Derails its 4-Faced Clock". The New York Times. p. 29. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Grand Central's Departure Board, Gone!". The New York Times. July 23, 1996. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ "LCD signs and boards" (PDF). Solari di Udine. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ Garber, Megan (February 1, 2013). "The Clocks at Grand Central Station Are Permanently Wrong". The Atlantic.

- ↑ "Metro-North Railroad Committee Meeting" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. January 22, 2018. p. 108. Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- 1 2 Belle, John; Leighton, Maxinne Rhea (2000). Grand Central: Gateway to a Million Lives. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-04765-2.

- ↑ "Central Terminal Opening on Sunday". The New York Times. January 29, 1913. p. 13.

- ↑ "Constellations Reversed: New Grand Central Ceiling Has the Heavens Turned Around", The New York Times, March 23, 1913, p.10.

- ↑ "Campbell Apartment Bar in New York". Archived from the original on February 3, 2007.

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (January 9, 1994). "Grand Central Terminal; In a Forgotten Corner, a Curious Office of the 20's". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Sherman, William (March 19, 2009). "Donald Trump Bounced off Grand Central Tennis Deal". Daily News. New York. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Rubinstein, Dana (November 23, 2010). "A Tennis Court That Will Cost $210 an Hour". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ "A Look at the Hidden Tennis Courts of Grand Central Terminal, Once Leased by Trump". Untapped Cities. February 9, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ Friedman, Charles (1978). "Most Expensive Tennis Club Sheds Status Symbol". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- ↑ Schmidt, Michael S. (August 31, 2006). "Game, Set, Match Above the Roar of the City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Our Subway Open, 150,000 Try It — Mayor McClellan Runs the First Official Train — Big Crowds Ride At Night — Average of 25,000 an Hour from 7 P.M. Till Past Midnight — Exercises in the City Hall — William Barclay Parsons, John B. McDonald, August Belmont, Alexander E. Orr, and John Starin Speak — Dinner at Night". New York Times. October 28, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Shuttle Service In Operation". pudl.princeton.edu. Interborough Rapid Transit Company. September 27, 1918. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ↑ Dougherty, Peter (2018). Tracks of the New York City Subway 2018 (16th ed.). Dougherty.

- ↑ Buckley, Thomas (April 22, 1964). "Pavement in 42d Street at Grand Central Is Weakened by Early‐Morning Fire in the IRT Shuttle Station". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 15, 2016 – via New York Times Archive.

- ↑ "LEXINGTON AV. LINE TO BE OPENED TODAY; Subway Service to East Side of Harlem and the Bronx Expected to Relieve Congestion.BEGINS WITH LOCAL TRAINSRunning of Express Trains to AwaitOpening of Seventh AvenueLine of H System". The New York Times. July 17, 1918. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ↑ "CONTRACT FOR SUBWAY LINK: Award Made for Diagonal Station at Grand Central". The New York Times. October 10, 1914. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ↑ "STEINWAY TUNNEL WILL OPEN TODAY; Officials Will Attend Ceremony in the Long Island City Station at 11 A.M. FIRST PUBLIC TRAIN AT NOON Public Service Commission Renames the Under-River Route the Queensboro Subway". The New York Times. June 22, 1915. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- ↑ Finkelstein, Katherine E. (August 19, 1999). "Passageway Easing Exit Is Opened At Terminal". The New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Ames, Lynn (October 10, 1999). "The View From/Manhattan; A Shorter Commute". The New York Times. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ↑ "New Entrance to the Grand Central North Being Built On 47th Street Between Park and Lexington Avenues" (Press release). Metro-North Railroad. January 11, 2010. Retrieved June 29, 2010.

- ↑ "MTA Metro-North Railroad". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "MTA 2005 Preliminary Budget (7–29–04) – Volume 2 – MNR" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ Haikalis, George (November 11, 2006). "Regional Rail Working Group: Streamlining Access to Grand Central Terminal". Auto-free.org. Section entitled "What are MTA's objections to this streamlined plan?". Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Grand Central Terminal". nyctourist.com.

- ↑ "Unknown Grand Central Terminal, New York City, New York". Interesting America.

- ↑ Samson, Peter R. (2004). GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL, Upper Level (PDF).

- ↑ Samson, Peter R. (2004). GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL, Lower Level (PDF).

- ↑ "Grand Central Terminal Outline of Existing Tracks and Platforms" MTA.info

- ↑ "MTA OK's contract for East Side Access". TimesLedger. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- ↑ Dobnik, Verena (November 4, 2015). "Massive East Side Access Project Rolling On Under Grand Central". nbcnewyork.com. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ "East Side Access transforming the LIRR". Herald Community Newspapers. August 21, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ "The secret below Grand Central Station". BBC News. January 16, 2009. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ Joseph Brennan (2002). "Grand Central Terminal, Waldorf-Astoria platform". Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ↑ Forrest Wickman (May 1, 2014). "Is the Secret Subway in the New Spider-Man Real? Explained". Slate.

- ↑ "Grand Central Terminal, Waldorf-Astoria platform". Retrieved November 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Local News in Brief". The New York Times. September 29, 1871. p. 8. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ "The Grand Central Railroad Depot, Harlem Railroad". The New York Times. October 1, 1871. p. 6. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Local News in Brief". The New York Times. November 1, 1871. p. 8. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 Gray, Christopher (June 21, 1998). "Grand Central Terminal; How a Rail Complex Chugged Into the 20th Century". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (July 1, 2007). "The Architect Who Turned a Railroad Bridge on Its Head". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ↑ "WGBH American Experience . Grand Central". PBS. January 8, 1902. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ↑ "NEW TERMINAL PLANS FILED.; N.Y. Central Station Will Be a Most Imposing Structure" (PDF). The New York Times. 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "TEN KILLED, SCORES HURT IN EXPLOSION; Pintsch Gas Blast Brings Death and Ruin at the Grand Central Station" (PDF). The New York Times. December 20, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ Maranzani, Barbara. "Grand Central Terminal: An American Icon". History.com. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Grand Central Terminal opens". Railway Age. Simmons-Boardman Publishing: 78. September 2006. ISSN 0033-8826.

- 1 2 "Modern Terminal Supplies Patrons with Home Comforts". The New York Times. February 2, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- 1 2 "WONDERS GROW NEAR NEW GRAND CENTRAL; Work Will Cost $180,000,000 and a New Park Avenue Will Rise to the North" (PDF). The New York Times. June 26, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Grand Central Zone Boasts Many Connected Buildings", The New York Times, September 14, 1930

- ↑ "Exploring New York's Real Underworld".Popular Science Monthly, November 1931, p. 135

- ↑ The Gateway to a Contiinent: Grand Central Zone" 1939

- ↑ "Painters and Sculptors' Gallery Association to Begin Work". The New York Times. December 19, 1922. p. 19. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Grand Central Art Galleries Records". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- 1 2 "New Home for Art to Cost $100,000". The New York Times. March 11, 1923. p. E7. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- 1 2 "New Art Gallery Opens to Throng". The New York Times. March 22, 1923. p. 18. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ "New Art School Opens: Reception Held in Studios Over the Grand Central". The New York Times. October 2, 1924. p. 27. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Terminal Fire Not in Art School". The New York Times. September 6, 1929. p. 9. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ↑ "New Art School Opens: Reception Held in Studios Over the Grand Central". The New York Times. October 2, 1924. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ↑ "Galleries to End 36 Years in Depot", The New York Times, October 31, 1958

- ↑ "Retaining Order to Block Biltmore Demolition Expires", The New York Times, August 19, 1981

- ↑ Fraser, C. Gerald (April 22, 1986). "Going Out Guide". The New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Pollak, Michael (October 10, 2014). "Did Grand Central Terminal Have a Live Organist?". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ↑ "Paul McCartney plays surprise concert at New York's Grand Central Terminal". the Guardian. September 8, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ↑ Grand Central Station: The History of New York City's Famous Railroad Terminal. Charles River Editors. 2013. ISBN 978-1-5084-3504-4.

- ↑ Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York, 438 U.S. 104 (1978)

- ↑ Tomasson, Robert E. (May 4, 1975). "Deal Negotiated for Commodore". The New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ↑ Masello, Robert. "The Trump Card". Town & Country. Town & Country.

- ↑ "New Corridor Is Opened To Improve Grand Central". The New York Times. May 8, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Skyjackings: Bombs for Croatia". Time. September 20, 1976. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ↑ Katz, Samuel M. (2002). Relentless Pursuit: The DSS and the Manhunt for the Al-Qaeda Terrorists. New York: Forge/Tom Doherty Associates. p. 82. ISBN 0-7653-0402-3.

- ↑ Goldberger, Paul (September 22, 1980). "42nd Street Is About to Add Something New and Pleasant: the Grand Hyatt". The New York Times. Retrieved July 2, 2011.

- ↑ "History of The Trump Organization". Funding Universe. Retrieved March 30, 2016.

Trump sold his half-share in the Grand Hyatt Hotel to the Hyatt Corp. in 1996 for $142 million.

- ↑ Johnson, Kirk (July 7, 1988). "Amtrak Trains To Stop Using Grand Central". The New York Times. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ↑ "6 Amtrak trains to use Grand Central Terminal this summer". lohud.com. June 12, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ Rulison, Larry; Anderson, and Eric (April 10, 2018). "Repairs will shift Amtrak's Rensselaer trains to Grand Central Terminal". Times Union. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ↑ "PLAN URGES NEW LOOK AT TERMINAL By RICHARD LEVINE". The New York Times. 1988. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (January 29, 1995). "Grand Central Makeover Is Readied". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- 1 2 Weiss, Lois (July 6, 2007). "Air Rights Make Deals Fly". New York Post. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Midtown TDR Ventures LLC-Acquisition Exemption-American Premier Underwriters, Inc., The Owasco River Railway, Inc., and American Financial Group, Inc". Surface Transportation Board, U.S. Department of Transportation. December 7, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Grand Central Terminal". mta.info. February 1, 1913. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Grand Central turns 100". RT&S. February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (May 29, 2014). "65-Story Tower Planned Near Grand Central Terminal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ Cuozzo, Steve (March 15, 2016). "One Vanderbilt mega-office tower picking up steam". New York Post. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- 1 2 Chaban, Matt A. (October 16, 2016). "Future Neighbor Will Tower Over Grand Central, but Allow It to Shine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ Warerkar, Tanay (October 18, 2016). "One Vanderbilt reveals public plaza, huge transit hall in new renderings". Curbed NY. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Record of Decision (ROD) East Side Access Project" (PDF). US Department of Transportation. p. 5. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ↑ "MTA concludes blasting work under Grand Central Terminal". Progressive Railroading. October 4, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ "East Side Access Project, Final Environmental Impact Statement" (PDF). p. 22. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ↑ Dobnik, Verena (November 4, 2015). "Massive East Side Access Project Rolling On Under Grand Central". nbcnewyork.com. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- 1 2 Mann, Ted (April 26, 2012). "MTA Focuses on Ups, Downs". WSJ. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ↑ Ocean, Justin (November 4, 2015). "Inside the Massive New Rail Tunnels Beneath NYC's Grand Central". Bloomberg News. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- 1 2 Yates, Maura (February 10, 2005). "East Side Access Draws Opponents". The New York Sun. p. 1. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- ↑ Castillo, Alfonso A. (January 27, 2014). "East Side Access completion date extended – again". Newsday. Retrieved March 5, 2014.

The MTA's monumental East Side Access project to link the Long Island Rail Road to Grand Central Terminal could carry a price tag $2.6 billion over budget and not be completed until 2023, four years behind schedule, according to a new report.

- ↑ ""Grand Central Station" August 11, 1976, by Carolyn Pitts" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination. National Park Service. August 11, 1976.

- ↑ "Grand Central Station—Accompanying 11 photos, exterior and interior, from 1983 and undated" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Inventory. National Park Service. 1983.

- ↑ Howe, Patricia; Katherine Moore (February 25, 1976). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Poughkeepsie Railroad station". Retrieved January 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Tokyo and Frankfurt Central become sister stations". The Asahi Shimbun Asia & Japan Watch. The Asahi Shimbun Company. 26 September 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-09-27. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tokyo Station to get a sister station in Taiwan". The Japan Times. Japan: The Japan Times Ltd. 10 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ "Industry Star of the Month". Mayor's Office of Film, Theatre & Broadcasting. October 1, 2005. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Grand central station". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

Further reading

- "Designation List 137 LP-1099; Grand Central Terminal Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 23, 1980. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City: Vol 1, New York City Guide. US History Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1.

- Fitch, James Marston; Waite, Diana S. (1974). Grand Central Terminal and Rockefeller Center: A Historic-critical Estimate of Their Significance. Albany, New York: The Division.

- Fried, Frederick; Gillon, Edmund Vincent Jr. (1976). New York Civic Sculpture: A Pictorial Guide. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23258-1.

- Middleton, William D. (1999). Grand Central, the World's Greatest Railway Terminal. San Marino: Golden West Books. OCLC 49014602.

- O'Hara, Frank; Allen, Donald (1995). The Collected Poems of Frank O'Hara. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-520-20166-3.

- Reed, Henry Hope; Gillon, Edmund Vincent Jr. (1988). Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-25698-7.

- Schlichting, Kurt C. (2001). Grand Central Terminal: Railroads, Architecture and Engineering in New York. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6510-7.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0511-5.

External links

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Central Terminal. |