Wichita Falls, Texas

Wichita Falls (/ˈwɪtʃɪtɑː/ WITCH-i-tah) is a city in and the county seat of Wichita County, Texas, United States.[6] It is the principal city of the Wichita Falls Metropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Archer, Clay, and Wichita counties. According to the 2010 census, it had a population of 104,553, making it the 38th-most populous city in Texas. In addition, its central business district is 5 miles (8 km) from Sheppard Air Force Base, which is home to the Air Force's largest technical training wing and the Euro-NATO Joint Jet Pilot Training program, the world's only multinationally staffed and managed flying training program chartered to produce combat pilots for both USAF and NATO.

Wichita Falls, Texas | |

|---|---|

| City of Wichita Falls | |

The "restored Falls" of the Wichita River just off Interstate 44 | |

Flag | |

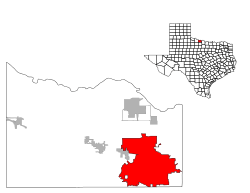

Location in the state of Texas | |

Wichita Falls Location in the state of Texas  Wichita Falls Wichita Falls (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 33°54′34″N 98°29′58″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Wichita |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Stephen Santellana (R)[1] |

| • City Council | Members

|

| • City Manager | Darron Leiker |

| • Deputy City Manager | Jim Dockery |

| Area | |

| • City | 70.1 sq mi (183.1 km2) |

| • Land | 70.66 sq mi (183.0 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.1 km2) |

| Elevation | 948 ft (289 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 104,553 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 104,683 |

| • Rank | US: 288th |

| • Density | 1,500/sq mi (570/km2) |

| • Urban | 99,437 (US: 301st) |

| • Metro | 151,201 (US: 268th) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 76301-11 |

| Area code(s) | 940 |

| FIPS code | 48-79000[5] |

| Interstates | |

| U.S. Routes | |

| Website | City of Wichita Falls |

The city is home to the Newby-McMahon Building (otherwise known as the "world's littlest skyscraper"), constructed downtown in 1919 and featured in Robert Ripley's Ripley's Believe It or Not!.

History

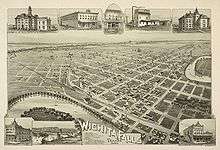

The Choctaw Native Americans settled the area in the early 19th century from their native Mississippi area once Americans negotiated to relocate them after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.[7] American settlers arrived in the 1860s to form cattle ranches. The city was officially titled Wichita Falls on September 27, 1876. On that day, a sale of town lots was held at what is now the corner of Seventh and Ohio Streets – the birthplace of the city.[8] The Fort Worth & Denver City Railway arrived in September 1882, the same year the city became the county seat of Wichita County.[7] The city grew westwards from the original FW&DC train depot which was located at the northwest corner of Seventh Street and the FW&DC.[8] This area is now referred to as the Depot Square Historic District,[9][10] which has been declared a Texas Historic Landmark.[11]

The early history of Wichita Falls well into the 20th century also rests on the work of two entrepreneurs, Joseph A. Kemp[12] and his brother-in-law, Frank Kell. Kemp and Kell were pioneers in food processing and retailing, flour milling, railroads, cattle, banking, and oil.[13]

A flood in 1886 destroyed the original falls on the Wichita River for which the city was named.[14] After nearly 100 years of visitors wanting to visit the nonexistent falls, the city built an artificial waterfall beside the river in Lucy Park. The recreated falls are 54 ft (16 m) high and recirculate at 3,500 gallons per minute. They are visible to south-bound traffic on Interstate 44.

The city is currently seeking funding to rebuild and restore the downtown area.[7] Downtown Wichita Falls was the city's main shopping area for many years, but lost ground to the creation of new shopping centers throughout the city beginning with Parker Square in 1953 and other similar developments during the 1960s and 1970s, culminating with the opening of Sikes Senter Mall in 1974.

Wichita Falls was once home to offices of several oil companies and related industries, along with oil refineries operated by the Continental Oil Company (now Conoco Phillips) until 1952 and Panhandle Oil Company American Petrofina) until 1965.[15] Both firms continued to use a portion of their former refineries as gasoline/oil terminal facilities for many years.

1964 tornado

A devastating tornado hit the north and northwest portions of Wichita Falls along with Sheppard Air Force Base during the afternoon of April 3, 1964. As the first violent tornado on record to hit the Wichita Falls area,[16] it left seven dead and more than 100 injured. Additionally, the tornado caused roughly $15 million in property damage with about 225 homes destroyed and another 250 damaged.[17] It was rated F5, the highest rating on the Fujita scale, but it is overshadowed by the 1979 tornado.[18]

1979 tornado

An F4 tornado struck the heavily populated southern sections of Wichita Falls in the late afternoon on Tuesday, April 10, 1979 (known locally as "Terrible Tuesday"). It was part of an outbreak that produced 30 tornadoes around the region. Despite having nearly an hour's advance warning that severe weather was imminent, 42 people were killed (25 in vehicles) and 1,800 were injured because it arrived just in time for many people to be driving home from work.[19] It left 20,000 people homeless and caused $400 million in damage, a U.S. record not topped by an individual tornado until the F5 Moore–Oklahoma City tornado of May 3, 1999.[20]

Geography and climate

Wichita Falls is about 15 miles (24 km) south of the border with Oklahoma, 115 mi (185 km) northwest of Fort Worth, and 140 mi (230 km) southwest of Oklahoma City. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 70.71 square miles (183.1 km2), of which 70.69 square miles (183.1 km2) are land and 0.02 square miles (0.052 km2) (0.03%) is covered by water.[21]

Wichita Falls experiences a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), featuring long, very hot and humid summers, and cool winters. The city has some of the highest summer daily maximum temperatures in the entire U.S. outside of the Desert Southwest. Temperatures have hit 100 °F (38 °C) as early as March 27 and as late as October 17, but more typically reach that level on 28 days annually, with 102 days of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher annually; the average window for the latter mark is April 9–October 10. However, 59 to 60 nights of freezing lows occur, and an average of 4.8 days where the high does not rise above freezing. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 42.0 °F (5.6 °C) in January to 84.4 °F (29.1 °C) in July. Extremes in temperature have ranged from −12 °F (−24 °C) on January 4, 1947, to 117 °F (47 °C) on June 28, 1980. Snowfall is sporadic and averages 4.1 in (10 cm) per season, while rainfall is typically greatest in early summer.

From 2010 through 2013 Wichita Falls, along with a large portion of the south-central US, experienced a persistent drought. In September 2011, Wichita Falls became the first Texas city[22] to have 100 days of 100 °F (38 °C), or higher, in one year.[lower-alpha 1]

During the 2015 Texas–Oklahoma floods, Wichita Falls broke its all-time record for the wettest month, with 17.00 inches of rain recorded in May 2015.[24]

| Climate data for Wichita Falls, Texas (1981–2010 normals, extremes 1923–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 87 (31) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

110 (43) |

117 (47) |

114 (46) |

113 (45) |

111 (44) |

102 (39) |

89 (32) |

88 (31) |

117 (47) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 54.2 (12.3) |

58.3 (14.6) |

67.0 (19.4) |

75.8 (24.3) |

83.6 (28.7) |

91.4 (33.0) |

96.9 (36.1) |

96.6 (35.9) |

88.1 (31.2) |

77.0 (25.0) |

65.1 (18.4) |

54.7 (12.6) |

75.7 (24.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 29.8 (−1.2) |

33.5 (0.8) |

41.2 (5.1) |

49.4 (9.7) |

59.6 (15.3) |

67.6 (19.8) |

71.9 (22.2) |

71.4 (21.9) |

63.3 (17.4) |

52.0 (11.1) |

40.3 (4.6) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

50.9 (10.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −12 (−24) |

−8 (−22) |

6 (−14) |

24 (−4) |

35 (2) |

50 (10) |

54 (12) |

53 (12) |

38 (3) |

21 (−6) |

14 (−10) |

−7 (−22) |

−12 (−24) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.14 (29) |

1.75 (44) |

2.20 (56) |

2.61 (66) |

3.79 (96) |

4.15 (105) |

1.59 (40) |

2.50 (64) |

2.81 (71) |

3.11 (79) |

1.65 (42) |

1.62 (41) |

28.92 (735) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.4 (3.6) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

trace | 0.3 (0.76) |

1.0 (2.5) |

3.9 (9.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 4.8 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 6.2 | 8.7 | 7.7 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 74.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 2.0 |

| Source: National Weather Service,[23][25] Weather.com[26] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 1,978 | — | |

| 1900 | 2,480 | 25.4% | |

| 1910 | 8,200 | 230.6% | |

| 1920 | 40,079 | 388.8% | |

| 1930 | 43,690 | 9.0% | |

| 1940 | 45,112 | 3.3% | |

| 1950 | 68,042 | 50.8% | |

| 1960 | 101,724 | 49.5% | |

| 1970 | 96,265 | −5.4% | |

| 1980 | 94,201 | −2.1% | |

| 1990 | 96,259 | 2.2% | |

| 2000 | 104,197 | 8.2% | |

| 2010 | 104,553 | 0.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 104,683 | [4] | 0.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] Texas Almanac: 1850–2000[28] 2018 Estimate[29] | |||

As of the census[5] of 2000, 104,197 people, 37,970 households, and 24,984 families resided in the city.[30] The population density was 1,474.1 inhabitants per square mile (569.2/km2). The 41,916 housing units averaged 593.0 per square mile (229.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 75.1% White, 12.4% African American, 0.9% Native American, 2.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 6.4% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 14.0% of the population.[30]

Of the 37,970 households, 33.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.7% were married couples living together, 12.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.2% were not families. About 28.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46, and the average family size was 3.04.[30]

In the city, the population was distributed as 24.7% under the age of 18, 15.2% from 18 to 24, 29.3% from 25 to 44, 18.6% from 45 to 64, and 12.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 106.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 106.7 males.[30]

The median income for a household in the city was $32,554, and for a family was $39,911. Males had a median income of $27,609 versus $21,877 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,761. About 10.8% of families and 13.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.7% of those under age 18 and 10.3% of those age 65 or over.[30]

Economy

Top employers

According to Wichita Falls Chamber of Commerce, the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sheppard Air Force Base | 7,222 |

| 2 | Wichita Falls Independent School District | 2,378 |

| 3 | United Regional Health Care System | 2,100 |

| 4 | Midwestern State University | 1,276 |

| 5 | City of Wichita Falls | 1,217 |

| 6 | Arconic | 1,072 |

| 7 | Walmart (3 locations) | 1,009 |

| 8 | North Texas State Hospital -Wichita Falls Campus | 1,000 |

| 9 | Vitro[31] | 934 |

| 10 | James V. Allred Unit[32] | 921 |

Media

Wichita Falls is part of a bi-state media market that also includes the nearby, smaller city of Lawton, Oklahoma. According to Nielsen Media Research estimates for the 2016–17 season, the market – which encompasses ten counties in western north Texas and six counties in southwestern Oklahoma, has 152,950 households with at least one television set, making it the 148th-largest television market in the United States; the market also has an average of 120,200 radio listeners ages 12 and over, making it the 250th largest radio market in the nation.[33][34]

Newspapers

- Times Record News (daily)

- Falls News Journal (daily)

Television stations

- KFDX-TV (channel 3; NBC)

- KAUZ-TV (channel 6; CBS, and digital subchannel 6.2; The CW)

- KSWO-TV (channel 7; ABC)

- KJTL (channel 18; Fox)

- KJBO-LP (channel 35; MyNetworkTV)

By default, KERA-TV out of Dallas–Fort Worth serves as the default PBS member station for Wichita Falls via a translator station on UHF channel 44.

Radio stations

- KWFS (1290 AM; news/talk radio)

- KMCU (88.7 FM; National Public Radio)

- KMOC (89.5 FM; Contemporary Christian)

- KZKL (90.5 FM; Contemporary Christian)

- KNIN (92.9 FM; CHR)

- KOLI (94.9 FM; Modern Country)

- KXPN-FM (95.5 FM; Classic Country)

- KXXN (97.5 FM; Classic Country)

- KLUR (99.9 FM; Country)

- KWFB (100.9 FM; Adult hits)

- KWFS-FM (102.3 FM; Modern Country)

- KQXC (103.9 FM; Rhythmic CHR)

- KYYI (104.7 FM; Classic rock)

- KBZS (106.3 FM; Active rock)

Sports and recreation

Recreation

Lake Wichita

Nearby Lake Wichita was dredged in 1901 at a cost of $175,000 through the efforts of entrepreneur Joseph Kemp. The 234-acre (95 ha) Lake Wichita Park is on the north shore of the lake. This park offers a 2.6-mile concrete hiking and bicycling trail that runs from the southern tip of the park at Fairway Avenue to the dam. The trail resumes northward to Lucy Park. The park has a playground, basketball courts, and multiple picnic areas. The 10-unit picnic shelter can seat 60 people and is available for rent. The park also has two lighted baseball and two lighted softball fields, three lighted football fields, and an 18-hole disc golf course. The park has the only model airplane landing strip in the Texas state park system. An off-leash dog park is available.[35]

Because of drought, the fish population in Lake Wichita has been damaged by golden algae blooms and periods of low dissolved oxygen. Therefore, the lake was not recommended in 2013 as a destination for fishing.[36] When available, the fish population consists mostly of white bass, hybrid striped bass, channel catfish, and white crappie. Camping facilities are also available.[37]

Lucy Park

Lucy Park is a 170-acre (69 ha) park with a log cabin, duck pond, swimming pool, playground, frisbee golf course, and picnic areas. It has multiple paved walkways suitable for walking, running, biking, or rollerskating, including a river walk that goes to a recreation of the original falls for which the city was named (the original falls were destroyed in a 19th-century flood; the new falls were built in response to numerous tourist requests to visit the "Wichita Falls"). It is one of 37 parks throughout the city. The parks range in size from small neighborhood facilities to the 258 acres of Weeks Park featuring the Champions Course at Weeks Park, an 18-hole golf course. In addition, an off-leash dog park is within Lake Wichita Park and a skatepark adjacent to the city's softball complex. Also, unpaved trails for off-road biking and hiking are available.

Hotter'N Hell Hundred

Wichita Falls is the home of the annual Hotter'N Hell Hundred, the largest single day century bicycle ride in the United States and one of the largest races in the world. The race started as a way for the city to celebrate its centennial in 1982. The race takes place over a weekend in August, and there are multiple events for people to participate in.[38]

Sports

In 2014, the Wichita Falls Nighthawks, an indoor football team, joined the Indoor Football League[39] but suspended operations after the 2017 season.

The city has also been home to a number of semi-professional, developmental, and minor league sports teams, including the Wichita Falls Drillers, a semi-pro football team that has won numerous league titles and a national championship; Wichita Falls Kings (formerly known as Wichita Falls Razorbacks), the professional basketball team Wichita Falls Texans of the Continental Basketball Association; Wichita Falls Fever in the Lone Star Soccer Alliance (1989–92); the Wichita Falls Spudders baseball team in the Texas League; the Wichita Falls Wildcats (formerly the Wichita Falls Rustlers) of the North American Hockey League, an American Tier II junior hockey league; and the Wichita Falls Roughnecks (formerly the Graham Roughnecks) of the Texas Collegiate League. The Dallas Cowboys held training camp in Wichita Falls during the late 1990s. However, the sustainability of minor or rookie league sports franchises in the Wichita Falls region have a questionable future.[40]

The Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame relocated to Wichita Falls from Amsterdam, New York, in November 2015.

Government

Local government

The mayor of Wichita Falls is Stephen Santellana, who was elected in 2016 and re-elected in 2018. The Wichita Falls City Council has six members: District 1-Stephen Santellana, District 2-DeAndra Chenault, District 3-Jeff Browning, District 4-Tim Ingle, District 5-Tom Quintero, and Councilor-at-Large-Michael Smith. The city manager is Darron Leiker.

- Otis T. Bacon, 1889-1892[41]

- J.Q. Morrison, 1892-1894

- Charles O. Joline, 1894-1898

- Charles W. Bean, 1900-1904

- T.B. Noble, 1904-1912

- Jonathan M. Bell, 1912-1914

- J.W. Bradley, 1914

- A.H. Britain, 1914-1918

- J.B. Marlow, 1918-1920

- Walter D. Cline, 1920-1922

- Frank Collier, 1922-1925

- R. E. Shepherd, 1925-1928

- J.W. Akin, 1928-1930

- Walter Nelson, Jr., 1930-1934

- J.T. Young, circa 1934-1936

- W.E. Fitzgerald, 1936-1942

- W.P. (Bill) Hood, 1942-1944

- W.B. Hamilton, 1944-1948

- Harold Jones, 1948-1952

- Kindall Paulk, 1952-1954

- Lloyd Thomas, 1954-1956

- K.C. Spell, 1956-1960

- Kenneth Johnson, 1960-1962

- John Gavin, 1962-1964

- Winston Wallander, 1964-1966

- R.C. "Dick" Rancier, 1966-1970

- R. Kenneth Hill, 1970-1974

- Max Kruger, 1974-1978

- Kenneth Hill, 1978-1984

- Gary Cook, 1982-1986

- Charles Harper, 1986-1988

- Perry Goolsby, 1988-1990

- Michael Lam, 1990-1996

- Kay Yeager, 1996-2000

- Jerry Lueck, 2000-2002

- William Altman, 2002-2005

- Arthur B. Williams, 2005

- Lanham Lyne, 2005-2010

- Glenn Barham, 2010-2016[42]

- Stephen Santellana, 2016–present

State and federal politics

Wichita Falls is located in the 69th district of the Texas House of Representatives. Lanham Lyne, a Republican, represented the district from 2011 to 2013; he was the mayor of Wichita Falls from 2005 to 2010. When Lyne declined to seek a second term in 2012, voters chose another Republican, James Frank. Wichita Falls is located in the 30th district of the Texas Senate. Craig Estes, a Republican, had held the senate seat since 2001, until Pat Fallon won election in 2018. Wichita Falls is part of Texas's 13th congressional district for the U.S. House of Representatives. Mac Thornberry, a Republican, has held this seat since 1995. The 13th District is considered the most conservative district in the country, according to the Cook Political Report 2018. Donald Trump won 80% of the vote in the 2016 election.

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice James V. Allred Unit is located in Wichita Falls, 4 mi (6.4 km) northwest of downtown Wichita Falls. The prison is named for former Governor James V. Allred, a Democrat and a native of Bowie, Texas, who lived early in his career in Wichita Falls.[43] The United States Postal Service operates the Wichita Falls Post Office, the Morningside Post Office, the Bridge Creek Post Office, and the Sheppard Air Force Base Post Office.[44]

Education

Wichita Falls is home to Midwestern State University, an accredited four-year college and the only independent liberal arts college in Texas offering both bachelor's and master's degrees. A local branch of nearby Vernon College offers two-year degrees, certificate programs, and workforce development programs, and also Wayland Baptist University, offering both bachelor's and master's degrees, whose main branch is located in Plainview, Texas.

Primary and secondary schools

Public primary and secondary education is covered by the Wichita Falls Independent School District, and the City View Independent School District. The several parochial schools include Notre Dame Catholic school. Other private schools operate in the city, as does an active home-school community. Many of the local elementary schools participate in the Head Start program for preschool-aged children.

Two schools in the Wichita Falls ISD participate in the International Baccalaureate programs. Hirschi High School offers the IB Diploma Programme, and G.H. Kirby Junior High School for the Middle Years Programme. Other public high schools are Wichita Falls High School and S. H. Rider High School (Wichita Falls ISD) and City View High School (City View ISD).

By 1879 the first school was established. The first public school was a log cabin structure established in the 1880s; in 1885 it was replaced with a former courthouse. Wichita Falls High School opened in 1890. That year a school district was created, but problems with the law allowing its establishment meant it was dissolved in 1894 and the city provided schooling until the second establishment of a school district in 1900. In 1908 the Texas Legislature issued a charter for WFISD.[45]

Transportation

Highways

Wichita Falls is the western terminus for Interstate 44. U.S. Highways leading to or through Wichita Falls include 287, 277, 281, and 82. State Highway 240 ends at Wichita Falls and State Highway 79 runs through it. Wichita Falls has one of the largest freeway mileages for a city of its size as a result of a 1954 bond issue approved by city and county voters to purchase rights-of-way for several expressway routes through the city and county, the first of which was opened in 1958 as an alignment of U.S. 287 from Eighth Street at Broad and Holliday Streets northwestward across the Wichita River and bisecting Lucy and Scotland Parks to the Old Iowa Park Road, the original U.S. 287 alignment. That was followed by other expressway links including U.S. 82–287 east to Henrietta (completed in 1968), U.S. 281 south toward Jacksboro (completed 1969), U.S. 287 northwest to Iowa Park and Electra (opened 1962), Interstate 44 north to Burkburnett and the Red River (opened 1964), and Interstate 44 from Old Iowa Park Road to U.S. 287/Spur 325 interchange on the city's north side along with Spur 325 from I-44/U.S. 287 to the main gate of Sheppard Air Force Base (both completed as a single project in 1960). However, cross-country traffic for many years had to contend with several ground-level intersections and traffic lights over Holliday and Broad Streets near the downtown area for about 13 blocks between connecting expressway links until a new elevated freeway running overhead was completed in 2001.

Efforts to create an additional freeway along the path of Kell Boulevard for U.S. 82–277 began in 1967 with the acquisition of right-of-way that included a former railroad right-of-way and the first project including construction of the present frontage roads completed in 1977, followed by freeway lanes, overpasses, and on/off ramps in 1989 from just east of Brook Avenue west to Kemp Boulevard; similar projects west from Kemp to Barnett Road in 2001 followed by Barnett Road west past FM 369 in 2010 to tie in which a project now underway to transform U.S. 277 into a continuous four-lane expressway between Wichita Falls and Abilene.[46]

Public transportation

Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service to other locations served by Greyhound via its new terminal at the Wichita Falls Travel Center located at Fourth and Scott in downtown.[47] Skylark Van Service shuttles passengers to and from Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport on several runs during the day all week long.[48]

The Wichita Falls Municipal Airport is served by American Eagle, with four flights daily to the Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. The Kickapoo Downtown Airport and the Wichita Valley Airport serve smaller, private planes.

Landmarks

- Newby-McMahon Building, c. 1919, also known as the "Worlds Littlest Skyscraper"

- Sacred Heart Catholic Church

_Wichita_Falls.jpg) Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd, 1915

Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd, 1915- Railroad exhibit at Depot Square

_Wichita_Falls.jpg) The Wichita Falls City Hall occupies the bottom floor of the Memorial Auditorium, 1927

The Wichita Falls City Hall occupies the bottom floor of the Memorial Auditorium, 1927

Notable people

- Chase Anderson, professional baseball player

- Greg Abbott, 48th Governor of Texas, first term began January 20, 2015

- JT Barrett, quarterback for Ohio State University, graduated from Rider in 2013

- Ryan Brasier, baseball player

- Joseph Sterling Bridwell, oilman, rancher, conservationist, philanthropist[49]

- John Bundy, magician

- Raymond Carroll, renowned statistician now at Texas A&M University

- Frank Kell Cahoon, Midland oilman and member of Texas House of Representatives; grandson of Frank Kell

- Greyson Chance, singer-songwriter and pianist

- Don Cherry, charting pop singer and leading amateur golfer of 1950s and early '60s

- Bert Clark, football coach, former head coach at Washington State University

- Phyllis Coates, film and television actress who originated role of Lois Lane in first 26 episodes of Adventures of Superman

- William C. Conner (1920–2009), federal judge for United States District Court for the Southern District of New York[50]

- Nic Endo, singer for digital-hardcore band Atari Teenage Riot

- Paul Eggers, Republican nominee for Governor of Texas in 1968 and 1970

- "Cowboy" Morgan Evans, rodeo champion

- John Edward Williams, Author of the novel Stoner.

- Sally Gary, speaker and author

- Mia Hamm, NCAA, World Cup, and Olympic champion soccer player, attended Notre Dame Catholic School in Wichita Falls

- Roberta Haynes, actress

- Eddie Hill, drag racer

- Frank N. Ikard, U.S. representative from Texas' 13th congressional district from 1951 to 1961; oil industry lobbyist

- Robert Jeffress, Baptist clergyman

- Neel Kearby, World War II US Army Air Forces flying ace and Medal of Honor recipient

- Keith Lee, Professional Wrestler

- Khari Long, professional football player

- Rosie Manning, professional football player

- Markelle Martin, professional football player

- Ed Neal, professional football player

- David Nelson, professional football player

- Shaunie O'Neal reality star

- Don Owen, Louisiana news anchor and politician from Shreveport, Louisiana, got his start at KFDX-TV in Wichita Falls in 1953.[51]

- Graham B. Purcell, Jr., Democrat, U.S. representative 1962–1973; post office on Lamar Street in downtown Wichita Falls is named in his honor

- Frances Reid, soap opera actress

- Mark Rippetoe, physical trainer and author, competitive powerlifter, gym owner

- Herbert Rogers, classical pianist

- Lloyd Ruby, race car driver

- Bernard Scott, professional football player

- Frank Lee Sprague, composer and musician

- Keith Stegall, country music artist and record producer

- Rex Tillerson, 69th United States Secretary of State, former ExxonMobil CEO

- John Tower, U.S. Senator from 1961 to 1984

- Tommy Tune, actor, dancer, choreographer and producer, 10-time Tony Award winner

- Nathan Vasher, professional football player

- Ronnie Williams, professional football player

- Dave Willis, voice actor, screenwriter, television producer

- James Huling, reality TV star

See also

- List of museums in Wichita Falls, Texas

- Geology of Wichita Falls, Texas

Notes

- The previous record was 79 in 1980; a 52-day stretch, June 22 to August 12, of uninterrupted 100°F highs, and 100-day stretch, May 27 to September 3, of interrupted 90°F highs occurred. In addition, the all-time warm daily minimum of 88 °F (31 °C) was set on July 26, and June, July, and August of that year were all the hottest on record.[23]

References

- "Wichita Falls mayor speaks to Wichita County Republican Women". Wichita Falls. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Wichita Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Wichita Falls History". WichitaFallsTexas.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- Richard Carter (November 29, 2005). "Full circle: residences, businesses returning to spot where Wichita Falls began". Wichita Falls Times Record News. Wichita Falls, Texas: E. W. Scripps Company. p. A1. ISSN 0895-6138. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

They say business and people have been moving westward in Wichita Falls ever since the city was born on Sept. 27, 1872. The birthplace of the city-the corner of Seventh and Ohio Streets, where the original town lot sale was held – is once again blossoming with renovated apartment buildings, new businesses and increased traffic.

- Bill Whitaker (August 20, 1998). "Cowboys Mosey On, But Littlest Skyscraper Remains". Abilene Reporter-News. Abilene, Texas: E. W. Scripps Company. ISSN 0199-3267. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

But when the building was done, investors discovered the skyscraper was only 30 feet tall, 18 feet deep and 10 feet wide. And of the reportedly $200,000 sunk into the skyscraper's construction – well, that was plainly gone with the wind.

- Carlton Stowers (July 2008). "Legend of the World's Littlest Skyscraper" (PDF). Texas Co-Op Power. Austin, Texas: Texas Electric Cooperatives. 65 (1): 25. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- Le Templar (March 19, 1999). "Historic District Could Expand". Wichita Falls Times Record News. Wichita Falls, Texas: E. W. Scripps Company. p. A1. ISSN 0895-6138. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

The Wichita Falls Landmark Commission wants to more than double the size of the downtown historic district in an effort to slow the loss of buildings that proclaim the city's heritage. Commission members voted unanimously Thursday for expanding the district to include a total of 77 buildings on Indiana and Ohio streets.

- "Brian Hart, "Joseph Alexander Kemp"". Texas State Historical Association online. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- "Kell, Frank". The Handbook of Texas. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- "WICHITA RIVER", Handbook of Texas Online, accessed April 12, 2013. Published by the Texas State Historical Association. See also: Assessment of Channel Changes, Models of Historical Floods and Effects of Backwater on Flood Stage, and Flood Mitigation Alternatives for the Wichita River at Wichita Falls, Texas United States Geological Survey

- "Who We Are".

- "Wichita Falls, TX Tornadoes (1900-Present)". National Weather Service Norman, Oklahoma. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- "Wichita Falls Tornado (1964)". Texas Archive of the Moving Image. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (1993). Significant tornadoes, 1680-1991: A Chronology an Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vt.: Environmental Films. p. 1050. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- "Synopsis and Discussion of the 10 April 1979 Tornado Outbreak". National Weather Service Norman, Oklahoma. January 19, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- "The Great Plains Tornado Outbreak of May 3-4, 1999". National Weather Service Norman, Oklahoma. November 20, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- "Geographic Comparison Table- Texas". American Fast Facts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- LiveScience. Accessed 2014-05-06

- "National Weather Service Climate". Nws.noaa.gov. July 21, 2006. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- Washington Post (26 May 2015). "After massive storms in Oklahoma and Texas, at least nine killed and 30 people missing".

- "Station Name: TX WICHITA FALLS MUNI AP". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 2014-05-05.

- "Monthly Averages for Wichita Falls, Texas". Weather.com. 2011. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- "Texas Almanac: City Population History 1850–2000" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- "Fact Sheet- Wichita Falls city, Texas". American Fast Facts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- Vitro

- James V. Allred Unit (Prison)

- "Local Television Market Universe Estimates" (PDF). Nielsen Media Research. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- "RADIO MARKET SURVEY POPULATION, RANKINGS & INFORMATION: FALL 2016" (PDF). Nielsen Media Research. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- "Lake Wichita Park". wichitafallstx.gov. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- "Wichita Reservoir". tpwd.state.tx.us. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- "Texas Panhandle Plains". texassportfishing.com. Retrieved April 17, 2013.

- "Hotter'N Hell". Hotter'N Hell. Retrieved 2019-02-04.

- Chris Koettler (August 26, 2014). "Wichita Falls Nighthawks Officially Join IFL – Indoor Football League [VIDEO]". www.newstalk1290.com. Townsquare Media EEO. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- "Buss: Minor league baseball a long shot for Wichita Falls". Pecos League. June 25, 2015.

- "Mayors of Wichita Falls". City of Wichita Falls. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- "Mayor". City of Wichita Falls. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016.

- ""Allred Unit". Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- "Post Office Locations in the WICHITA FALLS, TX area". The United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on October 4, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- Sweeten-Shults, Lana (2016-03-14). "Tearing down history?: Alamo and Holland schools". Times Record News. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- Texas), Texas Department of Transportation (State of. "US 277 Expansion". www.txdot.gov. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- "Clarence W. Muehlberger Travel Center | Wichita Falls, TX - Official Website". www.wichitafallstx.gov. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- "Skylark Taxi". www.goskylark.com. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- "Jack O. Loftin, "Joseph Sterling Bridwell"". Texas State Historical Association online. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- Douglas, Martin (July 19, 2009). "William C. Conner, 89, Judge Known for First Amendment Rulings, Dies – Obituary". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- "Carolyn Roy, "Longtime KSLA anchor and news director Don Owen passes away"". KSLA-TV. Retrieved July 2, 2012.