Lubbock, Texas

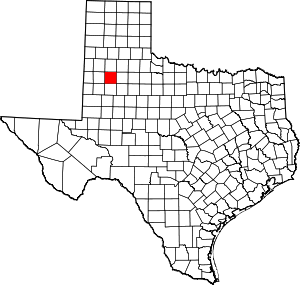

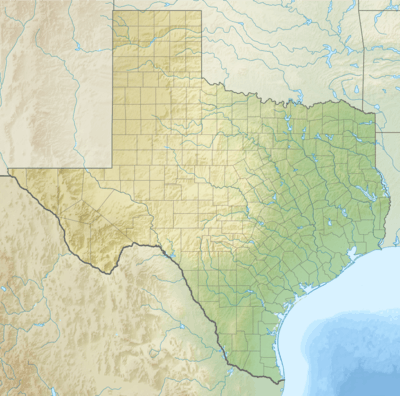

Lubbock (/ˈlʌbək/ LUB-ək)[6] is the 11th-most populous city in the U.S. state of Texas and the county seat of Lubbock County. With a population of 258,862 in 2019, the city is also the 84th-most populous in the United States.[2][7] The city is in the northwestern part of the state, a region known historically and geographically as the Llano Estacado, and ecologically is part of the southern end of the High Plains, lying at the economic center of the Lubbock metropolitan area, which has a projected 2020 population of 327,424.[8]

Lubbock, Texas | |

|---|---|

Downtown | |

Flag Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "Hub City" | |

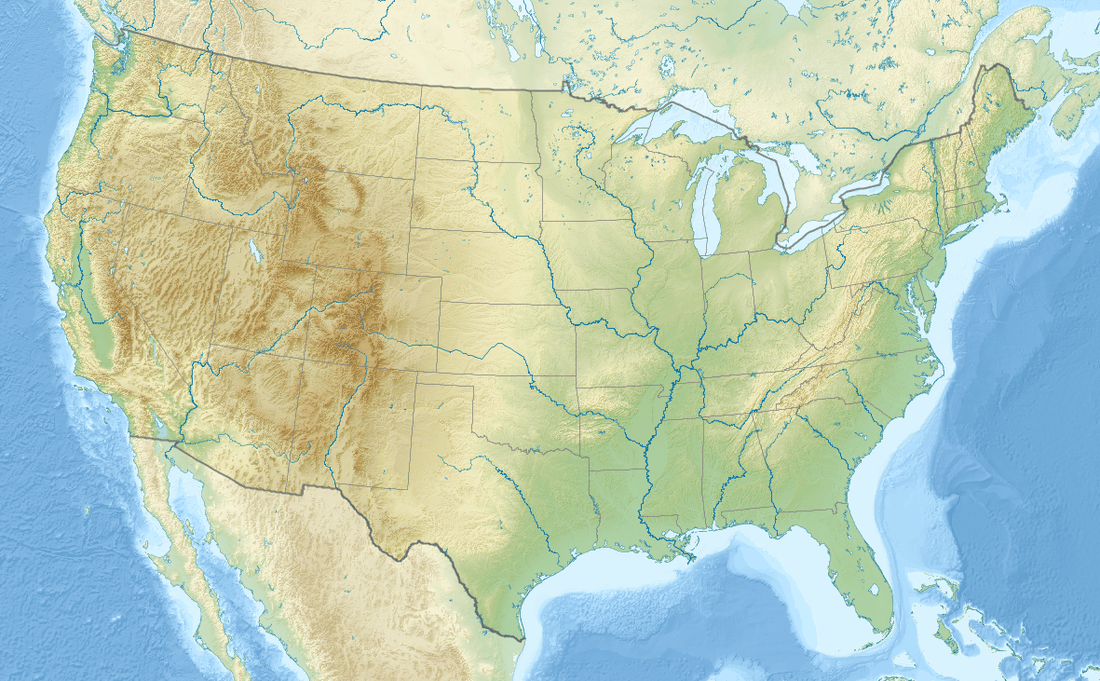

Lubbock Location within Texas  Lubbock Location within the United States  Lubbock Location within North America | |

| Coordinates: 33°34′40″N 101°53′24″W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Lubbock |

| Settled | 1890 |

| Incorporated | March 16, 1909 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Dan Pope (R) |

| • City Council | Juan A. Chadis Shelia Patterson Harris Jeff Griffith Steve Massengale Randy Christian Latrelle Joy |

| • City manager | W. Jarrett Atkinson |

| Area | |

| • City | 123.6 sq mi (320.0 km2) |

| • Land | 122.41 sq mi (317.04 km2) |

| • Water | 1.14 sq mi (2.96 km2) |

| Elevation | 3,202 ft (976 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 258,862 (81st) |

| • Metro | 314,840 |

| • CSA | 338,115 |

| Demonym(s) | Lubbockite |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 79401-79416, 79423, 79424, 79430, 79452, 79453, 79457, 79464, 79490, 79491, 79493, 79499 |

| Area code | 806 |

| FIPS code | 48-45000[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1374760[1] |

| Interstates | |

| U.S. Routes | |

| Website | www |

Lubbock's nickname, "Hub City", derives from it being the economic, educational, and health-care hub of the multicounty region, north of the Permian Basin and south of the Texas Panhandle, commonly called the South Plains.[9] The area is the largest contiguous cotton-growing region in the world[10][11] and is heavily dependent on water from the Ogallala Aquifer for irrigation. CNNMoney.com selected Lubbock as the 12th-best place to start a small business.[12] CNN mentioned the city's traditional business atmosphere: low rent for commercial space, central location, and cooperative city government. Lubbock is home to Texas Tech University, the sixth-largest college by enrollment in the state. Lubbock High School has been recognized for three consecutive years by Newsweek as one of the top high schools in the United States, based in part on its international baccalaureate program.[13]

History

As of 1867, the land that would become Lubbock was the heart of Comancheria, the shifting domain controlled by the Comanche.[14]

Lubbock County was founded in 1876. It was named after Thomas Saltus Lubbock, former Texas Ranger and brother of Francis Lubbock, governor of Texas during the Civil War.[15] As early as 1884, a U.S. post office existed in Yellow House Canyon. A small town, known as Old Lubbock, Lubbock, or North Town, was established about three miles to the east. In 1890, the original Lubbock merged with Monterey, another small town south of the canyon. The new town adopted the Lubbock name. The merger included moving the original Lubbock's Nicolett Hotel across the canyon on rollers to the new townsite. Lubbock became the county seat in 1891,[16] and was incorporated on March 16, 1909. In the same year, the first railroad train arrived.

Texas Technological College (now Texas Tech University) was founded in Lubbock in 1923. A separate university, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, opened as Texas Tech University School of Medicine in 1969. Both universities are now overseen by the Texas Tech University System, after it was established in 1996 and based in Lubbock. Lubbock Christian University, founded in 1957, and Sunset International Bible Institute, both affiliated with the Churches of Christ, have their main campuses in the city. South Plains College and Wayland Baptist University operate branch campuses in Lubbock.

At one time, Lubbock was home to Reese Air Force Base, located 6 mi (10 km) west of the city. It was established in August 1941, during the defense build-up prior to World War II (1941-1945), by the United States Department of War and the U.S. Army as Lubbock Army Airfield. It served the old U.S. Army Air Forces, and later the U.S. Air Force (USAF), after reorganization and establishment in 1947. The USAF base's primary mission throughout its existence was pilot training. The base was closed 30 September 1997, after being selected for closure by the Base Realignment and Closure Commission in 1995, and is now a research and business park called Reese Technology Center.

The city is home to the Lubbock Lake Landmark, part of the Museum of Texas Tech University. The landmark is an archaeological and natural-history preserve at the northern edge of the city. It shows evidence of almost 12,000 years of human occupation in the region. The National Ranching Heritage Center, also part of the Museum of Texas Tech University, houses historic ranch-related structures from the region.

During World War II, airmen cadets from the Royal Air Force, flying from their training base at Terrell, Texas, routinely flew to Lubbock on training flights. The town served as a stand-in for the British for Cork, Ireland, which was the same distance from London, England, as Lubbock is from Terrell.

In August 1951, a V-shaped formation of lights was seen over the city. The "Lubbock Lights" series of sightings received national publicity and is regarded as one of the first great "UFO" cases. The sightings were considered credible because they were witnessed by several respected science professors at Texas Technological College and were photographed by a Texas Tech student. The photographs were reprinted nationwide in newspapers and in Life. Project Blue Book, the USAF's official investigation of the UFO mystery, concluded the photographs were not a hoax and showed genuine objects, but dismissed the UFOs as being either "night-flying moths" or a type of bird called a plover reflected in the nighttime glow of Lubbock's new street lights.

In 1960, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Lubbock's population as 128,691 and area as 75.0 sq mi (194 km2).[17]

On May 11, 1970, the Lubbock Tornado struck the city. Twenty-six people died, and damage was estimated at $125 million. The Metro Tower (NTS Building), then known as the Great Plains Life Building, at 274 ft (84 m) in height, is believed to have been the tallest building ever to survive a direct hit from an F5 tornado.[18] Then-mayor Jim Granberry and the Lubbock City Council, which included Granberry's successor as mayor, Morris W. Turner, were charged with directing the rebuilding of downtown Lubbock in the aftermath of the storm.

In August, 1988, tens of thousands of people came to Lubbock, drawn by an apparition of Mary.

In 2009, Lubbock celebrated its centennial. The historians Paul H. Carlson, Donald R. Abbe, and David J. Murrah co-authored Lubbock and the South Plains.

On August 12, 2008, the Lubbock Chamber of Commerce announced they would lead the effort to get enough signatures to have a vote on allowing county-wide packaged alcohol sales.[19] The petition effort was successful and the question was put to the voters. On May 9, 2009, Proposition 1, which expanded the sale of packaged alcohol in Lubbock County, passed by a margin of nearly two to one, with 64.5% in favor. Proposition 2, which legalized the sale of mixed drinks in restaurants county-wide, passed with 69.5% in favor.[20] On September 23, 2009, The Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission issued permits to more than 80 stores in Lubbock.[21] Prior to May 9, 2009, Lubbock County allowed "package" sales of alcohol (sales of bottled liquor from liquor stores), but not "by the drink" sales, except at private establishments such as country clubs. Inside the city limits, the situation was reversed, with restaurants and bars able to serve alcohol, but liquor stores forbidden.

Geography

Lubbock is considered to be the center of the South Plains, and is situated north of the Permian Basin and south of the Texas Panhandle.[22] According to the United States Census Bureau, as of 2010, the city has a total area of 123.55 sq mi (319.99 km2), of which, 122.41 sq mi (317.04 km2) of it (99.07%) are land and 1.14 sq mi (2.95 km2), or (0.93%), is covered by water.[2]

Skyline

The tallest buildings in Lubbock are listed below.[23][24][25][26]

| Rank | Name | Height ft / m |

Floors (Stories) | Year Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NTS Tower | 274/84 | 20 | 1955 |

| 2 | Wells Fargo Building | 209/64 | 15 | 1968 |

| 3 | TTU Media and Communication Building | 208/63 | 12 | 1969 |

| 4 | Overton Hotel | 165/50 | 15 | 2009 |

| 5 | TTU Architecture Building | 158/48 | 10 | 1971 |

| 6 | Citizens Tower | 153/46.5 | 11 | 1963 |

| 7 | Park Tower | 150/46 | 15 | 1968 |

| – | Caprock Hilton Hotel (demolished) | 144/44 | 12 | 1929 |

| 8 | Lubbock County Office Building | 143/44 | 12 | 1940 |

| 9 | Pioneer Hotel | 136/41.5 | 11 | 1926 |

| 10 = | TTU Chitwood Hall | 134/41 | 12 | 1967 |

| 10 = | TTU Coleman Hall | 134/41 | 12 | 1967 |

| 10 = | TTU Weymouth Hall | 134/41 | 12 | 1967 |

| 13 | Lubbock National Bank Building | 134/41 | 10 | 1979 |

| 14 | Covenant Medical Center | 114/34.5 | 10 | 1994 |

| 15 | Mahon Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse | 107/33 | 8 | 1971 |

| 16 | Victory Tower | 96/29 | 8 | 1999 |

Climate

Lubbock has a cool semiarid climate Köppen classification BSk).[27] On average, Lubbock receives 18.69 inches or 475 millimetres of rain[28] and 8.2 inches or 0.21 metres of snow per year.[29]

In 2013, Lubbock was named the "Toughest Weather City"[30] in America according to the Weather Channel.

Summers are hot, with 78 afternoons on average of 90 °F (32.2 °C)+ highs and 7.4 afternoons of 100 °F (37.8 °C)+ highs, although due to the aridity and elevation, temperatures remain above 70 °F (21.1 °C) on only a few mornings. Lubbock is the 10th-windiest city in the US with an average wind speed of 12.4 mph (20.0 km/h; 5.5 m/s).[31] The highest recorded temperature was 114 °F (45.6 °C) on June 27, 1994.[32]

Winter afternoons in Lubbock are typically sunny and mild, but mornings are cold, with temperatures usually dipping below freezing,[32][33] and as the city is in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 7,[34] lows reaching 10 °F or −12.2 °C occur on 2.5 mornings and 5.7 afternoons occur where the temperature fail to rise above freezing. The lowest recorded temperature was −17 °F (−27.2 °C) on February 8, 1933.[32]

Lubbock can experience severe thunderstorms during the spring, and occasionally the summer. The risk of tornadoes and very large hail exists during the spring in particular, as Lubbock sits on the far southwestern edge of Tornado Alley.

| Climate data for Lubbock, Texas (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 87 (31) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

104 (40) |

109 (43) |

114 (46) |

109 (43) |

109 (43) |

105 (41) |

100 (38) |

90 (32) |

83 (28) |

114 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 54.1 (12.3) |

58.9 (14.9) |

66.7 (19.3) |

75.4 (24.1) |

83.8 (28.8) |

90.6 (32.6) |

92.8 (33.8) |

91.3 (32.9) |

84.5 (29.2) |

75.2 (24.0) |

63.6 (17.6) |

54.1 (12.3) |

74.3 (23.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 26.4 (−3.1) |

30.1 (−1.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

45.7 (7.6) |

55.9 (13.3) |

64.2 (17.9) |

67.7 (19.8) |

66.6 (19.2) |

58.8 (14.9) |

47.9 (8.8) |

35.9 (2.2) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

47.0 (8.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) |

−17 (−27) |

−2 (−19) |

18 (−8) |

27 (−3) |

39 (4) |

49 (9) |

43 (6) |

33 (1) |

17 (−8) |

−1 (−18) |

−2 (−19) |

−17 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.65 (17) |

0.75 (19) |

1.10 (28) |

1.41 (36) |

2.30 (58) |

3.04 (77) |

1.91 (49) |

1.91 (49) |

2.51 (64) |

1.93 (49) |

0.85 (22) |

0.76 (19) |

19.12 (486) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.6 (6.6) |

1.6 (4.1) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

— | 0.9 (2.3) |

2.3 (5.8) |

8.2 (21) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.7 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 7.3 | 8.2 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 66.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 6.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 57.9 | 56.7 | 49.7 | 47.2 | 52.8 | 55.7 | 54.5 | 59.4 | 64.3 | 59.3 | 57.7 | 59.5 | 56.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 210.1 | 202.9 | 267.8 | 286.3 | 310.7 | 326.0 | 338.0 | 318.6 | 261.6 | 258.2 | 214.7 | 201.7 | 3,196.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 66 | 66 | 72 | 73 | 72 | 76 | 77 | 77 | 71 | 73 | 69 | 65 | 72 |

| Source: NOAA (extremes 1911–present, sun and relative humidity 1961–1990)[35][36][37] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 1,938 | — | |

| 1920 | 4,051 | 109.0% | |

| 1930 | 20,520 | 406.5% | |

| 1940 | 31,853 | 55.2% | |

| 1950 | 71,747 | 125.2% | |

| 1960 | 128,691 | 79.4% | |

| 1970 | 149,101 | 15.9% | |

| 1980 | 173,979 | 16.7% | |

| 1990 | 186,206 | 7.0% | |

| 2000 | 199,564 | 7.2% | |

| 2010 | 229,573 | 15.0% | |

| Est. 2019 | 258,862 | [38] | 12.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[39] | |||

As of the census[40] of 2010, 229,573 people, 88,506 households, and 53,042 families resided in the city. The population density was 1,875.6 people per square mile (724.2/km2). The 95,926 housing units averaged 783.7 per square mile (302.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 75.8% White, 8.6% African American, 0.7% Native American, 2.4% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 9.9% from other races, and 2.5% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 32.1% of the population. Non-Hispanic Whites were 55.7% of the population in 2010, down from 77.2% in 1970.[17]

Of the 88,506 households, 31.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.9% were married couples living together, 14.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.1 were not families. About 28.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.09.

In the city, the population was distributed as 23.5% under the age of 18, 18.9% from 18 to 24, 25.8% from 25 to 44, 20.9% from 45 to 64, and 10.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29.2 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.5 males.

In 2011, the estimated median income for a household in the city was $43,364, and for a family was $59,185. Male full-time workers had a median income of $40,445 versus $30,845 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,092. About 11.4% of families and 20.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 24.5% of those under age 18 and 7.3% of those age 65 or over.[41]

2000 census

As of the census[5] of 2000, 199,564 people, 77,527 households, and 48,531 families resided in the city. The population density was 1,738.2 people per square mile (671.1/km2). The 84,066 housing units averaged 732.2/sq mi (282.7/km2). The city's racial makeup was 72.9% White, 8.7% African American, 0.6% Native American, 1.5% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander, 14.3% from other races, and 2.0% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 27.5% of the population.

Of the 77,527 households, 30.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.6% were married couples living together, 12.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.4% were not families. About 28.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 3.07.

The city's population was distributed as 24.9% under the age of 18, 17.9% from 18 to 24, 27.6% from 25 to 44, 18.4% from 45 to 64, and 11.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.1 males.

The city's median household income was $31,844, and for the median family income was $41,418. Males had a median income of $30,222 versus $21,708 for females. The city's per capita income was $17,511. About 12.0% of families and 18.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.9% of those under age 18 and 10.1% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

The Lubbock area is the largest contiguous cotton-growing region in the world and is heavily dependent on federal government agricultural subsidies and on irrigation water drawn from the Ogallala Aquifer. The aquifer is being depleted at a rate unsustainable over the long term. Much progress has been made toward water conservation, and new technologies such as low-energy precision application irrigation were originally developed in the Lubbock area. A new pipeline from Lake Alan Henry is expected to supply up to 3.2 billion US gallons (12,000,000 m3; 12 GL) of water per year.[42]

Adolph R. Hanslik, who died in 2007 at the age of 90, was called the "dean" of the Lubbock cotton industry, having worked for years to promote the export trade. Hanslik was also the largest contributor (through 2006) to the Texas Tech University Medical Center.[43] He also endowed the Texas Czech Heritage and Cultural Center's capital campaign for construction of a new library museum archives building in La Grange in Fayette County in his native southeastern Texas.[44]

The 10 largest employers in terms of the number of employees are Texas Tech University, Covenant Health System, Lubbock Independent School District, University Medical Center, United Supermarkets, City of Lubbock, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, AT&T, and Lubbock County. A study conducted by a professor at the Rawls College of Business determined Texas Tech students, faculty, and staff contribute about $1.5 billion to the economy, with about $297.5 million from student shopping alone.[45]

Lubbock has one regional enclosed mall, South Plains Mall, and many open-air shopping centers, most on the city's booming southwestern side. Lubbock is also home to furniture retailers, such as Spears Furniture, which has been in Lubbock since 1950. Lubbock's newest open-air shopping center is Canyon West at the intersection of Milwaukee Avenue and Marsha Sharp Freeway.

As of 2014, a new shopping center on West Loop 289 began development, including the opening of two anchor stores, Cabela's in 2014 and Costco in 2013.

Economic development

Founded as Market Lubbock in 1997, the city created the Lubbock Economic Development Alliance to recruit new business and industry to Lubbock and to retain existing companies. Its mission is to promote economic growth through the creation of high-quality jobs, attract new capital investment, retain and expand existing businesses, and improve Lubbock's quality of life.

Environmental issues

The Scrub-A-Dubb Barrel Company, in the north of the city, had been the cause of public complaints, and committed numerous environmental violations, since the 1970s.[46] Local KCBD News undertook several investigations into the barrel recycling company's waste-handling practices, and when the business closed in 2011, the Environmental Protection Agency was called in to begin cleaning up the site, which they described as "a threat to public health, welfare, and the environment".[47] Greg Fife, the EPA's on-site coordinator, said: "Out of the 60,000 [barrels] we have on site, we think there are between 2,000 and 4,000 that have significant hazardous waste in them". Local residents were informed, "hazardous substances have overflowed the vats and flowed off the site into nearby Blackwater Draw and subsequently through Mackenzie recreational park. The runoff is easily accessible to children at play in the park, golfers, and the park's wildlife." Remediation of the site was expected to take at least five months, at a cost of $3.5 million in federal dollars.[48]

Arts and culture

Annual cultural events

Every year on July 4, Lubbock hosts the 4th on Broadway event, an Independence Day festival. The event is free to the public, and is considered the largest free festival in Texas. The day's activities usually include a morning parade, a street fair along Broadway Avenue with food stalls and live bands, the Early Settlers' Luncheon, and an evening concert/fireworks program. Broadway Festivals Inc., the nonprofit corporation which organizes the event, estimated a 2004 attendance over 175,000 people. Additionally, the College Baseball Foundation holds events relating to its National College Baseball Hall of Fame during the 4th on Broadway event.

The South Plains Fair is also hosted annually, and features a wide variety of entertainment, including live music, theme-park rides, and various food items sold in an carnival-like setting. During the fair, many agricultural and livestock contests also take place, bringing many participants from the surrounding cities.

The National Cowboy Symposium and Celebration, an annual event celebrating the prototypical Old West cowboy, takes place in Lubbock. The event, held in September, features art, music, cowboy poetry, stories, and the presentation of scholarly papers on cowboy culture and the history of the American West. A chuckwagon cook-off and horse parade also take place during the event.

Music

The West Texas arts scene has created a "West Texas Walk of Fame" within Buddy and Maria Elena Holly Plaza in the historic Depot District, which details musicians such as Buddy Holly, who came from the local area. Lubbock continues to play host to rising and established alt-country acts at venues such as the Cactus Theater and The Blue Light Live, both on Buddy Holly Avenue.[49] The spirit of Buddy Holly is preserved in the Buddy Holly Center in Lubbock's Depot District. The 2004 film Lubbock Lights showcased much of the music associated with the city of Lubbock.

Lubbock is the birthplace of rock and roll legend Buddy Holly, and features a cultural center named for him. The city renamed its annual Buddy Holly Music Festival the Lubbock Music Festival after Holly's widow increased usage fees for his name. Similarly, the city renamed the Buddy Holly West Texas Walk of Fame to honor area musicians as the West Texas Hall of Fame.[50] On January 26, 2009, the City of Lubbock agreed to pay Holly's widow $20,000 for the next 20 years to maintain the name of the Buddy Holly Center. Additionally, land near the center will be named the Buddy and Maria Holly Plaza.[51] Holly's legacy is also remembered through the work of deejays, such as Jerry "Bo" Coleman, Bud Andrews, and Virgil Johnson on radio station KDAV.[52]

Groundbreaking was held on April 20, 2017, for the construction of a new performing arts center, the Buddy Holly Hall of Performing Arts and Sciences, a downtown $153 million project expected to be completed in 2020.[53] Holly Hall will also have concession sites and a bistro with both outdoor and indoor dining. United Supermarkets has been named the food and beverage provider. Thus far, the private group, the Lubbock Entertainment and Performing Arts Association, has raised or received pledges in the amount of $93 million. The Lubbock Independent School District and Ballet Lubbock also support the project.[54]

Lubbock is the birthplace of Morris Mac Davis (born January 21, 1942), who graduated at the age of 16 from Lubbock High School and became a country music singer, songwriter, and actor with crossover success. His early work writing for Elvis Presley produced the hits "Memories", "In the Ghetto", and "A Little Less Conversation". A subsequent solo career in the 1970s produced hits, such as "Baby, Don't Get Hooked on Me", making him a well-known name in popular music. He also starred in his own variety show, a Broadway musical, and various films and television programs.[55]

Outsider musician and psychobilly pioneer The Legendary Stardust Cowboy was also born in Lubbock.[56] He began his musical career there, playing free shows in various parking lots around town.[57] Since striking it big, however, he has not performed in Lubbock, due to how little support and encouragement the city showed him when he was first starting out.[57] John Denver got his start in Lubbock and as a freshman student at Texas Tech in 1966 could be found playing in the Student Union for free. His father was a colonel in the USAF stationed at Reese Air Force Base west of the city.

The Lubbock Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1946 and performs at the Lubbock Memorial Civic Center Theatre.

The Moonlight Musicals Amphitheater is a 930-seat amphitheater opened in 2006. For a period was known as the Wells Fargo Amphitheater. It is used for concerts, stage shows and other special events.

Tourism

Lubbock's Memorial Civic Center hosts many events. Former Mayor Morris Turner (1931–2008), who served from 1972 to 1974, has been called the father of the Civic Center. Other past mayors include Jim Granberry and Roy Bass.

According to a study released by the nonpartisan Bay Area Center for Voting Research, Lubbock is the second-most conservative city in the United States among municipalities greater than 100,000 in population.[58]

Lubbock sits within the Texas High Plains, an eight-million-acre region that produces 80% of the state's wine grapes.[59] Five wineries, including the most award-winning in Texas (LLano Estacado Winery), are based near Lubbock, providing a significant draw for wine lovers.[60]

The National Ranching Heritage Center, a museum of ranching history, is in Lubbock. It features a number of authentic early Texas ranch buildings, as well as a railroad depot and other historic buildings. An extensive collection of weapons is also on display. Jim Humphreys, late manager of the Pitchfork Ranch east of Lubbock, was a prominent board member of the center. The American Cowboy Culture Association, founded in 1989, is in Lubbock; it co-hosts the annual National Cowboy Symposium and Celebration held annually from Thursday through Sunday after Labor Day.[61]

The Southwest Collection, an archive of the history of the region and its surroundings, which also works closely with the College Baseball Foundation, is on the campus of Texas Tech University, as are the Moody Planetarium and the Museum of Texas Tech University.

The Depot District, an area of the city dedicated to music and nightlife in the old railroad depot area, boasts theatres, upscale restaurants, and cultural attractions. The district is also home to several shops, pubs, nightclubs, a radio station, a magazine, a winery, a salon, and other establishments. Many of the buildings were remodeled from the original Fort Worth & Denver South Plains Railway Depot which stood on the site. The Buddy Holly Center, a museum highlighting the life and music of Buddy Holly, is also in the Depot District, as is the restored community facility, the Cactus Theater.

Lubbock is also home to the Silent Wings Museum. Located on North I-27, Silent Wings features photographs and artifacts from World War II-era glider pilots.

The Science Spectrum is an interactive museum and IMAX Dome theatre with a special focus on children and youth.

National Register of Historic Places

- Cactus Theater

- Canyon Lakes Archaeological District

- Carlock Building

- Fort Worth and Denver South Plains Railway Depot

- Fred and Annie Snyder House

- Holden Properties Historic District

- Kress Building

- Lubbock High School

- Lubbock Lake Landmark

- Lubbock Post Office and Federal Building

- South Overton Residential Historic District

- Texas Technological College Dairy Barn

- Texas Technological College Historic District

- Tubbs-Carlisle House

- Warren and Myrta Bacon House

- William Curry Holden and Olive Price Holden House

Sports

The Texas Tech Red Raiders are in the Big 12 Conference and field 17 teams in 11 different varsity sports. Men's varsity sports at Texas Tech are baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, tennis, and indoor and outdoor track and field. Women's varsity sports are basketball, cross country, golf, indoor and outdoor track and field, soccer, softball, tennis, and volleyball. The university also offers 30 club sports, including cycling, equestrianism, ice hockey, lacrosse, polo, rodeo, rugby, running, sky diving, swimming, water polo, and wrestling. In 2006, the polo team, composed of Will Tankard, Ross Haislip, Peter Blake, and Tanner Kneese, won the collegiate national championship.[62]

The football program has been competing since October 3, 1925. The Red Raiders have won 11 conference titles and been to 31 bowl games, winning five of the last seven.

The men's basketball program, started in 1925, has been to the NCAA Tournament 18 times—advancing to the Sweet 16 seven times, and the Elite Eight twice, and in 2019 they reached the Final Four and were the NCAA Tournament Runner-Up losing to the Virginia Cavaliers in overtime 77–85. Bob Knight, hall-of-famer and second-winningest coach in men's college basketball history, coached the team from 2001 to 2008.

Of the varsity sports, Texas Tech has had its greatest success in women's basketball. Led by Sheryl Swoopes and head coach Marsha Sharp, the Lady Raiders won the NCAA Women's Basketball Championship in 1993. The Lady Raiders have also been to the NCAA Elite Eight three times and the NCAA Sweet 16 seven times. In early 2006, Lady Raiders coach Marsha Sharp resigned and was replaced on March 30, 2006 by Kristy Curry, who had been coaching at Purdue.

In addition, Lubbock is the home of the Chaparrals of Lubbock Christian University. With a recent move up to NCAA Division 2, the women's basketball team has won the 2016 and 2019 national championships.[63] In 2009, the Lubbock Christian University[64] baseball team won their second NAIA National Championship.

In 2007, the Lubbock Renegades began play as a member of the af2, a developmental league of the Arena Football League. The team discontinued operation in 2008.

High-school athletics also feature prominently in the local culture.

Little League

In 2007, the Lubbock Western All-Stars Little League Baseball team made it to the final four of the Little League World Series.[65]

Parks and recreation

In March 1877, during the Buffalo Hunters' War, the Battle of Yellow House Canyon took place at what is now the site of Mackenzie Park. Today, Mackenzie Park is home to Joyland Amusement Park, Prairie Dog Town, and both a disc golf and a regular golf course. The park also holds the American Wind Power Center, which houses over 100 historic windmills on 28 acres (11 hectares). Two tributaries of the Brazos River wind through Mackenzie Park, which is collectively part of the rather extensive Lubbock Park system.[66][67] These two streams, Yellow House Draw and Blackwater Draw, converge in the golf course, forming the head of Yellow House Canyon, which carries the waters of the North Fork Double Mountain Fork Brazos River.[68]

Lubbock is home to numerous parks, scattered throughout the city. Most parks feature a small lake and attract waterfowl of various species. One of Lubbock's larger lakes, Dunbar Historic Lake, lies in Dunbar Historic Lake Park, near Mackenzie Park. Drainage exits into the North Fork Double Mountain Fork Brazos River. The park features miles of hiking trails and the Crosbyton-Southplains Railroad trestle, built in 1911, which spans the North Fork Double Mountain Fork Brazos River at the park's southeast end. This trestle has become known by many locals as "Hell's Gate" or "Hell's Gate Trestle" for its supposed paranormal activity.

Government

Municipal government

| Mayor | Dan Pope (R) |

| District 1 | Juan A. Chadis |

| District 2 | Shelia Patterson Harris |

| District 3 | Jeff Griffith |

| District 4 | Steve Massengale |

| District 5 | Karen Gibson |

| District 6 | Latrelle Joy (Mayor Pro Tem) |

Lubbock has a council-manager government system, with all governmental powers resting in a legislative body called a city council.[70] Voters elect six council members, one for each of Lubbock's six districts, and a mayor.[70] The council members serve for a term of four years, and the mayor serves for two years.[70] After the first meeting of the city council after newly elected council members are seated, the council elects a mayor pro tempore, who serves as mayor in absence of the elected mayor.[70] The council also appoints a city manager to handle the ordinary business of the city.[70] Currently, no term limits are set for either city council members or the mayor.

The Lubbock Police Department was shaped by the long-term administration of Chief J. T. Alley (1923–2009), who served from 1957 to 1983, the third-longest tenure in state history. Under Chief Alley, the department acquired its first Juvenile Division, K-9 Corps, Rape Crisis Center, and Special Weapons and Tactics teams. He also presided over the desegregation of the department and coordinated efforts during the 1970 tornadoes.[71] As of 2015, the department had 403 officers.[72]

Education

Schools

Schools in Lubbock are operated by several public school districts and independent organizations.

Public schools:

- Lubbock Independent School District

- Frenship Independent School District

- Lubbock-Cooper Independent School District

- Roosevelt Independent School District

Private schools:

- All Saints Episcopal School

- Christ the King Cathedral School

- Trinity Christian School

- Lubbock Christian School

- Kingdom Preparatory Academy

- Southcrest Christian School

Charter schools: Harmony Science Academy, Sharp Academy

Higher education

Lubbock is home to Texas Tech University, which was established on February 10, 1923, as Texas Technological College. It is the leading institution of the Texas Tech University System and has the seventh-largest enrollment in the state of Texas. It is one of two schools (the other being UT Austin) in Texas to house an undergraduate institution, law school, and medical school at the same location. Altogether, the university has educated students from all 50 US states and over 100 foreign countries. Enrollment has continued to increase in recent years, and growth is on track with a plan to have 40,000 students by 2020.

Lubbock is also home to other college campuses in the city, including Lubbock Christian University, South Plains College, Wayland Baptist University, Virginia College, Kaplan College, and Sunset International Bible Institute.

Covenant Health System, a health-care provider serving West Texas and Eastern New Mexico, operates a school of nursing, school of radiography, and school of surgical technology.

Media

Lubbock's main newspaper is the daily Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, which is owned by Morris Communications. The newspaper also publishes a full-color lifestyle magazine, Lubbock Magazine,[73] eight times a year. Texas Tech University publishes a student-run daily newspaper called The Daily Toreador.

Local TV stations include KTTZ-TV-5 (PBS), KCBD-11 (NBC), KLBK-13 (CBS), KAMC-28 (ABC), and KJTV-TV-34 (Fox).

Texas Tech University Press, the book- and journal-publishing office of Texas Tech University, was founded in 1971, and as of 2012, has about 400 scholarly, regional, literary, and children's titles in print.

Infrastructure

The Texas Department of Criminal Justice operates the Lubbock District Parole Office in Lubbock.[74]

The Texas Department of Transportation operates the West Regional Support Center and Lubbock District Office in Lubbock.[75][76]

The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Lubbock.

Transportation

Highways

Lubbock is served by major highways. Interstate 27 (the former Avenue H) links the city to Amarillo and Interstate 40, a transcontinental route. I-27 was completed through the city in 1992 (it originally terminated just north of downtown). Other major highways include US 62 and US 82, which run concurrently (except for 4th Street (82) and 19th Street (62)) through the city east–west as the Marsha Sharp Freeway, 19th Street (62 only), 4th Street/Parkway Drive (82 only) and Idalou Highway. US 84 (Avenue Q/Slaton Highway/Clovis Road) is also another east–west route running NW/SE diagonally. US Highway 87 runs between San Angelo and Amarillo and follows I-27 concurrently. State Highway 114 runs east–west, following US 62/82 on the east before going its own way. Lubbock is circled by Loop 289, which suffers from traffic congestion despite being a potential bypass around the city, which is the reason behind I-27 and Brownfield Highway being built through the city to have freeway traffic flow effectively inside the loop.

The city is set up on a simple grid plan. In the heart of the city, numbered streets run east–west and lettered avenues run north–south – the grid begins at Avenue A in the east and First Street in the north. North of First Street, city planners chose to name streets alphabetically from the south to the north after colleges and universities. The north–south avenues run from A to Y. What would be Avenue Z is actually University Avenue, since it runs along the east side of Texas Tech. Beyond that, the A-to-Z convention resumes, using US cities found east of the Mississippi (e.g. Akron Avenue, Boston Avenue, Canton Avenue). Again, the Z name is not used, with Slide Road appearing in its place.

Rail service

Lubbock currently does not provide intercity rail service, although various proposals have been presented over the years to remedy this. One, the Caprock Chief, would have seen daily service as part of a Fort Worth, Texas—Denver, Colorado service, but it failed to gain interest.[77] Lubbock is served by the BNSF Railway company, Plainsman Switching Company (PSC), and West Texas & Lubbock Railway (WTLC). PSC interchanges with BNSF (also with UP through a UP-BNSF Haulage agreement) in Lubbock and has 19 miles of track within city limits of Lubbock with 36 customers. Options exist for transloading a variety of materials on the line, from wind-turbine parts to steel shafts. PSC handles many commodities such as cottonseed, cottonseed oil, cottonseed meal, cottonseed hulls, milo, corn, wheat, pinto beans, sand, rock, lumber, nonperishable food items, chemicals, paper products, brick, and bagging material, and can also store cars. WTLC interchanges with BNSF (also with UP through a UP-BNSF Haulage agreement) in Lubbock. WTLC has a yard on the west side of Lubbock, where they switch cars to go down their line to Levelland or to Brownfield. WTLC handles commodities of grains, chemicals, sands, peanuts, lumber, etc.

Airports

The city's air services are provided by Lubbock Preston Smith International Airport, which is named for the Lubbock businessman who became lieutenant governor and governor of Texas. It is on the city's northeast side. The airport is the eighth-busiest airport in Texas. Lubbock Preston Smith Airport also plays host as a major hub to FedEx's feeder planes that serve cities around Lubbock.

Intercity bus service

Greyhound Lines operates the Lubbock Station at 801 Broadway, just east of the Lubbock County Courthouse.[78]

Public transportation

Public transportation is provided by Citibus, a bus transit system running Monday through Saturday every week with a transit center hub in downtown. It runs bus routes throughout the city, with the main routes converging at the Downtown Transfer Plaza, which also houses the Greyhound bus terminal. Citibus has been in continual service since 1971, when the city of Lubbock took over public transit operations. The paratransit system is called Citiaccess.

Citibus' six diesel-electric hybrid buses have begun service on city routes. Managers hope the buses will use 60% of the fuel their older, larger versions consume in moving customers across the city. The buses seat 23 passengers, can support full-sized wheelchairs, and will run on all but two city-based routes.

Modal characteristics

According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 80.9% of working Lubbock (city) residents commuted by driving alone, 12.9% carpooled, 1% used public transportation, and 1.5% walked. About 1.5% used all other forms of transportation, including taxi, bicycle, and motorcycle. About 2.3% worked at home.[79]

In 2015, 7.3% of Lubbock households were without a car, which decreased to 5.6% in 2016. The national average was 8.7% in 2016. Lubbock averaged 1.74 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8 per household.[80]

Milwaukee Avenue

In the early years of the 21st century, Lubbock turned its Milwaukee Avenue into a major thoroughfare. Previously, Milwaukee was a 4-mile dirt road on farm land with hardly any traffic a mile or more from major development. With growth headed westward, the city allocated nearly $20 million to convert the road into a seven-lane concrete thoroughfare. In 2004, the city funded the project and other developments to come by establishing a new fund that tapped part of the franchise fees received. As of 2018, more than $124 million in street construction has been possible from the fund, including Slide Road, 98th Street, Indiana Avenue, and the last phases of the Marsha Sharp Freeway. Public Works Director Wood Franklin said Milwaukee Avenue was conceived on the "build it and they will come" theory. Marc McDougal, then the mayor of Lubbock, described the project as a well calculated risk that subsequently greatly benefited the city.[81]

Notable people

The city has been the birthplace or home of several musicians, including Buddy Holly,[82] Delbert McClinton,[83] Jimmie Dale Gilmore,[84] Butch Hancock,[85] and Joe Ely[86] (collectively known as The Flatlanders), Mac Davis,[87] Bobby Keys, Terry Allen,[88] Lloyd Maines[89] and his daughter, Dixie Chicks singer Natalie Maines,[90] and indie folk songwriter Kevin Morby.[91]

Texas Tech alumni Jay Boy Adams, Pat Green,[92] Cory Morrow, Wade Bowen, Josh Abbott, and Amanda Shires, and Coronado High School graduate Richie McDonald[93] (lead singer of Lonestar until 2007).

Pete Orta[94] of the Christian rock group Petra, Christian artist Josh Wilson,[95] Norman Carl Odam (aka The Legendary Stardust Cowboy),[96]

Basketball players Craig Ehlo[97] and Daniel Santiago,[98] and football players Ron Reeves and Mason Crosby[90] have also called Lubbock home.

Former MLB pitcher, Greg Minton

Shooting Guard for the Minnesota Timberwolves, Jarrett Culver, was born in Lubbock and went to Coronado High School

Boxers Ruben Castillo,[99] Terry Norris and Orlin Norris[100] were born in Lubbock, as was basketball player and coach Micheal Ray Richardson.[101]

National Motorcycle Champion, Don Wayne (Bubba Shobert) was born and went to school in Lubbock.

Actor Barry Corbin went to Monterey High School and Texas Tech University.

Mark Payne is an American professional basketball player who plays for Champagne Châlons Reims Basket of the LNB Pro A.

The city is also the birthplace of actor Chace Crawford (The Covenant, Gossip Girl),[102]

Singer Travis Garland of the band NLT, musician, writer, composer, singer, producer, and LGBT activist Logan Lynn, artist Joshua Meyer, and political activist William John Cox (Billy Jack Cox)

Public speaker and televangelist Kenneth Copeland was born in Lubbock.[90]

Lubbock is the home of the historians Alwyn Barr,[103] Dan Flores,[104] Allan J. Kuethe,[105] Paul H. Carlson, and Ernest Wallace.[106]

Bidal Aguero, a civil-rights activist in Lubbock, was the publisher of the longest-running Hispanic newspaper in Texas.[107]

Author Micah Wright was born in Lubbock.[90]

Gabor B. Racz, professor of anesthesiology at Texas Tech University Health Science Center, is the inventor of the Racz catheter.[108]

Kevin Williamson, National Review roving correspondent, grew up in Lubbock and once worked for the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal.

Steven Berk, dean of medicine at the Texas Tech Health Science Center and a specialist in infectious diseases, wrote in 2011 Anatomy of a Kidnapping: A Doctor's Story, based on his 4-hour kidnapping in 2005 while he was living in Amarillo.[109]

Lawyer, lexicographer, and teacher Bryan A. Garner was born in Lubbock.[90] J. Michael Bailey, psychologist and professor at Northwestern University, was born in Lubbock.[90] Spencer Wells, a geneticist, grew up in Lubbock and graduated from Lubbock High School.

United States Army officer Taylor Force after whom the Taylor Force Act was named is from Lubbock.

Lubbock's founding mayor was Frank E. Wheelock, who held the office from 1909 to 1915. State Senator William H. Bledsoe in 1923 pushed for the legislation and the first $1 million appropriation which brought Texas Tech University to Lubbock. State Representative Richard M. Chitwood, chairman of the House Education Committee, became the first Texas Tech business manager, but served for only 15 months prior to his death in Dallas in 1926.[110] Representative Roy Alvin Baldwin of Slaton was co-author with Bledsoe of the Texas Tech legislation.[111]

Recent state legislators from Lubbock include State Senators John T. Montford[112] and Robert L. Duncan,[113] former State Representatives Carl Isett,[114] Isett's successor, John Frullo,[115] Ron Givens, the first African-American Republican in the Texas House since 1882,[116] and his predecessor, Delwin Jones, and Jones' successor, Charles Perry.[117] It is the birthplace of the late U.S. Representative Mickey Leland of Houston.[118] W. E. Shattuc, who raced in the Indianapolis 500 in 1925, 1926, and 1927, lived in Lubbock. Preston Earnest Smith, a long-time resident of Lubbock, was the 40th Governor of Texas from 1969 to 1973 and earlier served as the lieutenant governor from 1963 to 1969.[119]

Sister cities

Current sister cities

Former sister cities

Proposed sister cities

References

- "Lubbock". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- "Lubbock (city) QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau". Geographic Identifiers. United States Census Bureau. 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015, Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico". 2015 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. 2016. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". 2015 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. 2016. Archived from the original (CSV) on February 13, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Lubbock". Merriam-Webster Dictionary (Online ed.). Merriam-Webster Incorporated. 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2006. The pronunciation has been newsworthy: Westbrook, Ray (July 25, 2011). "The linguistics of Lubb-uhk: The grating sound of 'Lubbick' hard on the ears of some longtime Lubbockites". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. pp. A1, A5.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Texas Population, 2020 (Projections)". 2020 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "Media Resources". Lubbock Chamber of Commerce. 2006. Archived from the original on May 6, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- "Lubbock Community". Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010.

- Morrow, M. R.; Kreig, D. R. "Cotton Management Strategies for a Short Growing Season Environment: Water-Nitrogen Considerations". Agronomy Journal. Archived from the original on January 14, 2009.

- "Lubbock earns high ranking as place to launch small business". Lubbock Avalanche Journal. October 31, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- "Lubbock High makes Newsweek's top list of high school". Newsweek. 2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- Hamalainnen, Pekka (2009). The Comanche Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 316.

- "Handbook of Texas Online". Texas State Historical Association.

- Paul H. Carlson, "The Nicolett Hotel and the Founding of Lubbock", West Texas Historical Review, Vol. 90 (2014), pp. 8-9, 11.

- "Texas – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- "Lubbock, Texas". National Weather Service Forecast Office. Archived from the original on October 9, 2006.

- "Chamber to Lead Alcohol Petition Effort". My Fox Lubbock. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- "Lubbock County voters approve alcohol sales issues". Lubbock Avalanche Journal. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- "State will clear stores to sell alcohol today". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Retrieved September 23, 2009.

- "About Lubbock". The City of Lubbock. Archived from the original on December 18, 2007. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- Young, Adam D. (August 9, 2010). "City's tallest buildings likely won't face challenge for years". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "Lubbock". SkyscraperPage. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- "High-rise buildings in Lubbock". Emporis. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- "Low-rise buildings in Lubbock". Emporis. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- "Normals Monthly Station Details: LUBBOCK INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, TX US, GHCND:USW00023042 - Climate Data Online (CDO) - National Climatic Data Center (NCDC)". Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- "Lubbock at a Glance". Lubbock Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014.

- "Snowfall – Average Total in Inches". NOAA Climate Services.

- Loesh, Jennifer. "Voters declare Lubbock toughest weather city". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal.

- "Lubbock, Texas – Average Wind Speed By Month and Year". Wind-speed.weatherdb.com. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- "Monthly Averages for Lubbock, TX". The Weather Channel.

- "Facts About Lubbock, TX" (PDF). Texas Tech University. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- "Zone 7". Arborday.org. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- "National Weather Service Climate". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "Station Name: TX LUBBOCK". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "WMO Climate Normals for Lubbock/Regional ARPT, TX 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Lubbock city, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (DP03): Lubbock city, Texas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- Eric Finley (October 9, 2008). "Battle on for water until Alan Henry pipeline done | Lubbock Online | Lubbock Avalanche-Journal". Lubbock Online. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- Ginter, Derrick. "Local Cotton Exporter, Philanthropist Dies". KOHM.

- "Hanslik's contribution to the Texas Czech Center announced". El Campo Leader-News. Archived from the original on October 8, 2008.

- Graham, Mike. "Students' return boosts university's billion-dollar impact in Lubbock". The Daily Toreador. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2008.

- Little, Ann Wyatt (June 12, 2009). "City removes Scrub-A-Dubb land from proposed zoning change". KCBD News. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- "EPA takes charge of hazardous waste site in North Lubbock". Lubbock Local News. August 30, 2011. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- Slother, Michael (August 31, 2011). "EPA takes charge of hazardous waste site in North Lubbock". KCBD News. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- "RockHall inductee Buddy Holly". rockhall.com.

- "Lubbock scraps Holly name at two sites". Yahoo! Music. Retrieved September 6, 2008.

- Graham, Mike (January 29, 2009). "City approves $20k contract for Buddy Holly naming rights". The Daily Toreador. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- "KDAV DJ, Bud Andrews". KDAV. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008.

- "Lubbock's $153M Buddy Holly Hall Due to Open in 2020". www.constructionequipmentguide.com. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- William Kerns. "Restaurant partnership, groundbreaking date announced for Buddy Holly Hall". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- William Kerns (March 2, 2008). "Mac Davis remembers his days in Lubbock | Lubbock Online | Lubbock Avalanche-Journal". Lubbock Online. Archived from the original on August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- Chusid, Irwin. Songs in the Key of Z: The Curious World of Outsider Music. A Capella Books.

- Rob Weiner, Texas Tech University, "West Texas' Unsung Hero: the Legendary Stardust Cowboy", West Texas Historical Association, annual meeting in Fort Worth, Texas, February 27, 2010

- "Study Ranks America's Most Liberal and Conservative Cities". GovPro.

- "Texas Wine Industry Facts". www.txwines.org. Texas Wine & Grape Growers Association. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- "Tour Texas - Lubbock". Tour Texas. Tour Texas.

- "National Cowboy Symposium & Celebration, Inc. (Lubbock, Texas)". cowboy.org. Archived from the original on August 26, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- "2006 Collegiate Polo Championships". The Polo Zone.

- https://lcu.edu/about-lcu/news/article/detail/News/undefeated-lady-chaps-take-national-championship-title-lcu-celebrates/hash/a4cd80d00d1913bd123057412806fd0c/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Home". Lcu.edu. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- "2007 Little League World Series". Little League Baseball. Archived from the original on January 10, 2018.

- "Mackenzie Park/Prairie Dog Town". Texas Travel. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- "Lubbock's Mackenzie Park". Lubbock Hospitality.

- United States Board on Geographical Names. 1964. Decisions on Geographical Names in the United States, Decision list no. 6402, United States Department of the Interior, Washington DC, p. 54.

- "Lubbock City Council". City of Lubbock, Texas. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- "Lubbock City Charter". Archived from the original on September 14, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Elliott Blackburn. "Late police chief saw city through tornado, was known for stern fairness". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Archived from the original on November 2, 2011. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- Villacin, Patricia (July 10, 2015). "Lubbock Police Department welcomes 11 new recruits". KCBD.

- "Lubbock Online | Lubbock Avalanche-Journal". Thelubbockmagazine.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2009. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- Archived September 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived October 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Archived October 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Van Wagenen, Chris (August 2, 2001). "Lubbock officials backing plans for Amtrak rail service". Amarillo Globe-News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- "Greyhound". Greyhound. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- "Means of Transportation to Work by Age". Census Reporter. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- "Car Ownership in U.S. Cities Data and Map". Governing. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Matt Dotray (July 28, 2018). "Leaders say Lubbock's Milwaukee Avenue took creative funding, project of similar scope not foreseen". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Norwine, Doug and Shrum, Gary (2006). Heritage Auction Galleries Presents the Maria Elena Collection of Buddy Holly Memorabilia Auction Catalog. Heritage Capital Corporation. p. 33. ISBN 9781599670515.

- "Delbert McClinton". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Jimmie Dale Gilmore". 2014 Net Industries. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Butch Hancock". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Joe Ely". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Mac Davis". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Terry Allen". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Lloyd Maines". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Lubbock, Texas". City-Data.com. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- cite web|title=Kevin Morby|url=https://www.last.fm/music/Kevin+Morby/+wiki

- "Pat Green". 2014 American Profile, Publishing Group of America. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Richie McDonald". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "Josh Wilson". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Norman Carl Odam". 2014 AllMusic, a division of All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Craig Ehlo". 2000–2014 Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Daniel Santiago". 2000–2014 Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Ruben Castillo". Box Rec. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "Orlin Norris". BoxRec. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Micheal Ray Richardson". 2000–2014 Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Chace Crawford". 2014 CBS Interactive Inc. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Alwyn Barr". The Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Dan Flores". The University of Montana. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Allan J. Kuethe". 2009 Texas Tech University. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Ernest Wallace". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Bidal Aguero's Remarkable Journey". eleditor.com, November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on January 10, 2013. Retrieved April 2, 2010.

- Robin Briscoe (November 5, 2006). "Memories of escape from Hungary still burn bright". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- Billy Hathorn, Review of Anatomy of a Kidnapping: A Doctor's Story by Steven Lee Berk, M.D., Texas Tech University Press, 2011, in West Texas Historical Review, Vol. 89 (2013), pp. 184-186

- "Richard M. Chitwood". Texas Legislative Reference Library. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- "Roy Alvin". Texas Legislative Reference Library. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- "John T. Montford". StateCemetery@tfc.state.tx.us. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Robert L. Duncan". The Senate of Texas. Archived from the original on June 6, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Carl Isett". Texas House of Representatives. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "John Frullo". Texas House of Representatives. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "New Lubbock legislator Givens optimistic about new session: Givens the first black Republican legislator in 103 years", Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, January 7, 1985

- "Charles Perry". Texas House of Representatives. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Mickey Leland". Office of the Historian: history@mail.house.gov Office of Art & Archives, Office of the Clerk: art@mail.house.gov, archives@mail.house.gov. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- "Preston Earnest Smith". National Governors Association. Retrieved June 2, 2014.

- Enrique Rangel (March 3, 2001). "City Council hopes sister city commission pays off". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- Enrique Rangel (December 18, 2008). "Mexican border city wants to be Lubbock's sister city". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

Further reading

- Abbe, Donald R. & Carlson, Paul H. (2008). Historic Lubbock County: An Illustrated History. Historical Pub Network. ISBN 978-1-893619-90-6. An illustrated history of Lubbock

- Pfluger, Marsha (2004). Across Time and Territory: A Walk through the National Ranching Heritage Center. National Ranching Heritage Center. ISBN 978-0-9759360-0-9.

- Bogener, Stephen, and Tydeman, William, editors (2011). Llano Estacado: An Island in the Sky. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-682-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) The world's largest expanse of flat land, in words and images

- Neal, Bill (2009). Sex, Murder, and the Unwritten Law: Courting Judicial Mayhem, Texas Style. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-662-8.

- Cochran, Mike & Lumpkin, John (1999). West Texas: A Portrait of Its People and Their Raw and Wondrous Land. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 978-0-89672-426-6. Anecdotes from the region

- Martin, Conny McDonald (2003). Art Lives in West Texas. Pecan Press. ISBN 978-0-9670928-1-2. The History of the Lubbock Art Association and of art activities in Lubbock and surrounding counties

External links

- Official website

- Visit Lubbock