Tagalog Republic

Tagalog Republic (Filipino: Republika ng Katagalugan or Republikang Tagalog) is a term used to refer to two revolutionary governments involved in the Philippine Revolution against Spain and the Philippine–American War. Both were connected to the Katipunan revolutionary movement.

Etymology

The term Tagalog refers to both an ethno-linguistic group in the Philippines and their language. Katagalugan may refer to the historical Tagalog regions in the large island of Luzon, the northern part of the Philippine Archipelago.

However, the Katipunan secret society extended the meaning of these terms to all natives in the Philippine islands. The society's primer explains its use of Tagalog in a footnote:

| “ | Sa salitáng tagalog katutura’y ang lahát nang tumubo sa Sangkapuluáng itó; sa makatuid, bisaya man, iloko man, kapangpangan man, etc., ay tagalog din.

(The word tagalog means all those born in this archipelago; therefore, though visayan, ilocano, pampango, etc. they are all tagalogs.)[1][2] |

” |

The revolutionary Carlos Ronquillo wrote in his memoirs:

| “ | Ang tagalog o lalong malinaw, ang tawag na "tagalog" ay waláng ibáng kahulugán kundi ‘tagailog’ na sa tuwirang paghuhulo ay taong maibigang manirá sa tabíng ilog, bagay na 'di maikakaila na siyáng talagáng hilig ng tanang anák ng Pilipinas, saa’t saán mang pulo at bayan.

(Tagalog or, stated more clearly, the name "tagalog" has no other meaning but "tagailog" which, traced directly to its root, refers to those who prefer to settle along rivers, truly a trait, it cannot be denied, of all those born in the Philippines, in whatever island or town.)[1][2] |

” |

In this respect, Katagalugan may be translated as the "Tagalog nation."[1][2]

Andrés Bonifacio, a founding member of the Katipunan and later its supreme head (Supremo), promoted the use of Katagalugan for the Philippine nation. The term "Filipino" was then reserved for Spaniards born in the islands. By eschewing "Filipino" and "Filipinas" which had colonial roots, Bonifacio and his cohorts "sought to form a national identity."[1]

In 1896, the Philippine Revolution broke out after the discovery of the Katipunan by the authorities. Prior to the outbreak of hostilities, the Katipunan had become an open revolutionary government.[1][3][4] The American historian John R. M. Taylor, custodian of the Philippine Insurgent Records, wrote:

| “ | The Katipunan came out from the cover of secret designs, threw off the cloak of any other purpose, and stood openly for the independence of the Philippines. Bonifacio turned his lodges into battalions, his grandmasters into captains, and the supreme council of the Katipunan into the insurgent government of the Philippines.[1][2] | ” |

Several Filipino historians concur. According to Gregorio Zaide:

| “ | The Katipunan was more than a secret revolutionary society; it was, withal, a Government. It was the intention of Bonifacio to have the Katipunan govern the whole Philippines after the overthrow of Spanish rule.[1][4] | ” |

Likewise, Renato Constantino and others wrote that the Katipunan served as a shadow government.[5][6][7][8]

Influenced by Freemasonry, the Katipunan had been organized with "its own laws, bureaucratic structure and elective leadership".[1] For each province it involved, the Supreme Council coordinated provincial councils[2] which were in charge of "public administration and military affairs on the supra-municipal or quasi-provincial level"[1] and local councils,[2] in charge of affairs "on the district or barrio level".[1]

Bonifacio

| Sovereign Tagalog Nation Haring Bayang Katagalugan | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1896–1897 | |||||||||||

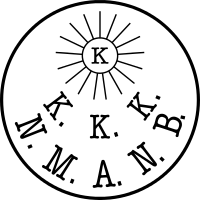

Great Seal

| |||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||||

| Capital | Tondo, Manila | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Tagalog, Philippine languages | ||||||||||

| Government | Revolutionary republic | ||||||||||

| President / Supreme Leader | |||||||||||

| Legislature | Kataas-taasang Sanggunian (Supreme Council) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Philippine Revolution | ||||||||||

| August 24 1896 | |||||||||||

| August 30, 1896 | |||||||||||

| September 1, 1896 | |||||||||||

| December 30, 1896 | |||||||||||

| December 31, 1896 | |||||||||||

| March 22, 1897 | |||||||||||

| May 10 1897 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Peso | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

In the last days of August, the Katipunan members met in Caloocan and decided to start their revolt[1] (the event was later called the "Cry of Balintawak" or "Cry of Pugad Lawin"; the exact location and date are disputed). A day after the Cry, the Supreme Council of the Katipunan held elections, with the following results:[1][2]

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| President / Supremo | Andrés Bonifacio |

| Secretary of War | Teodoro Plata |

| Secretary of State | Emilio Jacinto |

| Secretary of the Interior | Aguedo del Rosario |

| Secretary of Justice | Briccio Pantas |

| Secretary of Finance | Enrique Pacheco |

The above was divulged to the Spanish by the Katipunan member Pío Valenzuela while in captivity.[1][2] Teodoro Agoncillo thus wrote:

| “ | Immediately before the outbreak of the revolution, therefore, Bonifacio organized the Katipunan into a government revolving around a ‘cabinet’ composed of men of his confidence.[9] | ” |

Milagros C. Guerrero and others have described Bonifacio as "effectively" the commander-in-chief of the revolutionaries. They assert:

| “ | As commander-in-chief, Bonifacio supervised the planning of military strategies and the preparation of orders, manifests and decrees, adjudicated offenses against the nation, as well as mediated in political disputes. He directed generals and positioned troops in the fronts. On the basis of command responsibility, all victories and defeats all over the archipelago during his term of office should be attributed to Bonifacio.[1] | ” |

One name for Bonifacio's concept of the Philippine nation-state appears in surviving Katipunan documents: Haring Bayang Katagalugan ("Sovereign Nation of the Tagalog People", or "Sovereign Tagalog Nation") - sometimes shortened into Haring Bayan ("Sovereign Nation"). Bayan may be rendered as "nation" or "people". Bonifacio is named as the president of the "Tagalog Republic" in an issue of the Spanish periodical La Ilustración Española y Americana published in February 1897 ("Andrés Bonifacio - Titulado "Presidente" de la República Tagala"). Another name for Bonifacio's government was Repúblika ng Katagalugan (another form of "Tagalog Republic") as evidenced by a picture of a rebel seal published in the same periodical the next month.[1][2]

Official letters and one appointment paper of Bonifacio addressed to Emilio Jacinto reveal Bonifacio's various titles and designations, as follows:[1][2]

- President of the Supreme Council

- Supreme President

- President of the Sovereign Nation of Katagalugan / Sovereign Tagalog Nation

- President of the Sovereign Nation, Founder of the Katipunan, Initiator of the Revolution

- Office of the Supreme President, Government of the Revolution

An 1897 power struggle in Cavite led to command of the revolution shifting at the Tejeros Convention, where a new government was formed with Emilio Aguinaldo as President. Bonifacio refused to recognize the new government after his election as Director of the Interior was questioned by Daniel Tirona, for which he was later executed. After Bonifacio's execution, the Philippine Republic, usually considered the "First Philippine Republic", was formally established in 1899, after a succession of revolutionary and dictatorial governments (e.g. the Tejeros government, the Biak-na-Bato Republic) headed by Aguinaldo.[10][11]

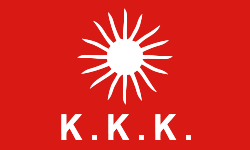

Sakay

| Tagalog Republic Repúbliká ng̃ Katagalugan | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1902–1906 | |||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

|

Anthem: Marangal na Dalit ng Katagalugan | |||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||||

| Capital | Rizal | ||||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

| Vice President | |||||||||||

| Historical era | Philippine–American War | ||||||||||

• Declaration of Independence | May 6 1902 | ||||||||||

• Capture of Macario Sakay | July 14 1906 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

After Emilio Aguinaldo and his men were captured by the US forces in 1901, General Macario Sakay, a veteran Katipunan member, established in 1902 his own Tagalog Republic (Tagalog: Repúbliká ng̃ Katagalugan) in the mountains of Morong (today, the province of Rizal), and held the presidency with Francisco Carreón as vice president.[12] In April 1904, Sakay issued a manifesto declaring Filipino right to self-determination at a time when support for independence was considered a crime by the American colonial government.[13]

| Position | Name |

|---|---|

| President | Macario Sakay |

| Vice President | Francisco Carreón |

| Minister of War | Domingo Moriones |

| Minister of the Government | Alejandro Santiago |

| Minister of State | Nicolás Rivera |

The republic ended in 1906 when Sakay and his leading followers were arrested by American authorities and the following year executed for banditry.[13] Some of its survivors escaped to Japan to be joined with Artemio Ricarte, an exiled Katipunan veteran, and later returned to support the Second Philippine Republic, a client state of Japan, during World War II.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Guerrero, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (2003), "Andrés Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 1 (2): 3–12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Guerrero, Milagros; Schumacher, S.J., John (1998), Reform and Revolution, Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 962-258-228-1

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 177–179

- 1 2 Zaide, Gregorio (1984), Philippine History and Government, National Bookstore Printing Press

- ↑ Constantino 1975, pp. 179–181

- ↑ Borromeo & Borromeo-Buehler 1998, p. 25 (Item 3 in the list, referring to Note 41 at p. 61, citing Guerrero, Encarnacion & Villegas 2003);

^ Borromeo & Borromeo-Buehler 1998, p. 26, "Formation of a revolutionary government";

^ Borromeo & Borromeo-Buehler 1998, p. 135 (in "Document G", Account of Mr. Briccio Brigado Pantas). - ↑ Halili & Halili 2004, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Severino, Howie (November 27, 2007), Bonifacio for (first) president, GMA News .

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p.

- ↑ Zaide, Sonia M. (1994). The Philippines: A Unique Nation. All-Nations Publishing Co. pp. 246–247. ISBN 971-642-071-4.

- ↑ "Eleksion 1897". The Camino Real to Freedom and Other Notes on Philippine History and Culture. The University of Santo Thomas Publishinng House. 2016. pp. 168–170. ISBN 978-971-506-790-4.

- ↑ Kabigting Abad, Antonio (1955). General Macario L. Sakay: Was He a Bandit or a Patriot?. J. B. Feliciano and Sons Printers-Publishers.

- 1 2 Flores, Paul (August 12, 1995). "Macario Sakay: Tulisán or Patriot?". Philippine History Group of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

References

- Agoncillo, Teodoro (1990) [1960], History of the Filipino People (Eighth ed.), R.P. Garcia Publishing Company, ISBN 971-10-2415-2

- Borromeo, Soledad Masangkay; Borromeo-Buehler, Soledad (1998), The cry of Balintawak: a contrived controversy : a textual analysis with appended documents, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-278-8.

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, ISBN 971-8958-00-2.

- Halili, Christine N; Halili, Maria Christine (2004), Philippine History, Rex Bookstore, Inc., ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.