United States Military Government of the Philippine Islands

| United States Military Government of the Philippine Islands | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898–1902 | |||||||||||

Great Seal

| |||||||||||

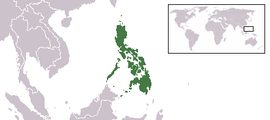

Location of Philippine Islands in Asia | |||||||||||

| Status | Unincorporated territory of the United States | ||||||||||

| Capital | Manila | ||||||||||

| Common languages | English, Tagalog, and other Philippine languages | ||||||||||

| Government | Military occupational transitional government | ||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||

• 1898–1901 | William McKinley | ||||||||||

• 1901–1902 | Theodore Roosevelt | ||||||||||

| Military Governor | |||||||||||

• 1898 | Wesley Merritt | ||||||||||

• 1898–1900 | Elwell S. Otis | ||||||||||

• 1900–1901 | Arthur MacArthur, Jr. | ||||||||||

• 1901–1902 |

Adna Chaffee (jointly with Civil Governor William Howard Taft) | ||||||||||

| Legislature |

Martial law (1898-1900) Philippine Commission (1900-02) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| 14 August 1898 | |||||||||||

| 10 December 1898 | |||||||||||

| 4 February 1899 | |||||||||||

| 31 March 1899 | |||||||||||

| 16 March 1900 | |||||||||||

| 23 March 1901 | |||||||||||

| 16 April 1902 | |||||||||||

| 1 July 1902 | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1898 | 343,385.1 km2 (132,581.7 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1898 | 7300000 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The United States Military Government of the Philippine Islands (Filipino: Pamahalaang Militar ng Estados Unidos sa Kapuluan ng Pilipinas) was a military government in the Philippines established by the United States on August 14, 1898, two days after the capture of Manila, with General Merritt acting as military governor.[4] During military rule (1898–1902), the U.S. military commander governed the Philippines under the authority of the U.S. president as Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces. After the appointment of a civil Governor-General, the procedure developed that as parts of the country were pacified and placed firmly under American control, responsibility for the area would be passed to the civilian.

General Merritt was succeeded by General Otis as military governor, who in turn was succeeded by General MacArthur. Major General Adna Chaffee was the final military governor. The position of military governor was abolished in July 1902, after which the civil Governor-General became the sole executive authority in the Philippines.[5][6]

Under the military government, an American-style school system was introduced, initially with soldiers as teachers; civil and criminal courts were reestablished, including a supreme court;[7] and local governments were established in towns and provinces. The first local election was conducted by General Harold W. Lawton on May 7, 1899, in Baliuag, Bulacan.[8]

Capture of Manila

By June, U.S. and Filipino forces had taken control of most of the islands, except for the walled city of Intramuros. Admiral Dewey and General Merritt were able to work out a bloodless solution with acting Governor-General Fermín Jáudenes. The negotiating parties made a secret agreement to stage a mock battle in which the Spanish forces would be defeated by the American forces, but the Filipino forces would not be allowed to enter the city. This plan minimized the risk of unnecessary casualties on all sides, while the Spanish would also avoid the shame of possibly having to surrender Intramuros to the Filipino forces.[9] On the eve of the mock battle, General Anderson telegraphed Aguinaldo, "Do not let your troops enter Manila without the permission of the American commander. On this side of the Pasig River you will be under fire".[10]

On August 13, with American commanders unaware that a ceasefire had already been signed between Spain and the U.S. on the previous day, American forces captured the city of Manila from the Spanish in the Battle of Manila.[11][12][13] The battle started when Dewey's ships bombarded Fort San Antonio Abad, a decrepit structure on the southern outskirts of Manila, and the virtually impregnable walls of Intramuros. In accordance with the plan, the Spanish forces withdrew while U.S. forces advanced. Once a sufficient show of battle had been made, Dewey hoisted the signal "D.W.H.B." (meaning "Do you surrender?),[14] whereupon the Spanish hoisted a white flag and Manila was formally surrendered to U.S. forces.[15] This battle marked the end of Filipino-American collaboration, as the American action of preventing Filipino forces from entering the captured city of Manila was deeply resented by the Filipinos. This later led to the Philippine–American War,[16] which would prove to be more deadly and costly than the Spanish–American War.

Spanish–American War ends

Article V of the peace protocol signed on August 12 had mandated negotiations to conclude a treaty of peace to begin in Paris not later than October 1, 1898.[17] President McKinley sent a five-man commission, initially instructed to demand no more than Luzon, Guam, and Puerto Rico; which would have provided a limited U.S. empire of pinpoint colonies to support a global fleet and provide communication links.[18] In Paris, the commission was besieged with advice, particularly from American generals and European diplomats, to demand the entire Philippine archipelago.[18] The unanimous recommendation was that "it would certainly be cheaper and more humane to take the entire Philippines than to keep only part of it."[19] On October 28, 1898, McKinley wired the commission that "cessation of Luzon alone, leaving the rest of the islands subject to Spanish rule, or to be the subject of future contention, cannot be justified on political, commercial, or humanitarian grounds.The cessation must be the whole archipeligo or none.The latter is wholly inadmissible, and the former must therefore be required."[20] The Spanish negotiators were furious over the "immodist demands of a conqueror", but their wounded pride was assauged by an offer of twenty million dollars for "Spanish improvements" to the islands. The Spaniards capitulated, and on December 10, 1898, the U.S. and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris, formally ending the Spanish–American War. In Article III, Spain ceded the Philippine archipelago to the United States, as follows: "Spain cedes to the United States the archipelago known as the Philippine Islands, and comprehending the islands lying within the following line: [... geographic description elided ...]. The United States will pay to Spain the sum of twenty million dollars ($20,000,000) within three months after the exchange of the ratifications of the present treaty."[21]

In the U.S., there was a movement for Philippine independence; some said that the U.S. had no right to a land where many of the people wanted self-government. In 1898 Andrew Carnegie, an industrialist and steel magnate, offered to buy the Philippines for $20 million and give it to the Filipinos so that they could be free of United States government.[22]

On November 7, 1900, Spain and the U.S. signed the Treaty of Washington, clarifying that the territories relinquished by Spain to the United States included any and all islands belonging to the Philippine Archipelago, but lying outside the lines described in the Treaty of Paris. That treaty explicitly named the islands of Cagayan Sulu and Sibutu and their dependencies as among the relinquished territories.[23]

Philippine–American War (1899–1902)

Tensions escalate

The Spanish had yielded Iloilo to the insurgents in 1898 for the purpose of troubling the Americans. On January 1, 1899, news had come to Washington from Manila that American forces which had been sent to Iloilo under the command of General Marcus Miller had been confronted by 6,000 armed Filipinos, who refused them permission to land.[24][25] A Filipino official styling himself Presidente Lopez of the Federal Government of the Visayas informed Miller that "foreign troops" would not be landed "without express orders from the central government of Luzon"[25] On December 21, 1898, President McKinley issued a Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation. General Otis delayed its publication until January 4, 1899, then publishing an amended version edited so as not to convey the meanings of the terms "sovereignty", "protection", and "right of cessation" which were present in the unabridged version.[26] Unknown to Otis, the War Department had also sent an enciphered copy of the Benevolent Assimilation proclamation to General Marcus Miller in Iloilo for informational purposes. Miller assumed that it was for distribution and, unaware that a politically bowdlerized version had been sent to Aguinaldo, published it in both Spanish and Tagalog translations which eventually made their way to Aguinaldo.[27] Even before Aguinaldo received the unaltered version and observed the changes in the copy he had received from Otis, he was upset that Otis had altered his own title to "Military Governor of the Philippines" from "... in the Philippines." Aguinaldo did not miss the significance of the alteration, which Otis had made without authorization from Washington.[28]

On January 5, Aguinaldo issued a counter-proclamation summarizing what he saw as American violations of the ethics of friendship, particularly as regards the events in Iloilo. The

proclamation concluded as follows:

| “ | Such procedures, so foreign to the dictates of culture and the usages observed by civilized nations, gave me the right to act without observing the usual rules of intercourse. Nevertheless, in order to be correct to the end, I sent to General Otis commissioners charged to solicit him to desist from his rash enterprise, but they were not listened to.

My government can not remain indifferent in view of such a violent and aggressive seizure of a portion of its territory by a nation which arrogated to itself the title champion of oppressed nations. Thus it is that my government is disposed to open hostilities if the American troops attempt to take forcible possession of the Visayan Islands. I denounce these acts before the world, in order that the conscience of mankind may pronounce its infallable verdict as to who are the true oppressors of nations and the tormentors of human kind.[29] |

” |

After some copies of that proclamation had been distributed, Aguinaldo ordered the recall of undistributed copies and issued another proclamation, which was published the same day in El Heraldo de la Revolucion, the official newspaper of the Philippine Republic. There, he said partly,

| “ | As in General Otis's proclamation he alluded to some instructions edited by His Excellency the President of the United States, referring to the administration of the matters in the Philippine Islands, I in the name of God, the root and fountain of all justice, and that of all the right which has been visibly granted to me to direct my dear brothers in the difficult work of our regeneration, protest most solemnly against this intrusion of the United States Government on the sovereignty of these islands.

I equally protest in the name of the Filipino people against the said intrusion, because as they have granted their vote of confidence appointing me president of the nation, although I don't consider that I deserve such, therefore I consider it my duty to defend to death its liberty and independence.[30] |

” |

Otis, taking these two proclamations as a call to arms, strengthened American observation posts and alerted his troops. In the tense atmosphere, some 40,000 Filipinos fled Manila within

a period of 15 days.[31]

Meanwhile, Felipe Agoncillo, who had been commissioned by the Philippine Revolutionary Government as Minister Plenipotentiary to negotiate treaties with foreign governments, and who had unsuccessfully sought to be seated at the negotiations between the U.S. and Spain in Paris, was now in Washington. On January 6, he filed a request for an interview with the President to discuss affairs in the Philippines. The next day the government officials were surprised to learn that messages to General Otis to deal mildly with the rebels and not to force a conflict had become known to Agoncillo, and cabled by him to Aguinaldo. At the same time came Aguinaldo's protest against General Otis signing himself "Military Governor of the Philippines."[24]

On January 8, Agoncillo gave out this statement:[24]

| “ | In my opinion the Filipino people, whom I represent, will never consent to become a colony dependency of the United States. The soldiers of the Filipino army have pledged their lives that they will not lay down their arms until General Aguinaldo tells them to do so, and they will keep that pledge, I feel confident. | ” |

The Filipino committees in London, Paris and Madrid about this time telegraphed to President McKinley as follows:

| “ | We protest against the disembarkation of American troops at Iloilo. The treaty of peace still unratified, the American claim to sovereignty is premature. Pray reconsider the resolution regarding Iloilo. Filipinos wish for the friendship of America and abhor militarism and deceit.[24] | ” |

On January 8, Aguinaldo received the following message from Teodoro Sandiko:

| “ | To the President of the Revolutionary Government, Malolos, from Sandico, Manila. 8 Jan., 1899, 9.40 p.m..: In consequence of the order of General Rios to his officers, as soon as the Filipino attack begins the Americans should be driven into the Intramuros district and the walled city should be set on fire. Pipi.[32] | ” |

The New York Times reported on January 8, that two Americans who had been guarding a waterboat in Iloilo had been attacked, one fatally, and that insurgents were threatening to destroy the business section of the city by fire; and on January 10 that a peaceful solution to the Iloilo issues may result but that Aguinaldo had issued a proclamation threatening to drive the Americans from the islands.[33][34]

By January 10, insurgents were ready to assume the offensive, but desired, if possible, to provoke the Americans into firing the first shot. They made no secret of their desire for conflict, but increased their hostile demonstrations and pushed their lines forward into forbidden territory. Their attitude is well illustrated by the following extract from a telegram sent by Colonel Cailles to Aguinaldo on January 10, 1899:[35]

| “ | Most urgent. An American interpreter has come to tell me to withdraw our forces in Maytubig fifty paces. I shall not draw back a step, and in place of withdrawing, I shall advance a little farther. He brings a letter from his general, in which he speaks to me as a friend. I said that from the day I knew that Maquinley (McKinley) opposed our independence I did not want any dealings with any American. War, war, is what we want. The Americans after this speech went off pale. | ” |

Aguinaldo approved the hostile attitude of Cailles, for there is a reply in his handwriting which reads:[35]

| “ | I approve and applaud what you have done with the Americans, and zeal and valour always, also my beloved officers and soldiers there. I believe that they are playing us until the arrival of their reinforcements, but I shall send an ultimatum and remain always on the alert.--E. A. Jan. 10, 1899. | ” |

On 31 January 1899, The Minister of Interior of the revolutionary First Philippine Republic, Teodoro Sandiko, signed a decree saying that President Aguinaldo had directed that all idle lands be planted to provide food for the people, in view of impending war with the Americans.[36]

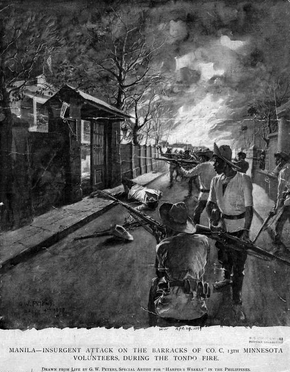

Outbreak of general hostilities

Worcester writes that General Otis' account of the opening of active hostilities was as follows:

| “ | "On the night of February 2 they sent in a strong detachment to draw the fire of our outposts, which took up a position immediately in front and within a few yards of the same. The outpost was strengthened by a few of our men, who silently bore their taunts and abuse the entire night. This was reported to me by General MacArthur, whom I directed to communicate with the officer in command of the insurgent troops concerned. His prepared letter was shown me and approved, and the reply received was all that could be desired. However, the agreement was ignored by the insurgents and on the evening of February 4 another demonstration was made on one of our small outposts, which occupied a retired position at least 150 yards within the line which had been mutually agreed upon, an insurgent approaching the picket and refusing to halt or answer when challenged. The result was that our picket discharged his piece, when the insurgent troops near Santa Mesa opened a spirited fire on our troops there stationed.

"The insurgents had thus succeeded in drawing the fire of a small outpost, which they had evidently labored with all their ingenuity to accomplish, in order to justify in some way their premeditated attack. It is not believed that the chief insurgent leaders wished to open hostilities at this time, as they were not completely prepared to assume the initiative. They desired two or three days more to perfect their arrangements, but the zeal of their army brought on the crisis which anticipated their premeditated action. They could not have delayed long, however, for it was their object to force an issue before American troops, then en route, could arrive in Manila." Thus began the Insurgent attack, so long and so carefully planned for. We learn from the Insurgent records that the shot of the American sentry missed its mark. There was no reason why it should have provoked a hot return fire, but it did. The result of the ensuing combat was not at all what the Insurgents had anticipated. The Americans did not drive very well. It was but a short time before they themselves were routed and driven from their positions. Aguinaldo of course promptly advanced the claim that his troops had been wantonly attacked. The plain fact is that the Insurgent patrol in question deliberately drew the fire of the American sentry, and this was just as much an act of war as was the firing of the shot. Whether the patrol was acting under proper orders from higher authority is not definitely known.[37] |

” |

Other sources name the two specific U.S. soldiers involved in the first exchange of fire as Privates William Grayson and Orville Miller of the Nebraska Volunteers.[38]

Subsequent to the conclusion of the war, after analyzing captured insurgent papers, Major Major J. R. M. Taylor wrote, in part,

| “ | An attack on the United States forces was planned which should annihilate the little army in Manila, and delegations were appointed to secure the interference of foreign powers. The protecting cloak of pretense of friendliness to the United States was to be kept up until the last. While commissioners were appointed to negotiate with General Otis, secret societies were organized in Manila pledged to obey orders of the most barbarous character to kill and burn. The attack from without and the attack from within was to be on a set day and hour. The strained situation could not last. The spark was applied, either inadvertently or by design, on the 4th of February by an insurgent, willfully transgressing upon what, by their own admission, was within the agreed limits of the holding of the American troops. Hostilities resulted and the war was an accomplished fact.[39] | ” |

War

On February 4, Aguinaldo declared "That peace and friendly relations with the Americans be broken and that the latter be treated as enemies, within the limits prescribed by the laws of war."[40] On June 2, 1899, the Malolos Congress enacted and ratified a declaration of war on the United States, which was publicly proclaimed on that same day by Pedro Paterno, President of the Assembly.[41]

As before when fighting the Spanish, the Filipino rebels did not do well in the field. Aguinaldo and his provisional government escaped after the capture of Malolos on March 31, 1899 and were driven into northern Luzon. Peace feelers from members of Aguinaldo's cabinet failed in May when the American commander, General Ewell Otis, demanded an unconditional surrender. In 1901, Aguinaldo was captured and swore allegiance to the United States, marking one end to the war.

First Philippine Commission

President McKinley had appointed a five-person group headed by Dr. Jacob Schurman, president of Cornell University, on January 20, 1899, to investigate conditions in the islands and

make recommendations. The three civilian members of the Philippine Commission arrived in Manila on March 4, 1899, a month after the Battle of Manila which had begun armed conflict between U.S. and revolutionary Filipino forces. The commission published a proclamation containing assurances that the U.S. "... is anxious to establish in the Philippine Islands an enlightened system of government under which the Philippine people may enjoy the largest measure of home rule and the amplest liberty."

After meetings in April with revolutionary representatives, the commission requested authorization from McKinley to offer a specific plan. McKinley authorized an offer of a government consisting of "a Governor-General appointed by the President; cabinet appointed by the Governor-General; [and] a general advisory council elected by the people."[42] The Revolutionary Congress voted unanimously to cease fighting and accept peace and, on May 8, the revolutionary cabinet headed by Apolinario Mabini was replaced by a new "peace" cabinet headed by Pedro Paterno. At this point, General Antonio Luna arrested Paterno and most of his cabinet, returning Mabini and his cabinet to power. After this, the commission concluded that "... The Filipinos are wholly unprepared for independence ... there being no Philippine nation, but only a collection of different peoples."[43]

In the report that they issued to the president the following year, the commissioners acknowledged Filipino aspirations for independence; they declared, however, that the Philippines was not ready for it.[44]

| “ | On November 2, 1899, The commission issued a preliminary report containing the following statement:

|

” |

Specific recommendations included the establishment of civilian government as rapidly as possible (the American chief executive in the islands at that time was the military governor), including establishment of a bicameral legislature, autonomous governments on the provincial and municipal levels, and a system of free public elementary schools.[47]

Second Philippine Commission

The Second Philippine Commission (the Taft Commission), appointed by McKinley on March 16, 1900, and headed by William Howard Taft, was granted legislative as well as limited executive powers.[48] On September 1, the Taft Commission began to exercise legislative functions.[49] Between September 1900 and August 1902, it issued 499 laws, established a judicial system, including a supreme court, drew up a legal code, and organized a civil service.[50] The 1901 municipal code provided for popularly elected presidents, vice presidents, and councilors to serve on municipal boards. The municipal board members were responsible for collecting taxes, maintaining municipal properties, and undertaking necessary construction projects; they also elected provincial governors.[47]

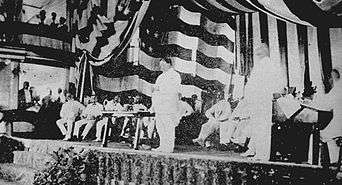

Establishment of civil government

On March 3, 1901 the U.S. Congress passed the Army Appropriation Act containing (along with the Platt Amendment on Cuba) the Spooner Amendment which provided the President with legislative authority to establish of a civil government in the Philippines.[51] Up until this time, the President been administering the Philippines by virtue of his war powers.[52] On July 1, 1901, civil government was inaugurated with William H. Taft as the Civil Governor. Later, on February 3, 1903, the U.S. Congress would change the title of Civil Governor to Governor-General.[53]

A highly centralized public school system was installed in 1901, using English as the medium of instruction. This created a heavy shortage of teachers, and the Philippine Commission authorized the Secretary of Public Instruction to bring to the Philippines 600 teachers from the U.S.A. — the so-called Thomasites. Free primary instruction that trained the people for the duties of citizenship and avocation was enforced by the Taft Commission per instructions of President McKinley.[54] Also, the Catholic Church was disestablished, and a considerable amount of church land was purchased and redistributed.

Official end to the war

_Reception-Taft.jpg)

The Philippine Organic Act of July 1902 approved, ratified, and confirmed McKinley's Executive Order establishing the Philippine Commission, and also stipulated that the bicameral Philippine Legislature would be established composed of an elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly and the appointed Philippine Commission as the upper house. The act also provided for extending the United States Bill of Rights to the Philippines.[47][55]

On July 2, 1902 the Secretary of War telegraphed that the insurrection against the sovereign authority of the U.S. having come to an end, and provincial civil governments having been established, the office of Military Governor was terminated.[6] On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the U.S. Presidency after the assassination of President McKinley on September 5, 1901 proclaimed a full and complete pardon and amnesty to all persons in the Philippine archipelago who had participated in the conflict.[6][56]

On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo proclaimed that the Philippine–American War had ended on April 16, 1902 with the surrender of General Miguel Malvar, and declared the centennial anniversary of that date as a national working holiday and as a special non-working holiday in the Province of Batangas and in the Cities of Batangas, Lipa and Tanaun.[57]

Post-1902 hostilities

Some sources have suggested that the war unofficially continued for nearly a decade, since bands of guerrillas, quasi-religious armed groups and other resistance groups continued to roam the countryside, still clashing with American Army or Philippine Constabulary patrols. American troops and the Philippine Constabulary continued hostilities against such resistance groups until 1913.[58] Some historians consider these unofficial extensions to be part of the war.[59]

Comparisons with the First Philippine Republic

| Established | 14 August 1898 | 23 January 1899 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional Document | War powers authority of the President | Malolos Constitution | |

| Capital | Manila | Malolos, Bulacan | |

| Head of State | President of the United States

|

President of the Philippines

| |

| Head of Government | Military Governor of the Philippine Islands

|

Prime Minister of the Philippines

| |

| Legislative | Martial Law (1898-1900) Philippine Commission (1900-1902) |

National Assembly | |

| Military | United States Armed Forces | Philippine Republican Army | |

| Currency | Peso | Peso | |

| Official Language(s) | English | Spanish, Tagalog | |

See also

- First Philippine Republic – an All-Filipino nascent revolutionary government opposed to the United States Military Government in the Philippines.

- History of the Philippines (1898–1946)

References

Citations

- ↑ "PHILIPPINES: More People Practice Tribal Religions Today, than in 1521. However…". The ASWANG Project. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

- ↑ "Population of the Philippines : />Census Years 1799 to 2010". National Statistics Office of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 2012-07-04. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 719. ISBN 978-1-85109-951-1.

- ↑ Halstead 1898, pp. 110–112

- ↑ Elliott 1917, p. 509.

- 1 2 3 "GENERAL AMNESTY FOR THE FILIPINOS; Proclamation Issued by the President" (PDF). The New York Times. July 4, 1902.

- ↑ Otis, Elwell Stephen (1899). "Annual report of Maj. Gen. E.S. Otis, U.S.V., commanding Department of the Pacific and 8th Army Corps, military governor in the Philippine Islands". Annual Report of the Major-General Commanding the Army. 2. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 146.

- ↑ Zaide 1994, p. 279Ch.21

- ↑ Karnow 1990, p. 123

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, p. 196

- ↑ The World of 1898: The Spanish–American War, U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved 2014-06-15

- ↑ The World of 1898: the Spanish–American War, U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved October 10, 2007

- ↑ "Our flag is now waving over Manila", San Francisco Chronicle, retrieved December 20, 2008

- ↑ Trask 1996, p. 419

- ↑ Karnow 1990, pp. 123–4, Wolff 2006, p. 119

- ↑ Lacsamana 2006, p. 126.

- ↑ Halstead 1898, pp. 176–178Ch.15

- 1 2 Miller 1984, p. 20

- ↑ Miller 1984, pp. 20–1

- ↑ Miller 1984, p. 24

- ↑ Kalaw 1927, pp. 430–445 Appendix D

- ↑ Andrew Carnegie timeline of events at PBS.org

- ↑ "TREATY BETWEEN SPAIN AND THE UNITED STATE FOR CESSION OF OUTLYING ISLANDS OF THE PHILIPPINES" (PDF). University of the Philippines. November 7, 1900. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Halstead 1898, p. 316

- 1 2 Miller 1984, p. 50

- ↑ The text of the amended version published by General Otis is quoted in its entirety in José Roca de Togores y Saravia; Remigio Garcia; National Historical Institute (Philippines) (2003). Blockade and siege of Manila. National Historical Institute. pp. 148–50. ISBN 978-971-538-167-3.

See also Wikisource:Letter from E.S. Otis to the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands, January 4, 1899. - ↑ Wolff 2006, p. 200

- ↑ Miller 1984, p. 52

- ↑ Agoncillo 1997, pp. 356–7.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1997, p. 357.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1997, pp. 357–8.

- ↑ Taylor 1907, p. 39

- ↑ "BLOODSHED AT ILOILO; Two Americans Attacked and One Fatally Wounded by Natives." (PDF), The New York Times, January 8, 1899, retrieved 2008-02-10

- ↑ "THE PHILIPPINE CLIMAX; Peaceful Solution of the Iloilo Issue May Result To-day. AGUINALDO'S SECOND ADDRESS He Threatened to Drive the Americans from the Islands -- Manifesto Was Recalled" (PDF), The New York Times, January 10, 1899, retrieved 2008-02-10

- 1 2 Worcester 1914, p. 93Ch.4

- ↑ Guevara 1972, p. 124

- ↑ Worcester 1914, p. 96Ch.4

- ↑ Blitz 2000, p. 32, Blanchard 1996, p. 130

- ↑ Taylor 1907, p. 5

- ↑ Halstead 1918, p. 318Ch.28

- ↑ Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200Ch.7

- ↑ Golay 1997, p. 49.

- ↑ Golay 1997, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Worcester 1914, p. 199Ch.9

- ↑ "The Philippines : As viewed by President McKinley's Special Commissioners". The Daily Star. 7 (2214). Fredricksburg, Va. November 3, 1899.

- ↑ Report Philippine Commission, Vol. I, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 Seekins 1993

- ↑ Kalaw 1927, p. 453Appendix F

- ↑ Zaide 1994, p. 280Ch.21

- ↑ Chronology for the Philippine Islands and Guam in the Spanish–American War, U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved 2008-02-16

- ↑ Piedad-Pugay, Chris Antonette. "The Philippine Bill of 1902: Turning Point in Philippine Legislation". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ↑ Jernegan 2009, pp. 57–58

- ↑ Zaide 1994, p. 281Ch.21

- ↑ Historical Perspective of the Philippine Educational System, RP Department of education, archived from the original on 2011-07-16, retrieved 2008-03-11

- ↑ The Philippine Bill of July 1902, Chan Robles law library, July 1, 1902, retrieved 2010-07-31

- ↑ Worcester 1914, p. 180Ch.9

- ↑ "Presidential Proclamation No. 173 S. 2002". Official Gazette. April 9, 2002.

- ↑ "PNP History", Philippine National Police, Philippine Department of Interior and Local Government, archived from the original on 2008-06-17, retrieved 29 August 2009

- ↑ Constantino 1975, pp. 251–3

Bibliography

- Agoncillo, Teodoro Andal (1990), "11. The Revolution Second Phase", History of the Filipino People (Eighth ed.), University of the Philippines, pp. 187–198, ISBN 971-8711-06-6

- Agoncillo, Teodoro Andal (1997), Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic, University of the Philippines Press, ISBN 978-971-542-096-9

- Blanchard, William H. (1996), "9. Losing Stature in the Philippines", Neocolonialism American Style, 1960-2000, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-30013-5

- Blitz, Amy (2000), "Conquest and Coercion: Early U.S. Colonialism, 1899-1916", The Contested State: American Foreign Policy and Regime Change in the Philippines, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-8476-9935-8

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, ISBN 971-8958-00-2

- Elliott, Charles Burke (1917), The Philippines: To the End of the Commission Government, a Study in Tropical Democracy

- Golay, Frank H. (1997), Face of empire: United States-Philippine relations, 1898-1946, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-254-2 .

- Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (2005), The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899, Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library (published 1972) (English translation by Sulpicio Guevara)

- Halstead, Murat (1898), The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico

- Halstead, Murat (1918), The Story of the Philippines by Murat Halstead, Project Gutenberg

- Jernegan, Prescott F (2009), The Philippine Citizen, BiblioBazaar, LLC, ISBN 978-1-115-97139-3

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial

- Karnow, Stanley (1990), In Our Image, Century, ISBN 978-0-7126-3732-9

- Lacsamana, Leodivico Cruz (2006), Philippine history and government, Phoenix Publishing House, ISBN 978-971-06-1894-1

- Miller, Stuart Creighton (1984), Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899-1903 (4th edition, reprint ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-03081-5

- Seekins, Donald M. (1993), "The First Phase of United States Rule, 1898-1935", in Dolan, Ronald E., Philippines: A Country Study (4th ed.), Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress

- Taylor, John R.M., ed. (1907), Compilation of Philippine Insurgent Records, Arms Research Library, originally from War Department, Bureau of Insular Affairs External link in

|publisher=(help) - Trask, David F. (1996), The war with Spain in 1898, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-9429-5

- Wolff, Leon (2006), Little brown brother: how the United States purchased and pacified the Philippine Islands at the century's turn, History Book Club (published 2005), ISBN 978-1-58288-209-3 (Introduction, Decolonizing the History of the Philippine–American War, by Paul A. Kramer dated December 8, 2005)

- Worcester, Dean Conant (1914), The Philippines: Past and Present (vol. 1 of 2), ISBN 1-4191-7715-X

- Zaide, Sonia M. (1994), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing Co., ISBN 971-642-071-4

.svg.png)