Shenzhen

| Shenzhen 深圳市 | |

|---|---|

| Prefecture-level and Sub-provincial city | |

Top:East Pacific Center, KK100, Shun Hing Square Middle:Shenzhen Stock Exchange, Coastal City Bottom:Shenzhen Bay at night | |

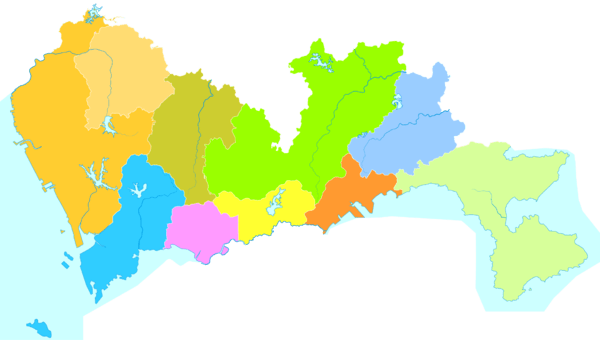

Location of Shenzhen City jurisdiction in Guangdong | |

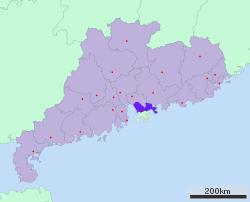

Shenzhen Location in China | |

| Coordinates: 22°33′N 114°06′E / 22.550°N 114.100°ECoordinates: 22°33′N 114°06′E / 22.550°N 114.100°E | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Guangdong |

| County-level divisions | 9 |

| City | 1 March 1979 |

| SEZ formed | 1 May 1980 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sub-provincial city |

| • CPC Committee Secretary | Wang Weizhong |

| • Mayor | Chen Rugui |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level and Sub-provincial city | 2,050 km2 (790 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,748 km2 (675 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0–943.7 m (0–3,145.7 ft) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Prefecture-level and Sub-provincial city | 12,528,300 |

| • Density | 6,100/km2 (16,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2018)[2] | 12,905,000 |

| • Urban density | 7,400/km2 (19,100/sq mi) |

| • Metro[3] | 23,300,000 |

| • Major ethnicities | Han |

| Demonym(s) | Shenzhener |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 518000 |

| Area code(s) | 755 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-GD-03 |

| GDP (Nominal) | 2017[4] |

| - Total |

¥2.24 trillion $332 billion ($0.64 trillion, PPP) |

| - Per capita |

¥183,645 $27,199 ($52,335, PPP)[5] |

| - Growth |

|

| Licence plate prefixes | 粤B |

| City flower | Bougainvillea |

| City trees | Lychee and Mangrove[6] |

| Website | sz.gov.cn |

| Shenzhen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) "Shenzhen" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 深圳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanyu Pinyin |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cantonese Yale | Sāmjan or Sàmjan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Shumchun | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Deep Drains" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shenzhen ([ʂə́n.ʈʂə̂n] (![]()

Shenzhen, which roughly follows the administrative boundaries of Bao'an County, was made a city in 1979, and was named after the then-county town, whose train station was the last stop on the Chinese section of the Kowloon–Canton Railway.[7] In 1980 Shenzhen was designated China's first Special Economic Zone.[8] Shenzhen's registered population in 2017 is estimated to be at 12,905,000.[9] However, officials estimate that the population of Shenzhen is about 20 million due to the large unregistered floating migrant population living in the city.[10][11] Shenzhen was one of the fastest-growing cities in the world in the 1990s and the 2000s.[12]

Shenzhen's modern cityscape is the result of its vibrant economy made possible by rapid foreign investment since the institution of the policy of "reform and opening" in 1979.[13] The city is a leading global technology hub, dubbed the next Silicon Valley.[14][15][16]

Shenzhen is home to the Shenzhen Stock Exchange as well as the headquarters of numerous multinational companies such as JXD, Vanke, Hytera, CIMC, Shenzhen Airlines, Nepstar, Hasee, Ping An Bank, Ping An Insurance, China Merchants Bank, Tencent, ZTE, Huawei and BYD.[17] Shenzhen ranks 22nd in the 2017 Global Financial Centres Index.[18] It also has one of the busiest container ports in the world.[19]

History

Human habitation in Shenzhen dates back to ancient times. The earliest archaeological remains so far unearthed are shards from a site at Xiantouling on Dapeng Bay, dating back to 5000 BC. From the Han dynasty (third century BC) onwards, the area around Shenzhen was a center of the salt monopoly, thus meriting special imperial protection. Salt pans are still visible around the Pearl River area to the west of the city and are commemorated in the name of Yantian District (盐田, meaning "salt fields").[20][21]

The settlement at Nantou was the political center of the area from early antiquity. In the year 331 AD, six counties covering most of modern southeastern Guangdong were merged into one province or "jun" (郡) named Dongguan with its administrative center at Nantou.[20][21] As well as being a center of the politically and fiscally critical salt trade, the area had strategic importance as a stopping off point for international trade. The main shipping route to India, Arabia and the Byzantine Empire started at Guangzhou. As early as the eighth century, chronicles recorded the Nantou area as being a major commercial center, and reported that all foreign ships in the Guangzhou trade would stop there. It was also as a naval defense center guarding the southern approaches to the Pearl River.[22]

Shenzhen was also involved in the events surrounding the end of the Southern Song dynasty (1276–79). The imperial court, fleeing Kublai Khan’s forces, established itself in the Shenzhen area. Lu Xiufu, the then-chief minister, realized all was lost and knew the Mongolian forces would soon take over the area, he preferred suicide instead of the emperor being captured which might have brought shame to the dynasty.[20][21] He jumped off a cliff with Emperor Bing, aged 7, the last emperor of the Southern Song Dynasty strapped to his back, killing both. In the late 19th century the Chiu or Zhao (Zhao was also the Song Imperial surname) clan in Hong Kong identified that Chiwan, an area near Shekou as the final resting place of the Emperor and built a tomb for him. The tomb, since restored, is still at the same location.[23]

The earliest known recorded mention of the name Shenzhen could date from 1410, during the Ming Dynasty.[24] Local people called the drains in paddy fields “zhen” (圳). Shenzhen (深圳) literally means “deep drains” as the area was once crisscrossed with rivers and streams, with deep drains within the paddy fields. The character 圳 is limited in distribution to an area of South China with its most northerly examples in Zhejiang Province which suggests an association with southwards migration during the Southern Song Dynasty (12th and 13th centuries).[25] The County town at Xin'an in modern Nanshan dates from the Ming Dynasty where it was a major naval center at the mouth of the Pearl River. In this capacity it was heavily involved in 1521 in the successful Chinese action against the Portuguese Fleet under Fernão Pires de Andrade. This battle, called the Battle of Tunmen, was fought in the straits between Shekou and Nei Lingding Island.[22]

In November 1979, Bao'an County (宝安县) was promoted to prefecture level, directly governed by Guangdong province. It was renamed Shenzhen, after Shenzhen town. The administrative centre of the county stood approximately around present location of the Dongmen.[20][21]

1980 onwards as a Special Economic Zone

Shenzhen was singled out to be the first of the five Special Economic Zones (SEZ) in May 1980. Initially, the SEZ comprised an area of only 327.5 km2 (126.4 sq mi) of southern Shenzhen, covering the current Luohu, Futian, Nanshan and Yantian districts. The SEZ was created to be an experimental ground for the practice of market capitalism within a community guided by the ideals of "socialism with Chinese characteristics".[26]

In 1982 Bao'an County was re-established, though this time as a part of Shenzhen. The county was converted to become Bao'an District, which was out of the Special Economic Zone. Shenzhen was promoted to a Sub-provincial City in March 1983 and was given the right of provincial-level economic administration in November 1988.[20][21] With a population of 30,000 in 1980, economic development has meant that by 2008 the city has had 12 million inhabitants.[27]

Shenzhen became one of the largest cities in the Pearl River Delta region, which itself is an economic hub of China, as well as the largest manufacturing base in the world.[28]

For five months in 1996, Shenzhen was home to the Provisional Legislative Council and Provisional Executive Council of Hong Kong.[29]

On 1 July 2010, the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone was expanded to include all districts, a five-fold increase over its pre-expansion size. In August 2011, the city hosted the 26th Universiade, an international multi-sport event organized for university athletes.[30]

Geography

| Shenzhen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Shenzhen is located within the Pearl River Delta, bordering Hong Kong to the south, Huizhou to the north and northeast, Dongguan to the north and northwest. Lingdingyang and Pearl River to the west and Mirs Bay to the east and roughly 100 kilometres (62 mi) southeast of the provincial capital of Guangzhou. As of the end of 2017, the resident population of Shenzhen was 12,528,300, of which the registered population was 4,472,200, the actual administrative population was over 20 million.[31] It makes up part of Pearl Delta River built-up area with 44,738,513 inhabitants, spread over 9 municipalities (including Macau). The city is elongated measuring 81.4 kilometers from east to west while the shortest section from north to south is 10.8 kilometers.

Rivers and reservoirs

Over 160 rivers or channels flow through Shenzhen. There are 24 reservoirs within the city limits with a total capacity of 525 million tonnes.[32]

Notable rivers in Shenzhen include the Shenzhen River, Maozhou River and Longgang River.[33]

Islands

Shenzhen is surrounded by many islands. Most of them fall under the territory of neighbouring areas such as Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and Huiyang District, Huizhou. But there are several islands under Shenzhen's jurisdiction, such as Nei Lingding Island, Dachan Island (Tai Shan Island), Xiaochan Island, Mazhou, Laishizhou, Zhouzai and Zhouzaitou. (See List of islands in Shenzhen)

Climate

Although Shenzhen is situated about a degree south of the Tropic of Cancer, due to the Siberian anticyclone it has a warm, monsoon-influenced, humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa). Winters are mild and relatively dry, due in part to the influence of the South China Sea, and frost is very rare; it begins dry but becomes progressively more humid and overcast. However, fog is most frequent in winter and spring, with 106 days per year reporting some fog. Early spring is the cloudiest time of year, and rainfall begins to dramatically increase in April; the rainy season lasts until late September to early October. The monsoon reaches its peak intensity in the summer months, when the city also experiences very humid, and hot, but moderated, conditions; there are only 2.4 days of 35 °C (95 °F)+ temperatures.[34] The region is prone to torrential rain as well, with 9.7 days that have 50 mm (1.97 in) or more of rain, and 2.2 days of at least 100 mm (3.94 in).[34] The latter portion of autumn is dry. The annual precipitation averages at around 1,970 mm (78 in), some of which is delivered in typhoons that strike from the east during summer and early autumn. Extreme temperatures have ranged from 0.2 °C (32 °F) on 11 February 1957 to 38.7 °C (102 °F) on 10 July 1980.[35]

| Climate data for Shenzhen (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.1 (84.4) |

28.9 (84) |

32.0 (89.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.8 (96.4) |

36.9 (98.4) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37.1 (98.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

35.2 (95.4) |

33.1 (91.6) |

29.8 (85.6) |

38.7 (101.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.3 (79.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.1 (88) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

29.2 (84.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 15.4 (59.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.9 (84) |

28.7 (83.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.1 (79) |

25.0 (77) |

22.5 (72.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

0.2 (32.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.0 (68) |

21.1 (70) |

16.9 (62.4) |

9.3 (48.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 26.4 (1.039) |

47.9 (1.886) |

69.9 (2.752) |

154.3 (6.075) |

237.1 (9.335) |

346.5 (13.642) |

319.7 (12.587) |

354.4 (13.953) |

254.0 (10) |

63.3 (2.492) |

35.4 (1.394) |

26.9 (1.059) |

1,935.8 (76.214) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 7.1 | 10.1 | 10.8 | 12.7 | 15.6 | 18.5 | 17.0 | 18.3 | 14.8 | 7.6 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 144.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71.7 | 76.8 | 79.5 | 81.0 | 81.7 | 81.8 | 80.5 | 81.8 | 78.8 | 72.4 | 68.4 | 67.1 | 76.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 138.7 | 92.4 | 94.9 | 104.6 | 146.4 | 160.3 | 215.6 | 182.5 | 169.9 | 189.6 | 175.8 | 166.9 | 1,837.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 44 | 31 | 27 | 29 | 37 | 43 | 53 | 47 | 49 | 55 | 56 | 53 | 44 |

| Source: Shenzhen Meteorological Bureau[34] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

Shenzhen has direct jurisdiction over nine administrative Districts and one New District:

| Administrative divisions of Shenzhen | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division code[36] | Division | Area in km2[37] | Population 2014[38] | Seat | Postal code | Subdivisions | |||

| Subdistricts | Residential communities | ||||||||

| 440300 | Shenzhen | 1996.78 | 10,779,215 | Futian | 518000 | 74 | 775 | ||

| 440303 | Luohu | 78.75 | 953,764 | Huangbei Subdistrict | 518000 | 10 | 115 | ||

| 440304 | Futian | 78.65 | 1,357,103 | Shatou Subdistrict | 518000 | 10 | 115 | ||

| 440305 | Nanshan | 185.49 | 1,135,929 | Nantou Subdistrict | 518000 | 8 | 105 | ||

| 440306 | Bao'an | 398.38 | 2,736,503 | Xin'an Subdistrict | 518100 | 10 | 123 | ||

| 440307 | Longgang

* |

387.82 | 1,975,215 | Longcheng Subdistrict | 518100 | 11 | 111 | ||

| 440308 | Yantian | 74.63 | 216,527 | Haishan Subdistrict | 518081 | 4 | 23 | ||

| 440309 | Longhua | 175.58 | 1,434,593 | Guanlan Subdistrict | 518110 | 6 | 100 | ||

| 440310 | Pingshan | 167.00 | 311,557 | Pingshan Subdistrict | 518118 | 6 | 30 | ||

| 440311 | Guangming | 155.44 | 504,203 | Guangming Subdistrict | 518107 | 6 | 28 | ||

| Dapeng | 295.05 | 133,821 | Dapeng Subdistrict | 518116 | 3 | 25 | |||

| Qianhai | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Pinyin | Guangdong Romanization | Kejiahua Pinyin Fang'an |

| Shenzhen City | 深圳市 | Shēnzhèn Shì | sem1 zen3 xi5 | cim1 zun4 si4 |

| Luohu District | 罗湖区 | Luóhú Qū | lo4 wu4 kêu1 | lo2 fu2 ki1 |

| Futian District | 福田区 | Fútián Qū | fug1 tin4 kêu1 | fuk5 tien2 ki1 |

| Nanshan District | 南山区 | Nánshān Qū | nam4 san1 kêu1 | lam5/nam5 san1 ki1 |

| Bao'an District | 宝安区 | Bǎo'ān Qū | bou2 on1 kêu1 | bau3 on1 ki1 |

| Longgang District | 龙岗区 | Lónggǎng Qū | lung4 gong1 kêu1 | lung2 gong1 ki1 |

| Yantian District | 盐田区 | Yántián Qū | yim4 tin4 kêu1 | yam2 tien2 ki1 |

| Longhua District | 龙华区 | Lónghuá Qū | lung4 wa4 kêu1 | lung2 fa2 ki1 |

| Pingshan District | 坪山区 | Píngshān Qū | ping4 san1 kêu1 | piang2 san1 ki1 |

| Guangming District | 光明区 | Guāngmíng Qū | guong1 ming4 kêu1 | gong1 min2 ki1 |

| Dapeng New District | 大鹏新区 | Dàpéng Xīnqū | dai6 pang4 sen1 kêu1 | tai4 pen2 sin1 ki1 |

| Qianhai | 前海 | Qiánhǎi | qin4 hoi2 | |

The Special Economic Zone (SEZ) comprised only Luohu, Futian, Nanshan, and Yantian districts until 1 July 2010, when the SEZ was expanded to include all the other districts, a five-fold increase over its pre-expansion size.

Adjacent to Hong Kong in southern China, Luohu is the financial and trading center of Shenzhen. Futian, at the heart of the SEZ, is the seat of the Municipal Government. West of Futian, Nanshan is the center for high-tech industries. Formerly outside the SEZ, Bao'an and Longgang are located to the north-west and north-east, respectively, of central Shenzhen. Yantian is the location of Yantian Port, the second busiest container terminal in mainland China and the third busiest in the world.

Special Economic Zone Border

Land borders between Shenzhen SEZ and the rest of China existed before 2010. The border was known as 二线关 (pinyin: èr xiàn guān).

The border was set up since the establishment of the SEZ. Initially, the border control was relatively strict, requiring non-Shenzhen citizens to obtain special permissions for entering. Over the years, border controls have gradually weakened, and permission requirement has been abandoned.

On 1 July 2010, the original SEZ border control was cancelled, and the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone was expanded to the whole city. The area of Shenzhen SEZ thus increased from 396 square kilometres (153 sq mi) to 1,953 square kilometres (754 sq mi).[39] Since June 2015 the existing unused border structures have been demolished and are being transformed into urban greenspaces and parks.[40][41][42] On 15 January 2018, the State Council approved the removal of the barbed wire fence set up to mark the boundary of the SEZ.[43][44]

Although the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone have been extended to cover the whole of Shenzhen, colloquially Shenzhen is still said to be separated into two areas, with the original four districts comprising the SEZ before 2010 as "关内" (pinyin: guān nèi; literally: "within the border") and the rest known as "关外" (pinyin: guān wài; literally: "outside of the border").[45]

Demographics

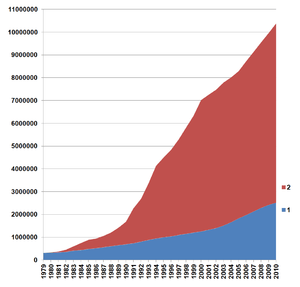

Legend:

Shenzhen has seen its population and activity develop rapidly since the establishment of the SEZ. Shenzhen has an official population of over 10 million. About six million are registered non-local migrant workers who may return to their home town/city on the weekends and live in factory dormitories during the week. The population growth of Shenzhen proper slowed down to less than one percent per year by 2013 with growth spilling over the municipal border and forming a contiguous urban area with southern Dongguan and Huizhou Cities. However, due to the large unregistered floating migrant population living in the city, official estimates put Shenzhen's population at around 20 million inside the administrative area given at any specific moment.[10][11] Shenzhen is the largest migrant city in China.[46]

There had been migration into southern Guangdong province and what is now Shenzhen since the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) but the numbers increased dramatically since Shenzhen was established in the 1980s. In Guangdong province, it is the only city where the local languages (Cantonese, Shenzhen-Hakka and Teochew) is not the main language; it is Mandarin that is mostly spoken, with migrants/immigrants from all over China. At present, the average age in Shenzhen is less than 30. The age range is as follows: 8.49% between the age of 0 and 14, 88.41% between the age of 15 and 59, and 3.1% aged 65 or above.[47]

The population structure has great diversity, ranging from intellectuals with a high level of education to migrant workers with poor education.[48] It was reported in June 2007 that more than 20 percent of China's PhD graduates had worked in Shenzhen.[49] Shenzhen was also elected as one of the top 10 cities in China for expatriates. Expatriates choose Shenzhen as a place to settle because of the city’s job opportunities as well as the culture’s tolerance and open-mindedness, and it was even voted China’s Most Dynamic City and the City Most Favored by Migrant Workers in 2014.

According to a survey by the Hong Kong Planning Department, the number of cross-border commuters increased from about 7,500 in 1999 to 44,600 in 2009. More than half of them lived in Shenzhen.[50] Though neighboring each other, daily commuters still need to pass through customs and immigration checkpoints, as travel between the SEZ and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) is restricted.

Mainland residents who wish to enter Hong Kong for visit are required to obtain an "Exit-Entry Permit for Travelling to and from Hong Kong and Macao". Shenzhen residents can have a special 1 year multiple-journey endorsement (but maximum 1 visit per week starting from April 13, 2015) This type of exit endorsement is only issued to people who have hukou in certain regions.[51](See Exit-Entry Permit for Travelling to and from Hong Kong and Macau.)

Metropolitan area

The encompassing metropolitan area was estimated by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) to have, as of 2010, a population of 23.3 million.[52][3]

Languages

Prior to the establishment of Special Economic Zone, the indigenous local communities could be divided into Cantonese and Hakka speakers,[53] which were two cultural and linguistic sub-ethnic groups vernacular to Guangdong province. Two Cantonese varieties were spoken locally. One was a fairly standard version, known as standard Cantonese. The other, spoken by several villages south of Fuhua Rd. was called Weitou dialect.[54] Two or three Hong Kong villages south of the Shenzhen River also speak this dialect. This is consistent with the area settled by people who accompanied the Southern Song court to the south in the late 13th century.[55] Younger generations of the Cantonese communities now speak the more standard version. Today, some aboriginals of the Cantonese and Hakka speaking communities disperse into urban settlements (e.g. apartments and villas), but most of them are still clustering in their traditional urban and suburban villages.[56]

The influx of migrants from other parts of the country has drastically altered the city's linguistic landscape, as Shenzhen has undergone a language shift towards Mandarin, which was both promoted by the Chinese Central Government as a national lingua franca and natively spoken by most of the out-of-province immigrants and their descendants.[57][58] Despite the ubiquity of Mandarin Chinese, local languages such as Cantonese, Hakka, and Teochew are still commonly spoken among locals. Hokkien and Xiang are also sometimes observed.

Mandarin native speakers, whose majority are out-of-province immigrants are found unwilling to learn Cantonese, Hakka or Teochew, due to the perceived complexities of learning the dialects as well as Mandarin's official use, educational priority, and use as a lingua franca.[59] However, in recent years multilingualism is on the rise as descendants of immigrants begin to assimilate into the local culture through friends, television and other media.[60]

Religion

Religion in Shenzhen (2010)[61]

According to the Department of Religious Affairs of the Shenzhen Municipal People's Government, the two main religions present in Shenzhen are Buddhism and Taoism. Every district also has Protestant churches, Catholic churches, and mosques.[62] According to a 2010 survey held by the University of Southern California, approximately 37% of Shenzhen's residents were practitioners of Chinese folk religions, 26% were Buddhists, 18% Taoists, 2% Christians and 2% Muslims; 15% were unaffiliated to any religion.[61] Most new migrants to Shenzhen rely upon the common spiritual heritage drawn from Chinese folk religion.[63][64] Shenzhen also hosts the headquarters of the Holy Confucian Church, established in 2009.[65]

Hongfa Temple, a popular Buddhist temple in Shenzhen

Hongfa Temple, a popular Buddhist temple in Shenzhen Temple of Guandi

Temple of Guandi

Economy

City economic overview

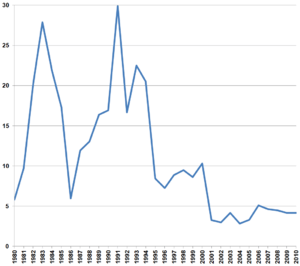

Shenzhen was the first of the Special Economic Zones to be established by Deng Xiaoping and it showed the most rapid growth, averaging at a very high growth rate of 40% per year between 1981 and 1993, compared to the average GDP growth of 9.8% for the country as a whole.[66] The economic growth later slowed after this early breakneck pace. From 2001 to 2005, Shenzhen's overall GDP grew by 16.3 percent yearly on average. Since 2012, economic growth has slowed to around 10% per year. In 2016, Shenzhen's overall GDP grew about 8% per year.

Shenzhen's economic output is ranked 3rd among the 659 Chinese cities (behind Beijing, Shanghai). The city was ranked 19th in the 2016 Global Financial Centres Index.[67] In the 2017 Global Financial Centres Index, Shenzhen was ranked as having the 22nd most competitive financial center in the world.[68]

In 2016, Shenzhen's GDP totaled $303.37 billion, putting it on par with a mid-sized Chinese province by terms of total GDP. Its total economic output is higher than that of small countries like Portugal, the Republic of Ireland, and Vietnam. Its ppp per-capita GDP was $49,185 (unregistered migrant population not counted) as of 2016, on par with developed countries such as Australia and Germany.

In 2017, Shenzhen's economic output totalled $338 billion, surpassing that of Guangzhou, Hong Kong for the first time and ranked No.3 in China, only behind Shanghai and Beijing. Its new status will allow the city to become the leading economic engine in China's Greater Bay Area Initiative.

Shenzhen is a major manufacturing center in China. In the financial sector, large Chinese banks such as Ping An Bank and China Merchants Bank have their headquarters in Shenzhen.

In the 1990s, Shenzhen was described as constructing "one high-rise a day and one boulevard every three days". The Shenzhen's rapidly growing skyline is regarded among the best in the world. It currently has 59 buildings at over 200 meters tall, including the 599 m tall Ping An Finance Centre (the fourth-tallest building in the world) and the 442 m tall Kingkey 100 (renamed to KK100), the 14th-tallest building in the world.[69]

High-Tech Industry

Shenzhen's most important economic sector lies in its role as the headquarters for many of China's high-tech companies. Shenzhen is home to many internationally successful high-tech companies, including Huawei, Tencent, BYD, Konka, Skyworth, ZTE, Gionee, TP-Link, DJI, BGI (Beijing Genomics Institute), OnePlus, etc.[70] Taiwan's largest company, Hon Hai Group, has a large manufacturing plant based in Shenzhen. Many foreign high-tech companies have their China operations centers located in the Science and Technology Park of the Nanshan District.[71]

Due to its unique status as the first Chinese 'Special Economic Zone', Shenzhen is also an extremely fertile ground for startups, be it by Chinese or foreign entrepreneurs. Successful startups include Petcube, Palette, WearVigo, Notch and Makeblock.[72][73] Shenzhen is also the product development base of the hardware startup accelerator, HAX Accelerator (formerly HAXLR8R).[74]

Industrial zones

- Shenzhen Hi-Tech Industrial Park (SHIP) was founded in September 1996. It covers an area of 11.5 km2 (4.4 sq mi). Industries encouraged in the zone include Biotechnology/Pharmaceuticals, Building/Construction Materials, Chemicals Production and Processing, Computer Software, Electronics Assembly & Manufacturing, Instruments & Industrial Equipment Production, Medical Equipment and Supplies, Research and Development, Telecommunications Equipment.

- Shenzhen Software Park is integrated with Shenzhen Hi-Tech Industry Park, an important vehicle established by Shenzhen Municipal Government to support the development of software industry. The Park was approved to be the base of software production of the National Plan in 2001. The distance between the 010 National Highway and the zone is 20.8 km (12.9 mi). The zone is situated 22 km (14 mi) from the Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport.[75]

Shenzhen Stock Exchange

The Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) is a mutualized national stock exchange under the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) that provides a venue for securities trading.[76] A broad spectrum of market participants, including 540 listed companies, 35 million registered investors and 177 exchange members, create the market. Since its creation in 1990, the SZSE has grown with a market capitalization around 1 trillion yuan (US$122 billion). On a daily basis, around 600,000 deals, valued at US$807 million, trade on the SZSE.

Economic cooperation with Hong Kong

Hong Kong and Shenzhen have close business, trade, and social links as demonstrated by the statistics presented below. Except where noted the statistics are taken from sections of the Hong Kong Government website.[77]

As of September 2016, there are nine crossing points on the boundary between Shenzhen and Hong Kong, among which six are land connections. From west to east these include the Shenzhen Bay Port, Futian Port, Huanggang Port, Man Kam To Port, Luohu Port and Shatoujiao Port. On either sides of each of these ports of entry are road and/or rail transportation.[78][79]

In 2006, there were around 20,500 daily vehicular crossings of the boundary in each direction. Of these 65 percent were cargo vehicles, 27 percent cars and the remainder buses and coaches. The Huanggang crossing was most heavily used at 76 percent of the total, followed by the Futian crossing at 18 percent and Shatoujiao at 6 percent.[80] Of the cargo vehicles, 12,000 per day were container carrying and, using a rate of 1.44 teus/vehicle, this results in 17,000 teus/day across the boundary,[81] while Hong Kong port handled 23,000 teus/day during 2006, excluding trans-shipment trade.[82]

Trade with Hong Kong in 2006 consisted of US$333 billion of imports of which US$298 billion were re-exported. Of these figures 94 percent were associated with China.[83] Considering that 34.5 percent of the value of Hong Kong trade is air freight (only 1.3 percent by weight), a large proportion of this is associated with China as well.[84]

Also in 2006 the average daily passenger flow through the four connections open at that time was over 200,000 in each direction of which 63 percent used the Luohu rail connection and 33 percent the Huanggang road connection.[79] Naturally, such high volumes require special handling, and the largest group of people crossing the boundary, Hong Kong residents with Chinese citizenship, use only a biometric ID card (Home Return Permit) and a thumb print reader. As a point of comparison, Hong Kong’s Chek Lap Kok Airport, the 5th busiest international airport in the world, handled 59,000 passengers per day in each direction.[84]

Hong Kong conducts regular surveys of cross-boundary passenger movements, with the most recent being in 2003, although the 2007 survey will be reported on soon. In 2003 the boundary crossings for Hong Kong Residents living in Hong Kong made 78 percent of the trips, up by 33 percent from 1999, whereas Hong Kong and Chinese residents of China made up 20 percent in 2006, an increase of 140 percent above the 1999 figure. Since that time movement has been made much easier for China residents, and so that group have probably increased further still. Other nationalities made up 2 percent of boundary crossings. Of these trips 67 percent were associated with Shenzhen and 42 percent were for business or work purposes. Of the non-business trips about one third were to visit friends and relatives and the remainder for leisure.[85]

After Shenzhen's attempts to be included in the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge project were rejected in 2004, a separate bridge was conceived connecting Shenzhen on the Eastern side of the Pearl River Delta with the city of Zhongshan on the Western side: the Shenzhen-Zhongshan Bridge.

Qianhai

Qianhai, which means foresea in Chinese language, formally known as the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industries Cooperation Zone, is "a useful exploration for China to create a new opening up layout with a more open economic system."[86] A 15 km2 (5.8 sq mi) area located in western Shenzhen, Qianhai lies at the heart of the Pearl River Delta, adjacent to Shenzhen international airport. Strategically positioned as a zone for the innovation and development of modern services, Qianhai will facilitate closer cooperation between Hong Kong and mainland China, as well as act as the catalyst for industrial reform in the Pearl River Delta.[87] With the goal of loosening capital account restrictions, Qianhai authorities have indicated that Hong Kong banks will be allowed to extend commercial RMB loans to Qianhai-based onshore mainland entities. The People's Bank of China has also indicated that such loans will for the first time not be subject to the benchmark rates set by the central bank for all other loans in the rest of China. According to Anita Fung from HSBC, "This new measure on cross-border lending will enhance the co-operation between Hong Kong and Shenzhen and accelerate cross-border convergence."[86]

Cityscape

The tallest building in Shenzhen is the 599-meter, 115 floor Ping An Finance Centre, which is also the second tallest in China and the fourth tallest building in the world.[88] The second-tallest building is the Kingkey 100, rising 441.8 metres (1,449 ft) and containing 100 floors of office and hotel spaces.[89] Shenzhen is also the home to the Shun Hing Square (Diwang Building), the tallest in Asia (if the antenna is taken into account) when it was built in 1996.[90][91] Most of the city's skyscrapers are concentrated in Nanshan, Luohu and Futian districts. SEG Plaza, in Huaqiangbei, is also a noted landmark at a height of 356 meters (291.6 meters to roof-top[92]). Guomao Building was furthermore the tallest building in China when it was completed in 1985.[93]

There is a significant number of supertalls either proposed, approved or under construction that are well over 300 m (984 ft) in Shenzhen. Ones that have been completed or topped out since 2014 include the China Resources Headquarters, Riverfront Times Square, China Chuneng Tower, Hanking Center, Hon Kwok City Center, Chang Fu Jin Mao Tower, Zhongzhou Holdings Financial Center, East Pacific Business Center, One Shenzhen Bay Tower 7 and Shum Yip Upperhills, among others.

There were more skyscrapers completed in Shenzhen in the year 2016 than in the whole of the USA and Australia combined, such is the rate at which the skyline is being transformed.[94]

Skyline of Futian as viewed from Nanshan, June 2016

Skyline of Futian as viewed from Nanshan, June 2016 View of Huaqiangbei, Futian from Lizhi Park in 2006

View of Huaqiangbei, Futian from Lizhi Park in 2006

Sungang East Road from Renmin North Road

Sungang East Road from Renmin North Road Xinghu Road, viewing South

Xinghu Road, viewing South_Daytime.jpg)

Skyline of Shenzhen as viewed from Shenzhen Bay Park

Skyline of Shenzhen as viewed from Shenzhen Bay Park.jpg) East Pacific Center Towers

East Pacific Center Towers

Transport

Road

Since February 2003, the road border crossing at Huanggang and Lok Ma Chau in Hong Kong has been open 24 hours a day. The journey can be made by private vehicle or by bus. On 15 August 2007, the Lok Ma Chau-Huanggang pedestrian border crossing opened, linking Lok Ma Chau Station with Huanggang. With the opening of the crossing, shuttle buses between Lok Ma Chau transport interchange and Huanggang were terminated.

The planned Shenzhen–Zhongshan Bridge will connect Shenzhen on the Eastern side of the Pearl River Delta with the city of Zhongshan on the Western side. It will consist of a series of bridges and tunnels, starting from Bao'an International Airport on the Shenzhen side. Construction of the proposed 51 km (32 mi) eight-lane link is scheduled to start in 2015, with completion scheduled for 2021.

Taxis are metered and come in 3 colors, red, green and blue, all of which may travel throughout the city. Red taxis and green taxis united in May 2017.[95] Blue taxis are electric-powered that costs similar to the red and green ones, only having no fuel surcharge levied on.

There are also frequent bus and van services from Hong Kong International Airport to Huanggang and most major hotels in Shenzhen. A bus service operated by Chinalink Bus Company operates from Kowloon Station on the Airport Express MTR line (below Elements Mall) direct to the Shenzhen International airport.[96]

As of 29 December 2014, Shenzhen banned passenger vehicles with license plates issued in other places from four of Shenzhen's main districts during peak times on working days.[97]

Port

Shenzhen is connected with Hong Kong (city and airport), Zhuhai and Macau through ferries that leave from and arrive at the Shenshen Shekou new cruise terminal.[98] Additionally, Shenzhen airport is directly connected to Hong Kong airport through a separate ferry terminal.

Additionally, Shenzhen is the third largest container port in the world.[99] The city's 260-kilometre (162 mi) coastline is divided by the main landmass of Hong Kong (namely the New Territories and the Kowloon Peninsula) into two halves, the eastern and the western. Shenzhen’s western port area lies to the east of Lingdingyang in the Pearl River Estuary and possesses a deep water harbour with superb natural shelters. It is about 20 nautical miles (40 km) from Hong Kong to the south and 60 nautical miles (110 km) from Guangzhou to the north. By passing Pearl River system, the western port area is connected with the cities and counties in Pearl River Delta networks; by passing On See Dun waterway, it extends all ports both at home and abroad.

Shenzhen container port handled a record number of containers in 2005, ranking as the world's third-busiest port, after rising trade increased cargo shipments through the city. China International Marine Containers, and other operators of the port handled 16.2 million standard 20-foot (6.1 m) boxes last year, a 19 per cent increase. Investors in Shenzhen are expanding to take advantage of rising volume.

Yantian International Container Terminals, Chiwan Container terminals, Shekou Container Terminals, China Merchants Port and Shenzhen Haixing (Mawan port) are the major port terminals in Shenzhen.[100]

Air

Donghai Airlines, Shenzhen Airlines and Jade Cargo International are located at Shenzhen Bao'an International Airport.[101][102] The airport is 35 kilometres (22 miles) from central Shenzhen and connects the city with many other parts of China, and serves domestic and international destinations. The airport also serves as an Asian-Pacific cargo hub for UPS Airlines.[103] Shenzhen Donghai Airlines has its head office in the Shenzhen Airlines facility on the airport property.[104] SF Airlines has its headquarters in the International Shipping Center.[105]

Shenzhen is also served by Hong Kong International Airport; ticketed passengers can take ferries from the Shekou Cruise Centre and the Fuyong Ferry Terminal to the HKIA Skypier.[106] There are also coach bus services connecting Shenzhen with HKIA.[107]

Railway

Shenzhen city has five large railway stations, located at different parts of the city to service destinations in different directions. The oldest of these, called Shenzhen Railway Station is located at the junction of Jianshe Road, Heping Road and Renmin Nan Road mostly services mediums speed long distance trains and provides links to different parts of China. There are frequent high speed trains to Guangzhou, as well as long-distance trains to Beijing, Shanghai, Changsha, Jiujiang, Maoming, Shantou and other destinations. The train from Hong Kong's Hung Hom MTR station to the Lo Wu and Lok Ma Chau border crossings take 43 minutes and 45 minutes respectively.

Shenzhen West Station is located at Qianhai, Nanshan. This station is used for a small number of long distance trains, such as ones to Hefei.

Shenzhen North Railway Station opened in 2011 in Longhua.[108][109] The station is currently handling high-speed trains to Guangzhou South, Guangzhou North, Changsha, Wuhan, Beijing and intermediate stations on the Beijing–Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong HSR.[110]

Shenzhen East Railway Station was opened in December 2012. It was originally called Buji station after the suburb it is located and was a Grade 3 station along the Guangshen Railway with no passenger services. Now after massive renovations, it currently handles mostly regional rail services.[111]

Pingshan Railway Station was completed in 2013 to serve high-speed trains on the Xiamen–Shenzhen HSR which opened in 2013.

Futian Railway Station was completed by the end of 2015 and began to operate high speed trains to Hong Kong in 2018. It is completely underground, located in the centre of its namesake Futian District. The central location means it is the focal point for most high-speed train services on the Beijing-Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong express rail link route which began plying since 23 September 2018.[112] Connection to West Kowloon Railway Station in Hong Kong which was completed in late 2018, allowed for 15 minute cross-border train journeys.[113]

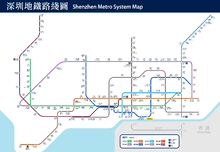

Metro

The Shenzhen Metro system opened on 28 December 2004. Phase I had only two lines: the Luobao line (now Line 1) and Longhua line (now Line 4). The Luobao line ran from Luohu (interchange for Lo Wu MTR station and Shenzhen railway station) to Window of the World (Overseas Chinese Town). The Longhua line ran from Huang Gang (now Futian Checkpoint) to Shaonian Gong (now Children's Palace). In June 2011, the Shenzhen Metro extended Line 1 and Line 4. Line 1 runs from Luohu to Shenzhen Bao'an Airport and Line 4 (now operated by Hong Kong MTR) runs from Futian Checkpoint to Qinghu. Also in June 2011, three lines of Phase II opened before the 26th summer Universiade. They are Line 2 (from Chiwan to Xinxiu), Line 3 (from Yitian to Shuanglong), and Line 5 (from Qianhaiwan to Huangbeiling).[114] The first batch of lines in Phase III, Line 11, opened in June 2016. Lines 7 and 9 opened at the end of 2016. By then the Shenzhen Metro currently has 8 lines, 199 stations, and 286 kilometres (178 mi)[115][116] of lines in operation. This made the Shenzhen Metro one of the top ten longest metro systems in the world.[117] Several additional lines and extensions as part of the second batch of Phase III expansion are under construction and will open by 2020. A number of Phase IV lines have started construction in January 2018.

Sea

Shekou Passenger Terminal in Shekou provides regular ferry transport to and from Zhuhai, Macau, Hong Kong International Airport, Kowloon, and Hong Kong Island.[118]

Fuyong Passenger Terminal in Bao'an near the airport provide services to and from Hong Kong (Hong Kong International Airport) and Macau(Taipa Temporary Ferry Terminal and Outer Harbour Ferry Terminal)[119]

Tourist destinations, parks and resorts

Major tourist attractions of Shenzhen include the China Folk Culture Village, Window of the World, Happy Valley, Splendid China, the Safari Park in Nanshan district, Chung Ying Street (a street dividing Shenzhen and Sha Tau Kok, Hong Kong), Xianhu Botanical Gardens, Minsk World, amongst others. The city also offers free admission to over twenty public city parks [120] including People's Park, Lianhuashan Park, Lizhi Park, Zhongshan Park, and Wutongshan Park.

Overseas Chinese Town (OCT)

The OCT East development in Yantian District is also an events hotspot, featuring the Ecoventure Valley (大侠谷) and the Tea Stream Resort Valley (茶溪谷) theme parks, three scenic themed towns, two 18-hole golf courses and eight themed hotels. OCT East was joined in 2012 by the OCT Bay (欢乐海岸) development in Nanshan, which brought more attractions including an exhibition center, hotels and residences, an artificial beach called CoCo Beach, and an IMAX cinema.[121]

Shekou

Shekou is a former industrial zone with a largely expatriate residential community, also home to a large shopping district called Sea World (海上世界) where a former French cruise liner Minghua (明华), (known in French formerly as MS Ancerville) is cemented into the ground to become a hotel complex.[122] Shekou was expanded and renovated in recent years, partially via land reclamation.

Happy Valley

Happy Valley Shenzhen (欢乐谷) is one of the biggest amusement parks in Shenzhen.

Beaches

Beaches in Shenzhen include Dameisha and Xiaomeisha in Yantian and Xichong Beach in the south of Dapeng Peninsula.

Museums and exhibitions

- Shenzhen Convention and Exhibition Center

- Shenzhen Civic Center

- Shenzhen Cultural Center, where the city's Central Music Hall and library are located

- Shenzhen Shekou Maritime Museum opened to the public on Thursday, June 29[123]

- He Xiangning Art Museum

- Guan Shanyue Art Museum

- OCT Contemporary Art Terminal

Media

Shenzhen News (深圳晚报) is a Chinese-language newspaper serving Shenzhen.

Shenzhen Daily is an English-language news outlet for Shenzhen. It also covers local, national and international news.

ShekouDaily.com is an online media outlet providing news and resources that focus on the Shekou sub-district in Nanshan District of Shenzhen.[124]

Sports

The planned Shenzhen Universiade Sports Center Gymnasium will be one of the venues for the 2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup.[125]

Shenzhen has two local football clubs, Shenzhen F.C. and Shenzhen Renren F.C., who both play home games at the 40,000 capacity Bao'an Stadium. Shenzhen F.C. was one of the earliest professional football clubs in Guangdong, originally owned by memberships, later turned to shareholding.[126] The team won Chinese Super League title in 2004 season despite severe financial problems leaving players unpaid for seven months.[127][128] The team currently plays in China League One, the second tier of Chinese football competition system.

Shenzhen Stadium is a multi-purpose stadium that hosts many events. The stadium is located in Futian District and has a capacity of 32,500. It was built in June 1993, at a cost of 141 million RMB. The 26th Summer Universiade was held in Shenzhen in August 2011.[129] Shenzhen has constructed the sports venues for this first major sporting event in the city.[130]

Shenzhen Dayun Arena is a multipurpose arena. It was completed in 2011 for the 2011 Summer Universiade. It is used for the basketball, ice hockey and gymnastics events. The arena is the home of the Shenzhen KRS Vanke Rays of the Canadian Women's Hockey League.

Shenzhen is also a popular destination for skateboarders from all over the world, due to the architecture of the city and its lax skate laws.[131]

Education

Colleges and universities

- Shenzhen University

- Shenzhen Polytechnic

- Shenzhen Institute of Technology (深圳技师学院)

- Shenzhen Radio and TV University

- Shenzhen Institute of Information Technology

- Shenzhen Graduate School of Peking University

- Shenzhen Graduate School of Tsinghua University

- Harbin Institute of Technology (Shenzhen)

- Shenzhen Technology University

- Southern University of Science and Technology (SUSTech)

- Peking University HSBC Business School

- Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

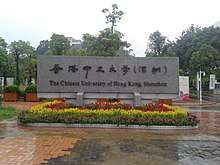

- The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen

- Shanghai Jiao Tong University Antai Economics Management College, Shenzhen

SZU

SZU SUSTech

SUSTech CUHK(SZ)

CUHK(SZ)_Old_Building_(Bachelor).jpg) HIT(SZ)

HIT(SZ)- SZTP

SZEXPS

SZEXPS SZMS

SZMS SZFLS

SZFLS

International schools

Sister cities

Shenzhen has been very active in cultivating sister city relationships. In October 1989, Shenzhen Mayor Li Hao and a delegation traveled to Houston to attend the signing ceremony establishing a sister city relationship between Houston and Shenzhen.[132] Houston became the first sister city of Shenzhen. Up to 2015, Shenzhen has established sister city relationship with 25 cities in the world.

- Houston, United States, March 1986

- Brescia, Italy, November 1991

- Brisbane, Australia, June 1992

- Poznań, Poland, July 1993

- Vienne, France, October 1994

- Kingston, Jamaica, March 1995

- Lomé, Togo, June 1996

- Nuremberg, Germany, May 1997[133]

- Walloon Brabant, Belgium, October 2003

- Tsukuba, Japan, June 2004

- Gwangyang, South Korea, October 2004

- Johor Bahru, Malaysia, July 2006

- Perm, Russia, 2006

- Turin, Italy, January 2007

- Timișoara, Romania, February 2007

- Hull, United Kingdom

- Rotherham, United Kingdom, November 2007

- Luxor, Egypt, 6 September 2007

- Reno, Nevada, United States, 30 April 2008

- Samara, Russia, 19 December 2008

- Montevideo, Uruguay February 2009

- Kalocsa, Hungary, 2011

- Haifa, Israel, 2012

- Barcelona, Spain, July 2012

- Apia, Samoa, August 2015

See also

References

- ↑ "Archived copy" 2017年深圳经济有质量稳定发展 [In 2017, Shenzhen economy will have stable quality and development] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ↑ Cox, W (2018). Demographia World Urban Areas. 14th Annual Edition (PDF). St. Louis: Demographia. p. 22.

- 1 2 OECD Urban Policy Reviews: China 2015, OECD READ edition. OECD iLibrary. OECD. 18 April 2015. p. 37. doi:10.1787/9789264230040-en. ISBN 9789264230033. ISSN 2306-9341. Linked from the OECD here

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org.

- ↑ "ShenZhen Government Online". Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ "昔日边陲小镇深圳的历史渊源".

- ↑ Fish, Isaac Stone (25 September 2010). "A New Shenzhen". Newsweek. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy" 2017年深圳经济有质量稳定发展 [In 2017, Shenzhen economy will have stable quality and development] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- 1 2 李注. "深圳将提高户籍人口比例 今年有望新增38万_深圳新闻_南方网". sz.Southcn.com. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- 1 2 "深圳大幅放宽落户政策 一年户籍人口增幅有望超过10%". finance.Sina.com.cn. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ "Shenzhen". U.S. Commercial Service. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ↑ "Shenzhen Continues to lead China's reform and opening-up". Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ "The next Silicon Valley? It could be here". Das Netz. 11 July 2017.

- ↑ "Shenzhen is a hothouse of innovation". The Economist.

- ↑ "Shenzhen aims to be global technology innovation hub - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn.

- ↑ "Inside Shenzhen: China's Silicon Valley". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ "The Global Financial Centres Index 19". Long Finance. March 2016. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ "The JOC Top 50 World Container Ports". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shenzhen Municipal Government (12 July 2011). 深圳概貌. 深圳政府在线. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 深圳历史沿革. China Central Television. 7 August 2003. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- 1 2 Rule, Ted and Karen, “Shenzhen, the Book”, Hong Kong 2014

- ↑ “少帝在赤湾“ Shenzhen 2005

- ↑ 深圳地名网 (27 May 2010). 深圳地名. Shenzhen Government (深圳政府在线). Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Zhou and You, 方言与中国文化, Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe 2006

- ↑ "The spirit of enterprise fades: Capitalism in China". The Economist. 394 (8666): 61. 23 January 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ↑ Yeung, Yue-man (Fall 2009). "China's Openness and Reform at 30: Retrospect and Prospect". China Review. Chinese University Press. 9 (2): 160. JSTOR 23462283.

- ↑ "UN report: World's biggest cities merging into 'mega-regions'". Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ "Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region – History of the Legislature". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ "Universiade Shenzhen 2011". Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "Shenzhen overview/深圳概貌". Retrieved 25 Sep 2018.

- ↑ "市情概貌". Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ "深圳310条河流 173条黑脏臭 径流小是先天的硬伤". Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 "[气候统计] 深圳市气候资料(来源:深圳市气象局)" [气候统计] 深圳市气候资料(来源:深圳市气象局) (in Chinese). Shenzhen Meteorological Bureau. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ↑ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ↑ 中华人民共和国县以上行政区划代码. Ministry of Civil Affairs.

- ↑ 深圳市统计局. 《深圳统计年鉴2014》. China Statistics Print (中国统计出版社). Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ "Shenzhen government official/深圳政府在线". Retrieved Sep 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Official PRC announcement". gov.cn. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ↑ 二线关景观改造方案出炉 涉及8个主要的二线关口 [The plans for the ErXianGuan landscape reconstruction have been announced, involving 8 major former border passages]. 深圳本地宝 (sz.bendibao.com). 2 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ Copyright@中国时刻网、深圳广播电影电视集团. "Archived copy" 政协论坛 二线关:将说真正的再见(下) 2015-11-29_政协论坛_电视_CUTV深圳台. sztv.CUTV.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ 二线关将说真正的再见 检查站物理设施将全部清除. www.sznews.com. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ "Shenzhen to remove outdated boundary around economic zone - Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2018-01-16.

- ↑ 国务院关于同意撤销深圳经济特区管理线的批复(国函〔2018〕3号)_政府信息公开专栏. www.gov.cn. Retrieved 2018-01-16.

- ↑ 深圳规划合并关内关外取消区级政府. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Expect-the-Unexpected—Bettys-Story&id=6820539

- ↑ "Age Composition and Dependency Ratio of Population by Region (2004)". China Statistics 2005. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Shenzhen Government Online, Citizens' Life (Recovered from the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Shenzhen Daily 13 June 2007

- ↑ "Cross-border Commuters Live Hard between Hong Kong and Shenzhen | Feed Magazine - HKBU MA International Journalism Student Stories". journalism.hkbu.edu.hk. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- ↑ "广东省公安厅出入境政务服务网". www.gdcrj.com. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- ↑ CNBC.com, Justina Crabtree; special to (20 September 2016). "A tale of megacities: China's largest metropolises". CNBC.

slide 2

- ↑ "深圳客家人的來歷和客家民居 Hakka Origins and Settlements in Shenzhen". 中國國際廣播電臺國際線上. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "圍頭話 Weitou dialect". Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ Rule, Ted and Karen, Shenzhen the Book Hong Kong 2014

- ↑ 張 ZHANG, 則武 Zewu. "浅谈深圳城中村的成因及其影响 A Discussion concerning the History and Consequences of Urban Villages in Shenzhen". Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ 秦 CHUN, 炳煜 Bing Yuk (7 July 2006). "深圳成粵語圈中普通話區 Shenzhen becomes the Mandarin area in a Cantonese region". 文匯報 Wenweipo. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "深圳將粵語精髓融入普通話 Shenzhen Incorporates Cantonese Essence into Mandarin". 南方網. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "中华人民共和国国家通用语言文字法 The National Lingua Franca and Orthography Act-- People's Republic of China". Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ He, Huifeng. "Trendy Shenzhen teenagers spearhead Cantonese revival". South China Morning Post. South China Morning Post. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- 1 2 Demographics of religion in Shenzhen (archived) for the "6 under 60" research project by the University of Southern California. See also Lani Heidecker's data for the Shenzhen Geography Project (archived).

- ↑ "中共深圳市委统战部(市民族宗教事务局、市侨务办公室、市侨联)". www.tzb.sz.gov.cn. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ Fan, Lizhu; Whitehead, James D. (2011). "Spirituality in a Modern Chinese Metropolis". In Palmer, David A.; Shive, Glenn; Wickeri, Philip L. Chinese Religious Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199731381

- ↑ Fan, Lizhu; Whitehead, James D. (2013). "Fate and Fortune: Popular Religion and Moral Capital in Shenzhen". Journal of Chinese Religions, 32. pp. 83–100.

- ↑ Payette, Alex. "Shenzhen's Kongshengtang: Religious Confucianism and Local Moral Governance". Role of Religion in Political Life, Panel RC43, 23rd World Congress of Political Science, 19–24 July 2014.

- ↑ Wei Ge (1999). "Chapter 4: The Performance of Special Economic Zones". Special Economic Zones and the Economic Transition in China. World Scientific Publishing Co Pte Ltd. pp. 67–108. ISBN 978-9810237905.

- ↑ Yeandle, Mark. "GFCI 19 The Overall Rankings". www.longfinance.net. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ "The Global Financial Centres Index 21" (PDF). Long Finance. March 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-11.

- ↑ "# of +200m Buildings". CTBUH. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- ↑ "Contact us Archived 26 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.." Huawei. Retrieved on 4 February 2009.

- ↑ "Guangdong - Shenzhen High-tech Industrial Park". Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ "". Retrieved on 5 July 2014.

- ↑ Chaney, Joseph (15 June 2015). "Shenzhen: China's start-up city defies skeptics". CNN.

- ↑ "HAX Accelerator". Official website of HAX. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ "Shenzhen Software Park". Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ "SZSE Overview". Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ "one-stop portal of the Hong Kong SAR Government / 香港政府一站通". GovHK. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ↑ "深圳九大口岸通关攻略". Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- 1 2 HKG Monthly Digest of Statistics

- ↑ HKG Traffic and Transport Digest

- ↑ HKG Cross Boundary Survey 2004

- ↑ HKG Shipping Statistics

- ↑ HKG Trade and Industry Statistics

- 1 2 "Hong Kong International Airport – Your Regional Hub with Worldwide Connections and Gateway to China". Hongkongairport.com. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ↑ HKG Cross Boundary Survey 1999 & 2003

- 1 2 Fung, Anita. "Qianhai Taking RMB Internationalisation to the Next Level". New Zealand China Trade Association. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ↑ Tse, Constant. "State Council Approves Preferential Policies for Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone". Deloitte. 169.

- ↑ "Ping An Finance Center - The Skyscraper Center". www.SkyscraperCenter.com. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ "KK100 – The Skyscraper Center". CTBUH. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ "Shun Hing Square (Diwang/Di Wang Commercial Center)". Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ 深圳摩天大楼列表,深圳第一高楼. top.gaoloumi.com. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ "SEG Plaza – The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012.

- ↑ 深圳30年:深圳国贸大厦. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Robinson, Melia (17 January 2017). "One Chinese city built more skyscrapers in 2016 than the US and Australia combined". Business Insider. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ 深圳“红绿的”5日起统一收费(图)--部门动态. www.sz.gov.cn (in Chinese). Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- ↑ 香港九龙机铁站往深圳机场 [Airport Railway Kowloon Station to Shenzhen Airport] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

香港九龍機鐵站往深圳機場 (全程行車時間:車程約75分鐘) Kowloon, Hong Kong Airport Railway Station to Shenzhen Airport (journey time: about 75 minutes by car)

- ↑ "Shenzhen imposes limits on purchases of new cars".

- ↑ "[SZ] Cruise terminal operational in Nov". Guangdong news. 17 August 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ "Top 50 container ports in the world". www.worldshipping.org. World shipping council / Journal of commerce. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ "深圳港港口介绍". Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ "Contact Us." Shenzhen Airlines. Retrieved on 9 September 2009.

- ↑ "Contact Us Archived 11 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine.." Jade Cargo International. Retrieved on 11 July 2010.

- ↑ "UPS Launches Shenzhen Flights". Ups.com. 8 February 2010. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011.

- ↑ "联系我们 Archived 4 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine.." Shenzhen Donghai Airlines. Retrieved on 24 February 2014. "Address:Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport, Shenzhen Airlines. Post code:518128" – Chinese address: "地址:深圳市宝安区宝安国际机场航站四路3009号东海航空基地 邮政编码:518128"

- ↑ "Contact Us." SF Airlines. Retrieved on 24 February 2014. "SF Airlines Co., Ltd. Address: No.1 Freight Depot, International Shipping Center of Bao'an International Airport, Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, 518128, P.R.C." – Chinese address: "地 址:中国广东省深圳市宝安国际机场国际货运中心1号货站 邮 编:518128"

- ↑ "Ferry Transfer." Hong Kong International Airport. Retrieved on May 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Mainland Coaches." Hong Kong International Airport. Retrieved on May 8, 2018.

- ↑ Shenzhen New Railway Station to Be Built, Shortens Trip to Guangzhou Archived 11 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 宗传苓,谭国威,张晓春.基于城市发展战略的深圳高铁枢纽规划研究——以深圳北站和福田站为例[J].规划师,2011,27(10);23–29.

- ↑ 广州深圳升级为半小时城市圈. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ "Buji Station renamed Shenzhen East ---szdaily多媒体数字报刊平台". Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ "More ticket counters at Hong Kong terminus of high-speed rail link after chaotic first day marked by queues and ticket confusion". South China Morning Post. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ "High-speed rail set to bring bumper 'Golden Week' for Hong Kong tourism as mainland Chinese visitors snap up tickets for first day". South China Morning Post. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ "City to spend 48b yuan on 3 Metro lines". Shenzhen Daily. Archived from the original on 15 July 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Shenzhen Metro". exploremetro. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ 深圳市统计局 (2 December 2008). "Archived copy" 深圳市2011年国民经济和社会发展统计公报. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ "深圳地铁7、9、11号线2016年底开通". Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ↑ "Shenzhen Shekou Passenger Terminal". szgky.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ "2013年最新深圳福永码头时刻表-深圳福永码头去澳门-深圳福永码头到香港-福永口岸通关时间_深圳指南_深圳热线". life.szonline.net. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ The City Parks of Shenzhen The City Parks of Shenzhen ~ Retrieved 2 February 2010

- ↑ "Buzz on the waterfront". TTGmice. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ↑ "About us". Szseaworld.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ↑ Daily, Shekou. "Free Entry to the NEW Maritime Museum in Shekou Shenzhen". ShekouDaily.cn. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ Daily, Shekou. "ShekouDaily: Bringing you the best of Shekou, Sea World, Shenzhen, China". ShekouDaily.com. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ The Official website of the 2019 FIBA Basketball World Cup, FIBA.com, Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ↑ 球队简介——深圳红钻队 at sports.163.com. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2013

- ↑ "健力宝俱乐部欠债累累 中超冠军欲"借钱"过年". sports.sina.com.cn. 26 November 2004. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ↑ 硕, 陈 (17 July 2014). "深圳红钻欠薪曝光合计约700万 中国足协介入调查". Xinhuanet. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ↑ "2011 Summer Universiade". International University Sports Federation. Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ Universiade 2011 Shenzhen Archived 18 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Photos construction stadiums Universiade Shenzhen

- ↑ "China's Skateboarding Revolution". 20 May 2015.

- ↑ "HSSCA". HSSCA. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- ↑ Nürnberg International - Informationen zu den Auslandsbeziehungen der Stadt Nürnberg

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shenzhen. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Shenzhen. |