Peripheral neuropathy

| Peripheral neuropathy | |

|---|---|

| |

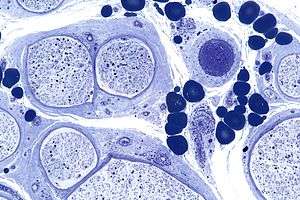

| Micrograph showing a vasculitic peripheral neuropathy; plastic embedded; Toluidine blue stain | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Peripheral neuropathy (PN) is damage to or disease affecting nerves, which may impair sensation, movement, gland or organ function, or other aspects of health, depending on the type of nerve affected. Common causes include systemic diseases (such as diabetes or leprosy), hyperglycemia-induced glycation,[1][2][3] vitamin deficiency, medication (e.g., chemotherapy, or commonly prescribed antibiotics including metronidazole and the fluoroquinolone class of antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin, Levaquin, Avelox etc.)), traumatic injury, including ischemia, radiation therapy, excessive alcohol consumption, immune system disease, coeliac disease, or viral infection. It can also be genetic (present from birth) or idiopathic (no known cause).[4][5][6] In conventional medical usage, the word neuropathy (neuro-, "nervous system" and -pathy, "disease of")[7] without modifier usually means peripheral neuropathy.

Neuropathy affecting just one nerve is called "mononeuropathy" and neuropathy involving nerves in roughly the same areas on both sides of the body is called "symmetrical polyneuropathy" or simply "polyneuropathy". When two or more (typically just a few, but sometimes many) separate nerves in disparate areas of the body are affected it is called "mononeuritis multiplex", "multifocal mononeuropathy", or "multiple mononeuropathy".[4][5][6]

Peripheral neuropathy may be chronic (a long-term condition where symptoms begin subtly and progress slowly) or acute (sudden onset, rapid progress, and slow resolution). Acute neuropathies demand urgent diagnosis. Motor nerves (that control muscles), sensory nerves, or autonomic nerves (that control automatic functions such as heart rate, body temperature, and breathing) may be affected. More than one type of nerve may be affected at the same time. Peripheral neuropathies may be classified according to the type of nerve predominantly involved, or by the underlying cause.[4][5][6]

Neuropathy may cause painful cramps, fasciculations (fine muscle twitching), muscle loss, bone degeneration, and changes in the skin, hair, and nails. Additionally, motor neuropathy may cause impaired balance and coordination or, most commonly, muscle weakness; sensory neuropathy may cause numbness to touch and vibration, reduced position sense causing poorer coordination and balance, reduced sensitivity to temperature change and pain, spontaneous tingling or burning pain, or skin allodynia (severe pain from normally nonpainful stimuli, such as light touch); and autonomic neuropathy may produce diverse symptoms, depending on the affected glands and organs, but common symptoms are poor bladder control, abnormal blood pressure or heart rate, and reduced ability to sweat normally.[4][5][6]

Classification

Peripheral neuropathy may be classified according to the number and distribution of nerves affected (mononeuropathy, mononeuritis multiplex, or polyneuropathy), the type of nerve fiber predominantly affected (motor, sensory, autonomic), or the process affecting the nerves; e.g., inflammation (neuritis), compression (compression neuropathy), chemotherapy (chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy).

Mononeuropathy

Mononeuropathy is a type of neuropathy that only affects a single nerve.[8] Diagnostically, it is important to distinguish it from polyneuropathy because when a single nerve is affected, it is more likely to be due to localized trauma or infection.

The most common cause of mononeuropathy is physical compression of the nerve, known as compression neuropathy. Carpal tunnel syndrome and axillary nerve palsy are examples. Direct injury to a nerve, interruption of its blood supply resulting in (ischemia), or inflammation also may cause mononeuropathy.

Polyneuropathy

"Polyneuropathy" is a pattern of nerve damage that is quite different from mononeuropathy, often more serious and affecting more areas of the body. The term "peripheral neuropathy" sometimes is used loosely to refer to polyneuropathy. In cases of polyneuropathy, many nerve cells in various parts of the body are affected, without regard to the nerve through which they pass; not all nerve cells are affected in any particular case. In distal axonopathy, one common pattern is that the cell bodies of neurons remain intact, but the axons are affected in proportion to their length; the longest axons are the most affected. Diabetic neuropathy is the most common cause of this pattern. In demyelinating polyneuropathies, the myelin sheath around axons is damaged, which affects the ability of the axons to conduct electrical impulses. The third and least common pattern affects the cell bodies of neurons directly. This usually picks out either the motor neurons (known as motor neuron disease) or the sensory neurons (known as sensory neuronopathy or dorsal root ganglionopathy).

The effect of this is to cause symptoms in more than one part of the body, often symmetrically on left and right sides. As for any neuropathy, the chief symptoms include motor symptoms such as weakness or clumsiness of movement; and sensory symptoms such as unusual or unpleasant sensations such as tingling or burning; reduced ability to feel sensations such as texture or temperature, and impaired balance when standing or walking. In many polyneuropathies, these symptoms occur first and most severely in the feet. Autonomic symptoms also may occur, such as dizziness on standing up, erectile dysfunction, and difficulty controlling urination.

Polyneuropathies usually are caused by processes that affect the body as a whole. Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance are the most common causes. Hyperglycemia-induced formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) is related to diabetic neuropathy.[9] Other causes relate to the particular type of polyneuropathy, and there are many different causes of each type, including inflammatory diseases such as Lyme disease, vitamin deficiencies, blood disorders, and toxins (including alcohol and certain prescribed drugs).

Most types of polyneuropathy progress fairly slowly, over months or years, but rapidly progressive polyneuropathy also occurs. It is important to recognize that at one time it was thought that many of the cases of small fiber peripheral neuropathy with typical symptoms of tingling, pain, and loss of sensation in the feet and hands were due to glucose intolerance before a diagnosis of diabetes or pre-diabetes. However, in August 2015, the Mayo Clinic published a scientific study in the Journal of the Neurological Sciences showing "no significant increase in...symptoms...in the prediabetes group", and stated that "A search for alternate neuropathy causes is needed in patients with prediabetes." [10]

The treatment of polyneuropathies is aimed firstly at eliminating or controlling the cause, secondly at maintaining muscle strength and physical function, and thirdly at controlling symptoms such as neuropathic pain.

Mononeuritis multiplex

Mononeuritis multiplex, occasionally termed polyneuritis multiplex, is simultaneous or sequential involvement of individual noncontiguous nerve trunks,[11] either partially or completely, evolving over days to years and typically presenting with acute or subacute loss of sensory and motor function of individual nerves. The pattern of involvement is asymmetric, however, as the disease progresses, deficit(s) becomes more confluent and symmetrical, making it difficult to differentiate from polyneuropathy.[12] Therefore, attention to the pattern of early symptoms is important.

Mononeuritis multiplex also may cause pain, which is characterized as deep, aching pain that is worse at night and frequently in the lower back, hip, or leg. In people with diabetes mellitus, mononeuritis multiplex typically is encountered as acute, unilateral, and severe thigh pain followed by anterior muscle weakness and loss of knee reflex.

Electrodiagnostic medicine studies will show multifocal sensory motor axonal neuropathy.

It is caused by, or associated with, several medical conditions:

- diabetes mellitus

- vasculitides: polyarteritis nodosa,[13][14] granulomatosis with polyangiitis[14] and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis[14]

- immune-mediated diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis,[15] systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- infections: leprosy, lyme disease, Parvovirus B19,[16] HIV[17]

- sarcoidosis[18]

- cryoglobulinemia[19]

- reactions to exposure to chemical agents, including trichloroethylene and dapsone

- rarely, following the sting of certain jellyfish, such as the sea nettle

Autonomic neuropathy

Autonomic neuropathy is a form of polyneuropathy that affects the non-voluntary, non-sensory nervous system (i.e., the autonomic nervous system), affecting mostly the internal organs such as the bladder muscles, the cardiovascular system, the digestive tract, and the genital organs. These nerves are not under a person's conscious control and function automatically. Autonomic nerve fibers form large collections in the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis outside the spinal cord. They have connections with the spinal cord and ultimately the brain, however. Most commonly autonomic neuropathy is seen in persons with long-standing diabetes mellitus type 1 and 2. In most—but not all—cases, autonomic neuropathy occurs alongside other forms of neuropathy, such as sensory neuropathy.

Autonomic neuropathy is one cause of malfunction of the autonomic nervous system, but not the only one; some conditions affecting the brain or spinal cord also may cause autonomic dysfunction, such as multiple system atrophy, and therefore, may cause similar symptoms to autonomic neuropathy.

The signs and symptoms of autonomic neuropathy include the following:

- Urinary bladder conditions: bladder incontinence or urine retention

- Gastrointestinal tract: dysphagia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, malabsorption, fecal incontinence, gastroparesis, diarrhoea, constipation

- Cardiovascular system: disturbances of heart rate (tachycardia, bradycardia), orthostatic hypotension, inadequate increase of heart rate on exertion

- Respiratory system: impairments in the signals associated with regulation of breathing and gas exchange (central sleep apnea, hypopnea, bradypnea).[20]

- Other areas: hypoglycemia unawareness, genital impotence, sweat disturbances

Neuritis

Neuritis is a general term for inflammation of a nerve[21] or the general inflammation of the peripheral nervous system. Symptoms depend on the nerves involved, but may include pain, paresthesia (pins-and-needles), paresis (weakness), hypoesthesia (numbness), anesthesia, paralysis, wasting, and disappearance of the reflexes.

Causes of neuritis include:

- Physical injury

- Infection

- Diphtheria

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Leprosy

- Lyme disease

- Chemical injury such as chemotherapy

- Radiation therapy

Types of neuritis include:

- Brachial neuritis

- Cranial neuritis such as Bell's palsy

- Optic neuritis

- Vestibular neuritis

- Wartenberg's migratory sensory neuropathy

- Underlying conditions including: :

- Alcoholism

- Autoimmune disease, especially multiple sclerosis and Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Beriberi (vitamin B1 deficiency)

- Cancer

- Celiac disease[22]

- Diabetes mellitus (Diabetic neuropathy)

- Hypothyroidism

- Porphyria

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Vitamin B6 excess[23]

Signs and symptoms

Those with diseases or dysfunctions of their nerves may present with problems in any of the normal nerve functions. Symptoms vary depending on the types of nerve fiber involved. In terms of sensory function, symptoms commonly include loss of function ("negative") symptoms, including numbness, tremor, impairment of balance, and gait abnormality.[24] Gain of function (positive) symptoms include tingling, pain, itching, crawling, and pins-and-needles. Motor symptoms include loss of function ("negative") symptoms of weakness, tiredness, muscle atrophy, and gait abnormalities; and gain of function ("positive") symptoms of cramps, and muscle twitch (fasciculations).[25]

In the most common form, length-dependent peripheral neuropathy, pain and parasthesia appears symmetrically and generally at the terminals of the longest nerves, which are in the lower legs and feet. Sensory symptoms generally develop before motor symptoms such as weakness. Length-dependent peripheral neuropathy symptoms make a slow ascent of leg, while symptoms may never appear in the upper limbs; if they do, it will be around the time that leg symptoms reach the knee.[26] When the nerves of the autonomic nervous system are affected, symptoms may include constipation, dry mouth, difficulty urinating, and dizziness when standing.[25]

Causes

The causes are grouped broadly as follows:

- Genetic diseases: Friedreich's ataxia, Fabry disease,[27] Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease,[28] hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsy

- hyperglycemia-induced formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs)[9][29][30]

- Metabolic and endocrine diseases: diabetes mellitus,[27] chronic kidney failure, porphyria, amyloidosis, liver failure, hypothyroidism

- Toxic causes: drugs (vincristine, metronidazole, phenytoin, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid, ethyl alcohol, statins[31][32]), organic herbicides TCDD dioxin, organic metals, heavy metals, excess intake of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine). Peripheral neuropathies also may result from long term (more than 21 days) treatment with Linezolid (Zyvox).

- Adverse effects of fluoroquinolones: irreversible neuropathy is a serious adverse reaction of fluoroquinolone drugs[33]

- Inflammatory diseases: Guillain–Barré syndrome,[27] systemic lupus erythematosus, leprosy, multiple sclerosis,[27] Sjögren's syndrome, Babesiosis, Lyme disease,[27] vasculitis,[27] sarcoidosis,[34]

- Vitamin deficiency states: Vitamin B12 (Methylcobalamin),[27] vitamin A, vitamin E, vitamin B1 (thiamin)

- Physical trauma: compression, pinching, cutting, projectile injuries (for example, gunshot wound), strokes including prolonged occlusion of blood flow, electric discharge, including lightning strikes

- Effect of chemotherapy – see Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy[27]

- Exposure to Agent Orange[35]

- Others: electric shock, HIV,[27][36] malignant disease, radiation, shingles, MGUS (Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance).[37]

Diagnosis

Peripheral neuropathy may first be considered when an individual reports symptoms of numbness, tingling, and pain in feet. After ruling out a lesion in the central nervous system as a cause, diagnosis may be made on the basis of symptoms, laboratory and additional testing, clinical history, and a detailed examination.

During physical examination, specifically a neurological examination, those with generalized peripheral neuropathies most commonly have distal sensory or motor and sensory loss, although those with a pathology (problem) of the nerves may be perfectly normal; may show proximal weakness, as in some inflammatory neuropathies, such as Guillain–Barré syndrome; or may show focal sensory disturbance or weakness, such as in mononeuropathies. Classically, ankle jerk reflex is absent in peripheral neuropathy.

A physical examination will involve testing the deep ankle reflex as well as examining the feet for any ulceration. For large fiber neuropathy, an exam will usually show an abnormally decreased sensation to vibration, which is tested with a 128-Hz tuning fork, and decreased sensation of light touch when touched by a nylon monofilament.[26]

Diagnostic tests include electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCSs), which assess large myelinated nerve fibers.[26] Testing for small-fiber peripheral neuropathies often relates to the autonomic nervous system function of small thinly- and unmyelinated fibers. These tests include a sweat test and a tilt table test. Diagnosis of small fiber involvement in peripheral neuropathy may also involve a skin biopsy in which a 3 mm-thick section of skin is removed from the calf by a punch biopsy, and is used to measure the skin intraepidermal nerve fiber density (IENFD), the density of nerves in the outer layer of the skin.[24] Reduced density of the small nerves in the epidermis supports a diagnosis of small-fiber peripheral neuropathy.

Laboratory tests include blood tests for vitamin B-12 levels, a complete blood count, measurement of thyroid stimulating hormone levels, a comprehensive metabolic panel screening for diabetes and pre-diabetes, and a serum immunofixation test, which tests for antibodies in the blood.[25]

Treatment

The treatment of peripheral neuropathy varies based on the cause of the condition, and treating the underlying condition can aid in the management of neuropathy. When peripheral neuropathy results from diabetes mellitus or prediabetes, blood sugar management is key to treatment. In prediabetes in particular, strict blood sugar control can significantly alter the course of neuropathy.[24] In peripheral neuropathy that stems from immune-mediated diseases, the underlying condition is treated with intravenous immunoglobulin or steroids. When peripheral neuropathy results from vitamin deficiencies or other disorders, those are treated as well.[24]

Medications

A range of medications that act on the central nervous system has been found to be useful in managing neuropathic pain. Commonly used treatments include tricyclic antidepressants (such as nortriptyline or amitriptyline), the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) medication duloxetine, and antiepileptic therapies such as gabapentin, pregabalin, or sodium valproate. Few studies have examined whether nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are effective in treating peripheral neuropathy.[38]

Symptomatic relief for the pain of peripheral neuropathy may be obtained by application of topical capsaicin. Capsaicin is the factor that causes heat in chili peppers. The evidence suggesting that capsaicin applied to the skin reduces pain for peripheral neuropathy is of moderate to low quality and should be interpreted carefully before using this treatment option.[39] Local anesthesia often is used to counteract the initial discomfort of the capsaicin. Some current research in animal models has shown that depleting neurotrophin-3 may oppose the demyelination present in some peripheral neuropathies by increasing myelin formation.[40]

Evidence supports the use of cannabinoids for some forms of neuropathic pain.[41]

Medical devices

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation therapy may be effective and safe in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. A recent review of three trials involving 78 patients found some improvement in pain scores after 4 and 6, but not 12 weeks of treatment and an overall improvement in neuropathic symptoms at 12 weeks.[42] Another review of four trials found significant improvement in pain and overall symptoms, with 38% of patients in one trial becoming asymptomatic. The treatment remains effective even after prolonged use, but symptoms return to baseline within a month of cessation of treatment.[43]

Research

A 2008 literature review concluded that, "based on principles of evidence-based medicine and evaluations of methodology, there is only a 'possible' association [of celiac disease and peripheral neuropathy], due to lower levels of evidence and conflicting evidence. There is not yet convincing evidence of causality."[44]

See also

References

- ↑ Sugimoto K, Yasujima M, Yagihashi S (2008). "Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic neuropathy". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 14 (10): 953–61. doi:10.2174/138161208784139774. PMID 18473845.

- ↑ Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS (February 2014). "Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications". The Korean Journal of Physiology & Pharmacology. 18 (1): 1–14. doi:10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.1.1. PMC 3951818. PMID 24634591.

- ↑ Jack M, Wright D (May 2012). "Role of advanced glycation endproducts and glyoxalase I in diabetic peripheral sensory neuropathy". Translational Research. 159 (5): 355–65. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2011.12.004. PMC 3329218. PMID 22500508.

- 1 2 3 4 Richard A C Hughes (23 February 2002). "Clinical review: Peripheral neuropathy". British Medical Journal. 324 (7335): 466–469. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7335.466.

- 1 2 3 4 Torpy JM, Kincaid JL, Glass RM (April 2010). "JAMA patient page. Peripheral neuropathy". JAMA. 303 (15): 1556. doi:10.1001/jama.303.15.1556. PMID 20407067.

- 1 2 3 4 "Peripheral neuropathy fact sheet". National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 19 September 2012.

- ↑ "neuropathy". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:mononeuropathy".

- 1 2 Sugimoto K, Yasujima M, Yagihashi S (2008). "Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic neuropathy". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 14 (10): 953–61. doi:10.2174/138161208784139774. PMID 18473845.

- ↑ Kassardjian CD, Dyck PJ, Davies JL, Carter RE, Dyck PJ (August 2015). "Does prediabetes cause small fiber sensory polyneuropathy? Does it matter?". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 355 (1–2): 196–8. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.05.026. PMC 4621009. PMID 26049659.

- ↑ Campellone JV. "Mononeuritis multiplex". MedlinePlus. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Ball DA. "Peripheral Neuropathy". NeuraVite. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Criado PR, Marques GF, Morita TC, de Carvalho JF (June 2016). "Epidemiological, clinical and laboratory profiles of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa patients: Report of 22 cases and literature review". Autoimmunity Reviews. 15 (6): 558–63. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2016.02.010. PMID 26876385.

- 1 2 3 Samson M, Puéchal X, Devilliers H, Ribi C, Cohen P, Bienvenu B, Terrier B, Pagnoux C, Mouthon L, Guillevin L (September 2014). "Mononeuritis multiplex predicts the need for immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory drugs for EGPA, PAN and MPA patients without poor-prognosis factors". Autoimmunity Reviews. 13 (9): 945–53. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.08.002. PMID 25153486.

- ↑ Hellmann DB, Laing TJ, Petri M, Whiting-O'Keefe Q, Parry GJ (1988). "Mononeuritis multiplex: the yield of evaluations for occult rheumatic diseases". Medicine. 67 (3): 145–53. doi:10.1097/00005792-198805000-00001. PMID 2835572.

- ↑ Lenglet T, Haroche J, Schnuriger A, Maisonobe T, Viala K, Michel Y, Chelbi F, Grabli D, Seror P, Garbarg-Chenon A, Amoura Z, Bouche P (July 2011). "Mononeuropathy multiplex associated with acute parvovirus B19 infection: characteristics, treatment and outcome". Journal of Neurology. 258 (7): 1321–6. doi:10.1007/s00415-011-5931-2. PMID 21287183.

- ↑ Kaku M, Simpson DM (November 2014). "HIV neuropathy". Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 9 (6): 521–6. doi:10.1097/COH.0000000000000103. PMID 25275705.

- ↑ Vargas DL, Stern BJ (August 2010). "Neurosarcoidosis: diagnosis and management". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 31 (4): 419–27. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1262210. PMID 20665392.

- ↑ Cacoub P, Comarmond C, Domont F, Savey L, Saadoun D (September 2015). "Cryoglobulinemia Vasculitis". The American Journal of Medicine. 128 (9): 950–5. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.02.017. PMID 25837517.

- ↑ Vinik AI, Erbas T (2013). "Diabetic autonomic neuropathy". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 117: 279–94. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-53491-0.00022-5. ISBN 9780444534910. PMID 24095132.

- ↑ "neuritis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Chin RL, Latov N (January 2005). "Peripheral Neuropathy and Celiac Disease". Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 7 (1): 43–48. doi:10.1007/s11940-005-0005-3. PMID 15610706.

- ↑ Rosenbloom M, Tarabar A, Adler RA. "Vitamin Toxicity". Medscape Reference. Medscape. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Cioroiu CM, Brannagan TH (2014). "Peripheral Neuropathy". Current Geriatrics Reports. 3 (2): 83–90. doi:10.1007/s13670-014-0079-4.

- 1 2 3 Azhary H, Farooq MU, Bhanushali M, Majid A, Kassab MY (April 2010). "Peripheral neuropathy: differential diagnosis and management". American Family Physician. 81 (7): 887–92. PMID 20353146.

- 1 2 3 Watson JC, Dyck PJ (July 2015). "Peripheral Neuropathy: A Practical Approach to Diagnosis and Symptom Management". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (7): 940–51. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.05.004. PMID 26141332.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Gilron I, Baron R, Jensen T (April 2015). "Neuropathic pain: principles of diagnosis and treatment". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (4): 532–45. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.01.018. PMID 25841257.

- ↑ Gabriel JM, Erne B, Pareyson D, Sghirlanzoni A, Taroni F, Steck AJ (December 1997). "Gene dosage effects in hereditary peripheral neuropathy. Expression of peripheral myelin protein 22 in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A and hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies nerve biopsies". Neurology. 49 (6): 1635–40. doi:10.1212/WNL.49.6.1635. PMID 9409359.

- ↑ Hayreh SS, Servais GE, Virdi PS (January 1986). "Fundus lesions in malignant hypertension. V. Hypertensive optic neuropathy". Ophthalmology. 93 (1): 74–87. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33773-4. PMID 3951818. /

- ↑ Kawana T, Yamamoto H, Izumi H (December 1987). "A case of aspergillosis of the maxillary sinus". The Journal of Nihon University School of Dentistry. 29 (4): 298–302. doi:10.2334/josnusd1959.29.298. PMID 3329218.

- ↑ "Statin Drugs May Increase Risk Of Peripheral Neuropathy". ScienceDaily. St. Paul, Minnesota. 15 May 2002. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ "Statin Drugs May Increase Risk of Peripheral Neuropathy". AAN.com (Press release). St. Paul, Minnesota: American Academy of Neurology. 13 May 2002. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Cohen JS (December 2001). "Peripheral neuropathy associated with fluoroquinolones" (PDF). The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 35 (12): 1540–7. doi:10.1345/aph.1Z429. PMID 11793615.

- ↑ Heck AW, Phillips LH (August 1989). "Sarcoidosis and the nervous system". Neurologic Clinics. 7 (3): 641–54. PMID 2671639.

- ↑ "Service-Connected Disability Compensation For Exposure To Agent Orange" (PDF). Vietnam Veterans of America. April 2015. p. 4. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Gonzalez-Duarte A, Cikurel K, Simpson DM (August 2007). "Managing HIV peripheral neuropathy". Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 4 (3): 114–8. doi:10.1007/s11904-007-0017-6. PMID 17883996.

- ↑ Nobile-Orazio E, Barbieri S, Baldini L, Marmiroli P, Carpo M, Premoselli S, Manfredini E, Scarlato G (June 1992). "Peripheral neuropathy in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance: prevalence and immunopathogenetic studies". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 85 (6): 383–90. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb06033.x. PMID 1379409.

- ↑ Moore RA, Chi CC, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Rice AS (October 2015). "Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for neuropathic pain". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD010902. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010902.pub2. PMID 26436601.

- ↑ Derry S, Rice AS, Cole P, Tan T, Moore RA (January 2017). "Topical capsaicin (high concentration) for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD007393. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007393.pub4. PMID 28085183.

- ↑ Liu N, Varma S, Tsao D, Shooter EM, Tolwani RJ (October 2007). "Depleting endogenous neurotrophin-3 enhances myelin formation in the Trembler-J mouse, a model of a peripheral neuropathy". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 85 (13): 2863–9. doi:10.1002/jnr.21388. PMID 17628499.

- ↑ Hill KP (June 2015). "Medical Marijuana for Treatment of Chronic Pain and Other Medical and Psychiatric Problems: A Clinical Review". JAMA. 313 (24): 2474–83. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6199. PMID 26103031.

Use of marijuana for chronic pain, neuropathic pain, and spasticity due to multiple sclerosis is supported by high-quality evidence

- ↑ Jin DM, Xu Y, Geng DF, Yan TB (July 2010). "Effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on symptomatic diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 89 (1): 10–5. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.021. PMID 20510476.

- ↑ Pieber K, Herceg M, Paternostro-Sluga T (April 2010). "Electrotherapy for the treatment of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a review". Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 42 (4): 289–95. doi:10.2340/16501977-0554. PMID 20461329.

- ↑ Grossman G (April 2008). "Neurological complications of coeliac disease: what is the evidence?". Pract Neurol. 8 (2): 77–89. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.139717. PMID 18344378.

Further reading

- Latov N (2007). Peripheral Neuropathy: When the Numbness, Weakness, and Pain Won't Stop. New York: American Academy of Neurology Press Demos Medical. ISBN 1-932603-59-X.

- "Practice advisory for the prevention of perioperative peripheral neuropathies: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Prevention of Perioperative Peripheral Neuropathies". Anesthesiology. 92 (4): 1168–82. April 2000. doi:10.1097/00000542-200004000-00036. PMID 10754638.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Peripheral Neuropathy from the US NIH

- Neuropathy: Causes, Symptoms and Treatments from Medical News Today

- Peripheral Neuropathy at the Mayo Clinic