Epileptic seizure

| Epileptic seizure | |

|---|---|

| Synonym | Epileptic fit,[1] seizure, fit |

| |

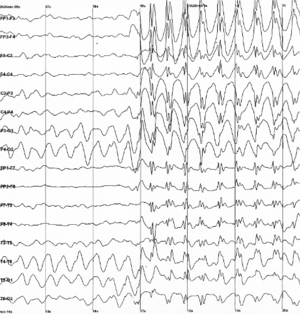

| Generalized 3 Hz spike and wave discharges in EEG | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Differential diagnosis | Syncope, nonepileptic psychogenic seizure, tremor[2] |

A seizure, technically known as an epileptic seizure, is a brief episode of signs or symptoms due to abnormally excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.[3] The outward effect can vary from uncontrolled jerking movement (tonic-clonic seizure) to as subtle as a momentary loss of awareness (absence seizure). Diseases of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures are collectively called epilepsy.[3][4]

Seizures can also occur in people who do not have epilepsy for various reasons including brain trauma, drug use, elevated body temperature, low blood sugar and low levels of oxygen. Additionally, there are a number of conditions that look like epileptic seizures but are not.

A seizure is a medical emergency.[5] A first seizure generally does not require long term treatment with anti-seizure medications unless there is a specific problem on either electroencephalogram or brain imaging.[6]

5–10% of people who live to 80 years old have at least one epileptic seizure[6] and the chance of experiencing a second seizure is between 40% and 50%.[7] About 50% of patients with an unprovoked apparent "first seizure" have had other minor seizures, so their diagnosis is epilepsy.[8] Epilepsy affects about 1% of the population currently[9] and affected about 4% of the population at some point in time.[6] Most of those affected—nearly 80%—live in developing countries.[9]

Signs and symptoms

The signs and symptoms of seizures vary depending on the type.[10] The most common type of seizure is convulsive (60%).[11] Two-thirds of these begin as focal seizures and become generalized while one third begin as generalized seizures.[11] The remaining 40% of seizures are non-convulsive, an example of which is absence seizure.[12]

Focal seizures

Focal seizures are often preceded by certain experiences, known as an aura.[10] These may include sensory, visual, psychic, autonomic, olfactory or motor phenomena.[13]

In a complex partial seizure a person may appear confused or dazed and can not respond to questions or direction. Focal seizure may become generalized.[13]

Jerking activity may start in a specific muscle group and spread to surrounding muscle groups—known as a Jacksonian march.[14] Unusual activities that are not consciously created may occur.[14] These are known as automatisms and include simple activities like smacking of the lips or more complex activities such as attempts to pick something up.[14]

Generalized seizures

There are six main types of generalized seizures: tonic-clonic, tonic, clonic, myoclonic, absence, and atonic seizures.[15] They all involve a loss of consciousness and typically happen without warning.[16]

- Tonic-clonic seizures present with a contraction of the limbs followed by their extension, along with arching of the back for 10–30 seconds.[16] A cry may be heard due to contraction of the chest muscles.[16] The limbs then begin to shake in unison.[16] After the shaking has stopped it may take 10–30 minutes for the person to return to normal.[16]

- Tonic seizures produce constant contractions of the muscles.[16] The person may turn blue if breathing is impaired.[16]

- Clonic seizures involve shaking of the limbs in unison.[16]

- Myoclonic seizures involve spasms of muscles in either a few areas or generalized through the body.[16]

- Absence seizures can be subtle, with only a slight turn of the head or eye blinking.[13] The person often does not fall over and may return to normal right after the seizure ends, though there may also be a period of post-ictal disorientation.[13]

- Atonic seizures involve the loss of muscle activity for greater than one second.[14] This typically occurs bilaterally (on both sides of the body).[14]

Duration

A seizure can last from a few seconds to more than five minutes, at which point it is known as status epilepticus.[17] Most tonic-clonic seizures last less than two or three minutes.[17] Absence seizures are usually around 10 seconds in duration.[12]

Postictal

After the active portion of a seizure, there is typically a period of confusion called the postictal period before a normal level of consciousness returns.[10] This usually lasts 3 to 15 minutes[18] but may last for hours.[19] Other common symptoms include: feeling tired, headache, difficulty speaking, and abnormal behavior.[19] Psychosis after a seizure is relatively common, occurring in between 6 and 10% of people.[20] Often people do not remember what occurred during this time.[19]

Causes

Seizures have a number of causes. Of those who have a seizure, about 25% have epilepsy.[21] A number of conditions are associated with seizures but are not epilepsy including: most febrile seizures and those that occur around an acute infection, stroke, or toxicity.[22] These seizures are known as "acute symptomatic" or "provoked" seizures and are part of the seizure-related disorders.[22] In many the cause is unknown.

Different causes of seizures are common in certain age groups.

- Seizures in babies are most commonly caused by hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, central nervous system (CNS) infections, trauma, congenital CNS abnormalities, and metabolic disorders.

- The most frequent cause of seizures in children is febrile seizures, which happen in 2–5% of children between the ages of six months and five years.[23]

- During childhood, well-defined epilepsy syndromes are generally seen.

- In adolescence and young adulthood, non-compliance with the medication regimen and sleep deprivation are potential triggers.

- Pregnancy and labor and childbirth, and the post-partum, or post-natal period (after birth) can be at-risk times, especially if there are certain complications like pre-eclampsia.

- During adulthood, the likely causes are alcohol related, strokes, trauma, CNS infections, and brain tumors.[24]

- In older adults, cerebrovascular disease is a very common cause. Other causes are CNS tumors, head trauma, and other degenerative diseases that are common in the older age group, such as dementia.[25]

Metabolic

Dehydration can trigger epileptic seizures if it is severe enough.[26] A number of disorders including: low blood sugar, low blood sodium, hyperosmolar nonketotic hyperglycemia, high blood sodium, low blood calcium and high blood urea levels may cause seizures.[16] As may hepatic encephalopathy and the genetic disorder porphyria.[16]

Mass lesions

- cavernoma or cavernous malformation is a treatable medical condition that can cause seizures, headaches, and brain hemorrhages.

- arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a treatable medical condition that can cause seizures, headaches, and brain hemorrhages.

- space-occupying lesions in the brain (abscesses, tumours). In people with brain tumours, the frequency of epilepsy depends on the location of the tumor in the cortical region.[27]

Medications

Both medication and drug overdoses can result in seizures,[16] as may certain medication and drug withdrawal.[16] Common drugs involved include: antidepressants, antipsychotics, cocaine, insulin, and the local anaesthetic lidocaine.[16] Difficulties with withdrawal seizures commonly occurs after prolonged alcohol or sedative use, a condition known as delirium tremens.[16]

Infections

- Infection with the pork tapeworm, which can cause neurocysticercosis, is the cause of up to half of epilepsy cases in areas of the world where the parasite is common.[28]

- parasitic infections such as cerebral malaria

- infection, such as encephalitis or meningitis[29]

Stress

Stress can induce seizures in people with epilepsy, and is a risk factor for developing epilepsy. Severity, duration, and time at which stress occurs during development all contribute to frequency and susceptibility to developing epilepsy. It is one of the most frequently self-reported triggers in patients with epilepsy.[30][31]

Stress exposure results in hormone release that mediates its effects in the brain. These hormones act on both excitatory and inhibitory neural synapses, resulting in hyper-excitability of neurons in the brain. The hippocampus is known to be a region that is highly sensitive to stress and prone to seizures. This is where mediators of stress interact with their target receptors to produce effects.[32]

Other

Seizures may occur as a result of high blood pressure, known as hypertensive encephalopathy, or in pregnancy as eclampsia when accompanied by either seizures or a decreased level of consciousness.[16] Very high body temperatures may also be a cause.[16] Typically this requires a temperature greater than 42 °C (107.6 °F).[16]

- Head injury may cause non-epileptic post-traumatic seizures or post-traumatic epilepsy

- About 3.5 to 5.5% of people with celiac disease also have seizures.[33]

- Seizures in a person with a shunt may indicate failure

- Hemorrhagic stroke can occasionally present with seizures, embolic strokes generally do not (though epilepsy is a common later complication); cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, a rare type of stroke, is more likely to be accompanied by seizures than other types of stroke

- Multiple sclerosis may cause seizures

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) deliberately sets out to induce a seizure for the treatment of major depression.

Mechanism

Normally brain electrical activity is non synchronous.[13] In epileptic seizures, due to problems within the brain,[9] a group of neurons begin firing in an abnormal, excessive,[11] and synchronized manner.[13] This results in a wave of depolarization known as a paroxysmal depolarizing shift.[34]

Normally after an excitatory neuron fires it becomes more resistant to firing for a period of time.[13] This is due in part from the effect of inhibitory neurons, electrical changes within the excitatory neuron, and the negative effects of adenosine.[13] In epilepsy the resistance of excitatory neurons to fire during this period is decreased.[13] This may occur due to changes in ion channels or inhibitory neurons not functioning properly.[13] This then results in a specific area from which seizures may develop, known as a "seizure focus".[13] Following an injury to the brain, another mechanism of epilepsy may be the up regulation of excitatory circuits or down regulation of inhibitory circuits.[13][35] These secondary epilepsies occur through processes known as epileptogenesis.[13][35] Failure of the blood–brain barrier may also be a causal mechanism.[36]

Focal seizures begin in one hemisphere of the brain while generalized seizures begin in both hemispheres.[15] Some types of seizures may change brain structure, while others appear to have little effect.[37] Gliosis, neuronal loss, and atrophy of specific areas of the brain are linked to epilepsy but it is unclear if epilepsy causes these changes or if these changes result in epilepsy.[37]

Seizure activity may be propagated through the brain's endogenous electrical fields.[38]

Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish primary seizures from secondary causes. Depending on the presumed cause blood tests and/or lumbar puncture may be useful.[6] Hypoglycemia may cause seizures and should be ruled out. An electroencephalogram and brain imaging with CT scan or MRI scan is recommended in the work-up of seizures not associated with a fever.[6][39]

Classification

Seizure types are organized by whether the source of the seizure is localized (focal seizures) or distributed (generalized seizures) within the brain.[15] Generalized seizures are divided according to the effect on the body and include tonic-clonic (grand mal), absence (petit mal), myoclonic, clonic, tonic, and atonic seizures.[15][40] Some seizures such as epileptic spasms are of an unknown type.[15]

Focal seizures (previously called partial seizures[11]) are divided into simple partial or complex partial seizure.[15] Current practice no longer recommends this, and instead prefers to describe what occurs during a seizure.[15]

Physical examination

Most people are in a postictal state (drowsy or confused) following a seizure. They may show signs of other injuries. A bite mark on the side of the tongue helps confirm a seizure when present, but only a third of people who have had a seizure have such a bite.[41]

Tests

An electroencephalography is only recommended in those who likely had an epileptic seizure and may help determine the type of seizure or syndrome present. In children it is typically only needed after a second seizure. It cannot be used to rule out the diagnosis and may be falsely positive in those without the disease. In certain situations it may be useful to prefer the EEG while sleeping or sleep deprived.[42]

Diagnostic imaging by CT scan and MRI is recommended after a first non-febrile seizure to detect structural problems inside the brain.[42] MRI is generally a better imaging test except when intracranial bleeding is suspected.[6] Imaging may be done at a later point in time in those who return to their normal selves while in the emergency room.[6] If a person has a previous diagnosis of epilepsy with previous imaging repeat imaging is not usually needed with subsequent seizures.[42]

In adults, testing electrolytes, blood glucose and calcium levels is important to rule these out as causes, as is an electrocardiogram.[42] A lumbar puncture may be useful to diagnose a central nervous system infection but is not routinely needed.[6] Routine antiseizure medical levels in the blood are not required in adults or children.[42] In children additional tests may be required.[42]

A high blood prolactin level within the first 20 minutes following a seizure may be useful to confirm an epileptic seizure as opposed to psychogenic non-epileptic seizure.[43][44] Serum prolactin level is less useful for detecting partial seizures.[45] If it is normal an epileptic seizure is still possible[44] and a serum prolactin does not separate epileptic seizures from syncope.[46] It is not recommended as a routine part of diagnosis epilepsy.[42]

Differential diagnosis

Differentiating an epileptic seizure from other conditions such as syncope can be difficult.[10] Other possible conditions that can mimic a seizure include: decerebrate posturing, psychogenic seizures, tetanus, dystonia, migraine headaches, and strychnine poisoning.[10] In addition, 5% of people with a positive tilt table test may have seizure-like activity that seems to be due to cerebral hypoxia.[47] Convulsions may occur due to psychological reasons and this is known as a psychogenic non-epileptic seizure. Non-epileptic seizures may also occur due to a number of other reasons.

Prevention

A number of measures have been attempted to prevent seizures in those at risk. Following traumatic brain injury anticonvulsants decrease the risk of early seizures but not late seizures.[48]

In those with a history of febrile seizures, medications (both antipyretics and anticonvulsants) have not been found effective for prevention. Some, in fact, may cause harm.[49]

There is no clear evidence that antiepileptic drugs are effective or not effective at preventing seizures following a craniotomy,[50] following subdural hematoma,[51] after a stroke,[52][53] or after subarachnoid haemorrhage,[54] for both people who have had a previous seizure, and those who have not.

Management

Potentially sharp or dangerous objects should be moved from the area around a person experiencing a seizure, so that the individual is not hurt. After the seizure if the person is not fully conscious and alert, they should be placed in the recovery position. A seizure longer than five minutes is a medical emergency known as status epilepticus.[17] Contrary to a common misconception, bystanders should not attempt to force objects into the mouth of the person suffering a seizure, as doing so may cause injury to the teeth and gums.[55]

Medication

The first line treatment of choice for someone who is actively seizing is a benzodiazepine, most guidelines recommend lorazepam. This may be repeated if there is no effect after 10 minutes. If there is no effect after two doses, barbiturates or propofol may be used.[39] Benzodiazepines given by a non-intravenous route appear to be better than those given by intravenous as the intravenous takes time to start.[56]

Ongoing anti-epileptic medications are not typically recommended after a first seizure except in those with structural lesions in the brain.[39] They are generally recommended after a second one has occurred.[39] Approximately 70% of people can obtain full control with continuous use of medication.[9] Typically one type of anticonvulsant is preferred. Following a first seizure, while immediate treatment with an anti-seizure drug lowers the probability of seizure recurrence up to five years it does not change the risk of death and there are potential side effects.[57]

In seizures related to toxins, up to two doses of benzodiazepines should be used. If this is not effective pyridoxine is recommended. Phenytoin should generally not be used.[58]

There is a lack of evidence for preventative anti-epileptic medications in the management of seizures related to intracranial venous thrombosis.[53]

Other

Helmets may be used to provide protection to the head during a seizure. Some claim that seizure response dogs, a form of service dog, can predict seizures. Evidence for this, however, is poor.[59] At present there is not enough evidence to support the use of cannabis for the management of seizures, although this is an ongoing area of research.[60][61] There is tentative evidence that a ketogenic diet may help in those who have epilepsy and is reasonable in those who do not improve following typical treatments.[62]

Prognosis

Following a first seizure, the risk of more seizures in the next two years is 40%–50%.[6] The greatest predictors of more seizures are problems either on the electroencephalogram or on imaging of the brain.[6] In adults, after 6 months of being seizure-free after a first seizure, the risk of a subsequent seizure in the next year is less than 20% regardless of treatment.[63] Up to 7% of seizures that present to the emergency department (ER) are in status epilepticus.[39] In those with a status epilepticus, mortality is between 10% and 40%.[10] Those who have a seizure that is provoked (occurring close in time to an acute brain event or toxic exposure) have a low risk of re-occurrence, but have a higher risk of death compared to those with epilepsy.[64]

Epidemiology

5–10% of people who live to 80 years old have at least one epileptic seizure[6][8] and the chance of experiencing a second seizure is between 40% and 50%.[7] About 0.7% in the general population of the United States go to an emergency department after a seizure in a given year,[10] 7% of them with status epilepticus.[24] Known epilepsy though is an uncommon cause of seizures in the emergency department, accounting for a minority of seizure-related visits.[24] About 50% of patients with an unprovoked apparent "first seizure" have had other minor seizures, so their diagnosis is epilepsy.[8]

History

The word epilepsy derives from the Greek word for "attack".[65] Seizures were long viewed as an otherworldly condition and this view was seen by Hippocrates (400 BC) as treating it as a sacred disease which he wrote about and concluded that it had natural causes just as other diseases did.[10][66]

In the mid 1800s the first anti seizure medication, bromide, was introduced.[67]

Following standardization proposals devised by Henri Gastaut and published in 1970,[68] terms such as "petit mal", "grand mal", "Jacksonian", "psychomotor", and "temporal-lobe seizure" have fallen into disuse.

Society and culture

Economics

Seizures result in direct economic costs of about one billion dollars in the United States.[6] Epilepsy results in economic costs in Europe of around 15.5 billion Euros in 2004.[11] In India, epilepsy is estimated to result in costs of 1.7 billion USD or 0.5% of the GDP.[9] They make up about 1% of emergency department visits (2% for emergency departments for children) in the United States.[24]

Driving

Many areas of the world require a minimum of six months from the last seizure before people can drive a vehicle.[6]

Research

Scientific work into the prediction of epileptic seizures began in the 1970s. Several techniques and methods have been proposed, but evidence regarding their usefulness is still lacking.[69]

References

- ↑ Shorvon, Simon (2009). Epilepsy. OUP Oxford. p. 1. ISBN 9780199560042.

- ↑ Misulis, Karl E.; Murray, E. Lee (2017). Essentials of Hospital Neurology. Oxford University Press. p. Chapter 19. ISBN 9780190259433. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017.

- 1 2 Fisher R, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J (2005). "Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE)". Epilepsia. 46 (4): 470–2. PMID 15816939.

- ↑ Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, Engel J, Forsgren L, French JA, Glynn M, Hesdorffer DC, Lee BI, Mathern GW, Moshé SL, Perucca E, Scheffer IE, Tomson T, Watanabe M, Wiebe S (Apr 2014). "ILAE Official Report: A practical clinical definition of epilepsy". Epilepsia. 55 (4): 475–82. doi:10.1111/epi.12550. PMID 24730690.

- ↑ "What Is A Seizure Emergency". epilepsy.com. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Wilden, JA; Cohen-Gadol, AA (Aug 15, 2012). "Evaluation of first nonfebrile seizures". American Family Physician. 86 (4): 334–40. PMID 22963022.

- 1 2 Berg, AT (2008). "Risk of recurrence after a first unprovoked seizure". Epilepsia. 49 Suppl 1: 13–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01444.x. PMID 18184149.

- 1 2 3 Angus-Leppan H (2014). "First seizures in adults". BMJ. 348: g2470. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2470. PMID 24736280.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Epilepsy". Fact Sheets. World Health Organization. October 2012. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Shearer, Peter. "Seizures and Status Epilepticus: Diagnosis and Management in the Emergency Department". Emergency Medicine Practice. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (January 2012). "Chapter 1: Introduction". The Epilepsies: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care (PDF). National Clinical Guideline Centre. pp. 21–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2013.

- 1 2 Hughes, JR (August 2009). "Absence seizures: a review of recent reports with new concepts". Epilepsy & Behavior. 15 (4): 404–12. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.06.007. PMID 19632158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Hammer, edited by Stephen J. McPhee, Gary D. (2010). "7". Pathophysiology of disease : an introduction to clinical medicine (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-162167-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bradley, Walter G. (2012). "67". Bradley's neurology in clinical practice (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (January 2012). "Chapter 9: Classification of seizures and epilepsy syndromes". The Epilepsies: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care (PDF). National Clinical Guideline Centre. pp. 119–129. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Simon, David A. Greenberg, Michael J. Aminoff, Roger P. (2012). "12". Clinical neurology (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-175905-2.

- 1 2 3 Trinka, E; Höfler, J; Zerbs, A (September 2012). "Causes of status epilepticus". Epilepsia. 53 Suppl 4: 127–38. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03622.x. PMID 22946730.

- ↑ Holmes, Thomas R. (2008). Handbook of epilepsy (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7817-7397-3. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 Panayiotopoulos, CP (2010). A clinical guide to epileptic syndromes and their treatment based on the ILAE classifications and practice parameter guidelines (Rev. 2nd ed.). [London]: Springer. p. 445. ISBN 978-1-84628-644-5. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016.

- ↑ James W. Wheless, ed. (2009). Advanced therapy in epilepsy. Shelton, Conn.: People's Medical Pub. House. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-60795-004-2. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Stasiukyniene, V.; Pilvinis, V.; Reingardiene, D.; Janauskaite, L. (2009). "[Epileptic seizures in critically ill patients]". Medicina (Kaunas). 45 (6): 501–7. PMID 19605972.

- 1 2 Thurman DJ, Beghi E, Begley CE, Berg AT, Buchhalter JR, Ding D, Hesdorffer DC, Hauser WA, Kazis L, Kobau R, Kroner B, Labiner D, Liow K, Logroscino G, Medina MT, Newton CR, Parko K, Paschal A, Preux PM, Sander JW, Selassie A, Theodore W, Tomson T, Wiebe S (September 2011). "Standards for epidemiologic studies and surveillance of epilepsy". Epilepsia. 52 Suppl 7: 2–26. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03121.x. PMID 21899536.

- ↑ Graves, RC; Oehler, K; Tingle, LE (Jan 15, 2012). "Febrile seizures: risks, evaluation, and prognosis". American Family Physician. 85 (2): 149–53. PMID 22335215.

- 1 2 3 4 Martindale JL, Goldstein JN, Pallin DJ (2011). "Emergency department seizure epidemiology". Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 29 (1): 15–27. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2010.08.002. PMID 21109099.

- ↑ Harrison's Principles of Medicine. 15th edition

- ↑ "diet and nutrition". Archived from the original on 29 June 2015.

- ↑ Hildebrand, J (July 2004). "Management of epileptic seizures". Curr Opin Oncol. 16 (4): 314–7. doi:10.1097/01.cco.0000127720.17558.38. PMID 15187884.

- ↑ Bhalla, D.; Godet, B.; Druet-Cabanac, M.; Preux, PM. (Jun 2011). "Etiologies of epilepsy: a comprehensive review". Expert Rev Neurother. 11 (6): 861–76. doi:10.1586/ern.11.51. PMID 21651333.

- ↑ Carlson, Neil (January 22, 2012). Physiology of Behavior. Neurological Disorders. 11th edition. Pearson. p. 550. ISBN 0-205-23939-0.

- ↑ Nakken, Karl O.; Solaas, Marit H.; Kjeldsen, Marianne J.; Friis, Mogens L.; Pellock, John M.; Corey, Linda A. (2005). "Which seizure-precipitating factors do patients with epilepsy most frequently report?". Epilepsy & Behavior. 6 (1): 85–89. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.11.003.

- ↑ Haut, Sheryl R.; Hall, Charles B.; Masur, Jonathan; Lipton, Richard B. (2007-11-13). "Seizure occurrence: precipitants and prediction". Neurology. 69 (20): 1905–1910. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000278112.48285.84. ISSN 1526-632X. PMID 17998482.

- ↑ Gunn, B.G.; Baram, T.Z. (2017). "Stress and Seizures: Space, Time and Hippocampal Circuits". Trends in Neurosciences. 40 (11): 667–679. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.08.004.

- ↑ Bushara, KO (April 2005). "Neurologic presentation of celiac disease". Gastroenterology. 128 (4 Suppl 1): S92–7. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.018. PMID 15825133.

- ↑ Somjen, George G. (2004). Ions in the Brain Normal Function, Seizures, and Stroke. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-803459-9. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- 1 2 Goldberg, EM; Coulter, DA (May 2013). "Mechanisms of epileptogenesis: a convergence on neural circuit dysfunction". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 14 (5): 337–49. doi:10.1038/nrn3482. PMC 3982383. PMID 23595016.

- ↑ Oby, E; Janigro, D (Nov 2006). "The blood-brain barrier and epilepsy". Epilepsia. 47 (11): 1761–74. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00817.x. PMID 17116015.

- 1 2 Jerome Engel, Jr.; Timothy A. Pedley, eds. (2008). Epilepsy : a comprehensive textbook (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 483. ISBN 978-0-7817-5777-5.

- ↑ Qiu, Chen; Shivacharan, Rajat S; Zhang, Mingming; Durand, Dominique M (2015). "Can Neural Activity Propagate by Endogenous Electrical Field?". The Journal of Neuroscience. 35 (48): 15800–11. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1045-15.2015. PMC 4666910. PMID 26631463. Lay summary.

electric fields can be solely responsible for spike propagation at ... This phenomenon could be important to explain the slow propagation of epileptic activity and other normal propagations at similar speeds.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Current Guidelines For Management Of Seizures In The Emergency Department" (PDF). Archived from the original on 30 December 2010.

- ↑ Simon D. Shorvon (2004). The treatment of epilepsy (2nd ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-0-632-06046-7. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Peeters, SY; Hoek, AE; Mollink, SM; Huff, JS (April 2014). "Syncope: risk stratification and clinical decision making". Emergency medicine practice. 16 (4): 1–22, quiz 22–3. PMID 25105200.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (January 2012). "4". The Epilepsies: The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care (PDF). National Clinical Guideline Centre. pp. 57–83.

- ↑ Luef, G (October 2010). "Hormonal alterations following seizures". Epilepsy & Behavior. 19 (2): 131–3. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.06.026. PMID 20696621.

- 1 2 Ahmad S, Beckett MW (2004). "Value of serum prolactin in the management of syncope". Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 21 (2): e3. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.008870. PMC 1726305. PMID 14988379.

- ↑ Shukla G, Bhatia M, Vivekanandhan S, et al. (2004). "Serum prolactin levels for differentiation of nonepileptic versus true seizures: limited utility". Epilepsy & Behavior. 5 (4): 517–21. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.03.004. PMID 15256189.

- ↑ Chen DK, So YT, Fisher RS (2005). "Use of serum prolactin in diagnosing epileptic seizures: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 65 (5): 668–75. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000178391.96957.d0. PMID 16157897.

- ↑ Passman R, Horvath G, Thomas J, et al. (2003). "Clinical spectrum and prevalence of neurologic events provoked by tilt table testing". Arch. Intern. Med. 163 (16): 1945–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.16.1945. PMID 12963568.

- ↑ Weston, J; Greenhalgh, J; Marson, AG (4 March 2015). "Antiepileptic drugs as prophylaxis for post-craniotomy seizures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD007286. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007286.pub3. PMID 25738821.

- ↑ Offringa, Martin; Newton, Richard; Cozijnsen, Martinus A.; Nevitt, Sarah J. (2017). "Prophylactic drug management for febrile seizures in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD003031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003031.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 28225210.

- ↑ Weston, Jennifer; Greenhalgh, Janette; Marson, Anthony G. (2015-03-04). "Antiepileptic drugs as prophylaxis for post-craniotomy seizures". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD007286. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007286.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25738821.

- ↑ Ratilal, BO; Pappamikail, L; Costa, J; Sampaio, C (Jun 6, 2013). "Anticonvulsants for preventing seizures in patients with chronic subdural haematoma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD004893. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004893.pub3. PMID 23744552.

- ↑ Sykes, L; Wood, E; Kwan, J (24 January 2014). "Antiepileptic drugs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures after stroke". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005398. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005398.pub3. PMID 24464793.

- 1 2 Price, Michelle; Günther, Albrecht; Kwan, Joseph S. K. (2016-04-21). "Antiepileptic drugs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures after intracranial venous thrombosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD005501. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005501.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 27098266.

- ↑ Marigold, R; Günther, A; Tiwari, D; Kwan, J (Jun 5, 2013). "Antiepileptic drugs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures after subarachnoid haemorrhage". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD008710. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008710.pub2. PMID 23740537.

- ↑ O’connor, Anahad (22 April 2008). "The Claim: During a Seizure, You Can Swallow Your Tongue". Archived from the original on 6 March 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- ↑ Alshehri, A; Abulaban, A; Bokhari, R; Kojan, S; Alsalamah, M; Ferwana, M; Murad, MH (25 March 2017). "Intravenous versus Non-Intravenous Benzodiazepines for the Abortion of Seizures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Academic Emergency Medicine. 24: 875–883. doi:10.1111/acem.13190. PMID 28342192.

- ↑ Leone, MA; Giussani, G; Nolan, SJ; Marson, AG; Beghi, E (6 May 2016). "Immediate antiepileptic drug treatment, versus placebo, deferred, or no treatment for first unprovoked seizure". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD007144. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007144.pub2. PMID 27150433. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ Sharma, AN; Hoffman, RJ (Feb 2011). "Toxin-related seizures". Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 29 (1): 125–39. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2010.08.011. PMID 21109109.

- ↑ Doherty, MJ; Haltiner, AM (Jan 23, 2007). "Wag the dog: skepticism on seizure alert canines". Neurology. 68 (4): 309. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000252369.82956.a3. PMID 17242343.

- ↑ Gloss, D; Vickrey, B (5 March 2014). "Cannabinoids for epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD009270. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009270.pub3. PMID 24595491.

- ↑ Belendiuk, KA; Baldini, LL; Bonn-Miller, MO (21 April 2015). "Narrative review of the safety and efficacy of marijuana for the treatment of commonly state-approved medical and psychiatric disorders". Addiction science & clinical practice. 10 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s13722-015-0032-7. PMC 4636852. PMID 25896576.

- ↑ Martin, K; Jackson, CF; Levy, RG; Cooper, PN (9 February 2016). "Ketogenic diet and other dietary treatments for epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD001903. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001903.pub3. PMID 26859528.

- ↑ Bonnett, LJ; Tudur-Smith, C; Williamson, PR; Marson, AG (2010-12-07). "Risk of recurrence after a first seizure and implications for driving: further analysis of the Multicentre study of early Epilepsy and Single Seizures". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 341: c6477. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6477. PMC 2998675. PMID 21147743.

- ↑ Neligan, A; Hauser, WA; Sander, JW (2012). "The epidemiology of the epilepsies". Handbook of clinical neurology. 107: 113–33. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52898-8.00006-9. PMID 22938966. ; Sander JW, Shorvon SD (1996). "Epidemiology of the epilepsies". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 61: 433–43. doi:10.1136/jnnp.61.5.433. PMC 1074036. PMID 8965090.

- ↑ "Epilepsy (Seizure Disorder)". Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ↑ "On the Sacred Disease". Archived from the original on 24 May 2011.

- ↑ Perucca, P; Gilliam, FG (September 2012). "Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs". Lancet Neurology. 11 (9): 792–802. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70153-9. PMID 22832500.

- ↑ Gastaut H (1970). "Clinical and electroencephalographical classification of epileptic seizures". Epilepsia. 11 (1): 102–13. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1970.tb03871.x. PMID 5268244.

- ↑ Litt B, Echauz J (May 2002). "Prediction of epileptic seizures". Lancet Neurol. 1 (1): 22–30. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(02)00003-0. PMID 12849542.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up epileptic seizure in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Epileptic seizure at Curlie (based on DMOZ)