Dantrolene

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names |

Dantrium (in North America) Dantrolen (in Europe) Dantamacrin (in Europe , Russia) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 70% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Excretion | Biliary, renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.027.895 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

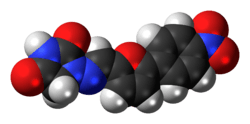

| Formula | C14H10N4O5 |

| Molar mass | 314.253 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Dantrolene sodium is a postsynaptic muscle relaxant that lessens excitation-contraction coupling in muscle cells. It achieves this by inhibiting Ca2+ ions release from sarcoplasmic reticulum stores by antagonizing ryanodine receptors.[1] It is the primary drug used for the treatment and prevention of malignant hyperthermia, a rare, life-threatening disorder triggered by general anesthesia. It is also used in the management of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, muscle spasticity (e.g. after strokes, in paraplegia, cerebral palsy, or patients with multiple sclerosis), and 2,4-dinitrophenol poisoning,[2][3] and the related compounds dinoseb and dinoterb.[4]

It is marketed by Par Pharmaceuticals LLC as Dantrium (in North America) and by Norgine BV as Dantrium, Dantamacrin, or Dantrolen (in Europe). A hospital is recommended to keep a minimum stock of 36 dantrolene vials totaling 720 mg, sufficient for a 70-kg person.[5] As of 2015 the cost for a typical course of medication in the United States is 100 to 200 USD.[6]

History

Dantrolene was first described in the scientific literature in 1967, as one of several hydantoin derivatives proposed as a new class of muscle relaxant.[7] Dantrolene underwent extensive further development, and its action on skeletal muscle was described in detail in 1973.[8]

Dantrolene was widely used in the management of spasticity[9] before its efficacy in treating malignant hyperthermia was discovered by South African anesthesiologist Gaisford Harrison and reported in a landmark 1975 article published in the British Journal of Anaesthesia.[10] Harrison experimentally induced malignant hyperthermia with halothane anesthesia in genetically susceptible pigs, and obtained an 87.5% survival rate, where seven of his eight experiments survived after intravenous administration of dantrolene. The efficacy of dantrolene in humans was later confirmed in a large, multicenter study published in 1982,[11] and confirmed epidemiologically in 1993.[12] Before dantrolene, the only available treatment for malignant hyperthermia was procaine, which was associated with a 60% mortality rate in animal models.[10]

Contraindications

Oral dantrolene cannot be used by:

- people with a pre-existing liver disease

- people with compromised lung function

- people with severe cardiovascular impairment

- people with a known hypersensitivity to dantrolene

- pediatric patients under five years of age

- people who need good muscular balance or strength to maintain an upright position, motoric function, or proper neuromuscular balance

If the indication is a medical emergency, such as malignant hyperthermia, the only significant contraindication is hypersensitivity.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

If needed in pregnancy, adequate human studies are lacking, therefore the drug should be given in pregnant women only if clearly indicated. It may cause hypotonia in the newborn if given closely before delivery.[4]

Dantrolene should not be given to breastfeeding mothers. If a treatment is necessary, breastfeeding should be terminated.

Adverse effects

Central nervous system side effects are quite frequently noted and encompass speech and visual disturbances, mental depression and confusion, hallucinations, headache, insomnia and exacerbation or precipitation of seizures, and increased nervousness. Infrequent cases of respiratory depression or a feeling of suffocation have been observed. Dantrolene often causes sedation severe enough to incapacitate the patient to drive or operate machinery.

Gastrointestinal effects include bad taste, decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea.

Liver side effects may be seen either as asymptomatic elevation of liver enzymes and/or bilirubin or, most severe, as fatal and nonfatal liver inflammation. The risk of liver inflammation is associated with the duration of treatment and the daily dose. In patients treated for hyperthermia, no liver toxicity has been observed so far. Patients on chronic dantrolene therapy should routinely have LFTs monitored.

Pleural effusion with inflammation of the fibrous sac around the heart (oral treatment only), rare cases of bone marrow damage, diffuse muscle pains, backache, dermatologic reactions, transient cardiovascular reactions, and crystals in the urine have additionally been seen. Muscle weakness may persist for several days following treatment.

Mutagenicity and carcinogenity

It is currently unclear whether Dantrolene has carcinogenic effects.

Mechanism of action

Dantrolene depresses excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle by acting as a receptor antagonist to the ryanodine receptor, and decreasing free intracellular calcium concentration.[4]

Chemistry

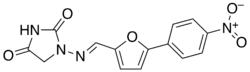

Chemically it is a hydantoin derivative, but does not exhibit antiepileptic activity like other hydantoin derivates such as phenytoin.[4]

The poor water solubility of dantrolene leads to certain difficulties in its use.[4][13] A more water-soluble analog of dantrolene, azumolene, is under development for similar indications.[13] Azumolene has a bromine residue instead of the nitro group found in dantrolene, and is 30 times more water-soluble.[4]

Drug interactions

Dantrolene may interact with the following drugs:[14]

- Calcium channel blockers of the diltiazem/verapamil type: Intravenous treatment with dantrolene and concomitant calcium channel blocker treatment may lead to severe cardiovascular collapse, abnormal heart rhythms, myocardial depressions, and high blood potassium.

- Nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents, such as vecuronium bromide: Neuromuscular blockade is potentiated.

- CNS depressants: Sedative action is potentiated. Benzodiazepines may also cause additive muscle weakness.

- Combined oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy with estrogens may enhance liver toxicity of dantrolene, particularly in women over 35 years of age.

Synthesis

The original patent synthesis started with para-nitroaniline which undergoes diazotization followed by a copper(II) chloride catalyzed arylation with furfural (essentially a modified Meerwein arylation). This then reacts with 1-aminohydantoin to form the final product.

References

- ↑ Zucchi, R; Ronca-Testoni, S (March 1997). "The sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channel/ryanodine receptor: modulation by endogenous effectors, drugs and disease states". Pharmacological Reviews. 49 (1): 1–51. PMID 9085308.

- ↑ Kumar S, Barker K, Seger D (2002). "Dinitrophenol-Induced Hyperthermia Resolving With Dantrolene Administration. Abstracts of the North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology". Clin Toxicol. 40 (5): 599–673. doi:10.1081/clt-120016859.

- ↑ Barker K, Seger D, Kumar S (2006). "Comment on "Pediatric fatality following ingestion of Dinitrophenol: postmortem identification of a 'dietary supplement'"". Clin Toxicol. 44 (3): 351. doi:10.1080/15563650600584709. PMID 16749560.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Krause T, Gerbershagen MU, Fiege M, Weisshorn R, Wappler F (2004). "Dantrolene – a review of its pharmacology, therapeutic use and new developments". Anaesthesia. 59 (4): 364–73. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03658.x. PMID 15023108.

- ↑ Yeung EY, Munroe J (2015). "Development of a malignant hyperthermia protocol" (PDF). BMC Proceedings. 9 (Suppl1): A32. doi:10.1186/1753-6561-9-S1-A32. PMC 4306034.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 2. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ Snyder HR, Davis CS, Bickerton RK, Halliday RP (September 1967). "1-[(5-arylfurfurylidene)amino]hydantoins. A new class of muscle relaxants". J Med Chem. 10 (5): 807–10. doi:10.1021/jm00317a011. PMID 6048486.

- ↑ Ellis KO, Castellion AW, Honkomp LJ, Wessels FL, Carpenter JE, Halliday RP (June 1973). "Dantrolene, a direct acting skeletal muscle relaxant". J Pharm Sci. 62 (6): 948–51. doi:10.1002/jps.2600620619. PMID 4712630.

- ↑ Pinder, RM; Brogden, RN; Speight, TM; Avery, GS (January 1977). "Dantrolene sodium: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy in spasticity". Drugs. 13 (1): 3–23. doi:10.2165/00003495-197713010-00002. PMID 318989.

- 1 2 Harrison GG (January 1975). "Control of the malignant hyperpyrexic syndrome in MHS swine by dantrolene sodium". Br J Anaesth. 47 (1): 62–5. doi:10.1093/bja/47.1.62. PMID 1148076. A reprint of the article, which became a "Citation Classic", is available in Br J Anaesth 81 (4): 626–9. PMID 9924249 (free full text).

- ↑ Kolb ME, Horne ML, Martz R (April 1982). "Dantrolene in human malignant hyperthermia". Anesthesiology. 56 (4): 254–62. doi:10.1097/00000542-198204000-00005. PMID 7039419.

- ↑ Strazis KP, Fox AW (March 1993). "Malignant hyperthermia: review of published cases". Anesth Analg. 77 (3): 297–304. doi:10.1213/00000539-199377020-00014.

- 1 2 Sudo RT, Carmo PL, Trachez MM, Zapata-Sudo G (March 2008). "Effects of azumolene on normal and malignant hyperthermia-susceptible skeletal muscle". Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 102 (3): 308–16. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00156.x. PMID 18047479.

- ↑ "Dantrolene Drug Interactions". Epocrates Online. Epocrates. 2008. Retrieved on December 31, 2008.

- ↑ Snyder, H. R.; Davis, C. S.; Bickerton, R. K.; Halliday, R. P. (1967). "1-[5-Arylfurfurylidene)amino]hydantoins. A New Class of Muscle Relaxants". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 10 (5): 807–10. doi:10.1021/jm00317a011. PMID 6048486.

External links

- http://www.kompendium.ch/MonographieTxt.aspx?lang=de&MonType=fi%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D Swiss Drug Compendium on oral Dantrolene (German)