Amazon (company)

| |

| Amazon | |

Formerly | Cadabra, Inc. (1994–95) |

| Public | |

| Traded as |

|

| ISIN | US0231351067 |

| Industry | Online shopping |

| Founded | July 5, 1994 |

| Founder | Jeff Bezos |

| Headquarters | Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | |

| Revenue |

|

|

| |

|

| |

| Total assets |

|

| Total equity |

|

Number of employees |

|

| Subsidiaries |

|

| Website |

www |

Amazon.com, Inc., doing business as Amazon (/ˈæməˌzɒn/), is an American electronic commerce and cloud computing company based in Seattle, Washington, that was founded by Jeff Bezos on July 5, 1994. The tech giant is the largest Internet retailer in the world as measured by revenue and market capitalization, and second largest after Alibaba Group in terms of total sales.[3] The amazon.com website started as an online bookstore and later diversified to sell video downloads/streaming, MP3 downloads/streaming, audiobook downloads/streaming, software, video games, electronics, apparel, furniture, food, toys, and jewelry. The company also produces consumer electronics—Kindle e-readers, Fire tablets, Fire TV, and Echo—and is the world's largest provider of cloud infrastructure services (IaaS and PaaS).[4] Amazon also sells certain low-end products under its in-house brand AmazonBasics.

Amazon has separate retail websites for the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland, France, Canada, Germany, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, Australia, Brazil, Japan, China, India, Mexico, Singapore, and Turkey. In 2016, Dutch, Polish, and Turkish language versions of the German Amazon website were also launched.[5][6][7] Amazon also offers international shipping of some of its products to certain other countries.[8]

In 2015, Amazon surpassed Walmart as the most valuable retailer in the United States by market capitalization.[9] Amazon is the second most valuable public company in the world (behind only Apple), the largest Internet company by revenue in the world, and after Walmart, the second largest employer in the United States.[10] In 2017, Amazon acquired Whole Foods Market for $13.4 billion, which vastly increased Amazon's presence as a brick-and-mortar retailer.[11] The acquisition was interpreted by some as a direct attempt to challenge Walmart's traditional retail stores.[12] In 2018, for the first time, Jeff Bezos released in Amazon's shareholder letter the number of Amazon Prime subscribers, which is 100 million worldwide.[13][14] On September 4, 2018, Amazon reached US$1 trillion in value, becoming the second publicly traded US company to do so after Apple.[15][16]

History

The company was founded as a result of what Jeff Bezos called his "regret minimization framework," which described his efforts to fend off any regrets for not participating sooner in the Internet business boom during that time.[17] In 1994, Bezos left his employment as vice-president of D. E. Shaw & Co., a Wall Street firm, and moved to Seattle, Washington, where he began to work on a business plan[18] for what would become Amazon.com.

On July 5, 1994, Bezos initially incorporated the company in Washington State with the name Cadabra, Inc.[19] He later changed the name to Amazon.com, Inc. a few months later, after a lawyer misheard its original name as "cadaver".[20] In September 1994, Bezos purchased the URL Relentless.com and briefly considered naming his online store Relentless, but friends told him the name sounded a bit sinister. The domain is still owned by Bezos and still redirects to the retailer.[21][22]

Choosing a name

Bezos selected the name Amazon by looking through the dictionary; he settled on "Amazon" because it was a place that was "exotic and different", just as he had envisioned for his Internet enterprise. The Amazon River, he noted, was the biggest river in the world, and he planned to make his store the biggest bookstore in the world.[23] Additionally, a name that began with "A" was preferential due to the probability it would occur at the top of an alphabetized list.[23] Bezos placed a premium on his head start in building a brand and told a reporter, "There's nothing about our model that can't be copied over time. But you know, McDonald's got copied. And it's still built a huge, multibillion-dollar company. A lot of it comes down to the brand name. Brand names are more important online than they are in the physical world."[24]

Online bookstore and IPO

After reading a report about the future of the Internet that projected annual web commerce growth at 2,300%, Bezos created a list of 20 products that could be marketed online. He narrowed the list to what he felt were the five most promising products, which included: compact discs, computer hardware, computer software, videos, and books. Bezos finally decided that his new business would sell books online, due to the large worldwide demand for literature, the low price points for books, along with the huge number of titles available in print.[25] Amazon was founded in the garage of Bezos' rented home in Bellevue, Washington.[23][26][27] Bezos' parents invested almost $250,000 in the start-up.[28]

In July 1995, the company began service as an online bookstore.[29] The first book sold on Amazon.com was Douglas Hofstadter's Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought.[30] In the first two months of business, Amazon sold to all 50 states and over 45 countries. Within two months, Amazon's sales were up to $20,000/week.[31] In October 1995, the company announced itself to the public.[32] In 1996, it was reincorporated in Delaware. Amazon issued its initial public offering of stock on May 15, 1997, at $18 per share, trading under the NASDAQ stock exchange symbol AMZN.[33]

Barnes & Noble sued Amazon on May 12, 1997, alleging that Amazon's claim to be "the world's largest bookstore" was false because it "...isn't a bookstore at all. It's a book broker." The suit was later settled out of court and Amazon continued to make the same claim.[34] Walmart sued Amazon on October 16, 1998, alleging that Amazon had stolen Walmart's trade secrets by hiring former Walmart executives. Although this suit was also settled out of court, it caused Amazon to implement internal restrictions and the reassignment of the former Walmart executives.[34]

In 1999, Amazon first attempted to enter the publishing business by buying a defunct imprint, "Weathervane", and publishing some books "selected with no apparent thought", according to The New Yorker. The imprint quickly vanished again, and as of 2014 Amazon representatives said that they had never heard of it.[35] Also in 1999, Time magazine named Bezos the Person of the Year when it recognized the company's success in popularizing online shopping.[36]

2000's

Since June 19, 2000, Amazon's logotype has featured a curved arrow leading from A to Z, representing that the company carries every product from A to Z, with the arrow shaped like a smile.[37]

According to sources, Amazon did not expect to make a profit for four to five years. This comparatively slow growth caused stockholders to complain that the company was not reaching profitability fast enough to justify their investment or even survive in the long-term. The dot-com bubble burst at the start of the 21st century and destroyed many e-companies in the process, but Amazon survived and moved forward beyond the tech crash to become a huge player in online sales. The company finally turned its first profit in the fourth quarter of 2001: $5 million (i.e., 1¢ per share), on revenues of more than $1 billion. This profit margin, though extremely modest, proved to skeptics that Bezos' unconventional business model could succeed.[38]

2010 to present

In 2011, Amazon had 30,000 full-time employees in the USA, and by the end of 2016, it had 180,000 employees.

| Wikinews has related news: Amazon.com to acquire Whole Foods at US$42 per share |

In June 2017, Amazon announced that it would acquire Whole Foods, a high-end supermarket chain with over 400 stores, for $13.4 billion.[11][39] The acquisition was seen by media experts as a move to strengthen its physical holdings and challenge Walmart's supremacy as a brick and mortar retailer. This sentiment was heightened by the fact that the announcement coincided with Walmart's purchase of men's apparel company Bonobos.[40] On August 23, 2017, Whole Foods shareholders, as well as the Federal Trade Commission, approved the deal.[41][42]

In September 2017, Amazon announced plans to locate a second headquarters in a metropolitan area with at least a million people.[43] Cities needed to submit their presentations by October 19, 2017 for the project called HQ2.[44] The $5 billion second headquarters, starting with 500,000 square feet and eventually expanding to as much as 8 million square feet, may have as many as 50,000 employees.[45] In 2017, Amazon announced it would build a new downtown Seattle building with space for Mary's Place, a local charity in 2020.[46]

At the end of 2017, Amazon had over 566,000 employees worldwide.[47][48]

According to an August 8, 2018 story in Bloomberg Businessweek, Amazon has about a 5 percent share of U.S. retail spending (excluding cars and car parts and visits to restaurants and bars), and a 43.5 share of American online spending in 2018. The forecast is for Amazon to own 49 percent of the total American online spending in 2018, with two-thirds of Amazon's revenue coming from the U.S.[49]

Amazon launched the last-mile delivery program and ordered 20,000 Mercedes-Benz Sprinter Vans for the service in September 2018.[50][51]

Amazon Go

On January 22, 2018, Amazon Go, a store that uses cameras and sensors to detect items that a shopper grabs off shelves and automatically charges a shopper's Amazon account, was opened to the general public in Seattle.[52][53] Customers scan their Amazon Go app as they enter, and are required to have an Amazon Go app installed on their smartphone and a linked Amazon account to be able to enter.[52] The technology is meant to eliminate the need for checkout lines.[54][55][56] Amazon Go was initially opened for Amazon employees in December 2016.[57][58][59] In August 2018, the second Amazon Go store opened its doors.[60][61]

Amazon 4-Star

Amazon announced to debut the Amazon 4-star in New York, Soho neighborhood Spring Street between Crosby and Lafayette on 27 September 2018. The store carries the 4-star and above rated products from around New York.[62] The amazon website searches for the most rated, highly demanded, frequently bought and most wished for products which are then sold in the new amazon store under separate categories. Along with the paper price tags, the online-review cards will also be available for the customers to read before buying the product.[63][64]

Mergers and acquisitions

Amazon has grown through a number of mergers and acquisitions over the years.

The company has also invested in a number of growing firms, both in the United States and Internationally.[65][66] In 2014, Amazon purchased top level domain .buy in auction for over $4 million.[67][68] The company has invested in brands that offer a wide range of services and products, including Engine Yard, a Ruby-on-Rails platform as a service company,[69] and Living Social, a local deal site.[70]

Board of directors

As of May 2018, the board of directors is:[71]

- Jeff Bezos, President, CEO, and Chairman

- Tom Alberg, Managing partner, Madrona Venture Group

- John Seely Brown, Visiting Scholar and Advisor to the Provost at University of Southern California

- Jamie Gorelick, partner, Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale, and Dorr

- Daniel P. Huttenlocher, Dean and Vice Provost, Cornell University

- Judy McGrath, former CEO, MTV Networks

- Jon Rubinstein, former Chairman, and CEO, Palm, Inc.

- Thomas O. Ryder, former Chairman, and CEO, Reader's Digest Association

- Patty Stonesifer, President, and CEO, Martha's Table

- Wendell P. Weeks, Chairman, President, and CEO, Corning Inc.

Merchant partnerships

Until June 30, 2006, typing ToysRUs.com into a browser would bring up Amazon.com's "Toys & Games" tab; however, this relationship was terminated due to a lawsuit.[72] Amazon also hosted and managed the website for Borders bookstores but this ceased in 2008.[73] From 2001 until August 2011, Amazon hosted the retail website for Target.[74]

Amazon.com operates retail websites for Sears Canada, Bebe Stores, Marks & Spencer, Mothercare, and Lacoste. For a growing number of enterprise clients, including the UK merchants Marks & Spencer, Benefit Cosmetics' UK entity, edeals.com and Mothercare, Amazon provides a unified multichannel platform where a customer can interact with the retail website, standalone in-store terminals or phone-based customer service agents. Amazon Web Services also powers AOL's Shop@AOL.

On October 18, 2011, Amazon.com announced a partnership with DC Comics for the exclusive digital rights to many popular comics, including Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, The Sandman, and Watchmen. The partnership has caused well-known bookstores like Barnes & Noble to remove these titles from their shelves.[75]

In November 2013, Amazon.com announced a partnership with the United States Postal Service to begin delivering orders on Sundays. The service, included in Amazon's standard shipping rates, initiated in metropolitan areas of Los Angeles and New York due to the high-volume and inability to deliver timely, with plans to expand into Dallas, Houston, New Orleans and Phoenix by 2014.[76]

In July 2016, Amazon.com announced a partnership with the UK Civil Aviation Authority to test some of the technologies and may use delivery service via prime air drone in the future.[77]

In June 2017, Nike confirmed a partnership with Amazon, stating it to be in an initial phase where they'll be selling goods on Amazon.[78][79][80]

As of October 11, 2017, AmazonFresh sells a range of Booths branded products for home delivery in selected areas.[81]

In September 2017, Amazon ventured with one of its sellers JV Appario Retail owned by Patni Group which has recorded a total income of $104.44 Mn (INR 759 Cr) in financial year 2017-18.[82]

Products and services

Amazon.com's product lines available at its website include several media (books, DVDs, music CDs, videotapes and software), apparel, baby products, consumer electronics, beauty products, gourmet food, groceries, health and personal-care items, industrial & scientific supplies, kitchen items, jewelry, watches, lawn and garden items, musical instruments, sporting goods, tools, automotive items and toys & games.

Amazon is now gearing up in India to play a role in the grocery retail sector aimed at delivering customer needs.[83]

Amazon.com has a number of products and services available, including:

Subsidiaries

Amazon owns over 40 subsidiaries, including Zappos, Shopbop, Diapers.com, Kiva Systems (now Amazon Robotics), Audible, Goodreads, Teachstreet and IMDb.[84]

A9.com

A9.com, a company focused on researching and building innovative technology, has been a subsidiary since 2003. [85]

Amazon Maritime

Amazon Maritime, Inc. holds a Federal Maritime Commission license to operate as a non-vessel-owning common carrier (NVOCC), which enables the company to manage its own shipments from China into the United States.[86]

Audible.com

Audible.com is a seller and producer of spoken audio entertainment, information and educational programming on the Internet. Audible sells digital audiobooks, radio and TV programs and audio versions of magazines and newspapers. Through its production arm, Audible Studios, Audible has also become the world's largest producer of downloadable audiobooks. On January 31, 2008, Amazon announced it would buy Audible for about $300 million. The deal closed in March 2008 and Audible became a subsidiary of Amazon.[87]

Beijing Century Joyo Courier Services

Beijing Century Joyo Courier Services is a subsidiary of Amazon and it applied for a freight forwarding license with the US Maritime Commission. Amazon is also building out its logistics in trucking and air freight to potentially compete with UPS and FedEx.[88][89]

Brilliance Audio

Brilliance Audio is an audiobook publisher founded in 1984 by Michael Snodgrass in Grand Haven, Michigan.[90] The company produced its first 8 audio titles in 1985.[90] The company was purchased by Amazon in 2007 for an undisclosed amount.[91][92] At the time of the acquisition, Brilliance was producing 12–15 new titles a month.[92] It operates as an independent company within Amazon.

In 1984, Brilliance Audio invented a technique for recording twice as much on the same cassette.[93] The technique involved recording on each of the two channels of each stereo track.[93] It has been credited with revolutionizing the burgeoning audiobook market in the mid-1980s since it made unabridged books affordable.[93]

ComiXology

ComiXology is a cloud-based digital comics platform with over 200 million comic downloads as of September 2013. It offers a selection of more than 40,000 comic books and graphic novels across Android, iOS, Fire OS and Windows 8 devices and over a web browser. Amazon bought the company in April 2014.[94]

CreateSpace

CreateSpace, which offers self-publishing services for independent content creators, publishers, film studios and music labels became a subsidiary in 2009.[95][96]

Goodreads

Goodreads is a "social cataloging" website founded in December 2006 and launched in January 2007 by Otis Chandler, a software engineer, and entrepreneur, and Elizabeth Chandler. The website allows individuals to freely search Goodreads' extensive user-populated database of books, annotations, and reviews. Users can sign up and register books to generate library catalogs and reading lists. They can also create their own groups of book suggestions and discussions. In December 2007, the site had over 650,000 members and over 10 million books had been added. Amazon bought the company in March 2013.[97]

Lab126

Lab126, developers of integrated consumer electronics such as the Kindle became a subsidiary in 2004.[98]

Shelfari

Shelfari was a social cataloging website for books. Shelfari users built virtual bookshelves of the titles which they owned or had read and they could rate, review, tag and discuss their books. Users could also create groups that other members could join, create discussions and talk about books, or other topics. Recommendations could be sent to friends on the site for what books to read. Amazon bought the company in August 2008.[97] Shelfari continued to function as an independent book social network within the Amazon until January 2016, when Amazon announced that it would be merging Shelfari with Goodreads and closing down Shelfari.[99][100]

Twitch

Twitch is a live streaming platform for video, primarily oriented towards video gaming content. The service was first established as a spin-off of a general-interest streaming service known as Justin.tv. Its prominence was eclipsed by that of Twitch, and Justin.tv was eventually shut down by its parent company in August 2014 in order to focus exclusively on Twitch.[101] Later that month, Twitch was acquired by Amazon for $970 million.[102] Through Twitch, Amazon also owns Curse, Inc., an operator of video gaming communities and a provider of VoIP services for gaming.[103] Since the acquisition, Twitch began to sell games directly through the platform,[104] and began offering special features for Amazon Prime subscribers.[105]

The site's rapid growth had been boosted primarily by the prominence of major esports competitions on the service, leading GameSpot senior esports editor Rod Breslau to have described the service as "the ESPN of esports".[106] As of 2015, the service had over 1.5 million broadcasters and 100 million monthly viewers.[107]

Whole Foods Market

Whole Foods Market is an American supermarket chain exclusively featuring foods without artificial preservatives, colors, flavors, sweeteners, and hydrogenated fats.[108]

On August 23, 2017, it was reported that the Federal Trade Commission approved the merger between Amazon.com and Whole Foods Market.[109] The following day it was announced that the deal would be closed on August 28, 2017.[110]

Junglee

Junglee is a former online shopping service provided by Amazon that enabled customers to search for products from online and offline retailers in India. Junglee started off as a virtual database that was used to extract information off the internet and deliver it to enterprise applications. As it progressed, Junglee started to use its database technology to create a single window marketplace on the internet by making every item from every supplier available for purchase. Web shoppers could locate, compare and transact millions of products from across the Internet shopping mall through one window.[111]

Amazon acquired Junglee in 1998, and the website Junglee.com was launched in India in February 2012[112] as a comparison-shopping website. It curated and enabled searching for a diverse variety of products such as clothing, electronics, toys, jewelry and video games, among others, across thousands of online and offline sellers. Millions of products are browse-able, whereby the client selects a price, and then they are directed to a seller. In November 2017, Amazon closed down Junglee.com and the former domain currently redirects to Amazon India.[113]

Website

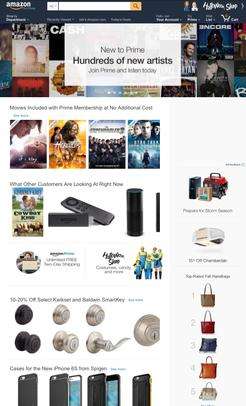

|

Screenshot  amazon.com homepage | |

Type of site | E-commerce |

|---|---|

| Available in | |

| Owner | Amazon.com |

| Website |

amazon |

| Alexa rank |

|

| Commercial | Yes |

| Registration | Optional |

| Launched | 1995 |

| Current status | Online |

| Written in | C++ and Java[115] |

The domain amazon.com attracted at least 615 million visitors annually by 2008.[116] Amazon attracts over 130 million customers to its US website per month by the start of 2016.[117] The company has also invested heavily on a massive amount of server capacity for its website, especially to handle the excessive traffic during the December Christmas holiday season.[118]

Results generated by Amazon's search engine are partly determined by promotional fees.[119]

Amazon's localized storefronts, which differ in selection and prices, are differentiated by top-level domain and country code:

| Region | Sovereignty | Domain name | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | amazon.cn | September 2004 | |

| amazon.in | June 2013 | ||

| amazon.co.jp | November 2000 | ||

| amazon.com.sg | July 2017 | ||

| Europe | amazon.fr | August 2000 | |

| amazon.de | October 1998 | ||

| amazon.it | November 2010 | ||

| amazon.nl | November 2014 | ||

| amazon.es | September 2011 | ||

| amazon.com.tr | September 2018 | ||

| amazon.co.uk | October 1998 | ||

| North America | amazon.ca | June 2002 | |

| amazon.com.mx | August 2013 | ||

| amazon.com | July 1995 | ||

| Oceania | amazon.com.au | November 2013 | |

| South America | amazon.com.br | December 2012 |

Reviews

Amazon allows users to submit reviews to the web page of each product. Reviewers must rate the product on a rating scale from one to five stars. Amazon provides a badging option for reviewers which indicate the real name of the reviewer (based on confirmation of a credit card account) or which indicate that the reviewer is one of the top reviewers by popularity. Customers may comment or vote on the reviews, indicating whether they found a review helpful to them. If a review is given enough "helpful" hits, it appears on the front page of the product. In 2010, Amazon was reported as being the largest single source of Internet consumer reviews.[120]

When publishers asked Bezos why Amazon would publish negative reviews, he defended the practice by claiming that Amazon.com was "taking a different approach ... we want to make every book available—the good, the bad and the ugly ... to let truth loose".[121]

There have been cases of positive reviews being written and posted by public relations companies on behalf of their clients[122] and instances of writers using pseudonyms to leave negative reviews of their rivals' works.

Content search

"Search Inside the Book" is a feature which allows customers to search for keywords in the full text of many books in the catalog.[123][124] The feature started with 120,000 titles (or 33 million pages of text) on October 23, 2003.[125] There are about 300,000 books in the program. Amazon has cooperated with around 130 publishers to allow users to perform these searches.

To avoid copyright violations, Amazon does not return the computer-readable text of the book. Instead, it returns a picture of the matching page, instructs the web browser to disable printing and puts limits on the number of pages in a book a single user can access. Additionally, customers can purchase online access to some of the same books via the "Amazon Upgrade" program.

Third-party sellers

Amazon derives many of its sales (around 40% in 2008) from third-party sellers who sell products on Amazon.[126] Associates receive a commission for referring customers to Amazon by placing links to Amazon on their websites if the referral results in a sale. Worldwide, Amazon has "over 900,000 members" in its affiliate programs.[127] In the middle of 2014, the Amazon Affiliate Program is used by 1.2% of all websites and it is the second most popular advertising network after Google Ads.[128] It is frequently used by websites and non-profits to provide a way for supporters to earn them a commission.[129] Amazon reported over 1.3 million sellers sold products through Amazon's websites in 2007. Unlike eBay, Amazon sellers do not have to maintain separate payment accounts; all payments are handled by Amazon.

Associates can access the Amazon catalog directly on their websites by using the Amazon Web Services (AWS) XML service. A new affiliate product, aStore, allows Associates to embed a subset of Amazon products within another website, or linked to another website. In June 2010, Amazon Seller Product Suggestions was launched (rumored to be internally called "Project Genesis") to provide more transparency to sellers by recommending specific products to third-party sellers to sell on Amazon. Products suggested are based on customers' browsing history.[130]

Amazon sales rank

The Amazon sales rank (ASR) provides an indication of the popularity of a product sold on any Amazon locale. It is a relative indicator of popularity that is updated hourly. Effectively, it is a "best sellers list" for the millions of products stocked by Amazon.[131] While the ASR has no direct effect on the sales of a product, it is used by Amazon to determine which products to include in its bestsellers lists.[131] Products that appear in these lists enjoy additional exposure on the Amazon website and this may lead to an increase in sales. In particular, products that experience large jumps (up or down) in their sales ranks may be included within Amazon's lists of "movers and shakers"; such a listing provides additional exposure that might lead to an increase in sales.[132] For competitive reasons, Amazon does not release actual sales figures to the public. However, Amazon has now begun to release point of sale data via the Nielsen BookScan service to verified authors.[133] While the ASR has been the source of much speculation by publishers, manufacturers, and marketers, Amazon itself does not release the details of its sales rank calculation algorithm. Some companies have analyzed Amazon sales data to generate sales estimates based on the ASR,[134] though Amazon states:

Please keep in mind that our sales rank figures are simply meant to be a guide of general interest for the customer and not definitive sales information for publishers—we assume you have this information regularly from your distribution sources

— Amazon.com Help[135]

Technology

Amazon runs data centers for its online services and owns generators or purchases electricity corresponding to its consumption, mostly renewable energy.[136] Amazon contracted with Avangrid to build and operate the first wind farm in North Carolina to power Amazon's Virginia data centers. The wind farm was built and began operating in December 2016 despite opposition from President Trump and some North Carolina Republican legislators.[137][138][139][140][141]

Amazon records data on customer buyer behavior which enables them to offer or recommend to an individual specific item or bundles of items based upon preferences demonstrated through purchases or items visited.[142]

On May 5, 2014, Amazon unveiled a partnership with Twitter. Twitter users can link their accounts to an Amazon account and automatically add items to their shopping carts by responding to any tweet with an Amazon product link bearing the hashtag #AmazonCart. This allows customers to never leave their Twitter feed and the product is waiting for them when they go to the Amazon website.[143]

Multi-level sales strategy

Amazon employs a multi-level e-commerce strategy. Amazon started by focusing on business-to-consumer relationships between itself and its customers and business-to-business relationships between itself and its suppliers and then moved to facilitate customer-to-customer with the Amazon marketplace which acts as an intermediary to facilitate transactions. The company lets anyone sell nearly anything using its platform. In addition to an affiliate program that lets anyone post-Amazon links and earn a commission on click-through sales, there is now a program which lets those affiliates build entire websites based on Amazon's platform.[144]

Some other large e-commerce sellers use Amazon to sell their products in addition to selling them through their own websites. The sales are processed through Amazon.com and end up at individual sellers for processing and order fulfillment and Amazon leases space for these retailers. Small sellers of used and new goods go to Amazon Marketplace to offer goods at a fixed price.[145] Amazon also employs the use of drop shippers or meta sellers. These are members or entities that advertise goods on Amazon who order these goods direct from other competing websites but usually from other Amazon members. These meta sellers may have millions of products listed, have large transaction numbers and are grouped alongside other less prolific members giving them credibility as just someone who has been in business for a long time. Markup is anywhere from 50% to 100% and sometimes more, these sellers maintain that items are in stock when the opposite is true. As Amazon increases their dominance in the marketplace these drop shippers have become more and more commonplace in recent years.

In November 2015, Amazon opened its first physical bookstore location. It is named Amazon Books and is located in University Village in Seattle. The store is 5,500 square feet and prices for all products match those on its website.[146] Amazon will open its tenth physical book store in 2017;[147] media speculation suggests Amazon plans to eventually roll out 300 to 400 bookstores around the country.[146] Amazon plans to open brick and mortar bookstores in Germany.[148]

Revenue

Amazon.com is primarily a retail site with a sales revenue model; Amazon takes a small percentage of the sale price of each item that is sold through its website while also allowing companies to advertise their products by paying to be listed as featured products.[149]

October 2018 wage increase

After the introduction of the September 5, 2018 'Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies (Stop BEZOS) Act', Amazon announced to its workers on October 2, 2018, that the minimum wage paid to salaried workers be increased to $15 per hour.[150] The wage increase applies to about 350,000 workers. It does not apply to the majority of Amazon's employees who are contract workers. Furthermore, Amazon has also removed some grants and stock options.

Controversies

Since its founding, the company has attracted criticism and controversy from multiple sources over its actions. These include: supplying law enforcement with facial recognition surveillance tools;[151] forming cloud computing partnerships with the CIA;[152] luring customers away from the site's brick and mortar competitors;[153] placing a low priority on warehouse conditions for workers; participating in anti-unionization efforts; remotely deleting content purchased by Amazon Kindle users; taking public subsidies; claiming that its 1-Click technology can be patented; engaging in anti-competitive actions and price discrimination;[154] and reclassifying LGBT books as adult content.[155][156] Criticism has also concerned various decisions over whether to censor or publish content such as the WikiLeaks website, works containing libel and material facilitating dogfight, cockfight, or pedophile activities. In December 2011, Amazon faced a backlash from small businesses for running a one-day deal to promote its new Price Check app. Shoppers who used the app to check prices in a brick-and-mortar store were offered a 5% discount to purchase the same item from Amazon.[157] Companies like Groupon, eBay and Taap.it countered Amazon's promotion by offering $10 off from their products.[158][159] The company has also faced accusations of putting undue pressure on suppliers to maintain and extend its profitability. One effort to squeeze the most vulnerable book publishers was known within the company as the Gazelle Project, after Bezos suggested, according to Brad Stone, "that Amazon should approach these small publishers the way a cheetah would pursue a sickly gazelle."[119] In July 2014, the Federal Trade Commission launched a lawsuit against the company alleging it was promoting in-app purchases to children, which were being transacted without parental consent.[160]

Selling counterfeit items

On October 16, 2016, Apple filed a trademark infringement case against Mobile Star LLC for selling counterfeit Apple products to Amazon. In the suit, Apple provided evidence that Amazon was selling these counterfeit Apple products and advertising them as genuine. Through purchasing, Apple was able to identify that nearly 90% of the Apple accessories sold and fulfilled by Amazon were counterfeit. Amazon was sourcing and selling items without properly determining if they are genuine. Mobile Star LLC settled with Apple for an undisclosed amount on April 27, 2017.[161]

Sales and use taxes

Amazon's state sales tax collection policy has changed over the years since it did not collect any sales taxes in its early years. In the U.S., state and local sales taxes are levied by state and local governments, not at the federal level. In most countries where Amazon operates, a sales tax or value added tax is uniform throughout the country, and Amazon is obliged to collect it from all customers. Proponents of forcing Amazon.com to collect sales tax—at least in states where it maintains a physical presence—argue the corporation wields an anti-competitive advantage over storefront businesses forced to collect sales tax.[162]

Many U.S. states in the 21st century have passed online shopping sales tax laws designed to compel Amazon.com and other e-commerce retailers to collect state and local sales taxes from its customers. Amazon.com originally collected sales tax only from five states as of 2011, but as of April 2017, Amazon collects sales taxes from customers in all 45 states that have a state sales tax and in Washington, D.C.[163]

Comments by President Trump and Senator Sanders

In early 2018, President Donald Trump repeatedly criticized Amazon's use of the United States Postal Service and pricing of its deliveries, stating, "I am right about Amazon costing the United States Post Office massive amounts of money for being their Delivery Boy," Trump tweeted. "Amazon should pay these costs (plus) and not have them bourne [sic] by the American Taxpayer."[164] Amazon's shares fell by 6 percent as a result of Trump's comments. Shepard Smith of Fox News disputed Trump's claims and pointed to evidence that the USPS was offering below market prices to all customers with no advantage to Amazon. However, analyst Tom Forte pointed to the fact that Amazon's payments to the USPS are not public and that their contract has a reputation for being "a sweetheart deal".[165][166]

Throughout the summer of 2018, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders criticized Amazon's wages and working conditions in a series of YouTube videos and media appearances. He also pointed to the fact that Amazon had paid no federal income tax in the previous year.[167] Sanders solicited stories from Amazon warehouse workers who felt exploited by the company.[168] One such story, by James Bloodworth, described the environment as akin to "a low-security prison" and stated that the company's culture used an Orwellian newspeak.[169] These reports cited a finding by New Food Economy that one third of fulfilment center workers in Arizona were on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).[170] Responses by Amazon included incentives for employees to tweet positive stories and a statement which called the salary figures used by Sanders "inaccurate and misleading". The statement also charged that it was inappropriate for him to refer to SNAP as "food stamps".[168] On September 5, 2018, Sanders along with Ro Khanna introduced the Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies (Stop BEZOS) Act aimed at Amazon and other alleged beneficiaries of corporate welfare such as Wal-mart, McDonald's and Uber.[171] Among the bill's supporters were Tucker Carlson of Fox News and Matt Taibbi who criticized himself and other journalists for not covering Amazon's contribution to wealth inequality earlier.[172][173]

Working conditions

Amazon has attracted widespread criticism for poor working conditions by both current employees, who refer to themselves as Amazonians,[174] and former employees,[175][176] as well as the media and politicians. In 2011, it was publicized that at the Breinigsville, Pennsylvania warehouse, workers had to carry out work in 100 °F (38 °C) heat, resulting in employees becoming extremely uncomfortable and suffering from dehydration and collapse. Loading-bay doors were not opened to allow in fresh air, due to the company's concerns over theft.[177] Amazon's initial response was to pay for an ambulance to sit outside on call to cart away overheated employees.[177] The company eventually installed air conditioning at the warehouse.[178]

Some workers, "pickers", who travel the building with a trolley and a handheld scanner "picking" customer orders can walk up to 15 miles during their workday and if they fall behind on their targets, they can be reprimanded. The handheld scanners give real-time information to the employee on how fast or slowly they are working; the scanners also serve to allow Team Leads and Area Managers to track the specific locations of employees and how much "idle time" they gain when not working.[179][180] In a German television report broadcast in February 2013, journalists Diana Löbl and Peter Onneken conducted a covert investigation at the distribution center of Amazon in the town of Bad Hersfeld in the German state of Hessen. The report highlights the behavior of some of the security guards, themselves being employed by a third party company, who apparently either had a neo-Nazi background or deliberately dressed in neo-Nazi apparel and who were intimidating foreign and temporary female workers at its distribution centers. The third party security company involved was delisted by Amazon as a business contact shortly after that report.[181][182][183][184][185]

In March 2015, it was reported in The Verge that Amazon will be removing non-compete clauses of 18 months in length from its US employment contracts for hourly-paid workers, after criticism that it was acting unreasonably in preventing such employees from finding other work. Even short-term temporary workers have to sign contracts that prohibit them from working at any company where they would "directly or indirectly" support any good or service that competes with those they helped support at Amazon, for 18 months after leaving Amazon, even if they are fired or made redundant.[186][187]

A 2015 front-page article in The New York Times profiled several former Amazon employees[188] who together described a "bruising" workplace culture in which workers with illness or other personal crises were pushed out or unfairly evaluated.[9] Bezos responded by writing a Sunday memo to employees,[189] in which he disputed the Times's account of "shockingly callous management practices" that he said would never be tolerated at the company.[9]

In an effort to boost employee morale, on November 2, 2015, Amazon announced that it would be extending six weeks of paid leave for new mothers and fathers. This change includes birth parents and adoptive parents and can be applied in conjunction with existing maternity leave and medical leave for new mothers.[190]

In 2018, investigations by journalists and media outlets such as The Guardian have also exposed poor working conditions at Amazon's fulfillment centers.[191][192]

In response to criticism that Amazon doesn’t pay its workers a livable wage, Jeff Bezos announced beginning November 1, 2018, all U.S. and U.K. Amazon employees will earn a $15 an hour minimum wage.[193] Amazon will also lobby to make $15 an hour the federal minimum wage.[194] At the same time, Amazon also eliminated stock awards and bonuses for hourly employees.[195]

Conflict of interest

In 2013, Amazon secured a US$600 million contract with the CIA, which poses a potential conflict of interest involving the Bezos-owned The Washington Post and his newspaper's coverage of the CIA.[196] Kate Martin, director of the Center for National Security Studies, said, "It's a serious potential conflict of interest for a major newspaper like The Washington Post to have a contractual relationship with the government and the most secret part of the government."[197] This was later followed by a US$10 billion contract with the Department of Defence.[152]

Seattle head tax and houselessness services

In May 2018, Amazon threatened the Seattle City Council over an employee head tax proposal that would have funded houselessness services and low-income housing. The tax would have cost Amazon about $800 per employee, or 0.7% of their average salary.[198] In retaliation, Amazon paused construction on a new building, threatened to limit further investment in the city, and funded a repeal campaign. Although originally passed, the measure was soon repealed after an expensive repeal campaign spearheaded by Amazon.[199]

Facial recognition technology and law enforcement

While Amazon has publicly opposed secret government surveillance, as revealed by Freedom of Information Act requests it has supplied facial recognition support to law enforcement in the form of the "Rekognition" technology and consulting services. Initial testing included the city of Orlando, Florida, and Washington County, Oregon. Amazon offered to connect Washington County with other Amazon government customers interested in Rekognition and a body camera manufacturer. These ventures are opposed by a coalition of civil rights groups with concern that they could lead to expansion of surveillance and be prone to abuse. Specifically, it could automate the identification and tracking of anyone, particularly in the context of potential police body camera integration.[200][201][202] Due to the backlash, the city of Orlando has publicly stated it will no longer use the technology.[203]

Lobbying

Amazon lobbies the United States federal government and state governments on issues such as the enforcement of sales taxes on online sales, transportation safety, privacy and data protection and intellectual property. According to regulatory filings, Amazon.com focuses its lobbying on the United States Congress, the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Reserve. Amazon.com spent roughly $3.5 million, $5 million and $9.5 million on lobbying, in 2013, 2014 and 2015, respectively.[204]

Amazon.com was a corporate member of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) until it dropped membership following protests at its shareholders' meeting on May 24, 2012.[205]

In 2014, Amazon expanded its lobbying practices as it prepared to lobby the Federal Aviation Administration to approve its drone delivery program, hiring the Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld lobbying firm in June.[206] Amazon and its lobbyists have visited with Federal Aviation Administration officials and aviation committees in Washington, D.C. to explain its plans to deliver packages.[207]

Notable businesses founded by former employees

A number of companies have been started and founded by former Amazon employees.[208]

- Findory was founded by Greg Linden.[209]

- Flipkart was founded by Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal.[210]

- Foodista.com was founded by Barnaby Dorfman.[211]

- Hulu was led by Jason Kilar, a former SVP.[212]

- Infibeam was founded by Vishal Mehta.[213]

- Instacart was founded by Apoorva Mehta.[214]

- Jambool and SocialGold were co-founded by Vikas Gupta and Reza Hussein.[210]

- Jet.com was founded by Marc Lore.[210]

- Nimbula was co-founded by Chris Pinkham, a former VP and Willem Van Biljon, a former Product Manager.[215]

- Opscode was co-founded by Jesse Robbins, a former engineer, and manager.[216]

- Pelago was co-founded by Jeff Holden, a former SVP and Darren Vengroff, a former Principal Engineer.[217]

- Pro.com was founded by Matt Williams, former longtime Amazon executive and 'shadow' to Jeff Bezos.[218]

- Quora was co-founded by engineer Charlie Cheever.[219]

- TeachStreet was founded by Dave Schappell, an early product manager.[220]

- The Book Depository was founded by Andrew Crawford; acquired by Amazon in 2011.[221]

- Trusera was founded by Keith Schorsch, an early Amazonian.[222]

- Twilio was founded by Jeff Lawson, a former Technical Product Manager.[210]

- Vittana was founded by Kushal Chakrabarti and Brett Witt.[223]

- Wikinvest was founded by Michael Sha.[224]

See also

- Amazon Breakthrough Novel Award

- Amazon Flexible Payments Service

- Amazon Marketplace

- Amazon Standard Identification Number (ASIN)

- List of book distributors

- Statistically improbable phrases – Amazon.com's phrase extraction technique for indexing books

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "AMAZON.COM, INC. FORM 10-K For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2017" (XBRL). Google Finance. August 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Amazon: number of employees". Statista. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- ↑ Jopson, Barney (July 12, 2011). "Amazon urges California referendum on online tax". Financial Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ↑ Synergy Research Group, Reno, NV. "Microsoft Cloud Revenues Leap; Amazon is Still Way Out in Front – Synergy Research Group". srgresearch.com.

- ↑ "Now you can visit Amazon.de in Dutch". Amazon news. October 4, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Amazon jedną nogą w Polsce". Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Amazon Germany now available in Turkish". November 10, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Amazon.com, Form 10-K, Annual Report, Filing Date Jan 30, 2013" (PDF). SEC database. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Streitfeld, David; Kantor, Jodi (August 17, 2015). "Jeff Bezos Says Amazon Won't Tolerate 'Callous' Management Practices". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ↑ Cheng, Evelyn (September 23, 2016). "Amazon climbs into top 5 biggest US companies by market cap".

- 1 2 Michael J. de la Merced and Nick Wingfield (June 16, 2017). "Amazon to Buy Whole Foods in $13.4 Billion Deal". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Walmart, Amazon expand battlefield in price war".

- ↑ https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/18/amazon-ceo-jeff-bezos-2018-shareholder-letter.html

- ↑ "Amazon - Investor Relations - Annual Reports, Proxies and Shareholder Letters". phx.corporate-ir.net. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- ↑ Davies, Rob (2018-09-04). "Amazon becomes world's second $1tn company". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Amazon hits $1 trillion valuation, second after Apple". CNBC. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Person of the Year – Jeffrey P. Bezos". Time. December 27, 1999. Archived from the original on April 8, 2000. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ↑ "Jeff Bezos: The King of e-Commerce". Entrepreneur.com. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ↑ "AMAZON COM INC (Form: S-1, Received: 03/24/1997 00:00:00)". nasdaq.com. March 24, 1997. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ↑ Amazon's Jeff Bezos: With Jeremy Clarkson, we're entering a new golden age of television Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ↑ Nazaryan, Alexander (July 12, 2016). "How Jeff Bezos is Hurtling Toward World Domination". Newsweek. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ↑ Staff, Writer (June 21, 2014). "Relentless.com". The Economist. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Byers, Ann (2006), Jeff Bezos: the founder of Amazon.com, The Rosen Publishing Group, pp. 46–47, ISBN 9781404207172

- ↑ Murphy Jr., Bill. "'Follow the Money' and Other Lessons From Jeff Bezos".

- ↑ "Amazon Company History". Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ Spiro, Josh. "The Great Leaders Series: Jeff Bezos, Founder of Amazon.com". Inc.com. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ↑ Neate, Rupert (June 22, 2014). "Amazon's Jeff Bezos: the man who wants you to buy everything from his company". The Guardian. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ↑ Tom Metcalf (August 1, 2018). "A hidden Amazon fortune: Bezos' parents may be worth billions". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Rivlin, Gary (July 10, 2005). "A Retail Revolution Turns 10". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Amazon company timeline". Corporate IR. January 2015.

- ↑ Spiro, Josh. "The Great Leaders Series: Jeff Bezos, Founder of Amazon.com".

- ↑ "World's Largest Bookseller Opens on the Web". URLwire. October 4, 1995.

- ↑ "If You Invested in Amazon at Its IPO, You Could Have Been a Millionaire". Fortune. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- 1 2 "Forming a Plan, The Company Is Launched, One Million Titles". Reference for Business: Encyclopedia of Business, 2nd ed. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ↑ Packer, George (February 10, 2014). "Cheap Words". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ↑ Ramo, Joshua Cooper (December 27, 1999). "Jeffrey Preston Bezos: 1999 PERSON OF THE YEAR". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Amazon.com Introduces New Logo; New Design Communicates Customer Satisfaction and A-to-Z Selection". Corporate IR.net. January 5, 2000.

- ↑ Spector, Robert (2002). Amazon.com: Get Big Fast.

- ↑ La Monica, Paul; Isidore, Chris. "Amazon is buying Whole Foods for $13.7 billion". CNN Money. CNNMoney. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ↑ Merced, Michael (June 16, 2017). "Walmart to Buy Bonobos, Men's Wear Company, for $310 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ↑ Press, The Associated (August 23, 2017). "Whole Foods shareholders say yes to Amazon deal". KXAN.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ Johnson, Alex (August 23, 2017). "Amazon's Acquisition of Whole Foods Won't Be Blocked by FTC". NBC News. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ Barron, Richard M. (September 8, 2017). "Triad to take regional approach to Amazon proposal". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ↑ Craver, Richard (October 19, 2017). "Triad woos Amazon in bid for second headquarters". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ↑ Craver, Richard (September 16, 2017). "Triad economic officials prepare to cast long-shot bid for second Amazon headquarters". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ↑ "Amazon donates space in headquarters to Seattle nonprofit | 790 KGMI". 790 KGMI. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ↑ Yurieff, Kaya. "Amazon: We hired 130,000 workers in 2017". CNN Tech.

- ↑ Schlosser, Kurt. "Amazon now employs 566,000 people worldwide — a 66 percent jump from a year ago". GeekWire.

- ↑ Ovide, Shira (2018-08-08). "Amazon Captures 5 Percent of American Retail Spending. Is That a Lot?". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- ↑ "Terms of Service Violation". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- ↑ Stevens, Laura (2018-09-05). "Amazon Orders 20,000 Mercedes-Benz Vans for New Delivery Service". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- 1 2 Day, Matt (January 22, 2018). "Amazon Go cashierless convenience store opens to the public in Seattle". Seattle Times. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ↑ Weise, Elizabeth (January 21, 2018). "Amazon opens its grocery store without a checkout line to the public". USAToday. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ↑ Silver, Curtis (December 5, 2016). "Amazon Announces No-Line Retail Shopping Experience With Amazon Go". Forbes. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Heater, Brian (December 5, 2016). "Amazon launches a beta of Go, a cashier-free, app-based food shopping experience". TechCrunch. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ↑ Garun, Natt (December 5, 2016). "Amazon just launched a cashier-free convenience store". The Verge. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ↑ Leswing, Kif (December 5, 2016). "This is Amazon's grocery store of the future: No cashiers, no registers and no lines". Business Insider. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Hardawar, Devindra (December 5, 2016). "Amazon Go is a grocery store with no checkout lines". Engadget. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Say, My. "Amazon Go Is About Payments, Not Grocery". Forbes. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ↑ Perez, Sarah (August 27, 2018). "Amazon opens its second Amazon Go convenience store". TecgCrunch. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ Day, Matt (August 27, 2018). "Amazon has a second Go at cashierless convenience store in downtown Seattle". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ "Amazon's new retail store only stocks items rated 4 stars and up". Engadget. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ Thomas, Lauren (2018-09-26). "Amazon is opening a new store that sells items from its website rated 4 stars and above". CNBC. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ "Amazon's new store only sells products with 4-star ratings and above". The Verge. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ "Modi effect: Amazon to pour additional $3 billion into India, says Jeff Bezos". June 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Amazon India Investments". Quartz. July 30, 2014.

- ↑ Domainnamewire.com (September 14, 2014). "Wow: Amazon.com buys .Buy for $4.6 million, .Tech sells for $6.8 million".

- ↑ ".Buy Domain Sold to Amazon.com for $4,588,888". Uttamujjwal. September 2014. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ↑ Olsen, Stefanie (July 14, 2008). "Amazon invests in Engine Yard's cloud computing". News.cnet.com. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ↑ Isaac, Mike (December 2, 2010). "LivingSocial Receives $175 Million Investment From Amazon". Forbes. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Officers & Directors". Amazon. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- ↑ E-Commerce Times: Toys 'R' Us wins right to end Amazon partnership., March 3, 2006

- ↑ Oswald, Diane (May 27, 2008). "Borders Returns to Online Sales, Drops Amazon". International Business Times.

- ↑ "Target Launches Redesigned E-Commerce Website". Target Corporation. August 23, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ↑ Streitfeld, David (October 18, 2011). "Bookstores Drop Comics After Amazon Deal With DC". The New York Times.

- ↑ Barr, Alistair (November 11, 2013). "Amazon starts Sunday delivery with US Postal Service". USA Today. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ↑ Lardinois, Frederic. "Amazon partners with U.K. government to test its drones" (July 26, 2016).

- ↑ "Nike confirms 'pilot' partnership with Amazon". Engadget. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ↑ Wattles, Jackie (June 29, 2017). "Nike confirms Amazon partnership". CNNMoney. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ↑ Wahba, Phil. "Nike confirms it will sell directly on Amazon and Instagram". Fortune. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ↑ "Booths teams up with Amazon to sell down South for the first time". Telegraph. October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- ↑ Bhumika, Khatri (27 September 2018). "Amazon's JV Appario Retail Clocks In $104.4 Mn For FY18". Inc42 Media.

- ↑ Zacks Investment Research "Is Amazon.com, Inc. (AMZN) Eyeing the Indian Grocery Market Next?" March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ↑ "Amazon Jobs – Work for a Subsidiary". Archived from the original on August 1, 2014. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ↑ McCracken, Harry, "Amazon's A9 Search as We Knew It: Dead!", PC World. September 29, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ↑ Steele, B., Amazon is now managing its own ocean freight, engadget.com, January 27, 2017, accessed January 29, 2017

- ↑ Sayer, Peter (January 31, 2008). "Amazon buys Audible for US$300 million". PC World.

- ↑ "Is Logistics About To Get Amazon'ed?". TechCrunch. AOL. January 29, 2016.

- ↑ David Z. Morris (January 14, 2016). "Amazon China Has Its Ocean Shipping License – Fortune". Fortune.

- 1 2 "Company Overview". Brilliance Audio. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ "amazon.com Acquires Brilliance Audio". Taume News. May 27, 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2007. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- 1 2 Staci D. Kramer (May 23, 2007). "Amazon Acquires Audiobook Indie Brilliance Audio". Gigaom. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Virgil L. P. Blake (1990). "Something New Has Been Added: Aural Literacy and Libraries". Information Literacies for the Twenty-First Century. G. K. Hall & Co. pp. 203–218.

- ↑ Stone, Brad (April 11, 2014). "Amazon Buys ComiXology, Takes Over Digital Leadership". Bloomberg BusinessWeek.

- ↑ "Independent Publishing with CreateSpace". CreateSpace: An Amazon Company. Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ↑ "About CreateSpace : History". CreateSpace: An Amazon Company. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- 1 2 Kaufman, Leslie (March 28, 2013). "Amazon to Buy Goodreads". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Amazon research unit Lab 126 agrees to big lease that could bring Sunnyvale 2,600 new workers". Retrieved August 21, 2016.

- ↑ jenp27 (January 12, 2016). "Amazon Kills Shelfari". The Reader's Room. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ Holiday, J.D. (January 13, 2016). "Shelfari Is Closing! BUT, You Can Merge Your Account with Goodreads!". The Book Marketing Network.

- ↑ "Twitch pulls the plug on video-streaming site Justin.tv". CNET. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ Welch, Chris (August 25, 2014). "Amazon, not Google, is buying Twitch for $970 million". The Verge. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ Hall, Charlie (August 16, 2016). "Twitch to acquire Curse". Polygon. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ McCormick, Rich (February 27, 2017). "Twitch will start selling games and giving its streamers a cut". The Verge. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ Statt, Nick (September 30, 2016). "Twitch will be ad-free for all Amazon Prime subscribers". The Verge. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ Popper, Ben (September 30, 2013). "Field of streams: how Twitch made video games a spectator sport". The Verge. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ Needleman, Sarah E. (January 29, 2015). "Twitch's Viewers Reach 100 Million a Month". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Quality Standards". Whole Foods Market.

- ↑ Bhattarai, Abha (August 23, 2017). "FTC clears Amazon.com purchase of Whole Foods". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Amazon and Whole Foods Market Announce Acquisition to Close This Monday, Will Work Together to Make High-Quality, Natural and Organic Food Affordable for Everyone". Amazon.com. BUSINESS WIRE. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Junglee boys strike gold on the net". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013.

- ↑ "Amazon Launches Online Shopping Service In India". reuters.com. February 2, 2012.

- ↑ "Amazon brings the curtains down on Junglee.com, finally". vccircle.com. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Amazon.com Site Info". Alexa Internet. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ↑ Lextrait, Vincent (January 2010). "The Programming Languages Beacon, v10.0". Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ↑ SnapShot of amazon.com, amazonellers.com, walmart.com. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ↑ "SnapShot of amazon.com – Compete". Siteanalytics.compete.com. Retrieved March 24, 2016.

- ↑ Pepitone, Julianne (December 9, 2010). "Why attackers can't take down Amazon.com". CNN. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

Amazon has famously massive server capacity in order to handle the December e-commerce rush. That short holiday shopping window is so critical and so intense, that even a few minutes of downtime could cost Amazon millions.

- 1 2 Packer, George (February 17, 2014). "Cheap Words". newyorker.com. Retrieved March 22, 2014.

- ↑ "2010 Social Shopping Study Reveals Changes in Consumers' Online Shopping Habits and Usage of Customer Reviews" (Press release). the e-tailing group, PowerReviews. May 3, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2013 – via Business Wire.

- ↑ Spector, Robert (2002). Amazon.com. p. 132.

- ↑ "BEACON SPOTLIGHT: Amazon.com rave book reviews – too good to be true?". The Cincinnati Beacon. May 25, 2010. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Amazon's online reader Search Inside reference". Amazon.com. September 9, 2009. Archived from the original on August 28, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Search Inside reference". Amazon.com. September 9, 2009. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ↑ Ward, Eric (October 23, 2003). "Amazon.com Launches "Search Inside the Book" Feature". Urlwire.com. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ↑ "AMAZON ENTERS THE CLOUD COMPUTING BUSINESS" (PDF). Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Amazon.co.uk Associates: The web's most popular and successful Affiliate Program". Affiliate-program.amazon.co.uk. July 9, 2010. Archived from the original on August 26, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ↑ "Usage of advertising networks for websites". W3Techs.com. July 22, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ↑ "14 Easy Fundraising Ideas for Non-Profits". blisstree.com. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ↑ "Amazon Seller Product Suggestions". Amazonservices.com. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- 1 2 "Amazon FAQ". Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Amazon.com Movers and shakers". Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Amazon.com Author Central". Retrieved September 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Amazon Sales Estimator". Jungle Scout. May 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about Amazon.com". Amazon.com. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Sustainability-Energy and Environment". Amazon.com. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Amazon Wind Farm US East completed in North Carolina". Electric Light & Power. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ↑ "Trump plea fails to block Amazon's North Carolina wind farm". Datacenter Dynamics. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ↑ Mearian, Lucas. "N.C. wind farm goes live despite legislators' claims it's a national security threat". Computer World. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ↑ Ohnesorge, Lauren K. (February 10, 2017). "Amazon wind farm developer: We plan to invest in more N.C. renewables projects". Triangle Business Journal.

- ↑ "Navy: Wind farm opposed by GOP lawmakers won't harm radar". Navy Times. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ↑ "How Amazon Works". Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ↑ Cheng, Roger (May 5, 2014). "Amazon, Twitter link up for easy shopping through #AmazonCart". CNET. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- ↑ "How Amazon Works". Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ↑ "Help". Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- 1 2 "Passing Comment On Possible Bookstore Plans by Amazon.com Creates Internet Imbroglio – CoStar Group". www.costar.com. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ↑ Rey, Jason Del (March 8, 2017). "Amazon just confirmed its 10th book store, signaling this is way more than an experiment". Recode.

- ↑ "Einzelhandel: Amazon plant Offline-Filialen in Deutschland". Retrieved June 4, 2018 – via www.faz.net.

- ↑ "SWOT Analysis Amazon". Archived from the original on December 3, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ↑ https://www.democracynow.org/2018/10/12/rep_ro_khanna_introduces_internet_bill

- ↑ "Amazon is selling facial recognition to law enforcement — for a fistful of dollars". May 22, 2018.

- 1 2 Jeong, May (2018-08-13). ""Everybody immediately knew that it was for Amazon": Has Bezos become more powerful in DC than Trump?". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ↑ Leiber, Nick (December 7, 2011). "Amazon Lure's Shoppers Away from Stores". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ↑ Baum, Andrew (October 23, 2015). "Amazon Wins Ruling on Results for Searches on Brands It Doesn't Sell". The National Law Review. Foley & Lardner. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ Slatterly, Brennon. "Amazon 'Glitch' Yanks Sales Rank of Hundreds of LGBT Books". PC World. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ↑ Armstrong, Paul (November 28, 2000). "Amazon: 'Glitch' caused gay censorship error". CNN. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ↑ Raice, Shayndi (December 20, 2011). "Groupon Launches Anti-Amazon Promotion of Sorts". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "Focus on Mobile Commerce – While some still cry, others fight back". Internet Retailer. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "What can retailers learn from Amazon, Groupon and eBay? – Mobile Commerce Daily – Multichannel retail support". Mobile Commerce Daily. December 20, 2011. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Complaint, Federal Trade Commission v. Amazon.com, Inc" (PDF). PacerMonitor. PacerMonitor. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Apple Sues Mobile Star for Selling Counterfeit Power Adapters and Charging Cables through Amazon". Patently Apple.

- ↑ Milchen, Jeff (April 28, 2011). "To Help Main Street, Close the Internet Sales Tax Loophole". Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ↑ "Amazon will start collecting sales tax nationwide starting April 1st". The Verge. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ↑ Franck, Thomas (April 3, 2018). "Amazon shares turn negative after Trump bashes company for a fourth time in a week". CNBC. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters. "Amazon shares fall 6 percent as Trump renews attack". U.S. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ Manchester, Julia. "Fox's Shep Smith fact-checks Trump's Amazon claims: 'None of that was true'". The Hill. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ Wohlfeil, Samantha (2018-09-06). "Workers describe pressures at Amazon warehouses as Bernie Sanders gears up to make the corporation pay". Inlander. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- 1 2 Matsakis, Louise (2018-09-06). "The truth about Amazon, food stamps and tax breaks". Wired. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- ↑ Bloodworth, James (2018-09-17). "I worked in an Amazon warehouse. Bernie Sanders is right to target them". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- ↑ Robertson, Adi (2018-09-05). "Bernie Sanders introduces "Stop BEZOS" bill to tax Amazon for underpaying workers". The Verge. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ↑ Gibson, Kate (2018-09-05). "Bernie Sanders targets Amazon, Walmart with 100% tax". CBS. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ↑ Delaney, Arthur (2018-08-31). "Why Bernie Sanders and Tucker Carlson agree on food stamps". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ↑ Taibbi, Matt (2018-09-18). "Bernie Sanders' Anti-Amazon Bill is an Indictment of the Media, Too". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- ↑ An Amazonian's response to "Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace" August 16, 2015

- ↑ Amazon under fire for staffing practices in Randstad contract|Business intelligence for recruitment and resourcing professionals Archived August 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.. Recruiter.co.uk (August 2, 2013). Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Brutal Conditions In Amazon's Warehouse's Threaten To Ruin The Company's Image,". Business Insider. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- 1 2 Soper, Spencer (September 18, 2011). "Inside Amazon's Warehouse". The Morning Call. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ Soper, Spencer; Kraus, Scott (September 25, 2011). "Amazon gets heat over warehouse". Morning Call. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ Yarrow, Jay; Kovach, Steve (September 20, 2011). "10 Crazy Rules That Could Get You Fired From Amazon Warehouses". Business Insider. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ O'Connor, Sarah (February 8, 2013). "Amazon unpacked". Financial Times. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Kritik an Arbeitsbedingungen bei Amazon". tagesschau.de. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Ausgeliefert! Leiharbeiter ... – Ausgeliefert! Leiharbeiter bei Amazon – Reportage & Documentation – ARD | Das Erste". Daserste.de. February 13, 2013. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ Paterson, Tony (February 14, 2013). "Amazon 'used neo-Nazi guards to keep immigrant workforce under control' in Germany – Europe – World". The Independent. London. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Germany to probe claims of staff abuse". Globaltimes.cn. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Amazon to investigate reports temporary staff in Germany were mistreated". Globalnews.ca. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ Woodman, Spencer (March 26, 2015). "Exclusive: Amazon makes even temporary warehouse workers sign 18-month non-competes". The Verge. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ↑ Kasperkevic, Jana (March 27, 2015). "Amazon to remove non-compete clause from contracts for hourly workers". The Guardian. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ↑ Kantor, Jodi; Streitfeld, David (August 15, 2015). "Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015.

- ↑ Cook, John (November 8, 2017). "Full memo: Jeff Bezos responds to brutal NYT story, says it doesn't represent the Amazon he leads". GeekWire. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Amazon increases paid leave for new parents". The Seattle Times. November 2, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ↑ Picchi, Aimee (April 19, 2018). "Inside an Amazon warehouse: "Treating human beings as robots"". CBS MoneyWatch. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ↑ Sainato, Michael (July 30, 2018). "Accidents at Amazon: workers left to suffer after warehouse injuries". The Guardian. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ↑ https://abcnews.go.com/US/amazon-raise-companys-minimum-wage-15-employees/story?id=58225644

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/oct/02/amazon-raises-minimum-wage-us-uk-employees

- ↑ Soper, Spencer (October 3, 2018). "Amazon Warehouse Workers Lose Bonuses, Stock Awards for Raises". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ↑ "The CIA, Amazon, Bezos and the Washington Post : An Exchange with Executive Editor Martin Baron". The Huffington Post. January 8, 2014.

- ↑ Streitfeld, David; Haughney, Christine (August 18, 2013). "Expecting the Unexpected From Jeff Bezos". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Amazon puts high-profile Seattle plans on ice over proposal to tax large employers". The Seattle Times. May 2, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- ↑ "'Show of force': Business-backed opponents of Seattle head tax outspent supporters 2 to 1". The Seattle Times. July 13, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Amazon is selling facial recognition to law enforcement — for a fistful of dollars". May 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Yes, Amazon is tracking people".

- ↑ "Amazon Teams Up With Government to Deploy Dangerous New Facial Recognition Technology".

- ↑ "Orlando Stops Using Amazon's Face-Scanning Tech Amid Spying Concerns". June 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Amazon's Lobbying Expenditures".

- ↑ Parkhurst, Emily (May 24, 2012). "Amazon shareholders met by protesters, company cuts ties with ALEC".

- ↑ Romm, Tony. "In Amazon's shopping cart: D.C. influence". www.politico.com. Politico. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ↑ Kang, Cecilia. "F.A.A. Drone Laws Start to Clash With Stricter Local Rules". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2015.

- ↑ Malik, Om (November 21, 2008). "The Growing Ex-Amazon Club and Why It's a Good Thing". GigaOM.

- ↑ Bishop, Todd (April 8, 2004). "Real glut buster: Web site helps sift news". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- 1 2 3 4 D'Onfro, Jillian (June 20, 2015). "13 interesting startups founded by ex-Amazon employees". Business Insider. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Foodista Raises $550,000 From Amazon And Other Angels". TechCrunch.

- ↑ Chaparro, Frank (September 28, 2017). "A guy who helped revolutionize Amazon explains what the future of finance looks like". Business Insider. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Sruthijith, KK (January 28, 2010). "Indian innovation to give Amazon's Kindle run for its money". The Economic Times. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Lien, Tracey (January 27, 2017). "Apoorva Mehta had 20 failed start-ups before Instacart". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Darrow, Barb. "One of Twitter's Top Engineers Left the Company Last Month". Fortune.

- ↑ Jesse Robbins; Kripa Krishnan; John Allspaw; Tom Limoncelli (September 12, 2012). "Resilience Engineering: Learning to Embrace Failure". ACM Queue.

- ↑ "Give it a Whrrl: Service blends Net, friends' advice". ABC News. November 12, 2007. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Former Digg CEO Matt Williams Launches Pro.com To Connect Homeowners With Nearby Contractors". Tech Crunch. May 13, 2014.

- ↑ Hardy, Quentin. "What Does Quora Know?". Forbes.

- ↑ Dudley, Brier (February 5, 2012). "TeachStreet leaves some lessons as it shuts down". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Help at Book Depository". BookDepository.com. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ↑ Dudley, Brier (June 16, 2008). "Ex-Amazon GM launches Trusera social health info network". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ Heim, Kristi (July 28, 2009). "Amazon.com veterans back Vittana educational loans". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ↑ "WIKINVEST: Social stock picking and analysis". Wired.

Further reading

- Brandt, Richard L. (2011). One Click: Jeff Bezos and the Rise of Amazon.com. New York: Portfolio Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59184-375-7.

- Daisey, Mike (2002). 21 Dog Years. Free Press. ISBN 0-7432-2580-5.

- Friedman, Mara (2004). Amazon.com for Dummies. Wiley Publishing. ISBN 0-7645-5840-4.

- Marcus, James (2004). Amazonia: Five Years at the Epicenter of the Dot.Com Juggernaut. W. W. Norton. ISBN 1-56584-870-5.

- Spector, Robert (2000). Amazon.com – Get Big Fast: Inside the Revolutionary Business Model That Changed the World. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-662041-4.

- Stone, Brad (2013). The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon. New York: Little Brown and Co. ISBN 978-0-316-21926-6. OCLC 856249407.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amazon.com. |

- Business data for Amazon.com, Inc.: Google Finance

- Yahoo! Finance

- Bloomberg

- Reuters

- SEC filings