Low German

| Low German | |

|---|---|

| Low Saxon | |

|

Plattdütsch, Plattdüütsch, Plattdütsk, Plattdüütsk, Plattduitsk (South-Westphalian), Plattduitsch (Eastphalian), Plattdietsch (Prussian) German: Plattdeutsch, NiederdeutschDutch: Nederduits | |

| Native to |

Northern Germany Western Germany Eastern Netherlands Southern Denmark |

| Ethnicity |

Dutch, Frisians and Germans; Historically Saxons (Germanic peoples and modern regional subgroup of Germans) |

Native speakers |

Estimated 6.7 million[lower-alpha 1][1][2] Up to 10 million second-language speakers (2001)[3] |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

nds |

| ISO 639-3 |

nds (Dutch varieties and Westphalian have separate codes) |

| Glottolog |

lowg1239 Low German[10] |

| Linguasphere |

52-ACB |

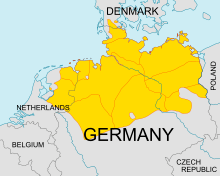

Approximate area in which Low German/Low Saxon dialects are spoken in Europe (after the expulsion of Germans). | |

Low German or Low Saxon (Low German of Germany: Plattdüütsch or Neddersassisch; Low Saxon of the Netherlands: Nedersaksies; German: Niederdeutsch, Plattdeutsch, or Niedersächsisch; Dutch: Nederduits; (also other dialectal variants)) is a West Germanic language spoken mainly in Northern Germany and the northeastern part of the Netherlands. It is also spoken to a lesser extent in the German diaspora worldwide (e.g. Plautdietsch).

Low German is most closely related to Frisian and English, with which it forms the Ingvaeonic group of the West Germanic languages. Like Dutch (Istvaeonic), it is spoken north of the Benrath and Uerdingen isoglosses, while (Standard) German (Irminonic) is spoken south of those lines. Like Frisian, English, Dutch and the North Germanic languages, Low German has not undergone the High German consonant shift, as opposed to German.

The Low German dialects spoken in the Netherlands are mostly referred to as Low Saxon, those spoken in northwestern Germany (Lower Saxony, Westphalia, Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg, and Bremen) as either Low German or Low Saxon, and those spoken in northeastern Germany mostly as Low German. This is because northwestern Germany and the northeastern Netherlands were the area of settlement of the Saxons, while Low German spread to northeastern Germany through eastward migration of Low German-speakers.

It has been estimated that Low German has approximately 6.7 million native speakers – 5 million in Germany, primarily Northern Germany,[1] and 1.7 million in the Netherlands.[2] A 2005 study by H. Bloemhof, Taaltelling Nedersaksisch, showed 1.8 million spoke it daily in the Netherlands.[11]

Geographical extent

Inside Europe

It has been estimated that Low German has approximately 6.7 million native speakers – 5 million in Germany, primarily Northern Germany,[1] and 1.7 million in the Netherlands.[2]

Dialects of Low German are spoken in the northeastern area of the Netherlands (Dutch Low Saxon) and are written there with an unstandardised orthography based on Standard Dutch orthography. The position of the language is according to UNESCO vulnerable.[12] Between 1995 and 2011 the numbers of speakers of parents dropped from 34% in 1995 to 15% in 2011. Numbers of speakers of their children dropped in the same period from 8% to 2%.[13]

Variants of Low German are spoken in most parts of Northern Germany, for instance in the states of Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, Hamburg, Bremen, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saxony-Anhalt, and Brandenburg. Small portions of northern Hesse and northern Thuringia are traditionally Low Saxon-speaking too. Historically, Low German was also spoken in formerly German parts of Poland as well as in East Prussia and the Baltic States of Estonia and Latvia. The Baltic Germans spoke a distinct Low German dialect, which has influenced the vocabulary and phonetics of both Estonian and Latvian languages. The historical Sprachraum of Low German also included contemporary northern Poland, East Prussia (the modern Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia), a part of western Lithuania, and the German communities in the Baltic states, most notably the Hanseatic cities of modern Latvia and Estonia. German speakers in this area fled the Red Army or were forcibly expelled after the border changes at the end of World War II.

The language was also formerly spoken in the outer areas of what is now the city-state of Berlin, but in the course of urbanisation and national centralisation in that city, the language has vanished (the Berlin dialect itself is a northern outpost of High German). Under the name Low Saxon, there are speakers in the Dutch north-eastern provinces of Groningen, Drenthe, Stellingwerf (part of Friesland), Overijssel, and Gelderland, in several dialect groups per province.

Today, there are still speakers outside Germany and the Netherlands to be found in the coastal areas of present-day Poland (minority of ethnic German East Pomeranian speakers who were not expelled from Pomerania, as well as the regions around Braniewo). In the Southern Jutland region of Denmark there may still be some Low German speakers in some German minority communities, but the Low German and North Frisian dialects of Denmark can be considered moribund at this time.

Outside Europe and the Mennonites

There are also immigrant communities where Low German is spoken in the Western hemisphere, including Canada, the United States, Mexico, Belize, Venezuela, Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay. In some of these countries, the language is part of the Mennonite religion and culture.[14] There are Mennonite communities in Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Kansas and Minnesota which use Low German in their religious services and communities. These Mennonites are descended from primarily Dutch settlers that had initially settled in the Vistula delta region of Prussia in the 16th and 17th centuries before moving to newly-acquired Russian territories in Ukraine in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and then to the Americas in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The types of Low German spoken in these communities and in the Midwest region of the United States have diverged since emigration. The survival of the language is tenuous in many places, and has died out in many places where assimilation has occurred. Members and friends of the Historical Society of North German Settlements in Western New York (Bergholz, NY), a community of Lutherans who trace their immigration from Pomerania in the 1840s, hold quarterly "Plattdeutsch lunch" events, where remaining speakers of the language gather to share and preserve the dialect. Mennonite colonies in Paraguay, Belize, and Chihuahua, Mexico have made Low German a "co-official language" of the community.

East Pomeranian is also spoken in parts of Southern and Southeastern Brazil, in the latter especially in the state of Espírito Santo, being official in five municipalities, and spoken among its ethnically European migrants elsewhere, primarily in the states of Rio de Janeiro and Rondônia. East Pomeranian-speaking regions of Southern Brazil are often assimilated into the general German Brazilian population and culture, for example celebrating the Oktoberfest, and there can even be a language shift from it to Riograndenser Hunsrückisch in some areas. In Espírito Santo, nevertheless, Pomeranian Brazilians are more often proud of their language, and particular religious traditions and culture,[16] and not uncommonly inheriting the nationalism of their ancestors, being more likely to accept marriages of its members with Brazilians of origins other than a Germanic Central European one than to assimilate with Brazilians of Swiss, Austrian, Czech, and non-East Pomeranian-speaking German and Prussian heritage – that were much more numerous immigrants to both Brazilian regions (and whose language almost faded out in the latter, due to assimilation and internal migration), by themselves less numerous than the Italian ones (with only Venetian communities in areas of highly Venetian presence conserving Talian, and other Italian languages and dialects fading out elsewhere).

| Speakers of low German outside Europe | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nomenclature

There are different uses of the term "Low German":

- A specific name of any West Germanic varieties that neither have taken part in the High German consonant shift nor classify as Low Franconian or Anglo-Frisian; this is the scope discussed in this article.

- A broader term for the closely related, continental West Germanic languages unaffected by the High German consonant shift, nor classifying as Anglo-Frisian, and thus including Low Franconian varieties spoken in Germany such as Kleverlandish, but not those in the Netherlands, thus excluding Dutch.

In Germany, native speakers of Low German call their language Platt, Plattdüütsch or Nedderdüütsch. In the Netherlands, native speakers refer to their language as dialect, plat, nedersaksies, or the name of their village, town or district.

Officially, Low German is called Niederdeutsch (Nether or Low German) by the German authorities and Nedersaksisch (Nether or Low Saxon) by the Dutch authorities. Plattdeutsch, Niederdeutsch and Platduits, Nedersaksisch are seen in linguistic texts from the German and Dutch linguistic communities respectively.

In Danish it is called Plattysk, Nedertysk or, rarely, Lavtysk. Mennonite Low German is called Plautdietsch.

"Low" refers to the flat plains and coastal area of the northern European lowlands, contrasted with the mountainous areas of central and southern Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, where High German (Highland German) is spoken.[19] Etymologically however, Platt meant "clear" in the sense of a language the simple people could understand. In Dutch and German, the word Plat can also mean "improper", "rude" or "too simple" which is why the term is not popular in the Netherlands.

The colloquial term Platt denotes both Low German dialects and any non-standard Western variety of German; this use is chiefly found in northern and Western Germany and is not considered to be linguistically correct.[20]

The ISO 639-2 language code for Low German (Low Saxon) has been nds (niedersächsisch or nedersaksisch, neddersassisch) since May 2000.

Classification

Low German is a part of the continental West Germanic dialect continuum. To the West, it blends into the Low Franconian languages, including Dutch. A distinguishing feature between the Southern Low Franconian varieties and Low German varieties is the plural of the verbs. Low German varieties have a common verbal plural ending, whereas Southern Low Franconian varieties have a different form for the second person plural. Northern Low Franconian varieties, including standard Dutch, have also developed a common verbal plural ending.

To the South, Low German blends into the High German dialects of Central German that have been affected by the High German consonant shift. The division is usually drawn at the Benrath line that traces the maken – machen isogloss.

To the East, it abuts the Kashubian language (the only remnant of the Pomeranian language) and, since the expulsion of nearly all Germans from the Polish part of Pomerania following the Second World War, also by the Polish language. East Pomeranian and Central Pomeranian are dialects of Low German.

To the North and Northwest, it abuts the Danish and the Frisian languages. Note that in Germany, Low German has replaced the Frisian languages in many regions. Saterland Frisian is the only remnant of East Frisian language and is surrounded by Low German, as are the few remaining North Frisian varieties, and the Low German dialects of those regions have influences from Frisian substrates.

Some classify the northern dialects of Low German together with English and Frisian as the North Sea Germanic or Ingvaeonic languages. However, most exclude Low German from that group often called Anglo-Frisian languages because some distinctive features of that group of languages are only partially observed in Low German, for instance the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law (some dialects have us, os for "us" whereas others have uns, ons), and because other distinctive features do not occur in Low German at all, for instance the palatalization of /k/ (compare palatalized forms such as English cheese, Frisian tsiis to non-palatalized forms such as Low German Kees or Kaise, Dutch kaas, German Käse).

A language or a mere dialect?

The question of whether Low German, as spoken today, should be considered a separate language, rather than a dialect of German or even Dutch, has been a point of contention. Linguistics offers no simple, generally accepted criterion to decide this question.

Scholarly arguments have been put forward in favour of classifying Low German as a German dialect.[21] As said, these arguments are not linguistic but rather socio-political and build mainly around the fact that Low German has no official standard form or use in sophisticated media. The situation of Low German may thus be considered a "pseudo-dialectized abstand language" ("scheindialektisierte Abstandsprache").[22] In contrast, Old Saxon and Middle Low German are generally considered separate languages in their own rights. Since Low German has undergone a strong decline since the 18th century, the perceived similarities with High German or Dutch may often be direct adaptations from the dominating standard language, resulting in a growing incapability of speakers to speak correctly what was once Low German proper.[23]

Others have argued for the independence of today's Low German dialects, taken as continuous outflow of the Old Saxon and Middle Low German tradition.[24]

Legal status

Low German has been recognized by the Netherlands and by Germany (since 1999) as a regional language according to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Within the official terminology defined in the charter, this status would not be available to a dialect of an official language (as per article 1a), and hence not to Low German in Germany if it were considered a dialect of German. Advocates of the promotion of Low German have expressed considerable hope that this political development will at once lend legitimacy to their claim that Low German is a separate language, and help mitigate the functional limits of the language that may still be cited as objective criteria for a mere dialect (such as the virtually complete absence from legal and administrative contexts, schools, the media, etc.).[25]

At the request of Schleswig-Holstein, the German government has declared Low German as a regional language. German offices in Schleswig-Holstein are obliged to accept and handle applications in Low German on the same footing as Standard High German applications.[26] The Bundesgerichtshof ruled in a case that this was even to be done at the patent office in Munich, in a non–Low German region, when the applicant then had to pay the charge for a translator,[27] because applications in Low German are considered "nicht in deutscher Sprache abgefasst" (not written in the German language).

Varieties of Low German

In Germany

- West Low German

- East Low German

- Brandenburgisch

- Mecklenburgisch-Vorpommersch

- Mittelpommersch

- East Pomeranian

- Low Prussian

- Plautdietsch (Mennonite Low German, used also in many other countries)

In the Netherlands

The Dutch Low Saxon varieties, which are also defined as Dutch dialects, consist of:

- Gronings and Noord-Drents

- Hogelandsters

- Oldambtsters

- Stadsgronings

- Veenkoloniaals

- Westerkwartiers

- Kollumerpompsters

- Kollumerlands

- Middaglands

- Midden-Westerkwartiers

- Zuid-Westerkwartiers

- Westerwolds

- Stellingwerfs

- Drents

- Twents

- Twents-Graafschaps

- Twents

- Gelders-Overijssels

- Achterhoeks

- Sallands

- Oost-Veluws (partly classified as Veluws)

- Urkers

- Veluws

- Oost-Veluws (partly classified as Gelders-Overijssels)

- West-Veluws

History

Old Saxon

Old Saxon, also known as Old Low German, is a West Germanic language. It is documented from the 9th century until the 12th century, when it evolved into Middle Low German. It was spoken on the north-west coast of Germany and in Denmark (Schleswig-Holstein) by Saxon peoples. It is closely related to Old Anglo-Frisian (Old Frisian, Old English), partially participating in the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law.

Only a few texts survive, predominantly in baptismal vows the Saxons were required to perform at the behest of Charlemagne. The only literary texts preserved are Heliand and the Old Saxon Genesis.

Middle Low German

The Middle Low German language is an ancestor of modern Low German. It was spoken from about 1100 to 1600. The neighbouring languages within the dialect continuum of the West Germanic languages were Middle Dutch in the West and Middle High German in the South, later substituted by Early New High German. Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League, spoken all around the North Sea and the Baltic Sea.[28] It had a significant influence on the Scandinavian languages. Based on the language of Lübeck, a standardized written language was developing, though it was never codified.

Contemporary

There is a distinction between the German and the Dutch Low Saxon/Low German situation.

Germany

After mass education in Germany in the 19th and 20th centuries, the slow decline which Low German had been experiencing since the end of the Hanseatic League turned into a free fall. The decision to exclude Low German in formal education was not without controversy, however. On one hand, proponents of Low German advocated that since it had a strong cultural and historical value and was the native language of students in northern Germany, it had a place in the classroom. On the other hand, High German was considered the language of education, science, and national unity, and since schools promoted these values, High German was seen as the best candidate for the language of instruction.[29]

Initially, regional languages and dialects were thought to limit the intellectual ability of their speakers. Because of Low German’s archaic features and constructions, historical linguists considered it “backwards.” It wasn’t until the efforts of proponents such as Klaus Groth that this impression changed. Groth’s publications demonstrated that Low German was a valuable language in its own right, and he was able to convince others that Low German was suitable for literary arts and was a national treasure worth keeping.[29]

Through the works of advocates like Groth, both proponents and opponents of Low German in formal education saw the language’s innate value as the cultural and historical language of northern Germany. Nevertheless, the opponents claimed that it should simply remain a spoken and informal language to be used on the street and in the home, but not in formal schooling. According to them, it simply did not match the nationally unifying power of High German. As a result, while Low German literature was deemed worthy of being taught in school, High German was chosen as the language of scholarly instruction. With High German the language of education and Low German the language of the home and daily life, a stable diglossia developed in Northern Germany.[29] Various Low German dialects are understood by 10 million people, but many fewer are native speakers. Total users in all countries are 301,000.[30]

The KDE project supports Low German (nds) as a language for its computer desktop environment,[31] as does the GNOME Desktop Project. Open source software has been translated into Low German; this used to be coordinated via a page on Sourceforge,[32] but as of 2015, the most active project is that of KDE.[33]

Netherlands

In the early 20th century, scholars in the Netherlands argued that speaking dialects hindered language acquisition, and it was therefore strongly discouraged. As education improved, and mass communication became more widespread, the Low Saxon dialects further declined, although decline has been greater in urban centres of the Low Saxon regions. When in 1975 dialect folk and rock bands such as Normaal and Boh Foi Toch became successful with their overt disapproval of what they experienced as "misplaced Dutch snobbery" and the Western Dutch contempt for (speakers of) Low Saxon dialects, they gained a following among the more rurally oriented inhabitants, launching Low Saxon as a sub-culture. They inspired contemporary dialect artists and rock bands, such as Daniël Lohues, Mooi Wark, Jovink en de Voederbietels, Hádiejan Nonetheless, the position of the language is vulnerable according to UNESCO.[12] Between 1995 and 2011 the numbers of speakers of parents dropped from 34% in 1995 to 15% in 2011. Numbers of speakers of their children dropped in the same period from 8% to 2%.[13] Low Saxon is still spoken more widely than in Northern Germany. A 2005 study showed that in the Tweante region 62% of the inhabitants used Low Saxon daily, and up to 75% regularly. Efforts are made in Germany and in the Netherlands to protect Low German as a regional language.

Sound change

As with the Anglo-Frisian languages and the North Germanic languages, Low German has not been influenced by the High German consonant shift except for old /ð/ having shifted to /d/. Therefore, a lot of Low German words sound similar to their English counterparts. One feature that does distinguish Low German from English generally is final devoicing of obstruents, as exemplified by the words 'good' and 'wind' below. This is a characteristic of Dutch and German as well and involves positional neutralization of voicing contrast in the coda position for obstruents (i.e. t = d at the end of a syllable.) This is not used in English except in the Yorkshire dialect, where there is a process known as Yorkshire assimilation.[34]

For instance: water [wɒtɜ, ˈwatɜ, ˈwætɜ], later [ˈlɒːtɜ, ˈlaːtɜ, ˈlæːtɜ], bit [bɪt], dish [dis, diʃ], ship [ʃɪp, skɪp, sxɪp], pull [pʊl], good [ɡou̯t, ɣɑu̯t, ɣuːt], clock [klɔk], sail [sɑi̯l], he [hɛi̯, hɑi̯, hi(j)], storm [stoːrm], wind [vɪˑnt], grass [ɡras, ɣras], hold [hoˑʊl(t)], old [oˑʊl(t)].

The table below shows the relationship between Low German consonants which were unaffected by this chain shift and their equivalents in other West Germanic languages. Contemporary Swedish and Icelandic shown for comparison; Eastern and Western North Germanic languages, respectively.

| Proto-Germanic | High German | Low German | Dutch | English | German | West Frisian | Swedish | Icelandic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -k- | -ch- | maken | maken | make | machen | meitsje | maka (arch.) | maka |

| k- | k- | Keerl (fellow) | kerel | churl | Kerl * | tsjirl (arch.) | karl | karl |

| d- | t- | Dag | dag | day | Tag | dei | dag | dag |

| -t- | -ss- | eten | eten | eat | essen | ite | äta | éta |

| t- | z- (/t͡s/) | teihn | tien | ten | zehn | tsien | tio | tíu |

| -tt- | -tz-, -z- (/t͡s/) | sitten | zitten | sit | sitzen | sitte | sitta | sitja |

| -p | -f, -ff | Schipp, Schepp | schip | ship | Schiff | skip | skepp *** | skip |

| p- | pf- | Peper | peper | pepper | Pfeffer | piper | peppar | pipar |

| -β- | -b- | Wief, Wiever | wijf, wijven ** | wife, wives | Weib, Weiber ** | wiif, wiven | viv ** | víf |

Notes:

- * German Kerl is a loanword from Low German

- ** The series Wief–wijf, etc. are cognates, not semantic equivalents. The meanings of some of these words have shifted over time. For example, the correct equivalent term for "wife" in modern Dutch, German and Swedish is vrouw, Frau and fru respectively; using wijf, Weib or viv for a human is considered archaic in Swedish and nowadays derogatory in Dutch and German, comparable to "wicked girl". No cognate to Frau / vrouw / fru has survived in English (compare Old English frōwe "lady"; the English word frow "woman, lady" rather being a borrowing of the Middle Dutch word).

- *** Pronounced shepp since the 17th century

Grammar

Generally speaking, Low German grammar shows similarities with the grammars of Dutch, Frisian, English, and Scots, but the dialects of Northern Germany share some features (especially lexical and syntactic features) with German dialects.

Nouns

Low German declension has only two morphologically marked noun cases, where accusative and dative together constitute an oblique case, and the genitive case has been lost.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative | en Boom, de Boom | Bööm, de Bööm | nö Bloom, de Bloom | Blomen, de Blomen | en Land, dat Land | Lannen, de Lannen |

| Oblique | en Boom, den Boom | Bööm, de Bööm | nö Bloom, de Bloom | Blomen, de Blomen | en Land, dat Land | Lannen, de Lannen |

Dative den/dän

In most modern dialects, the nominative and oblique cases are primarily distinguished only in the singular of masculine nouns. In some Low German dialects, the genitive case is distinguished as well (e.g. varieties of Mennonite Low German.) It is marked in the masculine gender by changing the masculine definite determiner 'de' from de to den/dän. By contrast, German distinguishes four cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative. So, for example, the definite article of the masculine singular has the forms: der (nom), den (acc), des (gen), and dem (dat.) Thus case marking in Low German is simpler than in German.

Verbs

In Low German verbs are conjugated for person, number, and tense. Verb conjugation for person is only differentiated in the singular. There are five tenses in Low German: present tense, preterite, perfect, and pluperfect, and in Mennonite Low German the present perfect which signifies a remaining effect from a past finished action. For example, "Ekj sie jekomen", "I am come", means that the speaker came and he is still at the place to which he came as a result of his completed action.

| Present | Preterite | Perfect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st Person | ik slaap | wi slaapt/slapen | ik sleep | wi slepen | ik heff slapen | wi hebbt/hebben slapen |

| 2nd Person | du slöppst | ji slaapt/slapen | du sleepst | ji slepen | du hest slapen | ji hebbt/hebben slapen |

| 3rd Person | he, se, dat slöppt | se slaapt/slapen | he, se, dat sleep | se slepen | he, se, dat hett slapen | se hebbt/hebben slapen |

Unlike Dutch, German, and southern Low German, the northern dialects form the participle without the prefix ge-, like the Scandinavian languages, Frisian and English. Compare to the German past participle geschlafen. This past participle is formed with the auxiliary verbs hebben "to have" and wesen/sien "to be". It should be noted that e- is used instead of ge- in most Southern (below Groningen in the Netherlands) dialects, though often not when the past participle ends with -en or in a few oft-used words like west (been).

The reason for the two conjugations shown in the plural is regional: dialects in the central area use -t while the dialects in East Frisia and the dialects in Mecklenburg and further east use -en. The -en suffix is of Dutch influence. The -t ending is however more often encountered, even in areas where -en endings were prominent due to the fact that these -t endings are seen as kennzeichnend Niederdeutsch, that is to say a well-known feature of Low German.

There are 26 verb affixes.

There is also a progressive form of verbs in present, corresponding to the same in the Dutch language. It is formed with wesen (to be), the preposition an (at) and "dat" (the/it).

| Low German | Dutch | English | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main form | Ik bün an't Maken. | Ik ben aan het maken. | I am making. |

| Main form 2 | Ik do maken.1 | - | - |

| Alternative form | Ik bün an'n Maken.2 | Ik ben aan het maken. | - |

| Alternative form 2 | Ik bün maken.3 | Ik ben makende. | I am making. |

- 1 Instead of 'to wesen, sien (to be) Saxon uses doon (to do) to make to present continuous.

- 2 Many see the 'n as an old dative ending of dat which only occurs when being shortened after prepositions. This is actually the most frequently-used form in colloquial Low German.

- 3 This form is archaic and mostly unknown to Low German speakers. It is the same pattern as in the English example "I am making." The present participle has the same form as the infinitive: maken is either "to make" or "making".

Adjectives

The forms of Low German’s adjectives are distinct from other closely related languages such as German and English. These forms fall somewhere in between these two languages. Unlike German, Low German does not have a distinction for strong and weak forms of adjectives. However, its adjectives still do have endings, whereas English adjectives do not. The adjectives in Low German make a distinction between singular and plural to agree with the nouns that it modifies.[35] To express the difference between the singular and plural, Low German uses the following adjective endings:

| Adjective Ending | Example | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| (zero) | lütt | small |

| -e (singular) | dat lütte Huus | the small house |

| -en (plural) | de lütten Hüüs | the small houses |

Personal pronouns

Like German, Low German maintains the historical Germanic distinction between the second person singular and second person plural. In English and German, this distinction would translate to “thou” and “du” referring to one person, and “ye” and “ihr” referring to more than one person. The second person pronouns for each case are given below to further illustrate this distinction.[35]

| Case | Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | du | “thou” | ji | “ye” |

| Accusative | di | “thee” | jug | “you” |

| Dative | di | “thee” | jug | “you” |

| Genitive | din, dinen | “thy”, “thine” | jug’ | “your” |

In the genitive (possessive) case, the pronoun functions in the same way as an adjective and so it may take an ending if needed to match the singular or plural status of the noun it is modifying. So, for example, if “you” possess multiple books, then [dinen] would be used to express that the singular second person possesses multiple objects: the books. If several people in the second person (“you all”) possessed multiple books, then [jug’] would be used instead.[35]

Phonology

Consonants

Since there is no standard Low German, there is no standard Low German consonant system. However, one trait present in the whole Low German speaking area,[36] is the retraction of /s z/ to [s̠ z̠].[36]

The table shows the consonant system of North Saxon, a West Low Saxon dialect.[37]

| Labial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal-Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ | x ɣ | h |

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Approximant/Trill | r | l |

Writing system

Low German is written using the Latin alphabet. There is no true standard orthography, only several locally more or less accepted orthographic guidelines, those in the Netherlands mostly based on Dutch orthography, and those in Germany mostly based on German orthography. To the latter group belongs the standard orthography devised by Johannes Sass. It is mostly used by modern official publications and internet sites, especially the Low German Wikipedia. This diversity, a result of centuries of official neglect and suppression, has a very fragmenting and thus weakening effect on the language as a whole, since it has created barriers that do not exist on the spoken level[38]. Interregional and international communication is severely hampered by this. Most of these systems aim at representing the phonetic (allophonic) output rather than underlying (phonemic) representations, but trying to conserve many etymological spellings. Furthermore, many writers follow guidelines only roughly. This adds numerous idiosyncratic and often inconsistent ways of spelling to the already existing great orthographic diversity.

In 2011, writers of the Dutch Low Saxon Wikipedia developed a spelling that would be suitable and applicable to all varieties of Low Saxon in the Netherlands, although the semi-official dialect institutes have not picked up on this, or indicated that they believed that yet another writing system will only further confuse dialect writers rather than suit them. The new spelling was introduced to the Dutch Low Saxon Wikipedia to unify the spelling of categories, templates and comparable source code writings.

In 2018, a team of writers from both the Dutch and the German Low Saxon Wikipedia completed the New Saxon Spelling, which aims to unite the different spelling systems of the Netherlands and Germany. Unlike traditional spelling systems, this spelling does not focus on correct display of pronunciation, but instead seeks mutual legibility for both German and Dutch readers of Low Saxon, based on etymology. Readers may apply their own pronunciation. As such, it can be seen as an extension of the Algemeyne Schrievwies' by Reinhard Franz Hahn.

Notable Low German writers and performers

- Heinrich Bandlow

- Eggerik Beninga

- Hans-Friedrich Blunck

- Reuben Epp

- De fofftig Penns

- Gorch Fock

- Johannes Gillhoff

- Klaus Groth

- August Hermann

- Sam Marx, father of the Marx Brothers[39].

- Fritz Reuter

- Julius Stinde

- Albert Suho

- Rudolf Tarnow

- Wilhelm Wieben

- Balthasar Russow

- Also: Wilhelm Busch would, in some of his High German rhymed stories, include excerpts in Low German.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 5 million in northern Germany and 1.7 million in eastern Netherlands

References

- 1 2 3 "Gechattet wird auf Plattdeusch". Noz.de. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- 1 2 3 The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic, and Educational Perspectives by Guus Extra, Durk Gorter; Multilingual Matters, 2001 - 454; page 10.

- ↑ Saxon, Low Ethnologue.

- ↑ German: § 23 Absatz 1 Verwaltungsverfahrensgesetz (Bund).

Die Frage, ob unter deutsch rechtlich ausschließlich die hochdeutsche oder auch die niederdeutsche Sprache subsumiert wird, wird juristisch uneinheitlich beantwortet: Während der BGH in einer Entscheidung zu Gebrauchsmustereinreichung beim Deutschen Patent- und Markenamt in plattdeutscher Sprache das Niederdeutsche einer Fremdsprache gleichstellt („Niederdeutsche (plattdeutsche) Anmeldeunterlagen sind im Sinn des § 4a Abs. 1 Satz 1 GebrMG nicht in deutscher Sprache abgefaßt.“ – BGH-Beschluss vom 19. November 2002, Az. X ZB 23/01), ist nach dem Kommentar von Foerster/Friedersen/Rohde zu § 82a des Landesverwaltungsgesetzes Schleswig-Holstein unter Verweis auf Entscheidungen höherer Gerichte zu § 184 des Gerichtsverfassungsgesetzes seit 1927 (OLG Oldenburg, 10. Oktober 1927 – K 48, HRR 1928, 392) unter dem Begriff deutsche Sprache sowohl Hochdeutsch wie auch Niederdeutsch zu verstehen. - ↑ Unterschiedliche Rechtsauffassungen, ob Niederdeutsch in Deutschland insgesamt Amtssprache ist – siehe dazu: Amtssprache (Deutschland); zumindest aber in Schleswig-Holstein und Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

- ↑ Maas, Sabine (2014). Twents op sterven na dood? : een sociolinguïstisch onderzoek naar dialectgebruik in Borne. Münster New York: Waxmann. p. 19. ISBN 3830980337.

- ↑ Cascante, Manuel M. (8 August 2012). "Los menonitas dejan México". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 February 2013.

Los cien mil miembros de esta comunidad anabaptista, establecida en Chihuahua desde 1922, se plantean emigrar a la república rusa de Tartaristán, que se ofrece a acogerlos

- ↑ Los Menonitas en Bolivia Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. CNN en Español

- ↑ El Comercio: Menonitas cumplen 85 años en Paraguay con prosperidad sin precedentes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Low German". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Bloemhoff, H. (2005). Taaltelling Nedersaksisch. Een enquête naar het gebruik en de beheersing van het Nedersaksisch in Nederland. Groningen: Sasland.

- 1 2 "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". www.unesco.org.

- 1 2 Driessen, Geert (2012). "Ontwikkelingen in het gebruik van Fries, streektalen en dialecten in de periode 1995-2011" (PDF). Radboud University Nijmegen. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ "Platdietsch". 2008-01-27. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ↑ "O trilinguismo no Colégio Fritz Kliewer de Witmarsum. (Paraná) [The trilingualism the College of Fritz Kliewer Witmarsum (Paraná)]" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Elvine Siemens Dück. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) Claudio Vereza, Espírito Santo's state assemblyman by the Workers' Party | The Pomeranian people in Espírito Santo Archived 21 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ethnologue 19th Edition (2016)

- ↑ U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration - Language Use in the United States: 2007

- ↑ Cf. the definition of high in the Oxford English Dictionary (Concise Edition): "[…] situated far above ground, sea level, etc; upper, inland, as […] High German".

- ↑ "Mundart/Platt". www.philhist.uni-augsburg.de. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ J. Goossens: "Niederdeutsche Sprache. Versuch einer Definition", in: J. Goossens (ed.), Niederdeutsch. Sprache und Literatur, vol. 1, Neumünster 1973.

- ↑ W. Sanders: Sachsensprache — Hansesprache — Plattdeutsch. Sprachgeschichtliche Grundzüge des Niederdeutschen, Göttingen 1982, p. 32, paraphrasing Heinz Kloss: "Abstandsprachen und Ausbausprachen", in: J. Göschel et al. (edd.), Zur Theorie des Dialekts, Wiesbaden 1976, pp. 301–322.

- ↑ Hubertus Menke: "Niederdeutsch: Eigenständige Sprache oder Varietät einer Sprache?", in: Eva Schmitsdorf et al. (edd.), Lingua Germanica. Studien zur deutschen Philologie. Jochen Splett zum 60. Geburtstag, Waxmann, Münster et al. 1998, pp. 171–184, in particular p. 180.

- ↑ Hubertus Menke: "Niederdeutsch: Eigenständige Sprache oder Varietät einer Sprache?", in: Eva Schmitsdorf et al. (edd.), Lingua Germanica. Studien zur deutschen Philologie. Jochen Splett zum 60. Geburtstag, Waxmann, Münster et al. 1998, pp. 171–184, in particular p. 183f.

- ↑ Cf. Institut für niederdeutsche Sprache – Sprachenpolitik

- ↑ Sprachenchartabericht of the regional government of Schleswig-Holstein for 2016, p. 14 f.

- ↑ Cf. the German Wikipedia article on Niederdeutsche Sprache.

- ↑ Sanders, W. (1982) Sachsensprache, Hansesprache, Plattdeutsch. Sprachgeschichtliche Grundzüge des Niederdeutschen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht.

- 1 2 3 Langer, Nils and Robert Langhanke. "How to Deal with Non-Dominant Languages – Metalingusitic Discourses on Low German in the Nineteenth Century". Linguistik Online. 58.1.

- ↑ "Low Saxon". Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ↑ http://l10n.kde.org/stats/gui/trunk-kde4/nds/

- ↑ "Linux op Platt". 1 July 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Hartlich willkamen bi KDE op Platt". nds.i18n.kde.org. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ See John Wells, Accents of English, pages 366-7, Cambridge University Press, 1981

- 1 2 3 Biddulph, Joseph (2003). Platt and Old Saxon: Plattdeutsch (Low German) in its Modern and Historical Forms. Wales: Cyhoeddwr JOSEPH BIDDULPH Publisher.

- 1 2 Adams (1975:289)

- ↑ R.E. Keller, German Dialects. Phonology and Morphology, Manchester 1960

- ↑ Dieter Stellmacher: Niederdeutsche Grammatik - Phonologie und Morphologie. In: Gerhard Cordes & Dieter Möhn: Handbuch zur niederdeutschen Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag 1983, p.239.

- ↑ Marx, Harpo; Barber, Rowland (1961). Harpo Speaks.

Bibliography

- Adams, Douglas Q. (1975), "The Distribution of Retracted Sibilants in Medieval Europe", Language, Linguistic Society of America, 51 (2): 282–292, doi:10.2307/412855, JSTOR 412855

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Low German language. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Low German phrasebook. |

| Low German (Germany) edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Low Saxon (Netherlands) edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Plautdietsch test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Plattdeutsch. |

- http://www.plattmaster.de/

- http://www.platt-online.de/

- http://www.zfn-ratzeburg.de/

- http://www.deutsch-plattdeutsch.de/

Online dictionaries

- Plattmakers dictionary with more than 10,000 word entries, with translations and interface available in several languages (English too)

- Dictionary of the Drents dialect (Dutch)

- Mennonite Low German-English Dictionary

- List of more than 100 published dictionaries

Information

- Low German Podcasts, Audio and Videos (Oolland dialect)

- Streektaal.net, information in and about various Low German dialects

- Nu is de Welt platt! International resources in and about Low German

- Niederdeutsch/Plattdeutsch in Westfalen, by Olaf Bordasch

- Mönsterlänner Plat, by Klaus-Werner Kahl

- Plattdeutsch heute

- Building Blocks of Low Saxon (Low German), an introductory grammar in English and German

Organizations

- TwentseWwelle (Twente, the Netherlands)

- IJsselacademie (Overijssel and Veluwe, the Netherlands)

- Staring Instituut (Achterhoek, the Netherlands)

- Oostfreeske Taal (Eastern Friesland, Germany)

- Drentse Taol (Drenthe, the Netherlands)

- Stichting Stellingwarver Schrieversronte (Friesland, the Netherlands)

- SONT (General, the Netherlands)

- Institut für niederdeutsche Sprache e.V. (General, Germany)

- Diesel - dat oostfreeske Bladdje (Eastern Friesland, Germany)