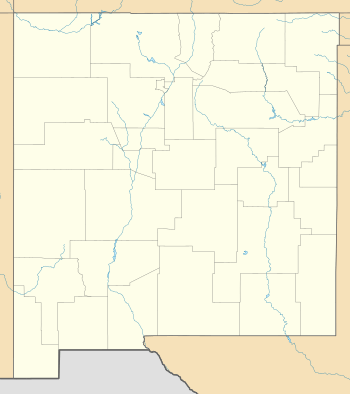

Mount Taylor (New Mexico)

Mount Taylor (Navajo: Tsoodził) is a dormant stratovolcano in northwest New Mexico, northeast of the town of Grants.[3] It is the high point of the San Mateo Mountains[lower-alpha 1] and the highest point in the Cibola National Forest. It was named in 1849 for then president Zachary Taylor. Prior to that, it was called Cebolleta (tender onion) by the Spanish; the name persists as one name for the northern portion of the San Mateo Mountains, a large mesa. Mount Taylor is largely forested with some meadows, rising above the desert below. The ancient caldera is heavily eroded to the east. Its slopes were an important source of lumber for neighboring pueblos.

| Mount Taylor | |

|---|---|

| Tsoodził (in Navajo) | |

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 11,305 ft (3,446 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 4,094 ft (1,248 m) [2] |

| Coordinates | 35°14′19″N 107°36′31″W [1] |

| Geography | |

Mount Taylor | |

| Location | Cibola County, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Parent range | San Mateo Mountains |

| Topo map | USGS Mount Taylor |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike |

Mount Taylor is the cone in a larger volcanic field, including Mesa Chivato. The Mount Taylor volcanic field is composed primarily of basalt (with 80% by volume) and straddles the extensional transition zone between the Colorado Plateau and the Rio Grande rift.[4] The largest volcanic plug in the volcanic field is Cabezon Peak, which rises nearly 2,000 feet above the surrounding plain.

According to Robert Julyan's The Place Names of New Mexico, the Navajos identify Cabezon Peak "as the head of a giant killed by the Twin War Gods" with the lava flow to the south of Grants believed to be the congealed blood of the giant.[5]

Native American traditions

To the Navajo people, Mount Taylor is Tsoodził, the blue bead mountain, sometimes translated Turquoise Mountain, one of the four sacred mountains marking the cardinal directions and the boundaries of the Dinetah, the traditional Navajo homeland. Mount Taylor marks the southern boundary, and is associated with the direction south and the color blue; it is gendered female. In Navajo mythology, First Man created the sacred mountains from soil from the Fourth World, together with sacred matter, as replicas of mountains from that world. He fastened Mount Taylor to the earth with a stone knife. The supernatural beings Black God, Turquoise Boy, and Turquoise Girl are said to reside on the mountain.[6] Mount Taylor is also sacred to the Acoma, Hopi, Laguna and Zuni people.

Volcanology

Mount Taylor was active from 3.3 to 1.5 million years ago[7] during the Pliocene, and is surrounded by a field of smaller inactive volcanoes. Repeated eruptions built lava domes and produced lava flows, ash plumes, and mudflows. The mountain is surrounded by a great volume of volcanic debris, suggesting multiple major eruptions, possibly similar to that of Mount Saint Helens and the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, Arizona.[8] Estimates vary about how high the mountain was at its highest. Conservative estimates place its maximum near a similar pre-explosion height for the San Francisco Peaks of 16,000 to 18,000 feet (4,900 to 5,500 m), and an extreme estimate places it near 25,000 feet (7,600 m).

Recreation

Mount Taylor is the site of the Mount Taylor Winter Quadrathlon, an endurance event which has been held at this location for over thirty years, with the 2019 event being the 36th. The event includes bicycling, running, cross-country skiing and snowshoeing for 43 miles from the town of Grants to the summit and back. Since 2012 there has also been a 50-kilometer running race on Mount Taylor, sponsored by the Albuquerque Roadrunners club. Competitors who complete the 50 km run in the fall and the Quadrathlon in the following winter are known as 'Doublers' and earn a special award.

Wildlife

Mount Taylor and the surrounding area is home to large elk herds, mule deer, black bear, mountain lion and wild turkey. Bird species are particularly diverse in the area and include great blue heron, white-faced ibis, canvasback, common merganser, rough-legged hawk, red-tailed hawk, ferruginous hawk, sharp-shinned hawk, osprey, golden eagle, barn owl, great horned owl, and kestrel, whip-poor-will, white-throated swift, western kingbird, warbling vireo, western meadowlark, house finch, swifts, swallows, prairie falcon, gray-headed junco, Steller's jay, and pinyon jay. Furthermore, the area offers excellent raptor-nesting habitat on the various cliffs that spill down into the Rio Puerco valley below.

.jpg) Great blue heron are found on Mt. Taylor.

Great blue heron are found on Mt. Taylor. A mule deer fawn in the snow.

A mule deer fawn in the snow.- A mountain lion in a tree on Mount Taylor.

Mount Taylor is home to healthy populations of elk.

Mount Taylor is home to healthy populations of elk. A black bear in a tree on Mount Taylor.

A black bear in a tree on Mount Taylor.

Mining

Mount Taylor is very rich in a uranium-vanadium bearing mineral, and was mined extensively for it from 1979 to 1990. The Mount Taylor and the hundreds of other uranium mines on Pueblo lands have provided over thirteen million tons of uranium ore to the United States since 1945.

Concern has arisen regarding the impact of future mining activities on the site. In June 2008 the New Mexico Cultural Properties Review Committee voted in favor of a one-year emergency listing of more than 422,000 acres (171,000 ha) surrounding the mountain's summit on the state Register of Cultural Properties. "The Navajo Nation, the Acoma, Laguna and Zuni pueblos, and the Hopi tribe of Arizona asked the state to approve the listing for a mountain they consider sacred to protect it from an anticipated uranium mining boom, according to the nomination report."[9] In April 2009, Mount Taylor was added to the National Trust for Historic Preservation's list of America's Most Endangered Places.

Notable events

On 3 September 1929, the Transcontinental Air Transport Ford 5-AT-B Tri-Motor City of San Francisco struck Mount Taylor during a thunderstorm while on a scheduled passenger flight from Albuquerque Airport in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to Los Angeles, California, killing all eight people on board.[10]

See also

Notes

- There are two small ranges in New Mexico called the San Mateo Mountains; this is the northern one. The other range is near the Plains of San Agustin.

References

- "Taylor". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- "Mount Taylor, New Mexico". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen (1993). Volcanoes of North America. Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 0-521-43811-X.

- Kelley, Shari. "Mt. Taylor Volcanic Field". New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources.

- Julyan, Robert (1996). The Place Names of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press.

- Robert S., McPherson (1992). Sacred Land, Sacred View: Navajo perceptions of the Four Corners Region. Brigham Young University. ISBN 1-56085-008-6.

- "Mount Taylor, New Mexico". Volcano World. Oregon State University. Archived from the original on 2008-12-10. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- Chronic, Halka (1987). Roadside Geology of New Mexico. Mountain Press, Missoula. p. 50. ISBN 0-87842-209-9.

- "Tribes get Mt. Taylor listed as protected". Los Angeles Times. June 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- Aviation Safety Network: Accident Description

External links

- Cibola National Forest official website

- "Mount Taylor". Skiing the Pacific Ring of Fire and Beyond. Amar Andalkar's Ski Mountaineering and Climbing Site. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- "Memories Come To Us In the Rain and the Wind". Motion Magazine. Retrieved 2008-12-01.