Trebinje

| Trebinje Требиње | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

Clockwise, from top: Panorama of Trebinje, Trebišnjica River Bridge, View on Trebinje River | ||

| ||

Location of Trebinje within Republika Srpska | ||

| Coordinates: 42°42′43″N 18°20′46″E / 42.712°N 18.346°ECoordinates: 42°42′43″N 18°20′46″E / 42.712°N 18.346°E | ||

| Country | Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Entity | Republika Srpska | |

| City status | July 2012 | |

| Settlements | 178 (2008.) | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Luka Petrović (SNSD) | |

| Area | ||

| • City | 854,5 km2 (3,299 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 275 m (902 ft) | |

| Population (2013 Census) | ||

| • City | 31,433 | |

| • Density | 36.8/km2 (95/sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 25,589 | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Area code(s) | 59 | |

| Website |

www | |

Trebinje (Serbian Cyrillic: Требиње) is a city located in Republika Srpska, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the southernmost city in Bosnia and Herzegovina situated on the banks of Trebišnjica river in the region of East Herzegovina. As of 2013, it has a population of 31,433 inhabitants. The city's old town quarter dates to the 18th-century Ottoman period, and includes the Arslanagić Bridge.

Geography

The city lies in the Trebišnjica river valley, at the foot of Leotar, in southeastern Herzegovina, some 30 km (19 mi) by road from Dubrovnik, Croatia, on the Adriatic coast. There are several mills along the river, as well as several bridges, including three in the city of Trebinje itself, as well as a historic Ottoman Arslanagic bridge nearby. The river is heavily exploited for hydro-electric energy. After it passes through the Popovo Polje area southwest of the city, the river — which always floods in the winter — naturally runs underground to the Adriatic, near Dubrovnik. Trebinje is known as "the city of the sun and platan trees", and it is said to be one of the most beautiful cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The city is economic and cultural center of the region of Eastern Herzegovina.

Climate

| Climate data for Trebinje (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.0 (64.4) |

20.0 (68) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

37.0 (98.6) |

39.5 (103.1) |

39.0 (102.2) |

35.0 (95) |

31.5 (88.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.5 (68.9) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.5 (13.1) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.0 (41) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 179.1 (7.051) |

163.5 (6.437) |

154.2 (6.071) |

152.8 (6.016) |

86.2 (3.394) |

84.3 (3.319) |

52.2 (2.055) |

87.8 (3.457) |

125.1 (4.925) |

191.0 (7.52) |

232.8 (9.165) |

220.9 (8.697) |

1,730 (68.11) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 106 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 102.6 | 114.7 | 142.2 | 154.0 | 187.5 | 193.7 | 242.8 | 233.8 | 197.8 | 172.9 | 111.3 | 100.6 | 1,954.8 |

| Source: Meteorological Institute of Bosnia and Herzegovina[1] | |||||||||||||

History

Middle Ages

De Administrando Imperio by Constantine VII (913–959) mentioned Travunija (Τερβουνια), as a "land of the Serbs". Serbian Prince Vlastimir (r. 830–51) married his daughter to Krajina, the son of Beloje, and that family became hereditary rulers of Travunija. By 1040 Stefan Vojislav's state stretched in the coastal region from Ston in the north, down to his capital, Skadar, set up along the southern banks of the Skadar Lake, with other courts set up in Trebinje, Kotor and Bar.[2]

The town commanded the road from Ragusa to Constantinople, which was traversed in 1096 by Raymond IV of Toulouse and his crusaders.[3] It belonged to the Serbian Empire until 1355. Trebinje became a part of the expanded medieval Bosnian state under Tvrtko I in 1373. There is a medieval tower in Gornje Police whose construction is often attributed to Vuk Branković. The old Tvrdoš Monastery dates back to the 15th century.

In 1482, together with the rest of Herzegovina (see: Herzog Stjepan Vukčić Kosača), the town was captured by the Ottoman Empire. The Old Town-Kastel was built by the Ottomans on the location of the medieval fortress of Ban Vir, on the western bank of the Trebišnjica River. The city walls, the Old Town square, and two mosques were built in the beginning of the 18th century by the Resulbegović family. The 16th-century Arslanagić bridge (or Perovica bridge) was originally built at the village of Arslanagić, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north of the town, by Mehmed-Paša Sokolović, and was run by Arslanagić family for centuries. The Arslanagić Bridge is one of the most attractive Ottoman-era bridges in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It has two large and two small semicircular arches.

Among noble families in the Trebinje region mentioned in Ragusan documents were Ljubibratić, Starčić, Popović, Krasomirić, Preljubović, Poznanović, Dragančić, Kobiljačić, Paštrović, Zemljić and Stanjević.[4]

Ottoman

The burning of Saint Sava's remains after the Banat Uprising provoked the Serbs in other regions to revolt against the Ottomans.[5] Grdan, the vojvoda of Nikšić, organized revolt with Serbian Patriarch Jovan Kantul. From 1596, the center of anti-Ottoman activity in Herzegovina was the Tvrdoš Monastery in Trebinje, where Metropolitan Visarion was seated.[6] In 1596, the uprising broke out in Bjelopavlići, then spread to Drobnjaci, Nikšić, Piva and Gacko (see Serb Uprising of 1596–97). The rebels were defeated at the field of Gacko. It ultimately failed due to lack of foreign support.[6]

The hajduks in Herzegovina had in March 1655 carried out one of their greatest operations, raiding Trebinje, taking many slaves and carrying with them out much loot.[7]

On 26 November 1716, Austrian general Nastić with 400 soldiers and c. 500 hajduks attacked Trebinje, but did not take it over.[8] A combined Austro-Venetian-Hajduk force of 7,000 stood before the Trebinje walls, defended by 1,000 Ottomans.[8] The Ottomans were busy near Belgrade and with hajduk attacks towards Mostar, and were thus unable to reinforce Trebinje.[8] The conquest of Trebinje and Popovo field were given up to fight in Montenegro.[8] The Venetians took over Hutovo and Popovo, where they immediately recruited militarly from the population.[8]

Notable participants in the Herzegovina Uprising (1852–62) from Trebinje include Mićo Ljubibratić.

During the Herzegovina Uprising (1875–77), the Bileća and Trebinje region was led by serdar Todor Mujičić, Gligor Milićević, Vasilj Svorcan and Sava Jakšić.

Austria-Hungary

During the period of Austro-Hungarian administration (1878–1918), several fortifications were built on the surrounding hills, and there was a garrison based in the town. The imperial administrators also modernized the town, expanding it westwards, building the present main street, as well as several squares, parks, schools, tobacco plantations, etc.

SFR Yugoslavia (1945–92)

Trebinje grew rapidly in the era of Josip Broz Tito's Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia between 1945 and 1990. It especially developed its hydroelectric potential with dams, artificial lakes, tunnels, and hydroelectric plants. This industrial development brought a large increase in the urban population of Trebinje.

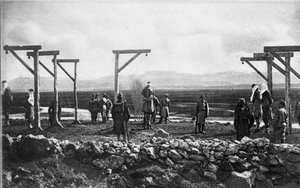

Bosnian War (1992–95)

Trebinje was the largest town in Serb-held eastern Herzegovina during the Bosnian War. It was controlled by Bosnian Serb forces from the fall of 1991, and was used as a major command and artillery base by Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) troops besieging the Croatian town of Dubrovnik. In 1992 Trebinje was declared the capital of the self-proclaimed Serbian Autonomous Region of Herzegovina (Serbian: Српска аутономна област Херцеговина). Bosniak residents were subsequently conscripted to fight with the JNA and if refused they were executed, and thus they fled the region.[9] Ten of the town's mosques were razed to the ground during the war.[10]

Settlements

Trebinje is one of two municipalities created from the former Yugoslav municipality of Trebinje of the 1991 census, the other being Ravno in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. As of 2018, it has a total of 178 settlements that comprise it (including city proper area of Trebinje):

- Aranđelovo

- Arbanaška

- Arslanagića Most

- Baonine

- Begović Kula

- Bihovo

- Bijelač

- Bijograd

- Bioci

- Bodiroge

- Bogojević Selo

- Borlovići

- Brani Do

- Brova

- Budoši

- Bugovina

- Cerovac

- Čvarići

- Desin Selo

- Diklići

- Djedići, Do

- Dobromani

- Dodanovići

- Dolovi

- Domaševo

- Donja Kočela

- Donje Čičevo

- Donje Grančarevo

- Donje Vrbno

- Donji Orovac

- Dračevo

- Dražin Do

- Drijenjani

- Dubljani

- Dubočani

- Duži

- Glavinići

- Gojšina

- Gola Glavica

- Gomiljani

- Gornja Kočela

- Gornje Čičevo

- Gornje Grančarevo

- Gornje Vrbno

- Gornji Orovac

- Grab

- Grbeši

- Grbići

- Grkavci

- Grmljani

- Hum

- Janjač

- Jasen

- Jasenica Lug

- Jazina

- Jušići

- Klikovići

- Klobuk

- Konjsko

- Korlati

- Kotezi

- Kovačina

- Kraj

- Krajkovići

- Kremeni Do

- Krnjevići

- Kučići

- Kunja Glavica

- Kutina

- Lapja

- Lastva

- Lokvice

- Lomači

- Lug

- Lušnica

- Ljekova

- Ljubovo

- Marić Međine

- Mesari

- Mionići

- Morče

- Mosko

- Mrkonjići

- Mrnjići

- Necvijeće

- Nevada

- Nikontovići

- Ograde

- Orašje Popovo

- Orašje Površ

- Orašje Zubci

- Parojska Njiva

- Petrovići

- Pijavice

- Podosoje

- Podstrašivica

- Podštirovnik

- Podvori

- Poljice Čičevo

- Poljice Popovo

- Prhinje Pridvorci

- Prosjek

- Rapti Bobani

- Rapti Zupci

- Rasovac

- Sedlari

- Skočigrm

- Staro Slano

- Strujići

- Šarani

- Šćenica Ljubomir

- Taleža

- Todorići

- Trebijovi

- Tuli

- Tulje

- Turani

- Turica

- Turmenti

- Tvrdoš

- Ubla

- Ugarci

- Ukšići

- Uskoplje

- Uvjeća

- Veličani

- Velja Gora

- Vladušići

- Vlaka

- Vlasače

- Vlaška

- Volujac

- Vrpolje Ljubomir

- Vrpolje Zagora

- Vučija

- Zagora

- Zavala

- Zgonjevo

- Žakovo

- Ždrijelovići

- Željevo

- Župa

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1948 | 27,401 | — |

| 1953 | 27,720 | +0.23% |

| 1961 | 24,176 | −1.70% |

| 1971 | 29,024 | +1.84% |

| 1981 | 30,372 | +0.46% |

| 1991 | 30,996 | +0.20% |

| 2013 | 31,433 | +0.06% |

According to the 2013 census results, the city of Trebinje has 31,433 inhabitants.

Ethnic groups

The ethnic composition of the city:

| Ethnic group | Population 1971[11] |

Population 1981[12] |

Population 1991 |

Population 2013[13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 19,362 | 18,123 | 21,349 | 29,487 |

| Bosniaks/Muslims | 4,846 | 4,405 | 5,571 | 1,005 |

| Croats | 3,350 | 2,309 | 1,246 | 315 |

| Yugoslavs | 424 | 4,154 | 1,642 | - |

| Others | 1,042 | 1,381 | 1,181 | 621 |

| Total | 29,024 | 30,372 | 30,396 | 31,433 |

Culture

The Serbian Orthodox church in Trebinje, Saborna Crkva, was built between 1888 and 1908. The Hercegovačka Gračanica monastery, a loose copy of the Gračanica monastery in Kosovo, was completed in 2000. The churches are located above the city, on the historic Crkvina Hill. The 15th-century Tvrdoš monastery is located two kilometres south-west of Trebinje, including a church which dates back to late antiquity. There is also the Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Birth of Mary in the town centre, as well as monuments dedicated to acclaimed poets Njegoš and Jovan Dučić (who was from the town). The Osman-Paša Resulbegović mosque, located in the Old Town, was originally built in 1726 and fully renovated in 2005. The Old Town walls are well preserved. The Arslanagić Bridge (1574) is located 1 km north of the town center.

Sports

The local football club, FK Leotar Trebinje, plays in the Premier League of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Transportation

In late 2009 the Government of Republika Srpska approved funding for the Trebinje airport project. The airport was intended to serve as a low cost alternative to Dubrovnik.[14] The airport was intended to be operational in 2010 and then delayed till 2011. The terminal was planned to handle 260,000 passengers annually. In January 2013 the Minister for Transport and Infrastructure for Republika Srpska, Nedeljko Cubrilovic, announced that the passenger numbers doubled in 2012 from the prior year.[15] This is despite the airport not having been built. Over 820,000 euros have been spent on the project, mostly on documentation.

Notable people

- Asmir Begović, football goalkeeper

- Beba Selimović, sevdalinka singer

- Boris Savović, basketball player

- Branislav Krunić, football player

- Dzeny, Bosnian-Swedish singer/songwriter

- Ivana Ninković, Olympic swimmer

- Nataša Ninković, Serbian actress

- Jovan Deretić, historian

- Jovan Dučić, poet and diplomat

- Nebojša Glogovac, Serbian actor

- Uroš Đerić, footballer

- Semjon Milošević, football player

- Igor Joksimović, football player

- Siniša Mulina, football player

- Srđan Aleksić, amateur actor

- Vladimir Gudelj, football player

- Arnela Odžaković, karateka

- Vladimir Radmanović, Serbian NBA player, World champion

- Sabahudin Bilalović, basketball player

- Bogić Vučković, rebel leader

- Mijat Gaćinović, Serbian football player, World U-20 and European U-19 champion

- Marko Mihojević, footballer

Gallery

Trebisnjica river in Trebinje

Trebisnjica river in Trebinje Arslanagić bridge seen from the side

Arslanagić bridge seen from the side Central street of Trebinje

Central street of Trebinje Nova Gracanica church

Nova Gracanica church Spheric view of the interior of the Nova Gracanica church

Spheric view of the interior of the Nova Gracanica church

View of Orovac, village belonging to the municipality of Trebijie

View of Orovac, village belonging to the municipality of Trebijie- Old Town

- View from the hill

References

- ↑ "Klimatski podaci za Trebinje (niz 1961 – 1990)" (in Bosnian). Meteorological Institute of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Fine 1991, p. 206.

- ↑

- ↑ Milan Vasić (1995). Bosna i Hercegovina od srednjeg veka do novijeg vremena: međunarodni naučni skup 13-15. decembar 1994. Istorijski institut SANU. p. 77.

- ↑ Bataković 1996, p. 33.

- 1 2 Ćorović, Vladimir (2001) [1997]. "Преокрет у држању Срба". Историја српског народа (in Serbian). Belgrade: Јанус.

- ↑ Mihić 1975, p. 181.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mihić 1975, p. 196.

- ↑ Human Rights Watch 1993, p. 382.

- ↑ Bose 2002, p. 156.

- ↑ "Nacionalni Sastav Stanovništva SFR Jugoslavije" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Republički zavod za statistiku (Srbija). Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ↑ "Nacionalni Sastav Stanovništva SFR Jugoslavije" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Republički zavod za statistiku (Srbija). Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ↑ "POPIS STANOVNIŠTVA, DOMAĆINSTAVA I STANOVA U BOSNI I HERCEGOVINI, 2013. REZULTATI POPISA" (PDF). popis2013.ba (in Serbian). Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ↑ "Trebinje to get airport in 2010". Limun.hr. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- ↑ "EX-YU Aviation News: "Trebinje Airport doubles passenger numbers"". Exyuaviation.blogspot.com. 2013-02-01. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

Sources

- Bose, Sumantra (2002). Bosnia After Dayton: Nationalist Partition and International Intervention. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515848-9.

- Human Rights Watch (1993). War Crimes in Bosnia-Hercegovina, Volume 2. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-097-1.

- Bataković, Dušan T. (1996). The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina: History and Politics. Dialogue Association.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trebinje. |