Terai

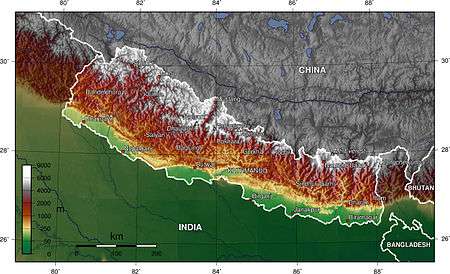

The Terai (Hindi: तराई Nepali: तराइ) is a lowland region in southern Nepal and northern India that lies south of the outer foothills of the Himalayas, the Siwalik Hills, and north of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. This lowland belt is characterised by tall grasslands, scrub savannah, sal forests and clay rich swamps. In northern India, the Terai spreads from the Yamuna River eastward across Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The Terai is part the Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands ecoregion. The corresponding lowland region in West Bengal, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Assam in the Brahmaputra River basin is called 'Dooars'.[1] In Nepal, the Terai stretches over 33,998.8 km2 (13,127.0 sq mi), about 23.1% of Nepal's land area, and lies at an altitude of between 67 and 300 m (220 and 984 ft). The region comprises more than 50 wetlands. North of the Terai rises the Bhabhar, a narrow but continuous belt of forest about 8–12 km (5.0–7.5 mi) wide.[2]

Etymology

In Hindi the region is called तराई, 'tarāī' meaning "foot-hill".[3] In Nepali, the region is called तराइ 'tarāi' meaning "the low-lying land, plain" and especially "the low-lying land at the foot of the Himālayas".[4] The region's name in Urdu is ترائي 'tarāʼī' meaning "lands lying at the foot of a watershed" or "on the banks of a river; low ground flooded with water, valley, basin, marshy ground, marsh, swamp; meadow".[5]

Geology

The Terai is crossed by the large perennial Himalayan rivers Yamuna, Ganges, Sarda, Karnali, Narayani and Kosi that have each built alluvial fans covering thousands of square kilometres below their exits from the hills. Medium rivers such as the Rapti rise in the Mahabharat Range. The geological structure of the region consists of old and new alluvium, both of which constitute alluvial deposits of mainly sand, clay, silt, gravels and coarse fragments. The new alluvium is renewed every year by fresh deposits brought down by active streams, which engage themselves in fluvial action. Old alluvium is found rather away from river courses, especially on uplands of the plain where silting is a rare phenomenon.[6]

A large number of small and usually seasonal rivers flow through the Terai, most of which originate in the Siwalik Hills. The soil in the Terai is alluvial and fine to medium textured. Forest cover in the Terai and hill areas has decreased at an annual rate of 1.3% between 1978 and 1979, and 2.3% between 1990 and 1991.[2] With deforestation and cultivation increasing, a permeable mixture of gravel, boulders and sand evolves, which leads to a sinking water table. But where layers consist of clay and fine sediments, the groundwater rises to the surface and heavy sediment is washed out, thus enabling frequent and massive floods during monsoon, such as the 2008 Bihar flood.[7]

The reduction in slope as rivers exit the hills and then transition from the sloping Bhabhar to the nearly level Terai causes current to slow and the heavy sediment load to fall out of suspension. This deposition process creates multiple channels with shallow beds, enabling massive floods as monsoon-swollen rivers overflow their low banks and shift channels. Many areas show erosion such as gullies.

Climate

| Biratnagar, 26°N, 87°E | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chandigarh, 30°N, 77°E | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are several differences between the climate on the western edge of the Terai at Chandigarh in India and at Biratnagar in Nepal near the eastern edge.

- Moving inland and away from monsoon sources in the Bay of Bengal, the climate becomes more continental with a greater difference between summer and winter.

- In the far western Terai, which is five degrees latitude further north, the coldest months' average is 3 °C (37 °F) cooler.

- Total rainfall markedly diminishes from east to west. The monsoon arrives later, is much less intense and ends sooner. However, winters are wetter in the west.

Geography

In India, the Terai extends over the states of Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal. These are mostly the districts of these states that are on the Indo-Nepal border:[1]

- Haryana: Panchkula district

- Uttarakhand: Haridwar district,[8] Udham Singh Nagar and Nainital districts[9]

- Uttar Pradesh: Pilibhit district, Lakhimpur Kheri district, Bahraich district, Shravasti district, Balrampur district, Siddharthnagar district, Maharajganj district[10]

- Bihar: West Champaran district, East Champaran district, Sitamarhi district, Madhubani district, Supaul district, Araria district, Kishanganj district

- West Bengal: Siliguri subdivision of Darjeeling district[11]

The Terai in Nepal is differentiated into "Inner" and "Outer" Terai and includes 20 districts.

Inner Terai

The Inner Terai consists of five elongated valleys located between the Mahabharat and Shivalik ranges.[12] From north-west to south-east these valleys are:

- Surkhet Valley (Nepali: सुर्खेत) in the Surkhet district, north of the Kailali and Bardiya districts;[13]

- Dang Valley (Nepali: दाङ) in the Dang Deokhuri district;[13]

- Deukhuri Valley (Nepali: देउखुरी) located south of the Dang Valley;[13]

- Chitwan Valley (Nepali: चितवन) stretching across the Chitwan and Makwanpur districts;[13]

- Kamala Valley, also called Udayapur Valley (Nepali: उदयपुर), in the Udayapur district north of the Siraha and Saptari districts.[13][14]

Most of these valleys are 5–10 km (3.1–6.2 mi) wide (north-south) and up to 100 km (62 mi) long (east-west).

Outer Terai

The Outer Terai begins south of the Siwalik Hills and extends to the Indo-Gangetic plain. In the Far-Western Region, Nepal it comprises the Kanchanpur and Kailali districts, and in the Mid-Western Region, Nepal Bardiya and Banke districts. Farther east, the Outer Terai comprises the Kapilvastu, Rupandehi, Nawalparasi, Parsa, Bara, Rautahat, Sarlahi, Mahottari, Dhanusa, Siraha, Saptari, Sunsari, Morang and Jhapa districts.[13]

East of Banke the Nepalese Outer Terai is interrupted where the international border swings north and follows the edge of the Siwaliks adjacent to Deukhuri Valley. Here the Outer Terai is entirely in Uttar Pradesh's Shravasti and Balrampur districts. East of Deukhuri the international border extends south again and Nepal has three more Outer Terai districts.

Protected areas

Several protected areas were established in the Terai since the late 1950s:

- Sonaripur Wildlife Sanctuary, now Dudhwa National Park in 1958[15]

- Kishanpur Wildlife Sanctuary in 1972[16]

- Chitwan National Park in 1973[2]

- Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary in 1975[15]

- Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve in 1976[2]

- Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve in 1976[2]

- Udaypur Wildlife Sanctuary in 1978[17]

- Rajaji National Park in 1983[16]

- Parsa National Park in 1984[2]

- Bardia National Park in 1988[2]

- Valmiki National Park in 1989[18]

- Jhilmil Jheel Conservation Reserve in 2005[8]

- Banke National Park in 2010[19]

Ethnic groups

Tharu and Dhimal people are the indigenous inhabitants of the Terai forests.[20] Several Tharu subgroups are scattered over most of the Nepal and Indian Terai.[10][21][22] They used to be semi-nomadic, practised shifting cultivation and collected wild fruits, vegetables and medicinal herbs.[23] They have been living in the Terai for many centuries and reputedly had an innate resistance to malaria.[24] Dhimal reside in the eastern Nepal Terai, viz Sunsari, Morang and Jhapa districts. In the past, they lived in the fringes of the forest and conducted a semi-nomadic life to evade outbreaks of diseases. Today, they are subsistence farmers.[20]

The Bhoksa people are indigenous to the western Terai in the Indian Kumaon division.[9]

Maithils inhabit the Indian Terai in Bihar and the eastern Terai in Nepal. Bhojpuris reside in the central and eastern Terai, and Awadhis live in the central and western Terai. Bantawa people reside foremost in two districts of the eastern Terai in Nepal.[25]

Following the malaria eradication program using DDT in the 1960s, a large and heterogeneous non-Tharu population settled in the Nepal Terai.[24] Pahari people from the mid-hills including Bahun, Chhetri and Newar moved to the plains in search of arable land. In the rural parts of the Nepal Terai, distribution and value of land determine economic hierarchy to a large extent. High caste migrants from the hills and traditional Tharu landlords who own agriculturally productive land constitute the upper level of the economic hierarchy. The poor are the landless or near landless Terai Dalits, including the Musahar, Chamar and Mallah.[26] Several Chepang people also live in Nepal's central and eastern Terai districts.[27][28]

As of June 2011, the human population in the Nepal Terai totalled 13,318,705 people in 2,527,558 households comprising more than 120 different ethnic groups and castes such as Badi, Chamling, Ghale, Kumal, Limbu, Magar, Muslim, Rajbanshi, Teli, Thakuri, Yadav and Majhi speaking people.[29]

History

.jpg)

The Muslim invasion of northern India during the 14th century caused Hindu and Buddhist people to seek refuge from religious persecution. Rajput nobles and their entourage migrated to the Himalayan foothills and gained control over the region from Kashmir to the eastern Terai during the next three centuries.[30]

Until the mid 18th century, the Nepal Terai was divided into several smaller kingdoms, and the forests were little disturbed.[31] The Kingdom of Chaudandi ruled by scion of Palpa Kingdom controlled the Terai districts of Saptari, Siraha, Dhanusa, Mahottari and Sarlahi.[32] The Makwanpur Kingdom controlled the central Terai region of present-day Nepal.[32] The Bijayapur Kingdom ruled Sunsari, Morang and Jhapa districts.[33] The Tulsipur State in the Dang Valley of Nepal's western Terai was also an independent kingdom, until it was conquered in 1785 by Bahadur Shah of Nepal during the unification of Nepal.[34] The Shah rulers also conquered land in the eastern Terai that belonged to the Kingdom of Sikkim.[35] Since the late 18th century, they encouraged Indian people to settle in the Terai and supported famine-stricken Bihari farmers to convert and cultivate land in the eastern Nepal Terai.[36] From at least 1786 onwards, the Shah rulers appointed government officers in the eastern Terai districts of Parsa, Bara, Rautahat, Mahottari, Saptari and Morang to levy taxes, collect revenues, and capture elephants and rhinos.[37][38]

The far-western and mid-western regions of the Nepal Terai called 'Naya Muluk' (new country) lay on the northern periphery of the Awadh dynasty. After Nepal lost the Anglo–Nepalese War in 1816, the British annexed these regions in the Terai when the Sugauli Treaty was ratified. But as reward for Nepal's military aid in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, they returned some of this region in 1860, namely today's districts Kanchanpur, Kailali, Banke and Bardiya.[13]

Dacoit gangs retreated to the Terai jungles, and the area was considered lawless and primitive by the British, who sought control of the region's valuable timber reserves.[39]

Indian immigration increased between 1846 and 1950.[36] Immigrants settled in the eastern Nepal Terai together with native Terai peoples.[13] The Indian Terai remained largely uninhabited until the end of the 19th century, as it was arduous and dangerous to penetrate the dense and marshy malarial jungle.[40] The region was densely forested with stands of foremost Sal.[13]

Heavy logging began in the 1920s. Extracted timber was exported to India to collect revenues. Cleared areas were subsequently used for agriculture.[31] But still, the Terai jungles were teaming with wildlife.[41]

Inner Terai valleys historically were agriculturally productive but extremely malarial. Some parts were left forested by official decree during the Rana dynasty as a defensive perimeter called Char Kose Jhadi, meaning 'four kos forest'; one kos equals about 3 km (1.9 mi). A British observer noted, "Plainsmen and paharis generally die if they sleep in the Terai before November 1 or after June 1." British travelers to Kathmandu went as fast as possible from the border at Raxaul to reach the hills before nightfall.[13]

Malaria was eradicated using DDT in the mid-1950s. Subsequently, people from the hills migrated to the Terai.[42] About 16,000 Tibetan refugees settled in the Nepal Terai in 1959–1960, followed by refugees of Nepali origin from Burma in 1964, from Nagaland and Mizoram in the late 1960s, and about 10,000 Bihari Muslims from Bangladesh in the 1970s.[43] Timber export continued until 1969. In 1970, the king granted land to loyal ex-army personnel in the districts of Jhapa, Sunsari, Rupandehi and Banke, where seven colonies were developed for resettling about 7,000 people. They acquired property rights over uncultivated forest and 'waste' land, thus accelerating the deforestation process in the Terai.[42] Between 1961 and 1991, the annual population growth in the Terai was higher than the national average, which indicates that migration from abroad occurred at a large scale. Deforestation continued, and forest products from state-owned forest were partly smuggled to India. Community forestry was introduced in 1995.[44] Since the 1990s, migration from the Terai to urban centres is increasing and causing sociocultural changes in the region.[45]

Politics

The Janatantrik Terai Mukti Morcha is a separatist organisation founded in 2004 by Jay Krishna Goit with the aim of gaining independence for the Terai (Madhesh) region from Nepal.[46] Organisation members have been responsible for various acts of terrorism including bombings and murders.[47] Other armed outfits have appeared that also demand secession through violent means including the "Terai Army", "Madhesh Mukti Tigers" and the "Tharuwan National Liberation Front". There is also movement that is demanding the secession of the region from Republic of Nepal led by CK Raut called the Alliance for Independent Madhesh, a group of activists, parties and organisations.[48][49]

Border disputes

The most significant border dispute of the Indo-Nepal boundary in the Terai region is the Susta area.[50][51] In the Susta region, 14,500 hectares of land is generally dominated by Indian side with support of Seema Shashatra Bal (SSB) forces.[50]

Indian influence in Nepal Terai

After the Nepalese Constituent Assembly election, 2008, Indian politicians kept on trying to secure strategic interests in the Nepal Terai, such as over hydropower energy, development projects, business and trade.[52] The government of Nepal has accused India of imposing an undeclared blockade in 2015.[53] India has denied the allegations, stating the supply shortages have been imposed by Madheshi protesters within Nepal, and that India has no role in it.[54]

Humanitarian works

Dhurmus Suntali Foundation handed over an integrated community containing 50 houses to Musahar community of Bardibas at a cost of Rs. 63 million.[55]

Economy

Economy in Indian Terai

Tea cultivation was introduced in the Darjeeling Terai in 1862.[11]

Economy in Nepal Terai

The Terai is the most productive region in Nepal with the majority of the country's industries. Agriculture is the basis of the economy.[56] Major crops include rice, wheat, pulses, sugarcane, jute, tobacco, and maize. In the eastern districts from Parsa to Jhapa agro-based industries are supported including: jute factories, sugar mills, rice mills and tobacco factories. The Terai is also known for beekeeping and honey production, with about 120,000 colonies of Apis cerana.[57]

In the Jhapa district, tea has been cultivated since 1960; the annual production of 2005 was estimated at 10.1 million kg.[58]

Cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants in Nepal's Terai include:

| Municipality | District | Census 2001 | Economy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biratnagar | Morang | 166,674 | agro-industry, education, trade and transport hub |

| Birganj | Parsa | 112,484 | trade and transport hub, agro- and other industries |

| Dharan | Sunsari | 95,332 | tourism hub and destination, education, financial services |

| Bharatpur | Chitwan | 89,323 | agro-industry and food processing, tourism, health care, education |

| Bhim Dutta | Kanchanpur | 80,839 | transport hub, education, health services |

| Butwal | Rupandehi | 75,384 | transport hub, retailing, agro-industry, health care, education |

| Hetauda | Makwanpur | 68,482 | transport hub, cement factory, large and small-scale industries |

| Dhangadhi | Kailali | 67,447 | |

| Janakpur | Dhanusa | 67,192 | transport hub, agro-industry, education, health care, pilgrimage site |

| Nepalganj | Banke | 57,535 | transport hub, retailing, financial services, health services |

| Triyuga | Udayapur | 55,291 | tourism |

| Siddharthanagar | Rupandehi | 52,569 | trade and transport hub, retailing, tourist and pilgrim services |

Transport

The Mahendra Highway crosses the Nepal Terai from Kankarbhitta on the eastern border in Jhapa District, Mechi Zone to Mahendranagar near the western border in Kanchanpur District, Mahakali Zone. It is the only motor road spanning the country from east to west.

Tourism

Tourist attractions in the Terai include:

- Har Ki Pauri on the banks of the Ganges where the river enters the Terai plains

- Lumbini, birthplace of Lord Buddha (near Siddharthanagar)

- Bardia National Park (near Nepalganj)

- Chitwan National Park (near Bharatpur)

- Janakpur

References

- 1 2 Johnsingh, A.J.T., Ramesh, K., Qureshi, Q., David, A., Goyal, S.P., Rawat, G.S., Rajapandian, K., Prasad, S. (2004). Conservation status of tiger and associated species in the Terai Arc Landscape, India Archived 2011-09-29 at the Wayback Machine.. RR-04/001, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bhuju, U.R., Shakya, P.R., Basnet, T.B., Shrestha, S. (2007). Nepal Biodiversity Resource Book. Protected Areas, Ramsar Sites, and World Heritage Sites (PDF). Kathmandu: International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development; Government of Nepal, Ministry of Environment, Science and Technology; United Nations Environment Programme, Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26.

- ↑ Bahri, H. (1989). "Learners' Sanskrit-English dictionary — Siksarthi Nepal-Angrejhi sabdakosa". Rajapala, Delhi.

- ↑ Turner, R.L. (1931). "A Comparative and Etymological Dictionary of the Nepali Language". K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, London.

- ↑ Platts, J. T. (1884). "ترائي तराई tarāʼī". A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English. W. H. Allen & Co., London.

- ↑ Das, K.K.L., Das, K.N. (1981), "Alluvial morphology of the North Bihar Plain – A study in applied geomorphology", in Sharma, H. S., Perspectives in geomorphology, 4, New Delhi: Naurung Rai Concept Publishing Company, pp. 85–105

- ↑ Bhargava, A. K., Lybbert, T. J., & Spielman, D. J. (2014). The Public Benefits of Private Technology Adoption. Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s Annual Meeting, July 2014, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- 1 2 Tewari, R. and Rawat, G.S. (2013). "Studies on the food and feeding habits of Swamp Deer (Rucervus duvaucelii duvaucelii) in Jhilmil Jheel Conservation Reserve, Haridwar, Uttarakhand, India". ISRN Zoology. 2013 (ID 278213): 1–6. doi:10.1155/2013/278213.

- 1 2 Ranjan, G. (2010). "Industrialization in the Terai and its Impact on the Bhoksas". In Sharma, K.; Mehta, S.; Sinha, A.K. Global Warming, Human Factors and Environment: Anthropological Perspectives (PDF). New Delhi: Excel India Publishers. pp. 285–292.

- 1 2 Kumar, A., Pandey, V.C. and Tewari, D.D. (2012). "Documentation and determination of consensus about phytotherapeutic veterinary practices among the Tharu tribal community of Uttar Pradesh, India" (PDF). Tropical Animal Health and Production 44 (4): 863–872.

- 1 2 Ghosh, C., Sharma, B.D. and Das, A.P. (2004). "Weed Flora of Tea Gardens of Darjeeling Terai". Nelumbo 46 (1–4): 151–161.

- ↑ Nagendra, H. (2002). Tenure and forest conditions: community forestry in the Nepal Terai. Environmental Conservation 29 (04): 530–539.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Guneratne, A. (2002). Many tongues, one people: the making of Tharu identity in Nepal. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- ↑ Rai, C. B. (2010). Analysis of timber production and institutional barriers: A case of community forestry in the Terai and Inner Terai regions of Nepal. PhD thesis, Lincoln University, Christchurch.

- 1 2 Mathur, P. K. and N. Midha (2008). Mapping of National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries, Dudhwa Tiger Reserve. WII – NNRMS - MoEF Project, Final Technical Report. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun.

- 1 2 Seidensticker, J., Dinerstein, E., Goyal, S.P., Gurung, B., Harihar, A., Johnsingh, A.J.T., Manandhar, A., McDougal, C.W., Pandav, B., Shrestha, M. and Smith, J.D. (2010). "Tiger range collapse and recovery at the base of the Himalayas". In D. W. Macdonald; A. J. Loveridge. Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 305–324.

- ↑ Negi, S. S. (2002). Handbook of National Parks, Sanctuaries, and Biosphere Reserves in India. New Delhi: Indus Publishing.

- ↑ Smith J.L.D., Ahern S.C., McDougal C. (1998). "Landscape analysis of tiger distribution and habitat quality in Nepal". Conservation Biology. 12 (6): 1338–1346. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1998.97068.x.

- ↑ DNPWC (2010). Banke National Park Archived 2012-02-15 at the Wayback Machine. Government of Nepal, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Department of National Parks and Soil Conservation

- 1 2 Rai, J. (2014). "Malaria, Tarai Adivasi and the Landlord State in the 19th century Nepal: A Historical-Ethnographic Analysis". Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology (7): 87–112.

- ↑ Krauskopff, G. (1995). "The Anthropology of the Tharus: An Annoted Bibliography". Kailash. 17 (3/4): 185–213.

- ↑ Sharma, J., Gairola, S., Gaur, R.D. and Painuli, R.M. (2011). "Medicinal plants used for primary healthcare by Tharu tribe of Udham Singh Nagar, Uttarakhand, India" (PDF). International Journal of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants 1 (3): 228–233.

- ↑ McLean, J. (1999). "Conservation and the impact of relocation on the Tharus of Chitwan, Nepal". Himalayan Research Bulletin. XIX (2): 38–44.

- 1 2 Terrenato, L., Shrestha, S., Dixit, K. A., Luzzatto, L., Modiano, G., Morpurgo, G., Arese, P. (1988). "Decreased malaria morbidity in the Tharu people compared to sympatric populations in Nepal". Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 82 (1): 1–11. PMID 3041928.

- ↑ Lewis, M. P. (ed.) (2009). Maithili Bhojpuri Awadhi Bantawa. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ↑ Hatlebakk, M. (2007). Economic and social structures that may explain the recent conflicts in the Terai of Nepal. Bergen: Chr. Michelsens Institute.

- ↑ Gurung, G. (1989). The Chepangs: A Study in Continuity and Change. Kathmandu: S. B. Shahi. p. 125.

- ↑ Lewis, M. P. (ed.) (2009). Chepang. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ↑ Central Bureau of Statistics (2012). National Population and Housing Census 2011 (PDF). Kathmandu: Government of Nepal.

- ↑ English, R. (1985). "Himalayan state formation and the impact of British rule in the nineteenth century". Mountain Research and Development. 5 (1): 61–78. doi:10.2307/3673223.

- 1 2 Gautam, A. P., Shivakoti, G. P., & Webb, E. L. (2004). "A review of forest policies, institutions, and changes in the resource condition in Nepal". International Forestry Review. 6 (2): 136–148. doi:10.1505/ifor.6.2.136.38397.

- 1 2 Pradhan 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Pradhan 2012, p. 4-5.

- ↑ Bouillier, V. (1993). "The Nepalese state and Gorakhnati yogis: the case of the former kingdoms of Dang Valley: 18–19th centuries". Contributions to Nepalese Studies. 20 (1): 29–52.

- ↑ Bagchi, R. (2012). Gorkhaland: Crisis of Statehood. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- 1 2 Dahal, D.R. (1983). "Economic development through indigenous means: A case of Indian migration in the Nepal Terai" (PDF). Contribution to Nepalese Studies. 11 (1): 1–20.

- ↑ Regmi, M. C. (1972). "Notes On The History Of Morang District". Regmi Research Series 4 (1): 1–4, 24–25.

- ↑ Regmi, M. C. (1988). "Chautariya Dalamardan Shah's venture; Subedar in Eastern and Western Nepal; A special Levy in the Eastern Tarai Region". Regmi Research Series 20 (1/2): 1–180.

- ↑ Sarkar, S. (2000). Issues in modern Indian history: for Sumit Sarkar. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan.

- ↑ Crooke, W. (1897). North-Western Provinces of India. London: Methuen & Co.

- ↑ Champion, F. W. (1932). The jungle in sunlight and shadow. London: Chatto & Windus.

- 1 2 Regmi, R. R. (1994). "Deforestation and Rural Society in the Nepalese Terai". Occasional Papers in Sociology and Anthropology. 4: 72–89.

- ↑ Subedi, B.P. (1991). "International migration in Nepal: Towards an analytical framework". Contribution to Nepalese Studies. 18 (1): 83–102.

- ↑ Chakraborty, R.N. (2001). "Stability and outcomes of common property institutions in forestry: evidence from the Terai region of Nepal" (PDF). Ecological Economics 36 (2): 341–353.

- ↑ Gartaula, H.N. and Niehof, A. (2013). "Migration to and from the Nepal Terai: shifting movements and motives". The South Asianist. 2 (2): 29–51.

- ↑ "Terrorist Organization Profile: Janatantrik Terai Mukti Morcha (JTMM)". National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START).

- ↑ Nepal Timeline Year 2004 satp.org

- ↑ "Nepal: Madhesis protest outside British embassy against 1816 treaty". indianexpress.com. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ "Alliance for Independent Madhesh (AIM)". madhesh.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- 1 2 Diplomat, Stephen Groves, The. "India and Nepal Tackle Border Disputes". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ Nepal aims to settle boundary dispute with India in 4 years Kathmandu Post

- ↑ Ojha, H. (2015). The India-Nepal Crisis. The Diplomat.

- ↑ "Nepal PM Wants India to Lift Undeclared Blockade". Retrieved 2016-09-12.

- ↑ sushmaswaraj_nepal_statement www.bbc.com/hindi

- ↑ "Dhurmus Suntali Foundation gifts homes to Musahar community". ekantipur.com. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ Sharma, R. P. (1974). Nepal: A Detailed Geographical Account. Kathmandu: Kathmandu: Pustak Sansar.

- ↑ Thapa, R. (2003). Himalayan Honeybees and Beekeeping in Nepal. Standing Commission of Beekeeping for Rural Development. Apimondia Journal.

- ↑ Thapa, A.N. (2005). Concept Paper on Study of Nepalese Tea Industry-Vision 2020 (PDF). Kathmandu: Nepal Tree Crop Global Development Alliance.

Bibliography

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, p. 278, ISBN 9788180698132

Further reading

- Chaudhary, D. 2011. Tarai/Madhesh of Nepal : an anthropological study. Ratna Pustak Bhandar, Kathmandu. ISBN 978-99933-878-2-4.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tarai. |