Terrorism

Terrorism is, in the broadest sense, the use of intentionally indiscriminate violence as a means to create terror among masses of people; or fear to achieve a financial, political, religious or ideological aim.[1] It is used in this regard primarily to refer to violence against peacetime targets or in war against non-combatants.[2] The terms "terrorist" and "terrorism" originated during the French Revolution of the late 18th century[3] but gained mainstream popularity during the U.S. presidency of Ronald Reagan (1981–89) after the 1983 Beirut barracks bombings[4] and again after the 2001 September 11 attacks[5][4][6] and the 2002 Bali bombings.[4]

There is no commonly accepted definition of "terrorism".[7][8] Being a charged term, with the connotation of something "morally wrong", it is often used, both by governments and non-state groups, to abuse or denounce opposing groups.[9][10][4][11][8] Broad categories of political organisations have been claimed to have been involved in terrorism to further their objectives, including right-wing and left-wing political organisations, nationalist groups, religious groups, revolutionaries and ruling governments.[12] Terrorism-related legislation has been adopted in various states, regarding "terrorism" as a crime.[13][14] There is no universal agreement as to whether or not "terrorism", in some definition, should be regarded as a war crime.[14][15]

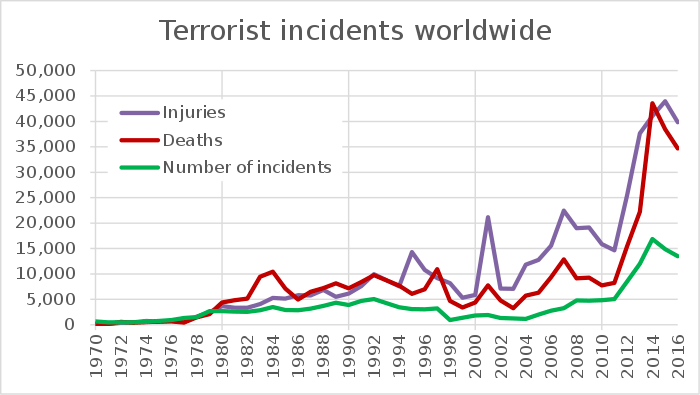

According to the Global Terrorism Database maintained by the University of Maryland, College Park, more than 61,000 incidents of non-state terrorism, resulting in at least 140,000 deaths, have been recorded from 2000 to 2014.[16]

Etymology

Etmologically, the word terror is derived from the Latin verb Tersere, which later becomes Terrere. The latter form appears in European languages as early as the 12th century; its first known use in French is the word terrible in 1160. By 1356 the word terreur is in use. Terreur is the origin of the Middle English term terrour, which later becomes the modern word "terror".[17]

Historical background

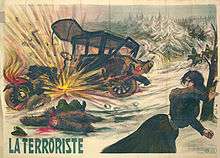

The term terroriste, meaning "terrorist", is first used in 1794 by the French philosopher François-Noël Babeuf, who denounces Maximilien Robespierre's Jacobin regime as a dictatorship.[18][19] In the years leading up to the Reign of Terror, the Brunswick Manifesto threatened Paris with an "exemplary, never to be forgotten vengeance: the city would be subjected to military punishment and total destruction" if the royal family was harmed, but this only increased the Revolution's will to abolish the monarchy.[20] Some writers attitudes about French Revolution grew less favorable after the French monarchy was abolished in 1792. During the Reign of Terror, which began in July 1793 and lasted thirteen months, Paris was governed by the Committee of Public safety who oversaw a regime of mass executions and public purges.[21]

Prior to the French Revolution, ancient philosophers wrote about tyrannicide, as tyranny was seen as the greatest political threat to Greco-Roman civilization. Medieval philosophers were similarly occupied with the concept of tyranny, though the analysis of some theologians like Thomas Aquinas drew a distinction between usurpers, who could be killed by anyone, and legitimate rulers who abused their power — the latter, in Aquinas' view, could only be punished by a public authority. John of Salisbury was the first medieval Christian scholar to defend tyrannicide.[17]

Most scholars today trace the origins of the modern tactic of terrorism to the Jewish Sicarii Zealots who attacked Romans and Jews in 1st century Palestine. They follow its development from the Persian Order of Assassins through to 19th-century anarchists. The "Reign of Terror" is usually regarded as an issue of etymology. The term terrorism has generally been used to describe violence by non-state actors rather than government violence since the 19th-century Anarchist Movement.[20][22][23]

In December 1795, Edmund Burke used the word "Terrorists" in a description of the new French government called 'Directory':[24]

At length, after a terrible struggle, the [Directory] Troops prevailed over the Citizens (…) To secure them further, they have a strong corps of irregulars, ready armed. Thousands of those Hell-hounds called Terrorists, whom they had shut up in Prison on their last Revolution, as the Satellites of Tyranny, are let loose on the people.(emphasis added)

Modern definitions

There are over 109 different definitions of terrorism.[25] American political philosopher Michael Walzer in 2002 wrote: "Terrorism is the deliberate killing of innocent people, at random, to spread fear through a whole population and force the hand of its political leaders".[8] Bruce Hoffman, an American scholar, has noted that

It is not only individual agencies within the same governmental apparatus that cannot agree on a single definition of terrorism. Experts and other long-established scholars in the field are equally incapable of reaching a consensus.[26]

C.A.J. Coady has written that the question of how to define terrorism is "irresolvable" because "its natural home is in polemical, ideological and propagandist contexts".[27]

French historian Sophie Wahnich(French) distinguishes between the revolutionary terror of the French Revolution and the terrorists of the September 11 attacks:

Revolutionary terror is not terrorism. To make a moral equivalence between the Revolution's year II and September 2001 is historical and philosophical nonsense . . . The violence exercised on 11 September 2001 aimed neither at equality nor liberty. Nor did the preventive war announced by the president of the United States.[28][29]

Experts disagree about "whether terrorism is wrong by definition or just wrong as a matter of fact; they disagree about whether terrorism should be defined in terms of its aims, or its methods, or both, or neither; they disagree about whether or not states can perpetrate terrorism; they even disagree about the importance or otherwise of terror for a definition of terrorism."[27]

State terrorism

Alternatively, responding to developments in modern warfare, Paul James and Jonathan Friedman distinguish between state terrorism against non-combatants and state terrorism against combatants, including 'Shock and Awe' tactics:

Shock and Awe" as a subcategory of "rapid dominance" is the name given to massive intervention designed to strike terror into the minds of the enemy. It is a form of state-terrorism. The concept was however developed long before the Second Gulf War by Harlan Ullman as chair of a forum of retired military personnel.[30]

United Nations

In November 2004, a Secretary-General of the United Nations report described terrorism as any act "intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to civilians or non-combatants with the purpose of intimidating a population or compelling a government or an international organization to do or abstain from doing any act".[31] The international community has been slow to formulate a universally agreed, legally binding definition of this crime. These difficulties arise from the fact that the term "terrorism" is politically and emotionally charged.[32][33] In this regard, Angus Martyn, briefing the Australian parliament, stated,

The international community has never succeeded in developing an accepted comprehensive definition of terrorism. During the 1970s and 1980s, the United Nations attempts to define the term floundered mainly due to differences of opinion between various members about the use of violence in the context of conflicts over national liberation and self-determination.[34]

These divergences have made it impossible for the United Nations to conclude a Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism that incorporates a single, all-encompassing, legally binding, criminal law definition of terrorism.[35] The international community has adopted a series of sectoral conventions that define and criminalize various types of terrorist activities.

Since 1994, the United Nations General Assembly has repeatedly condemned terrorist acts using the following political description of terrorism:

Criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the public, a group of persons or particular persons for political purposes are in any circumstance unjustifiable, whatever the considerations of a political, philosophical, ideological, racial, ethnic, religious or any other nature that may be invoked to justify them.[36]

U.S. law

Various legal systems and government agencies use different definitions of terrorism in their national legislation.

U.S. Code Title 22 Chapter 38, Section 2656f(d) defines terrorism as: "Premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents, usually intended to influence an audience".[37]

18 U.S.C. § 2331 defines "international terrorism" and "domestic terrorism" for purposes of Chapter 113B of the Code, entitled "Terrorism":

"International terrorism" means activities with the following three characteristics:

Involve violent acts or acts dangerous to human life that violate federal or state law; Appear to be intended (i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population; (ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or (iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and Occur primarily outside the territorial jurisdiction of the U.S., or transcend national boundaries in terms of the means by which they are accomplished, the persons they appear intended to intimidate or coerce, or the locale in which their perpetrators operate or seek asylum.

Media spectacle

A definition proposed by Carsten Bockstette at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, underlines the psychological and tactical aspects of terrorism:

Terrorism is defined as political violence in an asymmetrical conflict that is designed to induce terror and psychic fear (sometimes indiscriminate) through the violent victimization and destruction of noncombatant targets (sometimes iconic symbols). Such acts are meant to send a message from an illicit clandestine organization. The purpose of terrorism is to exploit the media in order to achieve maximum attainable publicity as an amplifying force multiplier in order to influence the targeted audience(s) in order to reach short- and midterm political goals and/or desired long-term end states.[38]

Terrorists also attack national symbols, which may negatively affect a government, while increasing the prestige of the given terrorist group or its ideology.[39]

Political violence

Terrorist acts frequently have a political purpose.[40] Some official, governmental definitions of terrorism use the criterion of the illegitimacy or unlawfulness of the act.[41] to distinguish between actions authorized by a government (and thus "lawful") and those of other actors, including individuals and small groups. For example, carrying out a strategic bombing on an enemy city, which is designed to affect civilian support for a cause, would not be considered terrorism if it were authorized by a government. This criterion is inherently problematic and is not universally accepted, because: it denies the existence of state terrorism.[42] An associated term is violent non-state actor.[43]

According to Ali Khan, the distinction lies ultimately in a political judgment.[44]

Pejorative use

Having the moral charge in our vocabulary of 'something morally wrong', the term 'terrorism' is often used to abuse or denounce opposite parties, either governments or non-state-groups.[9][10][4][11][8]

Those labeled "terrorists" by their opponents rarely identify themselves as such, and typically use other terms or terms specific to their situation, such as separatist, freedom fighter, liberator, revolutionary, vigilante, militant, paramilitary, guerrilla, rebel, patriot, or any similar-meaning word in other languages and cultures. Jihadi, mujaheddin, and fedayeen are similar Arabic words that have entered the English lexicon. It is common for both parties in a conflict to describe each other as terrorists.[45]

On whether particular terrorist acts, such as killing non-combatants, can be justified as the lesser evil in a particular circumstance, philosophers have expressed different views: while, according to David Rodin, utilitarian philosophers can (in theory) conceive of cases in which the evil of terrorism is outweighed by the good that could not be achieved in a less morally costly way, in practice the "harmful effects of undermining the convention of non-combatant immunity is thought to outweigh the goods that may be achieved by particular acts of terrorism".[46] Among the non-utilitarian philosophers, Michael Walzer argued that terrorism can be morally justified in only one specific case: when "a nation or community faces the extreme threat of complete destruction and the only way it can preserve itself is by intentionally targeting non-combatants, then it is morally entitled to do so".[46][47]

In his book Inside Terrorism Bruce Hoffman offered an explanation of why the term terrorism becomes distorted:

On one point, at least, everyone agrees: terrorism is a pejorative term. It is a word with intrinsically negative connotations that is generally applied to one's enemies and opponents, or to those with whom one disagrees and would otherwise prefer to ignore. 'What is called terrorism,' Brian Jenkins has written, 'thus seems to depend on one's point of view. Use of the term implies a moral judgment; and if one party can successfully attach the label terrorist to its opponent, then it has indirectly persuaded others to adopt its moral viewpoint.' Hence the decision to call someone or label some organization terrorist becomes almost unavoidably subjective, depending largely on whether one sympathizes with or opposes the person/group/cause concerned. If one identifies with the victim of the violence, for example, then the act is terrorism. If, however, one identifies with the perpetrator, the violent act is regarded in a more sympathetic, if not positive (or, at the worst, an ambivalent) light; and it is not terrorism.[48][49][50]

The pejorative connotations of the word can be summed up in the aphorism, "One man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter".[45] This is exemplified when a group using irregular military methods is an ally of a state against a mutual enemy, but later falls out with the state and starts to use those methods against its former ally. During World War II, the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army was allied with the British, but during the Malayan Emergency, members of its successor (the Malayan Races Liberation Army), were branded "terrorists" by the British.[51][52] More recently, Ronald Reagan and others in the American administration frequently called the mujaheddin "freedom fighters" during the Soviet–Afghan War[53] yet twenty years later, when a new generation of Afghan men were fighting against what they perceive to be a regime installed by foreign powers, their attacks were labelled "terrorism" by George W. Bush.[54][55][56] Groups accused of terrorism understandably prefer terms reflecting legitimate military or ideological action.[57][58][59] Leading terrorism researcher Professor Martin Rudner, director of the Canadian Centre of Intelligence and Security Studies at Ottawa's Carleton University, defines "terrorist acts" as unlawful attacks for political or other ideological goals, and said:

There is the famous statement: 'One man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter.' But that is grossly misleading. It assesses the validity of the cause when terrorism is an act. One can have a perfectly beautiful cause and yet if one commits terrorist acts, it is terrorism regardless.[60]

Some groups, when involved in a "liberation" struggle, have been called "terrorists" by the Western governments or media. Later, these same persons, as leaders of the liberated nations, are called "statesmen" by similar organizations. Two examples of this phenomenon are the Nobel Peace Prize laureates Menachem Begin and Nelson Mandela.[61][62][63][64][65][66] WikiLeaks editor Julian Assange has been called a "terrorist" by Sarah Palin and Joe Biden.[67][68]

Sometimes, states that are close allies, for reasons of history, culture and politics, can disagree over whether or not members of a certain organization are terrorists. For instance, for many years, some branches of the United States government refused to label members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) as terrorists while the IRA was using methods against one of the United States' closest allies (the United Kingdom) that the UK branded as terrorism. This was highlighted by the Quinn v. Robinson case.[69][70]

Media outlets who wish to convey impartiality may limit their usage of "terrorist" and "terrorism" because they are loosely defined, potentially controversial in nature, and subjective terms.[71][72]

History

Depending on how broadly the term is defined, the roots and practice of terrorism can be traced at least to the 1st-century AD.[73] Sicarii Zealots, though some dispute whether the group, a radical offshoot of the Zealots which was active in Judaea Province at the beginning of the 1st century AD, was in fact terrorist. According to the contemporary Jewish-Roman historian Josephus, after the Zealotry rebellion against Roman rule in Judea, when some prominent Jewish collaborators with Roman rule were killed,[74][75] Judas of Galilee formed a small and more extreme offshoot of the Zealots, the Sicarii, in 6 AD.[76] Their terror was also directed against Jewish "collaborators", including temple priests, Sadducees, Herodians, and other wealthy elites.[77]

The term "terrorism" itself was originally used to describe the actions of the Jacobin Club during the "Reign of Terror" in the French Revolution. "Terror is nothing other than justice, prompt, severe, inflexible", said Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre. In 1795, Edmund Burke denounced the Jacobins for letting "thousands of those hell-hounds called Terrorists ... loose on the people" of France.

In January 1858, Italian patriot Felice Orsini threw three bombs in an attempt to assassinate French Emperor Napoleon III.[78] Eight bystanders were killed and 142 injured.[78] The incident played a crucial role as an inspiration for the development of the early terrorist groups.[78]

Arguably the first organization to utilize modern terrorist techniques was the Irish Republican Brotherhood,[79] founded in 1858 as a revolutionary Irish nationalist group[80] that carried out attacks in England.[81] The group initiated the Fenian dynamite campaign in 1881, one of the first modern terror campaigns.[82] Instead of earlier forms of terrorism based on political assassination, this campaign used modern, timed explosives with the express aim of sowing fear in the very heart of metropolitan Britain, in order to achieve political gains.[83]

Another early terrorist group was Narodnaya Volya, founded in Russia in 1878 as a revolutionary anarchist group inspired by Sergei Nechayev and "propaganda by the deed" theorist Carlo Pisacane.[73][84][85] The group developed ideas—such as targeted killing of the 'leaders of oppression'—that were to become the hallmark of subsequent violence by small non-state groups, and they were convinced that the developing technologies of the age—such as the invention of dynamite, which they were the first anarchist group to make widespread use of[86]—enabled them to strike directly and with discrimination.[87]

Scholars of terrorism refer to four major waves of global terrorism: "the Anarchist, the Anti-Colonial, the New Left, and the Religious. The first three have been completed and lasted around 40 years; the fourth is now in its third decade."[88]

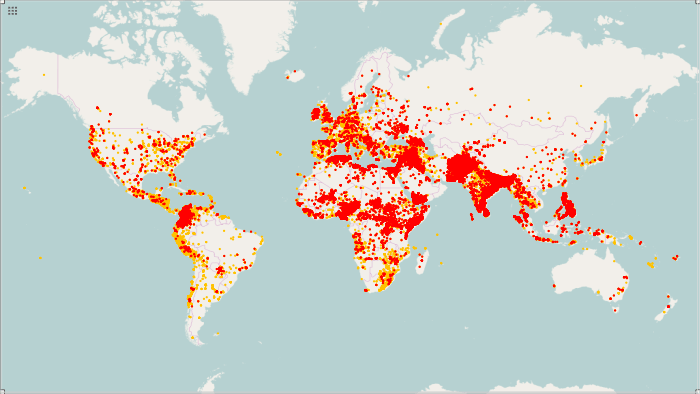

Infographics

Terrorist incidents, 1970–2015. A total of 157,520 incidents are plotted. Orange: 1970–1999, Red: 2000–2015

Terrorist incidents, 1970–2015. A total of 157,520 incidents are plotted. Orange: 1970–1999, Red: 2000–2015.png) Top 10 Countries (2000–2014)

Top 10 Countries (2000–2014) Worldwide non-state terrorist incidents 1970–2015

Worldwide non-state terrorist incidents 1970–2015

Types

Depending on the country, the political system, and the time in history, the types of terrorism are varying.

In early 1975, the Law Enforcement Assistant Administration in the United States formed the National Advisory Committee on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals. One of the five volumes that the committee wrote was titled Disorders and Terrorism, produced by the Task Force on Disorders and Terrorism under the direction of H. H. A. Cooper, Director of the Task Force staff.

The Task Force defines terrorism as "a tactic or technique by means of which a violent act or the threat thereof is used for the prime purpose of creating overwhelming fear for coercive purposes". It classified disorders and terrorism into six categories:[92]

- Civil disorder – A form of collective violence interfering with the peace, security, and normal functioning of the community.

- Political terrorism – Violent criminal behaviour designed primarily to generate fear in the community, or substantial segment of it, for political purposes.

- Non-Political terrorism – Terrorism that is not aimed at political purposes but which exhibits "conscious design to create and maintain a high degree of fear for coercive purposes, but the end is individual or collective gain rather than the achievement of a political objective".

- Quasi-terrorism – The activities incidental to the commission of crimes of violence that are similar in form and method to genuine terrorism but which nevertheless lack its essential ingredient. It is not the main purpose of the quasi-terrorists to induce terror in the immediate victim as in the case of genuine terrorism, but the quasi-terrorist uses the modalities and techniques of the genuine terrorist and produces similar consequences and reaction.[93][94][95] For example, the fleeing felon who takes hostages is a quasi-terrorist, whose methods are similar to those of the genuine terrorist but whose purposes are quite different.

- Limited political terrorism – Genuine political terrorism is characterized by a revolutionary approach; limited political terrorism refers to "acts of terrorism which are committed for ideological or political motives but which are not part of a concerted campaign to capture control of the state".

- Official or state terrorism – "referring to nations whose rule is based upon fear and oppression that reach similar to terrorism or such proportions". It may also be referred to as Structural Terrorism defined broadly as terrorist acts carried out by governments in pursuit of political objectives, often as part of their foreign policy.

Other sources have defined the typology of terrorism in different ways, for example, broadly classifying it into domestic terrorism and international terrorism, or using categories such as vigilante terrorism or insurgent terrorism.[96] One way the typology of terrorism may be defined:[97][98]

- Political terrorism

- Sub-state terrorism

- Social revolutionary terrorism

- Nationalist-separatist terrorism

- Religious extremist terrorism

- Religious fundamentalist Terrorism

- New religions terrorism

- Right-wing terrorism

- Left-wing terrorism

- State-sponsored terrorism

- Regime or state terrorism

- Sub-state terrorism

- Criminal terrorism

- Pathological terrorism

Motivations of terrorists

Attacks on 'collaborators' are used to intimidate people from cooperating with the state in order to undermine state control. This strategy was used in Ireland, in Kenya, in Algeria and in Cyprus during their independence struggles.

Attacks on high-profile symbolic targets are used to incite counter-terrorism by the state to polarize the population. This strategy was used by Al-Qaeda in its attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon in the United States on September 11, 2001. These attacks are also used to draw international attention to struggles that are otherwise unreported, such as the Palestinian airplane hijackings in 1970 and the 1975 Dutch train hostage crisis.

Abrahm suggests that terrorist organizations do not select terrorism for its political effectiveness.[99] Individual terrorists tend to be motivated more by a desire for social solidarity with other members of their organization than by political platforms or strategic objectives, which are often murky and undefined.[99] Additionally, Michael Mousseau shows possible relationships between the type of economy within a country and ideology associated with terrorism.[100] Many terrorists have a history of domestic violence.[101]

Some terrorists like Timothy McVeigh were motivated by revenge against a state for its actions against its citizens.

According to Paul Gill, John Horgan and Paige Deckert on behalf of The Department of security of UK, 43% of lone wolf terrorism is motivated by religious beliefs. The same report indicates that Just less than a third (31.9%) have pre-existing mental health disorders, while many are found to have these problems upon arrest. At least 37% lived alone at the time of their event planning and/or execution, a further 26.1% lived with others, and no data were available for the remaining cases. 40.2% were unemployed at the time of their arrest or terrorist event. Many were chronically unemployed and consistently struggled to hold any form of employment for a significant amount of time. 19.3% subjectively experienced being disrespected by others, while 14.3% experienced being the victim of verbal or physical assault. [102]

It is true that one of the main reasons behind terrorism is a strong religious belief however there are other factors such as cultural, social and political. Even though these reasons are like most around the world. The drive behind these Chechen terrorists are quite distinct and unique from others. Many of the Chechens considered themselves secular freedom fighters, nationalist insurgents seeking to establish an independent secular state of Chechnya. A distinction must be made from the beginning between national Chechen terrorists and non-Chechen fighters who have adopted the idea from abroad. Few Chechen fighters fought for the jihads although on the other hand most of the non-Chechen fighters did (Janeczko, 2014 [103]

One of the major reasons why terrorists are motivated and perhaps eager to carry out horrific acts is assurance of financial stability for their families, that they are given when they join a terrorist organization. An extra grant is provided for the families of suicide bombers.[25]

Democracy and domestic terrorism

Terrorism is most common in nations with intermediate political freedom, and it is least common in the most democratic nations.[104][105][106][107] However, one study suggests that suicide attacks may be an exception to this general rule. Evidence regarding this particular method of terrorism reveals that every modern suicide campaign has targeted a democracy–a state with a considerable degree of political freedom.[108] The study suggests that concessions awarded to terrorists during the 1980s and 1990s for suicide attacks increased their frequency.[109] There is a connection between the existence of civil liberties, democratic participation and terrorism. According to Young and Dugan, these things encourage terrorist groups to organize and generate terror.[110]

Some examples of "terrorism" in non-democratic nations include ETA in Spain under Francisco Franco (although the group's terrorist activities increased sharply after Franco's death),[111] the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in pre-war Poland,[112] the Shining Path in Peru under Alberto Fujimori,[113] the Kurdistan Workers Party when Turkey was ruled by military leaders and the ANC in South Africa.[114] Democracies, such as Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, Israel, Indonesia, India, Spain, Germany, Italy and the Philippines, have also experienced domestic terrorism.

While a democratic nation espousing civil liberties may claim a sense of higher moral ground than other regimes, an act of terrorism within such a state may cause a dilemma: whether to maintain its civil liberties and thus risk being perceived as ineffective in dealing with the problem; or alternatively to restrict its civil liberties and thus risk delegitimizing its claim of supporting civil liberties.[115] For this reason, homegrown terrorism has started to be seen as a greater threat, as stated by former CIA Director Michael Hayden.[116] This dilemma, some social theorists would conclude, may very well play into the initial plans of the acting terrorist(s); namely, to delegitimize the state and cause a systematic shift towards anarchy via the accumulation of negative sentiments towards the state system.[117]

Religious terrorism

Terrorist acts throughout history have been performed on religious grounds with the goal to either spread or enforce a system of belief, viewpoint or opinion.[119] The validity and scope of religious terrorism is limited to an individual's view or a group's view or interpretation of that belief system's teachings.

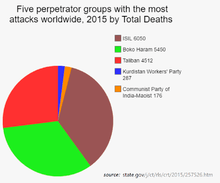

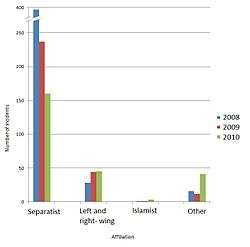

According to the Global Terrorism Index by the University of Maryland, College Park, religious extremism has overtaken national separatism and become the main driver of terrorist attacks around the world. Since 9/11 there has been a five-fold increase in deaths from terrorist attacks. The majority of incidents over the past several years can be tied to groups with a religious agenda. Before 2000, it was nationalist separatist terrorist organizations such as the IRA and Chechen rebels who were behind the most attacks. The number of incidents from nationalist separatist groups has remained relatively stable in the years since while religious extremism has grown. The prevalence of Islamist groups in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria is the main driver behind these trends.[120]

Four of the terrorist groups that have been most active since 2001 are Boko Haram, Al Qaeda, the Taliban and ISIL. These groups have been most active in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nigeria and Syria. 80% of all deaths from terrorism occurred in one of these five countries.[120]

In 2015, the Southern Poverty Law Center released a report on terrorism in the United States. The report (titled The Age of the Wolf) found that during that period, "more people have been killed in America by non-Islamic domestic terrorists than jihadists."[121] The "virulent racist and anti-semitic" ideology of the ultra-right wing Christian Identity movement is usually accompanied by anti-government sentiments.[122] Adherents of Christian Identity believe that whites of European descent can be traced back to the "Lost Tribes of Israel" and many consider Jews to be the Satanic offspring of Eve and the Serpent.[122] This group has committed hate crimes, bombings and other acts of terrorism. Its influence ranges from the Ku Klux Klan and neo-nazi groups to the anti-government militia and sovereign citizen movements.[122] Christian Identity's origins can be traced back to Anglo-Israelism. Anglo-Israelism held the view that Jews were descendants of ancient Israelites who had never been lost. By the 1930s, the movement had been infected with anti-Semitism, and eventually Christian Identity theology diverged from traditional Anglo-Israelism, and developed what is known as the "two seed" theory.[122] According to the two-seed theory, the Jewish people are descended from Cain and the serpent (not from Shem).[122] The white European seedline is descended from the "lost tribes" of Israel. They hold themselves to "God's laws", not to "man's laws", and they do not feel bound to a government that they consider run by Jews and the New World Order.[122]

Israel has also had problems with Jewish religious terrorism. Yigal Amir assassinated Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995. For Amir, killing Rabin was an exemplary act that symbolized the fight against an illegitimate government that was prepared to cede Jewish Holy Land to the Palestinians. [123]

Perpetrators

The perpetrators of acts of terrorism can be individuals, groups, or states. According to some definitions, clandestine or semi-clandestine state actors may also carry out terrorist acts outside the framework of a state of war. However, the most common image of terrorism is that it is carried out by small and secretive cells, highly motivated to serve a particular cause and many of the most deadly operations in recent times, such as the September 11 attacks, the London underground bombing, 2008 Mumbai attacks and the 2002 Bali bombing were planned and carried out by a close clique, composed of close friends, family members and other strong social networks. These groups benefited from the free flow of information and efficient telecommunications to succeed where others had failed.[124]

Over the years, much research has been conducted to distill a terrorist profile to explain these individuals' actions through their psychology and socio-economic circumstances.[125] Others, like Roderick Hindery, have sought to discern profiles in the propaganda tactics used by terrorists. Some security organizations designate these groups as violent non-state actors. A 2007 study by economist Alan B. Krueger found that terrorists were less likely to come from an impoverished background (28% vs. 33%) and more likely to have at least a high-school education (47% vs. 38%). Another analysis found only 16% of terrorists came from impoverished families, vs. 30% of male Palestinians, and over 60% had gone beyond high school, vs. 15% of the populace.A study into the poverty-stricken conditions and whether or not,terrorists are more likely to come from here,show that people who grew up in these situations tend to show aggression and frustration towards others. This theory is largely debated for the simple fact that just because one is frustrated,does not make them a potential terrorist.[25][126]

To avoid detection, a terrorist will look, dress, and behave normally until executing the assigned mission. Some claim that attempts to profile terrorists based on personality, physical, or sociological traits are not useful.[127] The physical and behavioral description of the terrorist could describe almost any normal person.[128] However, the majority of terrorist attacks are carried out by military age men, aged 16–40.[128]

Non-state groups

Groups not part of the state apparatus of in opposition to the state are most commonly referred to as a "terrorist" in the media.

According to the Global Terrorism Database, the most active terrorist group in the period 1970 to 2010 was Shining Path (with 4,517 attacks), followed by Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), Irish Republican Army (IRA), Basque Fatherland and Freedom (ETA), Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), Taliban, Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, New People's Army, National Liberation Army of Colombia (ELN), and Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).[129]

State sponsors

A state can sponsor terrorism by funding or harboring a terrorist group. Opinions as to which acts of violence by states consist of state-sponsored terrorism vary widely. When states provide funding for groups considered by some to be terrorist, they rarely acknowledge them as such.[130]

State terrorism

Civilization is based on a clearly defined and widely accepted yet often unarticulated hierarchy. Violence done by those higher on the hierarchy to those lower is nearly always invisible, that is, unnoticed. When it is noticed, it is fully rationalized. Violence done by those lower on the hierarchy to those higher is unthinkable, and when it does occur it is regarded with shock, horror, and the fetishization of the victims.

As with "terrorism" the concept of "state terrorism" is controversial.[132] The Chairman of the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Committee has stated that the Committee was conscious of 12 international Conventions on the subject, and none of them referred to State terrorism, which was not an international legal concept. If States abused their power, they should be judged against international conventions dealing with war crimes, international human rights law, and international humanitarian law.[133] Former United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan has said that it is "time to set aside debates on so-called 'state terrorism'. The use of force by states is already thoroughly regulated under international law".[134] However, he also made clear that, "regardless of the differences between governments on the question of the definition of terrorism, what is clear and what we can all agree on is that any deliberate attack on innocent civilians [or non-combatants], regardless of one's cause, is unacceptable and fits into the definition of terrorism."[135]

_burning_after_the_Japanese_attack_on_Pearl_Harbor_-_NARA_195617_-_Edit.jpg)

State terrorism has been used to refer to terrorist acts committed by governmental agents or forces. This involves the use of state resources employed by a state's foreign policies, such as using its military to directly perform acts of terrorism. Professor of Political Science Michael Stohl cites the examples that include the German bombing of London, the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, the British and American firebombing of Dresden, and the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. He argues that "the use of terror tactics is common in international relations and the state has been and remains a more likely employer of terrorism within the international system than insurgents." He also cites the first strike option as an example of the "terror of coercive diplomacy" as a form of this, which holds the world hostage with the implied threat of using nuclear weapons in "crisis management" and he argues that the institutionalized form of terrorism has occurred as a result of changes that took place following World War II. In this analysis, state terrorism exhibited as a form of foreign policy was shaped by the presence and use of weapons of mass destruction, and the legitimizing of such violent behavior led to an increasingly accepted form of this behavior by the state .[136][137][138]

Charles Stewart Parnell described William Ewart Gladstone's Irish Coercion Act as terrorism in his "no-Rent manifesto" in 1881, during the Irish Land War.[139] The concept is also used to describe political repressions by governments against their own civilian populations with the purpose of inciting fear. For example, taking and executing civilian hostages or extrajudicial elimination campaigns are commonly considered "terror" or terrorism, for example during the Red Terror or the Great Terror.[140] Such actions are also often described as democide or genocide, which have been argued to be equivalent to state terrorism.[141] Empirical studies on this have found that democracies have little democide.[142][143] Western democracies, including the United States, have supported state terrorism[144] and mass killings,[145] with some examples being the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66 and Operation Condor.[146][147][148]

Connection with tourism

The connection between terrorism and tourism has been widely studied since the Luxor massacre in Egypt.[149][150] In the 1970s, the targets of terrorists were politicians and chiefs of police while now, international tourists and visitors are selected as the main targets of attacks. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, were the symbolic epicenter, which marked a new epoch in the use of civil transport against the main power of the planet.[151] From this event onwards, the spaces of leisure that characterized the pride of West, were conceived as dangerous and frightful.[152][153]

Funding

State sponsors have constituted a major form of funding; for example, Palestine Liberation Organization, Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine and other groups considered to be terrorist organizations, were funded by the Soviet Union.[154][155] The Stern Gang received funding from Italian Fascist officers in Beirut to undermine the British Mandate for Palestine.[156] Pakistan has created and nurtured terrorist groups as policy for achieving tactical objectives against its neighbours, especially India.[157]

"Revolutionary tax" is another major form of funding, and essentially a euphemism for "protection money".[154] Revolutionary taxes "play a secondary role as one other means of intimidating the target population".[154]

Other major sources of funding include kidnapping for ransoms, smuggling (including wildlife smuggling),[158] fraud, and robbery.[154] The Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant has reportedly received funding "via private donations from the Gulf states".[159]

The Financial Action Task Force is an inter-governmental body whose mandate, since October 2001, has included combating terrorist financing.[160]

Tactics

Terrorist attacks are often targeted to maximize fear and publicity, usually using explosives or poison.[162] Terrorist groups usually methodically plan attacks in advance, and may train participants, plant undercover agents, and raise money from supporters or through organized crime. Communications occur through modern telecommunications, or through old-fashioned methods such as couriers. There is also concern about terrorist attacks employing weapons of mass destruction.

Terrorism is a form of asymmetric warfare, and is more common when direct conventional warfare will not be effective because forces vary greatly in power.[163]

The context in which terrorist tactics are used is often a large-scale, unresolved political conflict. The type of conflict varies widely; historical examples include:

- Secession of a territory to form a new sovereign state or become part of a different state

- Dominance of territory or resources by various ethnic groups

- Imposition of a particular form of government

- Economic deprivation of a population

- Opposition to a domestic government or occupying army

- Religious fanaticism

Responses

Responses to terrorism are broad in scope. They can include re-alignments of the political spectrum and reassessments of fundamental values.

Specific types of responses include:

- Targeted laws, criminal procedures, deportations, and enhanced police powers

- Target hardening, such as locking doors or adding traffic barriers

- Preemptive or reactive military action

- Increased intelligence and surveillance activities

- Preemptive humanitarian activities

- More permissive interrogation and detention policies

The term "counter-terrorism" has a narrower connotation, implying that it is directed at terrorist actors.

Response in the United States

According to a report by Dana Priest and William M. Arkin in The Washington Post, "Some 1,271 government organizations and 1,931 private companies work on programs related to counterterrorism, homeland security and intelligence in about 10,000 locations across the United States."[164]

America's thinking on how to defeat radical Islamists is split along two very different schools of thought. Republicans, typically follow what is known as the Bush Doctrine, advocate the military model of taking the fight to the enemy and seeking to democratize the Middle East. Democrats, by contrast, generally propose the law enforcement model of better cooperation with nations and more security at home.[165] In the introduction of the U.S. Army / Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Field Manual, Sarah Sewall states the need for "U.S. forces to make securing the civilian, rather than destroying the enemy, their top priority. The civilian population is the center of gravity—the deciding factor in the struggle.... Civilian deaths create an extended family of enemies—new insurgent recruits or informants––and erode support of the host nation." Sewall sums up the book's key points on how to win this battle: "Sometimes, the more you protect your force, the less secure you may be.... Sometimes, the more force is used, the less effective it is.... The more successful the counterinsurgency is, the less force can be used and the more risk must be accepted.... Sometimes, doing nothing is the best reaction."[166] This strategy, often termed "courageous restraint", has certainly led to some success on the Middle East battlefield, yet it fails to address the central truth: the terrorists we face are mostly homegrown.[165]

Terrorism research

Terrorism research, also called terrorism and counter-terrorism research, is an interdisciplinary academic field which seeks to understand the causes of terrorism, how to prevent it as well as its impact in the broadest sense. Terrorism research can be carried out in both military and civilian contexts, for example by research centres such as the British Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence, the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies, and the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT). There are several academic journals devoted to the field.[167]

Mass media

Mass media exposure may be a primary goal of those carrying out terrorism, to expose issues that would otherwise be ignored by the media. Some consider this to be manipulation and exploitation of the media.[168]

The Internet has created a new channel for groups to spread their messages.[169] This has created a cycle of measures and counter measures by groups in support of and in opposition to terrorist movements. The United Nations has created its own online counter-terrorism resource.[170]

The mass media will, on occasion, censor organizations involved in terrorism (through self-restraint or regulation) to discourage further terrorism. However, this may encourage organizations to perform more extreme acts of terrorism to be shown in the mass media. Conversely James F. Pastor explains the significant relationship between terrorism and the media, and the underlying benefit each receives from the other.[171]

There is always a point at which the terrorist ceases to manipulate the media gestalt. A point at which the violence may well escalate, but beyond which the terrorist has become symptomatic of the media gestalt itself. Terrorism as we ordinarily understand it is innately media-related.

Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher also famously spoke of the close connection between terrorism and the media, calling publicity 'the oxygen of terrorism'.[173]

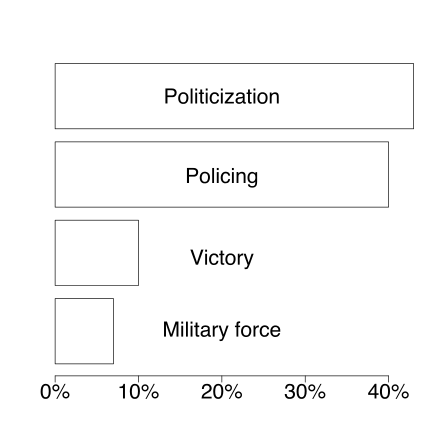

Outcome of terrorist groups

Jones and Libicki (2008) created a list of all the terrorist groups they could find that were active between 1968 and 2006. They found 648. of those, 136 splintered and 244 were still active in 2006.[175] Of the ones that ended, 43 percent converted to nonviolent political actions, like the Irish Republican Army in Northern Ireland. Law enforcement took out 40 percent. Ten percent won. Only 20 groups, 7 percent, were taken out by military force.

Forty-two groups became large enough to be labeled an insurgency; 38 of those had ended by 2006. Of those, 47 percent converted to nonviolent political actors. Only 5 percent were taken out by law enforcement. 26 percent won. 21 percent succumbed to military force.[176] Jones and Libicki concluded that military force may be necessary to deal with large insurgencies but are only occasionally decisive, because the military is too often seen as a bigger threat to civilians than the terrorists. To avoid that, the rules of engagement must be conscious of collateral damage and work to minimize it.

Another researcher, Audrey Cronin, lists six primary ways that terrorist groups end:[177]

- Capture or killing of a group's leader. (Decapitation).

- Entry of the group into a legitimate political process. (Negotiation).

- Achievement of group aims. (Success).

- Group implosion or loss of public support. (Failure).

- Defeat and elimination through brute force. (Repression).

- Transition from terrorism into other forms of violence. (Reorientation).

Databases

The following terrorism databases are or were made publicly available for research purposes, and track specific acts of terrorism:

- Global Terrorism Database, an open-source database by the University of Maryland, College Park on terrorist events around the world from 1970 through 2015 with more than 150,000 cases.

- MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base

- Worldwide Incidents Tracking System

- Tocsearch (dynamic database)

The following public report and index provides a summary of key global trends and patterns in terrorism around the world

- Global Terrorism Index, produced annually by the Institute for Economics and Peace

The following publicly available resources index electronic and bibliographic resources on the subject of terrorism

The following terrorism databases are maintained in secrecy by the United States Government for intelligence and counter-terrorism purposes:

Jones and Libicki (2008) includes a table of 268 terrorist groups active between 1968 and 2006 with their status as of 2006: still active, splintered, converted to nonviolence, removed by law enforcement or military, or won. (These data are not in a convenient machine-readable format but are available.)

See also

- Archives of Terror

- Christian terrorism

- Crimes against humanity

- Cyberterrorism

- Definitions of terrorism

- Domestic terrorism in the United States

- Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism

- Global Terrorism Index

- House of Terror

- Islamic extremism

- Islamic terrorism

- Jewish religious terrorism

- Jihadi tourism

- Khalistan movement

- List of causes of death by rate

- List of designated terrorist groups

- List of terrorist incidents

- Lynching in the United States

- Narcoterrorism

- National Counter Terrorism Security Office

- Saffron terror

- State terrorism

- Suicide attack

- Terrorism in Russia

- Terrorism and tourism in Egypt

- Terrorism in the European Union

- Victims of Acts of Terror Memorial

- War on Terror

- Violent extremism

Notes

- ↑ Fortna, Virginia Page (20 May 2015). "Do Terrorists Win? Rebels' Use of Terrorism and Civil War Outcomes". International Organization. 69 (3): 519–556. doi:10.1017/S0020818315000089. hdl:1811/52898.

- ↑ Wisnewski, J. Jeremy, ed. (18 December 2008). Torture, Terrorism, and the Use of Violence (also available as Review Journal of Political Philosophy Volume 6, Issue Number 1). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-4438-0291-8.

- ↑ Stevenson, ed. by Angus (2010). Oxford dictionary of English (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heryanto, Ariel (7 April 2006). State Terrorism and Political Identity in Indonesia: Fatally Belonging. Routledge. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-134-19569-5.

- ↑ Faimau, Gabriel (26 July 2013). Socio-Cultural Construction of Recognition: The Discursive Representation of Islam and Muslims in the British Christian News Media. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4438-5104-6.

- ↑ Campo, Juan Eduardo (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. Infobase Publishing. p. xxii. ISBN 978-1-4381-2696-8.

- ↑ Halibozek, Edward P.; Jones, Andy; Kovacich, Gerald L. (2008). The corporate security professional's handbook on terrorism (illustrated ed.). Elsevier (Butterworth-Heinemann). pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-7506-8257-2. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Robert Mackey (20 November 2009). "Can Soldiers Be Victims of Terrorism?". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

Terrorism is the deliberate killing of innocent people, at random, in order to spread fear through a whole population and force the hand of its political leaders.

- 1 2 Sinclair, Samuel Justin; Antonius, Daniel (7 May 2012). The Psychology of Terrorism Fears. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-538811-4.

- 1 2 White, Jonathan R. (1 January 2016). Terrorism and Homeland Security. Cengage Learning. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-305-63377-3.

- 1 2 Ruthven, Malise; Nanji, Azim (24 April 2017). Historical Atlas of Islam. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01385-8.

- ↑ "Terrorism". Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 3. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- ↑ Schwenkenbecher, Anne (13 August 2012). Terrorism: A Philosophical Enquiry. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-230-36398-4.

- 1 2 "The Illusion of War: Is Terrorism a Criminal Act or an Act of War? – Mackenzie Institute". Mackenzie Institute. 31 July 2014. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ Eviatar, Daphne (13 June 2013). "Is 'Terrorism' a War Crime Triable by Military Commission? Who Knows?". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- ↑ "Global Terrorism Index 2015" (PDF). Institute for Economics and Peace. p. 33.

- 1 2 Fine, Jonathan (2010). "Political and Philological Origins of the Term 'Terrorism' from the Ancient Near East to Our Times". Middle Eastern Studies. 46 (2): 271–288. JSTOR 20720662.

- ↑ Palmer, R.R. (2014). "The French Directory Between Extremes". The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760–1800. Princeton University Press. JSTOR j.ctt5hhrg5.29.

- ↑ Kellner, Douglas (April 2004). "9/11, spectacles of terror, and media manipulation: A critique of Jihadist and Bush media politics". Critical Discourse Studies. 1 (1): 41–64. doi:10.1080/17405900410001674515. eISSN 1740-5912. ISSN 1740-5904.

- 1 2 Ken Duncan (2011). "A Blast from the Past Lessons from a Largely Forgotten Incident of State-Sponsored Terrorism". Perspectives on Terrorism. 5 (1): 3–21. JSTOR 26298499.

- ↑ Crawford, Joseph (2013-09-12). Gothic Fiction and the Invention of Terrorism: The Politics and Aesthetics of Fear in the Age of the Reign of Terror. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4725-0912-3.

- ↑ Houen, Alex (2002-09-12). "Introduction". Terrorism and Modern Literature: From Joseph Conrad to Ciaran Carson. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-154198-8.

- ↑ Thackrah, John Richard (2013-09-05). Dictionary of Terrorism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-16595-6.

- ↑ Edmund Burke – To The Earl Fitzwilliam (Christmas, 1795.) In: Edmund Burke, Select Works of Edmund Burke, vol. 3 (Letters on a Regicide Peace) (1795). Retrieved 10 July 2017.

This Internet version contains two, mingled, indications of page numbers: one with single brackets like [260], one with double brackets like [ [309] ]. Burke lengthily introduces his view on 'this present Directory government', and then writes on page [ [359] ]: "Those who arbitrarily erected the new building out of the old materials of their own Convention, were obliged to send for an Army to support their work. (…) At length, after a terrible struggle, the Troops prevailed over the Citizens. (…) This power is to last as long as the Parisians think proper. (…) [315] To secure them further, they have a strong corps of irregulars, ready armed. Thousands of those Hell-hounds called Terrorists, whom they had shut up in Prison on their last Revolution, as the Satellites of Tyranny, are let loose on the people. (…)" - 1 2 3 Arie W. Kruglanski and Shira Fishman Current Directions in Psychological Science Vol. 15, No. 1 (Feb., 2006), pp. 45–48

- ↑ Bruce Hoffman, Inside Terrorism, 2 ed., Columbia University Press, 2006, p. 34.

- 1 2 Jenny Teichman (1989). "How to Define Terrorism". Philosophy. 64 (250): 505–517. JSTOR 3751606.

- ↑ Wahnich, Sophie (2016). In Defence of the Terror: Liberty or Death in the French Revolution (Reprint ed.). Verso. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-78478-202-3.

- ↑ Scurr, Ruth (17 August 2012). "In Defence of the Terror: Liberty or Death in the French Revolution by Sophie Wahnich – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ↑ James, Paul; Friedman, Jonathan (2006). Globalization and Violence, Vol. 3: Globalizing War and Intervention. London: Sage Publications. p. xxx. ; and Nairn, Tom; James, Paul (2005). Global Matrix: Nationalism, Globalism and State-Terrorism. London and New York: Pluto Press.

- ↑ "UN Reform". United Nations. 21 March 2005. Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

The second part of the report, entitled "Freedom from Fear backs the definition of terrorism–an issue so divisive agreement on it has long eluded the world community–as any action "intended to cause death or serious bodily harm to civilians or non-combatants with the purpose of intimidating a population or compelling a government or an international organization to do or abstain from doing any act"

- ↑ Hoffman (1998), p. 32, See review in The New York Times Inside Terrorism.

- ↑ "Radicalisation, De-Radicalisation, Counter-Radicalisation: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review". The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague (ICCT). 27 March 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ↑ Angus Martyn, The Right of Self-Defence under International Law-the Response to the Terrorist Attacks of 11 September, Australian Law and Bills Digest Group, Parliament of Australia Web Site, 12 February 2002. Archived 16 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Diaz-Paniagua (2008), Negotiating terrorism: The negotiation dynamics of four UN counter-terrorism treaties, 1997–2005, p. 47.

- ↑ 1994 United Nations Declaration on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism annex to UN General Assembly resolution 49/60, "Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism", of December 9, 1994, UN Doc. A/Res/60/49.

- ↑ "22 U.S. Code § 2656f – Annual country reports on terrorism". LII / Legal Information Institute.

- ↑ Bockstette, Carsten (2008). "Jihadist Terrorist Use of Strategic Communication Management Techniques" (PDF). George C. Marshall Center Occasional Paper Series (20). ISSN 1863-6039. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ↑ Juergensmeyer, Mark (2000). Terror in the Mind of God. University of California Press. pp. 125–35.

- ↑ "Number of Terrorist Attacks, Fatalities". The Washington Post. 12 June 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

The nation's deadliest terrorist acts – attacks designed to achieve a political goal

- ↑ "Terrorism in the United States 1999" (PDF). Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ "/Iraq accuses US of state terrorism". BBC News. 20 February 2002. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

Iraq has accused the United States of state terrorism amid signs that the war of words between the two countries is heating up.

- ↑ Barak Mendelsohn (January 2005). "Sovereignty under attack: the international society meets the Al Qaeda network (abstract)". Cambridge Journals. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

This article examines the complex relations between a violent non-state actor, the Al Qaeda network, and order in the international system. Al Qaeda poses a challenge to the sovereignty of specific states but it also challenges the international society as a whole.

- ↑ Khan, Ali (8 October 2006). "A Theory of International Terrorism". Connecticut Law Review. 19: 945 – via Social Science Research Network.

- 1 2 Paul Reynolds; quoting David Hannay; Former UK ambassador (14 September 2005). "UN staggers on road to reform". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

This would end the argument that one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter ...

- 1 2 Rodin, David (2006). "Terrorism". In E. Craig (Ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Peter Steinfels (1 March 2003). "Beliefs; The just-war tradition, its last-resort criterion and the debate on an invasion of Iraq". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

For those like Professor Walzer who value the just-war tradition as a disciplined way to think about the morality of war ...

- ↑ Bruce Hoffman (1998). "Inside Terrorism". Columbia University Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-231-11468-0. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

Google cached copy

- ↑ Bruce Hoffman (1998). "Inside Terrorism". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

- ↑ Raymond Bonner (1 November 1998). "Getting Attention: A scholar's historical and political survey of terrorism finds that it works". The New York Times: Books. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

Inside Terrorism falls into the category of 'must read,' at least for anyone who wants to understand how we can respond to international acts of terror.

- ↑ Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army Archived March 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Britannica Concise.

- ↑ Dr Chris Clark "Malayan Emergency, 16 June 1948". Archived from the original on 8 June 2007. , 16 June 2003.

- ↑ Ronald Reagan, speech to National Conservative Political Action Conference Archived 20 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. 8 March 1985. On the Spartacus Educational web site.

- ↑ "President Meets with Afghan Interim Authority Chairman". Georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. 29 January 2002. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ President Discusses Progress in War on Terrorism to National Guard White House web site 9 February 2006.

- ↑ "An unbiased look at terrorism in Afghanistan [in 2009] reveals that many of these 'terrorists' individuals or groups were once 'freedom fighters' struggling against the Soviets during the 1980s." (Chouvy, Pierre-Arnaud (2009). Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy (illustrated, reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-674-05134-8. )

- ↑ Sudha Ramachandran Death behind the wheel in Iraq Asian Times, 12 November 2004, "Insurgent groups that use suicide attacks therefore do not like their attacks to be described as suicide terrorism. They prefer to use terms like "martyrdom ..."

- ↑ Alex Perry How Much to Tip the Terrorist? Time, 26 September 2005. "The Tamil Tigers would dispute that tag, of course. Like other guerrillas and suicide bombers, they prefer the term "freedom fighters".

- ↑ Terrorism: concepts, causes, and conflict resolution George Mason University Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, Printed by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, Fort Belvoir, Virginia, January 2003.

- ↑ Quinney, Nigel; Coyne, A. Heather (2011). Peacemaker's Toolkit Talking to Groups that Use Terrorism (PDF). United States Institute of Peace. ISBN 978-1-60127-072-6. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ↑ Theodore P. Seto The Morality of Terrorism Includes a list in The Times published on 23 July 1946, which were described as Jewish terrorist actions, including those launched by Irgun, of which Begin was a leading member.

- ↑ BBC News: Profiles: Menachem Begin BBC website "Under Begin's command, the underground terrorist group Irgun carried out numerous acts of violence."

- ↑ Eqbal Ahmad "Straight talk on terrorism" Monthly Review, January 2002. "including Menachem Begin, appearing in "Wanted" posters saying, "Terrorists, reward this much." The highest reward I have seen offered was 100,000 British pounds for the head of Menachem Begin". "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 2006-09-10.

- ↑ Lord Desai Hansard, House of Lords Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. 3 September 1998 : Column 72, "However, Jomo Kenyatta, Nelson Mandela and Menachem Begin—to give just three examples—were all denounced as terrorists but all proved to be successful political leaders of their countries and good friends of the United Kingdom."

- ↑ BBC NEWS:World: Americas: UN reforms receive mixed response BBC website "Of all groups active in recent times, the ANC perhaps represents best the traditional dichotomous view of armed struggle. Once regarded by western governments as a terrorist group, it now forms the legitimate, elected government of South Africa, with Nelson Mandela one of the world's genuinely iconic figures."

- ↑ BBC NEWS: World: Africa: Profile: Nelson Mandela BBC website "Nelson Mandela remains one of the world's most revered statesman".

- ↑ Beckford, Martin (30 November 2010). "Hunt WikiLeaks founder like al-Qaeda and Taliban Leaders". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ MacAskill, Ewen (19 December 2010). "Julian Assange like a hi-tech terrorist". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ↑ "Quinn v. Robinson, 783 F2d. 776 (9th Cir. 1986)". Uniset.ca. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- ↑ Zachary E. McCabe (25 August 2003). "Northern Ireland: The paramilitaries, Terrorism, and September 11th" (PDF). Queen's University Belfast School of Law. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2007.

- ↑ "Guardian and Observer style guide: T". The Guardian. London. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- ↑ "BBC Editorial Guidelines on Language when Reporting Terrorism". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- 1 2 "PM Modi's vow to avenge Uri won't remain just words: Manohar Parrikar – Times of India". indiatimes.com.

- ↑ Hoffman, Bruce. Inside Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988. p. 83

- ↑ Chaliand, Gerard. The History of Terrorism: From Antiquity to al Qaeda. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. p.56

- ↑ Chaliand, Gerard. The History of Terrorism: From Antiquity to al Qaeda. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. p.68

- ↑ Hoffman, Bruce. Inside Terrorism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988. p. 167

- 1 2 3 Crenshaw, Martha, Terrorism in Context, p. 38.

- ↑ "Terrorism: From the Fenians to Al Qaeda". Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ Irish Freedom, by Richard English Publisher: Pan Books (2 November 2007), ISBN 0-330-42759-8 p179

- ↑ Irish Freedom, by Richard English Publisher: Pan Books (2 November 2007), ISBN 0-330-42759-8 p. 180

- ↑ Whelehan, Niall (2012). The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World 1867–1900. Cambridge.

- ↑ "The Fenian Dynamite campaign 1881–85". Retrieved 2012-12-17.

- ↑ History of Terrorism article by Mark Burgess Archived 11 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hoffman 1998, p. 5

- ↑ A History of Terrorism, by Walter Laqueur, Transaction Publishers, 2000, ISBN 0-7658-0799-8, p. 92

- ↑ "BBC – History – The Changing Faces of Terrorism". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ "Terrorism as a Global Wave Phenomenon: Overview". Politics.oxfordre.com. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-299 (inactive 2018-09-08). Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ "TE-SAT 2011 EU Terrorism Situation and Trend Report" (PDF). Europol. 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ "TE-SAT 2010 Terrorism Situation and Trend Report" (PDF). Europol. 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ "TE-SAT 2009 Terrorism Situation and Trend Report" (PDF). Europol. 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ "Disorders and Terrorism" (PDF). National Advisory Committee on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals. 1976. pp. 3–6.

- ↑ "Quasi-terrorism". Mukkulreddy.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2016-07-13.

- ↑ "Types of Terrorism". Crime Museum. Retrieved 2016-07-13.

- ↑ "TERRORISM". Earth Dashboard. Retrieved 2016-07-13.

- ↑ Philip P. Purpura (2007). Terrorism and homeland security: an introduction with applications. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-0-7506-7843-8.

- ↑ Hudson, Rex A. Who Becomes a Terrorist and Why: The 1999 Government Report on Profiling Terrorists, Federal Research Division, The Lyons Press, 2002.

- ↑ Barry Scheider, Jim Davis, Avoiding the abyss: progress, shortfalls and the way ahead in combatting the WMD threat, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2009 p. 60.

- 1 2 Abrahms, Max (March 2008). "What Terrorists Really Want: Terrorist Motives and Counterterrorism Strategy" (PDF 1933 KB). International Security. 32 (4): 86–89. doi:10.1162/isec.2008.32.4.78. ISSN 0162-2889. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ↑ Mousseau, Michael (2002). "Market Civilization and its Clash with Terror". International Security. 27 (3): 5–29. doi:10.1162/01622880260553615.

- ↑ Many terrorists' first victims are their wives – but we're not allowed to talk about that New Statesman

- ↑ Gill, Paul; Horgan, John; Deckert, Paige (March 1, 2014). "Bombing Alone: Tracing the Motivations and Antecedent Behaviors of Lone-Actor Terrorists,". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 59 (2): 425–435. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12312. PMC 4217375. PMID 24313297.

- ↑ Janeczko, Matthew (19 Jun 2014). "'Faced with death, even a mouse bites': Social and religious motivations behind terrorism in Chechnya": 428–456.

- ↑ "Freedom squelches terrorist violence: Harvard Gazette Archives". Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Freedom squelches terrorist violence: Harvard Gazette Archives" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism" (PDF). 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ "Unemployment, Inequality and Terrorism: Another Look at the Relationship between Economics and Terrorism" (PDF). 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ Bruce Hoffman (June 2003). "The Logic of Suicide Terrorism". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

The terrorists appear to be deliberately homing in on the few remaining places where Israelis thought they could socialize in peace.

- ↑ Pape, Robert A. "The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism", American Political Science Review, 2003. 97 (3): pp. 1–19.

- ↑ Young, Joseph K.; Dugan, Laura. "Survival of the Fittest: Why Terrorist Groups Endure". Perspectives on Terrorism. 8 (2). ISSN 2334-3745. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Basque Terrorist Group Marks 50th Anniversary with New Attacks". Time. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

Europe's longest-enduring terrorist group. This week, ETA (the initials stand for Basque Homeland and Freedom in Euskera, the Basque language)

- ↑ Timothy Snyder. A fascist hero in democratic Kiev. NewYork Reviev of Books. 24 February 2010

- ↑ Romero, Simon (18 March 2009). "Shining Path". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

The Shining Path, a faction of Peruvian militants, has resurfaced in the remote corners of the Andes. The war against the group, which took nearly 70,000 lives, supposedly ended in 2000. ... In the 1980s, the rebels were infamous for atrocities like planting bombs on donkeys in crowded markets, assassinations and other terrorist tactics.

- ↑ "1983: Car bomb in South Africa kills 16". BBC. 20 May 2005. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

The outlawed anti-apartheid group the African National Congress has been blamed for the attack ... He said the explosion was the "biggest and ugliest" terrorist incident since anti-government violence began in South Africa 20 years ago.

- ↑ Rick Young (16 May 2007). "PBS Frontline: 'Spying on the Home Front'". PBS: Frontline. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

... we and Frontline felt that it was important to look more comprehensively at the post-9/11 shift to prevention and the dilemma we all now face in balancing security and privacy.

- ↑ Yager, Jordy (25 July 2010). "Former intel chief: Homegrown terrorism is a devil of a problem". thehill.com.

- ↑ shabad, goldie and francisco jose llera ramo. "Political Violence in a Democratic State", Terrorism in Context. Ed. Martha Crenshaw. University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 1995. pp. 467.

- ↑ "Pakistan: A failed state or a clever gambler?". BBC News. 7 May 2011.

- ↑ Peter Rose (28 August 2003). "Disciples of religious terrorism share one faith". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

Almost everyone Stern interviewed said they were doing God's will, defending the faithful against the lies and evil deeds of their enemies. Such testimonials, she suggests, "often mask a deeper kind of angst and a deeper kind of fear – fear of a godless universe, of chaos, of loose rules, and of loneliness".

- 1 2 George Arnett (19 November 2014). "Religious extremism main cause of terrorism, according to report". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ Ryan Lenz (February 2015). Age of the Wolf (PDF) (Report). Southern Poverty Law Center. p. 4. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

A large number of independent studies have agreed that since the 9/11 mass murder, more people have been killed in America by non-Islamic domestic terrorists than jihadists.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "". Anti-Defamation League 2017.

- ↑ Spaaij 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Sageman, Mark (2004). Understanding Terror Networks. Philadelphia, PA: U. of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 166–67. ISBN 978-0-8122-3808-2.

- ↑ Prof. Dr. Edwin Bakker; Jeanine de Roy van Zuijdewijn (29 February 2016). "Personal Characteristics of Lone-Actor Terrorists". Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ↑ Steven D. Levitt; Stephen J. Dubner (2009). Superfreakonomics: global cooling, patriotic prostitutes, and why suicide bombers should buy life insurance. William Morrow. pp. 62, 231. ISBN 978-0-06-088957-9. citing Alan B. Krueger, What Makes a Terrorist (Princeton University Press 2007); Claude Berrebi, "Evidence About the Link Between Education, Poverty, and Terrorism among Palestinians", Princeton University Industrial Relations Section Working paper, 2003 and Krueger and Jita Maleckova, "Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection?" Journal of Economic Perspectives 17 no. 4 Fall 2003 / 63.

- ↑ Sean Coughlan (21 August 2006). "Fear of the unknown". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-01-11.

A passenger on the flight, Heath Schofield, explained the suspicions: "It was a return holiday flight, full of people in flip-flops and shorts. There were just two people in the whole crowd who looked like they didn't belong there."

- 1 2 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division The Sociology and Psychology of Terrorism.

- ↑ https://www.start.umd.edu/sites/default/files/files/publications/br/ETACeasefires.pdf

- ↑ "State Sponsored Terrorism". trackingterrorism.org. Retrieved 2017-05-28.

- ↑ Endgame: Resistance, by Derrick Jensen, Seven Stories Press, 2006, ISBN 1-58322-730-X, p. ix.

- ↑ "Pds Sso" (PDF). Eprints.unimelb.edu.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ "Addressing Security Council, Secretary-General Calls on Counter-Terrorism Committee To Develop Long-Term {{subst:lc:Strategy}} To Defeat Terror". Un.org. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ Lind, Michael (May 2, 2005). "The Legal Debate is Over: Terrorism is a War Crime | The New America Foundation". Newamerica.net. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved August 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Press conference with Kofi Annan & FM Kamal Kharrazi". Un.org. 26 January 2002. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ Michael Stohl (1 April 1984). "The Superpowers and International Terror". International Studies Association, Atlanta.

- ↑ Michael Stohl (1988). "Terrible beyond Endurance? The Foreign Policy of State Terrorism". International Studies Association, Atlanta.

- ↑ Michael Stohl (1984). "The State as Terrorist: The Dynamics of Governmental Violence and Repression". International Studies Association, Atlanta. p. 49.

- ↑ "The "No Rent" Manifesto.; Text of the Document Issued by the Land League". The New York Times. 2 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

- ↑ Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stéphane Courtois, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, hardcover, 858 pages, ISBN 0-674-07608-7

- ↑ Kisangani, E.; Nafziger, E. Wayne (2007). "The Political Economy of State Terror" (PDF). Defence and Peace Economics. 18 (5): 405–414. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.579.1472. doi:10.1080/10242690701455433. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ↑ Death by Government by R.J. Rummel New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1994. Online links:

- ↑ No Lessons Learned from the Holocaust?, Barbara Harff, 2003. Archived 30 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Blakeley, Ruth (2009). State Terrorism and Neoliberalism: The North in the South. Routledge. pp. 4, 20-23, 88. ISBN 978-0415686174.

- ↑ Valentino, Benjamin A. (2005). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0801472732.

- ↑ Simpson, Bradley (2010). Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.–Indonesian Relations, 1960–1968. Stanford University Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0804771825.

Washington did everything in its power to encourage and facilitate the army-led massacre of alleged PKI members, and U.S. officials worried only that the killing of the party's unarmed supporters might not go far enough, permitting Sukarno to return to power and frustrate the [Johnson] Administration's emerging plans for a post-Sukarno Indonesia. This was efficacious terror, an essential building block of the neoliberal policies that the West would attempt to impose on Indonesia after Sukarno's ouster

- ↑ Mark Aarons (2007). "Justice Betrayed: Post-1945 Responses to Genocide." In David A. Blumenthal and Timothy L. H. McCormack (eds). The Legacy of Nuremberg: Civilising Influence or Institutionalised Vengeance? (International Humanitarian Law). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004156917 pp. 71 & 80–81

- ↑ McSherry, J. Patrice (2011). "Chapter 5: "Industrial repression" and Operation Condor in Latin America". In Esparza, Marcia; Henry R. Huttenbach; Daniel Feierstein. State Violence and Genocide in Latin America: The Cold War Years (Critical Terrorism Studies). Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-415-66457-8.

- ↑ Sönmez, S. F.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Tarlow, P. (1999). "Tourism in crisis: Managing the effects of terrorism" (PDF). Journal of Travel Research. 38 (1): 13–18. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.465.286. doi:10.1177/004728759903800104.

- ↑ Tarlow, P. E. (2006). "Tourism and Terrorism". In Wilks J, Pendergast D & Leggat P. (Eds) Tourism in turbulent times: Towards safe experiences for visitors (Advances in Tourism Research), Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 80–82.