Rajput

| Rajput | |

|---|---|

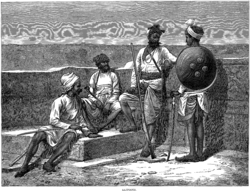

An 1876 engraving of the Rajputs of Rajputana, from the Illustrated London News | |

| Religions | Hinduism, Islam[1][2][3] and Sikhism |

| Languages | Hindi, Haryanvi, Punjabi, Bhojpuri,[4] Urdu, Gujarati, Maithili,[5] Marwari, Mewari, Sindhi, Bengali, Nepali, Dogri and Pahari |

| Region | Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Azad Kashmir, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra[6], West Bengal, Sindh, Nepal and West Punjab |

Rajput (from Sanskrit raja-putra, "son of a king") is a large multi-component cluster of castes, kin bodies, and local groups, sharing social status and ideology of genealogical descent originating from the Indian subcontinent. The term Rajput covers various patrilineal clans historically associated with warriorhood: several clans claim Rajput status, although not all claims are universally accepted.

The term "Rajput" acquired its present meaning only in the 16th century, although it is also anachronistically used to describe the earlier lineages that emerged in northern India from 6th century onwards. In the 11th century, the term "rajaputra" appeared as a non-hereditary designation for royal officials. Gradually, the Rajputs emerged as a social class comprising people from a variety of ethnic and geographical backgrounds. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the membership of this class became largely hereditary, although new claims to Rajput status continued to be made in the later centuries. Several Rajput-ruled kingdoms played a significant role in many regions of central and northern India until the 20th century.

The Rajput population and the former Rajput states are found in north, west and central India. These areas include Rajasthan, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Jammu, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Bihar. In Pakistan they are found on the eastern parts of the country, Punjab and Sindh.

History

Origins

The origin of the Rajputs has been a much-debated topic among the historians. Colonial-era writers characterised them as descendants of the foreign invaders such as the Scythians or the Hunas, and believed that the Agnikula myth was invented to conceal their foreign origin.[7] According to this theory, the Rajputs originated when these invaders were assimilated into the Kshatriya category during the 6th or 7th century, following the collapse of the Gupta Empire.[8][9] While many of these colonial writers propagated this foreign-origin theory in order to legitimise the colonial rule, the theory was also supported by some Indian scholars, such as D. R. Bhandarkar.[7] The Indian nationalist historians, such as C. V. Vaidya, believed the Rajputs to be descendants of the ancient Vedic Aryan Kshatriyas.[10] A third group of historians, which includes Jai Narayan Asopa, theorized that the Rajputs were Brahmins who became rulers.[11]

However, recent research suggests that the Rajputs came from a variety of ethnic and geographical backgrounds.[12] The root word "rajaputra" (literally "son of a king") first appears as a designation for royal officials in the 11th century Sanskrit inscriptions. According to some scholars, it was reserved for the immediate relatives of a king; others believe that it was used by a larger group of high-ranking men.[13] Over time, the derivative term "Rajput" came to denote a hereditary political status, which was not necessarily very high: the term could denote a wide range of rank-holders, from an actual son of a king to the lowest-ranked landholder.[14] Before the 15th century, the term "Rajput" was associated with people of mixed-caste origin, and was therefore considered inferior in rank to "Kshatriya".[15]

Gradually, the term Rajput came to denote a social class, which was formed when the various tribal and nomadic groups became landed aristocrats, and transformed into the ruling class.[16] These groups assumed the title "Rajput" as part of their claim to higher social positions and ranks.[17] The early medieval literature suggests that this newly formed Rajput class comprised people from multiple castes.[18] Thus, the Rajput identity is not the result of a shared ancestry. Rather, it emerged when different social groups of medieval India sought to legitimize their newly acquired political power by claiming Kshatriya status. These groups started identifying as Rajput at different times, in different ways.[19]

Emergence as a community

Scholarly opinions differ on when the term Rajput acquired hereditary connotations and came to denote a clan-based community. Historian Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya, based on his analysis of inscriptions (primarily from Rajasthan), believed that by the 12th century, the term "rajaputra" was associated with fortified settlements, kin-based landholding, and other features that later became indicative of the Rajput status.[13] According to Chattopadhyaya, the title acquired "an element of heredity" from c. 1300.[20] A later study by of 11th-14th century inscriptions from western and central India, by Michael B. Bednar, concludes that the designations such as "rajaputra", "thakkura" and "rauta" were not necessarily hereditary during this period.[20]

During its formative stages, the Rajput class was quite assimilative and absorbed people from a wide range of lineages.[16] However, by the late 16th century, it had become genealogically rigid, based on the ideas of blood purity.[21] The membership of the Rajput class was now largely inherited rather than acquired through military achievements.[20] A major factor behind this development was the consolidation of the Mughal Empire, whose rulers had great interest in genealogy. As the various Rajput chiefs became Mughal feduatories, they no longer engaged in major conflicts with each other. This decreased the possibility of achieving prestige through military action, and made hereditary prestige more important.[22]

The word "Rajput" thus acquired its present-day meaning in the 16th century.[23][24] During 16th and 17th centuries, the Rajput rulers and their bards (charans) sought to legitimize the Rajput socio-political status on the basis of descent and kinship.[25] They fabricated genealogies linking the Rajput families to the ancient dynasties, and associated them with myths of origins that established their Kshatriya status.[20][26] This led to the emergence of what Indologist Dirk Kolff calls the "Rajput Great Tradition", which accepted only hereditary claims to the Rajput identity, and fostered a notion of eliteness and exclusivity.[27] The legendary epic poem Prithviraj Raso, which depicts warriors from several different Rajput clans as associates of Prithviraj Chauhan, fostered a sense of unity among these clans.[28] The text thus contributed to the consolidation of the Rajput identity by offering these clans a shared history.[13]

Despite these developments, migrant soldiers made new claims to the Rajput status until as late as the 19th century.[21] In the 19th century, the colonial administrators of India re-imagined the Rajputs as similar to the Anglo-Saxon knights. They compiled the Rajput genealogies in the process of settling land disputes, surveying castes and tribes, and writing history. These genealogies became the basis of distinguishing between the "genuine" and the "spurious" Rajput clans.[29]

Rajput kingdoms

The Rajput kingdoms were disparate: loyalty to a clan was more important than allegiance to the wider Rajput social grouping, meaning that one clan would fight another. This and the internecine jostling for position that took place when a clan leader (raja) died meant that Rajput politics were fluid and prevented the formation of a coherent Rajput empire.[30]

The first major Rajput kingdom was the Sisodia-ruled kingdom of Mewar.[12] However, the term "Rajput" has also been used as an anachronistic designation for the earlier Hindu dynasties that succeeded the Gurjara-Pratiharas, such as the Chahamanas (of Shakambhari, Nadol and Jalor), the Tomaras, the Chaulukyas, the Paramaras, the Gahadavalas, and the Chandelas.[31][32] These dynasties confronted the Ghaznavid and Ghurid invaders during the 11th and 12th centuries. Although the Rajput identity did not exist at this time, these lineages were classified as aristocratic Rajput clans in the later times.[33]

In the 15th century, the Muslim sultans of Malwa and Gujarat put a joint effort to overcome the Mewar ruler Rana Kumbha but both the sultans were defeated.[34] Subsequently, in 1518 the Rajput Mewar Kingdom under Rana Sanga achieved a major victory over Sultan Ibrahim Lodhi of Delhi Sultanate and afterwards Rana's influence extended up to the striking distance of Pilia Khar in Agra.[35][36] Accordingly, Rana Sanga came to be the most distinguished indigenous contender for supremacy but was defeated by the Mughal invader Babur at Battle of Khanwa in 1527.[37]

From as early as the 16th century, Purbiya Rajput soldiers from the eastern regions of Bihar and Awadh, were recruited as mercenaries for Rajputs in the west, particularly in the Malwa region.[38]

Mughal period

Akbar's policy (Akbar - Shah Jahan)

After the mid-16th century, many Rajput rulers formed close relationships with the Mughal emperors and served them in different capacities.[39][40] It was due to the support of the Rajputs that Akbar was able to lay the foundations of the Mughal empire in India.[41] Some Rajput nobles gave away their daughters in marriage to Mughal emperors and princes for political motives.[42][43][44][45] For example, Akbar accomplished 40 marriages for him, his sons and grandsons, out of which 17 were Rajput-Mughal alliances.[46] Akbar's successors as Mogul emperors, his son Jahangir and grandson Shah Jahan had Rajput mothers.[47] The ruling Sisodia Rajput family of Mewar made it a point of honour not to engage in matrimonial relationships with Mughals and thus claimed to stand apart from those Rajput clans who did so.[48]

Aurangzeb's policy

Akbar's diplomatic policy regarding the Rajputs was later damaged by the intolerant rules introduced by his great-grandson Aurangzeb. A prominent example of these rules included the re-imposition of Jaziya, which had been abolished by Akbar.[41] However, despite imposition of Jaziya Aurangzeb's army had a high proportion of Rajput officers in the upper ranks of the imperial army and they were all exempted from paying Jaziya[49] The Rajputs then revolted against the Mughal empire. Aurangzeb's conflicts with the Rajputs, which commenced in the early 1680s, henceforth became a contributing factor towards the downfall of the Mughal empire.[50][41]

In the 18th century, the Rajputs came under influence of the Maratha empire.[50][51][52] By the late 18th century, the Rajput rulers begin negotiations with the East India Company and by 1818 all the Rajput states had formed an alliance with the company.[53]

British colonial period

The medieval bardic chronicles (kavya and masnavi) glorified the Rajput past, presenting warriorhood and honour as Rajput ideals. This later became the basis of the British reconstruction of the Rajput history and the nationalist interpretations of Rajputs' struggles with the Muslim invaders.[54] James Tod, a British colonial official, was impressed by the military qualities of the Rajputs but is today considered to have been unusually enamoured of them. Although the group venerate him to this day, he is viewed by many historians since the late nineteenth century as being a not particularly reliable commentator.[55][56] Jason Freitag, his only significant biographer, has said that Tod is "manifestly biased".[57]

The Rajput practices of female infanticide and sati (widow immolation) were other matters of concern to the British. It was believed that the Rajputs were the primary adherents to these practices, which the British Raj considered savage and which provided the initial impetus for British ethnographic studies of the subcontinent that eventually manifested itself as a much wider exercise in social engineering.[59]

In reference to the role of the Rajput soldiers serving under the British banner, Captain A. H. Bingley wrote:

Rajputs have served in our ranks from Plassey to the present day (1899). They have taken part in almost every campaign undertaken by the Indian armies. Under Forde they defeated the French at Condore. Under Monro at Buxar they routed the forces of the Nawab of Oudh. Under Lake they took part in the brilliant series of victories which destroyed the power of the Marathas.[60]

Independent India

On India's independence in 1947, the princely states, including those of the Rajput, were given three options: join either India or Pakistan, or remain independent. Rajput rulers of the 22 princely states of Rajputana acceded to newly independent India, amalgamated into the new state of Rajasthan in 1949–1950.[61] Initially the maharajas were granted funding from the Privy purse in exchange for their acquiescence, but a series of land reforms over the following decades weakened their power, and their privy purse was cut off during Indira Gandhi's administration under the 1971 Constitution 26th Amendment Act. The estates, treasures, and practices of the old Rajput rulers now form a key part of Rajasthan's tourist trade and cultural memory.[62]

In 1951, the Rajput Rana dynasty of Nepal came to an end, having been the power behind the throne of the Shah dynasty figureheads since 1846.[63]

The Rajput Dogra dynasty of Kashmir and Jammu also came to an end in 1947.[64] though title was retained until monarchy was abolished in 1971 by the 26th amendment to the Constitution of India.[65]

The Rajputs, in states such as Madhya Pradesh are today considered to be a Forward Caste in India's system of positive discrimination. This means that they have no access to reservations here. But they are classified as an Other Backward Class by the National Commission for Backward Classes in the state of Karnataka.[66][67][68] [69] However, some Rajputs too like other agricultural castes demand reservations in Government jobs, which so far is not heeded to by the Government of India.[70][71][72][73]

Subdivisions

"Rajput" is a vaguely-defined term, and there is no universal consensus on which clans make up the Rajput community.[74] In medieval Rajasthan (the historical Rajputana) and its neighbouring areas, the word Rajput came to be restricted to certain specific clans, based on patrilineal descent and intermarriages. On the other hand, the Rajput communities living in the region to the east of Rajasthan had a fluid and inclusive nature. The Rajputs of Rajasthan eventually refused to acknowledge the Rajput identity claimed by their eastern counterparts,[75] such as the Bundelas.[76] The Rajputs claim to be Kshatriyas or descendants of Kshatriyas, but their actual status varies greatly, ranging from princely lineages to common cultivators.[77]

There are several major subdivisions of Rajputs, known as vansh or vamsha, the step below the super-division jāti[78] These vansh delineate claimed descent from various sources, and the Rajput are generally considered to be divided into three primary vansh:[79] Suryavanshi denotes descent from the solar deity Surya, Chandravanshi (Somavanshi) from the lunar deity Chandra, and Agnivanshi from the fire deity Agni. The Agnivanshi clans include Parmar, Chaulukya (Solanki), Parihar and Chauhan.[80]

Lesser-noted vansh include Udayvanshi, Rajvanshi,[81] and Rishivanshi. The histories of the various vanshs were later recorded in documents known as vamshāavalīis; André Wink counts these among the "status-legitimizing texts".[82]

Beneath the vansh division are smaller and smaller subdivisions: kul, shakh ("branch"), khamp or khanp ("twig"), and nak ("twig tip").[78] Marriages within a kul are generally disallowed (with some flexibility for kul-mates of different gotra lineages). The kul serves as the primary identity for many of the Rajput clans, and each kul is protected by a family goddess, the kuldevi. Lindsey Harlan notes that in some cases, shakhs have become powerful enough to be functionally kuls in their own right.[83]

Culture and ethos

The Rajputs were designated as a Martial Race in the period of the British Raj.[84] This was a designation created by administrators that classified each ethnic group as either "martial" or "non-martial": a "martial race" was typically considered brave and well built for fighting,[85] whilst the remainder were those whom the British believed to be unfit for battle because of their sedentary lifestyles.[86]

Rajput lifestyle

The double-edged scimitar known as the khanda was a popular weapon among the Rajputs of that era. On special occasions, a primary chief would break up a meeting of his vassal chiefs with khanda nariyal, the distribution of daggers and coconuts. Another affirmation of the Rajput's reverence for his sword was the Karga Shapna ("adoration of the sword") ritual, performed during the annual Navaratri festival, after which a Rajput is considered "free to indulge his passion for rapine and revenge".[87] The Rajput of Rajasthan also offer a sacrifice of water buffalo or goat to their family Goddess ( Kuldevta) during Navaratri.[88] The ritual requires slaying of the animal with a single stroke. In the past this ritual was considered a rite of passage for young Rajput men.[89]

Rajputs generally have adopted the custom of purdah (seclusion of women).[50]

By the late 19th century, there was a shift of focus among Rajputs from politics to a concern with kinship.[90] Many Rajputs of Rajasthan are nostalgic about their past and keenly conscious of their genealogy, emphasising a Rajput ethos that is martial in spirit, with a fierce pride in lineage and tradition.[91]

Rajput diet

Rajputs are 'by and large' non-vegetarians, eating wild boar, regular drinkers of alcohol, and also smoke and chew betel leaves.[92][93]

Rajput politics

Rajput politics refers to the role played by the Rajput community in the electoral politics of India.[95][96] In states such as Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, Uttrakhand, Jammu, Himachal Pradesh, and Gujarat, the large populations of Rajputs gives them a decisive role.[97][98][99]

Arts

The term Rajput painting refers to works of art created at the Rajput-ruled courts of Rajasthan, Central India, and the Punjab Hills. The term is also used to describe the style of these paintings, distinct from the Mughal painting style.[100]

According to Ananda Coomaraswamy, Rajput painting symbolised the divide between Muslims and Hindus during Mughal rule. The styles of Mughal and Rajput painting are oppositional in character. He characterised Rajput painting as "popular, universal and mystic".[101]

Rajput painting varied geographically, corresponding to each of the various Rajput kingdoms and regions. The Delhi area, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Central India each had its own variant.[102]

See also

References

- ↑ Singh, K.S. (General editor) (1998). People of India. Anthropological Survey of India. pp. 489, 880, 656. ISBN 9788171547661. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Cohen, Stephen Philip (2006). The idea of Pakistan (Rev. ed.). Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0815715030. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Lieven, Anatol (2011). Pakistan a hard country (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781610390231. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Folk-lore, Volume 21". 1980. p. 79. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ Roy, Ramashray (2003-01-01). Samaskaras in Indian Tradition and Culture. p. 195. ISBN 9788175411401. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ↑ Rajendra Vora (2009). Christophe Jaffrelot; Sanjay Kumar, eds. Rise of the Plebeians?: The Changing Face of the Indian Legislative Assemblies (Exploring the Political in South Asia). Routledge India. p. 217.

[In Maharashtra]The Lingayats, the Gujjars and the Rajputs are three other important castes which belong to the intermediate category. The lingayats who hail from north Karnataka are found primarily in south Maharashtra and Marthwada while Gujjars and Rajputs who migrated centuries ago from north India have settled in north Maharashtra districts.

- 1 2 Alf Hiltebeitel 1999, pp. 439-440.

- ↑ Bhrigupati Singh 2015, p. 38.

- ↑ Pradeep Barua 2005, p. 24.

- ↑ Alf Hiltebeitel 1999, pp. 440-441.

- ↑ Alf Hiltebeitel 1999, pp. 441-442.

- 1 2 Catherine B. Asher & Cynthia Talbot 2006, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 119.

- ↑ Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya 1994, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ Satish Chandra 1982, p. 92.

- 1 2 Tanuja Kothiyal 2016, p. 8.

- ↑ Richard Gabriel Fox 1971, p. 16.

- ↑ Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya 1994, p. 60.

- ↑ Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya 1994, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 120.

- 1 2 Tanuja Kothiyal 2016, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 121.

- ↑ Irfan Habib 2002, p. 90.

- ↑ David Ludden 1999, p. 4.

- ↑ Barbara N. Ramusack 2004, p. 13.

- ↑ André Wink 1990, p. 282.

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot 2015, pp. 121-122.

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 121-125.

- ↑ Tanuja Kothiyal 2016, p. 11.

- ↑ Pradeep Barua 2005, p. 25.

- ↑ Peter Jackson 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 33.

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 33-35.

- ↑ Naravane, M.S (1999). The Rajputs of Rajputana: A Glimpse of Medieval Rajasthan. APH Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 978-81-7648-118-2.

- ↑ Chandra, Satish (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206–1526) - Part One. Har-Anand Publications. p. 224. ISBN 978-81-241-1064-5.

- ↑ Sarda, Har Bilas (1970). Maharana Sāngā, the Hindupat: The Last Great Leader of the Rajput Race. Kumar Bros. p. 1.

- ↑ Pradeep Barua 2005, pp. 33-34.

- ↑ Farooqui, Amar (2007). "The Subjugation of the Sindia State". In Ernst, Waltraud; Pati, Biswamoy. India's Princely States: People, Princes and Colonialism. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-134-11988-2.

- ↑ Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-0-521-25119-8.

- ↑ Bhadani, B. L. (1992). "The Profile of Akbar in Contemporary Literature". Social Scientist. 20 (9/10): 48–53. JSTOR 3517716. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 272–273. ISBN 978-81-269-0123-4.

- ↑ Dirk H. A. Kolff 2002, p. 132.

- ↑ Smith, Bonnie G. (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press,. p. 656. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- ↑ Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press,. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2.

- ↑ Lal, Ruby (2005). Domesticity and Power in the Early Mughal World. Cambridge University Press,. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-521-85022-3.

- ↑ Vivekanandan, Jayashree (2012). Interrogating International Relations: India's Strategic Practice and the Return of History War and International Politics in South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-70385-0.

- ↑ Hansen, Waldemar (1972). The peacock throne : the drama of Mogul India (1. Indian ed., repr. ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 12, 34. ISBN 978-81-208-0225-4.

- ↑ Barbara N. Ramusack 2004, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Bayly, Susan (2000). Caste, society and politics in India from the eighteenth century to the modern age (1. Indian ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780521798426.

- 1 2 3 "Rajput". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ Naravane, M. S. (1999). The Rajputs of Rajputana: A Glimpse of Medieval Rajasthan. APH Publishing. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-81-7648-118-2.

- ↑ Sir Jadunath Sarkar (1994). A History of Jaipur 1503–1938. Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- ↑ Naravane, M.S (1999). The Rajputs of Rajputana: A Glimpse of Medieval Rajasthan. APH Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-7648-118-2.

- ↑ Tanuja Kothiyal 2016, pp. 9-10.

- ↑ Srivastava, Vijai Shankar (1981). "The story of archaeological, historical and antiquarian researches in Rajasthan before independence". In Prakash, Satya; Śrivastava, Vijai Shankar. Cultural contours of India: Dr. Satya Prakash felicitation volume. Abhinav Publications. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-391-02358-1. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ↑ Meister, Michael W. (1981). "Forest and Cave: Temples at Candrabhāgā and Kansuāñ". Archives of Asian Art. 34: 56–73. JSTOR 20111117. (subscription required)

- ↑ Freitag, Jason (2009). Serving empire, serving nation: James Tod and the Rajputs of Rajasthan. BRILL. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-90-04-17594-5.

- ↑ "Derawar Fort – Living to tell the tale". DAWN. Karachi. 20 June 2011.

- ↑ Bates, Crispin (1995). "Race, Caste and Tribe in Central India: the early origins of Indian anthropometry". In Robb, Peter. The Concept of Race in South Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-19-563767-0. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ↑ Bingley, A. H. (1986) [1899]. Handbook on Rajputs. Asian Educational Services. p. 20. ISBN 978-81-206-0204-5.

- ↑ Markovits, Claude, ed. (2002) [First published 1994 as Histoire de l'Inde Moderne]. A History of Modern India, 1480–1950 (2nd ed.). London: Anthem Press. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-84331-004-4.

The twenty-two princely states that were amalgamated in 1949 to form a political entity called Rajasthan ...

- ↑ Gerald James Larson (2001). Religion and Personal Law in Secular India: A Call to Judgment. Indiana University Press. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-0-253-21480-5. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Bishnu Raj Upreti (2002). Management of Social and Natural Resource Conflict in Nepal. Pinnacle Technology. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-61820-370-0. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ "Dogra dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ "The Constitution (26 Amendment) Act, 1971", indiacode.nic.in, Government of India, 1971, archived from the original on 6 December 2011, retrieved 30 October 2014

- ↑ "Central List of OBCs - State : Karnataka".

- ↑ "12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010" (PDF).

- ↑ A.Prasad (1997). Reservational Justice to Other Backward Classes (Obcs): Theoretical and Practical Issues. Deep and Deep Publications. p. 69.

(continued list of OBC classes) 7.Rajput 120.Karnataka Rajput

- ↑ Basu, Pratyusha (2009). Villages, Women, and the Success of Dairy Cooperatives in India: Making Place for Rural Development. Cambria Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-60497-625-0.

- ↑ "Rajput youths rally for reservations - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ Mudgal, Vipul (22 February 2016). "The Absurdity of Jat Reservation". The Wire. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ "Rajputs demanding reservation threaten to disrupt chintan shivir". The Hindu. 16 January 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ "After Jats, Rajputs of western UP want reservation in govt posts". Hindustan Times. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ↑ Ayan Shome 2014, p. 196.

- ↑ Catherine B. Asher & Cynthia Talbot 2006, p. 99 (Para 3): "...Rajput did not originally indicate a hereditary status but rather an occupational one: that is, it was used in reference to men from diverse ethnic and geographical backgrounds, who fought on horseback. In Rajasthan and its vicinity, the word Rajput came to have a more restricted and aristocratic meaning, as exclusive networks of warriors related by patrilineal descent and intermarriage became dominant in the fifteenth century. The Rajputs of Rajasthan eventually refused to acknowledge the Rajput identity of the warriors who lived farther to the east and retained the fluid and inclusive nature of their communities far longer than did the warriors of Rajasthan."

- ↑ Cynthia Talbot 2015, p. 120 (Para 4): "Kolff's provocative thesis certainly applies to more peripheral groups like the Bundelas of Cenral India, whose claims to be Rajput were ignored by the Rajput clans of Mughal-era Rajasthan, and to other such lower-status martial communities."

- ↑ "Rajput". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- 1 2 Shail Mayaram 2013, p. 269.

- ↑ Rolf Lunheim (1993). Desert people: caste and community—a Rajasthani village. University of Trondheim & Norsk Hydro AS. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Maya Unnithan-Kumar (1997). Identity, Gender, and Poverty: New Perspectives on Caste and Tribe in Rajasthan. Berghahn Books. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-57181-918-5. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Makhan Jha (1 January 1997). Anthropology of Ancient Hindu Kingdoms: A Study in Civilizational Perspective. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-81-7533-034-4. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7Th-11th Centuries. BRILL. pp. 282–. ISBN 978-0-391-04173-8. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ↑ Lindsey Harlan 1992, p. 31.

- ↑ Mazumder, Rajit K. The Indian Army and the Making of Punjab. pp. 99, 105.

- ↑ Rand, Gavin (March 2006). "Martial Races and Imperial Subjects: Violence and Governance in Colonial India 1857–1914". European Review of History. 13 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1080/13507480600586726.

- ↑ Streets, Heather (2004). Martial Races: The military, race and masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857–1914. Manchester University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7190-6962-8. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Narasimhan, Sakuntala (1992). Sati: widow burning in India (Reprinted ed.). Doubleday. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-385-42317-5.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel, Alf; Erndl, Kathleen M. (2000). Is the Goddess a Feminist?: The Politics of South Asian Goddesses. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8147-3619-7.

- ↑ Lindsey Harlan 1992, p. 88.

- ↑ Kasturi, Malavika (2002). Embattled Identities Rajput Lineages. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-565787-6.

- ↑ Lindsey Harlan 1992, p. 27.

- ↑ Lindsey Harlan (1992). Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives. University of California Press. p. 158. ISBN 9780520073395.

Many women do not like their husbands to drink much alcohol; they consider alcoholism a problem in their community particularly because Rajput drinking is sanctioned by tradition.

- ↑ Mahesh Rangarajan, K; Sivaramakrishnan, eds. (2014-11-06). Shifting Ground: People, Animals, and Mobility in India's Environmental History. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780199089376.

The British defined Rajputs as a group in part by their affinity for wild pork.

- ↑ Rajput procession, Encyclopædia Britannica Archived 9 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Caste politics in North, West and South India before Mandal : The low caste movements between sanskritisation and ethnicisation" (PDF). Kellogg.nd.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ↑ Dipankar Gupta. "The caste bogey in election analysis". The Hindu. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Changing Electoral Politics in Delhi". google.co.in. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Elections in India: The vote-bank theory has run its course". Asiancorrespondent.com. 2012-02-07. Retrieved 2015-03-18.

- ↑ "Rajasthan polls: It's caste politics all the way". The Times of India. 13 October 2013.

- ↑ Karine Schomer 1994, p. 338.

- ↑ Saleema Waraich (2012). "Competing and complementary visions of the court of the Great Mogor". In Dana Leibsohn; Jeanette Favrot Peterson. Seeing Across Cultures in the Early Modern World. Ashgate. p. 88. ISBN 9781409411895.

- ↑ Leibsohn, Dana; Peterson, Jeanette (2012). Seeing Across Cultures in the Early Modern World. Ashgate Publishing. p. 3.

Bibliography

- Alf Hiltebeitel (1999). Rethinking India's Oral and Classical Epics: Draupadi among Rajputs, Muslims, and Dalits. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-34055-5.

- André Wink (1990). Al- Hind: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest. 1. BRILL. p. 269. ISBN 9789004095090.

- Ayan Shome (2014). Dialogue & Daggers: Notion of Authority and Legitimacy in the Early Delhi Sultanate (1192 C.E. – 1316 C.E.). Vij Books. ISBN 978-93-84318-46-8.

- Barbara N. Ramusack (2004). The Indian Princes and their States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139449083.

- Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (1994). "Origin of the Rajputs: The Political, Economic and Social Processes in Early Medieval Rajasthan". The Making of Early Medieval India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195634150.

- Bhrigupati Singh (2015). Poverty and the Quest for Life. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-19468-4.

- Catherine B. Asher; Cynthia Talbot (2006). India Before Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7.

- Cynthia Talbot (2015). The Last Hindu Emperor: Prithviraj Cauhan and the Indian Past, 1200–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118560.

- David Ludden (1999). An Agrarian History of South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-36424-9.

- Dirk H. A. Kolff (2002). Naukar, Rajput, and Sepoy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52305-9.

- Irfan Habib (2002). Essays in Indian History. Anthem Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-84331-061-7.

- Karine Schomer (1994). Idea of Rajasthan: Constructions. South Asia Publications. ISBN 978-0-945921-25-7.

- Lindsey Harlan (1992). Religion and Rajput Women: The Ethic of Protection in Contemporary Narratives. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07339-5.

- Pradeep Barua (2005). The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1344-9.

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.

- Richard Gabriel Fox (1971). Kin, Clan, Raja, and Rule: Statehinterland Relations in Preindustrial India. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520018075.

- Satish Chandra (1982). Medieval India: Society, the Jagirdari Crisis, and the Village. Macmillan.

- Shail Mayaram (2013). Against History, Against State: Counterperspectives from the Margins. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52951-8.

- Tanuja Kothiyal (2016). Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107080317.

External links

![]()

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rajput |