European Council

Emblem | |

| Formation |

1961 (informally) 2009 (formally) |

|---|---|

| Type | EU collective presidency |

| Location | |

| Donald Tusk | |

| Website | European Council |

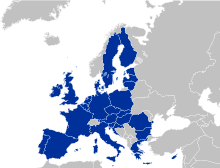

The European Council, charged with defining the European Union's (EU) overall political direction and priorities, is the institution of the EU that comprises the heads of state or government of the member states, along with the President of the European Council and the President of the European Commission. The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy also takes part in its meetings.[1] Established as an informal summit in 1975, the European Council was formalised as an institution in 2009 upon the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon. Its current President is Donald Tusk, former Prime Minister of Poland.

Scope

While the European Council has no formal legislative power, it is a strategic (and crisis-solving) body that provides the union with general political directions and priorities, and acts as a collective presidency. The European Commission remains the sole initiator of legislation, but the European Council is able to provide an impetus to guide legislative policy.[2][3]

The meetings of the European Council, still commonly referred to as EU summits, are chaired by its president and take place at least twice every six months;[1] usually in the Europa building in Brussels.[4][5] Decisions of the European Council are taken by consensus, except where the Treaties provide otherwise.[6]

History

The European Council officially gained the status of an EU institution after the Treaty of Lisbon in 2007, distinct from the Council of the European Union (Council of Ministers). Before that, the first summits of EU heads of state or government were held in February and July 1961 (in Paris and Bonn respectively). They were informal summits of the leaders of the European Community, and were started due to then-French President Charles de Gaulle's resentment at the domination of supranational institutions (notably the European Commission) over the integration process, but petered out. The first influential summit held, after the departure of de Gaulle, was the Hague summit of 1969, which reached an agreement on the admittance of the United Kingdom into the Community and initiated foreign policy cooperation (the European Political Cooperation) taking integration beyond economics.[1][7]

The summits were only formalised in the period between 1974 and 1988. At the December summit in Paris in 1974, following a proposal from then-French president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, it was agreed that more high level, political input was needed following the "empty chair crisis" and economic problems.[8] The inaugural European Council, as it became known, was held in Dublin on 10 and 11 March 1975 during Ireland's first Presidency of the Council of Ministers. In 1987, it was included in the treaties for the first time (the Single European Act) and had a defined role for the first time in the Maastricht Treaty. At first only a minimum of two meetings per year were required, which resulted in an average of three meetings per year being held for the 1975-1995 period. Since 1996, the number of meetings were required to be minimum four per year. For the latest 2008-2014 period, this minimum was well exceeded, by an average of seven meetings being held per year. The seat of the Council was formalised in 2002, basing it in Brussels. Three types of European Councils exist: Informal, Scheduled and Extraordinary. While the informal meetings are also scheduled 1½ years in advance, they differ from the scheduled ordinary meetings by not ending with official Council conclusions, as they instead end by more broad political Statements on some cherry picked policy matters. The extraordinary meetings always end with official Council conclusions - but differs from the scheduled meetings by not being scheduled more than a year in advance, as for example in 2001 when the European Council gathered to lead the European Union's response to the 11 September attacks.[1][7]

.jpg)

Some meetings of the European Council—and, before the Council was formalised, meetings of the heads of government—are seen by some as turning points in the history of the European Union. For example:[1]

- 1969, The Hague: Foreign policy and enlargement.

- 1974, Paris: Creation of the Council.

- 1985, Milan: Initiate IGC leading to the Single European Act.

- 1991, Maastricht: Agreement on the Maastricht Treaty.

- 1992, Edinburgh: Agreement (by treaty provision) to retain at Strasbourg the plenary seat of the European Parliament.

- 1993, Copenhagen: Leading to the definition of the Copenhagen Criteria.

- 1997, Amsterdam: Agreement on the Amsterdam Treaty.

- 1998, Brussels: Selected member states to adopt the euro.

- 1999; Cologne: Declaration on military forces.[9]

- 1999, Tampere: Institutional reform

- 2000, Lisbon: Lisbon Strategy

- 2002, Copenhagen: Agreement for May 2004 enlargement.

- 2007, Lisbon: Agreement on the Lisbon Treaty.

- 2009, Brussels: Appointment of first president and merged High Representative.

- 2010, European Financial Stability Facility

As such, the European Council had already existed before it gained the status as an institution of the European Union with the entering into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, but even after it had been mentioned in the treaties (since the Single European Act) it could only take political decisions, not formal legal acts. However, when necessary, the Heads of State or Government could also meet as the Council of Ministers and take formal decisions in that role. Sometimes, this was even compulsory, e.g. Article 214(2) of the Treaty establishing the European Community provided (before it was amended by the Treaty of Lisbon) that ‘the Council, meeting in the composition of Heads of State or Government and acting by a qualified majority, shall nominate the person it intends to appoint as President of the Commission’ (emphasis added); the same rule applied in some monetary policy provisions introduced by the Maastricht Treaty (e.g. Article 109j TEC). In that case, what was politically part of a European Council meeting was legally a meeting of the Council of Ministers. When the European Council, already introduced into the treaties by the Single European Act, became an institution by virtue of the Treaty of Lisbon, this was no longer necessary, and the "Council [of the European Union] meeting in the composition of the Heads of State or Government", was replaced in these instances by the European Council now taking formal legally binding decisions in these cases (Article 15 of the Treaty on European Union).[10]

The Treaty of Lisbon made the European Council a formal institution distinct from the (ordinary) Council of the EU, and created the present longer term and full-time presidency. As an outgrowth of the Council of the EU, the European Council had previously followed the same Presidency, rotating between each member state. While the Council of the EU retains that system, the European Council established, with no change in powers, a system of appointing an individual (without them being a national leader) for a two-and-a-half-year term - which can be renewed for the same person only once.[11] Following the ratification of the treaty in December 2009, the European Council elected the then-Prime Minister of Belgium Herman Van Rompuy as its first permanent president (resigning from Belgian Prime Minister).[12]

Powers and functions

The European Council is an official institution of the EU, mentioned by the Lisbon Treaty as a body which "shall provide the Union with the necessary impetus for its development". Essentially it defines the EU's policy agenda and has thus been considered to be the motor of European integration.[1] Beyond the need to provide "impetus", the Council has developed further roles: to "settle issues outstanding from discussions at a lower level", to lead in foreign policy — acting externally as a "collective Head of State", "formal ratification of important documents" and "involvement in the negotiation of the treaty changes".[4][7]

Since the institution is composed of national leaders, it gathers the executive power of the member states and has thus a great influence in high-profile policy areas as for example foreign policy. It also exercises powers of appointment, such as appointment of its own President, the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, and the President of the European Central Bank. It proposes, to the European Parliament, a candidate for President of the European Commission. Moreover, the European Council influences police and justice planning, the composition of the Commission, matters relating to the organisation of the rotating Council presidency, the suspension of membership rights, and changing the voting systems through the Passerelle Clause. Although the European Council has no direct legislative power, under the "emergency brake" procedure, a state outvoted in the Council of Ministers may refer contentious legislation to the European Council. However, the state may still be outvoted in the European Council.[11][13][14] Hence with powers over the supranational executive of the EU, in addition to its other powers, the European Council has been described by some as the Union's "supreme political authority".[4][7][11][15]

Composition

The European Council consists of the heads of state or government of the member states, alongside its own President and the Commission President (both non-voting). The meetings used to be regularly attended by the national foreign minister as well, and the Commission President likewise accompanied by another member of the Commission. However, since the Treaty of Lisbon, this has been discontinued, as the size of the body had become somewhat large following successive accessions of new Member States to the Union.[1][4]

Meetings can also include other invitees, such as the President of the European Central Bank, as required. The Secretary-General of the Council attends, and is responsible for organisational matters, including minutes. The President of the European Parliament also attends to give an opening speech outlining the European Parliament's position before talks begin.[1][4]

Additionally, the negotiations involve a large number of other people working behind the scenes. Most of those people, however, are not allowed to the conference room, except for two delegates per state to relay messages. At the push of a button members can also call for advice from a Permanent Representative via the "Antici Group" in an adjacent room. The group is composed of diplomats and assistants who convey information and requests. Interpreters are also required for meetings as members are permitted to speak in their own languages.[1]

As the composition is not precisely defined, some states which have a considerable division of executive power can find it difficult to decide who should attend the meetings. While an MEP, Alexander Stubb argued that there was no need for the President of Finland to attend Council meetings with or instead of the Prime Minister of Finland (who was head of European foreign policy).[16] In 2008, having become Finnish Foreign Minister, Stubb was forced out of the Finnish delegation to the emergency council meeting on the Georgian crisis because the President wanted to attend the high-profile summit as well as the Prime Minister (only two people from each country could attend the meetings). This was despite Stubb being head of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe at the time which was heavily involved in the crisis. Problems also occurred in Poland where the President of Poland and the Prime Minister of Poland were of different parties and had a different foreign policy response to the crisis.[17] A similar situation arose in Romania between President Traian Băsescu and Prime Minister Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu in 2007–2008 and again in 2012 with Prime Minister Victor Ponta, who both opposed the president.

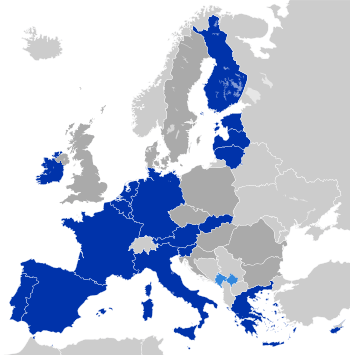

Eurozone summits

A number of ad hoc meetings of Heads of State or Government of the Euro area countries were held in 2010 and 2011 to discuss the Sovereign Debt crisis. It was agreed in October 2011 that they should meet regularly twice a year (with extra meetings if needed). This will normally be at the end of a European Council meeting and according to the same format (chaired by the President of the European Council and including the President of the Commission), but usually restricted to the (currently 19) Heads of State or Government of countries whose currency is the euro.

President

The President of the European Council is elected by the European Council by a qualified majority for a once-renewable term of two and a half years.[18] The President must report to the European Parliament after each European Council meeting.[4][15]

The post was created by the Treaty of Lisbon and was subject to a debate over its exact role. Prior to Lisbon, the Presidency rotated in accordance with the Presidency of the Council of the European Union.[4][15] The role of that President-in-Office was in no sense (other than protocol) equivalent to an office of a head of state, merely a primus inter pares (first among equals) role among other European heads of government. The President-in-Office was primarily responsible for preparing and chairing the Council meetings, and had no executive powers other than the task of representing the Union externally. Now the leader of the Council Presidency country can still act as president when the permanent president is absent.

Members

European People's Party (8 + 2 non-voting from the EU institutions) Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (7) Party of European Socialists (5) Independent (5) Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe (2) Party of the European Left (1) Presidency of the Council of the EU

European Council | ||||||||

| Member state | Representative | Member state | Representative | Member state | Representative | |||

– European Union (non-voting) – 1 December 2014 Prime Minister of Poland 2007–2014 – Election 2014, 2017 Next by 2019 |

_(cropped).jpg) President of the European Council Donald Tusk (EPP – PO) |

– European Union (non-voting) – Member since 1 November 2014 Prime Minister of Luxembourg 1995–2013 – Election 2014 Next in 2019 |

President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker (EPP – CSV) |

– Republic of Austria (1.71% of population)[a 1] – Member since 18 December 2017 – Election 2017 Next by 2022 |

Federal Chancellor Sebastian Kurz (EPP – ÖVP) | |||

– Kingdom of Belgium (2.21% of population) – Member since 11 October 2014 – Election 2014 Next by 2019 |

_01_(cropped).jpg) Prime Minister Charles Michel (ALDE – MR) |

– Republic of Bulgaria (1.39% of population) – Member since 4 May 2017 Prime Minister 2009–2013; 2014–2017 – Election 2009, 2014, 2017 Next by 2021 |

Minister-President Boyko Borisov (EPP – GERB) |

– Republic of Croatia (0.81% of population) – Member since 19 October 2016 – Election 2016 Next by 2020 |

_(cropped).jpg) President of the Government Andrej Plenković (EPP – HDZ) | |||

– Republic of Cyprus (0.17% of population) – Member since 28 February 2013 – Election 2013, 2018 Next by 2023 |

President Nicos Anastasiades (EPP – DISY) |

– Czech Republic (2.04% of population) – Member since 6 December 2017 – Election 2017 Next by 2021 |

Chairman of the Government Andrej Babiš (ALDE – ANO) |

– Kingdom of Denmark (1.12% of population) – Member since 28 June 2015 Prime Minister 2009–2011 – Election 2015 Next by 2019 |

_(cropped).jpg) Minister of State Lars Løkke Rasmussen (ALDE – V) | |||

– Republic of Estonia (0.26% of population) – Member since 23 November 2016 – Next by 2019 |

.jpg) Head Minister Jüri Ratas (ALDE – EK) |

– Republic of Finland (1.07% of population) – Member since 29 May 2015 – Election 2015 Next by 2019 |

.jpg) Minister of State Juha Sipilä (ALDE – C) |

– French Republic (13.09% of population) – Member since 14 May 2017 – Election 2017 Next by 2022 |

President Emmanuel Macron (Ind. – REM) | |||

– Federal Republic of Germany (16.10% of population) – Member since 22 November 2005 – Election 2005, 2009, 2013, 2017 Next by 2021 |

Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel (EPP – CDU) |

– Hellenic Republic (2.10% of population) – Member since 25 September 2015 Prime Minister 2015 – Election 2015, 2015 Next by 2019 |

President of the Government Alexis Tsipras (PEL – Syriza) |

– Hungary (1.91% of population) – Member since 29 May 2010 Prime Minister 1998–2002 – Election 1998, 2010, 2014, 2018 Next by 2022 |

Minister-President Viktor Orbán (EPP – Fidesz) | |||

– Ireland (0.93% of population) – Member since 14 June 2017 – Next by 2022 |

_(cropped).jpg) Taoiseach Leo Varadkar (EPP – FG) |

– Italian Republic (11.95% of population) – Member since 1 June 2018 – Election 2018 Next by 2022 |

.jpg) President of the Council of Ministers Giuseppe Conte (Ind. – Ind.) |

– Republic of Latvia (0.38% of population) – Member since 11 February 2016 – Election 2018 Next by 2022 |

.jpg) Minister-President Māris Kučinskis (Ind. – LP) | |||

– Republic of Lithuania (0.56% of population) – Member since 12 July 2009 – Election 2009, 2014 Next by 2019 |

President Dalia Grybauskaitė (Ind. – Ind.) |

– Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (0.12% of population) – Member since 4 December 2013 – Election 2013, 2018 Next by 2023 |

_CROP_BETTEL.jpg) Prime Minister Xavier Bettel (ALDE – DP) |

– Republic of Malta (0.09% of population) – Member since 11 March 2013 – Election 2013, 2017 Next by 2022 |

Prime Minister Joseph Muscat (PES – PL) | |||

– Kingdom of the Netherlands (3.36% of population) – Member since 14 October 2010 – Election 2010, 2012, 2017 Next by 2021 |

_(cropped).jpg) Minister-President Mark Rutte (ALDE – VVD) |

– Republic of Poland (7.41% of population) – Member since 11 December 2017 – Next by 2019 |

.jpg) President of the Council of Ministers Mateusz Morawiecki (ACRE – PiS) |

– Portuguese Republic (2.01% of population) – Member since 26 November 2015 – Next by 2019 |

Prime Minister António Costa (PES – PS) | |||

– Romania (3.83% of population) – Member since 21 December 2014 – Election 2014 Next by 2019 |

President Klaus Iohannis (EPP[a 2] – Ind.[a 3]) |

– Slovak Republic (1.06% of population) – Member since 22 March 2018 – Next by 2020 |

_Pellegrini.jpg) Chairman of the Government Peter Pellegrini (PES – Smer–SD) |

– Republic of Slovenia (0.40% of population) – Member since 13 September 2018 – Election 2018 Next by 2022 |

President of the Government Marjan Šarec (Ind. – LMŠ) | |||

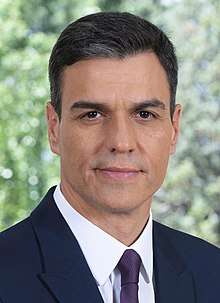

– Kingdom of Spain (9.08% of population) – Member since 2 June 2018 – Next by 2020 |

President of the Government Pedro Sánchez (PES – PSOE) |

– Kingdom of Sweden (1.97% of population) – Member since 3 October 2014 – Election 2014, 2018 Next by 2022 |

_(cropped).jpg) Minister of the State Stefan Löfven (PES – SAP) |

– United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (12.85% of population) – Member since 13 July 2016 – Election 2015, 2017[a 4] |

| |||

- Notes

- ↑ Used in the calculation of the qualified majority voting. The share of the total population is based on the decision of the Council of the European Union on Member States populations for 2018

- ↑ Considered an EPP member according to its official webpage.

- ↑ Previously leader of the National Liberal Party (PNL) and supported by them during his election campaign, Iohannis is officially unaffiliated during his presidency according to the Constitution.

- ↑ Under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, the next general election is scheduled for 2022. The United Kingdom is expected to have left the European Union prior to this date, unless an early election is called or the negotiation period is extended.

Political parties

.png)

Does not account for coalitions. Key to colours is as follows;

Almost all members of the European Council are members of a political party at national level, and most of these are members of a European-level political party. These frequently hold pre-meetings of their European Council members, prior to its meetings. However, the European Council is composed to represent the EU's states rather than political parties and decisions are generally made on these lines, though ideological alignment can colour their political agreements and their choice of appointments (such as their president).

The table below outlines the number of leaders affiliated to each party and their total voting weight. The map to the right indicates the alignment of each individual country.

| Party | Number of seats | Share of population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| European People's Party | 8 | 26.85% | |

| Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party | 7 | 10.19% | |

| Party of European Socialists | 5 | 14.21% | |

| Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe | 2 | 20.26% | |

| Party of the European Left | 1 | 2.10% | |

| Independent | 5 | 26.38% | |

| Total | 28 | 100% | |

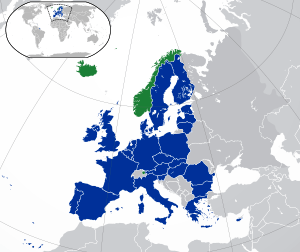

Seat and meetings

The European Council is required by Article 15.3 TEU to meet at least twice every six months, but convenes more frequently in practice.[19][20] Despite efforts to contain business, meetings typically last for at least two days, and run long into the night.[20]

Until 2002, the venue for European Council summits was the member state that held the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union. However, European leaders agreed during ratification of the Nice Treaty to forego this arrangement at such a time as the total membership of the European Union surpassed 18 member states.[21] An advanced implementation of this agreement occurred in 2002, with certain states agreeing to waive their right to host meetings, favouring Brussels as the location.[22] Following the growth of the EU to 25 member states, with the 2004 enlargement, all subsequent official summits of the European Council have been in Brussels, with the exception of punctuated ad hoc meetings, such as the 2017 informal European Council in Malta.[23] The logistical, environmental, financial and security arrangements of hosting large summits are usually cited as the primary factors in the decision by EU leaders to move towards a permanent seat for the European Council.[7] Additionally, some scholars argue that the move, when coupled with the formalisation of the European Council in the Lisbon Treaty, represents an institutionalisation of an ad hoc EU organ that had its origins in Luxembourg compromise, with national leaders reasserting their dominance as the EU's "supreme political authority".[7]

Originally, both the European Council and the Council of the European Union utilised the Justus Lipsius building as their Brussels venue. In order to make room for additional meeting space a number of renovations were made, including the conversion of an underground carpark into additional press briefing rooms.[24] However, in 2004 leaders decided the logistical problems created by the outdated facilities warranted the construction of a new purpose built seat able to cope with the nearly 6,000 meetings, working groups, and summits per year.[5] This resulted in the Europa building, which opened its doors in 2017. The focal point of the new building, the distinctive multi-storey "lantern-shaped" structure in which the main meeting room is located, is utilised in both the European Council's and Council of the European Union's official logos.[25]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union" (PDF).

- ↑ Art. 13 et seq of the Treaty on European Union

- ↑ Gilbert, Mark (2003). Surpassing Realism – The Politics of European Integration since 1945 (page 219: Making Sense of Maastricht). Rowman & Littlefield. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "EUROPA – The European Council: Presidency Conclusions". European Commission. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- 1 2 "EUROPA : Home of the European Council and the Council of the EU - Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Art. 15(4) of the Treaty on European Union

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stark, Christine. "Evolution of the European Council: The implications of a permanent seat" (PDF). Dragoman.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ↑ On the economic problems, see Imbrogno, Anthony (2016). "The Founding of the European Council: economic reform and the mechanism of continuous negotiation". Journal of European Integration 38 no.6, pp.719-736. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07036337.2016.1188925

- ↑ "EU Security Policy & the role of the European Commission". European Commission. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2007.

- ↑ Wikisource: Article 2(3)(e), Treaty of Lisbon

- 1 2 3 "The Union's institutions: The European Council". Europa (web portal). 21 February 2001. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ↑ "BBC News — Belgian PM Van Rompuy is named as new EU president". 20 November 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ↑ Peers, Steve (2 August 2007). "EU Reform Treaty Analysis no. 2.2: Foreign policy provisions of the revised text of the Treaty on the European Union (TEU)" (PDF). Statewatch. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ↑ Peers, Steve (2 August 2007). "EU Reform Treaty analysis 1: JHA provisions" (PDF). Statewatch. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- 1 2 3 "How does the EU work". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ↑ "Finnish Conservatives name Stubb foreign minister". new Room Finland. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- ↑ Phillips, Leigh (29 August 2008). "Spats over who gets to go to EU summit break out in Poland, Finland". EU Observer. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

- ↑ "European Council: The President's role". Retrieved 21 March 2015.

The President the European Council is elected by the European Council by a qualified majority. He is elected for a 2.5 year term, which is renewable once.

- ↑ Consolidated version of the Treaty on European Union.

- 1 2 "The European Council – the who, what, where, how and why – UK in a changing Europe". ukandeu.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ Treaty of Nice.

- ↑ "Permanent seat for the European Council could change the EU's nature". EURACTIV.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "Informal meeting of EU heads of state or government, Malta, 03/02/2017 - Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "Why PMs won't miss going to EU Council summits". Sky News. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ↑ "New HQ, new logo". POLITICO. 2014-01-15. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

Further reading

- Wessels, Wolfgang (2016). The European Council. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333587461.

External links

- Official website

- Archive of European Integration – Summit Guide

- European Council Collection of documents - CVCE

- Reflection Group established by the European Council