Romania and the euro

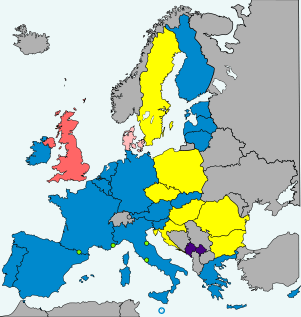

- European Union (EU) member states

- Non-EU member states

Romania is required by its EU accession agreement to replace the current national currency, the Romanian leu, with the euro, as soon as Romania fulfills all of the six nominal euro convergence criteria. The leu is not yet part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II), of which minimum two years of stable membership is one of the six nominal convergence criteria to comply with to qualify for euro adoption. The current Romanian government in addition established a self-imposed criteria to reach a certain level of "real convergence", as a steering anchor to decide the appropriate target year for ERM II-membership and euro adoption. As of March 2018, the scheduled date for euro adoption in Romania is 2024, according to Liviu Dragnea, head of the ruling Party of Social Democrats.[1]

History

To simplify future adjustments to ATMs after the adoption of the euro, when the Romanian new leu replaced the old leu in 2005 (at 10,000 old lei to 1 new leu) the new banknotes were the same physical dimensions as euro banknotes, except the 200 lei note, which had no euro size correspondent, and the 500 lei note, which was the same dimension as the €200 note.[2]

In May 2006, it was announced that the Romanian government planned to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM), a prerequisite for euro adoption, only after 2012.[3][4] The president of the ECB said in June 2007, that "Romania has a lot of homework to do ... over a number of years" before joining ERM II.[5] The Romanian government announced in December 2009, that they officially planned to join the eurozone by 1 January 2015.[6][7] In April 2011, the Romanian government announced it would strive to comply with the first four convergence criteria by 2013, but would not be ready to join the ERM II before 2013–2014.[8]

EIU analysts suggested in May 2012, that 2016-2017 would be the earliest realistic dates for Romania's adoption of the euro.[9] However, in October 2012, Valentin Lazea, the NBR chief economist, said that "the adherence of Romania to euro currency in 2015 is difficult for Romania". The governor of the National Bank of Romania confirmed in November 2012, that Romania would not meet its previous target of joining the eurozone in 2015. He mentioned that it had been a financial benefit for Romania to not be a part of the euro area during the European debt-crisis, but that the country in the years ahead would strive to comply with all the convergence criteria.[10] Concerns about its workforce productivity were also been cited for the delay.[11]

In April 2013, Romania submitted their annual Convergence Programme to the European Commission, which for the first time did not specify a target date for euro adoption.[12][13] Then Prime Minister Victor Ponta stated that "eurozone entry remains a fundamental objective for Romania but we can't enter poorly prepared", and that 2020 was a more realistic target.[13] In April 2013, the National Bank of Romania submitted draft amendments to the Romanian Constitution to the European Central Bank (ECB) for review. The amendments would make the NBR's statue an organic law to ensure "institutional and functional stability", and would allow for the "transfer of NBR tasks to the ECB and the introduction of the euro as legal tender" using organic law.[14] In 2014, Romania's Convergence Report set a target date of 1 January 2019 for euro adoption.[15][16]

According to the Erste Group Bank, it would be very difficult for Romania to meet this 2019 target, not in regards of complying with the five nominal convergence criteria values, but in regards of reaching some appropriate levels of real convergence (i.e. raising the GDP per capita from 50% to a level above 60% of the EU average) ahead of the euro adoption.[17] The Romanian Central Bank governor, Mugur Isărescu, admitted the target was ambitious, but obtainable if the political parties passed a legal roadmap for the required reforms to be implemented, and clarified this roadmap should lead to Romania entering ERM II only on 1 JanUARY 2017 - so that the euro could be adopted after two years of ERM II membership on 1 January 2019.[18] In April 2015, Isărescu stated that the technical requirement for adoption of the euro 1 January 2019 would imply joining ERM II at the latest in the first half of 2016. Ahead of ERM II entry, Isărescu argued, Romania needs to conduct monetary adjustments in form of finalizing the process of bringing minimum reserve requirement ratios in line with eurozone levels (a process envisaged to last between 1 and 1 1⁄2 years) and to complete major economic policy adjustments: removing the sources of repressed inflation (i.e. completion of the energy market deregulation); removing sources of quasi-fiscal deficits (by restructuring loss-making state-owned enterprises); and removing other sources of future budgetary pressures (i.e. the unavoidable expenditures to modernise road infrastructure).[19] Romania's Prime Minister Victor Ponta said in June 2015 that he was open to the idea of holding a referendum on euro adoption.[20]

By April 2015, the Romanian government concluded it was still on track to attain its target for euro adoption in 2019, both in regards of ensuring full compliance with all nominal convergence criteria and in regards of ensuring a prior satisfying degree of "real convergence". The Romanian target for "real convergence" ahead of euro adoption, is for its GDP per capita (in purchasing power standards) to be above 60% of the same average figure for the entire European Union, and according to the latest outlook, this relative figure was now forecast to reach 65% in 2018 and 71% in 2020,[21] after having risen at the same pace from 29% in 2002 to 54% in 2014.[22] Finally, the Romanian government also expressed its commitment fully to join all pillars of the Banking Union, as soon as possible.[21] However, in September 2015 Romania's central bank governor Mugur Isarescu said that the 2019 target was no longer realistic.[23] The new target date was initially the year 2022, as Teodor Meleșcanu, the foreign minister of Romania declared on 28 August 2017 that, as they "meet all formal requirements", Romania "could join the currency union even tomorrow". However, he thought Romania "will adopt the euro in five years, in 2022".[24] In March 2018, members of the ruling PSD voted at an extraordinary congress to back a 2024 target date to adopt the euro currency.

Status

The Maastricht Treaty originally required that all members of the European Union join the euro once certain economic criteria are met. As of May 2018, Romania meets 4 of the 7 criteria.

| Convergence criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment month | Country | HICP inflation rate[25][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[26] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[27][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

| Budget deficit to GDP[28] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[29] | ERM II member[30] | Change in rate[31][32][nb 3] | |||||

| 2012 ECB Report[nb 4] | Reference values | Max. 3.1%[nb 5] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

None open (as of 31 March 2012) | Min. 2 years (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2011) |

Max. 5.80%[nb 7] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Yes[33][34] (as of 31 Mar 2012) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2011)[35] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2011)[35] | |||||||

| 4.6% | Open | No | -0.6% | 7.25% | No | |||

| 5.2% | 33.3% | |||||||

| 2013 ECB Report[nb 8] | Reference values | Max. 2.7%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2013) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2012) |

Max. 5.5%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Yes[36][37] (as of 30 Apr 2013) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2012)[38] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2012)[38] | |||||||

| 4.1% | Open (Closed in June 2013) | No | -5.2% | 6.36% | Unknown | |||

| 2.9% | 37.8% | |||||||

| 2014 ECB Report[nb 10] | Reference values | Max. 1.7%[nb 11] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2014) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2013) |

Max. 6.2%[nb 12] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Yes[39][40] (as of 30 Apr 2014) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2013)[41] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2013)[41] | |||||||

| 2.1% | None | No | 0.9% | 5.26% | No | |||

| 2.3% | 38.4% | |||||||

| 2016 ECB Report[nb 13] | Reference values | Max. 0.7%[nb 14] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

None open (as of 18 May 2016) | Min. 2 years (as of 18 May 2016) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2015) |

Max. 4.0%[nb 15] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

Yes[42][43] (as of 18 May 2016) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2015)[44] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2015)[44] | |||||||

| -1.3% | None | No | 0.0% | 3.6% | No | |||

| 0.7% | 38.4% | |||||||

| 2018 ECB Report[nb 16] | Reference values | Max. 1.9%[nb 17] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

None open (as of 3 May 2018) | Min. 2 years (as of 3 May 2018) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2017) |

Max. 3.2%[nb 18] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

Yes[45][46] (as of 20 March 2018) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2017)[47] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2017)[47] | |||||||

| 1.9% | None | No | -1.7% | 4.1% | No | |||

| 2.9% | 35.0% | |||||||

- Notes

- ↑ The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- ↑ The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- ↑ The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2012.[33]

- ↑ Sweden, Ireland and Slovenia were the reference states.[33]

- 1 2 3 4 5 The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- ↑ Sweden and Slovenia were the reference states, with Ireland excluded as an outlier.[33]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2013.[36]

- 1 2 Sweden, Latvia and Ireland were the reference states.[36]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2014.[39]

- ↑ Latvia, Portugal and Ireland were the reference states, with Greece, Bulgaria and Cyprus excluded as outliers.[39]

- ↑ Latvia, Ireland and Portugal were the reference states.[39]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2016.[42]

- ↑ Bulgaria, Slovenia and Spain were the reference states, with Cyprus and Romania excluded as outliers.[42]

- ↑ Slovenia, Spain and Bulgaria were the reference states.[42]

- ↑ Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2018.[45]

- ↑ Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[45]

- ↑ Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[45]

Coins design

Romanian euro coins have not yet been designed. Romanian law requires that the coat of arms of the country be used on coin designs.[51] In Romanian, the currency is called euro [ˈe.uro], and its subunit eurocent [e.uroˈt͡ʃent].

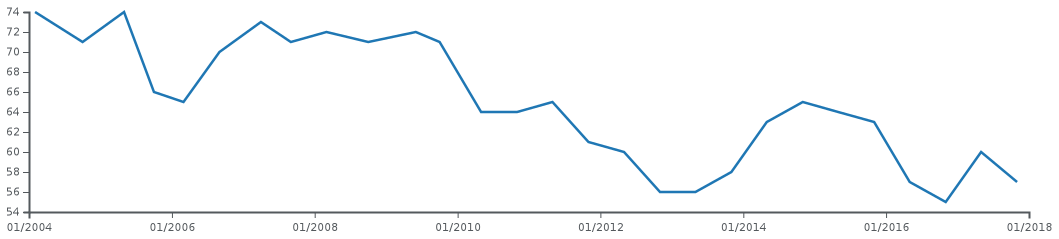

Public opinion

- Public support for the euro in Romania[52]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has received formal recognition as an independent state from 113 out of 193 United Nations member states.

References

- ↑ "Romania's ruling party congress votes to join euro in 2024". Reuters. 10 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ "Coins and notes in circulation". The National Bank of Romania. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- ↑ "Isarescu: Trecem la euro dupa 2012" (in Romanian). 18 May 2006. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ↑ Isarescu: Trecem la euro dupa 2012 | Eveniment | Ziarul Financiar Archived 17 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "ECB: Introductory statement with Q&A". ECB. 6 June 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ↑ "Raport privind situația macroeconomică" (PDF). Government of Romania. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ↑ "Romania to join the euro zone in 2015". Business Review. 1 November 2011.

- ↑ "Update: New Euro adoption target to be set by the end of the month, PM". Business-review.ro. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ↑ "The EIU view on Romania joining the Eurozone". 17 May 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ↑ "Resilient Romania Finds a Currency Advantage in a Crisis". The New York Times. 3 November 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ Banking News (22 June 2012). "Croitoru (BNR): Adoptarea monedei euro, un orizont indepartat". Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ "Government of Romania - Convergence Programme - 2013-2016" (PDF). Government of Romania. April 2013.

- 1 2 Trotman, Andrew (18 April 2013). "Romania abandons target date for joining euro". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ↑ "Opinion of the European Central Bank of 7 May 2013: On strengthening Banca Naţională a României's institutional role and independence (CON/2013/31)" (PDF). ECB. 7 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "Guvernul Romaniei - Programul de convergenta - 2014-2017" (PDF). Government of Romania. April 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Romania Sets 2019 as Target Date to Join Euro Area, Voinea Says". Bloomberg. 6 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "Erste: Romania in zona euro in 2019, un obiectiv „foarte ambitios". Realist ar fi dupa 2021" [Erste: Romania in the eurozone in 2019, a "very ambitious" goal. Realistically it would be after 2021.] (in Romanian). Wall-Street Romania. 19 May 2014.

- ↑ "Isarescu: Romania needs law to enforce 2019 Euro-adoption target". Business Review. 19 August 2014.

- ↑ "Opening speech delivered at the 2015 COFACE Country Risk Conference (Mugur Isărescu)". Banca Naţională a României. 29 April 2015.

- ↑ Vintilă, Carmen (2 June 2015). "Victor Ponta: Un referendum, înainte de a intra efectiv în zona euro, ar fi o măsură democratică". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Government of Romania Convergence Programme 2015-2018" (PDF). Government of Romania. April 2015.

- ↑ "Purchasing power parities (PPPs), price level indices and real expenditures for ESA2010 aggregates: GDP Volume indices of real expenditure per capita in PPS (EU28=100)". Eurostat. 16 June 2015.

- ↑ "Central Bank: Romania 2019 euro membership 'not feasible'". EUObserver. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ "Romania may join euro zone in 2022, says foreign minister - report". CNBC. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ↑ "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ↑ "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "General government gross debt (EDP concept), consolidated - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-20.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2012" (PDF). European Commission. March 2012. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2012" (PDF). European Commission. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-17.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2013" (PDF). European Commission. March 2013. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2013" (PDF). European Commission. February 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2014" (PDF). European Commission. March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - June 2016" (PDF). European Commission. June 2016. Retrieved 2016-06-07.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2016" (PDF). European Commission. May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Convergence Report 2018". European Central Bank. 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- ↑ "Convergence Report - May 208". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- 1 2 "European economic forecast - spring 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ↑ "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ↑ "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- 1 2 "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ↑ Chamber of Deputies of Romania, Law No. 102/September 21, 1992 regarding the Country Coat of Arms and the State Seal, Article 4

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/index#p=1&instruments=STANDARD&yearFrom=1999&yearTo=2017