Treaty of Rome

The signing ceremony of the Treaty at the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline Hill | |

| Type | Founding treaty |

|---|---|

| Signed | 25 March 1957 |

| Location | Capitoline Hill in Rome, Italy |

| Effective | 1 January 1958 |

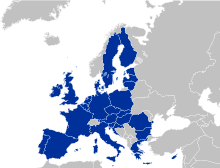

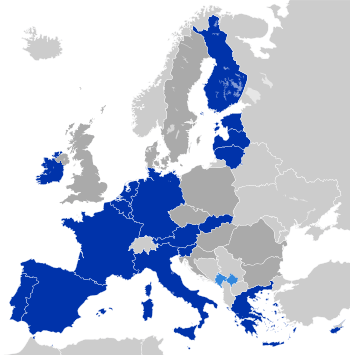

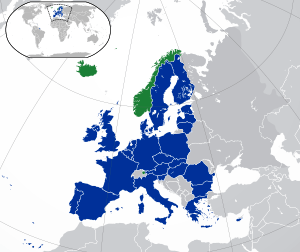

| Parties | EU member states |

| Depositary | Government of Italy |

|

| |

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU; also referred to as the Treaty of Rome) is one of two treaties forming the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU), the other being the Treaty on European Union (TEU; also referred to as the Treaty of Maastricht).

The Treaty of Rome brought about the creation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the best-known of the European Communities (EC). It was signed on 25 March 1957 by Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and West Germany and came into force on 1 January 1958. It remains one of the two most important treaties in the modern-day European Union (EU).

The TEEC proposed the progressive reduction of customs duties and the establishment of a customs union. It proposed to create a single market for goods, labour, services, and capital across the EEC's member states. It also proposed the creation of a Common Agriculture Policy, a Common Transport Policy and a European Social Fund, and established the European Commission.

The treaty's name has been retrospectively amended on several occasions since 1957. The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 removed the word "economic" from the Treaty of Rome's official title and, in 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon renamed it the "Treaty on the functioning of the European Union".

History

The TFEU originated as the treaty establishing the European Economic Community (the EEC treaty), signed in Rome on 25 March 1957. On 7 February 1992, the Maastricht treaty, which led to the formation of the European Union, saw the EEC Treaty renamed as the Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC) and renumbered. The Maastricht reforms also saw the creation of the European Union's three pillar structure, of which the European Community was the major constituent part.

Following the 2005 referenda, which saw the failed attempt at launching a European Constitution, on 13 December 2007 the Lisbon treaty was signed. This saw the 'TEC' renamed as the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and, once again, renumbered. The Lisbon reforms resulted in the merging of the three pillars into the reformed European Union.

Background

In 1951, the Treaty of Paris was signed, creating the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). The Treaty of Paris was an international treaty based on international law, designed to help reconstruct the economies of the European continent, prevent war in Europe and ensure a lasting peace.

The original idea was conceived by Jean Monnet, a senior French civil servant and it was announced by Robert Schuman, the French Foreign Minister, in a declaration on 9 May 1950. The aim was to pool Franco-West German coal and steel production, because the two raw materials were the basis of the industry (including war industry) and power of the two countries. The proposed plan was that Franco-West German coal and steel production would be placed under a common High Authority within the framework of an organisation that would be open for participation to other European countries. The underlying political objective of the European Coal and Steel Community was to strengthen Franco-German cooperation and banish the possibility of war.

France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands began negotiating the treaty. The Treaty Establishing the ECSC was signed in Paris on 18 April 1951, and entered into force on 24 July 1952. The Treaty expired on 23 July 2002, after fifty years, as was foreseen. The common market opened on 10 February 1953 for coal, iron ore and scrap, and on 1 May 1953 for steel.

Partly in the aim of creating a United States of Europe, two further Communities were proposed, again by the French. A European Defence Community (EDC) and a European Political Community (EPC). While the treaty for the latter was being drawn up by the Common Assembly, the ECSC parliamentary chamber, the EDC was rejected by the French Parliament. President Jean Monnet, a leading figure behind the Communities, resigned from the High Authority in protest and began work on alternative Communities, based on economic integration rather than political integration.[1]

As a result of the energy crises, the Common Assembly proposed extending the powers of the ECSC to cover other sources of energy. However, Monnet desired a separate Community to cover nuclear power, and Louis Armand was put in charge of a study into the prospects of nuclear energy use in Europe. The report concluded that further nuclear development was needed, in order to fill the deficit left by the exhaustion of coal deposits and to reduce dependence on oil producers. The Benelux states and West Germany were also keen on creating a general common market; however, this was opposed by France owing to its protectionist policy, and Monnet thought it too large and difficult a task. In the end, Monnet proposed creating both as separate Communities to attempt to satisfy all interests.[2] As a result of the Messina Conference of 1955, Paul-Henri Spaak was appointed as chairman of a preparatory committee, the Spaak Committee, charged with the preparation of a report on the creation of a common European market.

Move towards a Single Market

The Spaak Report[3] drawn up by the Spaak Committee provided the basis for further progress and was accepted at the Venice Conference (29 and 30 May 1956) where the decision was taken to organise an Intergovernmental Conference. The report formed the cornerstone of the Intergovernmental Conference on the Common Market and Euratom at Val Duchesse in 1956.

The outcome of the conference was that the new Communities would share the Common Assembly (now the Parliamentary Assembly) with the ECSC, as they would the European Court of Justice. However, they would not share the ECSC's Council of High Authority. The two new High Authorities would be called Commissions, from a reduction in their powers. France was reluctant to agree to more supranational powers; hence, the new Commissions would have only basic powers, and important decisions would have to be approved by the Council (of national Ministers), which now adopted majority voting.[4] Euratom fostered co-operation in the nuclear field, at the time a very popular area, and the European Economic Community was to create a full customs union between members.[5][6]

Signing

The conference led to the signing on 25 March 1957, of the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community and the Euratom Treaty at the Palazzo dei Conservatori on Capitoline Hill in Rome.

In March 2007, the BBC's Today radio programme reported that delays in printing the treaty meant that the document signed by the European leaders as the Treaty of Rome consisted of blank pages between its frontispiece and page for the signatures.[7][8][9]

Amendments

The Treaty of Rome, the original full name of which was the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community has been amended by successive treaties significantly changing its content. The 1992 Treaty of Maastricht established the European Union, the EEC becoming one of its three pillars, the European Community. Hence, the treaty was renamed the Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC).

When the Treaty of Lisbon came into force in 2009, the pillar system was abandoned; hence, the EC ceased to exist as a legal entity separate from the EU. This led to the treaty being amended and renamed as the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).[10]

In March 2011, the European Council adopted a decision to amend the Treaty by adding a new paragraph to Article 136. The additional paragraph, which enables the establishment of a financial stability mechanism for the Eurozone, runs as follows:

The Member States whose currency is the euro may establish a stability mechanism to be activated if indispensable to safeguard the stability of the euro area as a whole. The granting of any required financial assistance under the mechanism will be made subject to strict conditionality.[11]

For details of the content of the Treaty as it stands after 2009, see Treaties of the European Union#Treaty on the functioning of the European Union.

Anniversary commemorations

Major anniversaries of the signing of the Treaty of Rome have been commemorated in numerous ways.

Commemorative coins

Commemorative coins have been struck by numerous European countries, notably at the 30th and 50th anniversaries (1987 and 2007 respectively).

2007 celebrations in Berlin

In 2007, celebrations culminated in Berlin with the Berlin declaration preparing the Lisbon Treaty.

2017 celebrations in Rome

In 2017, Rome was the centre of multiple official[13][14][15] and popular celebrations.[16][17] Street demonstrations were largely in favour of European unity and integration, according to several news sources.[18][19][20][21]

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (2007) is one of two primary Treaties of the European Union, alongside the Treaty on European Union (TEU). Originating as the Treaty of Rome, the TFEU forms the detailed basis of European Union law, by setting out the scope of the EU's authority to legislate and the principles of law in those areas where EU law operates.

Historical assessment

According to the historian Tony Judt, the Treaty of Rome did not represent a fundamental turning point in the history of European integration:

It is important not to overstate the importance of the Rome Treaty. It represented for the most part a declaration of future good intentions...Most of the text constituted a framework for instituting procedures designed to establish and enforce future regulations. The only truly significant innovation – the setting up under Article 177 of a European Court of Justice to which national courts would submit cases for final adjudication – would prove immensely important in later decades but passed largely unnoticed at the time.[22]

Present contents

The consolidated TFEU consists of seven parts:

Part 1, Principles

In principles, article 1 establishes the basis of the treaty and its legal value. Articles 2 to 6 outline the competencies of the EU according to the level of powers accorded in each area. Articles 7 to 14 set out social principles, articles 15 and 16 set out public access to documents and meetings and article 17 states that the EU shall respect the status of religious, philosophical and non-confessional organisations under national law.[23]

Part 2, Non-discrimination and citizenship of the Union

The second part begins with article 18 which outlaws, within the limitations of the treaties, discrimination on the basis of nationality. Article 19 states the EU will "combat discrimination based on sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation". Articles 20 to 24 establishes EU citizenship and accords rights to it; to free movement, consular protection from other states, vote and stand in local and European elections, right to petition Parliament and the European Ombudsman and to contact and receive a reply from EU institutions in their own language. Article 25 requires the Commission to report on the implementation of these rights every three years.[23]

Part 3, Union policies and internal actions

Part 3 is the largest in the TFEU. Articles 26 to 197 concern the substantive policies and actions of the EU.

Title II: Free movement of goods

Including the customs union

Title III: Agriculture and Fisheries

Title IV: Free movement of workers, services and capital

Title V: Area of freedom, justice and security

Including police and justice co-operation

Title VII: Common Rules on Competition, Taxation and Approximation of Laws

European Union competition law, taxation and harmonisation of regulations (note Article 101 and Article 102)

Title VIII: Economic and monetary policy

Articles 119 to 144 concern economic and monetary policy, including articles on the euro. Chapter 1: Economic policy – Article 126 deals with how excessive member state debt is handled.[24] Chapter 2: Monetary policy – Article 127 outlines that the European System of Central Banks should maintain price stability and work with the principles of an open markets and free competition.[25] The Article 140 describes the criteria for inclusion in monetary union (the euro) or having exception from it, and also says that it is a majority of the council, not the state alone, which decides upon usage of euro or national currency. Thereby are states obliged (except UK and Denmark) to introduce the euro if the council finds they fulfil the criteria.

Titles IX to XV: Employment, social and consumer policy

Title IX concerns employment policy, under articles 145–150. Title X concerns social policy, and with reference to the European Social Charter 1961 and the Community Charter of the Fundamental Social Rights of Workers 1989. This gives rise to the weight of European labour law.

Title XI establishes the European Social Fund under articles 162–164. Title XII, articles 165 and 166 concern education, vocational training, youth and sport policies. Title XIII concerns culture, in article 167. Title XIV allows measures for public health, under article 168. Title XV empowers the EU to act for consumer protection, in article 169.

Titles XVI to XXIV Networks, industry, environment, energy, other

Title XVI, articles 170–172 empower action to develop and integrate Trans-European Networks. Title XVII, article 173, regards the EU's industrial policy, to promote industry. Title XVIII, articles 174 to 178 concern economic, social and territorial cohesion (reducing disparities in development). Title XIX concerns research and development and space policy, under which the European Research Area and European Space Policy are developed.

Title XX concerns the increasingly important environmental policy, allowing action under articles 191 to 193. Title XXI, article 194, establishes the Energy policy of the European Union.

Title XXII, article 195 is tourism. Title XXIII, article 196 is civil protection. Title XXIV, article 197 is administrative co-operation.

Part 4, Association of the overseas countries and territories

Part 4, in articles 198 to 204, deals with association of overseas territories. Article 198 sets the objective of association as promoting the economic and social development of those associated territories as listed in annexe 2. The following articles elaborate on the form of association such as customs duties.[23]

Part 5, External action by the Union

Part 5, in articles 205 to 222, deals with EU foreign policy. Article 205 states that external actions must be in accordance with the principles laid out in Chapter 1 Title 5 of the Treaty on European Union. Article 206 and 207 establish the common commercial (external trade) policy of the EU. Articles 208 to 214 deal with co-operation on development and humanitarian aid for third countries. Article 215 deals with sanctions while articles 216 to 219 deal with procedures for establishing international treaties with third countries. Article 220 instructs the High Representative and Commission to engage in appropriate co-operation with other international organisations and article 221 establishes the EU delegations. Article 222, the Solidarity clause states that members shall come to the aid of a fellow member who is subject to a terrorist attack, natural disaster or man-made disaster. This includes the use of military force.[23]

Part 6, Institutional and financial provisions

Part 6, in articles 223 to 334, elaborates on the institutional provisions in the Treaty on European Union. As well as elaborating on the structures, articles 288 to 299 outline the forms of legislative acts and procedures of the EU. Articles 300 to 309 establish the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank. Articles 310 to 325 outline the EU budget. Finally, articles 326 to 334 establishes provision for enhanced co-operation.[23]

Part 7, General and final provisions

Part 7, in articles 335 to 358, deals with final legal points, such as territorial and temporal application, the seat of institutions (to be decided by member states, but this is enacted by a protocol attached to the treaties), immunities and the effect on treaties signed before 1958 or the date of accession.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Raymond F. Mikesell, The Lessons of Benelux and the European Coal and Steel Community for the European Economic Community, The American Economic Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Seventieth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 1958), pp. 428–441

- ↑ 1957–1968 Successes and crises – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ↑ The Brussels Report on the General Common Market (abridged, English translation of document commonly called the Spaak Report) – AEI (Archive of European Integration)

- ↑ Drafting of the Rome Treaties – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ↑ A European Atomic Energy Community – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ↑ A European Customs Union – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- ↑ What really happened when the Treaty of Rome was signed 50 years ago

- ↑ EU landmark document was 'blank pages'

- ↑ How divided Europe came together

- ↑ "Presidency Conclusions Brussels European Council 21/22 June 2007" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 23 June 2007.

- ↑ The European Treaty Amendment for the Creation of a Financial Stability Mechanism (Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies)

- ↑ FAZ

- ↑ "European Commission – PRESS RELEASES – Press release – Rome Declaration of the Leaders of 27 Member States and of the European Council, the European Parliament and the European Commission". europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "Speech by President Donald Tusk at the ceremony of the 60th anniversary of the Treaties of Rome – Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "European Commission – PRESS RELEASES – Press release – Speech by President Juncker at the 60th Anniversary of the Treaties of Rome celebration – A new chapter for our Union: shaping the future of EU 27". europa.eu. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "Cortei Roma, il raduno dei federalisti. "L'Europa è anche pace, solidarietà e diritti"". Il Fatto Quotidiano (in Italian). 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "Celebrazioni Ue, in 5 mila al corteo europeista". Repubblica.it (in Italian). 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "A Rome, plusieurs milliers de manifestants défilent pour «un réveil de l'Europe»". Libération.fr (in French). Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "Des milliers de manifestants en marge des 60 ans du traité de Rome". Le Monde.fr (in French). 2017-03-25. ISSN 1950-6244. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "Pro-European, Anti-Populist Protesters March as EU Leaders Meet in Rome". Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ "Trattati di Roma, cortei e sit-in: la giornata in diretta" (in Italian). Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ Judt, Tony (2007). Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. London: Pimlico. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-7126-6564-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union" (PDF). Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "EUR-Lex – 12008E126 – EN – EUR-Lex".

- ↑ "EUR-Lex – 12008E127 – EN – EUR-Lex".

External links

- Documents of Treaty of Rome's negotiations are at the Historical Archives of the EU in Florence

- History of the Rome Treaties – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- Treaty establishing the European Economic Community – CVCE (Centre for European Studies)

- Happy Birthday EU — Union wide design competition to mark the 50th anniversary of the Treaty

- 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome – Official Site