Common Security and Defence Policy

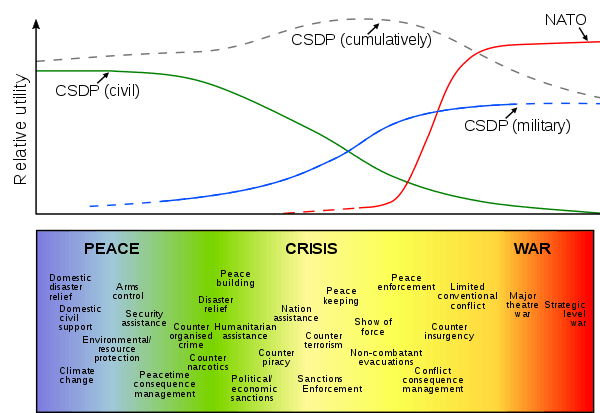

The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) is the European Union's (EU) course of action in the fields of defence and crisis management, and a main component of the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP).

The implementation of the CSDP involves the deployment of military or civilian missions for peace-keeping, conflict prevention and strengthening international security in accordance with the principles of the United Nations Charter. Military missions are carried out by EU forces established with contributions from the member states' armed forces. The CSDP also entails collective self-defence amongst member states[lower-alpha 4] as well as a Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in which 25 of the 28 national armed forces pursue structural integration.

The Union's High Representative (HR/VP), currently Federica Mogherini, is responsible for proposing and implementing CSDP decisions. Such decisions are adopted by the Foreign Affairs Council (FAC), generally requiring unanimity. The CSDP structure, headed by the HR/VP, comprise relevant sections of the External Action Service (EEAS) — including the Military Staff (EUMS) with its operational headquarters (MPCC) — a number of FAC preparatory bodies — such as the Military Committee (EUMC) — as well as four agencies, including the Defence Agency (EDA). The CSDP structure is sometimes referred to as the European Defence Union (EDU), especially in relation to its prospective development as the EU's defence arm.[3][4][5][lower-alpha 5]

History

The post-war period saw several short-lived or ill-fated initiatives for European defence integration intended to protect against potential Soviet or German aggression: The Western Union and the proposed European Defence Community were respectively cannibalised by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and rejected by the French Parliament. The largely dormant Western European Union (WEU) succeeded the Western Union's remainder in 1954.

In 1970 the European Political Cooperation (EPC) brought about the European Communities' (EC) initial foreign policy coordination. Opposition to the addition of security and defence matters to the EPC led to the reactivation of the WEU in 1984 by its member states, which were also EC member states.

After the end of the Cold War, European defence integration gained momentum. In 1992, the WEU was given new tasks, and the following year the Treaty of Maastricht founded the EU and replaced the EPC with the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) pillar. In 1996 NATO agreed to let the WEU develop a European Security and Defence Identity (ESDI).[6] The 1998 St. Malo declaration signalled that the traditionally hesitant United Kingdom was prepared to provide the EU with autonomous defence structures.[7] This facilitated the transformation of the ESDI into the European Security and Defence Policy (ESDP) in 1999, when it was transferred to the EU. In 2003 the EU deployed its first CSDP missions, and adopted the European Security Strategy identifying common threats and objectives. In 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon introduced the present name, CSDP, while establishing the EEAS, the mutual defence clause and enabling a subset of member states to pursue defence integration within PESCO. In 2011 the WEU, whose tasks had been transferred to the EU, was dissolved. In 2016 a new security strategy was introduced, which along with the Russian annexation of Crimea, the scheduled British withdrawal from the EU and the election of Trump as US President have given the CSDP a new impetus.

Deployments

In the EU terminology, civilian CSDP interventions are called ‘missions’, regardless of whether they have an executive mandate such as EULEX Kosovo or a non-executive mandate (all others). Military interventions, however, can either have an executive mandate such as for example Operation Atalanta in which case they are referred to as ‘operations’ and are commanded at two-star level; or non-executive mandate (e.g. EUTM Somalia) in which case they are called ‘missions’ and are commanded at one-star level.

The first deployment of European troops under the ESDP, following the 1999 declaration of intent, was in March 2003 in the Republic of Macedonia. Operation Concordia used NATO assets and was considered a success and replaced by a smaller police mission, EUPOL Proxima, later that year. Since then, there have been other small police, justice and monitoring missions. As well as the Republic of Macedonia, the EU has maintained its deployment of peacekeepers in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as part of Operation Althea.[9]

Between May and September 2003 EU troops were deployed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) during "Operation Artemis" under a mandate given by UN Security Council Resolution 1484 which aimed to prevent further atrocities and violence in the Ituri Conflict and put the DRC's peace process back on track. This laid out the "framework nation" system to be used in future deployments. The EU returned to the DRC during July–November 2006 with EUFOR RD Congo, which supported the UN mission there during the country's elections.

Geographically, EU missions outside the Balkans and the DRC have taken place in Georgia, Indonesia, Sudan, Palestine, and Ukraine–Moldova. There is also a judicial mission in Iraq (EUJUST Lex). On 28 January 2008, the EU deployed its largest and most multi-national mission to Africa, EUFOR Tchad/RCA.[10] The UN-mandated mission involves troops from 25 EU states (19 in the field) deployed in areas of eastern Chad and the north-eastern Central African Republic in order to improve security in those regions. EUFOR Tchad/RCA reached full operation capability in mid-September 2008, and handed over security duties to the UN (MINURCAT mission) in mid-March 2009.[11]

The EU launched its first maritime CSDP operation on 12 December 2008 (Operation Atalanta). The concept of the European Union Naval Force (EU NAVFOR) was created on the back of this operation, which is still successfully combatting piracy off the coast of Somalia almost a decade later. A second such intervention was launched in 2015 to tackle migration problems in the southern Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR Med), working under the name Operation SOPHIA.

Most of the CSDP missions deployed so far are mandated to support Security Sector Reforms (SSR) in host-states. One of the core principles of CSDP support to SSR is local ownership. The EU Council defines ownership as "the appropriation by the local authorities of the commonly agreed objectives and principles".[12] Despite EU's strong rhetorical attachment to the local ownership principle, research shows that CSDP missions continue to be an externally driven, top-down and supply-driven endeavour, resulting often in the low degree of local participation.[13]

Structure

The CSDP is a part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), based on articles 42–46 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU)[14][15]. Article 42.2 of TEU states that the CSDP includes the 'progressive framing' of a common Union defence policy, and will lead to a common defence, when the European Council of national heads of state or government, acting unanimously, so decides.

Denmark has an opt-out from the CSDP.[2]

The CSDP command structure involving the High Representative, the Military Staff and Military Committee as of 1 November 2017:[16]

Colour key:

High Representative (a Vice-President of the Commission)

![]()

![]()

| High Representative | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Military Committee Chairman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Working Group | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Working Group/Headline Goal Task Force | Military Staff Director General | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Legal advisor | Deputy Director General | Horizontal Coordination | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assistant Chief of Staff for Synchronisation | EU cell at SHAPE | EU Liaison at the UN in NY | Assistant Chief of Staff for External Relations | NATO Permanent Liaison Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Directorate A: Concepts & Capabilities | Directorate B: Intelligence | Directorate C: Operations | Directorate D: Logistics | Directorate E: Communications & Information Systems | Military Planning and Conduct Capability

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

High Representative

The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, commonly referred to as the High Representative (HR/VP), is the chief co-ordinator and representative of the EU's Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), including the CSDP. The position is currently held by Federica Mogherini.

Where foreign matters is agreed between EU member states, the High Representative can speak for the EU in that area, such as negotiating on behalf of the member states.

Beside representing the EU at international fora and co-ordinating the CFSP and the CSDP, the HR/VP is:

- ex-officio Vice-President of the European Commission

- participant in the meetings of the European Council

- responsible of the European Union Special Representatives

- head of the External Action Service and the delegations

- President of the Foreign Affairs Council

- Head of the European Defence Agency

- Chairperson of the board of the European Union Institute for Security Studies

External Action Service

The European External Action Service (EEAS) is the diplomatic service and foreign and defence ministry of the EU. The EEAS is led by the HR/VP and seated in Brussels.

The EEAS does not propose or implement policy in its own name, but prepares acts to be adopted by the HR/VP, the European Commission or the Council.[17] The EEAS is also in charge of EU diplomatic missions (delegations)[18] and intelligence and crisis management structures.[19][20][21]

The following EEAS bodies take part in managing the CSDP:

- The Military Staff (EUMS) is an EEAS Directorate-General that provides strategic advice to the HR/VP and commands non-combat operations through its Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) operational headquarters.[22][23] The EUMS also reports to the European Union Military Committee (EUMC), representing member states' Chiefs of Defence, and performs "early warning", situation assessment and strategic planning. The EUMS currently consists of 200+ military and civilian personnel. The EUMS and the European Defence Agency (EDA) together form the Secretariat of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), the structural integration pursued by 25 of the 28 national armed forces of the EU since 2017.[24]

- The Intelligence and Situation Centre (EU INTCEN)

- The Security and Defence College (ESDC) is a virtual institution for strategic level training. The ESDC consists of a network of various national institutions, such as defence colleges, and the European Union Institute for Security Studies.[25] The ESDC initiated the European initiative for the exchange of young officers inspired by Erasmus, often referred to as military Erasmus, exchanging between armed forces of future military officers as well as their teachers and instructors during their initial education[26] and training. Due to the fact that the initiative is implemented by the Member States on a purely voluntary basis, their autonomy with regard to military training is not compromised.

- The Crisis Management and Planning Directorate (CMPD)

- The Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC)

Council preparatory bodies

.jpg)

The Council of the European Union has the following, Brussels-based preparatory bodies in the field of CSDP:

- The Political and Security Committee (PSC) consists of ambassadorial level representatives from the EU member states and usually meets twice per week.[27] The PSC is chaired by the External Action Service. Ambassador Walter Stevens has been the PSC permanent Chair since June 2013[28] The main functions of the PSC are keeping track of the international situation, and helping to define EU policies within the CFSP and CSDP.[29] PSC sends guidance to, and receives advice from the European Union Military Committee (EUMC), the Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management (CIVCOM) as well as the European Union Institute for Security Studies. It is also a forum for dialogue on CSDP matters between the EU Member States. PSC also drafts opinions for the Foreign Affairs Council, which is one of the configurations of the Council of the European Union. CFSP matters are passed to the Foreign Affairs Council via COREPER II.

- The European Union Military Committee (EUMC) is composed of member states' Chiefs of Defence (CHOD). These national CHODs are regularly represented in the EUMC in Brussels by their permanent Military Representatives (MilRep), who often are two- or three-star flag officers. The EUMC is under the under authority of the EU's High Representative (HR) and the Political and Security Committee (PSC). The EUMC gives military advice to the EU's High Representative (HR) and Political and Security Committee (PSC). The EUMC also oversees the European Union Military Staff (EUMS).

- The Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management (CIVCOM) is an advisory body dealing with civilian aspects of crisis management. The activities of CIVCOM therefore forms part of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of EU, and the civilian side of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). CIVCOM is composed of representatives of the EU member states. The activities of CIVCOM for civilian CSDP tasks occur in parallel to the European Union Military Committee (EUMC) for military CDP tasks. Both EUMC and CIVCOM receive directions from, and report to the Political and Security Committee (PSC). The decision to establish CIVCOM was taken in 2000 by the Council of the European Union.[30]

- The Politico-Military Group (PMG) carries out preparatory work for the Political and Security Committee (PSC). It covers the political aspects of EU military and civil-military issues, including concepts, capabilities and operations and missions.[31] The tasks of the PMG include: 1) preparing Council conclusions and provides recommendations for the PSC, and monitoring their effective implementation 2) contributing to the development of horisontal policy and facilitating information exchanges. The PMG has a particular responsibility regarding partnerships with non-EU countries and other organisations, including EU-NATO relations, as well as exercises. The PMG is chaired by a representative of the HR/VP.

Mission/operational headquarters

The Council nominates headquarters for each mission, referred to as mission headquarters. Military CSDP missions with elements of combat are also referred to as operations, in which case the headquarters are referred to as operational headquarters (OHQs). The selected OHQ runs the operation at the strategic level and directs the force headquarters (FHQ), which carries out the operation on the ground.

| Type | Name | Abbreviation | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent headquarters within the External Action Service's Military Staff (EUMS) Directorate-General | MPCC | Brussels, Belgium | |

| Headquarters of Allied Command Operations (ACO), made available by NATO | SHAPE | Mons, Belgium | |

| National parent headquarters made available by member states | CPCO | Paris, France | |

| EinsFüKdoBw | Potsdam, Germany | ||

| EL EU OHQ | Larissa, Greece | ||

| ITA-JFHQ | Centocelle, Rome, Italy | ||

| MNHQ | Northwood Headquarters, London, United Kingdom | ||

| NAVSTA Rota | Rota, Spain |

Additionally, Local Mission Headquarters may be established in the country in which a training mission (EUTM) takes place. Examples: EUTMs in Somalia and Mali have local Mission Headquarters situated in Mogadishu, Somalia and Bamako, Mali, respectively.

Between 2012 and 2016 another mechanism was employed, with which an Operations Centre (EU OPCEN) would be established to plan and conduct military operations. This was a non-standing, ad-hoc headquarters that would be operational five days following a decision by the Council, and would reach its full capability to command the operation after twenty days, at the latest. Such EU OPCENs has no command responsibility, and was separate from established chains of command.[35]

Agencies

The following agencies relate to the CSDP:

- The Defence Agency (EDA), based in Brussels, facilitates the improvement of national military capabilities and integration. In that capacity, it makes proposals, coordinates, stimulates collaboration, and runs projects.

- The Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex), based in Warsaw, Poland, leads the European coast guard that controls the borders of the Schengen Area.

- The Institute for Security Studies (ISS), based in Paris, is an autonomous think tank that researches EU-relevant security issues. The research results are published in papers, books, reports, policy briefs, analyses and newsletters. In addition, the institute convenes seminars and conferences on relevant issues that bring together EU officials, national experts, decision-makers and NGO representatives from all Member States.

- The Satellite Centre (SatCen), located in Torrejón de Ardoz, Spain, supports the decision-making by providing products and services resulting from the exploitation of relevant space assets and collateral data, including satellite and aerial imagery, and related services.

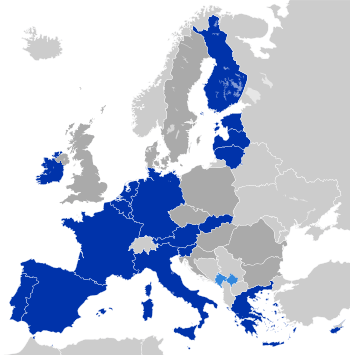

Permanent structured cooperation

The Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) is the framework in which 25 of the 28 national armed forces pursue structural integration. Based on Article 42.6 and Protocol 10 of the Treaty on European Union, introduced by the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009, PESCO was first initiated in 2017.[36] The initial integration within the PESCO format is a number of projects planned to launch in 2018.[37]

PESCO is similar to enhanced co-operation in other policy areas, in the sense that integration does not require that all EU member states participate.

Strategy

The European Union Global Strategy (EUGS) is the updated doctrine of the EU to improve the effectiveness of the CSDP, including the defence and security of the members states, the protection of civilians, cooperation between the member states' armed forces, management of immigration, crises etc. Adopted on 28 June 2016[38], it replaces the European Security Strategy of 2003. The EUGS is complemented by a document titled "Implementation Plan on Security and Defense" (IPSD)[39].

Forces

National

The CSDP is implemented using civilian and military contributions from member states' armed forces, which also are obliged to collective self-defence based on Treaty on European Union (TEU).

Six EU states host nuclear weapons: France and the United Kingdom each have their own nuclear programmes, while Belgium, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands host US nuclear weapons as part of NATO's nuclear sharing policy. Combined, the EU possesses 525 warheads, and hosts between 90 and 130 US warheads. Italy hosts 70-90 B61 nuclear bombs, while Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands 10-20 each one. [41] The EU has the third largest arsenal of nuclear weapons, after the United States and Russia.

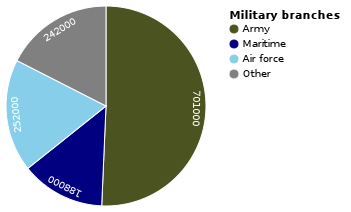

Expenditure and personnel

The following table presents the military expenditures of the members of the European Union in euros (€). The combined military expenditure of the member states amounts to just over is €192.5 billion.[2] This represents 1.55% of European Union GDP and is second only to the €503 billion military expenditure of the United States. The US figure represents 4.66% of United States GDP.[42] European military expenditure includes spending on joint projects such as the Eurofighter Typhoon and joint procurement of equipment. The European Union's combined active military forces in 2011 totaled 1,551,038 personnel. According to the European Defence Agency, the European Union had an average of 53,744 land force personnel deployed around the world (or 3.5% of the total military personnel). In a major operation the EU could readily deploy up-to 425,824 land force personnel and sustain 110,814 of those during an enduring operation.[42] In comparison, the US had on average 177,700 troops deployed in 2011. This represents 12.5% of US military personnel.[42]

In a speech in 2012, Swedish General Håkan Syrén criticised the spending levels of European Union countries, saying that in the future those countries' military capability will decrease, creating "critical shortfalls".[43]

Guide to table:

- All figure entries in the table below are provided by the European Defence Agency for the year 2012. Figures from other sources are not included.

- The "operations & maintenance expenditure" category may in some circumstances also include finances on-top of the nations defence budget.

- The categories "troops prepared for deployed operations" and "troops prepared for deployed and sustained operation" only include land force personnel.

| Member state | Expenditure (€ mn.) | Per capita (€) | % of GDP | Operations & maintenance expenditure (€ mn.) | Active military personnel | Land troops prepared for deployed and sustained operations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,453 | 291 | 0.82 | 507 | 27,110 | ||

| 3,986 | 363 | 1.08 | 651 | 31,894 | 1,897 | |

| 545 | 73 | 1.42 | 111 | 28,767 | 900 | |

| 610 | 146 | 1.41 | 18,000 | |||

| 345 | 400 | 1.92 | 50 | 12,392 | ||

| 1,820 | 173 | 1.17 | 501 | 22,129 | 1,350 | |

| 3,020 | 535 | 1.16 | 24,509 | |||

| 340 | 254 | 2.00 | 101 | 3,190 | 188 | |

| 2,654 | 493 | 1.40 | 705 | 8,844 | ||

| 39,105 | 597 | 1.93 | 7,613 | 218,200 | 29,444 | |

| 32,490 | 397 | 1.23 | 191,721 | |||

| 3,272 | 290 | 1.69 | 738 | 109,070 | 2,552 | |

| 1,000 | 100 | 1.00 | 329 | 18,088 | 1,057 | |

| 881 | 196 | 0.55 | 89 | 9,450 | 850 | |

| 20,600 | 338 | 1.32 | 2,087 | 184,318 | ||

| 210 | 102 | 1.04 | 45 | 4,832 | 212 | |

| 462 | 83 | 1.11 | 55 | 15,800 | 413 | |

| 201 | 386 | 0.47 | 21 | 1057 | 44 | |

| 40 | 96 | 0.62 | 6 | 1,698 | 30 | |

| 8,156 | 489 | 1.35 | 2,128 | 44,655 | 5,050 | |

| 6,754 | 175 | 1.95 | 1,331 | 120,000 | 4,946 | |

| 2,669 | 251 | 1.56 | 253 | 35,254 | 2,254 | |

| 1,713 | 80 | 1.26 | 189 | 68,340 | 2,953 | |

| 763 | 140 | 1.10 | 168 | 13,501 | 722 | |

| 478 | 233 | 1.32 | 81 | 7,107 | 454 | |

| 10,059 | 218 | 0.95 | 1,742 | 124,561 | 7,850 | |

| 4,331 | 459 | 1.12 | 1,847 | 13,949 | 1,966 | |

| 43,696 | 691 | 2.30 | 17,052 | 205,810 | 19,000 | |

| 192,535 | 387 | 1.55 | 45,219 | 1,551,038 | 110,814 |

Naval forces

_underway_2009.jpg)

The combined component strength of the naval forces of member states is some 564 commissioned warships. Of those in service, 5 are fleet carriers, the largest of which is the 70,600 tonne Queen Elizabeth-class. The EU also has 5 amphibious assault ships and 25 amphibious support ships in service. Of the EU's 60 submarines, 21 are nuclear-powered submarines (11 British and 10 French) while 39 are conventional attack submarines.

Operation Atalanta (formally European Union Naval Force Somalia) is the first ever (and still ongoing) naval operation of the European Union. It is part of a larger global action by the EU in the Horn of Africa to deal with the Somali crisis. As of January 2011 twenty-three EU nations participate in the operation.

France, Italy and United Kingdom have blue-water navies.[44]

Guide to table:

- Ceremonial vessels, research vessels, supply vessels, training vessels, and icebreakers are not included.

- The table only counts warships that are commissioned (or equivalent) and active.

- Surface vessels displacing less than 200 tonnes are not included, regardless of other characteristics.

- The "amphibious support ship" category includes amphibious transport docks and dock landing ships, and tank landing ships.

- Frigates over 6,000 tonnes are classified as destroyers.

- The "patrol vessel" category includes missile boats.

- The "anti-mine ship" category includes mine countermeasures vessels, minesweepers and minehunters.

- Generally, total tonnage of ships is more important than total number of ships, as it gives a better indication of capability.

| Member state | Fleet carrier | Amphibious assault ship | Amphibious support ship | Destroyer | Frigate | Corvette | Patrol vessel | Anti‑mine ship | Missile sub. | Attack sub. | Total | Tonnage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 10,009 | ||||||||

| 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 18 | 15,160 | ||||||

| 5 | 2 | 7 | 2,869 | |||||||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| 5 | 4 | 9 | 18 | 51,235 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | 2,000 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 12 | 20 | 5,429 | ||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 11 | 20 | 18 | 4 | 6 | 76 | 319,195 | ||

| 3 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 4 | 44 | 82,790 | |||||

| 5 | 13 | 26 | 4 | 8 | 51 | 137,205 | ||||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| 8 | 8 | 11,219 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 14 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 57 | 303,411 | |||

| 5 | 5 | 3,025 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 5,678 | |||||||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 400 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 22 | 116,308 | |||||

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 19 | 3 | 28 | 19,724 | |||||

| 5 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 23 | 34,686 | |||||||

| 3 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 21 | 23,090 | |||||||

| 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 900 | ||||||||||

| (1)[f] | 1[f] | 2 | 5 | 6 | 23 | 6 | 3 | 46 | 148,607 | |||

| 6 | 11 | 5 | 22 | 14,256 | ||||||||

| 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 13 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 7 | 57 | 367,850 | ||

| 5 | 5 | 25 | 31 | 93 | 48 | 128 | 151 | 8 | 52 | ~564 | ~1,500,000 |

Land forces

Combined, the member states of the European Union maintain large numbers of various land-based military vehicles and weaponry.

Guide to table:

- The table is not exhaustive and primarily includes vehicles and EU-NATO member countries under the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty (CFE treaty). Unless otherwise specified.

- The CFE treaty only includes vehicles stationed within Europe, vehicles overseas on operations are not counted.

- The "main battle tank" category also includes tank destroyers (such as the Italian B1 Centauro) or any self-propelled armoured fighting vehicle, capable of heavy firepower. According to the CFE treaty.

- The "armoured fighting vehicle" category includes any armoured vehicle primarily designed to transport infantry and equipped with an automatic cannon of at least 20 mm calibre. According to the CFE treaty.

- The "artillery" category includes self-propelled or towed howitzers and mortars of 100 mm calibre and above. Other types of artillery are not included regardless of characteristics. According to the CFE treaty.

- The "attack helicopter" category includes any rotary wing aircraft armed and equipped to engage targets or equipped to perform other military functions (such as the Apache or the Wildcat). According to the CFE treaty.

- The "military logistics vehicle" category includes logistics trucks of 4-tonne, 8-tonne, 14-tonne or larger, purposely designed for military tasking. Not under CFE treaty.

| Member state | Main battle tank | Armoured fighting vehicle | Artillery | Attack helicopter | Military logistics vehicle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | 364 | 73 | |||

| 0 | 226 | 133 | 27 | ||

| 362 | 681 | 1,035 | 12 | ||

| 75 | 283 | 127 | 10 | ||

| 123 | 501 | 182 | 24 | ||

| 46 | 229 | 56 | 12 | ||

| 74 | |||||

| 128 | 1,080 | 656 | 25 | ||

| 450 | 6,256 | 349 | 283 | 10,746 | |

| 815 | 1,774 | 401 | 158 | ||

| 1,622 | 2,187 | 1,920 | 29 | ||

| 155 | 597 | 300 | 23 | ||

| 107 | 36 | ||||

| 1,176 | 3,145 | 1,446 | 107 | 10,921 | |

| 96 | |||||

| 16 | 634 | 135 | 21 | ||

| 1,675 | 3,110 | 1,580 | 83 | ||

| 220 | 425 | 377 | |||

| 857 | 1,272 | 1,273 | 23 | ||

| 30 | 327 | 68 | |||

| 54 | |||||

| 484 | 1,007 | 811 | 27 | ||

| 427 | 5,278 | 658 | 190 | 12,344 | |

| 7,695 | 18,819 | 9,817 | 963 |

Air forces

The air forces of EU member states operate a wide range of military systems and hardware. This is primarily due to the independent requirements of each member state and also the national defence industries of some member states. However such programmes like the Eurofighter Typhoon and Eurocopter Tiger have seen many European nations design, build and operate a single weapons platform. 60% of overall combat fleet was developed and manufactured by member states, 32% are US-origin, but some of these were assembled in Europe, while remaining 8% are soviet-made aircraft. As of 2014, it is estimated that the European Union had around 2,000 serviceable combat aircraft (fighter aircraft and ground-attack aircraft).[68]

The EUs air-lift capabilities are evolving with the future introduction of the Airbus A400M (another example of EU defence cooperation). The A400M is a tactical airlifter with strategic capabilities.[69] Around 140 are initially expected to be operated by 6 member states (UK, Luxembourg, France, Germany, Spain and Belgium).

Guide to tables:

- The tables are sourced from figures provided by Flight International for the year 2014.

- Aircraft are grouped into three main types (indicated by colours): red for combat aircraft, green for aerial refueling aircraft, and grey for strategic and tactical transport aircraft.

- The two "other" columns include additional aircraft according to their type sorted by colour (i.e. the "other" category in red includes combat aircraft, while the "other" category in grey includes both aerial refueling and transport aircraft). This was done because it was not feasible allocate every aircraft type its own column.

- Other aircraft such as trainers, helicopters, UAVs and reconnaissance or surveillance aircraft are not included in the below tables or figures.

- Fighter and ground-attack

| Member state | Typhoon | Rafale | Mirage 2000 | Gripen | F-16 | F/A-18 | F-35 | Tornado | Harrier II | MiG-29 | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 15 | |||||||||||

| 59 | 59 | |||||||||||

| 15 | 15 | |||||||||||

| 12 MiG-21 | 12 | |||||||||||

| 14 | 19 L-159 | 33 | ||||||||||

| 60 | 60 | |||||||||||

| 62 | 62 | |||||||||||

| 131 | 94 | 17 Super Étendard | 242 | |||||||||

| 117 | 116 | 233 | ||||||||||

| 43 | 166 | 46 F-4 | 255 | |||||||||

| 14 | 14 | |||||||||||

| 90 | 9 | 75 | 16 | 55 AMX | 245 | |||||||

| 1 L-39 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 87 | 2 | 89 | ||||||||||

| 48 | 31 | 36 Su-22 | 115 | |||||||||

| 31 | 31 | |||||||||||

| 12 | 36 MiG-21 | 48 | ||||||||||

| 12 | 7 L-39 | 19 | ||||||||||

| 45 | 86 | 17 | 148 | |||||||||

| 95 | 95 | |||||||||||

| 160 | 4 | 87 | 251 | |||||||||

| 427 | 131 | 137 | 123 | 463 | 148 | 15 | 278 | 33 | 58 | 229 | 2,042 |

- Aerial refueling and transport

| Member state | A330 MRTT | A310 MRTT | KC-135/707 | C-17 | C-130 | C-160 | C-27J | CN-235/C-295 | An-26 | A400M | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5 | |||||||||||

| 11 | 1 A321 | 12 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 1 A319 | 5 | |||||||||

| 4 | 2 An-32B | 6 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 6 | 2 A319 | 12 | |||||||||

| 4 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 1 F27 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 14 | 14 | 36 | 27 | 6 | 3 A310 3 A340 | 99 | ||||||

| 4 | 71 | 1 | 1 A310 2 A319 | 76 | ||||||||

| 13 | 8 | 21 | ||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 1 BNT-2 CC2/B | 3 | ||||||||||

| 16 | 12 | 4 KC-767 3 KC-130J 3 A319 | 38 | |||||||||

| 3 | 3 | |||||||||||

| 2 BNT-2 CC2/B 2 King Air 200 |

4 | |||||||||||

| 4 | 2 (K)DC-10 | 6 | ||||||||||

| 5 | 16 | 20 | ||||||||||

| 6 | 7 | 13 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 7 | 2 | 11 | |||||||||

| 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 7 | 21 | 5 KC-130H 2 A310 | 37 | ||||||||

| 7 | 1 KC-130H | 8 | ||||||||||

| 11 | 8 | 24 | 4 | 4 BAe 146 3 BNT-2 CC2/B | 54 | |||||||

| 11 | 4 | 16 | 8 | 107 | 107 | 30 | 81 | 16 | 11 | 48 | 435 |

Multinational

Established at Union level

.jpg)

The Helsinki Headline Goal Catalogue is a listing of rapid reaction forces composed of 60,000 troops managed by the European Union, but under control of the countries who deliver troops for it.

Forces introduced at Union level include:

- The battle groups (BG) adhere to the CSDP, and are based on contributions from a coalition of member states. Each of the eighteen Battlegroups consists of a battalion-sized force (1,500 troops) reinforced with combat support elements.[70][71] The groups rotate actively, so that two are ready for deployment at all times. The forces are under the direct control of the Council of the European Union. The Battlegroups reached full operational capacity on 1 January 2007, although, as of January 2013 they are yet to see any military action.[72] They are based on existing ad hoc missions that the European Union (EU) has undertaken and has been described by some as a new "standing army" for Europe.[71] The troops and equipment are drawn from the EU member states under a "lead nation". In 2004, United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan welcomed the plans and emphasised the value and importance of the Battlegroups in helping the UN deal with troublespots.[73]

- The Medical Command (EMC) is a planned medical command centre in support of EU missions, formed as part of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO).[74] The EMC will provide the EU with a permanent medical capability to support operations abroad, including medical resources and a rapidly deployable medical task force. The EMC will also provide medical evacuation facilities, triage and resuscitation, treatment and holding of patients until they can be returned to duty, and emergency dental treatment. It will also contribute to harmonising medical standards, certification and legal (civil) framework conditions.[37]

- The Force Crisis Response Operation Core (EUFOR CROC) is a flagship defence project under development as part of Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). EURFOR CROC will contribute to the creation of a "full spectrum force package" to speed up provision of military forces and the EU's crisis management capabilities.[75] Rather than creating a standing force, the project involves creating a concrete catalogue of military force elements that would speed up the establishment of a force when the EU decides to launch an operation. It is land-focused and aims to generate a force of 60,000 troops from the contributing states alone. While it does not establish any form of "European army", it foresees an deployable, interoperable force under a single command.[76] Germany is the lead country for the project, but the French are heavily involved and it is tied to President Emmanuel Macron's proposal to create a standing intervention force. The French see it as an example of what PESCO is about.[77]

Provided through Article 42.3 TEU

This section presents an incomplete list of forces and bodies established intergovernmentally amongst a subset of member states. These organisations will deploy forces based on the collective agreement of their member states. They are typically technically listed as being able to be deployed under the auspices of NATO, the United Nations, the European Union (EU) through Article 42.3 of TEU, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, or any other international entity.

However, with the exception of the Eurocorps, very few have actually been deployed for any real military operation, and none under the CSDP at any point in its history.

Land Forces:

- The Eurocorps is an army corps of approximately 1,000 soldiers stationed in Strasbourg, France. Based in the French city of Strasbourg, the corps is the nucleus of the Franco-German Brigade.[78]

- The I. German/Dutch Corps is a multinational formation consisting of units from the Dutch and German armies. Due to its role as a NATO High Readiness Forces Headquarters, soldiers from other NATO member states, the United States, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Italy, the United Kingdom amongst others, are also stationed at Münster.

- The Multinational Corps Northeast, a Danish-German-Polish multinational corps

- The European Gendarmerie Force, an intervention force with militarised police functions which specializes in crisis management.

Aerial:

- The European Air Transport Command exercises operational control of the majority of the aerial refueling capabilities and military transport fleets of its participating nations. Located at Eindhoven Airbase in the Netherlands, the command also bears a limited responsibility for exercises, aircrew training and the harmonisation of relevant national air transport regulations.[79][80] The command was established in 2010 to provide a more efficient management of the participating nations' assets and resources in this field.

Naval:

- The European Maritime Force (EUROMARFOR or EMF) is a non-standing,[81] military force[82] that may carry out naval, air and amphibious operations, with an activation time of 5 days after an order is received.[83] The force was formed in 1995 to fulfill missions defined in the Petersberg Declaration, such as sea control, humanitarian missions, peacekeeping operations, crisis response operations, and peace enforcement.

Equipment

EU-developed infrastructure for military use includes:

Defence fund

The European Defence Fund is an EU-managed fund for coordinating and increasing national investment in defence research and improve interoperability between national forces. It was proposed in 2016 by President Jean-Claude Juncker and established in 2017 to a value of €5.5 billion per year. The fund has two stands; research (€90 million until the end of 2019 and €500 million per year after 2020) and development & acquisition (€500 million in total for 2019–20 then €1 billion per year after 2020).[84]

Together with the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence and Permanent Structured Cooperation it forms a new comprehensive defence package for the EU.[85]

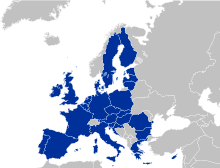

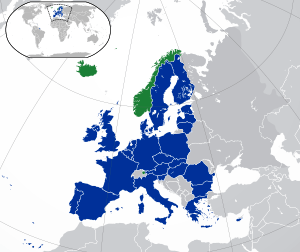

Participation, relationship with NATO

Out of the 28 EU member states, 22 are also members of NATO. Another three NATO members are EU applicants—Albania, Montenegro and Turkey. Two others—Iceland and Norway—have opted to remain outside of the EU, however participate in the EU's single market. The memberships of the EU and NATO are distinct, and some EU member states are traditionally neutral on defence issues. Several of the new EU member states were formerly members of the Warsaw Pact.

European Union |

Common Security and Defence Policy |

European Defence Agency |

Permanent Structured Cooperation |

North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| No | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial | |

| No | Partial (non-voting) | Partial (non-voting) | No | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| No | No | Partial (non-voting) | No | No | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial | |

| No | No | Partial (non-voting) | No | No | No | |

| No | No | No | No | Yes | Partial | |

| No | No | Partial (non-voting) | No | No | No | |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | |

| No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

The Berlin Plus agreement is the short title of a comprehensive package of agreements made between NATO and the EU on 16 December 2002.[86] These agreements were based on conclusions of NATO's 1999 Washington summit, sometimes referred to as the CJTF mechanism,[87] and allowed the EU to draw on some of NATO's military assets in its own peacekeeping operations.

See also

- European Union as an emerging superpower

- European countries by military expenditure as a percentage of government expenditure

- Neutral country#European Union

Other defence-related EU initiatives:

- Military Mobility (PESCO)

- European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE), an EU-supported intergovernmental think-tank

Other Pan-European defence organisations (intergovernmental):

- Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation (OCCAR)

- Finabel, an organisation, controlled by the army chiefs of staff of its participating nations, that promotes cooperation and interoperability between the armies.[88]

- Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation (OCCAR), an organisation that facilitates and manages collaborative armament programmes through their lifecycle between its participating nations.

- European Air Group (EAG), an organisation that promotes cooperation and interoperability between the air forces of its participating nations.

- European Organisation of Military Associations (EUROMIL)

- European Personnel Recovery Centre (EPRC), an organisation that contributes to the development and harmonisation of policies and standards related to personnel recovery.

- European Intervention Initiative

Regional, integorvernmental defence organisations in Europe:

- Nordic Defence Cooperation (NORDEFCO)

- Central European Defence Cooperation (CEDC)

Atlanticist intergovernmental defence organisations:

- North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO)

- Movement Coordination Centre Europe (MCCE), an organisation aiming to coordinate the use of airlift, sealift and land movement assets owned or leased by participating nations.

Notes

- ↑ The United Kingdom does not participate in the Permanent Structured Cooperation.

- ↑ The Edinburgh Agreement of 1992 included a guarantee to Denmark that they would not be obliged to join the Western European Union, which was responsible for defence. Additionally, the agreement stipulated that Denmark would not take part in discussions or be bound by decisions of the EU with defence implications. The Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997 included a protocol which formalised this opt-out from the EU's Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). As a consequence, Denmark is excluded from foreign policy discussions with defence implications and does not participate in foreign missions with a defence component.[1] Denmark does not participate in the Permanent Structured Cooperation. See Opt-outs_in_the_European_Union#Defence_–_Denmark.

- ↑ Malta does not participate in the Permanent Structured Cooperation.

- ↑ The responsibility of collective selv-defence within the CSDP is based on Article 42.7 of TEU, which states that this responsibility does not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain member states, referring to policies of nautrality. See Neutral country§European Union for discussion on this subject.According to the Article 42.7 "If a Member State is the victim of armed aggression on its territory, the other Member States shall have towards it an obligation of aid and assistance by all the means in their power, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. This shall not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of certain Member States." Article 42.2 furthermore specifies that NATO shall be the main forum for the implementation of collective self-defence for EU member states that are also NATO members.

- ↑ Akin to the EU’s banking union, economic and monetary union and customs union.

- ^ a b Spain withdrew last classic aircraft carrier Príncipe de Asturias in 2013 (currently in reserve). New universal ship of Juan Carlos I has the function of fleet carrier and amphibious assault ship.

References

- ↑ "EU - The Danish Defence Opt-Out". Danish Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Defence Data Portal, Official 2012 defence statistics from the European Defence Agency

- ↑ "Texts adopted - Tuesday, 22 November 2016 - European Defence Union - P8_TA(2016)0435". www.europarl.europa.eu.

- ↑ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - European Commission welcomes first operational steps towards a European Defence Union *". europa.eu.

- ↑ http://eppgroup.eu/document/119334

- ↑ "Glossary of summaries - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu.

- ↑ "EU to spend €1.5bn a year on joint defence".

- ↑ You want know more about the mission and receive news ? Bruxelles2.eu and Le Club

- ↑ Christopher S. Chivvis, "Birthing Athena. The Uncertain Future of ESDP" Archived 2008-06-27 at the Wayback Machine., Focus stratégique, Paris, Ifri, March 2008.

- ↑ "EUFOR Tchad/RCA" consilium.europa.eu

- ↑ Benjamin Pohl (2013) The logic underpinning EU crisis management operations Archived 2014-12-14 at the Wayback Machine., European Security, 22(3): 307–325, DOI:10.1080/09662839.2012.726220, p. 311.

- ↑ http://www.ifp-ew.eu/resources/EU_Concept_for_ESDP_support_to_Security_Sector_Reform.pdf

- ↑ Filip Ejdus, ‘Here is your mission, now own it!’ the rhetoric and practice of local ownership in EU interventions’, European Security, published online 6 June 2017 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09662839.2017.1333495

- ↑ "Treaty of Lisbon". EU. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Article 42, Treaty on European Union

- ↑ https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/impetus_24_dp_final_1.pdf

- ↑ Gatti, Mauro (2016). European External Action Service : Promoting Coherence through Autonomy and Coordination. Leiden: Brill. p. 148. ISBN 9789004323612. OCLC 951833456.

- ↑ Art. 5 of COUNCIL DECISION establishing the organisation and functioning of the European External Action Service PDF, Council of the European Union, 20 July 2010

- ↑ "The Crisis Management and Planning Directorate (CMPD)".

- ↑ "The Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC)".

- ↑ "The European Union Military Staff (EUMS)".

- ↑ "EU military HQ to take charge of Africa missions".

- ↑ "EU defence cooperation: Council establishes a Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC) - Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu.

- ↑ "Permanent Structured Cooperation: An Institutional Pathway for European Defence « CSS Blog Network". isnblog.ethz.ch.

- ↑ SCADPlus: European Security and Defence College (ESDC) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., Retrieved on 4 March 2008

- ↑ Sylvain, Paile, (1 September 2011). "Europe for the Future Officers, Officers for the Future Europe - Compendium of the European Military Officers Basic Education".

- ↑ France-Diplomatie: The main bodies specific to the CFSP: The Political and Security Committee, accessed on 21 April 2008

- ↑ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - High Representative Catherine Ashton appoints new Chair of the Political and Security Committee, a new Head of Delegation/EU Special Representative to Afghanistan, and new Heads of Delegation to Mauritania and Sierra Leone". europa.eu.

- ↑ The Council of the European Union: ESDP Structures, accessed on 21 April 2008

- ↑ "Preparatory document related to CESDP: Establishment of a European Union committee for civilian crisis management (Press Release: Brussels 10/3/2000)" (PDF).

- ↑ "Politico-Military Group (PMG) - Consilium". www.consilium.europa.eu.

- ↑ "EU Operations Centre".

- ↑ https://www.difesa.it/SMD_/COI/ITAJFHQ/Documents/brochureENG.pdf

- ↑ https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/20180423_ceumc_opening_remarks_at_dvd_milex_18.pdf

- ↑ http://www.eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/csdp/structures-instruments-agencies/eu-operations-centre/docs/factsheet_eu_opcen_23_06_2015.pdf

- ↑ Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) - Factsheet, European External Action Service

- 1 2 http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/32079/pesco-overview-of-first-collaborative-of-projects-for-press.pdf

- ↑ (Stratégie globale de l'Union européenne, p. 1)

- ↑ (Conclusions du Conseil du 14 novembre 2016)

- ↑ https://www.eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/documents/eda-defence-data-2006-2016

- ↑ "USAF Report: "Most" Nuclear Weapon Sites In Europe Do Not Meet US Security Requirements » FAS Strategic Security Blog". 10 March 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 EU-US Defence Data 2011, European Defence Agency, September 2013

- ↑ Croft, Adrian (19 September 2012). "Some EU states may no longer afford air forces-general". Reuters. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ↑ Todd, Daniel; Lindberg, Michael (1996). Navies and Shipbuilding Industries: The Strained Symbiosis. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 56–57. ISBN 9780275953102

- ↑ Marinecomponent Hoofdpagina. Mil.be. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Jane's Fighting Ships 2009

- ↑ (in German) Offizieller Internetauftritt der Marine. www.marine.de. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Πολεμικό Ναυτικό – Επίσημη Ιστοσελίδα. Hellenicnavy.gr. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Home | Defence Forces. Military.ie. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Marina Militare. Marina.difesa.it. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ (in Lithuanian) Lithuanian Armed Forces :: Structure » Navy. Kariuomene.kam.lt (21 January 2010). Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ AFM - MARITIME PATROL VESSELS. Afm.gov.mt. Retrieved on 2015-04-08.

- ↑ Koninklijke Marine | Ministerie van Defensie. Defensie.nl. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ (in Polish) Marynarka Wojenna. Mw.mil.pl. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Marinha Portuguesa Archived 22 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.. Marinha.pt. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ (in Romanian) Fortele Navale Române. Navy.ro. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Slovensko obalo bo varovala "Kresnica" :: Prvi interaktivni multimedijski portal, MMC RTV Slovenija. Rtvslo.si. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Presentación Buques de Superficie – Ships – Armada Española. Armada.mde.es. Retrieved on 2018-09-07.

- ↑ The Swedish Navy – Försvarsmakten Archived 18 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Forsvarsmakten.se (2 September 2008). Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- ↑ Home. Royal Navy. Retrieved on 2011-12-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Ministry of Defence - Vehicle & Aircraft Holdings within the scope of the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty: Annual: 2013 edition, gov.uk, (pp.10-13), Accessed 28 November 2014

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ↑

- ↑ [Irish Defence Forces http://www.military.ie/en/army/organisation/army-corps/artillery/]

- ↑

- ↑ http://washington.mfa.gov.pl/en/about_the_embassy/waszyngton_us_a_en_embassy/waszyngton_us_a_en_military_attach/waszyngton_us_a_109

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 World Air Force 2014 - Flight International, Flightglobal.com, Accessed 23 November 2014

- ↑ "RAF – A400m." Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. RAF, MOD. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

- ↑ http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/Battlegroups.pdf

- 1 2 New force behind EU foreign policy BBC News – 15 March 2007

- ↑ "Europe in a foreign field".

- ↑ Value of EU 'Battlegroup' plan stressed by Annan Archived 13 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. forumoneurope.ie 15 October 2004

- ↑ "In Defence of Europe - EPSC - European Commission". EPSC.

- ↑ "Project outlines" (PDF).

- ↑ "European Defence: What's in the CARDs for PESCO?" (PDF).

- ↑ Barigazzi, Jacopo (10 December 2017). "EU unveils military pact projects". Politico. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ "Eurocorps' official website / History". Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ↑ Eindhoven regelt internationale militaire luchtvaart (in Dutch)

- ↑ "Claude-France Arnould Visits EATC Headquarters". Eda.europa.eu. Retrieved 2016-02-19.

- ↑ EUROMARFOR – At Sea for Peace pamphlet. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ Biscop, Sven (2003). Euro-Mediterranean security: a search for partnership. Ashgate Publishing. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7546-3487-4.

- ↑ EUROMARFOR Retrospective – Portuguese Command, page 12. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ "European Commission - PRESS RELEASES - Press release - A European Defence Fund: €5.5 billion per year to boost Europe's defence capabilities". europa.eu.

- ↑ Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) – Factsheet, European External Action Service

- ↑ NATO, Berlin Plus agreement, 21 June 2006."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-08-17. Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ↑ Heritage Foundation report, 4 October 2004 : "Through the CJTF mechanism, NATO member states do not have to actively participate actively in a specific mission if they do not feel their vital interests are involved, but their opting out [...] would not stop other NATO members from participating in an intervention if they so desired." Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Finabel information folder: "Finabel: Contributing to European Army Interoperability since 1953" Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- Book – What ambitions for European defence in 2020?, European Union Institute for Security Studies

- Book – European Security and Defence Policy: The first 10 years (1999–2009), European Union Institute for Security Studies

- "Guide to the ESDP" nov.2008 edition Exhaustive guide on ESDP's missions, institutions and operations, written and edited by the Permanent representation of France to the European Union.

- Dijkstra, Hylke (2013). Policy-Making in EU Security and Defense: An Institutional Perspective. European Administrative Governance Series (Hardback 240pp ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. ISBN 978-1-137-35786-1.

- Nugent, Neill (2006). The Government and Politics of the European Union. The European Union Series (Paperback 630pp ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, New York. ISBN 9780230000025.

- Howorth, Joylon (2007). Security and Defence Policy in the European Union. The European Union Series (Paperback 315pp ed.). Palgrave Macmillan, New York. ISBN 978-0-333-63912-2.

- PhD Thesis on Civilian ESDP - EU Civilian crisis management (University of Geneva, 2008, 441 p. in French)

- Hayes, Ben (2009). NeoConOpticon: The EU Security-Industrial Complex (Paperback, 84 pp ed.). Transnational Institute/Statewatch. ISSN 1756-851X.

- Giovanni Arcudi & Michael E. Smith (2013). The European Gendarmerie Force: a solution in search of problems?, European Security, 22(1): 1–20, DOI:10.1080/09662839.2012.747511

- Teresa Eder (2014). Welche Befugnisse hat die Europäische Gendarmerietruppe?, Der Standard, 5 Februar 2014.

- Alexander Mattelaer (2008). The Strategic Planning of EU Military Operations – The Case of EUFOR Tchad/RCA, IES Working Paper 5/2008.

- Benjamin Pohl (2013). The logic underpinning EU crisis management operations, European Security, 22(3): 307–325, DOI:10.1080/09662839.2012.726220

- "The Russo-Georgian War and Beyond: towards a European Great Power Concert", Danish Institute of International Studies.

- U.S Army Strategic Studies Institute (SSI), Operation EUFOR TCHAD/RCA and the EU's Common Security and Defense Policy., U.S. Army War College, October 2010

- Mai'a K. Davis Cross "Security Integration in Europe: How Knowledge-based Networks are Transforming the European Union." University of Michigan Press, 2011.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Military of the European Union. |

- Official website, European External Action Service

- Security and Defence, European External Action Service

- EU cooperation on security and defence, Council of the European Union

._Arrivals_Esa_Pulkkinen_(36890876876)_(cropped).jpg)