Kamarupa

Kamarupa (/ˈkɑːməˌruːpə/; also called Pragjyotisha or Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa), an early state[6] during the Classical period on the Indian subcontinent was (along with Davaka) the first historical kingdom of Assam.[7]

Kamarupa Kingdom | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 350–1140 | |||||||||||||||

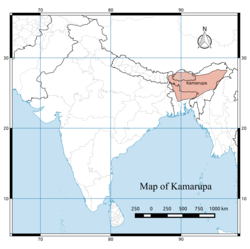

The 7th and 8th century extent of Kamarupa kingdom, located on the eastern region of the Indian subcontinent, what is today modern-day Assam, Bengal and Bhutan.[1] Kamarupa at its height covered the entire Brahmaputra Valley, North Bengal, Bhutan and northern part of Bangladesh, and at times portions of West Bengal and Bihar.[2] | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Pragjyotishpura Haruppeswara Durjaya | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kamarupi Prakrit, Sanskrit, Austroasiatic, Tibeto-Burman[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy[4] | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical India | ||||||||||||||

• Established | 350 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1140 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India Bhutan Bangladesh Nepal | ||||||||||||||

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Palaeolithic (2,500,000–250,000 BC) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Neolithic (10,800–3300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chalcolithic (3500–1500 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – AD 1206) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1526)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial states (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Periods of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

National histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Specialised histories

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Kamarupa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ruling dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Varman dynasty (350–650 CE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mlechchha dynasty (650–900 CE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pala Dynasty (900–1100 CE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Assam |

|---|

|

|

Proto-historic |

|

Late Medieval |

|

Modern |

|

Contemporary |

| Categories |

|

Though Kamarupa existed from 350 CE to 1140 CE, Davaka was absorbed by Kamarupa in the 5th century CE.[8][9] Ruled by three dynasties from their capitals in present-day Guwahati, North Guwahati and Tezpur, Kamarupa at its height covered the entire Brahmaputra Valley, North Bengal,[10] Bhutan and northern part of Bangladesh, and at times portions of what is now West Bengal and Bihar.[2]

Though the historical kingdom disappeared by the 12th century to be replaced by smaller political entities, the notion of Kamarupa persisted and ancient and medieval chroniclers continued to call this region by this name.[11] In the 16th century the Ahom kingdom came into prominence and assumed for itself the political and territorial legacy of the Kamarupa kingdom.[12]

Etymology

Pragjyotisha seems to have been the name of the city and the adjoining areas (city-state) while Kamarupa came to be the name of the country later and used synonymously.[13] The earliest use of the name Kamarupa to denote the kingdom is from the 4th-century.[14] The 10th-century Kalika Purana mentioned that country got its name from Kamadeva (Kama), who regain his form (Rupa) back from ashes here.[15]

Antecedents

Kamarupa is not included in the list of sixteen Mahajanapadas from the sixth to fourth centuries BCE;[16] nor does it or the northeast Indian region find any mention in the Ashokan records (3rd century BCE)[17]—it was not part of the Mauryan Empire.[18] The 3rd-2nd century BCE Baudhayana Dharmasutra mentions Anga (eastern Bihar), Magadha (southern Bihar), Pundra (northern Bengal) and Vanga (southern Bengal), and that a Brahmana required purification after visiting these places[19]—but it does not mention Kamarupa, thereby indicating it was beyond the ambit and recognition of the Brahminical culture in the second half of the first millennium BCE.[20]

The first dated mention comes from the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century) where it describes a people called Sêsatea,[21] and the second mention comes from Ptolemy's Geographia (2nd century) which calls the region Kirrhadia after the Kirata population.[22] Arthashastra (early centuries of the Christian era[23]) mentions "Lauhitya",[24] which is identified with Brahmaptra valley by a later commentator.[25] These early references speak about the economic activity of a tribal belt, and have nothing to say about their kingdoms.[26]

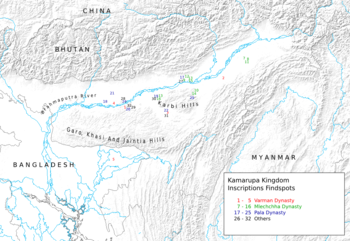

The earliest mention of a kingdom comes from the 4th-century Allahabad inscription of Samudragupta that calls the kings of Kamarupa and Davaka frontier rulers (pratyanta nripati).[27] The Chinese traveler Xuanzang visited the kingdom in the 7th century, then ruled by Bhaskaravarman.[28] The corpus of Kamarupa inscriptions left by the rulers of Kamarupa, including Bhaskaravarman, at various places in Assam and present-day Bangladesh are important sources of information. Nevertheless, local grants completely eschew the name Kamarupa; instead they use the name Pragjyotisha, with the kings called Pragjyotishadhipati.[29]

Boundaries

The kingdom in the fourth century was small but soon engulfed the entire Brahmaputra valley and beyond.[30] According to the 10th century Kalika Purana and the 7th century Xuanzang, the western boundary was the historical Karatoya River. The eastern border was the temple of the goddess Tamreshvari (Pūrvāte Kāmarūpasya devī Dikkaravasini, given in Kalika Purana) near present-day Sadiya.[31][32] The southern boundary was near the border between the Dhaka and Mymensingh districts in Bangladesh. Thus it spanned the entire Brahmaputra valley and Northeast India and at various times included parts of present-day Bhutan, Bangladesh and Nepal.[33] This is supported by the various epigraphic records found scattered over these regions.[1] The kingdom appears to have broken up entirely by the 13th century into smaller kingdoms and from among them rose the Kamata kingdom in the west and the Ahom, Dimasa and the Chutiya kingdoms as the main successors, with the Baro-Bhuyans ruling intervening areas.

State

The extent of state structures can be culled from the numerous Kamarupa inscriptions left behind by the Kamarupa kings as well as accounts left by travellers such as those from Xuanzang.[34] Governance followed the classical saptanga structure of state.[35]

Kings and courts: The king was considered to be of divine origin. Succession was primogeniture, but two major breaks resulted in different dynasties. In the second, the high officials of the state elected a king, Brahmapala, after the previous king died without leaving an heir. The royal court consisted of a Rajaguru, poets, learned men and physicians. Different epigraphic records mention different officials of the palace: Mahavaradhipati, Mahapratihara, Mahallakapraudhika, etc.

Council of Ministers: The king was advised by a council of ministers (Mantriparisada), and Xuanzang mentions a meeting Bhaskaravarman had with his ministers. According to the Kamauli grant, these positions were filled by Brahmanas and were hereditary. State functions were specialized and there were different groups of officers looking after different departments.

Revenue: Land revenue (kara) was collected by special tax-collectors from cultivators. Cultivators who had no proprietary rights on the lands they tilled paid uparikara. Duties (sulka) were collected by toll collectors (Kaivarta) from merchants who plied keeled boats. The state maintained a monopoly on copper mines (kamalakara). The state maintained its stores and treasury via officials: Bhandagaradhikrita and Koshthagarika.

Grants: The king occasionally gave Brahmanas grants (brahmadeya), which consisted generally of villages, water resources, wastelands etc. (agraharas). Such grants conferred on the donee the right to collect revenue and the right to be free of any regular tax himself and immunity from other harassments. Sometimes, the Brahmanas were relocated from North India, with a view to establish varnashramdharma. Nevertheless, the existence of donees indicate the existence of a feudal class. Grants made to temples and religious institutions were called dharmottara and devottara respectively.

Land survey: The land was surveyed and classified. Arable lands (kshetra) were held individually or by families, whereas wastelands (khila) and forests were held collectively. There were lands called bhucchidranyaya that were left unsurveyed by the state on which no tax was levied.

Administration: The entire kingdom was divided into a hierarchy of administrative divisions. From the highest to the lowest, they were bhukti, mandala, vishaya, pura (towns), agrahara (collection of villages) and grama (village). These units were administered by headed by rajanya, rajavallabha, vishayapati etc.[35] Some other offices were nyayakaranika, vyavaharika, kayastha etc., led by the adhikara. They dispensed judicial duties too, though the ultimate authority lay with the king. Law enforcement and punishments were made by officers called dandika, (magistrate) and dandapashika (one who executed the orders of a dandika).

Political history

Kamarupa, first mentioned on Samudragupta's Allahabad rock pillar as a frontier kingdom, began as a subordinate but sovereign ally of the Gupta empire around present-day Guwahati in the 4th century.[36] It finds mention along with Davaka, a kingdom to the east of Kamarupa in the Kapili river valley in present-day Nagaon district, but which is never mentioned again as an independent political entity in later historical records. Kamarupa, which was probably one among many such state structures, grew territorially to encompass the entire Brahmaputra valley and beyond. The kingdom was ruled by three major dynasties, all of which drew their lineage from the legendary aboriginal king Naraka, who is said to have established his line by defeating another aboriginal king Ghatakasura of the Danava dynasty.

Varman dynasty (c. 350 – c. 650)

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Assam |

|---|

|

|

Proto-historic

Classical Medieval

Modern |

|

|

|

Festivals

|

|

Religion Major

Others |

|

History

Archives

Genres

Institutions Awards |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media |

|

Symbols

|

Pushyavarman (350–374) established the Varman Dynasty, by fighting many enemies from within and without his kingdom; but his son Samudravarman (374–398), named after Samudragupta, was accepted as an overlord by many local rulers.[40] Nevertheless, subsequent kings continued their attempts to stabilise and expand the kingdom.[41] The Nagajari Khanikargaon rock inscription of 5th century found in Sarupathar in Golaghat district of Assam adduces the fact that the kingdom spread to the east very quickly. Kalyanavarman (422–446) occupied Davaka and Mahendravarman (470–494) further eastern areas.[8] Narayanavarma (494–518) and his son Bhutivarman (518–542) offered the ashwamedha (horse sacrifice);[42] and as the Nidhanpur inscription of Bhaskarvarman avers, these expansions included the region of Chandrapuri visaya, identified with present-day Sylhet division. Thus, the small but powerful kingdom that Pushyavarman established grew in fits and starts over many generations of kings and expanded to include adjoining possibly smaller kingdoms and parts of Bangladesh.

After the initial expansion till the beginning of Bhutivarman's reign, the kingdom came under attack from Yasodharman (525–535) of Malwa, the first major assault from the west.[43] Though it is unclear what the effect of this invasion was on the kingdom; that Bhutivarman's grandson, Sthitavarman (566–590), enjoyed victories over the Gauda of Karnasuvarna and performed two aswamedha ceremonies suggests that the Kamarupa kingdom had recovered nearly in full. His son, Susthitavarman (590–600) came under the attack of Mahasenagupta of East Malwa. These back and forth invasions were a result of a system of alliances that pitted the Kamarupa kings (allied to the Maukharis) against the Gaur kings of Bengal (allied with the East Malwa kings).[44] Susthitavarman died as the Gaur invasion was on, and his two sons, Suprathisthitavarman and Bhaskarvarman fought against an elephant force and were captured and taken to Gaur. They were able to regain their kingdom due probably to a promise of allegiance.[45] Suprathisthitavarman's reign is given as 595–600, a very short period, at the end of which he died without an heir.

Supratisthitavarman was succeeded by his brother, Bhaskarvarman (600–650), the most illustrious of the Varman kings who succeeded in turning his kingdom and invading the very kingdom that had taken him captive. Bhaskarvarman had become strong enough to offer his alliance with Harshavardhana just as the Thanesar king ascended the throne in 606 after the murder of his brother, the previous king, by Shashanka of Gaur. Harshavardhana finally took control over the kingless Maukhari kingdom and moved his capital to Kanauj.[46] The alliance between Harshavardhana and Bhaskarvarman squeezed Shashanka from either side and reduced his kingdom, though it is unclear whether this alliance resulted in his complete defeat. Nevertheless, Bhaskarvarman did issue the Nidhanpur copper-plate inscription from his victory camp in the Gaur capital Karnasuvarna (present-day Murshidabad, West Bengal) to replace a grant issued earlier by Bhutivarman for a settlement in the Sylhet region of present-day Bangladesh.[47]

Mlechchha dynasty (c. 655 – c. 900 CE)

After Bhaskaravarman's death without an heir, the kingdom passed into the hands of Salasthambha (655–670), an erstwhile local governor[48] and a member of an aboriginal group called Mlechchha (or Mech), after a period of civil and political strife. This dynasty too drew its lineage from the Naraka dynasty, though it had no dynastic relationship with the previous Varman dynasty. The capital of this dynasty was Haruppeshvara, now identified with modern Dah Parbatiya near Tezpur. The kingdom took on feudal characteristics[49] with political power shared between the king and second and third tier rulers called mahasamanta and samanta who enjoyed considerable autonomy.[50] The last ruler in this line was Tyāga Singha (890–900).

Pala dynasty (c. 900 – c. 1100)

After the death of Tyāgasimha without an heir, a member of the Bhauma family, Brahmapala (900–920), was elected as king by the ruling chieftains, just as Gopala of the Pala Empire of Bengal was elected. The original capital of this dynasty was Hadapeshvara, and was shifted to Durjaya built by Ratnapala (920–960), near modern Guwahati. The greatest of the Pala kings, Dharmapala (1035–1060) had his capital at Kamarupanagara, now identified with North Guwahati. The last Pala king was Jayapala (1075–1100). Around this time, Kamarupa was attacked and the western portion was conquered by the Pala king Ramapala.

Breakup and End of Kamarupa

Western Kamarupa

Ramapala could not keep control for long, and Timgyadeva (1110–1126) ruled western Kamarupa independently for some time. His son Kumarapala sent Vaidyadeva against Timgyadeva who installed himself at Hamshkonchi in the Kamrup region. Though Vaidyadeva maintained friendly relationships with Kumarapala, he styled himself after the Kamarupa kings issuing grants under the elephant seal of erstwhile Kamarupa kings and assuming the title of Maharajadhiraja, though he did not call himself Pragjyotisadhipati like the Kamarupa kings did. He controlled a portion of Kamrup, Goalpara and North Bengal but not Kamarupanagara, the seat of the last Kamarupa kings.[51]

Central Kamarupa

It is estimated that with the withering away of the Kamarupa kingdom, parts of Kamrup, Darrang and Sonitpur districts on the north bank of the Brahmaputra river came under the control of one Bhaskara.[52] A single inscription (1185) gives a list of four rulers that have been called the Lunar dynasty—Bhaskara, Rayarideva, Udayakarna and Vallabhadeva—with their reign dated to 1120–1200.[53]

Southern Kamarupa

In the Sylhet region, there emerged rulers called Kharabana, Gokuladeva, Narayana and Kesavadeva.[54]

Kamarupa Proper

Kamarupa proper was confined to the south bank of Brahmaputra, with the power center still at Kamarupanagara,[55] with three rulers associated with it: Prithu, Samudrapala and Sandhya.[56]

In 1206 the Afghan Muhammad-i-Bakhtiyar passed through Kamarupa against Tibet which ended in disaster, the first of many Turko-Afghan invasions. The ruler of Kamarupa at this point was Prithu (d. 1228, called Britu in Tabaqat-i Nasiri), who is sometimes identified with Visvasundara, the son of Vallabhadeva of the Lunar dynasty, mentioned in the Gachtal inscription of 1232 A.D.[57] Prithu withstood invasions (1226–27) from Ghiyasuddin Iwaj Shah of Gauda who retreated, but was killed in the subsequent invasion by Nasiruddin Mahmud in 1228.[58] Nasir-ud-din installed a tributary king but after his death in 1229 the control of Kamarupa lapsed back to local rulers.[59]

Beginning of Kamata

From among the local rulers, there emerged a strong ruler named Sandhya (c.1250–1270), the Rai of Kamrup, with his capital at Kamarupanagara, the seat of the last Pala kings. Malik Ikhtiyaruddin Iuzbak, a governor of Gaur for the Mamluk rulers of Delhi, attempted an invasive attack on Sandhya's domain in 1257; and Sandhya, with the help of the spring floods that same year, captured and killed the Sultan.[60] Subsequent to this attack, Sandhya moved his capital from Kamarupanagara to Kamatapur (North Bengal) and established a new kingdom, that came to be called Kamata.[61]

At that time, western Kamarupa was the domain of the Koch and Mech peoples.[62] In other parts of the erstwhile Kamarupa the Kachari kingdom (central Assam, South bank), Baro Bhuyans (central Assam, North bank), and the Chutiya kingdom (east) were emerging. The Ahoms, who would establish a strong and independent kingdom later, began building their state structures in the region between the Kachari and the Chutiya kingdoms in 1228.

See also

- Kamata kingdom

- Kamrup (disambiguation)

- History of Assam

Notes

- (Dutta 2008:281), reproduced from (Acharya 1968).

- Sircar (1990a), pp. 63–68.

- "... (it shows) that in Ancient Assam there were three languages viz. (1) Sanskrit as the official language and the language of the learned few, (2) Non-Aryan tribal languages of the Austric and Tibeto-Burman families, and (3) a local variety of Prakrit (ie a MIA) wherefrom, in course of time, the modern Assamese language as a MIL, emerged." (Sharma 1978, pp. 0.24-0.28)

- "The government of Kamarupa state was absolute monarchy in nature with the king at the top of the political structure." (Boruah 2005:1465)

- Lahiri (1991), pp. 26–28.

- "Pragjyotisa-Kamarupa had emerged as an 'early state' by covering a large part of present north-east India, part of neighbouring west-Bengal and Bangladesh in the period between the 4th to the 12th century." (Boruah 2005:1464)

- Suresh Kant Sharma, Usha Sharma - 2005,"Discovery of North-East India: Geography, History, Culture, ... - Volume 3", Page 248, Davaka (Nowgong) and Kamarupa as separate and submissive friendly kingdoms.

- "As regards the eastern limits of the kingdom, Davaka was absorbed within Kamarupa under Kalyanavarman and the outlying regions were brought under subjugation by Mahendravarman." (Choudhury 1959, p. 47)

- "It is presumed that (Kalyanavarman) conquered Davaka, incorporating it within the kingdom of Kamarupa" (Puri 1968, p. 11)

- "According to the Kalika Purana and the Yogonitantra, the ancient Kamarupa included, besides the districts of modern Assam, Cooch-Behar, Rang-pura, Jalpaiguri and Dinajpur within its territory." (Saikia 1997, p. 3)

- In the medieval times the region between the Sankosh river and the Barnadi river on the northern bank of the Brahmaputra river was defined as Kamrup (or Koch Hajo in Persian chronicles)(Sarkar 1990:95)

- "They also looked upon themselves as the heirs of the glory that was ancient Kamarupa by right of conquest, and they long cherished infructuously their unfulfilled hopes of expanding up to that frontier." (Guha 1983:24). 'An Ahom force reached the banks of the Karatoya in hot pursuit of an invading Turko-Afghan army in the 1530s. Since then "the washing of the sword in the Karatoya" became a symbol of the Assamese aspirations, repeatedly evoked in the Bar-Mels and mentioned in the chronicles." (Guha 1983:33)

- "The earliest name of Assam is Pragjyotisha, i.e. the territory of around the city of that name, while Kamarupa, later used as the name of the country, (was a) synonym of Pragjyotisha." (Sircar 1990a:57)

- (Sirkar 1990a:57)

- Barua, Birinchi Kumar; Kakati, Banikanta (1969). A cultural history of Assam - Volume 1. p. 15.

- "Kamariipa was not included in the 16 Mahajanapadas during the time of the Buddha."(Shin 2018:28)

- (Puri 1968, p. 4)

- "(T)he north-eastern region was outside the Maurya Empire." (Shin 2018:28)

- "Angas, Magadhas, Pundras and Vangas are mentioned in the Baudhiiyana Dharmasiitra (1.2.14-6) dated to the period between the early third and mid-second centuries BCE. The Angas and Magadhas lived in eastern and southern Bihar respectively, and the Pundras and the Vangas in northern and southern Bengal, respectively. . It is prescribed that a brahmana must have purification by the performance of punastoma or sarvarishtha after visiting their places. (Shin 2018:28)

- (Shin 2018:28)

- Besatia in the Schoff translation and also sometimes used by Ptolemy, they are a people similar to Kirradai and they lived in the region between "Assam and Sichuan" (Casson 1989, pp. 241–243)

- "The Periplus of the Erythraen Sea (last quarter of the first century A.D) and Ptolemy's Geography (middle of the second century A.D) appear to call the land including Assam Kirrhadia after its Kirata population." (Sircar 1990:60–61)

- "...the Arthashastra in its present form has to be assigned to the early centuries of the Christian era and the commentaries to much later dates." (Sircar 1990, p. 61)

- Niśipada Caudhurī (1985), Historical archaeology of central Assam, p.2

- "If we go by Bhattaswamin's commentary on Arthashastra Magadha was already importing certain items of trade from this [Brahmaputra] Valley in Kautilya's days" (Guha 1984, p. 76)

- "Kautilya's Arthashastra, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, the Geography of Ptolemy and other early literary works only speak of economic pursuits of the tribal belt of the north-eastern region...but had nothing to say about their kingdoms." (Shin 2018, p. 28)

- (Sharma 1978, p. xv)

- Bhushan 2005, p. 21.

- "The name Kamarupa does not appear in local grants where Pragjyotisha alone figures with the local rulers called Pragjyotishadhipati." (Puri 1968, p. 3)

- Sailendra Nath Sen (1999), Ancient Indian History and Civilization, p.303 Kamarupa at that time did not comprise the whole of the Assam valley as Davaka mentioned along with Kamarupa in the Allahabad Inscription, has been located in modern Nowgong district.

- "...the temple of the goddess Tameshwari (Dikkaravasini) is now located at modern Sadiya about 100 miles to the northeast of Sibsagar" (Sircar 1990a:63–64)

- "(T)he kingdom is demarcated as in the East, the Dikkaravasini and the river Dikshu (identified with Tamreswari temple and river Dibang of the Sadiya region respectively)" (Boruah 2007:32)

- "(T)he kingdom of Kamarupa extended up to the river Karatoya in the west and included Manipur, Jaintiya, Cachar, parts of Mymensing, Sylhet, Rangpur and portions of Nepal and Bhutan." (Baruah 1995:75)

- Choudhury, P. C., (1959) The History of Civilization of the People of Assam, Guwahati

- Puri (1968), p. 56.

- "Royal history of Cooch Behar". coochbehar.nic.in. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "639 Identifier Documentation: aho – ISO 639-3". SIL International (formerly known as the Summer Institute of Linguistics). SIL International. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

Ahom [aho]

- "Population by Religious Communities". Census India – 2001. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

Census Data Finder/C Series/Population by Religious Communities

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- Lahiri (1991), p. 68.

- Lahiri (1991), p. 72.

- (Sircar 1990b:101)

- (Lahiri 1991:70). Though the first evidence is from the Mansador stone pillar inscription of Yasodharman, there is no reference to this invasion in the Kamarupa inscriptions.

- (Sircar 1990b:106–107)

- (Sircar 1990b:109)

- (Sircar 1990b:113)

- Sircar (1990b), p. 115.

- (Lahiri 1991:76)

- Lahiri (1991), pp. 77–79.

- Lahiri (1991), p. 78.

- (Boruah 2011:80)

- (Boruah 2011:81)

- (Sircar 1992:166)

- (Boruah 2011:81)

- " The original Pragjyotisa-Kamarupa kingdom, after Jayapala could continue its political hold over a small area on the south bank of the Brahmaputra with its power centre at Kamarupanagara." (Boruah 2011:82)

- (Boruah 2011:82)

- "Visvasundara (son and successor of Vallabhadeva), (?) was perhaps to be identified with Prithu or Bartu of Minhaj." (Sarkar 1992:37–38) (Note:11)

- (Sarkar 1992:38)

- "Notwithstanding the attempts by some of (Iuzbak's) daring predecessors to subjugate Kamarupa between Karatoya and Barnadi, it was still virtually a land unknown to the Sultans of Bengal, politically it was not unified but parceled among the Bodo, Koch and Mech Baro-Bhuyans, constituting a loose confederacy under the strongest of them." (Sarkar 1992:38)

- (Sarkar 1992, pp. 39–40)

- (Kamarupa) was reorganized as a new state, 'Kamata' by name with Kamatapur as capital. The exact time when the change was made is uncertain. But possibly it had been made by Sandhya (c. 1250 – 1270) as a safeguard against mounting dangers from the east and the west. Its control on the eastern regions beyond the Manah (Manas river) was lax."(Sarkar 1992, pp. 40–41)

- "The description of (Bakhtiyar Khalji's) disastrous campaign provides us with some information about the populations (Siraj 1881: 560-1):... Konch, sometimes written Koch, (the same hesitation occurs in Buchanan-Hamilton’s manuscripts), is what we today write as Koch. Mej or Meg is the name we write as Mech. We can safely conclude that these names described important groups of people in the 13th century, in the area between the Ganges and the Brahmaputra." (Jaquesson 2008:16-17)

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kamarupa Kingdom. |

- Acharya, N. N. (1968), Asama Aitihashik Bhuchitravali (Maps of Ancient Assam), Bina Library, Gauhati, AssamCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Baruah, S L (1995), A Comprehensive History of Assam, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt Ltd

- Boruah, Nirode (2005). "'Early State' Formation in the Brahmaputra Valley of Assam". Proceedings of the Indian Historical Congress. 66: 1464–1465. JSTOR 44145968.

- Boruah, Nirode (2011). "Kamarupa to Kamata: The political Transition and the New Geopolitical Trends and Spaces". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 72: 78–86. JSTOR 44146698.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boruah, Nirode (2007), Early Assam, Guwahati, Delhi: Spectrum Publications

- Casson, Lionel (1989). The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text With Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04060-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Choudhury, P. C. (1959), The History of Civilization of the People of Assam to the Twelfth Century AD, Department of History and Antiquarian Studies, Gauhati, AssamCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dutta, Anima (2008). Political geography of Pragjyotisa Kamarupa (PhD). Gauhati University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guha, Amalendu (December 1983), "The Ahom Political System: An Enquiry into the State Formation Process in Medieval Assam (1228–1714)" (PDF), Social Scientist, 11 (12): 3–34, doi:10.2307/3516963, JSTOR 3516963CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guha, Amalendu (1984). "Pre-Ahom Roots and the Medieval State in Assam: A Reply". Social Scientist. 12 (6): 70–77. doi:10.2307/3517005. JSTOR 3517005.

- Jacquesson, François (2008). "Discovering Boro-Garo" (PDF). History of an Analytical and Descriptive Linguistic Category: 21.

- Lahiri, Nayanjot (1991), Pre-Ahom Assam: Studies in the Inscriptions of Assam between the Fifth and the Thirteenth Centuries AD, Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt LtdCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Puri, Baij Nath (1968), Studies in Early History and Administration in Assam, Gauhati UniversityCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saikia, Nagen (1997). "Medieval Assamese Literature". In Ayyappa Panicker, K (ed.). Medieval Indian Literature: Assamese, Bengali and Dogri. 1. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. pp. 3–20.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarkar, J N (1990), "Koch Bihar, Kamrup and the Mughals, 1576–1613", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam: Mediebal Period, Political, II, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 92–103CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarkar, J. N. (1992), "Chapter II The Turko-Afghan Invasions", in Barpujari, H. K. (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, 2, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board, pp. 35–48

- Shin, Jae-Eun (2018), "Region Formed and Imagined: Reconsidering temporal, spatial and social context of Kamarupa", in Dzüvichü, Lipokmar; Baruah, Manjeet (eds.), Modern Practices in North East India: History, Culture, Representation, London & New York: Routledge, pp. 23–55CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sircar, D C (1990a), "Pragjyotisha-Kamarupa", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, I, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 59–78CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sircar, D C (1990b), "Political History", in Barpujari, H K (ed.), The Comprehensive History of Assam, I, Guwahati: Publication Board, Assam, pp. 94–171CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharma, Mukunda Madhava (1978), Inscriptions of Ancient Assam, Gauhati University, Assam