Economic history of India

The economic history of India begins with the Indus Valley Civilisation (3300–1300 BCE), whose economy appears to have depended significantly on trade and examples of overseas trade. The Vedic period saw countable units of precious metal being used for exchange. The term Nishka appears in this sense in the Rigveda.[1] Historically, India was the largest economy in the world for most of the next three millennia, starting around the 1st millennia BCE and ending around the beginning of British Raj.[2]

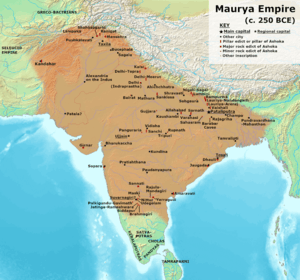

Around 600 BCE, the Mahajanapadas minted punch-marked silver coins. The period was marked by intensive trade activity and urban development. By 300 BCE, the Maurya Empire had united most of the Indian subcontinent. The resulting political unity and military security allowed for a common economic system and enhanced trade and commerce, with increased agricultural productivity.

The Maurya Empire was followed by classical and early medieval kingdoms, including the Cholas, Guptas, Western Gangas, Harsha, Palas, Rashtrakutas and Hoysalas. During this period, Between 1 CE and 1000 CE, the Indian subcontinent is estimated to have accounted for one-third, to one-fourth of the world's population, and product, though GDP per capita was stagnant. According to the Balance of Economic Power, India had the largest economy for most of the interval between the 1st century and 18th century, the most of any region for a large part of the last two millennia.[3] Up until 1000 CE, India had a large share of the world population, but its GDP per capita was not much higher than subsistence level.[4]

India experienced per-capita GDP growth in the high medieval era after 1000 CE, during the Delhi Sultanate in the north and Vijayanagara Empire in the south, but was not as productive as Ming China until the 16th century. By the late 17th century, most of the Indian subcontinent had been reunited under the Mughal Empire, which became the largest economy and manufacturing power in the world, producing about a quarter of global GDP, before fragmenting and being conquered over the next century.[5][6] During the medieval times, India was the world leader in manufacturing, producing 25% of the world's industrial output up until the mid-18th century, prior to British rule.[7][8] Bengal Subah, the empire's wealthiest province, that solely accounted for 40% of Dutch imports outside the west,[9] was a world leader in the productive agriculture, textile manufacturing and shipbuilding, and as its result, the proto-industrialization was emerged.[10][11][12]

By 18th century, Mysoreans embarked on an ambitious economic development program that established the Kingdom of Mysore as a major economic power, with some of the world's highest real wages and living standards in the late 18th century.[13] During this period, Mysore overtook the wealthy Bengal Subah as India's dominant economic power, with highly productive agriculture and textile manufacturing.[14] Mysore's average income was five times higher than subsistence level at the time.[15] The Maratha Empire also managed an effective administration and tax collection policy throughout the core areas under their control and extracted chauth from vassal states.[16]

India experienced deindustrialisation and cessation of various craft industries under British rule,[7] which along with fast economic and population growth in the Western World resulted in India's share of the world economy declining from 24.4% in 1700 to 4.2% in 1950,[17] and its share of global industrial output declining from 25% in 1750 to 2% in 1900.[7] Due to its ancient history as a trading zone and later its colonial status, colonial India remained economically integrated with the world, with high levels of trade, investment and migration.[18]

The Republic of India, founded in 1947, adopted central planning for most of its independent history, with extensive public ownership, regulation, red tape and trade barriers.[19][20] After the 1991 economic crisis, the central government launched economic liberalisation, allowing it to emerge as one of the world's fastest growing large economies.[19][21]

Indus Valley Civilization

.png)

Indus Valley Civilisation, the first known permanent and predominantly urban settlement, flourished between 3500 BCE and 1800 BCE. It featured an advanced and thriving economic system. Its citizens practised agriculture, domesticated animals, made sharp tools and weapons from copper, bronze and tin and traded with other cities.[22] Evidence of well-laid streets, layouts, drainage system and water supply in the valley's major cities, Dholavira, Harappa, Lothal, Mohenjo-daro and Rakhigarhi reveals their knowledge of urban planning.

Ancient and medieval characteristics

Although ancient India had a significant urban population, much of India's population resided in villages, whose economy was largely isolated and self-sustaining. Agriculture was the predominant occupation and satisfied a village's food requirements while providing raw materials for hand-based industries such as textile, food processing and crafts. Besides farmers, people worked as barbers, carpenters, doctors (Ayurvedic practitioners), goldsmiths and weavers.[23]

Religion

Religion played an influential role in shaping economic activities.

Pilgrimage towns like Prayagraj, Benares, Nasik and Puri, mostly centred around rivers, developed into centres of trade and commerce. Religious functions, festivals and the practice of taking a pilgrimage resulted in an early version of the hospitality industry.[24]

Economics in Jainism is influenced by Mahavira and his philosophy. He was the last of the 24 Tirthankars, who spread Jainism. Relating to economics he explained the importance of the concept of 'anekanta' (non-absolutism).[25]

Family business

In the joint family system, members of a family pooled their resources to maintain the family and invest in business ventures. The system ensured younger members were trained and employed and that older and disabled persons would be supported by their families. The system prevented agricultural land from splitting with each generation, aiding yield from the benefits of scale. Such sanctions curbed the spirit of rivality in junior members and instilled a sense of obedience.[26]

Organisational entities

.jpg)

Along with the family- and individually-owned businesses, ancient India possessed other forms of engaging in collective activity, including the gana, pani, puga, vrata, sangha, nigama and Shreni. Nigama, pani and Shreni refer most often to economic organisations of merchants, craftspeople and artisans, and perhaps even para-military entities. In particular, the Shreni shared many similarities with modern corporations, which were used in India from around the 8th century BCE until around the 10th century CE. The use of such entities in ancient India was widespread, including in virtually every kind of business, political and municipal activity.[28]

The Shreni was a separate legal entity that had the ability to hold property separately from its owners, construct its own rules for governing the behaviour of its members and for it to contract, sue and be sued in its own name. Ancient sources such as Laws of Manu VIII and Chanakya's Arthashastra provided rules for lawsuits between two or more Shreni and some sources make reference to a government official (Bhandagarika) who worked as an arbitrator for disputes amongst Shreni from at least the 6th century BCE onwards.[29] Between 18 and 150 Shreni at various times in ancient India covered both trading and craft activities. This level of specialisation is indicative of a developed economy in which the Shreni played a critical role. Some Shreni had over 1,000 members.

The Shreni had a considerable degree of centralised management. The headman of the Shreni represented the interests of the Shreni in the king's court and in many business matters. The headman could bind the Shreni in contracts, set work conditions, often received higher compensation and was the administrative authority. The headman was often selected via an election by the members of the Shreni, and could also be removed from power by the general assembly. The headman often ran the enterprise with two to five executive officers, also elected by the assembly.

Coinage

Punch marked silver ingots were in circulation around the 5th century BCE. They were the first metallic coins minted around the 6th century BCE by the Mahajanapadas of the Gangetic plains and were India's earliest traces of coinage. While India's many kingdoms and rulers issued coins, barter was still widely prevalent.[30] Villages paid a portion of their crops as revenue while its craftsmen received a stipend out of the crops for their services. Each village was mostly self-sufficient.[31]

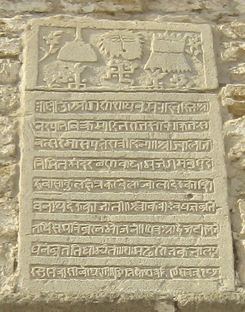

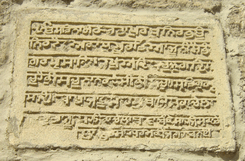

Maurya Empire

During the Maurya Empire (c. 321–185 BCE), important changes and developments affected the Indian economy. It was the first time most of India was unified under one ruler. With an empire in place, trade routes became more secure. The empire spent considerable resources building and maintaining roads. The improved infrastructure, combined with increased security, greater uniformity in measurements, and increasing usage of coins as currency, enhanced trade.[32]

West Coast

Maritime trade was carried out extensively between South India and Southeast and West Asia from early times until around the fourteenth century AD. Both the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts were the sites of important trading centres from as early as the first century BC, used for import and export as well as transit points between the Mediterranean region and southeast Asia.[33] Over time, traders organised themselves into associations which received state patronage. Historians Tapan Raychaudhuri and Irfan Habib claim this state patronage for overseas trade came to an end by the thirteenth century AD, when it was largely taken over by the local Parsi, Jewish, Syrian Christian and Muslim communities, initially on the Malabar and subsequently on the Coromandel coast.[34]

Silk Route

Other scholars suggest trading from India to West Asia and Eastern Europe was active between the 14th and 18th centuries.[35][36][37] During this period, Indian traders settled in Surakhani, a suburb of greater Baku, Azerbaijan. These traders built a Hindu temple, which suggests commerce was active and prosperous for Indians by the 17th century.[38][39][40][41]

Further north, the Saurashtra and Bengal coasts played an important role in maritime trade, and the Gangetic plains and the Indus valley housed several centres of river-borne commerce. Most overland trade was carried out via the Khyber Pass connecting the Punjab region with Afghanistan and onward to the Middle East and Central Asia.[42] Although many kingdoms and rulers issued coins, barter was prevalent. Villages paid a portion of their agricultural produce as revenue to the rulers, while their craftsmen received a part of the crops at harvest time for their services.[43]

Delhi Sultanate

Before and during the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 CE), Islam underlay a cosmopolitan civilization. It offered wide-ranging international networks, including social and economic networks. They spanned large parts of Afro-Eurasia, leading to escalating circulation of goods, peoples, technologies and ideas. While initially disruptive, the Delhi Sultanate was responsible for integrating the Indian subcontinent into a growing world system.[44]

The period coincided with a greater use of mechanical technology in the Indian subcontinent. From the 13th century onwards, India began widely adopting mechanical technologies from the Islamic world, including water-raising wheels with gears and pulleys, machines with cams and cranks,[45] papermaking technology,[46] and the spinning wheel.[47] The worm gear roller cotton gin was invented in the Indian subcontinent during the 13th–14th centuries,[48] and is still used in India through to the present day.[49] The incorporation of the crank handle in the cotton gin first appeared in the Indian subcontinent some time during the late Delhi Sultanate or the early Mughal Empire.[50] The production of cotton, which may have largely been spun in the villages and then taken to towns in the form of yarn to be woven into cloth textiles, was advanced by the diffusion of the spinning wheel across India during the Delhi Sultanate era, lowering the costs of yarn and helping to increase demand for cotton. The diffusion of the spinning wheel, and the incorporation of the worm gear and crank handle into the roller cotton gin, led to greatly expanded Indian cotton textile production.[51]

India's GDP per capita was lower than the Middle East from 1 CE (16% lower) to 1000 CE (about 40% lower), but by the late Delhi Sultanate era in 1500, India's GDP per capita approached that of the Middle East.[52]

GDP estimates

According to economic historian Angus Maddison in Contours of the world economy, 1–2030 AD: essays in macro-economic history, the Indian subcontinent was the world's most productive region, from 1 CE to 1600.[53]

| Year | GDP (PPP) (1990 dollars) |

GDP per capita (1990 dollars) |

Avg % GDP growth | % of world GDP (PPP) | Population | % of world population | Period | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33,750,000,000 | 450 | — | 32.0 | 70,000,000 | 30.3 | Classical era | |||

| 1000 | 33,750,000,000 | 450 | 0.0 | 28.0 | 72,500,000 | 27.15 | Early medieval era | |||

| 1500 | 60,500,000,000 | 550 | 0.117 | 24.35 | 79,000,000 | 18.0 | Late medieval era | |||

| Alternative estimates: | [54] | [55] | [56] | |||||||

| 1600 | 74,250,000,000 | 550 | 782 | 682 | 758 | 0.205 | 22.39 | 100,000,000 | 17.98 | Early modern era |

| 1700 | 90,750,000,000 | 550 | 719 | 622 | 697 | 0.201 | 24.43 | 165,000,000 | 27.36 | |

| 1820 | 111,417,000,000 | 533 | 580 | 520 | 562 | 0.171 | 16.04 | 209,000,000 | 20.06 | |

| 1870 | 134,882,000,000 | 533 | 526 | 526 | 510 | 0.975 | 12.14 | 253,000,000 | 19.83 | Colonial era |

| 1913 | 204,242,000,000 | 673 | 0.965 | 7.47 | 303,700,000 | 16.64 | ||||

| 1940 | 265,455,000,000 | 686 | 0.976 | 5.9 | 386,800,000 | 16.82 | ||||

| 1950 | 222,222,000,000 | 619 | -1.794 | 4.17 | 359,000,000 | 14.11 | Republic of India | |||

| 1990 | 1,098,100,000,000 | 1,309 | 4.075 | 4.05 | 839,000,000 | 15.92 | ||||

Medieval India

Economy of India under Mughal Empire, Maratha Empire and among others was prosperous into the early 18th century.[57] Parthasarathi estimated that 28,000 tonnes of bullion (mainly from the New World) flowed into the Indian subcontinent between 1600 and 1800, equating to 20% of the world's production in the period.[58]

An estimate of the annual income of Emperor Akbar the Great's treasury, in 1600, is £17.5 million (in contrast to the tax take of Great Britain two hundred years later, in 1800, totaled £16 million). The South Asia region, in 1600, was estimated to be the second largest in the world, behind China's.[59]

Historian Shireen Moosvi estimates that Mughal India had a per-capita income 1.24% higher in the late 16th century than British India had in the early 20th century, although the difference would be less if increasing purchasing power in terms of manufactured goods were taken into account. She also estimates that the secondary sector contributed a higher percentage to the Mughal economy (18.2%) than it did to the economy of early 20th-century British India (11.2%).[60]

By the late 17th century, the Mughal Empire was at its peak and had expanded to include almost 90 percent of the Indian subcontinent. It enforced a uniform customs and tax-administration system. In 1700, the exchequer of the Emperor Aurangzeb reported an annual revenue of more than £100 million, or $450 million, more than ten times that of his contemporary Louis XIV of France,[61] while controlling just 7 times the population.

By 1700, Mughal India had become the world's largest economy, ahead of Qing China and Western Europe, containing approximately 24.2% of the World's population, and producing about a quarter of world output.[62] Mughal India produced about 25% of global industrial output into the early 18th century.[7] India's GDP growth increased under the Mughal Empire, exceeding growth in the prior 1,500 years.[63] The Mughals were responsible for building an extensive road system,[57] creating a uniform currency, and the unification of the country.[64] The Mughals adopted and standardized the rupee currency introduced by Sur Emperor Sher Shah Suri.[65] The Mughals minted tens of millions of coins, with purity of at least 96%, without debasement until the 1720s.[66] The empire met global demand for Indian agricultural and industrial products.[67]

Cities and towns boomed under the Mughal Empire, which had a relatively high degree of urbanization (15% of its population lived in urban centres), more urban than Europe at the time and British India in the 19th century.[68] Multiple cities had a population between a quarter-million and half-million people,[68] while some including Agra (in Agra Subah) hosted up to 800,000 people[69] and Dhaka (in Bengal Subah) with over 1 million.[70] 64% of the workforce were in the primary sector (including agriculture), while 36% were in the secondary and tertiary sectors.[71] The workforce had a higher percentage in non-primary sectors than Europe at the time; in 1700, 65–90% of Europe's workforce were in agriculture, and in 1750, 65–75% were in agriculture.[72]

Agriculture

Indian agricultural production increased.[57] Food crops included wheat, rice, and barley, while non-food cash crops included cotton, indigo and opium. By the mid-17th century, Indian cultivators had begun to extensively grow two crops from the Americas, maize and tobacco.[57] Bengali peasants learned techniques of mulberry cultivation and sericulture, establishing Bengal Subah as a major silk-producing region.[73] Agriculture was advanced compared to Europe, exemplified by the earlier common use of the seed drill.[74] The Mughal administration emphasized agrarian reform, which began under the non-Mughal Emperor Sher Shah Suri. Akbar adopted this and added more reforms.[75] The Mughal government funded the building of irrigation systems, which produced much higher crop yields and harvests.[57]

One reform introduced by Akbar was a new land revenue system called zabt. He replaced the tribute system with a monetary tax system based on a uniform currency.[66] The revenue system was biased in favour of higher value cash crops such as cotton, indigo, sugar cane, tree-crops, and opium, providing state incentives to grow cash crops, adding to rising market demand.[76] Under the zabt system, the Mughals conducted extensive cadastral surveying to assess the cultivated area. The Mughal state encouraged greater land cultivation by offering tax-free periods to those who brought new land under cultivation.[77]

According to evidence cited by economic historians Immanuel Wallerstein, Irfan Habib, Percival Spear, and Ashok Desai, per-capita agricultural output and standards of consumption in 17th-century Mughal India was higher than in 17th-century Europe and early 20th-century British India.[78]

Manufacturing

Until the 18th century, Mughal India was the most important manufacturing center for international trade.[79] Key industries included textiles, shipbuilding and steel. Processed products included cotton textiles, yarns, thread, silk, jute products, metalware, and foods such as sugar, oils and butter.[57] This growth of manufacturing has been referred to as a form of proto-industrialization, similar to 18th-century Western Europe prior to the Industrial Revolution.[80]

Early modern Europe imported products from Mughal India, particularly cotton textiles, spices, peppers, indigo, silks and saltpeter (for use in munitions).[57] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Indian textiles and silks. From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, Mughal India accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia, and the Bengal Subah province alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.[9] In contrast, demand for European goods in Mughal India was light. Exports were limited to some woolens, ingots, glassware, mechanical clocks, weapons, particularly blades for Firangi swords, and a few luxury items.[81] The trade imbalance caused Europeans to export large quantities of gold and silver to Mughal India to pay for South Asian imports.[57][81] Indian goods, especially those from Bengal, were also exported in large quantities to other Asian markets, such as Indonesia and Japan.[82]

The largest manufacturing industry was cotton textile manufacturing, which included the production of piece goods, calicos and muslins, available unbleached in a variety of colours. The cotton textile industry was responsible for a large part of the empire's international trade.[57] The most important center of cotton production was the Bengal Subah province, particularly around Dhaka.[83] Bengal alone accounted for more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks imported by the Dutch.[9] Bengali silk and cotton textiles were exported in large quantities to Europe, Indonesia and Japan.[84]

Mughal India had a large shipbuilding industry, particularly in the Bengal Subah province. Economic historian Indrajit Ray estimates shipbuilding output of Bengal during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries at 223,250 tons annually, compared with 23,061 tons produced in nineteen colonies in North America from 1769 to 1771.[85]

Bengal Subah

Bengal Subah was the Mughal's wealthiest province, generating 50% of the empire's GDP and 12% of the world's GDP.[86] According to Ray, it was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding.[87] Bengal's capital city Dhaka was the empire's financial capital, with a population exceeding one million. It was an exporter of silk and cotton textiles, steel, saltpeter and agricultural and industrial products.[86]

Domestically, much of India depended on Bengali products such as rice, silks and cotton textiles.[9][84]

Post–Mughal Empire

In the early half of the 18th century, Mughal Empire fell into decline, with Delhi sacked in Nader Shah's invasion of the Mughal Empire, the treasury emptied, tens of thousands killed, and many thousands more carried off, with their livestock, as slaves, weakening the empire and leading to the emergence of post-Mughal states. The Mughals were replaced by the Marathas as the dominant military power in much of India, while the other smaller regional kingdoms who were mostly late Mughal tributaries, such as the Nawabs in the north and the Nizams in the south, declared autonomy. However, the efficient Mughal tax administration system was left largely intact, with Tapan Raychaudhuri estimating revenue assessment actually increased to 50 percent or more, in contrast to China's 5 to 6 percent, to cover the cost of the wars.[88] Similarly in the same period, Maddison gives the following estimates for the late Mughal economy's income distribution:

| Social group | % of population | % of total income | Income in terms of per-capita mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nobility, Zamindars | 1 | 15 | 15 |

| Merchants to Sweapers | 17 | 37 | 2.2 |

| Village Economy | 72 | 45 | 0.6 |

| Tribal Economy | 10 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 1 |

Among the post-Mughal states that emerged in the 18th century, the dominant economic powers were Bengal Subah (under the Nawabs of Bengal) and the South Indian Kingdom of Mysore (under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan). The former was devastated by the Maratha invasions of Bengal,[90][91] which experienced six invasions, over a decade, claimed to have killed hundreds of thousands, blocked trade with the Persian and Ottoman empires, and weakened the territory's economy to the point the Nawab of Bengal agreed to a peace treaty with the Marathas.[92] The agreement made Bengal Subah a tributary to the Marathas, agreeing to pay Rs. 1.2 million in tribute annually, as the Chauth of Bengal and Bihar. The Nawab of Bengal also paid Rs. 3.2 million to the Marathas, towards the arrears of chauth for the preceding years. The chauth was paid annually by the Nawab of Bengal, up to his defeat at the Battle of Plassey by the East India Company in 1757.

Sivramkrishna states that the economy of the Kingdom of Mysore then overtook that of Bengal, with real income five times higher than subsistence level,[58] i.e. five times higher than $400 (1990 international dollars),[4] or $2,000 per capita. In comparison, Maddison estimates the 1820 GDP per-capita (PPP 1990 $) of the Netherlands at $1,838, and $1,706 for Britain.[93]

Jeffrey G. Williamson argued that India went through a period of deindustrialization in the latter half of the 18th century as an indirect outcome of the collapse of the Mughal Empire, and that British rule later caused further deindustrialization.[7] According to Williamson, the Mughal Empire's decline reduced agricultural productivity, which drove up food prices, then nominal wages, and then textile prices, which cost India textile market share to Britain even before the latter developed factory technology,[94] though Indian textiles maintained a competitive advantage over British textiles until the 19th century.[95] Prasannan Parthasarathi countered that several post-Mughal states did not decline, notably Bengal and Mysore, which were comparable to Britain into the late 18th century.[8]

British rule

The British East India Company conquered Bengal Subah at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. After gaining the right to collect revenue in Bengal in 1765, the East India Company largely ceased importing gold and silver, which it had hitherto used to pay for goods shipped back to Britain.

| Years | Bullion (£) | Average per Annum |

|---|---|---|

| 1708/9-1733/4 | 12,189,147 | 420,315 |

| 1734/5-1759/60 | 15,239,115 | 586,119 |

| 1760/1-1765/6 | 842,381 | 140,396 |

| 1766/7-1771/2 | 968,289 | 161,381 |

| 1772/3-1775/6 | 72,911 | 18,227 |

| 1776/7-1784/5 | 156,106 | 17,345 |

| 1785/6-1792/3 | 4,476,207 | 559,525 |

| 1793/4-1809/10 | 8,988,165 | 528,715 |

In addition, as under Mughal rule, land revenue collected in the Bengal Presidency helped finance the Company's wars in other parts of India. Consequently, in the period 1760–1800, Bengal's money supply was greatly diminished. The closing of some local mints and close supervision of the rest, the fixing of exchange rates and the standardization of coinage added to the economic downturn.[97]

During the period 1780–1860 India changed from an exporter of processed goods paid for in bullion to an exporter of raw materials and a buyer of manufactured goods.[97] In the 1750s fine cotton and silk was exported from India to markets in Europe, Asia, and Africa, while by the second quarter of the 19th century, raw materials, which chiefly consisted of raw cotton, opium, and indigo, accounted for most of India's exports.[98] From the late 18th century the British cotton mill industry began to lobby their government to tax Indian imports and allow them access to markets in India.[98] Starting in the 1830s, British textiles began to appear in—and then inundate—Indian markets, with the value of the textile imports growing from £5.2 million in 1850 to £18.4 million in 1896.[99] The abolition of slavery encouraged Caribbean plantations to organize the import of South Asian labor.[100]

Relative decline in productivity

India accounted for 25% of the world's industrial output in 1750, declining to 2% of the world's industrial output in 1900.[7] Britain replaced India as the world's largest textile manufacturer in the 19th century.[95] In terms of urbanization, Mughal India had a higher percentage of its population (15%) living in urban centers in 1600 than British India did in the 19th century.[68]

Several economic historians claimed that in the 18th century real wages were falling in India, and were "far below European levels".[102] This has been disputed by others, who argued that real wage decline occurred in the early 19th century, or possibly beginning in the late 18th century, largely as a result of "globalization forces".[7]

Clingingsmith and Williamson[103] argue India deindustrialized, in the period between 1750 and 1860, due to two very different causes, before reindustrialization. Between 1750 and 1810, they suggest the loss of Mughal hegemony allowed new despotic rulers to revenue farm their conquered populations, seeing tax and rent demands increase to 50% of production, compared to the 5–6% extracted in China during the period, and levied largely to fund regional warfare. Combined with the use of labour and livestock for martial purposes, grain and textile prices were driven up, along with nominal wages, as the populus attempted to meet the demands, reducing the competitiveness of Indian handicrafts, and impacting the regional textile trade. Then from 1810 to 1860, the expansion of the British factory system drove down the relative price of textiles worldwide, through productivity advances, a trend that was magnified in India as the concurrent transport revolution dramatically reduced transportation costs, and in a sub-continent that had not seen metalled roads, the introduction of mechanical transport exposed once protected markets to global competition, hitting artisanal manufacture, but stabilizing the agricultural sector.

Angus Maddison states:[104]

... This was a shattering blow to manufacturers of fine muslins, jewellery, luxury clothing and footwear, decorative swords and weapons. My own guess would be that the home market for these goods was about 5 percent of Moghul national income and the export market for textiles probably another 1.5 percent.

Amiya Bagchi estimates:

| Occupation | 1809–1813 | 1901 |

|---|---|---|

| Spinners | 10.3 | – |

| Spinners / Weavers | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| Other Industrial | 9.0 | 7.2 |

| TOTAL | 21.6 | 8.5 |

British East India Company rule (1764–1857)

During this period, the East India Company began tax administration reforms in a fast expanding empire spread over 250 million acres (1,000,000 km2), or 35 percent of Indian domain. Indirect rule was established on protectorates and buffer states.

Ray (2009) raises three basic questions about the 19th-century cotton textile industry in Bengal: when did the industry begin to decay, what was the extent of its decay during the early 19th century, and what were the factors that led to this? Since no data exist on production, Ray uses the industry's market performance and its consumption of raw materials. Ray challenges the prevailing belief that the industry's permanent decline started in the late 18th century or the early 19th century. The decline actually started in the mid-1820s. The pace of its decline was, however, slow though steady at the beginning, but reached a crisis by 1860, when 563,000 workers lost their jobs. Ray estimates that the industry shrank by about 28% by 1850. However, it survived in the high-end and low-end domestic markets. Ray agrees that British discriminatory policies undoubtedly depressed the industry's exports, but suggests its decay is better explained by technological innovations in Britain.[106]

Other historians point to colonization as a major factor in both India's deindustrialization and Britain's Industrial Revolution.[107][108][109][110] The capital amassed from Bengal following its 1757 conquest supported investment in British industries such as textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution as well as increasing British wealth, while contributing to deindustrialization in Bengal.[107][108][109] Colonization forced the large Indian market to open to British goods, which could be sold in India without tariffs or duties, compared to heavily taxed local Indian producers. In Britain protectionist policies such as high tariffs restricted Indian textile sales. By contrast, raw cotton was imported without tariffs to British factories which manufactured textiles and sold them back to India. British economic policies gave them a monopoly over India's large market and cotton resources.[111][95][112] India served as both a significant supplier of raw goods to British manufacturers and a large captive market for British manufactured goods.[113]

Indian textiles had maintained a competitive advantage over British textiles up until the 19th century, when Britain eventually overtook India as the world's largest cotton textile manufacturer.[95] In 1811, Bengal was still a major exporter of cotton cloth to the Americas and the Indian Ocean. However, Bengali exports declined over the course of the early 19th century, as British imports to Bengal increased, from 25% in 1811 to 93% in 1840.[114] By 1820, India had fallen from the top rank to become the second-largest economy in the world, behind China.[59]

Absence of industrialisation

Historians have questioned why India failed to industrialise in the 19th century. As the global cotton industry underwent a technological revolution in the 18th century, while Indian industry stagnated after adopting the Flying shuttle, and industrialisation began only in the late 19th century. Several historians have suggested that this was because India was still a largely agricultural nation with low Commodity money wage levels, arguing that nominal wages were high in Britain so cotton producers had the incentive to invent and purchase expensive new labour-saving technologies, and that wages levels were low in India so producers preferred to increase output by hiring more workers rather than investing in technology.[115]

Economic historians such as Prasannan Parthasarathi have criticized this argument, pointing to earnings data that show Real wages in 18th-century Bengal and Mysore were higher than in Britain.[8][7] Instead, Parthasarathi argues that Indian textile prices were lower because of India's lower food prices, which was the result of higher agricultural productivity. Compared to Britain, the silver coin prices of grain were about one-half in Mysore and one-third in Bengal, resulting in lower silver coin prices for Indian textiles, giving them a price advantage in global markets.[8] According to evidence cited by Immanuel Wallerstein, Irfan Habib, Percival Spear and Ashok Desai, per-capita agricultural output and standards of consumption in 17th-century Mughal India was higher than in 17th-century Europe and early 20th-century British India.[78]

Stephen Broadberry and Bishnupriya Gupta gave the following comparative estimates for Indian and UK populations and GDP per capita during 1600–1871 in terms of 1990 international dollars.[54][116][117]

| Year | India ($) | UK ($) | Ratio (%) | India population (m) | UK population (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1600 | 782 | 1,104 | 72 | 142 | 5 |

| 1650 | 736 | 904 | 83 | 142 | 5.8 |

| 1700 | 719 | 1,477 | 49.3 | 164 | 8.8 |

| 1751 | 661 | 1,678 | 39.9 | 190 | 9.2 |

| 1801 | 639 | 2,142 | 32.6 | 207 | 16.3 |

| 1851 | 586 | 2,721 | 21.9 | 232 | 27.5 |

| 1871 | 526 | 3,629 | 14.5 | 256 | 31.6 |

However, Parthasarathi criticised the per-capita GDP estimates from Broadberry and Gupta.[58][7] Workers in the textile industry, for example, earned more in Bengal and Mysore than they did in Britain, while agricultural labour in Britain had to work longer hours to earn the same amount as in Mysore.[8] Others such as Andre Gunder Frank, Robert A. Denemark, Kenneth Pomeranz and Amiya Kumar Bagchi also criticised estimates that showed low per-capita income and GDP growth rates in Asia (especially China and India) prior to the 19th century, pointing to later research that found significantly higher per-capita income and growth rates in China and India during that period.[118]

Economic historian Sashi Sivramkrishna estimates Mysore's average per-capita income in the late 18th century to be five times higher than subsistence,[58] i.e. five times higher than $400 (1990 international dollars),[4] or $2,000 per capita. In comparison, the highest national per-capita incomes in 1820 were $1,838 for the Netherlands and $1,706 for Britain.[93] According to economic historian Paul Bairoch, India as well as China had a higher GDP per capita than Europe in 1750.[119][120] For 1750, Bairoch estimated the GNP per capita for the Western world to be $182 in 1960 US dollars ($804 in 1990 dollars) and for the non-Western world to be $188 in 1960 dollars ($830 in 1990 dollars), exceeded by both China and India.[121] Other estimates he gives include $150–190 for England in 1700 and $160–210 for India in 1800.[122] Bairoch estimated that it was only after 1800 that Western European per-capita income pulled ahead.[123]

Indian Ordnance Factories

In 1787, a Gunpowder Factory was established at Ishapore; it began production in 1791, it is now the Rifle Factory Ishapore, beginning in 1904. In 1801, Gun & Shell Factory, Calcutta was established and the production began on 18 March 1802. There were eighteen ordnance factories before India became independent in 1947.[124]

British Raj (1858–1947)

The formal dissolution of the Mughal Dynasty heralded a change in British treatment of Indian subjects. During the British Raj, massive railway projects were begun in earnest and government jobs and guaranteed pensions attracted a large number of upper caste Hindus into the civil service for the first time. British cotton exports absorbed 55 percent of the Indian market by 1875.[125] In the 1850s the first cotton mills opened in Bombay, posing a challenge to the cottage-based home production system based on family labour.[126]

Fall of the rupee

| Period | Price of silver (in pence per troy ounce) | Rupee exchange rate (in pence) |

|---|---|---|

| 1871–1872 | 60½ | 23 ⅛ |

| 1875–1876 | 56¾ | 21⅝ |

| 1879–1880 | 51¼ | 20 |

| 1883–1884 | 50½ | 19½ |

| 1887–1888 | 44⅝ | 18⅞ |

| 1890–1951 | 47 11/16 | 18⅛ |

| 1891–1892 | 45 | 16¾ |

| 1892–1893 | 39 | 15 |

| Source: B.E. Dadachanji. History of Indian Currency and Exchange, 3rd enlarged ed.

(Bombay: D.B. Taraporevala Sons & Co, 1934), p. 15 | ||

After its victory in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), Germany extracted a huge indemnity from France of £200,000,000, and then moved to join Britain on a gold monetary standard. France, the US, and other industrialising countries followed Germany in adopting gold in the 1870s. Countries such as Japan that did not have the necessary access to gold or those, such as India, that were subject to imperial policies remained mostly on a silver standard. Silver-based and gold-based economies then diverged dramatically. The worst affected were silver economies that traded mainly with gold economies. Silver reserves increased in size, causing gold to rise in relative value. The impact on silver-based India was profound, given that most of its trade was with Britain and other gold-based countries. As the price of silver fell, so too did the exchange value of the rupee, when measured against sterling.

Agriculture and industry

The Indian economy grew at about 1% per year from 1890 to 1910, matching population growth.[127] The result was no change in income levels. Agriculture was still dominant, with most peasants at the subsistence level.

Entrepreneur Jamsetji Tata (1839–1904) began his industrial career in 1877 with the Central India Spinning, Weaving, and Manufacturing Company in Bombay. While other Indian mills produced cheap coarse yarn (and later cloth) using local short-staple cotton and simple machinery imported from Britain, Tata did much better by importing expensive longer-stapled cotton from Egypt and buying more complex ring-spindle machinery from the United States to spin finer yarn that could compete with imports from Britain.[128]

In the 1890s, Tata launched plans to expand into the heavy industry using Indian funding. The Raj did not provide capital, but aware of Britain's declining position against the U.S. and Germany in the steel industry, it wanted steel mills in India so it promised to purchase any surplus steel Tata could not otherwise sell.[129]

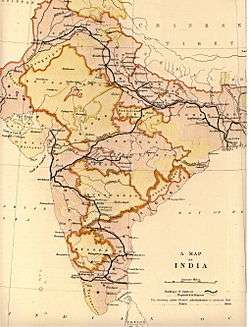

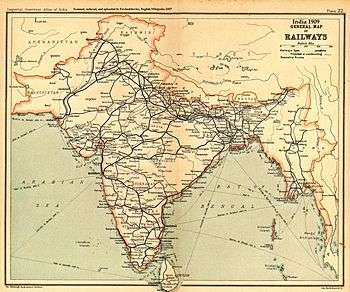

Railways

British investors built a modern railway system in the late 19th century—it became the then fourth-largest in the world and was renowned for the quality of construction and service.[130] The government was supportive, realising its value for military use and for economic growth. The railways at first were privately owned and operated, and run by British administrators, engineers and skilled craftsmen. At first, only the unskilled workers were Indians.[131]

A plan for a rail system was first advanced in 1832. The first train ran from Red Hills to Chintadripet bridge in Madras, inaugurated in 1837. It was called Red Hill Railway.[132] It was used for freight transport. A few more short lines were built in the 1830s and 1840s. They did not interconnect and were used for freight forwarding. The East India Company (and later the colonial government) encouraged new railway companies backed by private investors under a scheme that would provide land and guarantee an annual return of up to five percent during the initial years of operation. The companies were to build and operate the lines under a 99-year lease, with the government retaining the option to buy them earlier.[132] In 1854 Governor-General Lord Dalhousie formulated a plan to construct a network of trunk lines connecting the principal regions. A series of new rail companies were established, leading to rapid expansion.[133]

In 1853, the first passenger train service was inaugurated between Bori Bunder in Bombay and Thane, covering a distance of 34 km (21 mi).[134] The route mileage of this network increased from 1,349 km (838 mi) in 1860 to 25,495 km (15,842 mi) in 1880 – mostly radiating inland from the port cities of Bombay, Madras and Calcutta.[135] Most of the railway construction was done by Indian companies supervised by British engineers. The system was sturdily built. Several large princely states built their own rail systems and the network spread across India.[132] By 1900 India had a full range of rail services with diverse ownership and management, operating on broad, metre and narrow gauge networks.[136]

Headrick argues that both the Raj lines and the private companies hired only European supervisors, civil engineers and even operating personnel, such as locomotive engineers. The government's Stores Policy required that bids on railway contracts be submitted to the India Office in London, shutting out most Indian firms. The railway companies purchased most of their hardware and parts in Britain. Railway maintenance workshops existed in India, but were rarely allowed to manufacture or repair locomotives. TISCO first won orders for rails only in the 1920s.[137] Christensen (1996) looked at colonial purpose, local needs, capital, service and private-versus-public interests. He concluded that making the railways dependent on the state hindered success, because railway expenses had to go through the same bureaucratic budgeting process as did all other state expenses. Railway costs could therefore not respond to needs of the railways or their passengers.[138]

In 1951, forty-two separate railway systems, including thirty-two lines owned by the former Indian princely states, were amalgamated to form a single unit named the Indian Railways. The existing rail systems were abandoned in favor of zones in 1951 and a total of six zones came into being in 1952.[136]

Economic impact of imperialism

.png)

Debate continues about the economic impact of British imperialism on India. The issue was first raised by Edmund Burke who in the 1780s vehemently attacked the East India Company, claiming that Warren Hastings and other top officials had ruined the Indian economy and society, and elaborated on in the 19th century by Romesh Chunder Dutt. Indian historian Rajat Kanta Ray (1998) continued this line of reasoning, saying that British rule in the 18th century took the form of plunder and was a catastrophe for the traditional economy. According to the economic drain theory, supported by Ray, the British depleted food, and money stocks and imposed high taxes that helped cause the terrible famine of 1770, which killed a third of the people of Bengal.[139] Ray also argued British India failed to offer the necessary encouragement, technology transfers, and protectionist frameworks, to permit British India to replicate Britain’s own industrialisation, before its independence.[140]

British historian P. J. Marshall reinterpreted the view that the prosperity of the Mughal era gave way to poverty and anarchy, arguing that the British takeover was not a sharp break with the past. British control was delegated largely through regional rulers and was sustained by a generally prosperous economy through the 18th century, except for the frequent, deadly famines. Marshall notes the British raised revenue through local tax administrators and kept the old Mughal tax rates. Instead of the Indian nationalist account of the British as alien aggressors, seizing power by brute force and impoverishing the region, Marshall presents a British nationalist interpretation in which the British were not in full control, but instead were controllers in what was primarily an Indian-run society and in which their ability to keep power depended upon cooperation with Indian elites. Marshall admitted that much of his interpretation is rejected by many historians.[141]

Colonial Boom (1910–30)

British colonial rule created an institutional environment that stabilized Indian society, though they stifled trade with the rest of the world. They created a well-developed system of railways, telegraphs and a modern legal system. Extensive irrigation systems were built, providing an impetus for growing cash crops for export and for raw materials for Indian industry, especially jute, cotton, sugarcane, coffee, and tea.[142]

The Tata Iron and Steel Company (TISCO), headed by Dorabji Tata, opened its plant at Jamshedpur in Bihar in 1908. It became the leading iron and steel producer in India, with 120,000 employees in 1945.[143] TISCO became an India's symbol of technical skill, managerial competence, entrepreneurial flair, and high pay for industrial workers.[144]

During the First World War, the railways were used to transport troops and grains to Bombay and Karachi en route to Britain, Mesopotamia and East Africa. With shipments of equipment and parts from Britain curtailed, maintenance became much more difficult; critical workers entered the army; workshops were converted to make artillery; locomotives and cars were shipped to the Middle East. The railways could barely keep up with the sudden increase in demand.[145] By the end of the war, the railways had deteriorated badly.[146][136] In the Second World War the railways' rolling stock was diverted to the Middle East, and the railway workshops were again converted into munitions workshops.[147]

Non-royal private wealth was encouraged by colonial administrations during these times. Houses of Birla and Sahu Jain began to challenge the Houses of Martin Burn, Bird Heilgers and Andrew Yule. About one-ninth of the national population were urban by 1925.

Economic Bust (1930–50)

The 20-year economic boom cycle ended with the Great Depression of 1929 that had a direct impact on India, with relatively little impact on the modern secondary sector. The colonial administration did little to alleviate debt stress.[148] The worst consequences involved deflation, which increased the burden of the debt on villagers.[149] Total economic output did not decline between 1929 and 1934. The worst-hit sector was jute, based in Bengal, which was an important element in overseas trade; it had prospered in the 1920s but prices dropped in the 1930s.[150] Employment also decline, while agriculture and small-scale industry exhibited gains.[151] The most successful new industry was sugar, which had meteoric growth in the 1930s.[152][153]

Gold-Silver ratio peaked at 100-1 by 1940. The Bank of England records the Indian central bank held a positive balance of £1,160 million on 14 July 1947, and that British India maintained a trade surplus, with the United Kingdom, for the duration of the British Raj eg.[154]

| Period | Balance of trade and net invisibles | War expenditure | Other sources | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| September 1939 – March 1940 | 65 | 2 | 13 | 80 |

| 1940–41 | 57 | 30 | 6 | 93 |

| 1941–42 | 73 | 146 | 6 | 225 |

| 1942–43 | 92 | 244 | 7 | 343 |

| 1943–44 | 105 | 289 | 3 | 397 |

| 1944–45 | 92 | 308 | 2 | 402 |

| 1945–46 | 70 | 282 | 3 | 355 |

| Total | 554 | 1,301 | 40 | 1,895 |

Source: Indian sterling balances, p. 2, 15 Jan.1.1947, Bank of England (BoE), OV56/55.

The newly independent but weak Union government's treasury reported annual revenue of £334 million in 1950. In contrast, Nizam Asaf Jah VII of Hyderabad State was widely reported to have a fortune of almost £668 million then.[155] About one-sixth of the national population were urban by 1950.[156] A US Dollar was exchanged at 4.79 rupees.

British Raj's impact on productivity

Modern economic historians have blamed the colonial rule for the dismal state of India's economy, with investment in Indian industries limited since it was a colony.[157][158] Under British rule, India's native manufacturing industries shrank.[111][95][112] During the British East India Company's rule in India, production of food crops declined, mass impoverishment and destitution of farmers and numerous famines.[159] The economic policies of the British Raj caused a severe decline in the handicrafts and handloom sectors, with reduced demand and dipping employment;[160] the yarn output of the handloom industry, for example, declined from 419 million pounds in 1850 to 240 million pounds in 1900.[7] The result was a significant transfer of capital from India to England, which led to a massive drain of revenue rather than any systematic effort at modernisation of the Indian economy.[161]

There is no doubt that our grievances against the British Empire had a sound basis. As the painstaking statistical work of the Cambridge historian Angus Maddison has shown, India's share of world income collapsed from 22.6% in 1700, almost equal to Europe's share of 23.3% at that time, to as low as 3.8% in 1952. Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, "the brightest jewel in the British Crown" was the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita income.

Republic of India

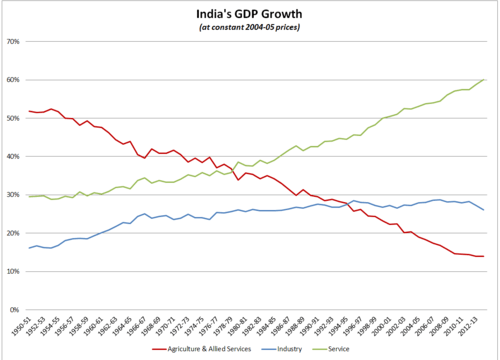

Hindu rate of growth

.png)

The phrase "Hindu rate of growth" is used to refer to the low annual growth rate of the economy of India before 1991. It remained around 3.5% from the 1950s to 1980s, while per capita income growth averaged 1.3% a year.[163] During the same period, South Korea grew by 10% and Taiwan by 12%.[164]

Socialist Boom (1950–1970)

Before independence a large share of tax revenue was generated by the land tax. Thereafter land taxes steadily declined as a share of revenues.[165]

The economic problems inherited at independence were exacerbated by the costs associated with the partition, which had resulted in about 2 to 4 million refugees fleeing past each other across the new borders between India and Pakistan. Refugee settlement was a considerable economic strain. Partition divided India into complementary economic zones. Under the British, jute and cotton were grown in the eastern part of Bengal (East Pakistan, after 1971, Bangladesh), but processing took place mostly in the western part of Bengal, which became the Indian state of West Bengal. As a result, after independence India had to convert land previously used for food production to cultivate cotton and jute.[166]

Growth continued in the 1950s, the rate of growth was less positive than India's politicians expected.[167]

Toward the end of Nehru's term as prime minister, India experienced serious food shortages.

Beginning in 1950, India faced trade deficits that increased in the 1960s. The Government of India had a major budget deficit and therefore could not borrow money internationally or privately. As a result, the government issued bonds to the Reserve Bank of India, which increased the money supply, leading to inflation. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 led the US and other countries friendly towards Pakistan to withdraw foreign aid to India, which necessitated devaluation. India was told it had to liberalise trade before aid would resume. The response was the politically unpopular step of devaluation accompanied by liberalisation. Defence spending in 1965/1966 was 24.06% of expenditure, the highest in the period from 1965 to 1989. Exacerbated by the drought of 1965/1966, the devaluation was severe. GDP per capita grew 33% in the 1960s, reaching a peak growth of 142% in the 1970s, before decelerating to 41% in the 1980s and 20% in the 1990s.[168]

From FY 1951 to FY 1979, the economy grew at an average rate of about 3.1 percent a year, or at an annual rate of 1.0 percent per capita.[169] During this period, industry grew at an average rate of 4.5 percent a year, compared with 3.0 percent for agriculture.[170][171]

| Year | Gross domestic product

(000,000 rupees) |

₹ per USD | Per Capita Income (as % of US) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 100,850 | 4.79 | 3.12 |

| 1955 | 110,300 | 4.79 | 2.33 |

| 1960 | 174,070 | 4.77 | 2.88 |

| 1965 | 280,160 | 4.78 | 3.26 |

Economic Bust (1970–90)

The 20-year economic boom cycle ended in 1971 with the Nixon shock. In 1975 India's GDP (in 1990 US dollars) was $545 billion, $1,561 billion in the USSR, $1,266 billion in Japan, and $3,517 billion in the US.[173]

Prime minister Indira Gandhi proclaimed a national emergency and suspended the Constitution in 1975. About one-fifth of the national population were urban by 1975.[174]

Steel

Prime Minister Nehru was a believer in socialism and decided that India needed maximum steel production. He, therefore, formed a government-owned company, Hindustan Steel Limited (HSL) and set up three steel plants in the 1950s.[175]

Capitalist Boom (1990–2010)

Economic liberalisation in India in the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century led to large economic changes.

| Year | Gross Domestic Product | Exports | Imports | ₹ per USD | Inflation Index (2000=100) | Per Capita Income (as % of US) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 5,542,706 | 406,350 | 486,980 | 17.50 | 42 | 1.56 |

| 1995 | 11,571,882 | 1,307,330 | 1,449,530 | 32.42 | 69 | 1.32 |

| 2000 | 21,774,130 | 2,781,260 | 2,975,230 | 44.94 | 100 | 1.26 |

| 2005 | 36,933,690 | 7,120,870 | 8,134,660 | 44.09 | 121 | 1.64 |

About one-fourth of the national population was urban by 2000.[181]

The Indian steel industry began expanding into Europe in the 21st century. In January 2007 India's Tata bought European steel maker Corus Group for $11.3 billion. In 2006 Mittal Steel (based in London but with Indian management) acquired Arcelor for $34.3 billion to become the world's biggest steel maker, ArcelorMittal, with 10% of world output.[182]

The GDP of India in 2007 was estimated at about 8 percent that of the US. The government started the Golden Quadrilateral road network connecting Delhi, Chennai, Mumbai and Kolkata with various Indian regions. The project, completed in January 2012, was the most ambitious infrastructure project of independent India.[183][184]

The top 3% of the population still earn 50% of GDP.

Economic Bust (2010–present)

The 20-year economic boom cycle ended in 2012. Productivity stagnated and economic activity remains limited by poor infrastructure such as dilapidated roads, electricity shortages and a cumbersome justice system.[185]

| Year | GDP | Exports | Imports | ₹ per USD | Inflation Index

(2000=100) |

Per Capita Income (as % of US) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 77,953,140 | 17,101,930 | 20,501,820 | 45.83 | 185 | 2.01 |

| 2012 | 100,020,620 | 23,877,410 | 31,601,590 | 54.93 | 219 | 2.90 |

For purchasing power parity comparisons, the US dollar is converted at 9.46 rupees. Despite continuous real GDP growth of at least 5% since 2009, the Indian economy is mired in bureaucratic hurdles. This was confirmed by a World Bank report published in late 2006 ranking Pakistan (at 74th) well ahead of India (at 134th) based on ease of doing business.[187]

GDP post-Independence

| Year | India's GDP at Current Prices (in crores INR) | India's GDP at Constant 2004–2005 Prices (in crores INR) | Real Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950–51 | ₹10,036 | ₹279,618 | |

| 1951–52 | ₹10,596 | ₹286,147 | 2.33% |

| 1952–53 | ₹10,449 | ₹294,267 | 2.84% |

| 1953–54 | ₹11,378 | ₹312,177 | 6.09% |

| 1954–55 | ₹10,689 | ₹325,431 | 4.25% |

| 1955–56 | ₹10,861 | ₹333,766 | 2.56% |

| 1956–57 | ₹12,965 | ₹352,766 | 5.69% |

| 1957–58 | ₹13,255 | ₹348,500 | −1.21% |

| 1958–59 | ₹14,827 | ₹374,948 | 7.59% |

| 1959–60 | ₹15,574 | ₹383,153 | 2.19% |

| 1960–61 | ₹17,049 | ₹410,279 | 7.08% |

| 1961–62 | ₹17,992 | ₹423,011 | 3.10% |

| 1962–63 | ₹19,238 | ₹431,960 | 2.12% |

| 1963–64 | ₹21,986 | ₹453,829 | 5.06% |

| 1964–65 | ₹25,686 | ₹488,247 | 7.58% |

| 1965–66 | ₹26,895 | ₹470,402 | −3.65% |

| 1966–67 | ₹30,613 | ₹475,190 | 1.02% |

| 1967–68 | ₹35,976 | ₹513,860 | 8.14% |

| 1968–69 | ₹37,938 | ₹527,270 | 2.61% |

| 1969–70 | ₹41,722 | ₹561,630 | 6.52% |

| 1970–71 | ₹44,382 | ₹589,787 | 5.01% |

| 1971–72 | ₹47,221 | ₹595,741 | 1.01% |

| 1972–73 | ₹51,943 | ₹593,843 | −0.32% |

| 1973–74 | ₹63,658 | ₹620,872 | 4.55% |

| 1974–75 | ₹74,930 | ₹628,079 | 1.16% |

| 1975–76 | ₹79,582 | ₹684,634 | 6.00% |

| 1976–77 | ₹85,545 | ₹693,191 | 1.25% |

| 1977–78 | ₹97,633 | ₹744,972 | 7.47% |

| 1978–79 | ₹104,930 | ₹785,965 | 5.50% |

| 1979–80 | ₹114,500 | ₹745,083 | −5.20% |

| 1980–81 | ₹136,838 | ₹798,506 | 7.17% |

| 1981–82 | ₹160,214 | ₹843,426 | 5.63% |

| 1982–83 | ₹178,985 | ₹868,092 | 2.92% |

| 1983–84 | ₹209,356 | ₹936,270 | 7.85% |

| 1984–85 | ₹230,526 | ₹973,357 | 3.96% |

| 1985–86 | ₹262,717 | ₹1,013,866 | 4.16% |

| 1986–87 | ₹292,924 | ₹1,057,612 | 4.31% |

| 1987–88 | ₹332,068 | ₹1,094,993 | 3.53% |

| 1988–89 | ₹396,295 | ₹1,206,243 | 8.16% |

| 1989–90 | ₹456,540 | ₹1,280,228 | 6.13% |

| 1990–91 | ₹531,814 | ₹1,347,889 | 5.29% |

| 1991–92 | ₹613,528 | ₹1,367,171 | 1.43% |

| 1992–93 | ₹703,723 | ₹1,440,504 | 5.36% |

| 1993–94 | ₹805,486 | ₹1,522,344 | 5.68% |

| 1994–95 | ₹955,386 | ₹1,619,694 | 6.39% |

| 1995–96 | ₹1,118,586 | ₹1,737,741 | 7.29% |

| 1996–97 | ₹1,301,788 | ₹1,876,319 | 7.97% |

| 1997–98 | ₹1,447,613 | ₹1,957,032 | 4.30% |

| 1998–99 | ₹1,668,739 | ₹2,087,828 | 6.68% |

| 1999–00 | ₹1,858,205 | ₹2,254,942 | 8.00% |

| 2000–01 | ₹2,000,743 | ₹2,348,481 | 4.15% |

| 2001–02 | ₹2,175,260 | ₹2,474,962 | 5.39% |

| 2002–03 | ₹2,343,864 | ₹2,570,935 | 3.88% |

| 2003–04 | ₹2,625,819 | ₹2,775,749 | 7.97% |

| 2004–05 | ₹2,971,464 | ₹2,971,464 | 7.05% |

| 2005–06 | ₹3,390,503 | ₹3,253,073 | 9.48% |

| 2006–07 | ₹3,953,276 | ₹3,564,364 | 7.57% |

| 2007–08 | ₹4,582,086 | ₹3,896,636 | 5.32% |

| 2008–09 | ₹5,303,567 | ₹4,158,676 | 3.08% |

| 2009–10 | ₹6,108,903 | ₹4,516,071 | 4.59% |

| 2010–11 | ₹7,248,860 | ₹4,918,533 | 6.91% |

| 2011–12 | ₹8,391,691 | ₹5,247,530 | 6.69% |

| 2012–13 | ₹9,388,876 | ₹5,482,111 | 4.47% |

| 2013–14 | ₹10,472,807 | ₹5,741,791 | 4.74% |

See also

- Timeline of the economy of the Indian subcontinent

- Demographics of India

- History of agriculture in India

- History of banking in India

- History of India

- List of regions by past GDP (PPP)

- List of regions by past GDP (PPP) per capita

- List of countries by past and projected GDP (nominal)

References

- Mukherjee, Money and Social Changes in India 2012, p. 412.

- Paul Bairoch (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-226-03463-8.

- "Power of Data Visualisation".

- Angus Maddison (2007). The World Economy Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective Volume 2: Historical Statistics. Academic Foundation. p. 260. ISBN 9788171886135.

- "The World Economy (GDP) : Historical Statistics by Professor Angus Maddison" (PDF). World Economy. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Maddison, Angus (2006). The World Economy – Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective and Volume 2: Historical Statistics. OECD Publishing by Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. p. 656. ISBN 9789264022621.

- Jeffrey G. Williamson, David Clingingsmith (August 2005). "India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 38, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference US, 2006, pp. 237–40, World History in Context, accessed 3 August 2017

- József Böröcz (10 September 2009). The European Union and Global Social Change. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 9781135255800. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- Ishat Pandey (2017). The Sketch of The Mughal Empire. Lulu Publishers. ISBN 9780359221202.

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam (1998). Money and the Market in India, 1100–1700. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780521257589.

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 207, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 45, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- S. A. A. Rizvi, p. 263 of A Cultural History of India (1975), edited by A. L. Basham

- Maddison 2003, p. 261.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 250. ISBN 9781107507180.

- "Economic survey of India 2007: Policy Brief" (PDF). OECD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2011.

- "Industry passing through phase of transition". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014.

- Pandit, Ranjit V. (2005). "Why believe in India". McKinsey.

- Marshall, John (1996). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927. p. 481. ISBN 9788120611795.

- Chopra, Pran Nath (2003). A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set). Sterling. p. 73. ISBN 9788120725034.

- Ārya, Samarendra Nārāyaṇa (2004). History of Pilgrimage in Ancient India: Ad 300–1200. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Limited. pp. 3, 74.

- Mahaprajna, Acharya (2001). Anekant: Views And Issues (First ed.). Ladnun, India: Jain Vishwa Bharati University, Ladnun, India. p. 46.

- Sarien, R. G. (1973). Managerial styles in India: proceedings of a seminar. p. 19.

- M. K. Kuriakose, History of Christianity in India: Source Materials, (Bangalore: United Theological College, 1982), pp. 10–12. Kuriakose gives a translation of the related but later copper plate grant to Iravi Kortan on pp. 14–15. For earlier translations, see S. G. Pothan, The Syrian Christians of Kerala, (Bombay: Asia Publishing House, 1963), pp. 102–105.

- Khanna 2005.

- Jataka IV.

- "The Chera Coins". Tamilartsacademy.com. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- Ghosh, Amalananda (1990). An Encyclopaedia of Indian Archaeology. BRILL. p. 12. ISBN 9789004092648.

- Ratan Lal Basu & Rajkumar Sen, Ancient Indian Economic Thought, Relevance for Today ISBN 81-316-0125-0, Rawat Publications, New Delhi, 2008.

- Raychaudhuri & Habib 2004, pp. 17–18

- Raychaudhuri & Habib 2004, pp. 40–41

- Hanway, Jonas (1753), An Historical Account of the British Trade Over the Caspian Sea, Sold by Mr. Dodsley,

... The Persians have very little maritime strength ... their ship carpenters on the Caspian were mostly Indians ... there is a little temple, in which the Indians now worship

- Stephen Frederic Dale (2002), Indian Merchants and Eurasian Trade, 1600–1750, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-52597-8,

... The Russian merchant, F.A. Kotov ... saw in Isfahan in 1623, both Hindus and Muslims, as Multanis.

- Scott Cameron Levi (2002), The Indian diaspora in Central Asia and its trade, 1550–1900, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-12320-5,

... George Forster ... On the 31st of March, I visited the Atashghah, or place of fire; and on making myself known to the Hindoo mendicants, who resided there, I was received among these sons of Brihma as a brother

- Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson (1911), From Constantinople to the home of Omar Khayyam: travels in Transcaucasia and northern Persia for historic and literary research, The Macmillan company

- George Forster (1798), A journey from Bengal to England: through the northern part of India, Kashmire, Afghanistan, and Persia, and into Russia, by the Caspian-Sea, R. Faulder,

... A society of Moultan Hindoos, which has long been established in Baku, contributes largely to the circulation of its commerce; and with the Armenians they may be accounted the principal merchants of Shirwan ...

- James Justinian Morier (1818), A Second Journey through Persia, Armenia, and Asia Minor, to Constantinople, between the Years 1810 and 1816, A. Strahan

- United States Bureau of Foreign Commerce (1887), Reports from the consuls of the United States, 1887, United States Government,

... Six or 7 miles southeast is Surakhani, the location of a very ancient monastery of the fire-worshippers of India ...

- Raychaudhuri & Habib 2004, pp. 10–13

- Datt & Sundharam 2009, p. 14

- Asher, C. B.; Talbot, C (1 January 2008), India Before Europe (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 50–52, ISBN 978-0-521-51750-8

- Pacey, Arnold (1991) [1990]. Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (First MIT Press paperback ed.). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press. pp. 26–29.

- Habib, Irfan (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500. Pearson Education India. p. 96. ISBN 9788131727911.

- Pacey, Arnold (1991) [1990]. Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History (First MIT Press paperback ed.). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press. pp. 23–24.

- Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500, page 53, Pearson Education

- Lakwete, Angela (2003). Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 9780801873942.

- Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500, pages 53–54, Pearson Education

- Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500, page 54, Pearson Education

- Angus Maddison (2010). "Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1–2008 AD". University of Groningen.

- Maddison, Angus (6 December 2007). Contours of the world economy, 1–2030 AD: essays in macro-economic history. Oxford University Press. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-19-922720-4.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2010). "Indian GDP before 1870: Some preliminary estimates and a comparison with Britain" (PDF). Warwick University. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2015). "India and the great divergence: an Anglo-Indian comparison of GDP per capita, 1600–1871". Explorations in Economic History. 55: 58–75. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2014.04.003. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- Bolt, Jutta; Inklaar, Robert (2018). "Maddison Project Database 2018". University of Groningen. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- Schmidt, Karl J. (20 May 2015). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47681-8.

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 45, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy, Volumes 1–2. OECD Publishing. p. 638. doi:10.1787/456125276116. ISBN 978-92-64-02261-4. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- Moosvi, Shireen (2015) [First published 1989]. The Economy of the Mughal Empire c. 1595: A Statistical Study (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 432–433. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199450541.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-908549-1.

- Harrison, Lawrence; Berger, Peter L. (2006). Developing cultures: case studies. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 9780415952798.

- Maddison 2003, p. 259.

- Maddison 2003, p. 257.

- Richards 1996, p. 185–204.

- Picture of original Mughal rupiya introduced by Sher Shah Suri Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Richards 2003, p. 27.

- Richards 1996, p. 73–74.

- Eraly, Abraham (2007). The Mughal World: Life in India's Last Golden Age. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-310262-5.

- Habib, Kumar & Raychaudhur 1987, p. 171.

- Social Science Review. Registrar, Dhaka University. 1997.

- Yazdani, Kaveh (10 January 2017). India, Modernity and the Great Divergence: Mysore and Gujarat (17th to 19th C.). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-33079-5.

- Cipolla, Carlo M. (2004). Before the Industrial Revolution: European Society and Economy 1000–1700. Routledge.

- Richards 1996, p. 190.

- Habib, Kumar & Raychaudhuri 1987, p. 230.

- Ignacio Pichardo Pagaza; Demetrios Argyriades (2009). Winning the Needed Change: Saving Our Planet Earth : a Global Public Service. IOS Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-58603-958-5.

- Richards 1996, p. 174.

- Richards 2003, p. 28.

- Suneja, Vivek (2000). Understanding Business: A Multidimensional Approach to the Market Economy. Psychology Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780415238571.

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- Lex Heerma van Voss; Els Hiemstra-Kuperus; Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk, eds. (2010). "The Long Globalization and Textile Producers in India". The Ashgate Companion to the History of Textile Workers, 1650–2000. Ashgate Publishing. p. 255. ISBN 9780754664284.

- Boyajian, James C. (2008). Portuguese Trade in Asia Under the Habsburgs, 1580–1640. JHU Press. p. 51. ISBN 9780801887543. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Richards 1996, p. 20.

- Eaton, Richard M. (31 July 1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- Richards 1996, p. 202.

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Khandker, Hissam (31 July 2015). "Which India is claiming to have been colonised?". The Daily Star (Op-ed). Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Raychaudhuri, Tapan (1983). The Cambridge Economic History of India, II: The mid-eighteenth-century background. Cambridge University Press. p. 17.

- Branko, Milanovic; Peter H., Lindert; Jeffrey G., Williamson (November 2007). "Measuring ancient inequality". World Bank. World Bank: 1–88. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- Kirti N. Chaudhuri (2006). The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company: 1660–1760. Cambridge University Press. p. 253. ISBN 9780521031592.

- P. J. Marshall (2006). Bengal: The British Bridgehead: Eastern India 1740-1828. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780521028226.

- Kumar, D (1983). The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 2, C.1757-c.1970. CUP. p. 296. ISBN 085802070X. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Maddison, Angus (2007), Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD. Essays in Macro-Economic History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1, p. 382, table A.7

- Jeffrey G. Williamson (2011). Trade and Poverty: When the Third World Fell Behind. MIT Press. p. 91.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2005). "Cotton textiles and the great divergence: Lancashire, India and shifting competitive advantage, 1600–1850" (PDF). International Institute of Social History. Department of Economics, University of Warwick. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- Sashi Sivramkrishna (13 September 2016). In Search of Stability: Economics of Money, History of the Rupee. Taylor & Francis. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-351-99749-2.

- Robb 2004, pp. 131–34.

- Peers 2006, pp. 48–49

- Farnie 1979, p. 33

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 252. ISBN 9781107507180.

- Data table in Maddison A (2007), Contours of the World Economy I-2030AD, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199227204

- de Vries, Jan (2012). "Review". American Historical Review. 117 (5): 1534.

- Clingingsmith, David; Williamson, Jeffrey G. "India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries" (PDF). Trinity College Dublin. Harvard University. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- Madison, Angus (2001). The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective. OECD. ISBN 978-92-64-18998-0. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- Bagchi, Amiya (1976). "Deindustrialization in India in the Nineteenth Century: Some Theoretical Implications". Journal of Development Studies. 12 (October): 135–64.

- Indrajit Ray (November 2009). "Identifying the woes of the cotton textile industry in Bengal: Tales of the nineteenth century". The Economic History Review. 62 (4): 857–92. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00444.x. JSTOR 27771525.

- Junie T. Tong (15 April 2016). Finance and Society in 21st Century China: Chinese Culture Versus Western Markets. CRC Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-317-13522-7.

- The Islamic World: Abba - Hist. 1. Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-19-516520-3.

- Indrajit Ray (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757-1857). Routledge. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Shombit Sengupta, Bengals plunder gifted the British Industrial Revolution, The Financial Express, 8 February 2010

- James Cypher (2014). The Process of Economic Development. Routledge.

- Paul Bairoch (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. p. 89.

- Henry Yule, A. C. Burnell (2013). Hobson-Jobson: The Definitive Glossary of British India. Oxford University Press. p. 20.

- Giorgio Riello, Tirthankar Roy (2009). How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500–1850. Brill Publishers. p. 174.

- Griffin, Emma. "Why was Britain first? The industrial revolution in global context". Retrieved 9 March 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2009). "Indian GDP before 1870: Some preliminary estimates and a comparison with Britain" (PDF). Warwick University. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Hitchcock, John. "Population of Great Britain & Ireland 1570–1931". GenDocs. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Frank, Andre Gunder; Denemark, Robert A. (2015). Reorienting the 19th Century: Global Economy in the Continuing Asian Age. Routledge. pp. 83–85.

- Paul Bairoch (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. pp. 95–104.

- Jochnick, Chris; Preston, =Fraser A. (2006). Sovereign Debt at the Crossroads: Challenges and Proposals for Resolving the Third World Debt Crisis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516801-3.

- Paul Bairoch (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. p. 104.

- Fernand Braudel (1982). Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century. 3. University of California Press. p. 534.

- John M. Hobson (2004). The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–76.

- "Indian Ordnance Factories: Gun and Shell Factory". Ofb.gov.in. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- B. R. Tomlinson, The economy of modern India, 1860–1970 (1996)

- Judith Brown, Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy (Oxford University Press, 1994) p. 12

- B. R. Tomlinson, The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970 (1996) p. 5

- F. H. Brown and B. R. Tomlinson, "Tata, Jamshed Nasarwanji (1839–1904)", in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) accessed 28 Jan 2012 doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36421

- Vinay Bahl, "The Emergence of Large-Scale Steel Industry in India Under British Colonial Rule, 1880–1907," Indian Economic and Social History Review, (Oct 1994) 31#4 pp. 413–60

- Ian J. Kerr (2007). Engines of change: the railroads that made India. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98564-6.

- Derbyshire 1987, pp. 521–45.

- R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-81-230-1254-4.

- Thorner, Daniel (2005). "The pattern of railway development in India". In Kerr, Ian J. (ed.). Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 80–96. ISBN 978-0-19-567292-3.

- Babu, T. Stanley (2004). A shining testimony of progress. Indian Railways. Indian Railway Board. p. 101.

- Hurd, John (2005). "Railways". In Kerr, Ian J. (ed.). Railways in Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 147–172–96. ISBN 978-0-19-567292-3.

- R.R. Bhandari (2005). Indian Railways: Glorious 150 years. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 44–52. ISBN 978-81-230-1254-4.

- Daniel R. Headrick, The tentacles of progress: technology transfer in the age of imperialism, 1850–1940, (1988) pp. 8–82