Gandhara grave culture

The Gandhara grave culture, also called Swat culture, emerged c. 1700 BCE in the upper Indus Valley and spread to the Valleys of Swat, Dir, Kunar, Chitral, and Peshawar, flourishing until c. 500 BCE.[1] The core region was in Middle Swat River although it is used the name Gandhara, which lies in modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. It has been regarded as a token of the Indo-Aryan migrations, but has also been explained by local cultural continuity. Middle Swat River burials were first commented by Chiara Silvi Antonini and Giorgio Stacul in 1972, but recent studies and fieldworks have changed the chronology of this archaeological phase naming it Swat Protohistoric Graveyards Complex between c. 1200 and 800 BCE, claiming that there are no burials with these features after 800 BCE.[2]

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Palaeolithic (2,500,000–250,000 BC) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Neolithic (10,800–3300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chalcolithic (3500–1500 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – AD 1206) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1526)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial states (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Periods of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

National histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Specialised histories

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Location and characteristics

Relevant finds, artifacts found primarily in graves, were distributed along the banks of the Swat and Dir rivers in the north, Taxila in the southeast, along the Gomal River to the south. Simply made terracotta figurines were buried with the pottery, and other items are decorated with simple dot designs.[3]

Re-evaluation of the findings suggests this so-called Gandhara Grave Culture was actually a burial tradition, spread across a wide geographical area, rather than a specific culture.[4] There are more than thirty cemeteries of this tradition found in Swat and surrounding valleys of Dir, Buner, Malakand, Chitral, and in the Vale of Peshawar to the south, featuring cist graves, where large stone slabs were used to line the pit, above which another large flat stone was laid forming a roof over them, related settlement sites were also found which helped to know more of this people's life and death.[5]

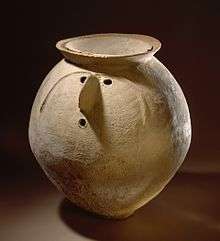

Anthropomorphic urns with cremation remains were not frequently found in graves, and most common pottery within these graves is Burnished Grey Ware and Burnished Red Ware, along with human terracotta figurines, however later graves are more elaborate featuring more items, various graves with horse remains and horse furniture were also reported.[6]

Origins

The Gandhara grave culture may be an artifact of the Indo-Aryan migrations, but it may also be explained by regional cultural continuity.

Single burials are characteristic of the early phase, between c. 1700 and 1400 BCE, along with bronze objects and pottery within the graves. Cremation is distinctive in the middle phase, c. 1400 to 1000 BCE, and ashes were laid in large jars, often bearing a human-like face design, this jars were then placed frequently in circular pits, surrounded by objects of bronze, gold and pottery. Multiple burials and fractional remains are found in the late phase, c. 1000 to 500 BCE, along with iron objects, coeval with the beginning of urban centers of Taxila and Charsadda.[7]

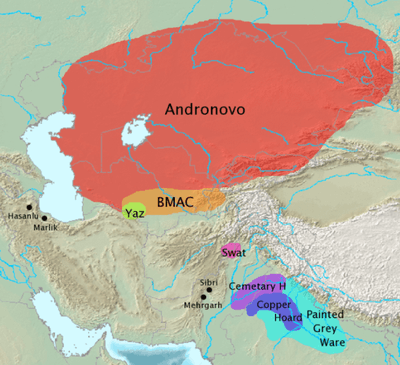

Indo-Aryan migrations

The polished black-gray pottery of Gandhara grave culture during the Ghalegay IV period, considered to run from 1700-1400 BCE, has been associated with that of other BMAC sites like Dashly in Afghanistan, Tepe Hissar and Tureng Teppe. According to Asko Parpola, the presence of black-red pottery also suggests links with Cemetery H culture in Punjab. The burial of bodies, the metal pins used got fastening clothes and the terracotta statuettes of females, says Parpola, are similar to those found to the BMAC. The graves during the Ghalegay V period, considered to run from 1400-1000 BCE, are connected with those in Vakhsh and Beshkent Valley. Parpola adds that these graves represent a mix of the practices found in northern Bactrian portion of BMAC during the period of 1700-1400 BCE and the Fedorovo Andronovo culture.[8]

According to Upinder Singh, the Gandhara grave culture is similar to the one in the Ghalegay caves during their V, VI and VII phases.[9] Rajesh Kochhar says it may be associated with early Indo-Aryan speakers as well as the Indo-Aryan migration into the Indian Subcontinent,[10] which came from the Bactria–Margiana region. According to Kochhar, the Indo-Aryan culture fused with indigenous elements of the remnants of the Indus Valley Civilization (OCP, Cemetery H) and gave rise to the Vedic Civilization.[10]

Cultural continuity

Asko Parpola argues that the Gandhara grave culture is "by no means identical with the Bronze Age Culture of Bactria and Margiana".[11] According to Tusa, the Gandhara grave culture and its new contributions are "in line with the cultural traditions of the previous period".[12] According to Parpola, in the centuries preceding the Gandhara culture, during the Early Harappan period (roughly 3200–2600 BCE), similarities in pottery, seals, figurines, ornaments etc. document intensive caravan trade between the Indian Subcontinent and Central Asia and the Iranian plateau.[13] Tusa remarks that

... to attribute a historical value to [...] the slender links with northwestern Iran and northern Afghanistan [...] is a mistake[, since] it could well be the spread of particular objects and, as such, objects that could circulate more easily quite apart from any real contacts.[12]

According to Kennedy, who argues for a local cultural continuity, the Gandhara grave culture people shared biological affinities with the population of Neolithic Mehrgarh. This suggests a "biological continuum" between the ancient populations of Timargarha and Mehrgarh.[14] This is contested by Elena E. Kuz'mina, who notes remains that are similar to some from Central Asian populations.[15]

Antonini,[16] Stacul and other scholars argue that this culture is also not related to the Bishkent culture and Vakhsh culture of Tajikistan.[17] However, E. Kuz'mina argues the opposite on the basis of both archaeology and the human remains from the separate cultures.[18]

Genetics

Narasimhan et al. 2018 analyzed DNA of 362 ancient skeletons from Central and South Asia, including those from the Iron Age grave sites discovered in the Swat valley of Pakistan (between 1200 BCE and 1 CE from Aligrama, Barikot, Butkara, Katelai, Loe Banr, and Udegram). According to them, "there is no evidence that the main BMAC population contributed genetically to later South Asians", and that "Indus Periphery-related people are the single most important source of ancestry" in Indus Valley Civilization and South Asia. They further state that the Swat valley grave DNA analysis provides further evidence of "connections between [Central Asian] Steppe population and early Vedic culture in India".[19]

References

- Coningham, Robin, and Mark Manuel, (2008). "Kashmir and the Northwest Frontier", Asia, South, in Encyclopedia of Archaeology 2008, Elsevier, p. 740.

- Olivieri, Luca M., (2019). "The Early-Historic Funerary Monuments of Butkara IV: New Evidence on a Forgotten Excavation in Outer Gandhara", in Rivista Degli Studi Orientali, Nuova Serie, Volume XCII, Fasc. 1-2, Sapienza Universitá di Roma, Instituto Italiano di Studi Orientali, Pisa-Rome, p. 231.

- Coningham, Robin, and Mark Manuel, (2008). "Kashmir and the Northwest Frontier", Asia, South, in Encyclopedia of Archaeology 2008, Elsevier, p. 740.

- Coningham, Robin, and Ruth Young, (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE - 200 CE, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 287.

- Coningham, Robin, and Ruth Young, (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE - 200 CE, Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 290 and 293.

- Coningham, Robin, and Mark Manuel, (2008). "Kashmir and the Northwest Frontier", Asia, South, in (ed.) Deborah M. Pearsall, Encyclopedia of Archaeology, Elsevier, p. 740.

- Coningham, Robin, and Ruth Young, (2015). The Archaeology of South Asia: From the Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE - 200 CE, Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 293.

- Parpola, Asko, (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press, p. 80-81.

- Singh, Upinder, (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education, Delhi, p. 212.

- Kochhar 2000, pp. 185-186.

- Parpola 1993, p. 54.

- Tusa 1977, p. 690-692.

- Asko Parpola, Study of the Indus Script, May 2005 p. 2f.

- Kenneth A.R. Kennedy. 2000, God-Apes and Fossil Men: Palaeoanthropology of South Asia Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 339.

- "The origin of the Indo-iranians, volume 3" Elena E. Kuz'mina p. 318

- Antonini 1973.

- Bryant 2001.

- E. Kuz'mina, "The origin of the Indo-Iranians, volume 3" (2007)

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M.; Patterson, Nick J.; Moorjani, Priya; Lazaridis, Iosif; Mark, Lipson; Mallick, Swapan; Rohland, Nadin; Bernardos, Rebecca; Kim, Alexander M. (31 March 2018). "The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia". bioRxiv: 292581. doi:10.1101/292581.

Sources

- Bryant, Edwin (2001), The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513777-9

- Kochhar, Rajesh (2000), The Vedic People: Their History and Geography, Sangam BooksCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Müller-Karpe, Hermann (1983), Jungbronzezeitlich-früheisenzeitliche Gräberfelder der Swat-Kultur in Nord-Pakistan, Beck, ISBN 3406301541

- Parpola, Asko (1993), "Margiana and the Aryan Problem", International Association for the Study of the Cultures of Central Asia Information Bulletin 19:41-62

- Tusa, Sebastiano (1977), "The Swat Valley in the 2nd and 1st Millennia BC: A Question of Marginality", South Asian Archaeology 6:675-695