Colonial India

Colonial India was the part of the Indian subcontinent that was under the jurisdiction of European colonial powers during the Age of Discovery. European power was exerted both by conquest and trade, especially in spices.[1][2] The search for the wealth and prosperity of India led to the colonization of the Americas by Christopher Columbus in 1492. Only a few years later, near the end of the 15th century, Portuguese sailor Vasco da Gama became the first European to re-establish direct trade links with India since Roman times by being the first to arrive by circumnavigating Africa (c. 1497–1499). Having arrived in Calicut, which by then was one of the major trading ports of the eastern world,[3] he obtained permission to trade in the city from Saamoothiri Rajah. The next to arrive were the Dutch, with their main base in Ceylon. Their expansion into India was halted, after their defeat in the Battle of Colachel by the Kingdom of Travancore, during the Travancore-Dutch War.

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1668–1954 |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

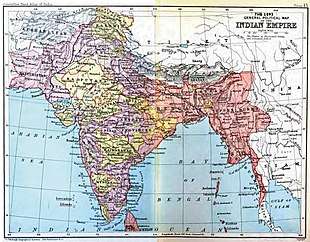

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India | 1947 |

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Palaeolithic (2,500,000–250,000 BC) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Neolithic (10,800–3300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chalcolithic (3500–1500 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3300–1300 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1500–200 BC)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Middle Kingdoms (230 BC – AD 1206) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1526)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial states (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Periods of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

National histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Specialised histories

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Trading rivalries among the seafaring European powers brought other European powers to India. The Dutch Republic, England, France, and Denmark-Norway all established trading posts in India in the early 17th century. As the Mughal Empire disintegrated in the early 18th century, and then as the Maratha Empire became weakened after the third battle of Panipat, many relatively weak and unstable Indian states which emerged were increasingly open to manipulation by the Europeans, through dependent Indian rulers.

In the later 18th century Great Britain and France struggled for dominance, partly through proxy Indian rulers but also by direct military intervention. The defeat of the formidable Indian ruler Tipu Sultan in 1799 marginalised the French influence. This was followed by a rapid expansion of British power through the greater part of the Indian subcontinent in the early 19th century. By the middle of the century the British had already gained direct or indirect control over almost all of India. British India, consisting of the directly-ruled British presidencies and provinces, contained the most populous and valuable parts of the British Empire and thus became known as "the jewel in the British crown".

India, during its colonial era, was a founding member of the League of Nations, a participating nation in the Summer Olympics in 1900, 1920, 1928, 1932, and 1936, and a founding member of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945.[4] In 1947, India gained its independence and was partitioned into the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan, the latter of which was created as a homeland for colonial India's Muslims.[5][6][7]

Portuguese

Long after the decline of the Roman Empire's sea-borne trade with India, the Portuguese were the next Europeans to sail there for the purpose of trade, first arriving by ship in May 1498. The closing of the traditional trade routes in western Asia by the Ottoman Empire, and rivalry with the Italian states sent Portugal in search of an alternate sea route to India. The first successful voyage to India was by Vasco da Gama in 1498, when after sailing around the Cape of Good Hope he arrived in Calicut, now in Kerala. Having arrived there, he obtained from Saamoothiri Rajah permission to trade in the city. The navigator was received with traditional hospitality, but an interview with the Saamoothiri (Zamorin) failed to produce any definitive results. Vasco da Gama requested permission to leave a factor behind in charge of the merchandise he could not sell; his request was refused, and the king insisted that Gama should pay customs duty like any other trader, which strained their relations.

Though Portugal's presence in India initially started in 1498, their colonial rule lasted from 1505 until 1961. The Portuguese Empire established the first European trading centre at Quilon(Kollam) in 1502. It is believed that the colonial era in India started with the establishment of this Portuguese trading center at Quilon.[8] In 1505, King Manuel I of Portugal appointed Dom Francisco de Almeida as the first Portuguese viceroy in India, followed in 1509 by Dom Afonso de Albuquerque. In 1510, Albuquerque conquered the city of Goa, which had been controlled by Muslims. He inaugurated the policy of marrying Portuguese soldiers and sailors with local Indian girls, the consequence of which was a great miscegenation in Goa and other Portuguese territories in Asia. Another feature of the Portuguese presence in India was their will to evangelise and promote Catholicism. In this, the Jesuits played a fundamental role, and to this day the Jesuit missionary Saint Francis Xavier is revered among the Catholics of India.

The Portuguese established a chain of outposts along India's west coast and on the island of Ceylon in the early 16th century. They built the St. Angelo Fort at Kannur to guard their possessions in North Malabar. Goa was their prized possession and the seat of Portugal's viceroy. Portugal's northern province included settlements at Daman, Diu, Chaul, Baçaim, Salsette, and Mumbai. The rest of the northern province, with the exception of Daman and Diu, was lost to the Maratha Empire in the early 18th century.

In 1661, Portugal was at war with Spain and needed assistance from England. This led to the marriage of Princess Catherine of Portugal to Charles II of England, who imposed a dowry that included the insular and less inhabited areas of southern Bombay while the Portuguese managed to retain all the mainland territory north of Bandra up to Thana and Bassein. This was the beginning of the English presence in India.

Evolution of Portuguese possessions in the Indian subcontinent.

Evolution of Portuguese possessions in the Indian subcontinent.- Vasco da Gama lands at Calicut, 20 May 1498 CE.

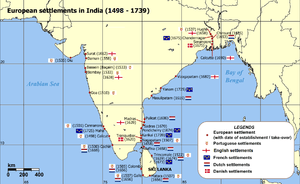

European settlements in India (1501–1739).

European settlements in India (1501–1739).

Dutch

The Dutch East India Company established trading posts on different parts along the Indian coast. For some while, they controlled the Malabar southwest coast (Pallipuram, Cochin, Cochin de Baixo/Santa Cruz, Quilon (Coylan), Cannanore, Kundapura, Kayamkulam, Ponnani) and the Coromandel southeastern coast (Golkonda, Bhimunipatnam, Pulicat, Parangippettai, Negapatnam) and Surat (1616–1795). They conquered Ceylon from the Portuguese. The Dutch also established trading stations in Travancore and coastal Tamil Nadu as well as at Rajshahi in present-day Bangladesh, Hugli-Chinsura, and Murshidabad in present-day West Bengal, Balasore (Baleshwar or Bellasoor) in Odisha, and Ava, Arakan, and Syriam in present-day Myanmar (Burma). However, their expansion into India was halted, after their defeat in the Battle of Colachel by the Kingdom of Travancore, during the Travancore-Dutch War. The Dutch never recovered from the defeat and no longer posed a large colonial threat to India.[9][10]

Ceylon was lost at the Congress of Vienna in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, where the Dutch having fallen subject to France, saw their colonies raided by Britain. The Dutch later became less involved in India, as they had the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

English and British India

Rivalry with the Netherlands

At the end of the 16th century, England and the United Netherlands began to challenge Portugal's monopoly of trade with Asia, forming private joint-stock companies to finance the voyages: the English (later British) East India Company, and the Dutch East India Company, which were chartered in 1600 and 1602 respectively. These companies were intended to carry on the lucrative spice trade, and they focused their efforts on the areas of production, the Indonesian archipelago and especially the "Spice Islands", and on India as an important market for the trade. The close proximity of London and Amsterdam across the North Sea, and the intense rivalry between England and the Netherlands, inevitably led to conflict between the two companies, with the Dutch gaining the upper hand in the Moluccas (previously a Portuguese stronghold) after the withdrawal of the English in 1622, but with the English enjoying more success in India, at Surat, after the establishment of a factory in 1613.

The Netherlands' more advanced financial system[11] and the three Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th century left the Dutch as the dominant naval and trading power in Asia. Hostilities ceased after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the Dutch prince William of Orange ascended the English throne, bringing peace between the Netherlands and England. A deal between the two nations left the more valuable spice trade of the Indonesian archipelago to the Netherlands and the textiles industry of India to England, but textiles overtook spices in terms of profitability, so that by 1720, in terms of sales, the English company had overtaken the Dutch.[11] The English East India Company shifted its focus from Surat—a hub of the spice trade network—to Fort St. George.

East India Company

In 1757 Mir Jafar, the commander in chief of the army of the Nawab of Bengal, along with Jagat Seth, and some others, secretly connived with the British, asking support to overthrow the Nawab in return for trade grants. The British forces, whose sole duty until then was guarding Company property, were numerically inferior to the Bengali armed forces. At the Battle of Plassey on 23 June 1757, fought between the British under the command of Robert Clive and the Nawab, Mir Jafar's forces betrayed the Nawab and helped defeat him. Jafar was installed on the throne as a British subservient ruler.[12] The battle transformed British perspective as they realised their strength and potential to conquer smaller Indian kingdoms and marked the beginning of the imperial or colonial era in South Asia.

British policy in Asia during the 19th century was chiefly concerned with expanding and protecting its hold on India, viewed as its most important colony and the key to the rest of Asia.[14] The East India Company drove the expansion of the British Empire in Asia. The company's army had first joined forces with the Royal Navy during the Seven Years' War, and the two continued to cooperate in arenas outside India: the eviction of Napoleon from Egypt (1799), the capture of Java from the Netherlands (1811), the acquisition of Singapore (1819) and Malacca (1824), and the defeat of Burma (1826).[15]

From its base in India, the company had also been engaged in an increasingly profitable opium export trade to China since the 1730s. This trade helped reverse the trade imbalances resulting from the British imports of tea, which saw large outflows of silver from Britain to China. In 1839, the confiscation by the Chinese authorities at Canton of 20,000 chests of opium led Britain to attack China in the First Opium War, and the seizure by Britain of the island of Hong Kong, at that time a minor settlement.[16]

The British had direct or indirect control over all of present-day India before the middle of the 19th century. In 1857, a local rebellion by an army of sepoys escalated into the Rebellion of 1857, which took six months to suppress with heavy loss of life on both sides, although the loss of British lives is in the range of a few thousand, the loss on the Indian side was in the hundreds of thousands.[18] The trigger for the Rebellion has been a subject of controversy. The resistance, although short-lived, was triggered by British East India Company attempts to expand its control of India. According to Olson, several reasons may have triggered the Rebellion. For example, Olson concludes that the East India Company's attempt to annex and expand its direct control of India, by arbitrary laws such as Doctrine of Lapse, combined with employment discrimination against Indians, contributed to the 1857 Rebellion.[19] The East India Company officers lived like princes, the company finances were in shambles, and the company's effectiveness in India was examined by the British crown after 1858. As a result, the East India Company lost its powers of government and British India formally came under direct British rule, with an appointed Governor-General of India. The East India Company was dissolved the following year in 1858. A few years later, Queen Victoria took the title of Empress of India.[20]

India suffered a series of serious crop failures in the late 19th century, leading to widespread famines in which at least 10 million people died. Responding to earlier famines as threats to the stability of colonial rule, the East India Company had already begun to concern itself with famine prevention during the early colonial period.[21] This greatly expanded during the Raj, in which commissions were set up after each famine to investigate the causes and implement new policies, which took until the early 1900s to have an effect.[22]

The slow but momentous reform movement developed gradually into the Indian Independence Movement. During the years of World War I, the hitherto bourgeois "home-rule" movement was transformed into a popular mass movement by Mahatma Gandhi, a pacifist. Revolutionaries such as Bagha Jatin, Khudiram Bose, Bhagat Singh, Chandrashekar Azad, Surya Sen, Subhas Chandra Bose were not against use of violence to oppose the British rule. The independence movement attained its objective with the independence of Pakistan and India on 14 and 15 August 1947 respectively.

Conservative elements in England consider the independence of India to be the moment that the British Empire ceased to be a world power, following Curzon's dictum that, "[w]hile we hold on to India, we are a first-rate power. If we lose India, we will decline to a third-rate power."

French

Following the Portuguese, English, and Dutch, the French also established trading bases in India. Their first establishment was in Pondicherry on the Coromandel Coast in southeastern India in 1674. Subsequent French settlements were Chandernagore in Bengal, northeastern India in 1688, Yanam in Andhra Pradesh in 1723, Mahe in 1725, and Karaikal in 1739. The French were constantly in conflict with the Dutch and later on mainly with the British in India. At the height of French power in the mid-18th century, the French occupied large areas of southern India and the area lying in today's northern Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. Between 1744 and 1761, the British and the French repeatedly attacked and conquered each other's forts and towns in southeastern India and in Bengal in the northeast. After some initial French successes, the British decisively defeated the French in Bengal in the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and in the southeast in 1761 in the Battle of Wandiwash, after which the British East India Company was the supreme military and political power in southern India as well as in Bengal. In the following decades, it gradually increased the size of the territories under its control. The enclaves of Pondichéry, Karaikal, Yanam, Mahé, and Chandernagore were returned to France in 1816 and were integrated with the Republic of India in 1954.

Dano-Norwegian

Denmark–Norway held colonial possessions in India for more than 200 years, but the Danish presence in India was of little significance to the major European powers as they presented neither a military nor a mercantile threat.[23] Denmark–Norway established trading outposts in Tranquebar, Tamil Nadu (1620), Serampore, West Bengal (1755), Calicut, Kerala (1752) and the Nicobar Islands (1750s). At one time, the main Danish and Swedish East Asia companies together imported more tea to Europe than the British did. Their outposts lost economic and strategic importance, and Tranquebar, the last Dano-Norwegian outpost, was sold to the British on 16 October 1868.

Other external powers

The Spanish were briefly given territorial rights to India by Pope Alexander VI on 25 September 1493 by the bull Dudum siquidem before these rights were removed by the Treaty of Tordesillas less than one year later. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands were briefly occupied by the Japanese Empire during World War II.[24][25][26]

The Swedish East India Company briefly possessed a factory in Parangipettai.[27]

Wars

.jpg)

The wars that took place involving the British East India Company or British India during the Colonial era:

- Anglo-Mysore Wars

- First Anglo-Maratha War

- Second Anglo-Maratha War

- Third Anglo-Maratha War

- First Anglo-Sikh War

- Second Anglo-Sikh War

- Gurkha War

- Burmese Wars

- First Opium War

- India's First War of Independence

- Second Opium War

- First Anglo-Afghan War

- Second Anglo-Afghan War

- Third Anglo-Afghan War

- World War I, see List of Indian divisions in World War I, Bombardment of Madras

- World War II

See also

- Ancient India

- Indian empires

- British Raj

- List of Indian Princely States

- Arakkal Kingdom

- Hyderabad State

- Kingdom of Mysore

- Kingdom of Travancore

- Rajput States

- Kingdom of Calicut

Notes

- Corn, Charles (1998). The Scents of Eden: A Narrative of the Spice Trade. Kodansha. pp. xxi–xxii. ISBN 978-1-56836-202-1.

The ultimate goal of the Portuguese, as with the nations that followed them, was to reach the source of the fabled holy trinity of spices ... while seizing the vital centers of international trade routes, thus destroying the long-standing Muslim control of the spice trade. European colonization of Asia was ancillary to this purpose.

- Donkin, Robin A. (2003). Between East and West: The Moluccas and the Traffic in Spices Up to the Arrival of Europeans. Diane Publishing Company. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 978-0-87169-248-1.

What drove men to such extraordinary feats ... gold and silver in easy abundance ... and, perhaps more especially, merchandise that was altogether unavailable in Europe—strange jewels, orient pearls, rich textiles, and animal and vegetable products of equatorial provenance ... The ultimate goal was to obtain supplies of spices at source and then to meet demand from whatever quarter.

- "The Land That Lost Its History". Time. 20 August 2001. Archived from the original on 13 September 2001.

- Mansergh, Nicholas, Constitutional relations between Britain and India, London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, p. xxx, retrieved 19 September 2013 Quote: "India Executive Council: Sir Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar, Sir Firoz Khan Noon and Sir V. T. Krishnamachari served as India's delegates to the London Commonwealth Meeting, April 1945, and the U.N. San Francisco Conference on International Organisation, April–June 1945."

- Fernandes, Leela (2014). Routledge Handbook of Gender in South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-90707-7.

Partition of colonial India in 1947 – forming two nation-states, India and Pakistan, at the time of its independence from almost two centuries of British rule – was a deeply violent and gendered experience.

- Trivedi, Harish; Allen, Richard (2000). Literature and Nation. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-21207-6.

In this introductory section I want to touch briefly on four aspects of this social and historic context for a reading of Sunlight on a Broken Column: the struggle for independence; communalism and the partition of colonial India into independent India and East and West Pakistan; the social structure of India; and the specific situation of women.

- Gort, Jerald D.; Jansen, Henry; Vroom, Hendrik M. (2002). Religion, Conflict and Reconciliation: Multifaith Ideals and Realities. Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-1166-3.

Partition was intended to create a homeland for Indian Muslims, but this was far from the case; Indian Muslims are not only divided into three separate sections, but the number of Muslims in India--for whom the Muslim homeland was meant--still remains the highest of all three sections.

- "The ugly and good side of conversions in South Asia". NewsIn Asia. 10 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- Koshy, M.O. (1989). The Dutch Power in Kerala, 1729–1758. Mittal Publications. p. 61. ISBN 978-81-7099-136-6.

- http://mod.nic.in Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine 9th Madras Regiment

- Ferguson 2004, p. 19.

- Wolpert, Stanley (1989). A New History of India (3rd ed.), p. 180. Oxford University Press.

- Washbrook, D. A. (2001). "India, 1818–1860: The Two Faces of Colonialism". In Porter, Andrew (ed.). Oxford History of the British Empire: The Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-19-924678-6.

- Olson, p. 478.

- Porter, p. 401.

- Olson, p. 293.

- Ilina, Anastasiia. "An Introduction to Vasily Vereshchagin in 10 Paintings". Culture Trip. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- Ramesh, Randeep (24 August 2007). "India's secret history: 'A holocaust, one where millions disappeared...'". The Guardian.

- Olson, p.653

- Olson, p. 568

- Ahuja, Ravi (26 July 2016). "State formation and 'famine policy' in early colonial south India". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 39 (4): 351–380. doi:10.1177/001946460203900402.

- Marshall, pp. 133–34.

- Rasmussen, Peter Ravn (1996). "Tranquebar: The Danish East India Company 1616–1669". University of Copenhagen. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "The capture of Andaman Islands, March 1942". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- Dasgupta Red Sun over Black Water pp. 50–51

- Mathur Kala Pani p. 248; Iqbal Singh The Andaman Story pp. 241–42

- "Porto Novo". Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish). Retrieved 23 September 2019.

References

- Prasenjit K. Basu " Asia Reborn: A Continent Rises from the Ravages of Colonialism and War to a New Dynamism", Publisher: Aleph Book Company

- Brian, Mac Arthur (1996) The Penguin Book of Historic Speeches ed. Penguin Books.

- Buckland, C.E. Dictionary of Indian Biography (1906) 495pp full text

- Kachru, Braj (1983) The Indianization of English, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Moss, Peter (1999) Oxford History for Pakistan, a revised and expanded version of Oxford History Project Book Three Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ferguson, Niall (2004). Empire. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02329-5. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Olson, James (1996). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29366-5. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Marshall, PJ (1996). The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00254-7. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Porter, Andrew (1998). The Nineteenth Century, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume III. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924678-6. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Riddick, John F. The History of British India: A Chronology (2006) excerpt

- Riddick, John F. Who Was Who in British India (1998); 5000 entries excerpt

Further reading

- Andrada (undated). The Life of Dom John de Castro: The Fourth Vice Roy of India. Jacinto Freire de Andrada. Translated into English by Peter Wyche. (1664). Henry Herrington, New Exchange, London. Facsimile edition (1994) AES Reprint, New Delhi. ISBN 81-206-0900-X

- Crosthwaite, Charles (1905). . The Empire and the Century. London: John Murray. pp. 621–650.

- Herbert, William; William Nichelson; Samuel Dunn (1791). A New Directory for the East-Indies. Gilbert & Wright, London.

- Panikkar, K. M. (1953). Asia and Western Dominance, 1498–1945, by K.M. Panikkar. London: G. Allen and Unwin.

- Panikkar, K. M. 1929: Malabar and the Portuguese: being a history of the relations of the Portuguese with Malabar from 1500 to 1663

- Priolkar, A. K. The Goa Inquisition (Bombay, 1961).

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Colonial India. |