Sukkur

Sukkur

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Metropolis | ||

View of Sukkur's iconic British-era Lansdowne Bridge and the modern Ayub Bridge, which both span the Indus River and offer access to the city of Rohri | ||

| ||

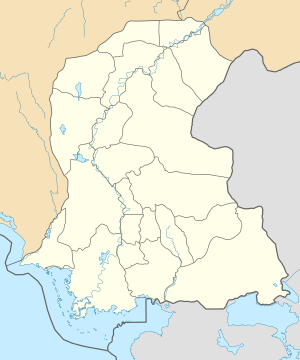

Sukkur Location of Sukkur  Sukkur Sukkur (Pakistan) | ||

| Coordinates: 27°42′22″N 68°50′54″E / 27.70611°N 68.84833°ECoordinates: 27°42′22″N 68°50′54″E / 27.70611°N 68.84833°E | ||

| Country | Pakistan | |

| Province | Sindh | |

| District | Sukkur District | |

| Government | ||

| • Type | Municipal Corporation | |

| • Mayor of Sukkur | Arsalan Shaikh | |

| • Deputy Mayor of Sukkur | Tariq Chauhan | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 5,165 km2 (1,994 sq mi) | |

| Elevation | 67 m (220 ft) | |

| Population (2017) | ||

| • Total | 499,900 | |

| • Density | 97/km2 (250/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) | |

| Calling code | 071 | |

| Number of towns | 4 | |

| Number of Union councils | 20 | |

| "About District". District Government Sukkur. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. | ||

Sukkur (Sindhi: سکر; Urdu: سکّھر) is a city in the Pakistani province of Sindh along the western bank of the Indus River, directly across from the historic city of Rohri. Sukkur is the third largest city in Sindh after Karachi and Hyderabad, and is 14th most populous city in Pakistan.[1] New Sukkur was established during the British era alongside the village of Sukkur. Sukkur's hill, along with the hill on the river island of Bukkur, form what is sometimes considered the "Gate of Sindh,"[2] in reference to the city's location along the frontier that separates the historical Sindhi heartland from the Saraiki-speaking regions to the north.

Etymology

The name Sukkur may derive from the Arabic word for "sugar," shakkar, in reference to the sugarcane fields that have historically been abundant in the region.[3] This may be an allusion to the relative prosperity of the region at the time. Others have suggested the name may derive from the word Sukh, derived from a Sindhi word for "comfort."[3]

History

.jpg)

The region around Sukkur has been inhabited for millennia. The ruins of Lakhueen-jo-daro, located near an industrial park on the outskirts of Sukkur,[4] date from the Mature Harappan period of the Indus Valley Civilisation, between 2600 BCE and 1900 BCE.[5]

"Old Sukkur" was initially a small village prior to the establishment of a military garrison in 1839. Sukkur was built on a low limestone ridge on the banks of the Indus River.[6] The city was once surrounded by groves of date palms that were traditionally believed to have grown from the discarded date-pits from Arab invaders in the 8th century.[6]

The village of Sukkur was directly across from the larger town of Rohri, which served as a busy port along the Indus by the 1200s, and was a major trading centre for agricultural produce.[7] An 86 foot tall minaret was built at Sukkur's shrine of Mir Masum Shah in 1607.[6]

British

Modern Sukkur, or New Sukkur, was built during British rule alongside what was once a small village directly across from the historic city of Rohri. The British established a military garrison here in 1839,[8] which was abandoned in 1845, though Sukkur continued to grow in importance as a trading center.[8] The Sukkur Municipality was constituted in 1862.[9]

Completed in 1889, Sukkur's Lansdowne Bridge connects the Sukkur to Rohri across the Indus, and was one of the first bridges to cross the river. The bridge made the journey between Karachi and Multan easier. The bridge was built with two large pylons rather than a series of pillars extending across the river - a cutting-edge design for such an expansive span.[3] The bridge was also made of metal, and features an unusual design.

The Sukkur Barrage (formally called Lloyd Barrage), built under the British Raj on the Indus River, controls one of the largest irrigation systems in the world. It was designed by Sir Arnold Musto KCIE, and constructed under the overall direction of Sir Charlton Harrison between 1923 and 1932. The 5,001 feet (1,524 m) long barrage is made of yellow stone and steel and can water nearly 10 million acres (40,000 km2) of farmland through its seven large canals.[10][11]

On the eve of the Partition of British India in 1947, Sukkur's old town was home to about 10,000 residents, while New Sukkur was home to 80,000.[3]

Modern

After the independence of Pakistan most of the city's Hindu population migrated to India though like much of Sindh, Sukkur did not experience the widespread rioting that occurred in Punjab and Bengal.[12] In all, less than 500 Hindu were killed in all of Sindh between 1947-48 as Sindhi Muslims largely resisted calls to turn against their Hindu neighbours.[13] Hindus did not flee Sukkur en masse until riots erupted in Karachi on 6 January 1948, which sowed fear in Sindh's Hindus despite the fact that the riots were local and regarded Sikh refugees from Punjab seeking refuge in Karachi.[12] The Muslim refugees from India settled in Sukkur.

The Sindh Industrial Trading Estate in Sukkur was established in 1950. The Ayub Bridge was built in 1962, and spans the Indus River alongside the British-era Landsdowne Bridge. The city suffered major flooding during the 2010 Pakistan floods which inundated large parts of the city.

Geography

The small Eocene limestone outcropping upon which Sukkur was founded is the most significant land deformation on the vast plains along the Indus Valley in Sindh and Punjab.[14] The outcropping is part of the "Jacobabad-Khairpur High" and Rohri Hills.[14] The outcropping, along with the similar outcropping on Bukkar Island are sometimes referred to as the "Sukkur Gorge," and has historically served as the traditional northern boundary of Sindh.[15]

Climate

| Sukkur | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sukkur's desert climate is characterised by very hot and hazy summers with dry and cool winters. Sukkur is known for its extremely hot summers, and was described as the hottest city in British India.[8] Wind speed is low throughout the year, and sunshine is abundant. Summer is very hot as the temperature can reach 50 °C (122 °F). Dry heat is experienced starting April to early June until the Monsoon season starts to arrive. Monsoons in Sukkur are not very wet, but bring high dew points, resulting in high heat indices. Monsoons recede by September, but it is not until late October that the short lived autumn season is experienced before the onset of the region's cool winters.[17]

Demography

Sukkur is the third largest city in Sindh after Karachi and Hyderabad, and is 14th most populous city in Pakistan.[18] The population of Sukkur is estimated to be 2,725,122 in 2015.

| Historical population | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The following were the first languages:[19][20]

- Sindhi: 74.07%

- Urdu: 13.82%

- Punjabi: 6.63%

- Pashto: 1.53%

- Baluchi: 1.47%

- Seraiki: 0.99%

- Others: 1.49% (mainly Memoni, Marwari, Gujarati, Bihari Brahui and Kachi)

Religion

According to the 1998 census, the breakdown of the population by religion is as following:[21]

- Islam: 96.13%

- Hinduism: 3.18%

- Christianity: 0.51%

- Ahmaddiya: 0.04%

- Others: 0.14%

Economy

Sukkur's economy is largely reliant upon the agricultural produce from northern Sindh's farms, and serves as a trading and processing centre for agricultural goods.[7] The city also once had a bustling shipbuilding industry.[3]

Sukkur is well-connected to the rest of Pakistan by road and rail, which in turn has attracted new industries such as chemical manufacturing, metalworking, and cement manufacturing.[7]

Agriculture

Sukkur had a large fertile and cultivable land area. During kharif, rice, bajra, cotton, tomatoes and peas are cultivated; whereas during rabi the main crops are wheat, barley, graham and melons. Sukkur is famous, world over, for its dates. Sukkur also has a large Riveraine forest along the course of the Indus. These tropical forests are found within the protective embankments on either side of the Indus. During 1997–98 the total area under forests was 510 km2 which yielded 55,000 cubic feet (1,600 m3) of timber and 27,000 cubic feet (760 m3) of firewood besides other mine products.[22][23]

Transportation

Road

The city will be connected to Multan by the under construction M-5 motorway, with onwards motorway connections to Lahore, Islamabad, and Peshawar. Sukkur will also be connected to Hyderabad by the M-6 motorway, with onwards connections to Karachi via the M-9 motorway. The M-5 and M-6 are being built as part of the wider China-Pakistan Economic Corridor.

Rail

Sukkur railway station serves as the city's main rail station. Passenger services are provided exclusively by Pakistan Railways. The city's station is serviced by the Jaffar Express that runs between Rawalpindi and Quetta, the Sukkur Express that runs between Karachi and Jacobabad, and the Akbar Express that runs between Quetta and Peshawar.

Air

Sukkur Airport, located 8 km outside of the city, is served by Pakistan International Airlines, with direct flights to Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad.

Administration

The city of Sukkur is the capital of Sukkur Division and also Divisional and district headquarters. Tehsils (Talukas) and contains many Union council.[24] Sukkur is home to one of three circuit benches of the Sindh High Court.[25]

Education

.jpg)

The Sukkur IBA University (previously Sukkur Institute of Business Administration or Sukkur IBA) is a business school founded in 1994. The institute is ranked 3rd among the five independent business schools of Pakistan included in the Higher Education Commission Pakistan Business School Ranking-2013).[26]

The Ghulam Muhammad Mahar Medical College is a constituent College of Shaheed Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Medical University.[27]

Notable people

- Mir Muhammad Masum Nami (d. 1606): Born to Shaikh-ul-Islam of Bhakkar of that time. He authored Tarikh-i-Masumi (aka Tarikh-i-Sind), a book on history of the Sindh province from the start of Muhammad Bin Qasim's arrival in Sindh to the beginning of 17th century. Mufradat-i-Nami was book written on medicine by him. He wrote a Diwan of poetry and versified the translation of legend of Sassi Pannu.[28]

- Hemu Kalani

- Abdul Hafeez Pirzada

- Syed Khurshid Shah, Leader of Opposition for National Assembly of Pakistan

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.citypopulation.de/Pakistan-100T.html

- ↑ Burton, Richard (1851). Sindh and the Races That Inhabit the Valley of the Indus. Asian Educational Services. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "History of Sukkur". Old Sukkur. Sindhi Association of India. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ↑ Hyder, Ali. "Brief Description of Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Sindh". Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ "Collecting samples from a Lakhueen-jo-daro trial trench". Archived from the original on 2008-04-22.

- 1 2 3 Ross, David (1883). The land of the five rivers and Sindh. Chapman and Hall. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 <Bowden, Rob (2004). Settlements of the Indus River. Heinemann-Raintree Library. ISBN 1403457182. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Hughes, Albert William (1876). A Gazetteer of the Province of Sind. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ "Sukkur". Britannica. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ Kiana, Khaleeq (16 July 2013). "Rule violations threaten Sukkur Barrage". dawn.com. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Sukku Barrage". Archived from the original on 2012-03-30.

- 1 2 Kumar, Priya (2 December 2016). Sindh, 1947 and Beyond. Routledge. pp. 773–789. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Chitkara, M. G. (1996). Mohajir's Pakistan. APH Publishing. ISBN 8170247462. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- 1 2 Shroder Jr., John F. (2002). Himalaya to the Sea: Geology, Geomorphology and the Quaternary. Routledge. ISBN 1134919778. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ Flint, Eric (2006). The Dance of Time. Baen Books. ISBN 1416509313. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ↑ "Climate Profile for Sukkur, Pakistan". MyWeather2. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- ↑ http://www.wunderground.com/history/airport/OPSK/2013/7/6/DailyHistory.html?MR=1

- ↑ http://www.citypopulation.de/Pakistan-100T.html

- ↑ PCO 1999, p. 34.

- ↑ "Sukkur census tables" (PDF). table 10, p. 34. Retrieved 2017-12-25.

- ↑ PCO 1999, p. 32.

- ↑ "Sukku at A Glance". sukkurcity.com. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Explore Pakistan". findpk.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Union Administrations of Taluka Sukkur". Archived from the original on 11 May 2006.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ : Higher Education Commission (HEC) ranking

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ↑ Nabi Hadi 1995.

Bibliography

- Dirk Collier (1 March 2016), The Great Mughals and their India, Hay House, Inc., p. 207, ISBN 978-9-38-454498-0

- Nabi Hadi (1995), Dictionary of Indo-Persian Literature, Abhinav Publications, p. 449, ISBN 978-8-17-017311-3

- James Wynbrandt (2009), A Brief History of Pakistan, Infobase Publishing, p. 71, ISBN 978-0-81-606184-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sukkur. |

- District Government Sukkur

- Ghulam Muhammad Maher Medical College, Sukkur

- ADB Report on Sukkur Barrage 2001

- An Overview of the History and Impacts of the Water Issue in Pakistan

- Pakistan Floods Situation Report, 26 July 2005