Sheikhupura

| Sheikhupura شیخُوپُور | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| |

Sheikhupura  Sheikhupura | |

| Coordinates: 31°42′40″N 73°59′16″E / 31.71111°N 73.98778°ECoordinates: 31°42′40″N 73°59′16″E / 31.71111°N 73.98778°E | |

| Country | Pakistan |

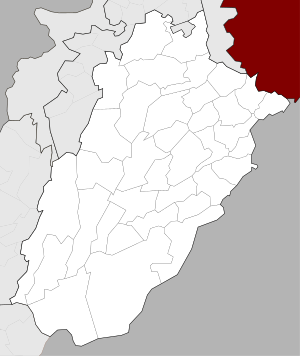

| Province | Punjab |

| District | Sheikhupura |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5,960 km2 (2,300 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 236 m (774 ft) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| Postal code | 39350 |

| Union council number | 51 |

Shekhupura (Urdu: شیخُوپُورہ , Punjabi: شیخُوپُور) is a city the Pakistani province of Punjab. Founded but the Mughal Emperor Jehangir in 1607, Sheikhupura is now the 17th largest city in Pakistan,[3] and is the headquarters of Sheikhupura District. The city is an industrial center, and satellite town, located about 38 km northwest of Lahore.[4]

Etymology

The region around Sheikhupura was previous known as Virk Garh, or "Virk Fort", in reference to the Jat tribe that inhabited the area.[5] The city, founded in 1607, was named by Jehangir himself - the city's first name is recorded in the Emperor's autobiography, the Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, in which he refers to the town as Jehangirabad.[6] The city then came to be known by its current name, which derives from Jehangir's nickname Sheikhu that was given to him by his mother, wife of Akbar the Great.[7]

History

Mughal

Mughal Emperor Jahangir laid the foundations of Sheikhupura in 1607 near the older town of Jandiala Sher Khan, an important provincial town during the early to middle Mughal era.[8] He also erected the nearby Hiran Minar, Sheikhpura's most renowned site, between 1607 and 1620 as a monument to his beloved pet deer, Mansiraj, at a time when the area served as a royal hunting ground for the Mughal Emperor.[9] Jehangir laid the foundation of the Sheikhupura Fort in 1607, which is situated in the city's centre.

Sikh

Following the collapse of Mughal authority, the city came under the control of the Bhatti tribe.[5] The tribe struggled to maintain control of the area, as bandits and Sikhs began encroaching upon the area. In 1797, the Durrani king Shah Zaman briefly seized the city and fortress during his campaign to capture Lahore.[10] The city's fort then was captured by the Sikh bandit, Inder Singh.

Sheikhupura was then captured from the Bhattis by the forces of Lehna Singh in 1799.[10] Sheikhupura thus came under the rule of the Sikh Sukherchakia Misl state under Lehna Singh's ally, Ranjit Singh, forcing the Bhatti tribe to retreat to Pindi Bhattian and Jalalpur.[5] Sheikhupura then changed hands several more times, before finally being captured by Ranjit Singh in 1808.[10]

Sheikhupura remained under suzerainty of the Sikh Empire until 1847, when the British seized control of the area. The British imprisoned the last Queen of the Sikh Empire, Maharani Jind Kaur, at the Sheikhpura Fort for ten months until 1848 before ultimately condemning her to exile abroad.[10]

British

Following establishment of British colonial rule, Bhatti possessions that had been seized by the Sikhs were restored.[5] The large area between the Chenab and Ravi rivers were initially consolidated into a single district with Sheikhupura serving as its first headquarters, until 1851.[5] The area around Sheikhupura attained District status in 1919,[5] with M.M.L. Karry serving as its first administrator.[11]

Partition

On the eve of the Partition of British India, Sikhs made up 19% of the district's population. Despite the area's Muslim majority, Sikhs had hoped that the boundary commission would award the area to India, given the proximity of Sheikhupura to the city of Nankana Sahib - revered as the birthplace of the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak.[12] The city was spared the large-scale rioting that engulfed Lahore earlier in 1947, and the city's Sikh population did not shift to India before the Radcliffe Line that demarcated the border of the newly independent states of Pakistan and India was announced.[12]

The Sikh population had not made arrangements to leave and remained trapped in the city until 31 August 1947.[12] The city's Sacha Sauda refugee camp hosted upwards of 100,000 Sikh refugees who had come to the city after fleeing nearby Gujranwala and other surrounding areas earlier that year.[12] Fierce violence erupted in the city, and an estimated 10,000 people were killed in Sheikhupura between 16 August and 31 August in communal rioting between Sikhs and Muslims.[12] Large numbers of Sikh women were killed by Sikh men in an attempt to prevent Muslim rioters from reaching them.[12]

Notable people

- Mahmood Akbar Khan Shaheed,MNA City Sheikhupura NA 102, Pakistani Politician

- Masood Akbar Khan Shaheed, Vice District Chairman Sheikhupura, Pakistani Politician

- Begum Khurshaid Mahmood Akbar Khan, Ex-MNA City Sheikhupura NA 102, Pakistani Politician

- Begum Farzana Masood Akbar Khan, Ex-Member District Council Sheikhupura, Pakistani Politician

- Sher Akbar Khan, MPA PP 142 Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf, Pakistani Politician

- Haroon Akbar Khan, Chairman Urban Union Council Jandiala Sher Khan, Pakistani Politician

- Aaqib Javed played as fast bowler for Pakistan cricket team.

- Anjum Saeed played one Olympics for Pakistan hockey team.

- Anzhelika Tahir, Miss Pakistan World 2015, a beauty queen from Pakistan.

- Asad Ullah Khan is a renowned bureaucrat who has served as Commissioner Bahawalpur and Multan Divisions[13] where he made various contributions[14]. He has also served as Secretary Irrigation[15] and Secretary Forest, Wildlife and Fisheries Department of Punjab Government[16].

- Choudhry Bilal Ahmed, politician

- Ghulam Jilani Khan is the founder of the Chand Bagh School[17] and was also responsible for introducing Nawaz Sharif into politics by making him a finance minister first[18], then Chief Minister and eventually seeing him become the Prime Minister of Pakistan[19].

- Jahangir, Fourth Mughal Emperor, ruled from 1605-1627

- Kulwant Singh Virk, author

- Mohammad Asif a right arm medium fast bowler in cricket

- Muhammad Javed Buttar, is a former justice of Supreme Court of Pakistan

- Muhammad Nawaz Bhatti, judge and lawyer

- Nawab Kapur Singh, one of the pivotal figures of the Sikh Confederacy and founder of the Singhpuria Misl.

- Rana Naved-ul-Hasan, player for the Pakistan National Cricket Team[20]

- Rana Tanveer Hussain Federal Minister

- Saeed Anwar played three Olympics for Pakistan hockey team.

- Sheikh Salim Chishti, Sufi saint of the Chishti Order during the Mughal Empire

- Waris Shah, A Great Punjabi Sufi Poet

- Zaka Ullah Bhangoo, Pakistani army aviator

- Zia Ullah Khan is attributed with major contributions in the military such as serving as Corps Commander of XII Corps Quetta[21][22].

- Zulfiqar Ahmad Dhillon, retired brigadier in the Pakistani army

- Saeed-ul haq Dogar, Pakistani Politician

- Punjab College, Sargodha Road

- Noor Ul Huda Islamic Scientific School System Harn Minar Road

- National Model School, Sargodha road

- Punjab Public School, Housing Colony

See also

- Hiran Minar, minaret built in the early 17th century

- Sheikhupura Stadium

References

- ↑ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Hiran Minar and Tank, Sheikhupura - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ↑ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Hiran Minar and Tank, Sheikhupura - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 29 April 2017.

- ↑ http://www.pbs.gov.pk/sites/default/files/%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D/tables/POPULATION%20SIZE%20AND%20GROWTH%20OF%20MAJOR%20CITIES.pdf

- ↑ Kot Dayal Das

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Sheikupura City Profile" (PDF). Urban Unit. Government of Pakistan.

- ↑ "Sheikhupura's historical sites attractive for tourists". The Nation. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ↑ District Profile: Central Punjab- Sheikhupura Archived 6 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ orientalarchitecture.com. "Asian Historical Architecture: A Photographic Survey". www.orientalarchitecture.com. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ↑ Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2011). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 9780812207286.

- 1 2 3 4 Ali, Aown (2014-09-03). "The crumbling glory of Sheikhupura Fort". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2018-01-21.

- ↑ Ahmad, Iram. "COLONIAL TRANSFORMATION IN THE DISTRICT OF SHEIKHUPURA, 1849-1947" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Menon, Ritu; Bhasin, Kamla (1998). Borders & Boundaries: Women in India's Partition. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813525525.

- ↑ 'Dasti Stages Sit-In Outside Multan Commissioner Office' (Thenews.com.pk, 2014) <https://www.thenews.com.pk/archive/print/540378> accessed 14 September 2018.

- ↑ Muhammad Omar, 'Preserving And Promoting Heritage: City Of Saints To Turn Tourist Hub' (Pakistan Defence, 2016) <https://defence.pk/pdf/threads/preserving-and-promoting-heritage-city-of-saints-to-turn-tourist-hub.397933/> accessed 14 September 2018.

- ↑ 'Ahead Of The Monsoon: Arrangements To Counter Floods Reviewed | The Express Tribune' (The Express Tribune, 2017) <https://tribune.com.pk/story/1440691/ahead-monsoon-arrangements-counter-floods-reviewed/> accessed 14 September 2018.

- ↑ 'Secretaries | Forest, Wildlife & Fisheries Department' (Fwf.punjab.gov.pk, 2018) <https://fwf.punjab.gov.pk/our_secretaries> accessed 14 September 2018.

- ↑ Footnote: 'The Founder' (Chandbagh.edu.pk) <https://www.chandbagh.edu.pk/Foundation/Index.aspx#GeneralJilani> accessed 14 September 2018.

- ↑ Aminullah Chaudry, 'The Army in Pakistan's Politics' in Hijacking from the Ground: The Bizarre Story of PK 805 (2009), p. 14

- ↑ https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/comment/the-rise-and-fall-of-nawaz-sharif/443676.html

- ↑ https://cricketarchive.com/Archive/Players/19/19517/19517.html

- ↑ 'XII Corps (Pakistan)' (En.wikipedia.org, 2018) <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/XII_Corps_(Pakistan)> accessed 14 September 2018.

- ↑ 'XII Corps' (Global Security) <https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/pakistan/xii-corps.htm> accessed 14 September 2018.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sheikhupura. |